Abstract

Cell migration on planar surfaces is driven by cycles of actin protrusion, integrin-mediated adhesion, and myosin-mediated contraction; however, this mechanism may not accurately describe movement in 3-dimensional (3D) space. By subjecting cells to restrictive 3D environments, we demonstrate that physical confinement constitutes a biophysical stimulus that alters cell morphology and suppresses mesenchymal motility in human breast carcinoma (MDA-MB-231). Dorsoventral polarity, stress fibers, and focal adhesions are markedly attenuated by confinement. Inhibitors of myosin, Rho/ROCK, or β1-integrins do not impair migration through 3-μm-wide channels (confinement), even though these treatments repress motility in 50-μm-wide channels (unconfined migration) by ≥50%. Strikingly, confined migration persists even when F-actin is disrupted, but depends largely on microtubule (MT) dynamics. Interfering with MT polymerization/depolymerization causes confined cells to undergo frequent directional changes, thereby reducing the average net displacement by ≥80% relative to vehicle controls. Live-cell EB1-GFP imaging reveals that confinement redirects MT polymerization toward the leading edge, where MTs continuously impact during advancement of the cell front. These results demonstrate that physical confinement can induce cytoskeletal alterations that reduce the dependence of migrating cells on adhesion-contraction force coupling. This mechanism may explain why integrins can exhibit reduced or altered function during migration in 3D environments.—Balzer, E. M., Tong, Z., Paul, C. D., Hung, W.-C., Stroka, K. M., Boggs, A. E., Martin, S. S., Konstantopoulos, K. Physical confinement alters tumor cell adhesion and migration phenotypes.

Keywords: mesenchymal, microtubules, actin, cytoskeleton

During movement through tissues, capillaries, and lymph nodes, cells experience varying degrees of physical confinement. Meanwhile, conventional wisdom regarding the mechanisms of cell migration has derived predominantly from studies on unconfined 2-dimensional (2D) extracellular matrix (ECM). In mesenchymal motility, cells coordinate actin-based protrusion with the formation of actomyosin-associated focal adhesions (FAs) through which contractile forces are transduced to the underlying substrate (1). This mechanism is predicated on dorsoventral polarization, which enables the formation of lamellipodia and contractile stress fibers. However, 2D environments naturally overemphasize the prominence of these structures, many of which are suppressed or absent in 3-dimensional (3D) environments (2–5). Indeed, integrin-independent movement (6, 7) and a lack of FAs (8, 9) have been observed in reconstituted ECM gels, indicating that the function of substrate adhesions is modified in 3D environments (10).

A major pitfall of 2D environments is that they do not incorporate physical constraints, which are inherent in 3D environments. Cells confined in 3D space secrete proteases to locally remodel the ECM or adapt in the absence of proteolysis by switching to an amoeboid style of integrin-independent movement and utilizing preexisting gaps in the ECM (11). Although it is clear that migrating tumor cells exhibit migratory plasticity, the question of how they adapt has not been definitively answered. Gel assays have been increasingly utilized to study migration in 3D environments. However, mechanistic differences in cell migration have been observed between 2D vs. 3D gel assays, which may be attributed to intracellular signaling in response to proteolysis and ECM remodeling required prior to cell migration in 3D gels; the stiffness of ECM; the porosity (i.e., physical confinement) of ECM; or a combination of all these factors.

To isolate the effects of physical confinement on cell motility, we used an engineered microfluid-based migration chamber, which consists of 4-walled channels through which cells are induced to migrate in response to a chemotactic stimulus. Specifically, tumor cells were induced to migrate through microchannels of fixed height (10 μm) and variable width (50, 20, 10, 6, and 3 μm); thus, they were subjected to varying degrees of lateral (x) confinement. Cells migrated through all channels, but the degree of confinement determined the migratory phenotype. In particular, confinement in 3-μm-wide channels suppressed dorsoventral polarity and the appearance of FAs. Migration in confinement was independent of myosin-mediated contraction and β1-integrins, and even actin polymerization was not required. In contrast, inhibitors of microtubule (MT) dynamics significantly reduced the speed and directionality of confined cells. We demonstrate that MTs are physically redirected toward the migratory front in confinement. These findings emphasize that confinement induces cytoskeletal alterations that preclude the formation of 2D adhesion and contraction structures and reduce the role of force coupling in cell migration. This biological response to a physical stimulus may provide a mechanistic basis on which to interpret the discrepancies between migratory phenotypes in 2D and 3D environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma, SW1990 and Pa0C3 pancreatic carcinoma, and human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). All cells were maintained in 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. Basal medium was supplemented with 2.5 μg/ml CT04 (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO, USA); 20 μM ML-7, 30 μM Y-27632, 50 μM blebbistatin, 2.5 μM latrunculin-A (LA), 20 μM cytochalasin D (CD), 1.2 μM Taxol, or 125 μM colchicine (each from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA); 20 μg/ml anti-human β1-integrin (P4C10; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), vehicle (≤0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide, ethanol, or dimethyl sulfoxide+ethanol) or isotype controls (mouse IgG; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Transfections for myosin IIa siRNA experiments were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Myosin IIa siRNA oligos were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-61120; Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and cells were checked for knockdown at 24 and 48 h via Western blot analysis with a myosin IIa antibody (Sigma; M8064) and compared to an internal control (anti-β-actin, A5441; Sigma).

Fabrication of the microchannel device

A 10-μm-thick layer of SU-8 photoresist was deposited on a mechanical-grade silicon wafer and cross-linked by filtering UV light through a photomask. Non-cross-linked SU-8 was removed with SU-8 developer, and the wafer was rinsed with isopropyl alcohol. This process was repeated with a 50-μm-thick layer of SU-8 and a second photomask to overlay two 400-μm-wide channels, spaced either 200 or 400 μm apart. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was combined at a 10:1 ratio with PDMS-curing agent, poured over the silicon master, and incubated in a sealed vacuum container for 2 h. The PDMS was baked for 30 min at 95°C, peeled off of the negative master, cut to 25 × 35 mm (w×l) and pierced to form inlet and outlet ports. The PDMS device and a 75-mm glass coverslip were activated by oxygen plasma treatment for 2 min and irreversibly sealed. Type collagen I (20 μg/ml in PBS) was added, and the entire device was incubated at 37% for 1 h to adsorb collagen.

Microchannel seeding and cell migration

The process is summarized by Tong et al. (12). Briefly, cells were detached with trypsin, washed with PBS, and suspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml. A 50-μl volume (1×105 cells) was added to the cell inlet port, and the cells were transported along the seeding channel by pressure-induced flow. Within 5 min, the cell suspension was removed and replaced with serum-free medium, which was also placed in the upper inlets. The topmost inlet received serum-containing medium to generate a chemoattractant gradient. The device was placed in an incubator or incubated chamber (5% CO2/95% air; TIZ, Tokaihit Co., Fujinomiya, Japan) on an inverted microscope stage. Migration along the chemoattractant gradient was recorded at multiple-stage positions via stage automation (Nikon Elements; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Each experiment was repeated ≥3 times; image series were then exported to ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD, USA) for quantification of cell size, speed, and directionality. To calculate instantaneous cell velocity, the cell center was identified as the midpoint between poles of the cell body and tracked for changes in x, y position at 6 consecutive 20-min intervals to generate an average value; this process was repeated for ≥50 cells/condition/experimental trial.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized for 5 min in 0.25% Triton X-100, and blocked for 1 h at ambient temperature with 2.5% BSA and 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630. Primary antibody solutions were then added, according to the following specifications: mouse α-paxillin (1:200; Invitrogen), rabbit α-tyrosine-phosphorylated paxillin (α-pY-paxillin; Tyr118; 1:100; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA), mouse α-tyrosine-phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (α-pY-FAK; Tyr397; 1:200; Millipore), mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:500; DM1A; Sigma), and they were incubated at 4°C overnight (16 h). After 3 PBS washes, appropriate secondary solutions were incubated for 1 h at ambient temperature: Hoescht 33342 (1:5000; Sigma), Alexa Fluor (488, 568, and 647) conjugated to α-rabbit and α-mouse IgG (1:1000), and Alexa Fluor-conjugated phalloidin (1:500; Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Images were captured at 12-bit depth on an Olympus IX-81 inverted microscope with a Fluoview-1000 confocal laser scanner and a ×60/1.42-NA oil-immersion objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), or a Zeiss Axiovert 200 LM equipped with an LSM 510 META and a ×40/1.3-NA oil-immersion objective (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Detector voltage, scan speed, pixel resolution, and laser power were standardized to ensure that images could be subjected to quantitative analyses. Images were exported as raw uncompressed TIF files and analyzed in ImageJ.

Live-cell imaging

To visualize the movement of MT+ ends in real time, cells were transfected with green fluorescent protein-tagged end-binding protein 1 (EB1-GFP) via ExGen (Fermentas, Burlington, ON, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 12-well plate to achieve 60% confluence the following day and then transfected with 1 μg of DNA combined with 3.3 μl of ExGen. The day after transfection, the cells were detached with trypsin, washed with PBS, seeded into a microchannel device, and allowed to migrate for 2 h before imaging with an Olympus IX-81 microscope equipped with a ×60/1.42-NA oil immersion objective lens and a FV-1000 confocal laser scanner. To visualize the rapid movement of EB1, 512- × 512-pixel images were scanned at 2 μs/pixel (0.5 s/frame); cells were imaged for 100 frames with no delay between acquisitions. Raw images were exported to ImageJ for analysis.

Statistical analysis

At least 3 independent trials were conducted for each experiment. One-tailed Student's t tests were used to compare average means. One-way ANOVA was used to compare variance between groups within a data set, and individual post hoc comparisons were performed via Tukey tests. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform statistical tests and generate all plots.

RESULTS

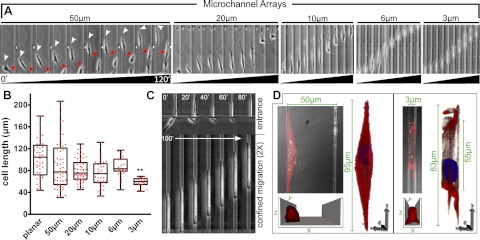

Physical properties of the ECM can regulate cell behavior (13–18); thus, we examined whether physical confinement could alter the migratory phenotype. We designed a migration chamber (12) that subjects cells to lateral (x) and vertical (z) confinement while permitting movement along the longitudinal (y) axis. The 4-walled microchannels were of variable width (3, 6, 10, 20, and 50 μm) with a fixed height (10 μm). This device enables the observation of cells in planar environments (outside the channels), nonconfining channels (50 and 20 μm), partial confinement (10 and 6 μm), and full confinement (3 μm) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Physical confinement alters the migratory phenotype. A) Time lapse of cells within each channel. Arrowheads indicate front (white) and rear (red) of a cell in a 50-μm channel. B) Contraction along the migratory axis in 50-μm channels results in variability in cell length that is suppressed as a function of decreasing channel width. Significance of difference between mean for planar and 3-μm groups was calculated via 1-way ANOVA and a post hoc Tukey test. **P < 0.001. C) Cell entering and migrating through a 3-μm channel is shown at 20-min intervals. D) Volumetric reconstructions of cells in 50-μm and 3-μm channels (red, F-actin; blue, Hoescht). Schematics at bottom depict orientation of the cell (channel ceiling not pictured).

Physical confinement induces cytoskeletal reorganization

Migrating MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were observed for up to 16 h and analyzed for morphological variability (Fig. 1A). Cells on planar regions and in 50-μm channels exhibit mesenchymal motion characterized by cyclic protrusion and retraction, which results in variable cell length. However, cell length becomes less variable as channel width decreases (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, cells in 3-μm channels exhibit nearly uniform cell length (Fig. 1C); this observation was verified in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SW1990) and HOS cells (data not shown). Cells in 50 μm channels assumed a variety of morphologies, including an elongated spindle shape when in contact with two channel surfaces (Fig. 1D). However, cytoskeletal features of 2D adhesion are present in these cells despite the morphological changes. Specifically, cortical F-actin is uniformly distributed and stress fibers are visible on either channel surface. In contrast, confinement induces a cuboidal morphology that lacks dorsoventral polarity and exhibits redistribution of F-actin to the cell poles and channel interfaces (Fig. 1D).

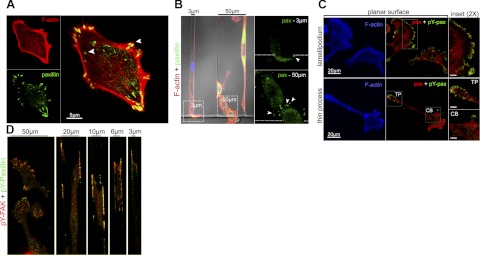

Physical confinement suppresses the formation of FAs

Because of the extensive actin remodeling in 3-μm channels, we predicted that substrate adhesions would also be modified by confinement. Cells produce FAs outside the channels (Fig. 2A), and no significant change in FA distribution is observed for cells in 50-μm channels (Fig. 2B). While some FAs form on the exterior 2D surface of the 3-μm channel entrance, no FAs are visible inside the 3-μm channels (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Confinement suppresses focal adhesions. A) Cell on a planar surface stained for paxillin (green) and F-actin (red). Arrowheads indicate FAs at the cell periphery and tips of stress fibers. B) Comparison of cells in contiguous 3-μm and 50-μm channels. Insets: magnified view of paxillin signal within boxed region at channel entrances (arrowheads indicate FAs; dotted line depicts threshold to channel entrance). C) Cells on planar surface stained for F-actin (blue), total paxillin (red), and pY-paxillin (green). Insets: magnified views of boxed regions for a broad membrane ruffle (top panel), thin protrusion (TP), and cell body (CB); scale bars = 5 μm. D) Representative images of cells within each channel type stained for pY-FAK (red) and pY-paxillin (green).

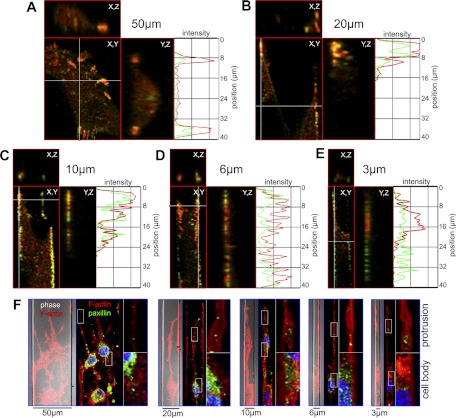

Tyrosine phosphorylation of FA proteins is associated with FA turnover and dynamic adhesions (19, 20). Accordingly, cells on planar surfaces exhibit tyrosine-phosphorylated paxillin (pY-paxillin) at the periphery of membrane protrusions (Fig. 2C). In light of the reduced presence of FAs in 3-μm channels, we examined the distribution of pY-paxillin and focal adhesion kinase (pY-FAK) as a function of channel width. Cells in 50-μm channels exhibit colocalization of pY-FAK and pY-paxillin, which is consistent with cells in 2D environments (21). In contrast, cells in channels ≤20 μm exhibit colocalization of pY-FAK and pY-paxillin at the lower channel interfaces (Figs. 2D and 3A–E). Orthogonal views reveal that pY-FAK and pY-paxillin are evenly distributed along the migratory axis as a function of increasing confinement (Fig. 3A–E, Y,Z subpanels). Specifically, cells confined in 3-μm channels contain smaller and more uniformly distributed adhesion sites in comparison with those in 50-μm channels (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

pY-FAK and pY-paxillin are evenly distributed along the migratory axis as a function of increasing confinement. A–E) Ventral (X,Y) and orthogonal (Y,Z; X,Z) views of pY-FAK (red) and pY-paxillin (green) for a 3D volume encompassing the leading edge of a cell for each channel type. Intensity profiles of lateral views (Y,Z) are plotted along the migratory axis for both pY-FAK and pY-paxillin (length 40 μm). F) ROCK inhibition blocks FA formation. Cells were treated with the p160ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (30 μM). Phase-contrast images (phase) overlaid with F-actin (red) show cell orientation and fluorescent panels depict paxillin (green). Insets: ×4 views of boxed regions showing protrusions (top) and cell body (bottom).

Migration in confinement does not require myosin-mediated contraction or β1-integrins

In light of the absence of large stress fibers in confinement, we wished to determine whether RhoA, a critical regulator of stress fibers and FAs (22, 23), exerts any control over migration in confinement. The Rho-associated kinase (p160ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 eliminates stress fibers and FAs (Fig. 3F). Y-27632 does not reduce the velocity of cells migrating in nonconfining channels but induces long-branching protrusions that cannot retract (Fig. 4A, E), thereby leading to a reduction in net cell displacement (Fig. 4F and Supplemental Movie S1). In contrast, Y-27632 does not suppress cell displacement in 3-μm channels nor directionality, but moderately increases the speed of migration (Fig. 4B, E, F and Supplemental Movie S1). To further examine the role of cell contraction, we used the specific inhibitor of myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) ML-7 (24). ML-7 abrogates locomotion in channels ≥6 μm but does not impair migration in 3-μm channels (Fig. 4C–E and Supplemental Movie S1). Because cell migration persists only in 3-μm channels when myosin is inhibited, we chose to restrict our attention to only planar environments and full confinement. Henceforth, we refer specifically to 3-μm channels when discussing confinement.

Figure 4.

Cell contractility is not required for confined migration. A) Cell in a 50-μm channel in the presence of 30 μM Y-27632. Thin protrusions at the leading edge (white arrowheads) underwent excessive branching (red arrowhead), and the trailing regions of the cell failed to contract (black arrowheads). Trajectories are shown for growing protrusions (branch) and overall cell displacement (trace). B) Cell in a 3-μm channel migrating in the presence of 30 μM Y-27632. Distance between the leading and trailing edges remained constant (white and black arrowheads, respectively); a trajectory depicts steady forward progress of the cell (trace). C) Cells in 50-μm channels in the presence of 20 μM ML-7 were relatively immobile (arrowheads). D) Cells migrated efficiently through 3-μm channels in the presence of ML-7. E) Cells migrating in the presence of the p160ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (20 μM) and the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 (30 μM) were compared; cell velocity is plotted as a percentage change relative to vehicle control. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001 vs. control; Student's t test. F) Average net displacement of cells treated with Y-27632 (20 μM), ML-7 (30 μM), or vehicle control over a period of 200 min. Values are means ± se.

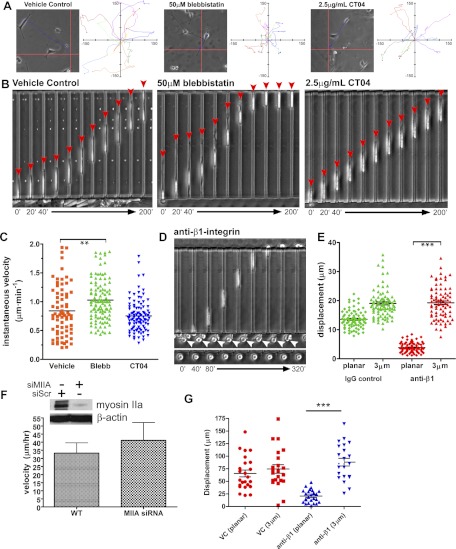

To verify the reduced role for myosin in confined migration, we inhibited myosin II with blebbistatin, which promotes its dissociation from F-actin (25), and used CT04: an inhibitor of RhoA, B, and C (26). Representative cell trajectories on planar ECM illustrate the effects of each treatment over 200 min (Fig. 5A). Blebbistatin reduces the length and persistence of planar cell trajectories relative to vehicle control, as does CT04, albeit to a lesser extent. In contrast, neither blebbistatin nor CT04 impairs migration in confinement (Fig. 5B). Although no reduction in instantaneous velocity is observed in the presence of CT04, blebbistatin actually enhances cell speed relative to vehicle control (Fig. 5C). Taken together, cellular contraction is not required for the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells through sufficiently confined space.

Figure 5.

Confinement suppresses the roles of contraction and integrins in migration. A) Representative trajectory for cells treated with vehicle control, 50 μM blebbistatin, and 2.5 μg/ml CT04 (grid origin denotes starting point). Ten trajectories are plotted for each condition (grid units: μm). B) Representative time-lapse images depicting migration through 3-μm channels (red arrows indicate cell front). C) Plot of instantaneous velocity for each condition. D) Treatment with a β1-integrin blocking antibody abolished migration outside the channels (bottom panel and bottom of top panel, arrowheads), but had no effect on migration through 3-μm channels (top panel). E) Average net displacement of cells with or without anti-β1 in planar regions and 3-μm channels. Values are means ± se. F) Pa03C pancreatic tumor cells were treated with siRNA targeting myosin IIA or a scramble control, as indicated by the Western blot depicting an immunoblot for myosin IIA. Migration velocities for both wild-type and siRNA-transfected cells are shown. G) Inhibiting integrins in Pa03C cells does not inhibit migration in confinement. Treatment with an anti-β1 integrin function-blocking antibody abolished cell movement outside the channels but had no effect on the net displacement through 3-μm channels. Three independent trials were performed. **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001; Student's t test.

In light of our data concerning focal adhesions and myosin in confined migration, we predicted that confinement attenuates the role of substrate adhesion. To remove the influence of ECM adhesion, cells were seeded in either uncoated or collagen-I-coated migration chambers in the presence of a function-blocking antibody for β1-integrin. As expected, anti-β1 treatment completely abolishes cell spreading and migration in planar regions; however, β1-integrin blockade has no effect on migration in confinement (Fig. 5D, E and Supplemental Movie S1). The inhibitory effects of anti-β1 treatment (in 2D environment) were retained for the duration of the experiment, as cells migrating in confinement arrested on exiting the 3-μm channels (Fig. 5D). These observations were verified with Pa03C pancreatic tumor cells (Fig. 5F, G), thereby revealing that physical confinement attenuates the dependence of migrating cells on integrin-mediated substrate adhesion.

Roles of actin and MT polymerization in confined migration

A recent computational study predicted that a cell constrained in a narrow channel will exhibit spontaneous motion that is driven by cytoskeletal polymerization and independent of substrate adhesion and contraction (27). The cytoskeleton is defined as a viscoelastic medium that behaves like a fluid in the cytoplasm and an elastic network at the cellular periphery where pressures are highest. Inward pressure displaces the cytoplasm in the direction of polymerization at the cell front, resulting in a continuous “flowing” motility. Our observations support these predictions in that cell shape, length, and instantaneous velocity remain constant during confined migration; the roles of integrins and myosin are suppressed by confinement; and the relative density of F-actin is reduced in the cell interior but elevated at the periphery in 3-μm channels (Fig. 1D).

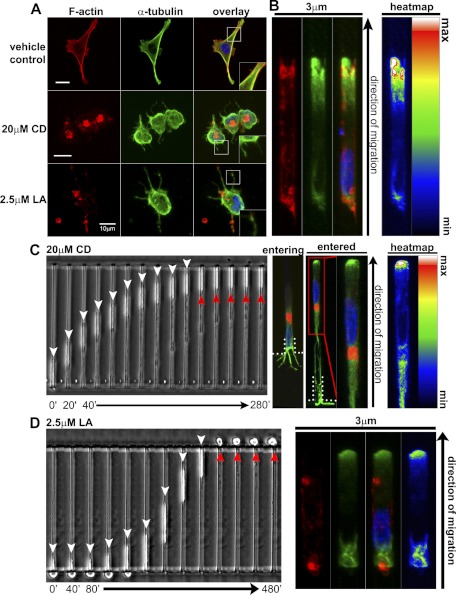

To determine whether actin polymerization drives migration in confinement, cells were seeded at microchannel entrances in the presence of the actin polymerization inhibitor CD (28). CD disrupts F-actin and promotes the protrusion of MTs from the cell periphery (Fig. 6A, 20 μM CD), which occur on release of cortical actin tension (29, 30). In confinement, control cells exhibit α-tubulin polarization at the cell front (Fig. 6B). As expected, CD abrogates migration in 2D environments, but, surprisingly, cells seeded at 3-μm channel entrances still protrude into the channels, and a significant fraction are able to migrate through (Fig. 6C). CD-treated cells migrating in 3-μm channels exhibit perinuclear F-actin aggregates and enrichment of α-tubulin at the cell front (Fig. 6C, right panels). This finding demonstrates that, even without F-actin, cells can migrate in confinement where α-tubulin localizes to the leading edge.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of actin polymerization does not block migration in confinement. A) F-actin and α-tubulin after treatment with vehicle control, CD, or LA. MT protrusions formed in CD- and LA-treated cells. F-actin aggregates are also visible, but less prominent in LA-treated cells. Insets: ×2 views of boxed regions. B) Vehicle control cell migrating in a 3-μm channel. Intensity map depicts polarization of α-tubulin toward the cell front. C) Time-lapse image of a CD-treated cell entering a 3-μm channel (white arrowheads), but unable to exit (red arrowheads). Immunofluorescence analysis confirms F-actin disruption inside the channel and demonstrates the polarization of α-tubulin at the cell front in a CD-treated cell. D) LA-treated cell migrating through a 3-μm channel (red arrowhead indicates failure to spread and migrate on exiting the channel). Immunofluorescence confirmed the disruption of F-actin and polarity of α-tubulin.

To verify this unexpected result, we used LA, a potent inhibitor of actin polymerization (31). LA reduces F-actin aggregates and abolishes migration in 2D environments. However, cells in contact with 3-μm channel openings still migrate through them (Fig. 6A, D and Supplemental Movie S2). Migration ceases abruptly when cells exit confinement, confirming that the depolymerizing effects of LA persist for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 6D, red arrowheads); this was also verified via immunofluorescence (Fig. 6D, right panel). As with CD, α-tubulin in LA-treated cells is enriched at the cell front in confinement.

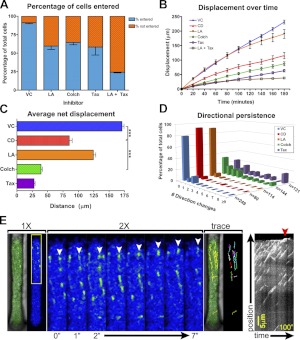

To determine whether MTs contribute to migration in confinement, we compared the effects of actin inhibitors to paclitaxel (Taxol), which prevents MT depolymerization, and colchicine, which promotes MT disassembly (32–34). Both MT and actin inhibitors impair the ability of cells to enter the channels, and this inhibition is enhanced by combinatorial treatment (Fig. 7A). However, colchicine and Taxol inhibit velocity and overall displacement more severely relative to actin inhibitors (Fig. 7B, C). Furthermore, MT inhibition reduces the directionality of migration relative to vehicle control and actin inhibitors (Fig. 7D and Supplemental Movie S3). Collectively, these results suggest that both actin and MTs regulate the entry into confined space but that MTs regulate the speed and direction of movement in confinement.

Figure 7.

Confinement promotes the role of MTs in migration. A) Percentage of cells that entered 3-μm channels is plotted as fraction of the total population analyzed. Drugs used were vehicle control (VC), 20 μM CD, 2.5 μM LA, 125 μM colchicine (Colch), and 1.2 μM Taxol (Tax). B) Cell displacement in the presence of each drug is plotted as mean ± se as a function of time. C) Average net displacement of cells over a period of 200 min, plotted for each inhibitor; 3 independent trials. ***P < 0.0001; Student's t test. D) Directional persistence of cells migrating in 3-μm channels, depicted as the fraction of cells that executed a defined number of direction changes over the course of 16 h. Number of cells analyzed (n) is indicated on the z axis. E) EB1-GFP revealed that nascent MT growth was polarized in the direction of the cell front (top of panel). Individual EB1 particles were tracked until they disappeared or impacted the leading edge (white arrowheads depict movement over a period of 7 s; an intensity color filter was applied to improve clarity of individual particles). EB1 motion is depicted with a particle trace. Kymograph depicts the gradual advancement of the cell membrane concomitant with EB1 impact (right panel, red arrowhead).

MTs emanate from the MT organizing center (MTOC) and grow toward the plasma membrane, where they buckle in response to mechanical resistance in the cell cortex (35). Because of high cortical actin tension, the plasma membrane normally resists MT-mediated deformation. However, MT stabilization via MT-associated proteins or post-translational modification enables MTs to overcome cortical resistance and protrude the plasma membrane (30, 36). Alternatively, relaxation of cortical actin tension facilitates MT-mediated protrusion of the plasma membrane (Supplemental Movie S4 and ref. 37). To determine how confinement influences patterns of MT growth, EB1-GFP was used to visualize MT+ ends. MTs polymerize from the MTOC in all directions in 2D environments (Supplemental Movie S4, arrowhead). However, nascent MTs polymerize largely toward the leading edge in confinement (Fig. 7E and Supplemental Movie S4). Nascent MTs concentrate near the cell front, corroborating the observation that α-tubulin concentrates at the leading edge in confinement. MTs deflect off of the channel walls and are redirected toward the cell front; a kymographic analysis illustrates the continuous impact of growing MTs at the leading edge, concomitant with advancement of the membrane (Fig. 7E, red arrow). Collectively, these results demonstrate that physical confinement promotes cytoskeletal reorganization that attenuates the role of force coupling and facilitates an increased role for MTs in cell migration.

DISCUSSION

Many 2D adhesion and migration phenotypes are suppressed in 3D environments (3, 8, 9). For example, leukocytes and tumor cells can utilize integrin-independent mechanisms to navigate 3D environments (6, 7, 11). To determine whether a physical stimulus could underlie this transition, we isolated the effects of confinement using a microchannel device. Microchannel models have been used to examine the invasive capacity of various cell types (38, 39). While another study described a similar “sliding” motility, the underlying mechanism was not determined (40). Here, we demonstrate that confinement alone is sufficient to modify the migratory phenotype. In support of this idea are other studies that utilized agarose gel assays (42) or 2-photon laser-generated microtracks in collagen gels (43) to physically confine cells. Furthermore, a prior study reported that integrin-blocked polymorphonuclear leukocytes regain the ability to migrate when vertically compressed between two glass surfaces; however, the mechanistic relationship between physical compression and the onset of integrin-independent motility was not explored (41). Here, we build on these reports by further exploring the mechanistic nature of cell migration in confined spaces.

In examining the effects of physical constraint on cell migration, we conclude that confinement induces cytoskeletal restructuring that suppresses the mesenchymal phenotype. Specifically, F-actin concentrates at the cell periphery (i.e., in channel corners) where only small tyrosine-phosphorylated substrate adhesions form. Because cytoskeletal tension is known to regulate the formation and maturation of focal complexes into FAs (44), the uniform distribution of these small adhesions may be due to the uniformity in actin tension along the migratory axis. Therefore, by altering the structure of (and tension in) the actin cytoskeleton, confinement precludes the development of mature FAs. Indeed, a lack of FAs has been reported for cells fully immersed in collagen gels and floating matrices (8, 9). However, Fraley et al. (8) found that FAs did begin to appear as the collagen-embedded cells neared the rigid glass to which the gel was attached. Therefore, given the influence of cellular tension on substrate adhesions and the physical heterogeneity of physiological environments, it may be oversimplistic to conclude whether FAs do (or do not) form in vivo. Instead, it is more accurate to envision substrate adhesions as dynamic structures that manifest in various forms as dictated by the physical properties of a given environment.

All cell types migrating in confinement exhibited consistent displacement and cell length. Furthermore, migration in confinement does not depend on myosin. Although myosin II is required for mesenchymal and amoeboid motility (6), it has also been shown that migration persists in confinement without functional myosin (38). Here, we verify that ideal confinement (i.e., consistent geometry and continuous, unobstructed space) facilitates contraction-independent movement. This constitutes proof-of-principle evidence that the extent to which a cell migrating in 3D space depends on contraction is influenced by the physical constriction it experiences. Because physiological 3D environments are not ideal (i.e., discontinuous), contraction is not dispensable for migration in vivo; however, it may be that both the function and extent of involvement for contraction are regulated by the structural properties of the environment. For example, MDA-MB-231 cells utilize contraction of a peripheral actomyosin network to navigate discontinuous 3D environments (5), which reinforces the notion that myosin regulates movement in 2D and 3D environments via different mechanisms. Thus, it is possible that, by redistributing F-actin to the cell periphery, physical confinement may actually facilitate a transition to the amoeboid phenotype. This transition to a nonpolar morphology would also preclude the formation of FAs and adhesion-contraction force coupling, which could account for a reduced or altered role for integrins in 3D environments.

Our data suggest that cytoskeletal polymerization drives migration in confinement. Surprisingly, we observed that MTs play a major role in regulating both cell speed and directionality. We observed that physical confinement regulates MT polarity by deflecting and redirecting growing MTs toward the cell front. Cytoskeletal redirection along a path of least resistance could enable cells to passively locate preexisting gaps in the ECM (11). Though the forces of individual MTs impacting the plasma membrane are negligible, these events occur continuously and could cumulatively provide sufficient force to incrementally advance the cell front. This seems plausible when one considers that confinement induces cortical actin restructuring, which allows MTs to deform and protrude the plasma membrane (45).

Inhibiting the polymerization of both actin and MTs reduces the efficiency with which cells enter confined environments. However, disruption of actin does not inhibit migration once the cells are inside the channel; in line with this observation, neurons are able to extend neurites after inhibition of actin (46). In comparison with actin inhibition, MT inhibition is significantly more effective at disrupting migration inside 3-μm channels. Accordingly, the combination of LA and Taxol completely blocks migration by 1 h, though some cells did enter the channels (which likely resulted from initial MT polymerization that ceased when the pool of soluble tubulin was exhausted). Such a prominent role for MTs in confined migration raises intriguing possibilities regarding the use of MT-targeted chemotherapies. It is conceivable that adjuvant Taxol therapies, which can suppress locoregional recurrence when administered after primary resection (47), do so by inhibiting the invasive properties of occult tumor cells. Furthermore, mechanical pliability regulates the invasion of tumor cells (40, 48); thus, Taxol could impede movement through ECM gaps by decreasing cellular deformability. Similarly, ROCK inhibition and blebbistatin attenuate cellular tension by inhibiting contractility, which may explain why these treatments actually enhance the rate of migration in confinement.

CONCLUSIONS

We find that physical confinement modifies cytoskeletal structure, and thereby suppresses cellular dependence on tractive “pulling” forces transduced through “focalized” substrate adhesions. By promoting uniform cytoskeletal tension and distribution of substrate adhesions, physical constraints suppress conventional 2D phenotypes of adhesion and migration. This biophysical mechanism could explain the observed discrepancies between the roles of substrate adhesions in 2D and 3D environments. While integrin-mediated adhesion and cellular contraction are not required for migration in ideal confinement, these processes may simply be suppressed or altered by the extent of physical constriction imposed within 3D environments in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (awards T32-CA130840, U54-CA143868, and RO1-CA101135) and the Kleberg Foundation.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 2D

- 2-dimensional

- 3D

- 3-dimensional

- CD

- cytochalasin D

- EB1-GFP

- green fluorescent protein-tagged end-binding protein 1

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FA

- focal adhesion

- HOS

- human osteosarcoma

- LA

- latrunculin-A

- MLCK

- myosin light-chain kinase

- MT

- microtubule

- MTOC

- microtubule organizing center

- PDMS

- polydimethylsiloxane

- pY-FAK

- tyrosine-phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase

- pY-paxillin

- tyrosine-phosphorylated paxillin

- ROCK

- Rho-associated kinase

REFERENCES

- 1. Gardel M. L., Schneider I. C., Aratyn-Schaus Y., Waterman C. M. (2010) Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 315–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Even-Ram S., Yamada K. M. (2005) Cell migration in 3D matrix. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beningo K. A., Dembo M., Wang Y. L. (2004) Responses of fibroblasts to anchorage of dorsal extracellular matrix receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 18024–18029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lakshman N., Kim A., Bayless K. J., Davis G. E., Petroll W. M. (2007) Rho plays a central role in regulating local cell-matrix mechanical interactions in 3D culture. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 64, 434–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poincloux R., Collin O., Lizarraga F., Romao M., Debray M., Piel M., Chavrier P. (2011) Contractility of the cell rear drives invasion of breast tumor cells in 3D matrigel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 1943–1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lammermann T., Bader B. L., Monkley S. J., Worbs T., Wedlich-Soldner R., Hirsch K., Keller M., Forster R., Critchley D. R., Fassler R., Sixt M. (2008) Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature 453, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friedl P., Entschladen F., Conrad C., Niggemann B., Zanker K. S. (1998) CD4+ T lymphocytes migrating in three-dimensional collagen lattices lack focal adhesions and utilize β1 integrin-independent strategies for polarization, interaction with collagen fibers and locomotion. Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 2331–2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fraley S. I., Feng Y., Krishnamurthy R., Kim D. H., Celedon A., Longmore G. D., Wirtz D. (2010) A distinctive role for focal adhesion proteins in three-dimensional cell motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 598–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wozniak M. A., Desai R., Solski P. A., Der C. J., Keely P. J. (2003) ROCK-generated contractility regulates breast epithelial cell differentiation in response to the physical properties of a three-dimensional collagen matrix. J. Cell Biol. 163, 583–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cukierman E., Pankov R., Stevens D. R., Yamada K. M. (2001) Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science 294, 1708–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolf K., Mazo I., Leung H., Engelke K., von Andrian U. H., Deryugina E. I., Strongin A. Y., Brocker E. B., Friedl P. (2003) Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J. Cell Biol. 160, 267–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tong Z. Q., Balzer E. M., Dallas M. R., Hung W. C., Stebe K. J., Konstantopoulos K. (2012) Chemotaxis of cell populations through confined spaces at single-cell resolution. Plos One 7 e29211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ehrbar M., Sala A., Lienemann P., Ranga A., Mosiewicz K., Bittermann A., Rizzi S. C., Weber F. E., Lutolf M. P. (2011) Elucidating the role of matrix stiffness in 3D cell migration and remodeling. Biophys. J. 100, 284–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaalouk D. E., Lammerding J. (2009) Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Discher D. E., Janmey P., Wang Y. L. (2005) Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science 310, 1139–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paszek M. J., Zahir N., Johnson K. R., Lakins J. N., Rozenberg G. I., Gefen A., Reinhart-King C. A., Margulies S. S., Dembo M., Boettiger D., Hammer D. A., Weaver V. M. (2005) Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 8, 241–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stroka K. M., Aranda-Espinoza H. (2009) Neutrophils display biphasic relationship between migration and substrate stiffness. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 328–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stroka K. M., Aranda-Espinoza H. (2011) Endothelial cell substrate stiffness influences neutrophil transmigration via myosin light chain kinase-dependent cell contraction. Blood 118, 1632–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nayal A., Webb D. J., Brown C. M., Schaefer E. M., Vicente-Manzanares M., Horwitz A. R. (2006) Paxillin phosphorylation at Ser273 localizes a GIT1-PIX-PAK complex and regulates adhesion and protrusion dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 173, 587–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zaidel-Bar R., Milo R., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2007) A paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation switch regulates the assembly and form of cell-matrix adhesions. J. Cell Sci. 120, 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zamir E., Katz M., Posen Y., Erez N., Yamada K. M., Katz B. Z., Lin S., Lin D. C., Bershadsky A., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2000) Dynamics and segregation of cell-matrix adhesions in cultured fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gupton S. L., Waterman-Storer C. M. (2006) Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell 125, 1361–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hotulainen P., Lappalainen P. (2006) Stress fibers are generated by two distinct actin assembly mechanisms in motile cells. J. Cell Biol. 173, 383–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katoh K., Kano Y., Amano M., Kaibuchi K., Fujiwara K. (2001) Stress fiber organization regulated by MLCK and Rho-kinase in cultured human fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C1669–C1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kovacs M., Toth J., Hetenyi C., Malnasi-Csizmadia A., Sellers J. R. (2004) Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35557–35563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benink H. A., Bement W. M. (2005) Concentric zones of active RhoA and Cdc42 around single cell wounds. J. Cell Biol. 168, 429–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hawkins R. J., Piel M., Faure-Andre G., Lennon-Dumenil A. M., Joanny J. F., Prost J., Voituriez R. (2009) Pushing off the walls: a mechanism of cell motility in confinement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 058103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goddette D. W., Frieden C. (1986) Actin polymerization. The mechanism of action of cytochalasin D. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 15974–15980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balzer E. M., Whipple R. A., Thompson K. T., Boggs A. E., Slovic J., Cho E. H., Matrone M. A., Yoneda T., Mueller S. C., Martin S. S. (2010) c-Src differentially regulates the functions of microtentacles and invadopodia. Oncogene 29, 6402–6408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Whipple R. A., Balzer E. M., Cho E. H., Matrone M. A., Yoon J. R., Martin S. S. (2008) Vimentin filaments support extension of tubulin-based microtentacles in detached breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 68, 5678–5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spector I., Shochet N. R., Kashman Y., Groweiss A. (1983) Latrunculins: novel marine toxins that disrupt microfilament organization in cultured cells. Science 219, 493–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yvon A. M., Wadsworth P., Jordan M. A. (1999) Taxol suppresses dynamics of individual microtubules in living human tumor cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 947–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Waterman-Storer C. M., Salmon E. D. (1997) Microtubule dynamics: treadmilling comes around again. Curr. Biol. 7, R369–R372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jordan M. A., Wilson L. (2004) Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Janmey P. A., Euteneuer U., Traub P., Schliwa M. (1991) Viscoelastic properties of vimentin compared with other filamentous biopolymer networks. J. Cell Biol. 113, 155–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matrone M. A., Whipple R. A., Thompson K., Cho E. H., Vitolo M. I., Balzer E. M., Yoon J. R., Ioffe O. B., Tuttle K. C., Tan M., Martin S. S. (2010) Metastatic breast tumors express increased tau, which promotes microtentacle formation and the reattachment of detached breast tumor cells. Oncogene 29, 3217–3227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Balzer E. M., Whipple R. A., Cho E. H., Matrone M. A., Martin S. S. (2010) Antimitotic chemotherapeutics promote adhesive responses in detached and circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 121, 65–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Faure-Andre G., Vargas P., Yuseff M. I., Heuze M., Diaz J., Lankar D., Steri V., Manry J., Hugues S., Vascotto F., Boulanger J., Raposo G., Bono M. R., Rosemblatt M., Piel M., Lennon-Dumenil A. M. (2008) Regulation of dendritic cell migration by CD74, the MHC class II-associated invariant chain. Science 322, 1705–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Irimia D., Toner M. (2009) Spontaneous migration of cancer cells under conditions of mechanical confinement. Integr. Biol. (Camb.) 1, 506–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rolli C. G., Seufferlein T., Kemkemer R., Spatz J. P. (2010) Impact of tumor cell cytoskeleton organization on invasiveness and migration: a microchannel-based approach. PLoS One 5, e8726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malawista S. E., de Boisfleury Chevance A. (1997) Random locomotion and chemotaxis of human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) in the presence of EDTA: PMN in close quarters require neither leukocyte integrins nor external divalent cations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 11577–11582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Renkawitz J., Schumann K., Weber M., Lammermann T., Pflicke H., Piel M., Polleux J., Spatz J. P., Sixt M. (2009) Adaptive force transmission in amoeboid cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1438–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ilina O., Bakker G. J., Vasaturo A., Hofmann R. M., Friedl P. (2011) Two-photon laser-generated microtracks in 3D collagen lattices: principles of MMP-dependent and -independent collective cancer cell invasion. Phys. Biol. 8, 015010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galbraith C. G., Yamada K. M., Sheetz M. P. (2002) The relationship between force and focal complex development. J. Cell Biol. 159, 695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matrone M. A., Whipple R. A., Balzer E. M., Martin S. S. (2010) Microtentacles tip the balance of cytoskeletal forces in circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 70, 7737–7741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bradke F., Dotti C. G. (1999) The role of local actin instability in axon formation. Science 283, 1931–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu R., Wolinsky J. B., Catalano P. J., Chirieac L. R., Wagner A. J., Grinstaff M. W., Colson Y. L., Raut C. P. (2011) Paclitaxel-eluting polymer film reduces locoregional recurrence and improves survival in a recurrent sarcoma model: a novel investigational therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guck J., Schinkinger S., Lincoln B., Wottawah F., Ebert S., Romeyke M., Lenz D., Erickson H. M., Ananthakrishnan R., Mitchell D., Kas J., Ulvick S., Bilby C. (2005) Optical deformability as an inherent cell marker for testing malignant transformation and metastatic competence. Biophys. J. 88, 3689–3698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.