Abstract

Background

Research on the structure of comorbidity among common mental disorders has largely focused on current prevalence rather than on the development of comorbidity. This report presents preliminary results of the latter type of analysis based on the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A).

Methods

A national survey was carried out of adolescent mental disorders. DSM-IV diagnoses were based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview administered to adolescents and questionnaires self-administered to parents. Factor analysis examined comorbidity among 15 lifetime DSM-IV disorders. Discrete-time survival analysis was used to predict first onset of each disorder from information about prior history of the other 14 disorders.

Results

Factor analysis found four factors representing fear, distress, behavior, and substance disorders. Associations of temporally primary disorders with the subsequent onset of other disorders (dated using retrospective age-of-onset reports) were almost entirely positive. Within-class associations (e.g., distress disorders predicting subsequent onset of other distress disorders) were more consistently significant (63.2%) than between-class associations (33.0%). Strength of associations decreased as comorbidity among disorders increased. The percent of lifetime disorders explained (in a predictive rather than causal sense) by temporally prior disorders was in the range 3.7-6.9% for earliest-onset disorders (specific phobia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) and much higher (23.1-64.3%) for later-onset disorders. Fear disorders were the strongest predictors of most other subsequent disorders.

Conclusions

Adolescent mental disorders are highly comorbid. The strong associations of temporally primary fear disorders with many other later-onset disorders suggest that fear disorders might be promising targets for early interventions.

Keywords: NCS-A, adolescence, epidemiology, lifetime prevalence, lifetime comorbidity, mental disorders

Epidemiological surveys of child-adolescent mental disorders consistently find high comorbidity (Angold et al., 1999; Fergusson et al., 1994; Newman et al., 1996). A number of longitudinal studies have examined temporal progression among these comorbid disorders (Pine et al., 1998; Reinke & Ostrander, 2008; Stein et al., 2001). However, these studies have generally (Costello et al., 1996; Fergusson et al., 1993; McGee et al., 1992), although not always (Lieb et al., 2000; Shankman et al., 2009), focused on point prevalence in each wave or the cumulation of point prevalence estimates across multiple waves (Costello et al., 2003; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). For example, the Great Smoky Mountain Study assessed 3-month mental disorders once yearly in three cohorts of children (Costello et al., 2003). This approach makes it impossible to distinguish associations of primary disorders with onset versus persistence of secondary disorders. Such a distinction, which would require examining temporal sequencing across lifetime rather than recent disorders, could have value in interpreting longitudinal associations and strategizing about intervention possibilities (Angold et al., 1999). There are exceptions, though. For example, the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study (Wittchen et al., 1998) is a large-scale longitudinal study that examined temporal sequencing of lifetime disorders in a cohort of adolescents followed into adulthood. Among the important findings this design allowed are that temporally prior GAD predicts the subsequent onset of other anxiety disorders more strongly than the subsequent onset of depression (Beesdo et al., 2010) and that social phobia is associated with subsequent onset of temporally secondary depression (Beesdo et al., 2007). However, this kind of analysis has never been used to examine temporal sequencing of disorder onsets across the full range of commonly occurring mental disorders.

The current report presents results of a preliminary analysis of the associations between temporally prior lifetime disorders and the subsequent first onset of temporally secondary disorders based on the data collected in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), a national survey of adolescent DSM-IV disorders (Merikangas et al., 2009). The results are only preliminary because the data are cross-sectional and temporal associations are inferred from retrospective age-of-onset (AOO) reports. Nonetheless, intriguing results emerge that could be useful in generating hypotheses to be examined in subsequent longitudinal studies. Previous studies would lead us to expect stronger inter-temporal associations within than between anxiety-mood and behavioral disorders (Copeland et al., 2009; Reinke & Ostrander, 2008) and strong associations of temporally primary behavior disorders with later substance disorders (Copeland et al., 2009; Elkins et al., 2007; Tapert et al., 2002), but we had no initial hypotheses about other specifications.

METHODS

Sample

Adolescents (ages 13-17) were interviewed between February 2001 and January 2004 in dual-frame household and school samples described elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2009a; Kessler et al., 2009b). The household sample included 904 adolescents (879 in school, 25 dropouts) from households in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) (Kessler & Merikangas, 2004). The school sample included 9,244 adolescents from a representative sample of schools in the adult sample areas of that survey. The conditional adolescent response rate was 86.8-82.6% (household and school samples, respectively). The household sample includes school dropouts and adolescents residing in areas where schools refused to participate. A high (72.0%) percent of initially-selected schools refused to participate and were replaced with matched replacement schools. Comparison of household sample respondents from nonparticipating schools with school sample respondents from replacement schools found no evidence of bias in estimates of either disorder prevalence or correlates (Kessler et al., 2009a).

One parent or surrogate (henceforth referred to as parents) of participating adolescents was asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire about the adolescent’s developmental history and mental health. The conditional response rate was 82.5-83.7% (household and school samples, respectively). This report focuses on the 6,483 adolescent-parent pairs where complete data are available from both adolescents and parents. The fact that parent data were available for only a subset of adolescent respondents was taken into consideration by weighting the data in complete parent-adolescent pairs to adjust for differences with incomplete pairs. These weighting procedures are discussed in detail elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2009a; Kessler et al., 2009b).

Written parent informed consent and adolescent assent were obtained before surveying either the parent or adolescent. Each respondent was given $50 for participation. These recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of both Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. Once the survey was completed, cases were weighted for within-household probability of selection (household sample) and deviation from Census population socio-demographic/geographic distributions, making each sample nationally representative on the socio-demographic/geographic variables. The samples were then merged with sums of weights proportional to relative sample sizes adjusted for design effects in estimating disorder prevalence. These procedures are detailed elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2009a; Kessler et al., 2009b).

Diagnostic assessment

Adolescents were administered the fully-structured Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) modified to simplify language and use examples relevant to adolescents (Merikangas et al., 2009). The 15 DSM-IV disorders assessed include mood disorders (major depressive disorder/dysthymia, bipolar I-II disorder and sub-threshold bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder), behavior disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, eating disorders [anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating behavior]), and substance disorders (alcohol and drug abuse, alcohol and drug dependence with abuse). There were no other exclusionary diagnoses. These disorders include all those assessed in most previous adolescent epidemiological studies.

Adolescent interviews assessed all disorders. Parent questionnaires assessed only disorders for which parent reports have previously been found important in diagnosis: behavior disorders (Johnston & Murray, 2003) and depression/dysthymia (Braaten et al., 2001). Parent and adolescent reports were combined at the symptom level using an “or” rule (except in the case of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, where only parent reports were used based on evidence of invalidity of adolescent reports). All diagnoses were made using DSM-IV distress/impairment criteria and organic exclusion rules, but diagnostic hierarchy rules were not used because we wanted to study comorbidity among hierarchy-free disorders.

A clinical reappraisal study interviewed adolescent-parent pairs by telephone with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) Lifetime Version (Kaufman et al., 1997). As detailed elsewhere, concordance was good between survey and clinical diagnoses (Kessler et al., 2009c), with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of .81-.94 for fear disorders, .79-.86 for distress disorders, .78-.98 for behavior disorders, and .92-.98 for substance disorders. Parent and adolescent reports both contributed to AUC when both were assessed for depression/dysthymia (.75, .71, and .87 for adolescent, parent, and combined reports, respectively), oppositional-defiant disorder (.71, .66, and .85), and conduct disorder (.59, .96, and .98), but only parent reports contributed to AUC for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (.57, .71, and .78). Adolescent disorder AOO reports were obtained retrospectively using probes shown experimentally to maximize recall accuracy among adults (Knauper et al., 1999).

Analysis Methods

AOO curves were generated using the actuarial method (Halli et al., 1992). Tetrachoric factor analysis (principal axis method) with promax rotation was used to examine bivariate comorbidity. Temporal unfolding was studied by examining predictive associations between temporally primary disorders (based on retrospective AOO reports) and first onset of later disorders with multivariate discrete-time survival models using a person-year dataset (Willett & Singer, 1993). The details of this modeling procedure, which we have used extensively in previous NCS reports, are presented elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2005). Each model predicted first onset of one disorder from information about prior lifetime occurrence of the other 14 disorders controlling basic socio-demographic variables (sex, race/ethnicity [Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other], region of the country [Northeast, Midwest, South, West], urbanicity [Major Metropolitan Area, other urbanized area, rural area], parent education [less than high school, high school, some college, college graduate, coded for the parent with the higher level of education], number of biological parents with whom the adolescent lives [0-2], birth order [only child, oldest, youngest, other], number of siblings, and age).

Several more complex models allowed non-additive associations to exist among the predictor disorders. One of these added to the additive multivariate model a series of dummy variables for number of prior lifetime disorders beginning with two. These dummy variables represent gross interaction terms that require the coefficient to be the same for all combinations of disorders of a given number (e.g., all pairs of disorders, all sets of three disorders). A somewhat more complex model weighted the disorders in each of these sets to have differential slopes proportional to the main effects of the disorders. Another specification allowed for interactions between a continuous measure of number of prior lifetime disorders and each type of prior lifetime disorders. More detailed information about these models are presented in a previous report in this journal (Alonso et al., 2011). The best-fitting model among these alternatives was selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). Survival coefficients and standard errors were exponentiated to produce odds-ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals.

Population attributable risk proportions (PARPs) were calculated to describe strength of association between predictor disorders and outcome disorders. PARPs are the proportions of outcome disorders that would not have occurred in the absence of predictor disorders under the model if the survival coefficients represent causal effects. The proportions were calculated by generating a conditional predicted probability of first onset of each outcome disorder at each year of life of each respondent from the coefficients in the best-fitting survival model twice: once using all model coefficients and then again omitting coefficients for the predictor disorders. The actuarial method (Halli et al., 1992) was used to cumulate conditional predicted probabilities to respondent age at interview. PARP was defined as 1-R, where R represents the ratio of mean cumulative predicted probability in the second specification divided by mean cumulative predicted probability in the first specification.

As the survey data are both clustered and weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization method implemented in the SUDAAN software system (Research Triangle Institute, 2002) was used to estimate standard errors of prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals of ORs. Significance of predictor sets was evaluated using Wald χ2 tests based on design-based variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated using .05-level two-sided tests.

RESULTS

Lifetime prevalence and comorbidity

A previous NCS-A report documented high lifetime prevalence of disorders (Merikangas et al., 2010). Overall prevalence is even higher in the current data because we included sub-threshold bipolar disorder, which was omitted from the earlier report. (Table 1) Comorbidity is also more common because we analyze hierarchy-free diagnoses, with 27.9% of respondents meeting criteria for two or more disorders and a mean of 3.5 disorders among those with comorbidity. All but two of the 105 tetrachoric correlations among disorder pairs (15×14/2) are positive (82.5% statistically significant), with a median of .29 and inter-quartile range (25th-75th percentiles) of .20-.37. (The tetrachoric correlation matrix is available on request.)

Table 1. Lifetime prevalence of estimated DSM-IV disorders along with standard errors of prevalence estimates (se) and rotated (promax) factor pattern of comorbid disorders in the sub-sample with complete parent data (n=6,483)a.

| Prevalenceb | Rotated Factor Pattern (Standardized Regression Coefficients) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | se | I. Fear disorders |

II. Distress disorders |

III. Behavior disorders |

IV. Substance Disorders |

|

|

|

||||||

| I. Fear disorders | ||||||

| Specific phobia | 19.9 | 1.0 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.10 |

| Agoraphobiac | 2.6 | 0.4 | 0.79 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.00 |

| Social phobia | 8.5 | 0.6 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Panic disorderd | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.68 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.15 |

| Any fear disorder | 26.1 | 1.0 | ||||

| II. Distress disorders | ||||||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 7.6 | 0.5 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.11 | −0.27 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4.7 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.13 |

| Major depressive episode/dysthymia | 18.6 | 1.1 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.17 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.07 | 0.87 | −0.08 | 0.01 |

| Any distress disorder | 25.4 | 0.9 | ||||

| III. Behavior disorders | ||||||

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 8.1 | 0.6 | −0.15 | −0.13 | 0.94 | −0.07 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 12.6 | 0.9 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.25 |

| Conduct disorder | 6.8 | 0.9 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.44 |

| Eating disorderse | 5.1 | 0.4 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.54 | −0.14 |

| Any behavior disorder | 22.7 | 1.3 | ||||

| IV. Substance disorders | ||||||

| Alcohol abusef | 6.1 | 0.5 | −0.18 | 0.23 | −0.11 | 0.89 |

| Drug abusef | 8.9 | 0.8 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.91 |

| Any substance disorder | 11.4 | 0.9 | ||||

| V. Other disorders | ||||||

| Bipolar disorderg | 6.2 | 0.4 | 0.38 | −0.23 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| VI. Total number of disorders | ||||||

| Any disorder | 51.3 | 1.3 | ||||

| Exactly one disorder | 23.4 | 0.9 | ||||

| Exactly two disorders | 12.0 | 0.6 | ||||

| Three or more disorders | 15.9 | 1.0 | ||||

Eigenvalues of unrotated factors: 5.2, 2.2, 1.1, 1.0, 0.9. Correlations among factors in promax rotated four-factor solution: I-II .44; I-III .25, I-IV .16, II-III .31, II-IV .29, III-IV .43.

The prevalence estimates reported here are higher than those in an earlier NCS-A report (Merikangas et al., 2010) because disorders were defined here without diagnostic hierarchy rules and included sub-threshold bipolar disorder. Estimated comorbidity is higher than in the earlier report because of not using hierarchy rules.

Agoraphobia is assessed with or without panic disorder

Panic disorder is assessed with or without agoraphobia

Includes anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder

With or without dependence

Includes Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and sub-threshold bipolar disorder

Factor analysis finds four factors with unrotated eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Oblique (promax) rotation shows that the first factor is similar to what previous studies referred to as a fear factor (Krueger, 1999; Watson, 2005), with high loadings for panic and phobias (.67-.79).(Table 1) The second factor represents what previous studies referred to as a distress factor, including depression, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and separation anxiety disorders (.51-.87). The third factor represents behavior disorders (.49-.94) and the fourth represents alcohol-drug disorders (.89-.91), although conduct disorder (.44) and bipolar disorder (.40) also have elevated loadings. Disorders in the fear factor are the most common (26.1%), followed by distress (25.4%), behavior (22.7%), and substance (11.4%) disorders. The factors are all significantly correlated with each other, from a high Pearson correlation of .44 between fear and distress disorders to a low correlation of .16 between fear and substance disorders.

Age-of-onset distributions

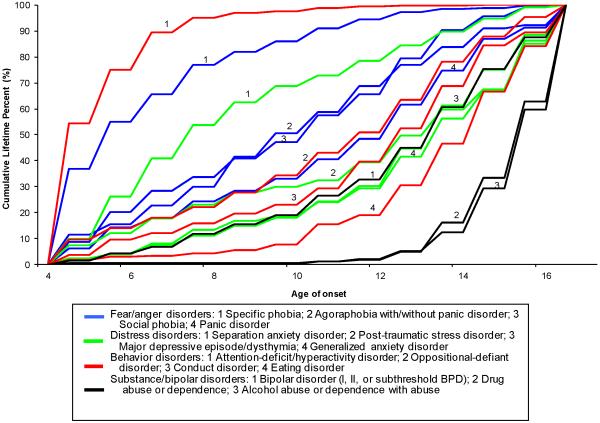

Retrospectively reported median (and inter-quartile range) AOO of any disorder is 8 (6-13) years old. A clear temporal order exists across disorders within classes. (Figure 1) Specific phobia has the earliest AOO (Median) within fear disorders (6), separation anxiety disorder within distress disorders (8), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder within behavior disorders (6). The next earliest AOO distributions are for other fear (11-12) and behavior (12-13) disorders. Bipolar disorder (14), the remaining distress disorders (14), eating disorders (15), and substance disorders (16) have the latest median AOO.

Figure 1.

Age-of-onset (AOO) distributions based on retrospective age-of-onset reports among respondents with lifetime DSM-IV/Composite International Diagnostic Interview disorders

Bivariate associations between earlier and later disorders

We estimated 210 (14×15) bivariate survival models, each with one lifetime disorder as a time-varying predictor of subsequent first onset of one other disorder, controlling socio-demographics. 89.3% of coefficients were positive and 59.5% significant. (Detailed results are available on request.) The median (inter-quartile range) ORs of significant positive survival coefficients were 3.1 (2.3-3.9). Only two coefficients were negative and significant, both involving associations of substance disorders with later agoraphobia.

The best-fitting model

The best-fitting multivariate model pooled across all outcomes was one that predicted first onset of each disorder from dummy variables for prior disorders plus summary measures of number of prior disorders. (Detailed results of model-fitting are available on request.) The number-of-disorders measures include dummy variables for exactly two to seven+ disorders.

Coefficients associated with pure disorders

The disorder type coefficients in the best-fitting model represent predictive associations of disorders that occur to people with no prior disorders. As there are a large number of coefficients for these pure disorders, it is useful to focus on summary statistics. (Detailed results are available on request.) 40.0% of pure-disorder coefficients are positive and statistically significant. (Table 2) Median (inter-quartile range) ORs are 3.1 (2.4-3.9). Only one of 210 coefficients is negative and significant. Roughly two-thirds (63.2%) of within-class coefficients are significant versus 33.0% of between-class coefficients. The median (inter-quartile range) significant within-class ORs [3.9 (3.0-4.8)] are higher than comparable between-class ORs [2.9 (2.4-3.5)].

Table 2. Predictive associations (percent significant and range of significant odds-ratios) of temporally primary pure lifetime estimated DSM-IV disorder types with the subsequent first onset of other estimated DSM-IV disorders based on the best-fitting multivariate survival model (n = 6,483)a.

| Predictor disorders | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Outcome disorders | Fear disorders |

Distress disorders |

Behavior Disorders |

Substance disorders |

Bipolar disorder |

All disorders |

||||||

| %g | ORsh | %g | ORsh | %g | ORsh | %g | ORsh | %g | ORsh | %g | ORsh | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| I. Fear disorders | ||||||||||||

| Specific phobia | 33.3 | 3.9 | 50.0 | 1.8-3.2 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 21.4 | 1.8-3.9 |

| Agoraphobiab | 66.7 | 4.8-9.2 | 50.0 | 2.8-3.3 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 28.6 | 2.8-9.2 |

| Social phobia | 66.7 | 3.6-4.2 | 50.0 | 1.8-2.1 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 30.8 | 1.8-4.2 |

| Panic disorderc | 33.3 | 3.3 | 25.0 | 3.1 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 14.3 | 3.1-3.3 |

| II. Distress disorders | ||||||||||||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 50.0 | 2.4-2.7 | 66.7 | 2.4-4.7 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 28.6 | 2.4-4.7 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 50.0 | 3.0-3.9 | 66.7 | 3.7-4.7 | 0 | - | 50.0 | 4.7 | 100.0 | 3.2 | 42.9 | 3.0-4.7 |

| Major depressive episode/dysthymia | 100.0 | 1.7-3.3 | 33.3 | 3.4 | 100.0 | 2.3-3.4 | 50.0 | 4.4 | 0 | - | 71.4 | 1.7-4.4 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 50.0 | 2.8-3.1 | 100.0 | 2.5-5.1 | 0 | - | 50.0 | 4.3 | 0 | - | 42.9 | 2.5-5.1 |

| III. Behavior disorders | ||||||||||||

| ADHD | 0 | - | 0 | - | 66.7 | 3.7-5.6 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 20.0 | 3.7-5.6 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 75.0 | 1.9-2.9 | 50.0 | 2.0-3.6 | 66.7 | 2.3-4.9 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 50.0 | 1.9-4.9 |

| Conduct disorder | 50.0 | 1.8-3.4 | 25.0 | 4.4 | 66.7 | 2.3-3.0 | 50.0 | 10.3 | 0 | - | 42.9 | 1.8-10.3 |

| Eating disordersd | 50.0 | 2.4-3.7 | 50.0 | 2.5-3.8 | 66.7 | 2.2-4.1 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 42.9 | 2.2-4.1 |

| IV. Substance disorders | ||||||||||||

| Alcohol abusee | 25.0 | 2.6 | 25.0 | 3.1 | 50.0 | 2.8-3.5 | 100.0 | 8.3 | 0 | - | 35.7 | 2.6-8.3 |

| Drug abusee | 50.0 | 2.4 | 25.0 | 2.1 | 75.0 | 2.8-6.1 | 100.0 | 8.4 | 100.0 | 3.2 | 57.1 | 2.1-8.4 |

| V. Other disorders | ||||||||||||

| Bipolar disorderf | 75.0 | 2.8-4.3 | 50.0 | 1.8-5.7 | 100.0 | 2.3-4.4 | 0 | 0 | 64.3 | 1.8-5.7 | ||

Based on a discrete-time (person-year) survival model in which first lifetime onset of each of the 15 estimated DSM-IV disorders is predicted by 14 dummy variables for prior lifetime history of the other disorders, dummy variables for number of prior lifetime disorders (2-7+), and socio-demographic controls (sex, race/ethnicity, region of the country, urbanicity, parent education, number of biological parents with whom the adolescent lives, birth order, number of siblings, and age).

Agoraphobia is assessed with or without panic disorder

Panic Disorder is assessed with or without agoraphobia

Includes anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder

With or without dependence

Includes Bipolar-I, Bipolar-II, and sub-threshold bipolar disorder

Percent of coefficients that are significant at the .05 level using two-sides design-based significance tests

Range of significant ORs

The same general pattern holds within each class of disorders. 50.0-100% of within-class ORs are significant vs. 15.9-64.3% of between-class coefficients. The percentage of significant between-class coefficients is much lower predicting fear (15.9%) than other (29.6-64.3%) disorders. One or two disorders are the most powerful within-class predictors in each class: specific phobia and social phobia among the fear disorders; major depression for distress disorders; and attention-deficit/hyperactivity and conduct disorders for behavior disorders. Fear disorders have the highest proportion of significant between-class coefficients predicting other disorders (52.3%) followed by distress (36.4%), behavior (29.6%), and substance (15.4%) disorders. Two of the three most consistent predictors are fear disorders: social phobia (81.8%) and specific phobia (72.7%), the other being major depression (72.7%).

Coefficients associated with comorbidity

The coefficients associated with number of predictor disorders in the best-fitting model represent predictive associations of comorbidity expressed as deviations from the pure-disorder coefficients. For example, absent effects of comorbidity, respondents with three predictor disorders having pure-disorder ORs of, say, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.7 would have an expected OR of 3.3 (i.e., 1.3 × 1.5 × 1.7). If the actual OR for these respondents is 4.0, then the number-of-disorders OR would be 1.2 (i.e., 4.0/3.3), indicating that the predictive effect of comorbidity is 20% higher than expected from the pure-disorder coefficients. The best-fitting model assumes that these number-of-disorders coefficients are a function of each respondent’s weighted number of predictor disorders, with weights defined by pure-disorder coefficients.

With this interpretation in mind, 87.2% of the number-of-disorder coefficients in the best-fitting model are less than 1.0 across equations, indicating a general pattern of sub-additive interaction in the logistic specification; that is, a pattern in which the joint effects of the interacting predictors are significantly less than those estimated in a model that assumes that no interactions exist. (Table 3) One-third of these sub-additive coefficients are statistically significant, while none of the ORs greater than 1.0 is significant. This pattern of the predictive associations of comorbidity generally being less than the product of their parts becomes stronger as the number of disorders in the comorbid profile increases from a median OR of 0.8 for two disorders to 0.1 for 7+ disorders.

Table 3. Predictive associations (odds-ratios) along with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of number of lifetime estimated DSM-IV disorders with the subsequent first onset of other estimated DSM-IV disorders based on the best-fitting multivariate survival model (n = 6,483)a.

| Number of predictor disorders | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7+ | |||||||

| Outcome disorders | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) |

|

|

||||||||||||

| I. Fear disorders | ||||||||||||

| Specific phobia | 1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | 0.3 | 0.1-1.1 | 0.9 | 0.2-4.9 | 0.7 | 0.1-7.0 | 1.2 | 0.1-11.4 | 3.6 | 0.3-45.5 |

| Agoraphobiab | 0.6 | 0.2-1.7 | 0.4 | 0.0-2.4 | 0.4 | 0.0-3.8 | 0.1 | 0.0-2.0 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0-6.4 |

| Social phobia | 0.8 | 0.4-1.9 | 0.6 | 0.2-2.0 | 0.4 | 0.1-2.7 | 0.1 | 0.0-1.5 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.7 | 1.0 | 0.0-65.5 |

| Panic disorderc | 0.9 | 0.4-2.2 | 1.1 | 0.2-6.7 | 0.4 | 0.0-7.6 | 0.3 | 0.0-6.4 | 0.4 | 0.0-14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0-5.1 |

| II. Distress disorders | ||||||||||||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 0.7 | 0.3-1.6 | 1.0 | 0.3-3.2 | 0.9 | 0.2-4.7 | 0.7 | 0.1-5.4 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.2 | 1.8 | 0.1-51.6 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 0.7 | 0.3-1.6 | 0.6 | 0.1-2.3 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.3 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0-1.7 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.4 |

| Major depressive disorder/dysthymia | 0.8 | 0.4-1.3 | 0.4* | 0.2-0.8 | 0.2* | 0.1-0.6 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.2 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.4 | - | - |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1.0 | 0-.33.6 | 0.9 | 0.1-5.5 | 0.7 | 0.1-9.0 | 0.2 | 0.0-3.5 | 0.2 | 0.0-8.8 | 0.0 | 0.0-28.6 |

| III. Behavior disorders | ||||||||||||

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1.2 | 0.3-5.1 | 3.0 | 0.3-30.2 | 0.6 | 0.0-15.3 | ||||||

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 0.8 | 0.4-1.6 | 0.6 | 0.3-1.2 | 0.2* | 0.0-0.9 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.8 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.4 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.5 |

| Conduct disorder | 1.0 | 0.5-2.4 | 0.4 | 0.1-1.2 | 0.4 | 0.6-2.0 | 0.2 | 0.0-1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0-1.0 | 0.2 | 0.0-9.6 |

| Eating disordersd | 0.8 | 0.3-2.1 | 0.3* | 0.1-0.8 | 0.2 | 0.0-1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0-1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0-1.3 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.04 |

| IV. Substance disorders | ||||||||||||

| Alcohol abusee | 0.6 | 0.2-1.8 | 0.6 | 0.1-2.8 | 0.3 | 0.0-2.2 | 0.1* | 0.0-0.9 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0-1.6 |

| Drug abusee | 0.9 | 0.4-1.9 | 0.4 | 0.2-1.3 | 0.2* | 0.0-1.0 | 0.1* | 0.0-1.0 | 0.3 | 0.0-4.6 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.4 |

| V. Other disorders | ||||||||||||

| Bipolar disorderf | 0.4* | 0.2-0.8 | 0.2* | 0.1-0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0-0.7 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.3 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.02 | 0.0* | 0.0-0.02 |

Significant at the .05-level, two-sided test

Based on a discrete-time (person-year) survival model in which first lifetime onset of each of the 15 estimated DSM-IV disorders is predicted by 14 dummy variables for prior lifetime history of the other disorders, dummy variables for number of prior lifetime disorders (2-7+), and socio-demographic controls (sex, race/ethnicity, region of the country, urbanicity, parent education, number of biological parents with whom the adolescent lives, birth order, number of siblings, and age).

Agoraphobia is assessed with or without panic disorder

Panic Disorder is assessed with or without agoraphobia

Includes anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder

With or without dependence

includes Bipolar-I, Bipolar-II, and sub-threshold bipolar disorder

Population attributable risk proportions

PARPs vary widely across outcomes (inter-quartile range: 35.6-54.5%). (Table 4) The lowest PARPs in terms of the outcomes are associated with specific phobia (3.7%) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (6.9%), the two earliest-onset disorders. This reflects the low prevalence and generally insignificant association of prior disorders predicting these two disorders. A similar interpretation applies to separation anxiety disorder (SAD), the outcome disorder with the next lowest risk proportion (23.1%). SAD has a comparatively early AOO distribution and is predicted by a lower than average proportion of prior disorders. The other 12 disorders, when considered as outcomes, all have risk proportions of 35.0% or higher. Those with the highest risk proportions have comparatively late AOO distributions and are either significantly predicted by the majority of other disorders (alcohol abuse, bipolar disorder), very strongly predicted by a smaller number of other disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia), or are less strongly predicted by highly prevalent disorders (generalized anxiety disorder).

Table 4. Population attributable risk proportions (PARPs) of temporally primary lifetime estimated DSM-IV disorder types predicting subsequent first onset of other estimated DSM-IV disorders based on the best-fitting multivariate survival model (n = 6,483)a.

| Types of predictor disorders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Outcome Disorder | Fear disorders |

Distress Disorders |

Behavior disorders |

Substance disorders |

Bipolar disorder |

All disorders |

|

|

||||||

| 1. Fear disorders | ||||||

| Specific phobia | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.7 |

| Agoraphobiab | 63.3 | 23.2 | − 18.8 | −0.0 | 1.0 | 62.2 |

| Social phobia | 29.0 | 5.9 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 35.6 |

| Panic Disorderc | 28.2 | 15.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 41.5 |

| II. Distress disorders | ||||||

| Separation Anxiety disorder | 19.4 | 7.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 23.1 |

| Post-traumatic Stress disorder | 38.2 | 27.0 | 11.4 | 3.8 | 8.1 | 54.5 |

| Major depression/dysthymia | 20.5 | 4.6 | 18.7 | 0.2 | −0.0 | 37.9 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 43.0 | 40.6 | 7.4 | 2.8 | −4.8 | 64.3 |

| III. Behavior disorders | ||||||

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 3.0 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 6.9 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 12.0 | 13.3 | 19.0 | −0.2 | 2.3 | 36.4 |

| Conduct disorder | 16.0 | 12.3 | 17.4 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 40.4 |

| Eating disordersd | 28.4 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 43.6 |

| IV. Substance disorders | ||||||

| Alcohol abusee | 11.4 | 11.2 | 27.4 | 11.1 | 3.8 | 48.8 |

| Drug abusee | 15.7 | 9.6 | 29.5 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 42.7 |

| V. Other | ||||||

| Bipolar disorderf | 32.2 | 25.1 | 19.0 | 0.0 | -- | 57.2 |

Based on a discrete-time (person-year) survival model in which first lifetime onset of each of the 15 DSM-IV/CIDI disorders is predicted by 14 dummy variables for prior lifetime history of the other disorders, dummy variables for number of prior lifetime disorders (2-7+), and socio-demographic controls (sex, race/ethnicity, region of the country, urbanicity, parent education, number of biological parents with whom the adolescent lives, birth order, number of siblings, and age).

Agoraphobia is assessed with or without panic disorder

Panic Disorder is assessed with or without agoraphobia

Includes anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder

With or without dependence

Includes Bipolar-I, Bipolar-II and sub-threshold bipolar disorder.

Focusing on predictor disorders, the fear disorders have the highest PARPs in predicting nearly three-fourths of all outcome disorders, including other fear disorders, all four distress disorders, eating disorder, and bipolar disorder. There are only five exceptions: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, where, as noted above, the risk proportion is very low overall; oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, where the highest risk proportions are associated with other behavior disorders; and substance disorders, where the highest risk proportions are associated with behavior disorders. As predictors, substance disorders consistently have the lowest risk proportions. Distress disorders generally have higher proportions than behavior disorders in predicting fear and distress disorders, but lower in predicting behavior and substance disorders.

DISCUSSION

It is important to recognize that the analyses reported here focused on predictors of first onset of comorbid conditions. The investigation of persistence is a separate matter that requires additional analysis not undertaken here. Furthermore, with regard to onset the analysis examined only aggregate associations and did not consider the possibility of variation in the structure or predictors of comorbidity in childhood versus adolescence, among boys versus girls, or by other potentially important sub-grouping distinctions.

Three sample limitations are noteworthy: that the school-level response rate was quite low, the individual-level response rate relatively low, and the sample excluded adolescents not enrolled in school. Methodological analysis reported elsewhere reduces concern about the first limitation, as no evidence of bias was found due to school replacement (Kessler et al., 2009a). The finding in previous methodological studies that non-respondents have higher rates of mental illness than respondents implies that the second limitation probably led prevalence estimates to be conservative, although estimates of predictive associations might be biased either upward or downward and differentially across predictor disorders (Kessler et al., 1995). The third limitation reduces the external validity of findings.

Two limitations concerning measurement are also noteworthy: that diagnoses were based on lay interviews and questionnaires rather than clinical assessments and that lifetime diagnoses and AOO reports were based on retrospective recall rather than prospective data. Concern about the first limitations is somewhat reduced by the good concordance with clinical diagnoses (Kessler et al., 2009c). The second limitation presumably reduced lifetime prevalence estimates (Moffitt et al., 2010; Patten, 2009), distorted AOO reports (Simon & von Korff, 1995), and could have biased estimates of predictive associations differentially across disorders depending on between-disorder differences in failure to recall lifetime occurrence and/or AOO. It would be very valuable to correct these limitations by replicating the complex analyses carried out here with long-term longitudinal data.

As a number of prospective studies of child-adolescent mental disorders exist (Costello et al., 2003; Newman et al., 1996; Pine et al., 1998; Reinke & Ostrander, 2008), a question can be raised why retrospective analysis of the sort reported here has value. The answer is that most existing prospective studies, with a small number of notable exceptions (Wittchen et al., 1998; Olino et al., 2010), did not obtain data on lifetime prevalence of mental disorders, making it impossible to carry out analyses of the associations between prior lifetime disorders and subsequent first lifetime onset of secondary disorders in the majority of such studies. Replication of the kinds of analyses reported here should be encouraged in the prospective studies that would support them. The results of the current analyses should be useful in providing preliminary hypotheses to be investigated in these prospective studies. This has traditionally been a major value of retrospective studies (Mantel & Haenszel, 1988).

In the context of these limitations, the differential AOO patterns found here are consistent with considerable previous evidence that attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder have the earliest ages-of-onset and that generalized anxiety, depressive, and substance disorders have the latest ages-of-onset of the adolescent disorders considered here (Kessler et al., 2007). Very similar patterns were found in parallel analyses we previously carried out in a cross-national sample of adults (Kessler et al., 2011). The high comorbidity found among disorders is also consistent with previous evidence (Angold et al., 1999).

The four-factor structure found in the NCS-A is also generally similar to findings from previous studies (Kessler et al., 2009b; Krueger, 1999; Vollebergh et al., 2001; Watson, 2005). Although a number of different specifications of the factor analysis model (e.g., at the person-level vs. person-year level, with and without sub-threshold bipolar disorder, with and without corrections for differential validity of diagnoses) yielded very similar results, replication in independent datasets is needed before considering this pattern stable.

One exception to the consistency of NCS-A results with previous factor analyses is that separation anxiety disorder (SAD) loaded with distress disorders in the NCS-A but with fear disorders some previous studies (Lahey et al., 2004). It is unclear why this occurred, but it is noteworthy that the loading of SAD on the distress factor was the weakest among all distress disorders and that SAD had the largest cross-loading with the fear factor of any distress disorder.

Another discrepancy with previous factor analysis studies is that substance disorders loaded separately from behavior disorders in the NCS-A. Substance and behavior disorders have generally loaded together in previous studies. However, this might reflect the fact that most previous factor analysis studies did not include as many behavior disorders as the NCS-A. The fact that substance and behavior disorders loaded separately in the NCS-A suggests that they have unique underlying psychopathological processes in adolescence (Krueger, 1999), a possobility that is indirectly consistent with the finding in behavior genetic studies that substance disorders have unique genetic loadings not shared with behavior disorders (Kendler et al., 2003) that vary in importance across the life course (Kendler et al., 2008).

A final factor analysis result that warrants comment is that the summary measure of eating disorders in the NCS-A loaded with behavior disorders rather than with distress disorders. Previous research has generally found that anorexia nervosa is more strongly related than bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder to internalizing disorders (e.g., Godart et al., 2006), while bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder are strongly related to behavioral disorders (e.g., Marmorstein et al., 2007). It is relevant in this regard that the vast majority of NCS-A respondents with eating disorders had bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder rather than anorexia nervosa.

The finding of stronger within-class than between-class predictive associations is consistent with previous longitudinal studies of prevalent disorders among youth (Costello et al., 2003; Newman et al., 1996; Reinke & Ostrander, 2008), although we are unaware of previous comparable studies of first onset of lifetime disorders. Comparable results were also found in our previous cross-national study of the development of comorbidity among adults (Kessler et al., 2011). The finding that fear disorders are the most important between-class predictors is consistent with, but goes beyond, previous research showing that early-onset anxiety disorders predict later distress disorders (Costello et al., 2003; Lewinsohn et al., 1995; Pine et al., 1998; Stein et al., 2001). Substance use disorders, at the other extreme, generally do not predict later disorders but are predicted strongly by earlier disorders. Although associations of behavior disorders with later substance disorders are well-documented (Costello et al., 1999; Fergusson et al., 2007), the predictive associations of primary fear and distress disorders have been less consistently examined (Costello et al., 2003).

The asymmetric associations across time-lagged disorder pairs could be due either to unmeasured common causes (e.g., genetic influences) or to causal influences of the predictor disorders on outcome disorders. There is no definitive way to distinguish these two possibilities with either retrospective or prospective non-experimental data. To the extent that the primary disorders are causes, though, successful early intervention might help prevent onset of subsequent comorbid disorders. To the extent that predictive associations are due to underlying common causes, temporally primary disorders might be useful risk markers (Kraemer et al., 1997) in targeting indicated interventions. Fear disorders stand out as especially important in the latter regard because they are such consistently strong predictors of later disorders. It is noteworthy in this regard that childhood-onset specific phobias can often be treated very effectively with inexpensive exposure-based therapies (Hamm, 2009; Gros & Anthony, 2006).

We are aware of no previous broad-based analysis of lifetime comorbidity predicting the subsequent first onset of a range of secondary disorders other than our own prior cross-national cross-section study of adults (Kessler et al., 2011). Our finding of largely sub-additive predictive associations of comorbid disorders, which we also found in our adult study, is consequently unique. It is important to note that this sub-additivity is based on a logistic model, though, which means that an additive specification with a linear or other link function might fit the data. However, our efforts to find an alternative link function that provided a better fit of the data with an additive specification was unsuccessful. This sub-additive pattern has potentially important implications for intervention because it suggests that intervening with a single comorbid disorder might not be effective in preventing subsequent disorder onset, as incremental predictive effects of individual disorders decrease with number of other disorders. To the extent that primary disorders are causes, treatment of the entire cluster of comorbid disorders is likely to be more effective than treatment of individual primary disorders in secondary prevention among patients with comorbidity (Moses & Barlow, 2006). Perhaps even more important, though, is that we showed that the innovative methodology used here yields substantively plausible results. Although many of these results do little more than replicate previous findings, the methodology has the potential to yield much more nuanced results when applied, as we hope it will be in the future, to prospective datasets.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220, R01-MH66627 and U01MH060220-09S1) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044780), and the John W. Alden Trust. The work of Dr. Merikangas is supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program. The work of Dr. Zaslavsky is supported by NIMH Grant R01-MH66627. A complete list of NCS-A publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. A public use version of the NCS-A dataset is available for secondary analysis. Instructions for accessing the dataset can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php. The NCS-A is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. The WMH Data Coordination Centres have received support from NIMH (R01-MH070884, R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, R01-MH077883), NIDA (R01-DA016558), the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, and the Pan American Health Organization. The WMH Data Coordination Centres have also received unrestricted educational grants from Astra Zeneca, BristolMyersSquibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Wyeth. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government. All authors had full access to the survey data. Kessler takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Kessler has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline Inc., HealthCore Inc., Health Dialog, Integrated Benefits Institute, John Snow Inc., Kaiser Permanente, Matria Inc., Mensante, Merck & Co, Inc., Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc., Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US Inc., SRA International, Inc., Takeda Global Research & Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly & Company, Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Analysis Group Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs., Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, and Shire US, Inc. The remaining authors report nothing to declare.

REFERENCES

- Alonso J, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Schoenbaum M, Bedirhan Ustun T, Rojas-Farreras S, Angermeyer M, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam AN, Kovess V, Levinson D, Liu Z, Medina-Mora ME, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Uda H, Kessler RC. Including information about co-morbidity in estimates of disease burden: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:873–886. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten EB, Biederman J, DiMauro A, Mick E, Monuteaux MC, Muehl K, Faraone SV. Methodological complexities in the diagnosis of major depression in youth: An analysis of mother and youth self-reports. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2001;11:395–407. doi: 10.1089/104454601317261573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Pine DS, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:47–57. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. 2nd Edition Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth. Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Prospective effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and sex on adolescent substance use and abuse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:1127–1134. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The comorbidities of adolescent problem behaviors: A latent class model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:339–354. doi: 10.1007/BF02168078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godart N, Berthoz S, Rein Z, Perdereau F, Lang F, Venisse JL, Halfon O, Bizouard P, Loas G, Corcos M, Jeammet P, Flament M, Curt F. Does the frequency of anxiety and depressive disorders differ between diagnostic subtypes of anorexia nervosa and bulimia? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:772–778. doi: 10.1002/eat.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Antony MM. The assessment and treatment of specific phobias: a review. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8:298–303. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halli SS, Rao KV, Halli SS. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. Plenum; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm AO. Specific phobias. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;32:577–591. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Murray C. Incremental validity in the psychological assessment of children and adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:496–507. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Schmitt E, Aggen SH, Prescott CA. Genetic and environmental influences on alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, and nicotine use from early adolescence to middle adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:674–682. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Üstün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell B-P, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2009a;18:69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009b;48:380–385. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, Gruber MJ, Guyer M, He Y, Jin R, Kaufman J, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009c;48:386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Little RJ, Groves RM. Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey nonresponse. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1995;17:192–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Stein DJ, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade L, Benjet C, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam A, Lee S, Lepine JP, Matchsinger H, Mihaescu-Pintia C, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Ustun TB. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:358–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Seeley JR. Adolescent psychopathology: IV. Specificity of psychosocial risk factors for depression and substance abuse in older adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1221–1229. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Isensee B, von Sydow K, Wittchen HU. The Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study (EDSP): A methodological update. European Addiction Research. 2000;6:170–182. doi: 10.1159/000052043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. In: Buck C, Liopis A, Najera E, Terris M, editors. The Challenge of Epidemiology: Issues and Selected Readings. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO); Washington, DC: 1988. pp. 533–553. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, von Ranson KM, Iacono WG, Succop PA. Longitudinal associations between externalizing behavior and dysfunctional eating attitudes and behaviors: a community-based study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:87–94. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Anderson J. DSM-III disorders from age 11 to age 15 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:50–59. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Koretz D, Kessler RC. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:367–369. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819996f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Moffit TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton WR. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:552–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Latent trajectory classes of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB. Accumulation of major depressive episodes over time in a prospective study indicates that retrospectively assessed lifetime prevalence estimates are too low. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Ostrander R. Heterotyic and homotypic continuity: The moderating effects of age and gender. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1109–1121. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute . SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis, version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: A 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, von Korff M. Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: Implications for epidemiologic research. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1995;17:221–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: A prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Baratta MV, Abrantes AM, Brown SA. Attention dysfunction predicts substance involvement in community youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:680–686. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: Why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Perkonigg A, Lachner G, Nelson CB. Early developmental stages of psychopathology study (EDSP): objectives and design. European Addiction Research. 1998;4:18–27. doi: 10.1159/000018921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]