Abstract

With the advent of genetic engineering, zebrafish (Danio rerio) were recognized as an attractive model organism to study many biological processes. Remarkably, the small size and optical transparency of zebrafish larvae enable high-resolution imaging of live animals. Zebrafish respond to various environmental and pathological factors with robust oxidative stress. In this article, we provide an overview of molecular mechanisms involved in oxidative stress and antioxidant response in zebrafish. Existing applications of generically-encoded fluorescent sensors allow imaging, in real time, production of H2O2 and studying its involvement in inflammatory responses, as well as activation of oxidation-sensitive transcription factors HIF and NRF2. Oxidative stress, combined with hypelipidemia, leads to oxidation of lipoproteins, the process that contributes significantly to development of human atherosclerosis. Recent work found that feeding zebrafish a high-cholesterol diet results in hypercholesterolemia, vascular lipid accumulation and extreme lipoprotein oxidation. Generation of a transgenic zebrafish expressing a GFP-tagged human antibody to malondialdehyde (MDA)-modified LDL makes possible in vivo visualization of MDA epitopes in the vascular wall and testing the efficacy of antioxidants and dietary interventions. Thus, using zebrafish as a model organism provides important advantages in studying the role of ROS and lipid oxidation in basic biologic and pathologic processes.

Introduction

Applications of zebrafish models become increasingly popular in various fields of biomedical research and drug development. Traditionally, many toxicological studies have been using zebrafish embryos and larvae for initial characterization of environmental hazards or therapeutic candidates, before advancing to larger animal models. Small size, multiple progeny from a single mating, the straightforward route of chemicals administration, especially for water-soluble compounds, are among the advantages of using zebrafish for the survival/lethality type of experiments. Recent studies have introduced more advanced read-out assays, such as assessing neuronal and liver damage, renal dysfunction, gene expression analysis, DNA damage and fluorescence-based reporter assays [1].

For the reasons that will be discussed in this article, zebrafish respond to many pathological factors with robust oxidative stress. Thus, measuring parameters of oxidative stress is one of the most common categories of assays used in zebrafish toxicological studies [2–4]. The oxidative stress assays were also applied to test detrimental effects of administering oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) and pro-survival effects of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), including specific mutants of the HDL protein APO-AI that enhance its function [5,6].

In addition to the toxic effects of high doses of ROS, intracellular production of ROS is intimately involved in regulation of normal cellular function and in inflammatory responses [7,8]. Inflammation is now recognized as a major factor in pathogenesis of many chronic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, the metabolic syndrome and diabetes [9–12]. We will discuss recent work demonstrating the advantages of zebrafish as an animal model to elucidate the connection between oxidative mechanisms and inflammatory processes relevant to early stages in development of these chronic conditions. We will describe chemical probes used to measure specific ROS in zebrafish and the latest advances in applications of transgenic zebrafish, which express genetically-encoded sensors for ROS, oxidation-regulated transcription factors and oxidized lipids. We will conclude with the discussion of future directions for mechanistic studies as well as for testing novel therapeutic approaches that would aim to regulate oxidative processes involved in pathogenesis of human disease.

Zebrafish as a model organism

General characteristics

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are small, fresh water, teleost fish. Adult zebrafish are 30–40 mm long and weigh 300–500 mg. They reach fertile age by 3 months and live for up to 2 years under laboratory conditions (water at 28.5°C, 14/10 hours light/dark cycle). Female lay up to 200 eggs per mating and male fertilize the eggs with sperm ex vivo. Following fertilization, embryos develop in a chorion and then hatch approximately 48 hours post fertilization (hpf). Embryos can be mechanically dechorionated for experimental work at any time. By the 5–6th day post fertilization (dpf) zebrafish larvae consume the yolk nutrients and begin free feeding. Maintenance of zebrafish is relatively inexpensive and large numbers of animals can be produced for each experiment.

Among the major advantages of using zebrafish is the optical transparency of embryos and larvae for up to 30 dpf. They are small and thin enough to be imaged with a confocal microscope at high resolution (63× objective). Embryos can be immobilized to capture time lapse images for several days and older larvae can be anesthetized and remain immobile for up to 20 minutes, the time sufficient to capture high quality optical z-sections, and the imaging sessions can be repeated several times.

Since efficient methods to manipulate zebrafish gene expression have been developed and because zebrafish larvae are transparent, numerous transgenic animals expressing fluorescent proteins in various cell types and tissues have been generated. Stable transgenic zebrafish lines expressing EGFP, DsRed, mCherry and other fluorescent proteins in endothelial cells, neutrophils, macrophages, skeletal muscle and other cell types can be obtained from investigators who develop them and from Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC; http://zebrafish.org). ZIRC also maintains a large collection of zebrafish mutants in which the phenotype has been described and the genetic mutation defined. Zebrafish knockout technology has also been reported [13,14]. There are no yet embryonic stem cells isolated from zebrafish and, thus, current gene knockout techniques used in mice cannot be applied to zebrafish. However, an alternative method using zinc finger nuclease mediated site-specific DNA double strand breaks is now used to produce knockout zebrafish [15,16]. A newly developed method of transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN)-mediated gene knockout [17,18] has spurred the great interest in the zebrafish research community. The zebrafish genome has been completely sequenced (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/). Comparison of the genome sequences reveals highly conserved genes involved in oxidation, lipid metabolism and inflammation, and many of the corresponding zebrafish proteins have been demonstrated to function in the same way as their mammalian homologs [19–33].

The characteristics of the zebrafish model listed above and its many other features that we have not mentioned to keep this article focused, make zebrafish an attractive model organism to study oxidative mechanisms and their role in pathogenesis of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. In particular, using the advantage of in vivo high resolution imaging enables direct monitoring of physiologic and pathologic processes in live animals.

Oxygen- and electrophile-responsive transcription and enzymatic antioxidant systems

Many of the oxidation-sensitive transcription factors are conserved in zebrafish. Zebrafish express the critical components of the oxygen-sensing signaling system, including hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL), and several isoforms of prolyl hydroxylase (PHD). At normal oxygen tension in tissues, PHD specifically hydroxylates HIFα, which triggers pVHL binding to HIFα, followed by HIFα ubiquitination and degradation. However, under hypoxic conditions, HIFα escapes hydroxylation and degradation and translocates to the nucleus where it associates with HIFβ and initiates a diverse transcription program aimed to alleviate the detrimental effects of hypoxia [34]. Since the hypoxia inflicted damage in large part is due to overproduction of free radicals, HIF targets include heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), an enzyme important in cellular defense against oxidative stress [35]. Because systemic hypoxia accompanies human pulmonary dysfunction and local hypoxia is a characteristics of atherosclerotic lesions and rapidly proliferating tumors, elucidating HIF-dependent mechanisms is of particular importance for understanding and treatment of human disease.

Recent studies have demonstrated that vhl zebrafish mutants display systemic hypoxic response, characterized by hyperventilation, cardiomegaly and elevated cardiac output, and severe polycythemia [36]. The gene expression profile of vhl mutants shows enrichment in genes related to the anaerobic metabolism, oxygen sensing and transport, angiogenesis, and hematopoietic proliferation. The vhl zebrafish mutants are also predisposed to carcinogen-induced hepatic and intestinal tumors [37], supporting the role of HIF in regulation of tumorigenesis. Maeda and coworkers have found that zebrafish Cullin-2 (Cul2), the protein involved in pVHL-mediated ubiquitination of HIFα, is required for normal vasculogenesis, the effect at least in part mediated by Cul2 regulation of Hif-mediated expression of Vegf and Flk [38]. Using a pharmacologic inhibitor of PHD enzymes and dominant-negative and dominant-positive variants of zebrafish Hifα, Elks et al. have shown that Phd-dependent hydroxylation of Hifα is critical for timely resolution of neutrophilic inflammation [39]. Stabilization of Hif resulted both in reduced neutrophil apoptosis and in increased retention of neutrophils at the site of a tail fin wound.

Zebrafish have also been used to study nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a transcription factor that plays an important role in the regulation of antioxidant gene expression via its interaction with antioxidant/electrophile response elements (ARE/EPRE). Similarly to HIFα, under normal redox conditions, NRF2 is associated with a repressor protein, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein (KEAP1), which targets NRF2 for ubiquitination. KEAP1 contains redox-sensitive cysteines, which undergo oxidation if the balance shifts toward electrophiles, leading to release of NRF2 and its translocation to the nucleus and activation of ARE-regulated genes [40].

Zebrafish nrf2a and nrf2b are the two homologs of human NRF2, which have different distribution and expression levels in the zebrafish embryo [41]. On the functional level, zebrafish Nrf2a plays a similar protective function as its mammalian NRF2 ortholog, while Nrf2b negatively regulates expression of antioxidative genes [41]. As in mammals, zebrafish Nrf2a activates expression of enzymes involved in de novo glutathione (GSH) biosynthesis, such as 3-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γGsh), as well as glutathione-S-transferase (Gst), which recycles oxidized glutathione (GSSG), and a detoxifying enzyme NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (Nqo1) [30].

The second pathway of regulation of these antioxidant enzymes is via aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), which is activated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and binds to xenobiotic response elements (XREs). In addition to various gst and nqo genes, the AHR/XRE axis regulates enzymes of the cytochrome P450 (cyp1) family, glutathione peroxidase 1 (gpx1), and the glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (gclc) [33]. The expression of Mn- and Cu, Zn-dependent superoxide dismutases (Sod) and catalase (Cat), the enzymes that reduce superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide, is well documented in zebrafish [33,42–44]. The expression levels of these enzymes are markedly increased in zebrafish exposed to pollutants and drugs [42,45].

Lipid metabolism

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and PUFA-containing phospholipids (PL) and cholesterol esters (CE) are highly susceptible to oxidation, yielding a variety of lipid free radicals, peroxides, epoxides, endoperoxides, aldehydes, and ketones, many of which in turn modify other lipids, sterols, proteins and nucleic acids. In humans, hyperlipidemia often leads to increased lipid oxidation, and oxidation of LDL is considered a leading pathogenic factor in development of atherosclerosis [46–48].

Lipid metabolism in zebrafish, and in teleost fish in general, is surprisingly similar to that in humans. Moreover, fish preferentially use lipids rather than carbohydrates as an energy source and would be classified, using standards applied to mammals, as hyperlipidemic and hypercholesterolemic [49,50]. Analytical ultracentrifugation identified VLDL, LDL and HDL lipoprotein classes in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), with HDL dominating the lipoprotein profile [50]. Native agarose gel electrophoresis of normal zebrafish plasma shows mostly the HDL fraction as well; however, the lipoprotein profile of zebrafish fed a high-cholesterol diet (HCD) is identical to that of human plasma, with LDL and VLDL found at higher proportions than HDL [51]. The nature and the distribution of apolipoproteins in different classes of fish lipoproteins resembles that in mammals, but plasma concentration of apolipoproteins in rainbow trout accounts for 36% of total protein, compared with only 10% in humans [50]. Antibodies against human APOB-100 and APOA-I recognize proteins of a similar molecular mass in zebrafish plasma [51]. During embryonic fish development, yolk syncytial layer actively synthesizes Apoe and other apolipoproteins and forms VLDL from yolk lipids, which then enter the circulatory system and deliver nutrient lipids to the tissues [20,52]. As in humans, zebrafish microsomal triglyceride transfer ptrotein (Mtp) is involved in the VLDL assembly in the yolk and, later, in the intestinal lipoprotein synthesis [26,53]. Lipoprotein lipase, hepatic lipase and lecitin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) activities have been shown in several fish species, and there is evidence suggesting the presence of cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) activity in rainbow trout plasma [50]. Zebrafish express cetp, homologous to human CETP, and Cetp activity in zebrafish plasma increases with hypercholesterolemia, reaching the levels comparable to that in humans [54,55]. In fact, measuring Cetp activity is an important advantage of the zebrafish model compared to studies with mice who do not express CETP. CETP is considered an important therapeutic target for human dyslipidemia.

Studies of intestinal lipid metabolism in zebrafish have identified annexin2-caveolin1 and fat-free as important factors in cholesterol absorption and the targets for anti-hyperlipidemic therapies [27,56]. Zebrafish also express npc1l1, an ortholog of the human NPC1L1 gene encoding intestinal Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1. NPC1L1 is involved in intestinal absorption and transfer of cholesterol and is a target of ezetimibe, an important cholesterol-lowering drug. The ezetimibe-binding domain in zebrafish Npc1l1 is highly homologues to the corresponding domain in human NPC1L1, with the preserved phenylalanine and methionine residues required for high-affinity binding of ezetimibe [57]. Larvae treated with ezetimibe shows 25–75% reductions in intestinal fluorescence derived from NBD-cholesterol [57]. These data suggest that the mechanism of inhibition of intestinal cholesterol absorption by ezetimibe in zebrafish is similar to that in humans, but direct evidence of the involvement of Npc1l1 in zebrafish cholesterol metabolism targeted by ezetimibe has not yet been reported. We found that ezetimibe was very effective in reducing total cholesterol levels in HCD-fed zebrafish larvae. Already at the concentration of 1 μM, ezetimibe reduced cholesterol to the levels observed in larvae fed control diet. In contrast, simvastatin, the drug targeting HMG-CoA reductase, was less effective in reducing cholesterol levels in zebrafish [58].

The reports summarized in this section demonstrate that redox signaling, antioxidant enzymes and lipid metabolism, the areas of importance to researchers interested in oxidative mechanisms and their role human disease, are strikingly similar in humans and in zebrafish. Combined with the advantages of using zebrafish as a model organism, these similarities enable in vivo studies of specific physiologic and pathologic mechanisms that would be impossible or difficult to conduct with other animal models.

In vivo imaging of ROS and oxidation-dependent signaling

Chemical probes

Because zebrafish larvae are optically transparent, they can be used to monitor ROS in vivo. A number of fluorescent probes have been adapted for use in zebrafish experiments. The common fluorogenic dye 2′,7′-dihydrodichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), which is oxidized by ROS to produce green fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF), was used in zebrafish embryos to demonstrate ROS production in response to PMA [59]. The same probe was used in a high-throughput assay in which ROS, produced in response to hydrogen peroxide, arsenic trioxide, and phenethyl isothiocyanate, was quantified in zebrafish larvae. The ROS response was inhibited in the presence of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine [60]. Although H2DCFDA has low selectivity for various oxidants, it is a good general sensor of ROS.

During inflammation, hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is produced by myeloperoxidase (MPO)-mediated peroxidation of chloride ions in activated neutrophils and macrophages. HOCl contributes to the destruction of bacteria in living organisms as well as to modification of lipoproteins during atherogenesis. A large number of probes have been synthesized to detect MPO activity and HOCl [61–65]. For example, the water-soluble dihydrofluorescein-ether probe FCN2 was demonstrated to detect micromolar concentrations of HOCl both in vitro and in vivo in zebrafish [66]. A rhodamine-hydroxamic acid-based fluorescent probe for HOCl was used in similar applications [64]. However, in these experiments, HOCl was added to water rather than produced in zebrafish in response to e.g. a bacterial challenge. Thus, fluorescent HOCl probes are suitable for toxicologic studies, but their use for biologic experiments in zebrafish are yet to be demonstrated.

Genetically-encoded sensors

Genetically-encoded sensors and expression reporters offer, in most cases, a more sensitive and more selective method to detect ROS and related signaling events than chemical probes. Belousov et al. have engineered a highly selective probe for H2O2 based on the prokaryotic H2O2-sensing protein OxyR [67,68]. The probe, named HyPer, consists of circularly permuted YFP inserted in the regulatory domain of OxyR (Fig. 1A). H2O2-mediated oxidation of cysteines in OxyR results in the formation of a disulfide bond, a conformational change in YFP and its excitation spectrum shift, characterized by an increased peak at 500 nm and a decreased peak at 420 nm. Reduction of the OxyR disulfide bond reverses the spectral shift. Niethammer et al. used HyPer to generate a transgenic H2O2 reporter zebrafish and studied spatiotemporal gradients of H2O2 in wound responses [69]. They have found that the wound-inflicted H2O2 gradient is created by dual oxidase (Duox), and that it is required for rapid recruitment of leukocytes to the wound. The HyPer transgenic zebrafish was also used in a different study to demonstrate that a Src family kinase Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte recruitment to the wound [70]. Cys466 in Lyn is responsible for direct oxidation-mediated activation of the kinase. This series of studies using transgenic zebrafish revealed that oxidation events occur before myeloid cell recruitment, and provided important spatiotemporal characteristics and mechanistic insights by identifying Duox as a source of H2O2 and Lyn as an oxidation sensor.

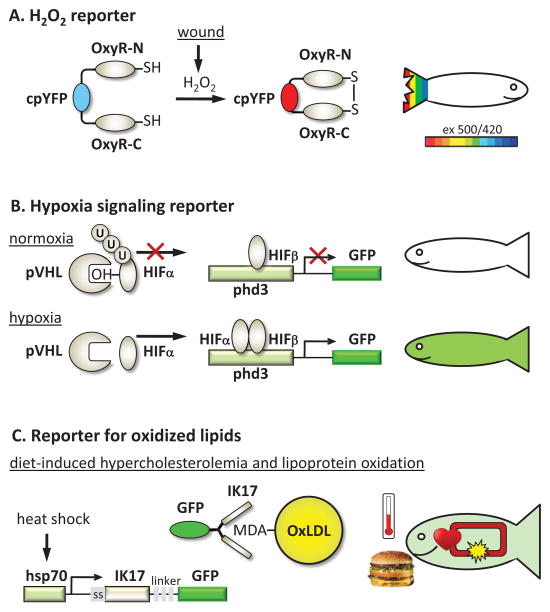

Figure 1. Transgenic reporter zebrafish to study ROS and oxidative processes.

A, H2O2 reporter. The HyPer construct expressed in zebrafish is a ratiometric sensor for H2O2. It uses the selectivity of cysteine oxidation by H2O2 in the bacterial protein OxyR and its subsequent conformational change. cpYFP inserted in the OxyR molecule responds to this H2O2-induced conformational change by the shift in its excitation spectrum: reduced emission with excitation at 420 nm and increased emission with excitation at 500 nm [67]. It is illustrated by blue color for a low YFP500/YFP420 ratio and red color for the high ratio. In zebrafish, wound inflicted to the tail fin induces a gradient of H2O2, sensed by Lyn kinase and leading to recruitment of neutrophils [69,70].

B, HIFα activity reporter. At normal oxygen tension, HIFα is specifically hydroxylated and binds with pVHL, which mediates HIFα ubiquitination and degradation. However, under hypoxic conditions, HIFα is not hydroxylated, becomes stabilized and translocates to the nucleus, where it associates with HIFα and activates a transcription program. Expression of Phd3 is one of the strongest responses to hypoxia, mediated by HIF. In zebrafish, the HIFβ activity reporter expresses GFP under control of the phd3 promoter [37].

C. Reporter for oxidized lipids. Feeding zebrafish a high-cholesterol diet results in rapid accumulation of lipid deposits in the vasculature and in lipoprotein oxidation [51,97]. One of the lipid oxidation-specific epitopes, LDL modified by malondialdehyde (MDA) is detected in the transgenic zebrafish vasculature by the GFP-tagged antibody IK17. The conditional expression of the secreted IK17-GFP antibody is under control of the hsp70 promoter and is transiently induced in zebrafish subjected to heat shock [96].

Oxygen and electrophile stimulated signaling events have been studied in transgenic zebrafish in which fluorescent proteins replaced coding regions of the proteins expressed in response to oxidative stress. Thus, Santhakumar et al. generated a zebrafish with EGFP expression driven by the phd3 promoter/regulatory elements (Fig. 1B) [37]. Phd3 is a robust target of Hif-mediated transcription and, thus, phd3 promoter-driven expression of EGFP is an indicator of hypoxia. Using this reporter zebrafish and vhl mutants, the authors established the role of pVhl as a genuine tumor suppressor [37]. Suzuki et al. used a similar approach to identify pi-class Gst as a target for Nrf2a in zebrafish [71]. They subsequently used a transgenic zebrafish expressing GFP under control of the gstp1 promoter to identify exogenous nitro-oleic acid as an activator of Keap1-Nrf2 [72]. The reporter was also sensitive to application of a cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2, but not of H2O2, suggesting that nitro-oleic acid and 15d-PGJ2 share an analogous cysteine code as electrophiles and also have similar anti-inflammatory roles. Kusik et al. generated a transgenic zebrafish expressing a luciferase–GFP fusion protein under the regulation of the electrophile response element (EPRE) [73]. This construct allows visual confirmation of transgene expression in live fish through fluorescence microscopy and quantitative assessment of gene expression by measuring luciferase activity in embryo extracts. This EPRE reporter zebrafish was used to detect mercury in aquatic environments.

The studies referred to in this section, most of them conducted in last 2–3 years, demonstrate the power of transgenic zebrafish models to monitor ROS and assess oxidation-dependent signaling events, as well as to address specific questions of embryonic development, inflammation, cancer and toxicology.

Lipoprotein oxidation in hypercholesterolemic zebrafish

In 2009, we suggested to use zebrafish as a model organism to study selected pathological events relevant to early development of human atherosclerosis [51]. Feeding zebrafish a HCD results in marked hypercholesterolemia and development of vascular lesions, which resemble early atherosclerotic lesions in humans and in hypercholesterolemic mice. Remarkably, hypercholesterolemia in zebrafish is associated with strong lipoprotein oxidation. Oxidative modification of LDL is widely believed to increase LDL atherogenicity and to drive the initial formation of atherosclerotic lesions in both humans and experimental animals [12,46,74]. Thus, the hypercholesterolemic zebrafish model, which is characterized by extremely high levels of OxLDL and oxidized lipids, offers attractive approaches to studying lipoprotein oxidation and its pro-atherogenic effects and to developing new diagnostic tools and therapies.

Immunoassays and mass spectrometry

Oxidation of LDL renders it immunogenic, and antibodies against oxidation-specific epitopes (OSE) in OxLDL arise naturally in patients with cardiovascular disease and in hypercholesterolemic animals. Witztum and colleagues have cloned an array of natural monoclonal antibodies that recognize OSE and have developed immunoassays to detect OSE in plasma of different animal species and in humans [75–81]. The monoclonal antibody EO6 is used to measure oxidized phospholipids (OxPL) in plasma LDL. This immunoassay has been used in over 25 published papers to assess OxPL/APOB levels in a large number of clinical trials and has proven to have a high prognostic value in predicting risk of cardiovascular disease [12,82–95].

The E06/APOB levels in HCD-fed zebrafish plasma are as much as 20–30 times higher than in plasma of control animals [51], the values that are rarely observed in human plasma. The EO6 immunoreactivity with APOA-I lipoproteins is as high as with APOB lipoproteins in zebrafish plasma, which is also unusual for human or mouse plasma.

Oxidized lipids in zebrafish larvae, the major focus of our vascular imaging studies [51,96], have been analyzed using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Because it is impractical to draw blood from a tiny zebrafish larva, the whole euthanized larvae were gently homogenized and bodily liquids collected. A 2-week HCD feeding resulted in a 4-fold increase in total cholesterol and triglycerides [58,97]. Non-oxygenated CEs (cholesteryl arachidonate, linoleate and oleate) were increased 4–13-fold in HCD-fed larvae, indicating increases in circulating lipoproteins and/or accumulation of lipid in tissues. Remarkably, oxygenated CEs were increased as much as 10–70-fold, suggesting that the HCD feeding leads to profound lipid oxidation. The OxCE molecules identified in HCD-fed zebrafish are also found in human and mouse atherosclerotic lesions and in plasma of patients with cardiovascular disease [97–99]. Some of these OxCE have been demonstrated to elicit proinflammatory and proatherogenic responses in endothelial cells and in macrophages [100–102].

We have also characterized non-oxidized and oxidized phosphatidylcholines (PC) in hypercholesterolemic zebrafish. While the levels of non-oxidized PC remained unchanged in HCD-fed zebrafish larvae, the levels of many lysoPC and OxPC increased 5–25 fold [97]. The OxPC analyzed include 1-palmitoyl-2-oxovaleroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POVPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(5,6-epoxyisoprostane E2)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PEIPC), and 1-palmitoyl-2-glutaryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PGPC), the OxPL molecules shown to induce numerous proinflammatory responses in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages [48,103–109]. The increased levels of lysoPC suggest activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2). In agreement, an increased PLA2 activity was detected in the vasculature of HCD-fed zebrafish larvae using a fluorogenic PLA2 substrate [51]. Homogenates of HCD-fed zebrafish larvae competed for oxidized LDL binding with macrophages and activated ERK, Akt and JNK and induced macrophage spreading, the effects characteristic for macrophages activated with oxidized LDL.

Why are zebrafish so prone to oxidative stress and lipid oxidation?

Papers reviewed in this article suggest that zebrafish possess rather sophisticated antioxidative systems, complete with oxygen- and electrophile-sensing signaling pathways and the enzymes that detoxify free radicals and replenish small molecule antioxidants. Then, why are zebrafish so sensitive to any insult, ranging from environmental pollutants to high-cholesterol feeding, and respond to these stimuli with extreme oxidative stress? This exacerbated oxidative response, of course, makes zebrafish an attractive model organism to study mechanisms and implications of oxidative stress, but it is also important to understand the causes of this phenomenon. Here, we will briefly consider three factors that may contribute to the susceptibility of zebrafish to oxidative stress – water, temperature and lipids, but as more data become available, the topic merits further detailed discussion.

Levels of dissolved oxygen in water vary significantly depending on the depth, turbulence, sediments and environmental pollutants. Fish deploy complex behavioral, physiologic and molecular strategies to maintain blood oxygenation, but intermittent hypoxia is inevitable. The metabolic response to hypoxia is to increase anaerobic respiration via glycolytic production of ATP. The glycolysis pathway inherently produces more ROS than the aerobic respiration.

Furthermore, zebrafish are an ectothermic organism, which regulates its body temperature largely by exchanging heat with its surroundings. This is in contrast to endothermic mammals who generate heat to maintain body temperature, typically above the ambient temperature. In wild, fish experience thermal fluctuations during day/night and seasonal cycles, which affect hemoglobin affinity to oxygen and are a stressor by itself. For example, exposure to cold increases activity of glycolytic enzymes in the brain of green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus) [110] and expression of glucose transporters and uncoupling proteins in the brain of zebrafish [111]. Thus, exposure to temperature fluctuations has predisposed zebrafish to activation of glycolysis as a defensive mechanisms, with its attendant oxidative stress.

Cooler body temperature in fish (zebrafish are maintained at 28.5°C) than in mammals also affects membrane lipid composition. Relatively high levels of unsaturated fatty acids help maintain membrane fluidity in species exposed to cold [112,113], but also make these membranes more susceptible to oxidation. In addition, as we discussed above, fish preferentially use lipids as an energy source and are hyperlipidemic, using standards applied to mammals [50]. Thus, predisposition to oxidative stress associated with hypoxia and anaerobic respiration, together with abundance of lipids that are easily oxidized, result in elevated lipid oxidation, the condition which is greatly exacerbated upon feeding zebrafish a HCD, as evident from our experiments [51,97].

In vivo imaging of lipid oxidation products with oxidation-specific antibodies

In the reports that we discussed so far, oxidized lipids were measured using immunoassays and mass spectrometry techniques in the materials obtained from euthanized zebrafish (blood draw is a terminal procedure in zebrafish). Although these analytical techniques provide important insights into lipid oxidation processes, a method to visualize oxidized lipids in live transparent zebrafish larvae would have clear advantages. The approach that we used was to image oxidized lipids using fluorescently tagged oxidation-specific antibodies. For these studies, we used the antibody IK17, cloned in the Witztum laboratory from a patient with advanced cardiovascular disease [79]. IK17 binds to malondialdehyde (MDA)-modified LDL and other MDA-modified proteins and stains mouse and human atherosclerotic lesions [79,90,114]. IK17-reactive epitopes are increased in thin cap fibroatheroma and in ruptured human lesions, suggesting their pathophysiological role and the importance in the identification of plaques vulnerable to rupture (Sotirios Tsimikas, personal communication).

Injection of recombinant antibodies

Feeding zebrafish larvae a HCD for as short as 5 days results in lipid accumulation in the vascular wall, which is the initial step in formation of human atherosclerotic lesions. The vascular lipid accumulation in zebrafish is visualized by supplementing the HCD with a fluorescent cholesterol ester (cholesteryl BODIPY 576/589 C11) and imaging live larvae under a confocal microscope. Bright red fluorescence in the vascular wall indicates vascular lipid accumulation. Since the BODIPY 576/589 fluorophore is on the acyl chain of the cholesterol ester, which is likely hydrolyzed in the digestive system, and the fluorescent fatty acid is then re-esterified into cholesterol esters, triglycerides and/or phospholipids, the red fluorescence represents all classes of lipids. To test whether these vascular lipid deposits contain MDA-modified proteins, we injected IK17 into HCD-fed zebrafish larvae. A single chain Fv fragment was cloned from the heavy and light chains of the IK17 Fab fragment and the recombinant IK17 antibody was expressed in E. coli, followed by its labeling with Alexa Fluor 488 [96]. The labeled single chain IK17 retained its binding to the MDA epitope. IK17-Alexa488 injection into the posterior cardinal vein resulted in the antibody binding to selected areas of lipid deposits in the vascular wall of HCD-fed zebrafish [96]. The incomplete colocalization of lipid and IK17 signals in larvae suggests that MDA epitopes accumulate only in selected areas of vascular lesions. This selective accumulation of IK17-specific epitopes in zebrafish vasculature agrees with the selective IK17 staining of mouse and human atherosclerotic lesions.

The approach of injecting recombinant labeled antibodies for imaging oxidized lipids in live zebrafish larvae has its own advantages and disadvantages. The procedure is quick and informative and thus suitable for initial characterization of the experimental system. However, it requires a skilled operator to inject intravenously into a tiny larva, the procedure that may be traumatic to the zebrafish. We found that the recombinant antibody must be endotoxin-free; otherwise, endotoxin induces non-specific binding of an antibody to the vasculature. The steps of producing, labeling and purification of the antibody may be time consuming. A different approach, using a transgenic zebrafish with conditional expression of IK17, as described below, gives a researcher the ability to simply and efficiently control transient antibody expression, repeatedly and at specified time points, and the opportunity to study therapeutic effects of diets, antioxidants, and oxidation-specific antibodies themselves, without repetitive injections of recombinant antibody.

Conditional expression of antibodies in transgenic zebrafish

The Tg(hsp70:IK17-EGFP) zebrafish that we have produced (Fig. 1C), transiently express IK17-EGFP only after heat shock [96]. Placing zebrafish larvae, which are normally maintained at 28.5°C, in water at 37°C larvae for 1 hour induces robust expression of the transgene in somites, but not in the vasculature. IK17-EGFP is secreted into the circulation and binds to the vascular lipid deposits and also is detected in other tissues, suggesting the presence of MDA throughout the body of hypercholesterolemic zebrafish. Zebrafish larvae tolerate a 1-hour long heat shock well and the heat shock can be repeated several times. This allows measuring the time course of MDA vascular deposition in the same animal. By using multi-color fluorescent microscopy, a researcher can correlate accumulation of MDA epitopes in the vasculature with the extent of overall lipid deposition (with a fluorescent lipid added to the diet), activation of PLA2, matrix metalloproteinases or other enzymes for which fluorogenic substrates are available, recruitment of macrophages or neutrophils to the vasculature (using transgenic zebrafish with mpeg1 or lyz promoter driven fluorescent proteins) [51,96] or any other pathologic process of interest. All measurements are performed in live animals, in time-dependent and quantitative manner.

We have used the Tg(hsp70:IK17-EGFP) zebrafish to test several hypotheses. First was that accumulation of oxidized lipids in the vasculature can be reversed by switching to normal diet to which no cholesterol was added. The possibility of such a reversal has been suggested by Tsimikas et al. who demonstrated that switching the Ldlr−/− mice in which extensive atherosclerosis was achieved by a 6-month long HCD, to a chow diet for additional 6 months resulted in little change in the atherosclerotic lesion area but in remarkable reductions in binding of a MDA-specific antibody [115]. In our Tg(hsp70:IK17-EGFP) zebrafish experiment, a 5-day feeding with a HCD led to vascular accumulation of IK17-positive MDA epitopes, which was completely reversed following an additional 5-day feeding with control diet.

Therapeutic effects of antioxidants and oxidation-specific antibodies

The second hypothesis tested with Tg(hsp70:IK17-EGFP) zebrafish was that the antioxidant probucol would reduce accumulation of MDA epitopes as well as the overall vascular lipid deposition in HCD-fed zebrafish. Probucol is a potent lipophilic antioxidant that can potently decrease atherogenesis in rabbits independent of changes in plasma cholesterol levels [116,117]. Probucol added to the zebrafish HCD reduced the areas of vascular lipid deposits. Even more profound was a reduction in the vascular lesions to which IK17-EGFP bound, with many lipid deposits devoid of IK17-reactive epitopes [96]. These studies agree with the results of other work in which other antioxidants were tested in zebrafish, albeit using different read-out measurements. Zebrafish cannot synthesize vitamin C; thus, feeding zebrafish a vitamin C-deficient diet resulted in robust oxidative stress as demonstrated by elevated levels of MDA, measured as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances [118]. Consumption of a vitamin E-deficient diet led to lower levels of long chain PUFA, which may be a result of either increased lipid peroxidation or an impaired ability to synthesize sufficient PUFA, or both [119].

The third hypothesis was that constitutive expression of IK17 in zebrafish would inhibit vascular lipid deposition. This hypothesis is based on the observations that IK17 inhibits MDA-LDL binding to macrophages and that raising the titers of antibodies to MDA-LDL by immunization or by adenovirus-delivered expression of IK17 is atheroprotective in mice and rabbits [90,120,121]. Homogenates of zebrafish expressing IK17-EGFP (i.e. following heat shock but not before that) indeed inhibited MDA-LDL binding to macrophages in vitro [96]. These results suggest that in vivo IK17 expression may have a therapeutic effect. To test this possibility, we subjected Tg(hsp70:IK17-EGFP) zebrafish to repeated heat shocks to ensure sustained IK17-EGFP expression during the whole HCD feeding period. The resulting vascular lipid accumulation was dramatically reduced. Moreover, when heat shock was applied for the first time only on the 5th day after the start of HCD feeding, the ensuing IK17-EGFP expression reduced the area of lipid deposits measured 5 days later. These studies suggest that oxidation-specific antibodies themselves may have therapeutic applications by binding to oxidized lipids and neutralizing their proinflammatory and proatherogenic effects.

Conclusions

In aggregate, the results of the studies reviewed in this paper strongly support the use of zebrafish as a model organism to study oxidative mechanisms and search for effective therapies to reduce detrimental effects of oxidative damage. Such studies may range from work seeking answers to fundamental question of inflammation, such as with transgenic HyPer zebrafish used for imaging of H2O2 gradients (Fig. 1A), to applied research, as with zebrafish expressing an oxidation-specific antibody (Fig. 1C). Several examples reviewed in this article suggest that the zebrafish model can enable rapid initial screening of interventions that can inhibit LDL oxidation and/or uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages. Although we have reviewed mostly the work dissecting lipid oxidation processes relevant to atherosclerosis, which is the focus of our own experimental studies, the evidence suggests that oxidative processes relevant to many other human diseases can be effectively studied using zebrafish models as well.

We think that the possibility to generate transgenic zebrafish greatly expands research capabilities to study oxidative mechanisms. Fluorescent protein-based reporter systems, such as those to detect H2O2, HIFα activity or oxidized lipids, as illustrated in Fig. 1, offer the greatest sensitivity and selectivity, as well as the possibility of conditional expression and time-resolved studies. Fluorescent microscopy allows multiplexing, and transgenic zebrafish can be crossed to produce complex, multi-color reporter systems or can be used in combination with small-molecule fluorescent assays. Another interesting application would be to over express or conditionally express enzymes involved in antioxidative defense or the enzymes that promote lipid oxidation, such as lipoxygenases. Combined with the reporter systems reviewed, these transgenic animals would provide valuable mechanistic insights into oxidative mechanisms and suggest methods to shift the balance toward reduction of oxidative damage, resolution of inflammation and eventually, the reversal of chronic inflammatory conditions.

Highlights.

Zebrafish respond with robust oxidative stress to many pathological stimuli

Genetically-encoded reporters enable monitoring of H202 and HIF and NRF2 activities

Feeding zebrafish a high cholesterol diet leads to excessive lipoprotein oxidation

Transgenic zebrafish with GFP-tagged antibody enables imaging of oxidized lipids

Fluorescent reporter zebrafish provide methods for in vivo antioxidant screening

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Systematic Approaches to Toxicology in the Zebrafish. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:433–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowling JJ, Arbogast S, Hur J, Nelson DD, McEvoy A, Waugh T, Marty I, Lunardi J, Brooks SV, Kuwada JY, Ferreiro A. Oxidative stress and successful antioxidant treatment in models of RYR1-related myopathy. Brain. 2012;135:1115–1127. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shao B, Zhu L, Dong M, Wang J, Wang J, Xie H, Zhang Q, Du Z, Zhu S. DNA damage and oxidative stress induced by endosulfan exposure in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1533–1540. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Zeng SF, Cao YF. Oxidative stress response in zebrafish (Danio rerio) gill experimentally exposed to subchronic microcystin-LR. Environ Monit Assess. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2457-0. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park KH, Cho KH. A zebrafish model for the rapid evaluation of pro-oxidative and inflammatory death by lipopolysaccharide, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, and glycated high-density lipoproteins. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011;31:904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho KH. Enhanced Delivery of Rapamycin by V156K-apoA-I High-Density Lipoprotein Inhibits Cellular Proatherogenic Effects and Senescence and Promotes Tissue Regeneration. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1274–1285. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Autreaux B, Toledano MB. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroder K. Isoform specific functions of Nox protein-derived reactive oxygen species in the vasculature. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010;10:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore K, Tabas I. Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:219–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ley K, Miller YI, Hedrick CC. Monocyte and Macrophage Dynamics During Atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1506–1516. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsimikas S, Miller YI. Oxidative Modification of Lipoproteins: Mechanisms, Role in Inflammation and Potential Clinical Applications in Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:27–37. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng X, Noyes MB, Zhu LJ, Lawson ND, Wolfe SA. Targeted gene inactivation in zebrafish using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nbt1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyon Y, McCammon JM, Miller JC, Faraji F, Ngo C, Katibah GE, Amora R, Hocking TD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Amacher SL. Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:702–708. doi: 10.1038/nbt1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley JE, Yeh JR, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Sander JD, Peterson RT, Joung JK. Rapid mutation of endogenous zebrafish genes using zinc finger nucleases made by Oligomerized Pool ENgineering (OPEN) PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander JD, Dahlborg EJ, Goodwin MJ, Cade L, Zhang F, Cifuentes D, Curtin SJ, Blackburn JS, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Qi Y, Pierick CJ, Hoffman E, Maeder ML, Khayter C, Reyon D, Dobbs D, Langenau DM, Stupar RM, Giraldez AJ, Voytas DF, Peterson RT, Yeh JR, Joung JK. Selection-free zinc-finger-nuclease engineering by context-dependent assembly (CoDA) Nat Methods. 2011;8:67–69. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang P, Xiao A, Zhou M, Zhu Z, Lin S, Zhang B. Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:699–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sander JD, Cade L, Khayter C, Reyon D, Peterson RT, Joung JK, Yeh JR. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babin PJ, Thisse C, Durliat M, Andre M, Akimenko MA, Thisse B. Both apolipoprotein E and A–I genes are present in a nonmammalian vertebrate and are highly expressed during embryonic development. PNAS. 1997;94:8622–8627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durliat M, Andre M, Babin PJ. Conserved protein motifs and structural organization of a fish gene homologous to mammalian apolipoprotein E. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:549–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meijer AH, Gabby Krens SF, Medina R, He IS, Bitter W, Ewa Snaar-Jagalska B, Spaink HP. Expression analysis of the Toll-like receptor and TIR domain adaptor families of zebrafish. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jault C, Pichon L, Chluba J. Toll-like receptor gene family and TIR-domain adapters in Danio rerio. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam SH, Chua HL, Gong Z, Lam TJ, Sin YM. Development and maturation of the immune system in zebrafish, Danio rerio: a gene expression profiling, in situ hybridization and immunological study. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2004;28:9–28. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho SY, Thorpe JL, Deng Y, Santana E, DeRose RA, Farber SA. Lipid metabolism in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;76:87–108. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)76006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford BD, Pilgrim DB. Ontogeny and regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in the zebrafish embryo by in vitro and in vivo zymography. Developmental Biology. 2005;286:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlegel A, Stainier DYR. Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein Is Required for Yolk Lipid Utilization and Absorption of Dietary Lipids in Zebrafish Larvae. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15179–15187. doi: 10.1021/bi0619268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho SY, Lorent K, Pack M, Farber SA. Zebrafish fat-free is required for intestinal lipid absorption and Golgi apparatus structure. Cell Metabolism. 2006;3:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Sar AM, Stockhammer OW, van der LC, Spaink HP, Bitter W, Meijer AH. MyD88 innate immune function in a zebrafish embryo infection model. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2436–2441. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2436-2441.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnault F, Etienne J, Noe L, Raisonnier A, Brault D, Harney J, Berry M, Tse C, Fromental-Ramain C, Hamelin J, Galibert F. Human lipoprotein lipase last exon is not translated, in contrast to lower vertebrates. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996;43:109–115. doi: 10.1007/BF02337355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi M, Itoh K, Suzuki T, Osanai H, Nishikawa K, Katoh Y, Takagi Y, Yamamoto M. Identification of the interactive interface and phylogenic conservation of the Nrf2-Keap1 system. Genes to Cells. 2002;7:807–820. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timme-Laragy AR, Van Tiem LA, Linney EA, Di Giulio RT. Antioxidant responses and NRF2 in synergistic developmental toxicity of PAHs in zebrafish. Toxicol Sci. 2009;109:217–227. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas DA, Perez-Munizaga DA, Centanin L, Antonelli M, Wappner P, Allende ML, Reyes AE. Cloning of hif-1alpha and hif-2alpha and mRNA expression pattern during development in zebrafish. Gene Expression Patterns. 2007;7:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Tiem LA, Di Giulio RT. AHR2 knockdown prevents PAH-mediated cardiac toxicity and XRE- and ARE-associated gene induction in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2011;254:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greer SN, Metcalf JL, Wang Y, Ohh M. The updated biology of hypoxia-inducible factor. EMBO J. 2012;31:2448–2460. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeligar SM, Machida K, Kalra VK. Ethanol-induced HO-1 and NQO1 Are Differentially Regulated by HIF-1+¦ and Nrf2 to Attenuate Inflammatory Cytokine Expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35359–35373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Rooijen E, Voest EE, Logister I, Korving J, Schwerte T, Schulte-Merker S, Giles RH, van Eeden FJ. Zebrafish mutants in the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor display a hypoxic response and recapitulate key aspects of Chuvash polycythemia. Blood. 2009;113:6449–6460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santhakumar K, Judson EC, Elks PM, McKee S, Elworthy S, van Rooijen E, Walmsley SS, Renshaw S, Cross SS, van Eeden FJ. A zebrafish model to study and therapeutically manipulate hypoxia signaling in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maeda Y, Suzuki T, Pan X, Chen G, Pan S, Bartman T, Whitsett JA. CUL2 Is Required for the Activity of Hypoxia-inducible Factor and Vasculogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16084–16092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710223200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elks PM, van Eeden FJ, Dixon G, Wang X, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Ingham PW, Whyte MKB, Walmsley SR, Renshaw SA. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (Hif-1alpha) delays inflammation resolution by reducing neutrophil apoptosis and reverse migration in a zebrafish inflammation model. Blood. 2011;118:712–722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB. The Nrf2-Antioxidant Response Element Signaling Pathway and Its Activation by Oxidative Stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13291–13295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900010200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Timme-Laragy AR, Karchner SI, Franks DG, Jenny MJ, Harbeitner RC, Goldstone JV, McArthur AG, Hahn ME. Nrf2b, novel zebrafish paralog of oxidant-responsive transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4609–4627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding F, Song WH, Guo J, Gao ML, Hu WX. Oxidative stress and structure-activity relationship in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) under exposure to paclobutrazol. J Environ Sci Health B. 2009;44:44–50. doi: 10.1080/03601230802519652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CT, Tseng WC, Hsiao NW, Chang HH, Ken CF. Characterization, molecular modelling and developmental expression of zebrafish manganese superoxide dismutase. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;27:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerhard GS, Kauffman EJ, Grundy MA. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the Danio rerio catalase gene. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2000;127:447–457. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(00)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin Y, Zhang X, Shu L, Chen L, Sun L, Qian H, Liu W, Fu Z. Oxidative stress response and gene expression with atrazine exposure in adult female zebrafish (Danio rerio) Chemosphere. 2010;78:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witztum JL. Beyond cholesterol. Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:915–924. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witztum JL, Steinberg D. The Oxidative Modification Hypothesis of Atherosclerosis: Does It Hold for Humans? Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2004;11:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller YI, Choi S-H, Wiesner P, Fang L, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Boullier A, Gonen A, Diehl CJ, Que X, Montano E, Shaw PX, Tsimikas S, Binder CJ, Witztum JL. Oxidation-Specific Epitopes are Danger Associated Molecular Patterns Recognized by Pattern Recognition Receptors of Innate Immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108:235–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson JL, Carten JD, Farber SA. Zebrafish lipid metabolism: from mediating early patterning to the metabolism of dietary fat and cholesterol. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;101:111–141. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387036-0.00005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babin PJ, Vernier JM. Plasma lipoproteins in fish. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:467–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoletov K, Fang L, Choi SH, Hartvigsen K, Hansen LF, Hall C, Pattison J, Juliano J, Miller ER, Almazan F, Crosier P, Witztum JL, Klemke RL, Miller YI. Vascular Lipid Accumulation, Lipoprotein Oxidation, and Macrophage Lipid Uptake in Hypercholesterolemic Zebrafish. Circ Res. 2009;104:952–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poupard G, Andre M, Durliat M, Ballagny C, Boeuf G, Babin PJ. Apolipoprotein E gene expression correlates with endogenous lipid nutrition and yolk syncytial layer lipoprotein synthesis during fish development. Cell and Tissue Research. 2000;300:251–261. doi: 10.1007/s004419900158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marza E, Barthe C, Andre M, Villeneuve L, Helou C, Babin PJ. Developmental expression and nutritional regulation of a zebrafish gene homologous to mammalian microsomal triglyceride transfer protein large subunit. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:506–518. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin SR, Cho KH. Water extracts of cinnamon and clove exhibits potent inhibition of protein glycation and anti-atherosclerotic activity in vitro and in vivo hypolipidemic activity in zebrafish. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JY, Seo J, Cho KH. Aspartame-fed zebrafish exhibit acute deaths with swimming defects and saccharin-fed zebrafish have elevation of cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity in hypercholesterolemia. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2899–2905. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smart EJ, De Rose RA, Farber SA. Annexin 2-caveolin 1 complex is a target of ezetimibe and regulates intestinal cholesterol transport. PNAS. 2004;101:3450–3455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400441101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Clifton JD, Lucumi E, Myers MC, Napper A, Hama K, Farber SA, Smith AB, Huryn DM, III, Diamond SL, Pack M. Identification of novel inhibitors of dietary lipid absorption using zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baek JS, Fang L, Li AC, Miller YI. Ezetimibe and simvastatin reduce cholesterol levels in zebrafish larvae fed a high-cholesterol diet. Cholesterol. 2012;2012:564705. doi: 10.1155/2012/564705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hermann AC, Millard PJ, Blake SL, Kim CH. Development of a respiratory burst assay using zebrafish kidneys and embryos. J Immunol Methods. 2004;292:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker SL, Ariga J, Mathias JR, Coothankandaswamy V, Xie X, Distel M, Koster RW, Parsons MJ, Bhalla KN, Saxena MT, Mumm JS. Automated Reporter Quantification In Vivo: High-Throughput Screening Method for Reporter-Based Assays in Zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shepherd J, Hilderbrand SA, Waterman P, Heinecke JW, Weissleder R, Libby P. A Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Myeloperoxidase Activity in Atherosclerosis-Associated Macrophages. Chemistry & Biology. 2007;14:1221–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun ZN, Liu FQ, Chen Y, Tam PKH, Yang D. A Highly Specific BODIPY-Based Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Hypochlorous Acid. Org Lett. 2008;10:2171–2174. doi: 10.1021/ol800507m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koide Y, Urano Y, Hanaoka K, Terai T, Nagano T. Development of an Si-Rhodamine-Based Far-Red to Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probe Selective for Hypochlorous Acid and Its Applications for Biological Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:5680–5682. doi: 10.1021/ja111470n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang YK, Cho HJ, Lee J, Shin I, Tae J. A rhodamine-hydroxamic acid-based fluorescent probe for hypochlorous acid and its applications to biological imagings. Org Lett. 2009;11:859–861. doi: 10.1021/ol802822t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng X, Jia H, Long T, Feng J, Qin J, Li Z. A “turn-on” fluorescent probe for hypochlorous acid: convenient synthesis, good sensing performance, and a new design strategy by the removal of C=N isomerization. Chem Commun (Camb ) 2011;47:11978–11980. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou Y, Li JY, Chu KH, Liu K, Yao C, Li JY. Fluorescence turn-on detection of hypochlorous acid via HOCl-promoted dihydrofluorescein-ether oxidation and its application in vivo. Chem Commun (Camb ) 2012;48:4677–4679. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30265a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belousov VV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, Staroverov DB, Shakhbazov KS, Terskikh AV, Lukyanov S. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Methods. 2006;3:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Markvicheva KN, Bilan DS, Mishina NM, Gorokhovatsky AY, Vinokurov LM, Lukyanov S, Belousov VV. A genetically encoded sensor for H2O2 with expanded dynamic range. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoo SK, Starnes TW, Deng Q, Huttenlocher A. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature. 2011;480:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki T, Takagi Y, Osanai H, Li L, Takeuchi M, Katoh Y, Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Pi class glutathione S-transferase genes are regulated by Nrf 2 through an evolutionarily conserved regulatory element in zebrafish. Biochem J. 2005;388:65–73. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsujita T, Li L, Nakajima H, Iwamoto N, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Ohashi K, Kawakami K, Kumagai Y, Freeman BA, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi M. Nitro-fatty acids and cyclopentenone prostaglandins share strategies to activate the Keap1-Nrf2 system: a study using green fluorescent protein transgenic zebrafish. Genes to Cells. 2011;16:46–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kusik BW, Carvan MJ, Udvadia AJ., III Detection of mercury in aquatic environments using EPRE reporter zebrafish. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2008;10:750–757. doi: 10.1007/s10126-008-9113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palinski W, Horkko S, Miller E, Steinbrecher UP, Powell HC, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL. Cloning of Monoclonal Autoantibodies to Epitopes of Oxidized Lipoproteins from Apolipoprotein E-deficient Mice. Demonstration of Epitopes of Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein in Human Plasma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:800–814. doi: 10.1172/JCI118853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horkko S, Miller E, Branch DW, Palinski W, Witztum JL. The epitopes for some antiphospholipid antibodies are adducts of oxidized phospholipid and beta 2 glycoprotein 1á(and otheráproteins) PNAS. 1997;94:10356–10361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hörkkö S, Bird DA, Miller E, Itabe H, Leitinger N, Subbanagounder G, Berliner JA, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Monoclonal autoantibodies specific for oxidized phospholipids or oxidized phospholipid-protein adducts inhibit macrophage uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:117–128. doi: 10.1172/JCI4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shaw PX, Hörkkö S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shaw PX, Hörkkö S, Tsimikas S, Chang MK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Chen PP, Witztum JL. Human-derived anti-oxidized LDL autoantibody blocks uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages and localizes to atherosclerotic lesions in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1333–1339. doi: 10.1161/hq0801.093587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Binder CJ, Shaw PX, Chang MK, Boullier A, Hartvigsen K, Horkko S, Miller YI, Woelkers DA, Corr M, Witztum JL. Thematic review series: The Immune System and Atherogenesis. The role of natural antibodies in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1353–1363. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500005-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tuominen A, Miller YI, Hansen LF, Kesaniemi YA, Witztum JL, Horkko S. A Natural Antibody to Oxidized Cardiolipin Binds to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein, Apoptotic Cells, and Atherosclerotic Lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000233333.07991.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsimikas S, Bergmark C, Beyer RW, Patel R, Pattison J, Miller E, Juliano J, Witztum JL. Temporal increases in plasma markers of oxidized low-density lipoprotein strongly reflect the presence of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:360–370. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsimikas S, Lau HK, Han KR, Shortal B, Miller ER, Segev A, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL, Strauss BH. Percutaneous coronary intervention results in acute increases in oxidized phospholipids and lipoprotein(a): short-term and long-term immunologic responses to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Circulation. 2004;109:3164–3170. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130844.01174.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsimikas S, Brilakis ES, Miller ER, McConnell JP, Lennon RJ, Kornman KS, Witztum JL, Berger PB. Oxidized Phospholipids, Lp(a) Lipoprotein, and Coronary Artery Disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:46–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsimikas S. Oxidative Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Cardiovascular Disease. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;98:S9–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mayr M, Kiechl S, Tsimikas S, Miller E, Sheldon J, Willeit J, Witztum JL, Xu Q. Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Autoantibodies, Chronic Infections, and Carotid Atherosclerosis in a Population-Based Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:2436–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kiechl S, Willeit J, Mayr M, Viehweider B, Oberhollenzer M, Kronenberg F, Wiedermann CJ, Oberthaler S, Xu Q, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidized Phospholipids, Lipoprotein(a), Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Activity, and 10-Year Cardiovascular Outcomes: Prospective Results From the Bruneck Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1788–1795. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tsimikas S, Brilakis ES, Lennon RJ, Miller ER, Witztum JL, McConnell JP, Kornman KS, Berger PB. Relationship of IgG and IgM autoantibodies to oxidized low density lipoprotein with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:425–433. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600361-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burke A, Cresswell N, Kolodgie F, Virmani R, Tsimikas S. Increased expression of oxidation-specific epitopes and Lp(a) reflect unstable plaques in human coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;49 :A299. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsimikas S, Miyanohara A, Hartvigsen K, Merki E, Shaw PX, Chou MY, Pattison J, Torzewski M, Sollors J, Friedmann T, Lai C, Hammond K, Getz GS, Reardon CA, Li AC, Banka C, Witztum JL. Human oxidation-specific antibodies reduce foam cell formation and atherosclerosis progression. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:1715–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arai K, Orsoni A, Mallat Z, Tedgui A, Witztum JL, Bruckert E, Tselepis AD, Chapman MJ, Tsimikas S. Acute impact of apheresis on oxidized phospholipids in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res. 2012 doi: 10.1194/jlr.P027235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leibundgut G, Arai K, Orsoni A, Yin H, Scipione C, Miller ER, Koschinsky ML, Chapman MJ, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidized phospholipids are present on plasminogen, affect fibrinolysis, and increase following acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1426–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taleb A, Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein oxidation biomarkers for cardiovascular risk: what does the future hold? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10:399–402. doi: 10.1586/erc.12.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ryu SK, Mallat Z, Benessiano J, Tedgui A, Olsson AG, Bao W, Schwartz GG, Tsimikas S. Phospholipase A2 enzymes, high-dose atorvastatin, and prediction of ischemic events after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2012;125:757–766. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fefer P, Tsimikas S, Segev A, Sparkes J, Otsuma F, Kolodgie F, Virmani R, Juliano J, Charron T, Strauss BH. The role of oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein (a) and biomarkers of oxidized lipoproteins in chronically occluded coronary arteries in sudden cardiac death and following successful percutaneous revascularization. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fang L, Green SR, Baek JS, Lee SH, Ellett F, Deer E, Lieschke GJ, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Miller YI. In vivo visualization and attenuation of oxidized lipid accumulation in hypercholesterolemic zebrafish. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4861–4869. doi: 10.1172/JCI57755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fang L, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Wiesner P, Choi SH, Almazan F, Pattison J, Deer E, Sayaphupha T, Dennis EA, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Miller YI. Oxidized cholesteryl esters and phospholipids in zebrafish larvae fed a high-cholesterol diet: macrophage binding and activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32343–32351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Almazan F, Dennis EA, Witztum JL, Miller YI. Cholesteryl ester hydroperoxides are biologically active components of minimally oxidized LDL. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10241–10251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hutchins PM, Moore EE, Murphy RC. Electrospray tandem mass spectrometry reveals extensive and non-specific oxidation of cholesterol esters in human peripheral vascular lesions. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:2070–2083. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M019174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choi S-H, Harkewicz R, Lee JH, Boullier A, Almazan F, Li AC, Witztum JL, Bae YS, Miller YI. Lipoprotein accumulation in macrophages via toll-like receptor-4-dependent fluid phase uptake. Circ Res. 2009;104:1355–1363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miller YI, Choi SH, Fang L, Harkewicz R. Toll-like receptor-4 and lipoprotein accumulation in macrophages. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009;7:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huber J, Boechzelt H, Karten B, Surboeck M, Bochkov VN, Binder BR, Sattler W, Leitinger N. Oxidized cholesteryl linoleates stimulate endothelial cells to bind monocytes via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:581–586. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000012782.59850.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Subbanagounder G, Wong JW, Lee H, Faull KF, Miller E, Witztum JL, Berliner JA. Epoxyisoprostane and epoxycyclopentenone phospholipids regulate monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and interleukin-8 synthesis. Formation of these oxidized phospholipids in response to interleukin-1beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7271–7281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boullier A, Friedman P, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Green SR, Almazan F, Dennis EA, Steinberg D, Witztum JL, Quehenberger O. Phosphocholine as a pattern recognition ligand for CD36. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:969–976. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400496-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berliner JA, Watson AD. A Role for Oxidized Phospholipids in Atherosclerosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:9–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee S, Gharavi NM, Honda H, Chang I, Kim B, Jen N, Li R, Zimman A, Berliner JA. A role for NADPH oxidase 4 in the activation of vascular endothelial cells by oxidized phospholipids. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;47:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cherepanova OA, Pidkovka NA, Sarmento OF, Yoshida T, Gan Q, Adiguzel E, Bendeck MP, Berliner J, Leitinger N, Owens GK. Oxidized Phospholipids Induce Type VIII Collagen Expression and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration. Circ Res. 2009;104:609–618. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bochkov VN, Mechtcheriakova D, Lucerna M, Huber J, Malli R, Graier WF, Hofer E, Binder BR, Leitinger N. Oxidized phospholipids stimulate tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells via activation of ERK/EGR-1 and Ca(++)/NFAT. Blood. 2002;99:199–206. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran AC, Johnstone SR, Elliott MR, Gruber F, Han J, Chen W, Kensler T, Ravichandran KS, Isakson BE, Wamhoff BR, Leitinger N. Identification of a Novel Macrophage Phenotype That Develops in Response to Atherogenic Phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res. 2010;107:737–746. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shaklee JB, Christiansen JA, Sidell BD, Prosser CL, Whitt GS. Molecular aspects of temperature acclimation in fish: contributions of changes in enzyme activities and isozyme patterns to metabolic reorganization in the green sunfish. J Exp Zool. 1977;201:1–20. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tseng YC, Chen RD, Lucassen M, Schmidt MM, Dringen R, Abele D, Hwang PP. Exploring Uncoupling Proteins and Antioxidant Mechanisms under Acute Cold Exposure in Brains of Fish. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cossins AR, Murray PA, Gracey AY, Logue J, Polley S, Caddick M, Brooks S, Postle T, Maclean N. The role of desaturases in cold-induced lipid restructuring. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:1082–1086. doi: 10.1042/bst0301082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hazel JR. Thermal adaptation in biological membranes: is homeoviscous adaptation the explanation? Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:19–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Briley-Saebo KC, Nguyen TH, Saeboe AM, Cho YS, Ryu SK, Volkova ER, Dickson S, Leibundgut G, Wiesner P, Green S, Casanada F, Miller YI, Shaw W, Witztum JL, Fayad ZA, Tsimikas S. In vivo detection of oxidation-specific epitopes in atherosclerotic lesions using biocompatible manganese molecular magnetic imaging probes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsimikas S, Shortal BP, Witztum JL, Palinski W. In Vivo Uptake of Radiolabeled MDA2, an Oxidation-Specific Monoclonal Antibody, Provides an Accurate Measure of Atherosclerotic Lesions Rich in Oxidized LDL and Is Highly Sensitive to Their Regression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:689–697. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Parthasarathy S, Young SG, Witztum JL, Pittman RC, Steinberg D. Probucol inhibits oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:641–644. doi: 10.1172/JCI112349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Carew TE, Schwenke DC, Steinberg D. Antiatherogenic effect of probucol unrelated to its hypocholesterolemic effect: evidence that antioxidants in vivo can selectively inhibit low density lipoprotein degradation in macrophage-rich fatty streaks and slow the progression of atherosclerosis in the Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7725–7729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kirkwood JS, Lebold KM, Miranda CL, Wright CL, Miller GW, Tanguay RL, Barton CL, Traber MG, Stevens JF. Vitamin C Deficiency Activates the Purine Nucleotide Cycle in Zebrafish. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3833–3841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lebold KM, Jump DB, Miller GW, Wright CL, Labut EM, Barton CL, Tanguay RL, Traber MG. Vitamin E deficiency decreases long-chain PUFA in zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Nutr. 2011;141:2113–2118. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Palinski W, Miller E, Witztum JL. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:821–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Freigang S, Horkko S, Miller E, Witztum JL, Palinski W. Immunization of LDL ReceptorûDeficient Mice With Homologous Malondialdehyde-Modified and Native LDL Reduces Progression of Atherosclerosis by Mechanisms Other Than Induction of High Titers of Antibodies to Oxidative Neoepitopes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1972–1982. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.12.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]