Abstract

The molecular mechanisms of the mammalian gustatory system have been examined in many studies using rodents as model organisms. In this study, we examined the mRNA expression of molecules involved in taste signal transduction in the fungiform papillae (FuP) and circumvallate papillae (CvP) of the rhesus macaque, Macaca mulatta, using in situ hybridization. TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS2Rs, and PKD1L3 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of taste receptor cells (TRCs) in the FuP and CvP. This finding suggests that TRCs sensing different basic taste modalities are mutually segregated in macaque taste buds. Individual TAS2Rs exhibited a variety of expression patterns in terms of the apparent level of expression and the number of TRCs expressing these genes, as in the case of human TAS2Rs. GNAT3, but not GNA14, was expressed in TRCs of FuP, whereas GNA14 was expressed in a small population of TRCs of CvP, which were distinct from GNAT3- or TAS1R2-positive TRCs. These results demonstrate similarities and differences between primates and rodents in the expression profiles of genes involved in taste signal transduction.

Introduction

The five basic taste modalities, namely, sweet, bitter, umami (savory), sour, and salty, are detected by taste receptors that are localized at the apical ends of taste receptor cells (TRCs) that form taste buds [1], [2], [3]. Previous studies, mainly in rodents, have demonstrated that sweet, bitter, and umami tastes are mediated by two families of G protein-coupled receptors: T1rs and T2rs [1], [3]. T1r1 and T1r2 form heteromers with T1r3 to function as umami and sweet taste receptors, respectively [4], [5], [6]. The Tas2rs, which encode bitter taste receptors, comprise approximately 30 members in mammals [7], [8], [9]. Acting as downstream signal transduction molecules, two G protein α subunits, Gnat3 (which encodes gustducin) and Gna14, phospholipase C-β2 (Plcb2), and transient receptor potential melastatin-5 (Trpm5) are expressed in subsets of TRCs and play important roles in taste signal transduction [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Polycystic kidney disease 1-like 3 (Pkd1l3) and polycystic kidney disease 2-like 1 (Pkd2l1) are expressed in sour-sensing TRCs [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Expression analysis demonstrated that certain genes involved in taste signal transduction exhibited different expression patterns between the fungiform papillae (FuP) and the circumvallate papillae (CvP), which are located on the anterior and posterior regions of the tongue, respectively; Tas1r1 was expressed primarily in the FuP, whereas Tas1r2, Tas2rs, Pkd1l3, and Gna14 were expressed primarily in the CvP [7], [10], [13], [17], [19], [21]. In contrast, Tas1r3, Pkd2l1, Gnat3, Plcb2, and Trpm5 were expressed in both the FuP and the CvP [4], [14], [17], [19], [22].

The expression profiles of genes involved in taste signal transduction have been partially uncovered in primates, including humans [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. In situ hybridization (ISH) demonstrated that human TAS2Rs were expressed in heterogeneous populations of TRCs [23], whereas the expression of multiple Tas2rs occurred in the same subset of TRCs in mice [7]. On the other hand, Matsunami and colleagues demonstrated that each Tas2r was expressed in a much smaller number of TRCs than Gnat3 in mice [9]. The tissue distribution of expression of genes involved in taste signal transduction, including TAS1Rs, TAS2Rs, PKDs, and TRPM5, was examined in the CvP of the cynomolgus macaque, Macaca fascicularis [24], but the co-expression relationships among these genes largely remain to be elucidated. Moreover, the tissue distribution of expression of the majority of genes in the FuP has not been examined by ISH, except for PKD1L3 and TRPM5 [25].

In this study, we examined the mRNA expression of genes involved in taste signal transduction in more detail in the FuP and CvP of the rhesus macaque, Macaca mulatta, by ISH. We compared the gene expression profiles in the FuP and CvP and examined the co-expression relationships among various genes. We found both similarities and differences between macaques and rodents. This study may provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying taste sensation in primates, including humans.

Materials and Methods

Macaques

This study was carried out in strict accordance with recommendations in the Guide for Care and Use of Nonhuman Primates of the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University (Version 3, issued in 2010). This guideline was prepared based on the provisions of the Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments (June 1, 2006; Science Council of Japan), Basic Policies for the Conduct of Animal Experiments in Research Institutions under the Jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (effective on June 1, 2006; Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW)), Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions (Notice No. 71 of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) dated June 1, 2006), and Standards Relating to the Care and Management of Laboratory Animals and Relief of Pain (Notice No. 88 of the Ministry of the Environment dated April 28, 2006). All of the animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University (Permit Numbers: 2010-C-24 and 2011-B-17). Briefly, animals were kept in cages with sufficient space (780 mm wide, 650 mm depth, and 800 mm height) in the air conditioned room with sufficient environmental enrichment. The animals were housed in 12-hour light-dark cycle conditions with a daytime light intensity of 150–300 lux and their intake of water, food, or selected nutrients was not restricted. In addition to normal pellet foods, the animals were occasionally fed sweet potatoes, fruits, and vegetables for nutrimental enrichment. To ameliorate suffering, anesthesia was induced by intramuscular injection of ketamine (2.5 mg/kg) with medetomidine (0.1 mg/kg) into the femoral or brachial muscle of the animals at the initial step of the experiments. After the animals were anesthetized and immobilized, pentobarbital sodium (25 mg/kg) was infused intravenously on the autopsy table. After the animals were deeply anesthetized, which was confirmed by the absence of pain response, they were sacrificed by bloodletting from the jugular vein. After a sufficient amount of time had elapsed, respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, and pupillary dilatation were confirmed. Then, taste tissues from five rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta; approximately 3-year-old males), which were scheduled for euthanasia not only for this study but also for other experimental purposes, were collected and embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan) by ourselves. All the experiments described above were performed at Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University.

Database Search and Cloning

The TBLASTN program was used to search for genomic sequences showing significant identity with human TAS1Rs, TAS2Rs, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2 in the public genome database of the rhesus macaque (http://www.ensembl.org/Macaca_mulatta/Info/Index). The macaque TAS2Rs were named following the nomenclature proposed by Dong et al [28]. The cDNA sequence corresponding to G756-E852 of T1R3, which was unknown due to the lack of a genomic sequence, was obtained by 3′-RACE using 3′-Full RACE Core Set (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). The entire coding regions of TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, TAS2Rs, GNAT3, and GNA14 and partial coding regions of PKD1L3 (C42-Y749) and PLCB2 (M1-K192), which were amplified from macaque cDNA synthesized from epithelial tissues containing circumvallate papillae or genomic DNA extracted from tongue tissue, were used as probes.

In Situ Hybridization (ISH)

Fresh frozen sections of tongue, 10 µm thick, were placed on MAS-coated glass slides (Matsunami Glass, Kishiwada, Japan). For ISH, the sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with proteinase K (6.4 µg/ml for 5 min) followed by acetylation. Prehybridization (at 58°C for 1 hour), hybridization (at 58°C, 2 O/N), washing (0.2 x SSC at 58°C), and development (NBT-BCIP) were performed using digoxigenin-labeled probes as described previously [17]. Double-label fluorescence ISH was performed with digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labeled RNA probes as described previously [29]. In brief, the probes were detected by incubation with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated anti-fluorescein antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), followed by incubation with TSA-AlexaFluor 555 and TSA-AlexaFluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using the tyramide signal amplification method. Stained images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a cooled CCD digital camera (DP71; Olympus) or a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV500; Olympus).

Results and Discussion

Expression of Taste Receptors and Signal Transduction Molecules in the Fungiform and Circumvallate Papillae

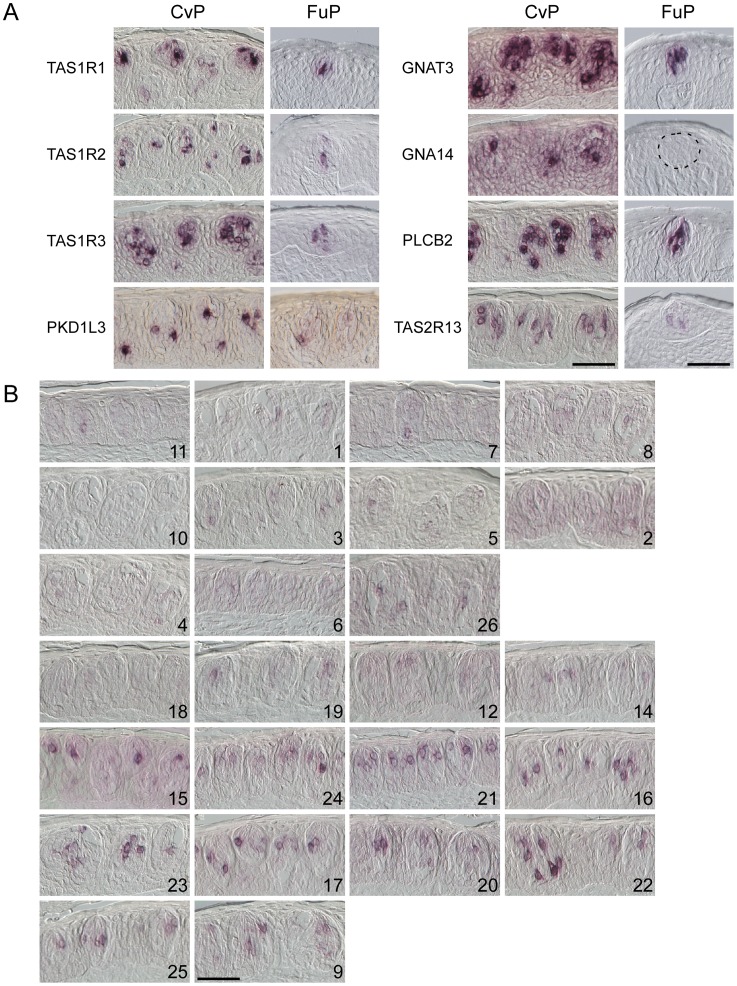

To examine the tissue distributions of expression of genes involved in taste signal transduction, we conducted in situ hybridization on sections of the FuP and CvP using the following genes as probes: TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, TAS2Rs, PKD1L3, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2. In the CvP, three TAS1Rs, PKD1L3, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2 were robustly expressed in subsets of TRCs (Figure 1A). Certain TAS2Rs, such as TAS2R13, were robustly expressed in subsets of TRCs, whereas only weak signals were observed for other TAS2Rs, including those located on chromosomes 3 and 6 (Figures 1A and B; Figure S1). In the FuP, three TAS1Rs, GNAT3, and PLCB2, but not GNA14, were robustly expressed in subsets of TRCs, whereas TAS2R13 and PKD1L3 were weakly expressed in subsets of TRCs (Figure 1A). It should be noted that TAS1R1, TAS1R2, and TAS2R13, as well as PKD1L3 [25], were expressed in both the FuP and the CvP.

Figure 1. The mRNA expression of genes encoding taste receptors and signal transduction molecules in the fungiform and circumvallate papillae of the rhesus macaque.

(A) In situ hybridization revealed that three TAS1Rs, TAS2R13, PKD1L3, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2 were robustly expressed in subsets of the TRCs in the CvP. These genes, except for GNA14, were also expressed in subsets of the TRCs in the FuP. n≥2 (numbers of sections ≥4) for TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, PKD1L3, GNAT3, and TAS2R13 in CvP, n = 1 (numbers of sections ≥2) for GNA14 and PLCB2 in CvP, n≥2 (numbers of sections ≥20) for TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, PKD1L3, and GNA14 in FuP, n = 1 (numbers of sections ≥10) for GNAT3, PLCB2, and TAS2R13 in FuP. (B) The TAS2Rs located on chromosome 11 (TAS2R9 and TAS2R12-25) appeared to be robustly expressed in subsets of TRCs, whereas only weak signals were observed for the TAS2Rs located on chromosomes 3 (TAS2R1-8 and TAS2R10-11) and 6 (TAS2R26). Tas2Rs are arranged according to the locations on the chromosomes (see Figure S1). n = 2 (numbers of sections ≥4) for TAS2R1-8, 10-11, 21, 23, and 26, n = 1 (numbers of sections ≥2) for TAS2R9, 12, 14-20, 22, and 24-25. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Co-expression Relationships among Taste Signal Transduction Molecules

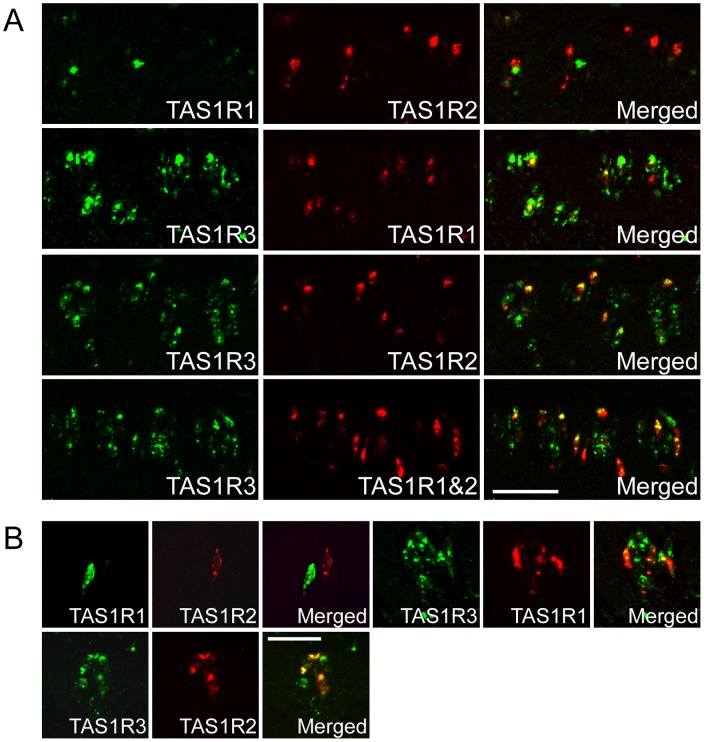

To compare the TRCs expressing each taste signal transduction molecule, we next performed double-label fluorescence ISH. T1R1 and T1R2 form heteromers with T1R3 to function as umami (savory) and sweet taste receptors, respectively [4], [5], [30]. TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of TAS1R3-positive TRCs in the FuP and CvP (Figure 2; Tables S1 and S2). In the CvP, approximately 20% and 40% of TAS1R3-positive TRCs were also positive for TAS1R1 and TAS1R2, respectively. Experiments using a mixed probe for TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 combined with a probe for TAS1R3 confirmed that approximately 40% of TAS1R3-positive TRCs were negative for both TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 (Figure 2A and data not shown). In the FuP, approximately 40% and 30% of TAS1R3-positive TRCs were also positive for TAS1R1 and TAS1R2, respectively (Figure 2B; Table S2). In summary, TAS1R3-positive TRCs in the FuP and CvP can be classified into three types of cells: cells expressing TAS1R1+TAS1R3, those expressing TAS1R2+TAS1R3, and those expressing TAS1R3 alone.

Figure 2. The co-expression relationships among three TAS1Rs.

(A) TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of the TAS1R3-positive TRCs in the CvP. In situ hybridization using a mixed probe for TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 combined with a probe for TAS1R3 revealed the presence of TRCs expressing TAS1R3 alone. n = 2 (numbers of sections ≥4). (B) TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of the TAS1R3-positive TRCs in the FuP. The TAS1R3-positive TRCs in the FuP and CvP were classified into three types of cells: cells expressing TAS1R1+TAS1R3, those expressing TAS1R2+TAS1R3, and those expressing TAS1R3 alone. n = 1 or 2 (numbers of sections ≥10). Scale bars: 50 µm.

A previous gene expression analysis using microarrays in the taste buds of the cynomolgus macaque collected by laser capture microdissection revealed that TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were more highly expressed in the taste buds of the FuP than in those of the CvP [24]. Our ISH analysis quantified the expression of the genes involved in taste signal transduction at the cellular mRNA level. Consequently, the majority of genes, including TAS1R1 and TAS1R2, showed more uniform expression patterns in the FuP and the CvP of macaques than in those of rodents. These results are consistent with previous findings from gustatory nerve recordings in the rhesus macaque showing that both the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves, which innervate the FuP and CvP, respectively, responded to a variety of basic taste compounds [31].

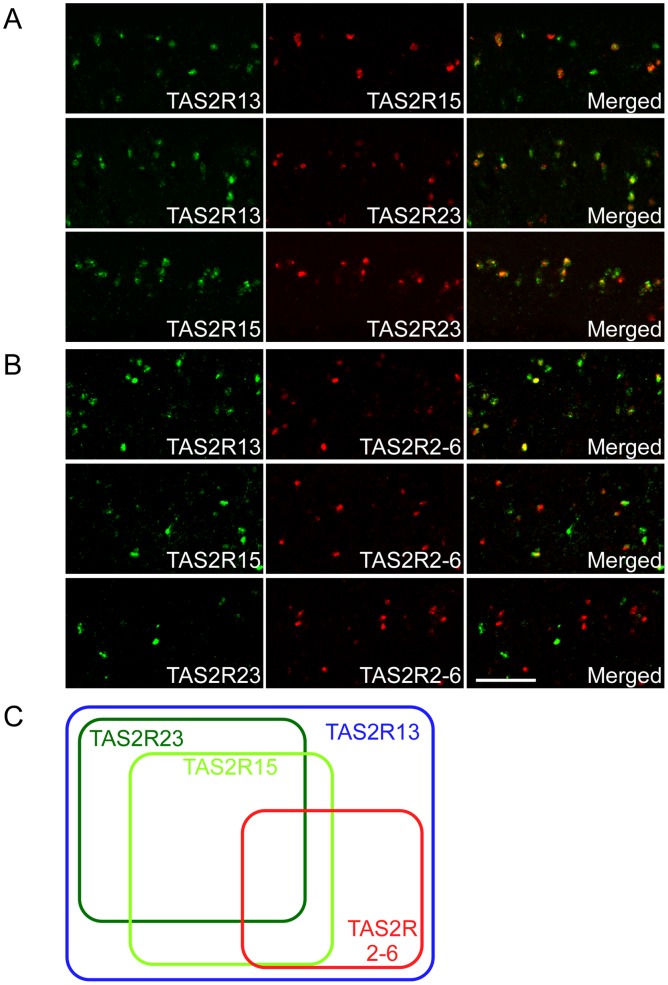

TAS2R13, TAS2R15, and TAS2R23, which were robustly expressed in subsets of the TRCs in the CvP (Figure 1B), reside in different TAS2R gene clusters on chromosome 11 [28] (Figure S1; http://www.ensembl.org/Macaca_mulatta/Info/Index). Almost all the TAS2R15- and TAS2R23-positive TRCs were also positive for TAS2R13, whereas TAS2R15-positive TRCs partially overlapped with those expressing TAS2R23 (Figure 3A; Table S3). We used a mixed probe for TAS2R2, TAS2R3, TAS2R4, TAS2R5, and TAS2R6 because only weak signals were detected for each TAS2R located on chromosome 3 (Figure 1B). When we compared the TRCs expressing TAS2Rs located on different chromosomes, almost all the TRCs labeled with the mixed probe were also positive for TAS2R13, but they partially overlapped with TRCs expressing TAS2R15 or TAS2R23 (Figure 3B; Table S3). These results demonstrate that each TRC sensing bitter compounds expresses various combinations of TAS2Rs (Figure 3C), as in the case of human TAS2Rs [23].

Figure 3. The co-expression relationships among TAS2Rs.

(A) TAS2R13, TAS2R15, and TAS2R23 reside in different TAS2R gene clusters on chromosome 11. Almost all of the TAS2R15- and TAS2R23-positive TRCs were also positive for TAS2R13, whereas TAS2R15-positive TRCs partially overlapped with those expressing TAS2R23. n = 1 or 2 (numbers of sections ≥2). (B) When we compared the TRCs expressing TAS2Rs located on different chromosomes, almost all of the TRCs labeled with a mixed probe for TAS2R2-6 were also positive for TAS2R13, but they partially overlapped with the TRCs expressing TAS2R15 or TAS2R23. n = 1 or 2 (numbers of sections ≥2). (C) A Venn diagram illustrating the co-expression relationships among the TAS2Rs. Each TRC sensing bitter compounds expresses various combinations of TAS2Rs. Scale bar: 50 µm.

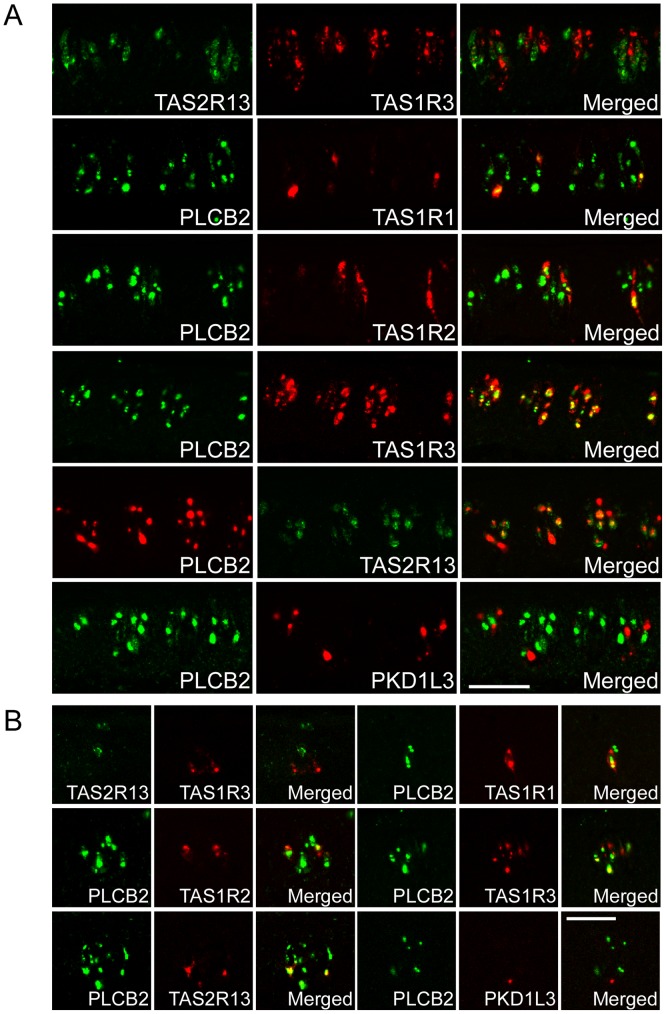

We next compared the TRCs expressing taste receptors for different basic taste modalities. We chose TAS2R13 as a representative TAS2R because almost all the TRCs expressing other TAS2Rs that we tested were included in the TAS2R13-positive TRCs, as described above (Figure 3; Table S3). TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of TAS1R3-positive TRCs (Figure 2). TAS1R3-positive TRCs were negative for TAS2R13 in the CvP (Figure 4A) and in the FuP (Figure 4B). TAS1R1-, TAS1R2-, TAS1R3-, and TAS2R13-positive TRCs were also positive for PLCB2 in the CvP (Figure 4A; Table S1) and in the FuP (Figure 4B), as in the case of other vertebrates such as rodents and fish [29], [32]. PLCB2-positive TRCs were negative for PKD1L3 in the CvP (Figure 4A) and in the FuP (Figure 4B). In summary, TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS2Rs, and PKD1L3 were exclusively expressed in different subsets of the TRCs in the FuP and CvP (Figure 5D). Thus, these results suggest that the TRCs detecting different basic taste modalities are mutually segregated in macaque taste buds.

Figure 4. The co-expression relationships among taste receptors.

(A) In the CvP, the TAS1R3-positive TRCs were negative for TAS2R13. The PLCB2-positive TRCs, which include TAS1R1-, TAS1R2-, TAS1R3-, and TAS2R13-positive TRCs, were negative for PKD1L3. n = 1 (numbers of sections ≥2). (B) In the FuP, the TAS1R3-positive TRCs were negative for TAS2R13. The PLCB2-positive TRCs, which include TAS1R1-, TAS1R2-, TAS1R3-, and TAS2R13-positive TRCs, were negative for PKD1L3. n = 1 or 2 (numbers of sections ≥10). Scale bars: 50 µm.

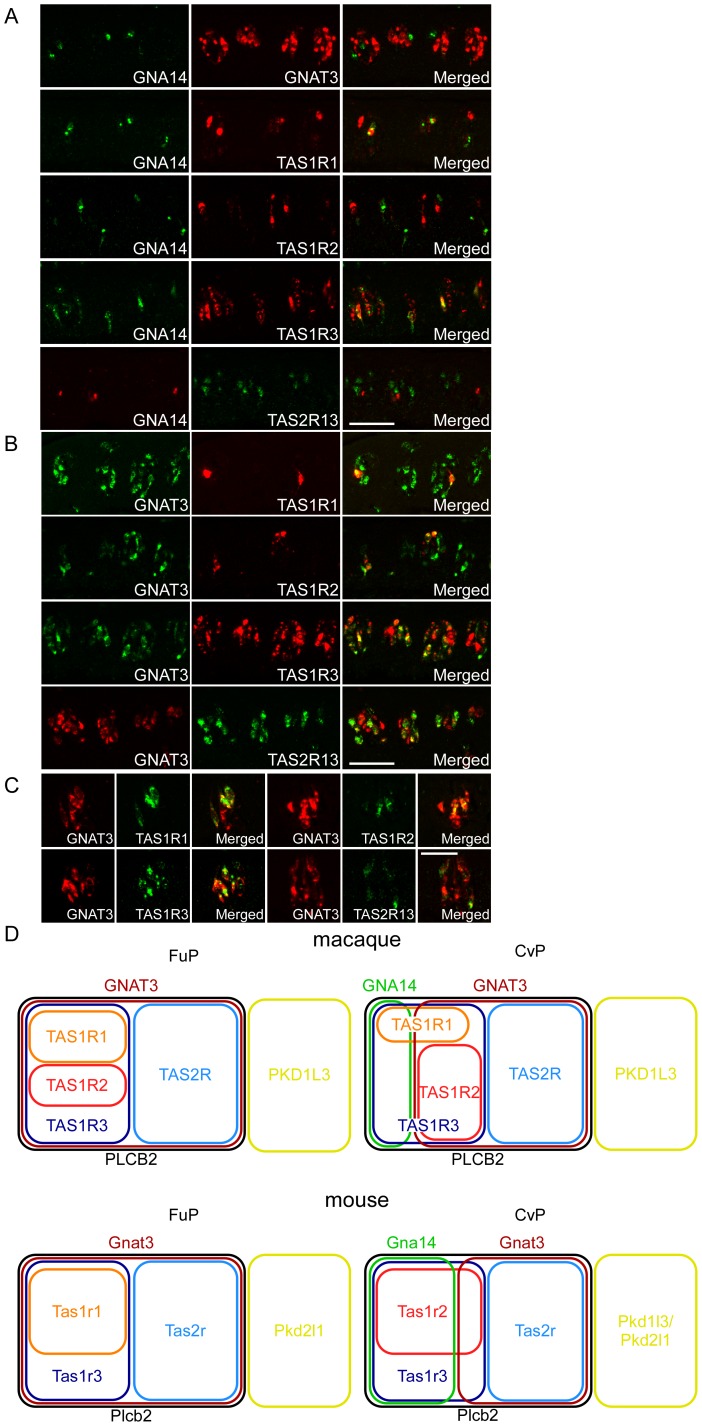

Figure 5. The co-expression relationships among taste receptors and G protein α subunits.

(A) In the CvP, GNA14 was expressed in a much smaller population of TRCs than GNAT3 and in a mutually exclusive manner. The GNA14–positive TRCs were distinct from those expressing TAS1R2 and TAS2R13, but they were subsets of the TAS1R3-positive TRCs and partially overlapped with the TAS1R1-positive TRCs. n ≥1 (numbers of sections ≥2). (B) In the CvP, TAS1R2 and TAS2R13 were expressed in subsets of the GNAT3–positive TRCs, which partially overlapped with the TAS1R1- and TAS1R3-positive TRCs. n ≥2 (numbers of sections ≥4). (C) In the FuP, TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, and TAS2R13 were expressed in subsets of GNAT3-positive TRCs. n ≥1 (numbers of sections ≥10). (D) Venn diagram illustrating the co-expression relationships among taste receptors and signal transduction molecules in the macaque and the mouse. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Finally, we focused on two genes encoding G protein α subunits, GNAT3 and GNA14, which are specifically expressed in subsets of rodent TRCs [10], [13], [22], [33]. In the CvP, GNA14 was expressed in a much smaller population of TRCs than GNAT3 and in a mutually exclusive manner (Figures 1A and 5A; Table S1). GNA14–positive TRCs were distinct from those expressing TAS1R2 and TAS2R13, but they formed subsets of TAS1R3-positive TRCs and partially overlapped with TAS1R1-positive TRCs (Figure 5A; Table S1). In contrast, TAS1R2 and TAS2R13 were expressed in different subsets of GNAT3–positive TRCs, which partially overlapped with TAS1R1- and TAS1R3-positive TRCs (Figure 5B; Table S1). It should be noted that TAS1R2 was co-expressed with GNAT3 but not with GNA14 in macaques, whereas Tas1r2 was primarily co-expressed with Gna14 but not with Gnat3 in rodents [10], [13], [22]. In the FuP, GNAT3, but not GNA14, was expressed in TRCs (Figure 1A). TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, and TAS2R13 were expressed in subsets of GNAT3-positive TRCs (Figure 5C; Table S2). These results suggest that GNAT3 plays a pivotal role in mediating sweet, bitter, and umami tastes in macaques.

Conclusions

We investigated the expression of taste receptors and signal transduction molecules in the FuP and CvP of the rhesus macaque and further examined the co-expression relationships among these genes. The majority of genes exhibited more uniform expression patterns in the macaque FuP and CvP than in these papillae in rodents (Figure 5D). Intriguingly, there were several differences between the expression profiles of macaques and rodents. First, TAS1R1 and TAS1R2 were more uniformly expressed in both the FuP and the CvP of macaques than in rodents. Second, TAS1R2 was co-expressed with GNAT3 in the CvP but not with GNA14. Third, macaque TAS2Rs were expressed in heterogeneous populations of TRCs in the CvP. These results suggest that the molecular mechanisms underlying taste transduction in primates, including humans, may be different from those in rodents and that the macaque is an important model organism for taste perception in humans.

Supporting Information

Schematic drawing illustrating the locations of macaque TAS2Rs on the chromosomes. TAS2R1-8, TAS2R11, and TAS2R38 are located on chromosome 3, whereas only TAS2R26 is located on chromosome 6. The other 15 TAS2Rs are located on chromosome 11, although precise location of TAS2R9 has not been determined. TAS2R13, TAS2R15, and TAS2R23 reside in different TAS2R gene clusters on the chromosome 11.

(TIF)

The percentages of TAS1Rs, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2 co-expression in the circumvallate taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)

The percentages of TAS1Rs, TAS2R13, and GNAT3 co-expression in the fungiform taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)

The percentages of TAS2R co-expression in the circumvallate taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) 22688010 to Y.I. and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 20380183 to K.A. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; the Cooperation Research Program of the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University to Y.I.; and a Research and Development Program for New Bio-industry Initiatives to K.A. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ishimaru Y (2009) Molecular mechanisms of taste transduction in vertebrates. Odontology 97: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ishimaru Y, Matsunami H (2009) Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels and taste sensation. J Dent Res 88: 212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yarmolinsky DA, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ (2009) Common sense about taste: from mammals to insects. Cell 139: 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nelson G, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Zhang Y, Ryba NJ, et al. (2001) Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 106: 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, et al. (2002) An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 416: 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, et al. (2003) The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell 115: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adler E, Hoon MA, Mueller KL, Chandrashekar J, Ryba NJ, et al. (2000) A novel family of mammalian taste receptors. Cell 100: 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, et al. (2000) T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100: 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsunami H, Montmayeur JP, Buck LB (2000) A family of candidate taste receptors in human and mouse. Nature 404: 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tizzano M, Dvoryanchikov G, Barrows JK, Kim S, Chaudhari N, et al. (2008) Expression of Galpha14 in sweet-transducing taste cells of the posterior tongue. BMC Neurosci 9: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perez CA, Huang L, Rong M, Kozak JA, Preuss AK, et al. (2002) A transient receptor potential channel expressed in taste receptor cells. Nat Neurosci 5: 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong GT, Gannon KS, Margolskee RF (1996) Transduction of bitter and sweet taste by gustducin. Nature 381: 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shindo Y, Miura H, Carninci P, Kawai J, Hayashizaki Y, et al. (2008) G alpha14 is a candidate mediator of sweet/umami signal transduction in the posterior region of the mouse tongue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 376: 504–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Cook B, et al. (2003) Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. Cell 112: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kawaguchi H, Yamanaka A, Uchida K, Shibasaki K, Sokabe T, et al. (2010) Activation of polycystic kidney disease-2-like 1 (PKD2L1)-PKD1L3 complex by acid in mouse taste cells. J Biol Chem 285: 17277–17281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoshida R, Miyauchi A, Yasuo T, Jyotaki M, Murata Y, et al. (2009) Discrimination of taste qualities among mouse fungiform taste bud cells. J Physiol 587: 4425–4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ishimaru Y, Inada H, Kubota M, Zhuang H, Tominaga M, et al. (2006) Transient receptor potential family members PKD1L3 and PKD2L1 form a candidate sour taste receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 12569–12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kataoka S, Yang R, Ishimaru Y, Matsunami H, Sevigny J, et al. (2008) The candidate sour taste receptor, PKD2L1, is expressed by type III taste cells in the mouse. Chem Senses 33: 243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang AL, Chen X, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Guo W, et al. (2006) The cells and logic for mammalian sour taste detection. Nature 442: 934–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang YA, Maruyama Y, Stimac R, Roper SD (2008) Presynaptic (Type III) cells in mouse taste buds sense sour (acid) taste. J Physiol 586: 2903–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoon MA, Adler E, Lindemeier J, Battey JF, Ryba NJ, et al. (1999) Putative mammalian taste receptors: a class of taste-specific GPCRs with distinct topographic selectivity. Cell 96: 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim MR, Kusakabe Y, Miura H, Shindo Y, Ninomiya Y, et al. (2003) Regional expression patterns of taste receptors and gustducin in the mouse tongue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312: 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Behrens M, Foerster S, Staehler F, Raguse JD, Meyerhof W (2007) Gustatory expression pattern of the human TAS2R bitter receptor gene family reveals a heterogenous population of bitter responsive taste receptor cells. J Neurosci 27: 12630–12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hevezi P, Moyer BD, Lu M, Gao N, White E, et al. (2009) Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in primate taste buds reveals links to diverse processes. PLoS One 4: e6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moyer BD, Hevezi P, Gao N, Lu M, Kalabat D, et al. (2009) Expression of genes encoding multi-transmembrane proteins in specific primate taste cell populations. PLoS One 4: e7682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Max M, Shanker YG, Huang L, Rong M, Liu Z, et al. (2001) Tas1r3, encoding a new candidate taste receptor, is allelic to the sweet responsiveness locus Sac. Nat Genet 28: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang H, Iguchi N, Rong Q, Zhou M, Ogunkorode M, et al. (2009) Expression of the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ1 in mammalian taste bud cells and the effect of its null-mutation on taste preferences. J Comp Neurol 512: 384–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dong D, Jones G, Zhang S (2009) Dynamic evolution of bitter taste receptor genes in vertebrates. BMC Evol Biol 9: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishimaru Y, Okada S, Naito H, Nagai T, Yasuoka A, et al. (2005) Two families of candidate taste receptors in fishes. Mech Dev 122: 1310–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu H, Staszewski L, Tang H, Adler E, Zoller M, et al. (2004) Different functional roles of T1R subunits in the heteromeric taste receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 14258–14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hellekant G, Danilova V, Ninomiya Y (1997) Primate sense of taste: behavioral and single chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerve fiber recordings in the rhesus monkey, Macaca mulatta. J Neurophysiol 77: 978–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyoshi MA, Abe K, Emori Y (2001) IP(3) receptor type 3 and PLCbeta2 are co-expressed with taste receptors T1R and T2R in rat taste bud cells. Chem Senses 26: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McLaughlin SK, McKinnon PJ, Margolskee RF (1992) Gustducin is a taste-cell-specific G protein closely related to the transducins. Nature 357: 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic drawing illustrating the locations of macaque TAS2Rs on the chromosomes. TAS2R1-8, TAS2R11, and TAS2R38 are located on chromosome 3, whereas only TAS2R26 is located on chromosome 6. The other 15 TAS2Rs are located on chromosome 11, although precise location of TAS2R9 has not been determined. TAS2R13, TAS2R15, and TAS2R23 reside in different TAS2R gene clusters on the chromosome 11.

(TIF)

The percentages of TAS1Rs, GNAT3, GNA14, and PLCB2 co-expression in the circumvallate taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)

The percentages of TAS1Rs, TAS2R13, and GNAT3 co-expression in the fungiform taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)

The percentages of TAS2R co-expression in the circumvallate taste buds. The percentage values were calculated by dividing the number of cells expressing both gene X and gene Y by the number of cells expressing gene X.

(DOCX)