Abstract

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is a rare disorder in which the left ventricular endocardial surface is not appropriately flattened and is heavily trabeculated. Patients with this condition can be affected by stroke from emboli that originate from these recesses. We present a patient with LVNC who was originally misdiagnosed as having an idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Ultimately, diagnosis of LVNC was confirmed through the use of 64-slice multidetector cardiac computed tomography (CT). There are few reports of using multidetector CT for diagnosis of LVNC, but this appears to be a viable option in confirming the diagnosis and at the same time assessing the coronary arteries. The recognition of this cardiomyopathy and its differentiation from other nonischemic cardiomyopathies have important implications for the patient and for family members, given its potential familial inheritance patterns and poor long-term prognosis.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old man was diagnosed with heart failure in 2008 when he was 27 years old. Coronary angiography did not show significant narrowing, and he was treated medically. He was diagnosed in 2011 with diabetes mellitus type 2 and around that time presented to a regional hospital with a large left-sided stroke and a smaller right-sided stroke, both believed to be embolic in origin. Transthoracic and then transesophageal echocardiography reconfirmed severely dilated ventricular cavities and echogenicity in the left ventricular apex, suspicious for recanalized thrombus. Transesophageal echocardiography also suggested the incidental finding of a bicuspid aortic valve.

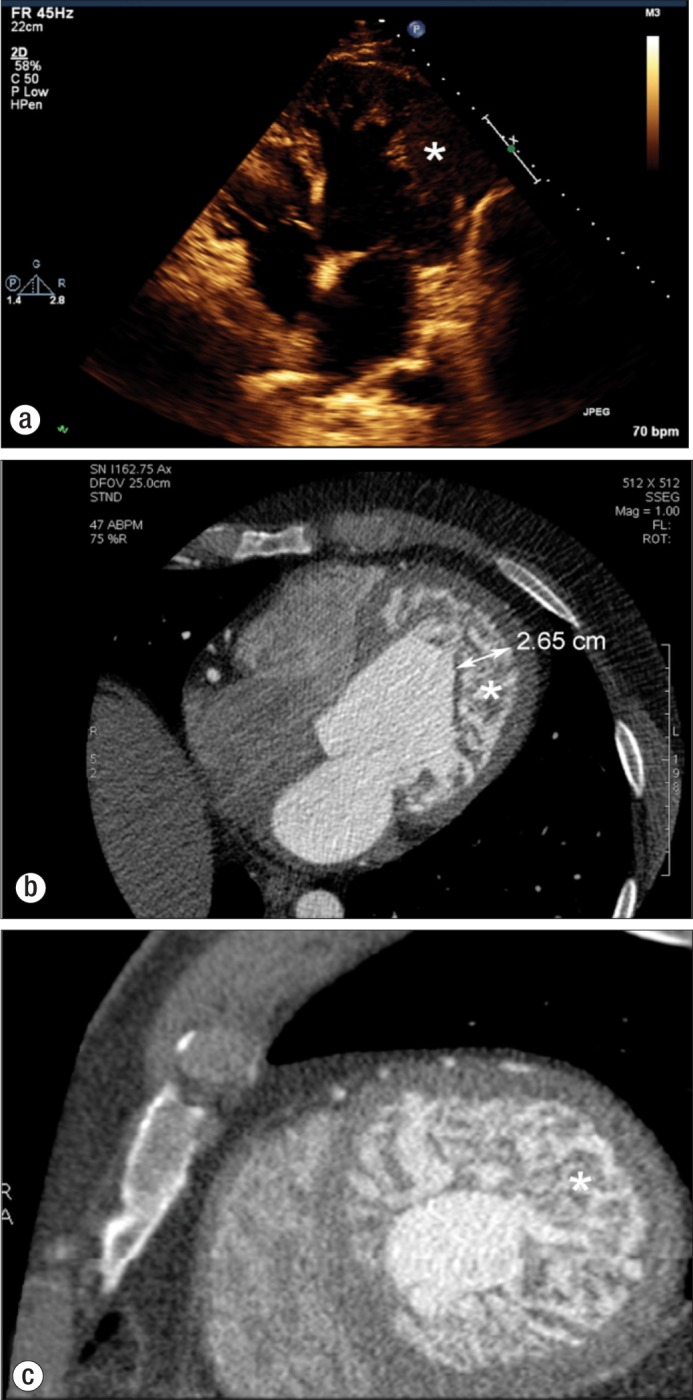

The patient was started on warfarin. He gradually improved but was left with mild dysarthria and left-sided weakness. In 2012, he sought care at Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas. Repeat echocardiogram showed excessive trabeculation of the left ventricular endocardium, consistent with a diagnosis of left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) (Figure).

Figure.

(a) Echocardiographic four-chamber view demonstrating thickened endocardium with numerous sinusoids (asterisk). Computed tomographic images in (b) an axial plane and (c) a short-axis plane clearly demonstrate a noncompacted endocardium (asterisk) that is at least twice the thickness of the compacted myocardium.

A 64-slice gated multidetector computed tomography (CT) scan of the heart (Lightspeed VCT, GE Healthcare) confirmed both the lack of coronary narrowing and the presence of excessively trabeculated endocardium, at least 2.5 times the thickness of the compacted portion of the left ventricular wall. The patient was treated medically. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was placed for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

DISCUSSION

LVNC is a morphologic abnormality of the left ventricular myocardium characterized by a failure of the left ventricular myocardium to appropriately form. It is exemplified by a ventricular wall with prominent trabeculations and deep intertrabecular recesses. This abnormality is thought to be secondary to the intrauterine arrest of myocardial compaction that occurs in the early stages of fetal development resulting in two layers of myocardium, a compacted and a noncompacted layer (1, 2). There is continuity between the ventricular cavity and the intertrabecular recesses of the trabeculated layer. A reduction in ejection fraction and decrease in the coronary flow reserve are often observed in segments with wall motion abnormalities (3).

LVNC is classified as a primary genetic cardiomyopathy by the American Heart Association (4). However, a recent comprehensive review by Oechslin and Jenni (5) concluded that the paradigm of LVNC being a specific disease entity should be revisited and that LVNC might just be a morphological expression or a phenotypic variant of other cardiomyopathies of a primary genetic disorder.

At necropsy, a variety of gross patterns of noncompaction have been noted, including coarse trabeculae resembling multiple papillary muscles and sponge-like, interlacing, smaller muscle bundles (6, 7). Histologic findings are nonspecific, and most studies have described the presence of necrosis and interstitial fibrosis in endomyocardial biopsy (8, 9).

The prevalence of adult LVNC ranges from 0.01% to 0.27% (1, 10). A review from Switzerland identified 34 cases within 15 years in a population of patients who underwent echocardiographic examination, which represented 0.014% of the echocardiograms (11). The prevalence of the disease was around 18% to 50% among members of affected families (12). In one large center, the prevalence of LVNC was reported as 3% among 960 patients with heart failure (13).

Several cardiac abnormalities may be associated with noncompaction of the myocardium, including congenital right or left ventricular outflow tract abnormalities, such as pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (14). Coronary artery abnormalities, common in right or left ventricular outflow tract abnormalities, are typically not seen in isolated LVNC (15). Other associations with LVNC have included Ebstein's anomaly, bicuspid aortic valve, aorta-to-left-ventricular tunnel, and transposition of the great vessels (16, 17).

The clinical manifestations of LVNC vary widely. Patients may be asymptomatic or have symptoms of heart failure, arrhythmias, or thromboembolism (18, 19). Electrocardiographic abnormalities include bundle branch block and arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. Association with bradycardia and Wolff Parkinson White syndrome was described in 18% of pediatric patients with LVNC (20).

The diagnosis of LVNC is often made by echocardiography, which is often the first diagnostic method used. Other nonspecific findings that can be seen on echocardiography include reduced global left ventricular systolic function, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left ventricular thrombi, and abnormal papillary muscle structure (9). The diagnostic criteria to confirm LVNC are summarized in the Table (9, 21, 22); the criteria most often used are those proposed by Jenni et al, a ratio of compacted to noncompacted myocardium >2 (9).

Table.

Echocardiographic criteria for left ventricular noncompaction

| Authors | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Chin et al (21) | Presence of x/y < 0.5, where: X = distance from the epicardial surface to the trabecular recess; Y = distance from the epicardial surface to the peak of trabeculations. These criteria are applied to trabeculations of the left ventricular apex with subxiphoid or apical four-chamber views at the end of diastole. |

| 2. Stollberger et al (22) |

|

| 3. Jenni et al (9) |

|

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) can play an important role in confirming the diagnosis, especially differentiating trabeculae from aberrant bands, false tendons, and abnormal insertion of papillary muscles. Compared with CMRI, echocardiography underestimated the ratio of noncompacted to compacted myocardium (23).

Contrast-enhanced CT is capable of showing the abnormal architecture of the left ventricular wall in noncompaction. CT also enables quantitative and qualitative assessment of global and regional ventricular function. Additionally, CT can be used to evaluate the coronary arteries to exclude anomalies or coronary artery disease, which is usually not feasible with CMRI or echocardiography (24).

The prevention of thromboembolic complications has been the subject of debate. Some authors have recommended prophylactic anticoagulation for all patients diagnosed with LVNC, regardless of ventricular function (1, 11). Other guidelines recommend anticoagulation for patients with decreased systolic function with ejection fractions <40%, a history of thromboembolism, or atrial fibrillation (12). ICD implantation is also indicated for primary prevention in patients with LVNC with a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35% and New York Heart Association class II to III heart failure. However, there have been a few reports of unsuccessful defibrillation by an ICD in LVNC (25). Patients with LVNC who have end-stage heart failure are candidates for cardiac transplantation; successful cardiac transplantation in those patients has been reported (7).

References

- 1.Ritter M, Oechslin E, Sutsch G, Attenhofer C, Schneider J, Jenni R. Isolated noncompaction of the myocardium in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(1):26–31. doi: 10.4065/72.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiford BC, Subbarao VD, Mulhern KM. Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 2004;109(24):2965–2971. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132478.60674.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenni R, Wyss CA, Oechslin EN, Kaufmann PA. Isolated ventricular noncompaction is associated with coronary microcirculatory dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(3):450–454. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01765-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, Moss AJ, Seidman CE, Young JB. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006;113(14):1807–1816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oechslin E, Jenni R. Left ventricular non-compaction revisited: a distinct phenotype with genetic heterogeneity? Eur Heart J. 2011;32(12):1446–1456. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke A, Mont E, Kutys R, Virmani R. Left ventricular noncompaction: a pathological study of 14 cases. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(4):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts WC, Karia SJ, Ko JM, Grayburn PA, George BA, Hall SA, Kuiper JJ, Meyer DM. Examination of isolated ventricular noncompaction (hypertrabeculation) as a distinct entity in adults. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(5):747–752. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finsterer J, Stollberger C, Feichtinger H. Histological appearance of left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Cardiology. 2002;98(3):162–164. doi: 10.1159/000066316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenni R, Oechslin E, Schneider J, Attenhofer Jost C, Kaufmann PA. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: a step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86(6):666–671. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stollberger C, Blazek G, Winkler-Dworak M, Finsterer J. [Sex differences in left ventricular noncompaction in patients with and without neuromuscular disorders] Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61(2):130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oechslin EN, Attenhofer Jost CH, Rojas JR, Kaufmann PA, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(2):493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy RT, Thaman R, Blanes JG, Ward D, Sevdalis E, Papra E, Kiotsekoglou A, Tome MT, Pellerin D, McKenna WJ, Elliott PM. Natural history and familial characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(2):187–192. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovacevic-Preradovic T, Jenni R, Oechslin EN, Noll G, Seifert B, Attenhofer Jost CH. Isolated left ventricular noncompaction as a cause for heart failure and heart transplantation: a single center experience. Cardiology. 2009;112(2):158–164. doi: 10.1159/000147899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauer RM, Fink HP, Petry EL, Dunn MI, Diehl AM. Angiographic demonstration of intramyocardial sinusoids in pulmonary-valve atresia with intact ventricular septum and hypoplastic right ventricle. N Engl J Med. 1964;271:68–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196407092710203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stollberger C, Finsterer J, Blazek G, Hanafin A, Winkler-Dworak M. Coronary angiography in noncompaction with and without neuromuscular disorders. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(3):667–672. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attenhofer Jost CH, Connolly HM, O'Leary PW, Warnes CA, Tajik AJ, Seward JB. Left heart lesions in patients with Ebstein anomaly. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(3):361–368. doi: 10.4065/80.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali SK. Unique features of non-compaction of the ventricular myocardium in Arab and African patients. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008;19(5):241–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conces DJ, Jr, Ryan T, Tarver RD. Noncompaction of ventricular myocardium: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(4):717–718. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.4.2003432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hook S, Ratliff NB, Rosenkranz E, Sterba R. Isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 1996;17(1):43–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02505811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichida F, Tsubata S, Bowles KR, Haneda N, Uese K, Miyawaki T, Dreyer WJ, Messina J, Li H, Bowles NE, Towbin JA. Novel gene mutations in patients with left ventricular noncompaction or Barth syndrome. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1256–1263. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, Jue K, Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990;82(2):507–513. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stollberger C, Finsterer J, Blazek G. Left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction and association with additional cardiac abnormalities and neuromuscular disorders. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(8):899–902. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuny F, Jacquier A, Jop B, Giorgi R, Gaubert JY, Bartoli JM, Moulin G, Habib G. Assessment of left ventricular non-compaction in adults: side-by-side comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with echocardiography. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103(3):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazel P, Peterman MA, Schussler JM. Three-year outcomes and cost analysis in patients receiving 64-slice computed tomographic coronary angiography for chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(4):498–500. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastore G, Zanon F, Baracca E, Piva M, Bernardi A, Piergentili C, Rigatelli G, Roncon L, Barold SS. Failure of transvenous ICD to terminate ventricular fibrillation in a patient with left ventricular noncompaction and polycystic kidneys. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35(2):e40–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]