Abstract

Although sequencing a single human genome was a monumental effort a decade ago, more than one thousand genomes have now been sequenced. The task ahead lies in transforming this information into personalized treatment strategies that are tailored to the unique genetics of each individual. One important aspect of personalized medicine is patient-to-patient variation in drug response. Pharmacogenomics addresses this issue by seeking to identify genetic contributors to human variation in drug efficacy and toxicity. Here, we present a summary of the current status of this field, which has evolved from studies of single candidate genes to comprehensive genome-wide analyses. Additionally, we discuss the major challenges in translating this knowledge into a systems-level understanding of drug physiology with the ultimate goal of developing more effective personalized clinical treatment strategies.

Keywords: Pharmacogenomics, genome-wide association studies, next-generation sequencing, 1000 genome project, personalized medicine

Genetic variation likely contributes substantially to the variation in drug response observed across human populations. The field of pharmacogenomics, which seeks to relate genetic variability to variability in human drug response, has evolved considerably from candidate gene studies to studies of variation across whole genomes of human populations containing individuals who exhibit a range of responses to different drugs. The initial successes in the field often identified genetic variants within drug metabolizing genes that had large effects on sensitivity to a given drug. The field has since broadened in scope to encompass regulatory mutations, and refined techniques have allowed the identification of mutations with smaller effect sizes. Whereas early pharmacogenomics studies sought primarily to identify associations between common genetic variation and drug response, more recent approaches have begun to identify mRNAs, microRNAs, and other downstream events that are influenced by genetic variation and may underlie variation in pharmacologic responses.

A primary aim of pharmacogenomics has been to uncover novel human genetic variants that affect therapeutic response phenotypes and to identify the genes responsible for those phenotypic differences. The ultimate goal of the field has been to use an understanding of these relationships to devise novel personalized pharmacological treatment strategies that maximize the potential for therapeutic benefit and minimize the risk of adverse side effects for any given medication. The potential cost savings (via increased drug efficacy) and decreased morbidity and mortality (via increased drug safety) is immense. Advances in DNA sequencing and polymorphism characterization technologies have driven the field from a hypothesis-driven approach to a discovery-oriented, genome-wide approach that requires few assumptions regarding which variants are most relevant for outcome. Candidate gene approaches resulted primarily in the identification of genetic variants in drug metabolizing genes with large effects on toxicity or response [1], however, many genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified novel associations between drug response and genetic variants with unknown functional relevance and often with relatively small effect sizes [2]. The recent development of high-throughput sequencing techniques has allowed researchers to begin to examine the contribution of rare variants to drug sensitivity [3]. Although many important discoveries have been made, several challenges remain before the dream of personalized medicine will be realized. First, we must move from collecting large numbers of identified genetic variants to systematically analyzing them. Second, we must find ways to turn this systematic biological understanding into clinical strategies for treatment. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of recent exciting trends towards meeting these challenges.

Evolution of analytical methods for pharmacogenomic discovery

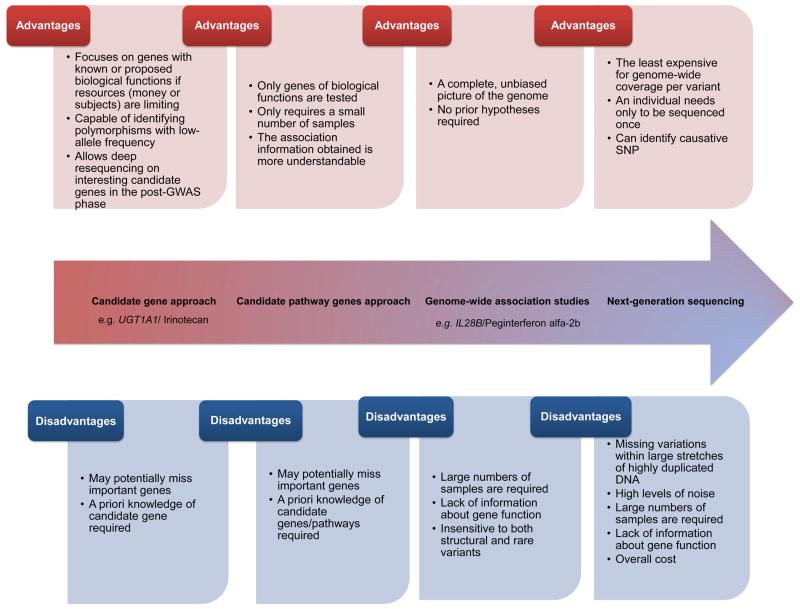

As shown in Figure 1, candidate gene approaches aim to study the relationship between either a single gene or a group of pathway-related genes and a drug-related phenotype. The single gene approach offers the advantage that highly relevant genes can be prioritized and tested first. This approach places greater burden on the researcher to choose good candidates. The pathway gene approach involves studying several candidate genes that function together to carry out related functions. Examples of pathways are genes related to drug metabolism (pharmacokinetics) or to drug responses (pharmacodynamics). A primary advantage of the candidate pathway gene strategy is the ability to identify effects of an aggregate of genes on a phenotype in circumstances where individual genes have small effects on the downstream phenotype. In addition, the association information of gene pathways may be more immediately understandable than single genes with regard to the mechanism of drug action [4]. However, the potential always exists that important unknown genes will be missed because only genes which are thought a priori to be involved in drug response are included in the study. Obviously, the success of this approach is heavily dependent on the assumptions underlying the selection of genes to be studied. Unexpected genes that play an important role in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drugs would remain undiscovered.

Figure 1. The evolution of pharmacogenomics.

The diagram depicts the different advantages and disadavantages for candidate gene approaches, candidate pathway genes approaches, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and next-generation sequencing. New techniques (e.g., GWAS) do not necessarily replace old strategies (e.g., candidate gene approach). Examples of the candidate gene approach include the gene/drug pairs (UGT1A1/Irinotecan). Examples of GWAS include the gene/drug pairs (/IL28B/Peginterferon alfa-2b).

Technologies for DNA genotyping and sequencing have undergone several evolutionary, if not revolutionary, steps of advancement. Genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can now be performed at high density relatively cheaply with microarrays. At the same time, the rapidly decreasing cost of sequencing allows for entire genomes to be sequenced much more economically than before, thus enabling novel polymorphisms and rare mutations to be characterized. Thus the pharmacogenetic studies of yesterday (that relied heavily on candidate gene approaches) have evolved into pharmacogenomics studies (using genome-wide analysis approaches). Generally, the limitations of candidate gene approaches have been solved by genome-wide approaches, which offer a more complete and unbiased picture of significant genome relationships. Several discovery and replication GWAS have successfully identified variants associated with pharmacogenomic phenotypes [2].

GWAS are not without problems, however, and these problems are not unique to pharmacogenomics. GWAS are generally insensitive to both structural and rare variants [5], although these are not likely to be a significant proportion of the total variation. Furthermore, the high number of false positive results is a substantial problem that continues to plague GWAS. Because it is difficult to functionally validate the large number of GWAS hits, results of replication cohorts are essential for building confidence in identified associations, narrowing the number of hits to be followed up on [5]. Additionally, large sample sizes are required to generate enough statistical power to overcome the multiple hypotheses that are often tested in GWAS [5]. Finally, even once a variant is identified, there is often little information to suggest its functional relevance [5]. Several approaches were developed to mitigate this last problem including the use of more biologically relevant endophenotypes, intermediate outcomes between the genotype and phenotype (Box 1).

Box (1). The endophenotype concept.

The term “endophenotype” was coined in 1966 to distinguish between exophenotype (external) and endophenotype (internal) [72]. Gottesman and Shields [73] defined an endophenotype to be “an internal phenotype discoverable by microscopic examination or biochemical test”. Endophenotype is referred to as an intermediate outcome that is generally closer to the phenotype than to the genotype [74]. In general, an endophenotype must meet the following criteria [75]: (i) it must be linked with an illness in a population, (ii) it must be heritable, (iii) it must manifest itself whether or not the illness is active, and(iv) it must co-segregate with an illness in families. The endophenotype concept has been extensively utilized in studies of psychiatric disorders (reviewed in [76]). This might have been because of the difficulty in precisely quantifying psychiatric disorder criteria. Recently, the endophenotype concept has been applied more broadly in genetic analyses of complex diseases [77]. For pharmacogenomic studies, one of the reasons for the introduction of this concept was the complexity of the processes that affect drug response and toxicity. It is generally easier to focus on a small group of genetic variants that have a large effect on the endophenotype, such as myotoxicity, the most common side effect of statins. The pathophysiology of this toxicity is not fully understood. Therefore, toxicity is defined in clinical trials by looking at a proxy, creatine kinase levels, which, if greater than 10 fold the normal value, indicates toxicity [78]. Similarly, the read out for the toxic effect caused by inhibitors of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VSP) signaling pathway (e.g., sorafenib) is hypertension [79]. Quantitative changes in blood pressure rather than elevation above a pre-defined threshold is used as an endophenotype in this case. The use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring has allowed more confident measurements than office checks as it can provide 40–100 measurements/day [80]. This could help in the selection of the proper VSP inhibitor and its appropriate dose [79]. Another example of an endophenotype is an increase in alanine transaminase [81], which is indicative of drug-induced liver dysfunction. A non-TT genotype at GGH (gamma-glutamyl hydrolase), T16C, is associated with significant risk of liver failure in Japanese patients, as the C allele may alter the activity of the GGH enzyme [81]. To help further assess drug responses, the Phenotype Standardization Project (PSP) was initiated in order to define in detail three different types of adverse drug reaction: drug-induced liver injury, drug-induced skin injury, and drug-induced torsade de pointes that were used in GWAS [82].

The candidate gene approach still plays a role even in the era of GWAS [6]. For example, this approach will be needed when looking at polymorphisms with low allele frequency. Additionally, it will be needed in the post-GWAS phase to follow up with functional validation studies or for deeper resequencing of interesting candidate genes that showed convincing association in earlier GWAS [6]. Another potential useful function of a candidate gene approach is to validate a GWAS by being “found” within the GWAS. Examples of this include a GWAS that identified the aspartate metabolism pathway as a contributing factor in asparaginase sensitivity [7] and the presence of variants in DNA repair and glutathione genes in a GWAS focused on platinating agents [8].

It is clear that the trend towards GWAS will continue, and likely even accelerate, although these studies may be aided by candidate approaches. Table 1 shows a list of published pharmacogenomics GWAS between 2010 and 2012. One recent successful GWAS examined adverse reactions induced by flucloxacillin, which is an antimicrobial agent used to treat gram-positive infections that works by inhibiting the synthesis of bacterial walls. The major adverse reaction to flucloxacillin is drug-induced liver injury (DILI). A GWAS was carried out using 51 cases and 282 controls matched for ancestry and sex [9]. The study showed that a SNP in complete linkage disequilibrium with HLA-B*5701 is associated with DILI. This was then confirmed in flucloxacillin-tolerant controls and replicated in a second cohort [9].

Table 1.

List of published pharmacogenomics genome wide association studies between years 2010–2012

| Drug | Response/toxicity | Number of cases | Genome-wide significance/replication | Lowest P- value | significant gene(s) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), either alone or in combination with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) | Diarrhoea, haematologic, mucositis, nausea/vomiti ng, neuropathy (FOLFOX only) | 221, 791 | No/Yes | P=1.076×10−05 | None | [83] |

| Antipsychotics (Olanzapine, Perphenazine, Quetiapine, Risperidone and Ziprasidone) | QT prolongation | 738 | Yes/No | 1.54 × 10−7 | SLC22A23 | [84] |

| Pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RBV) | Thrombocyto penia | 303, 391 | Yes/Yes | 8.17 × 10−9/5.29 × 10−17(combined) | DDRGK1 | [85] |

| Cisplatin | Cytotoxicity | 283 ethnically diverse LCLs, 222 small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and 961 non-SCLC (NSCLC) patients | No/Yes | 1.66 × 10−7 | None | [86] |

| Nevirapine | Rash | 149,233 | Yes/Yes | 1.6 × 10−4, 2.6 × 10−5 | CCHCR1 | [87] |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Musculoskeletal adverse events (MS-AEs) | 878 | Yes/No | 6.67×10−7 | TCL1A | [88] |

| Carboplatin | Carboplatin sensitivity (cell model), progression-free survival (PFS) (patients) | 87 (discovery), 54 (replication ), Phase I validation (377), Phase II validation (1326) | Yes/Yes | 9.84×10−6 | ALDH2 | [89] |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Difference in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) | 418,407 | Yes/Yes | 2.09×10−6 6.13×10−6 (Combined p value) |

T-gene | [90] |

| Inhaled glucocorticoids | Difference in FEV1 | 118, 935 | Yes/Yes | 7×10−4 | GLCCI1 | [91] |

| Carbamazepine | Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (cADRs) | 935, 60 | Yes/Yes | 1.18 × 10−13 3.64 × 10 −15 |

HLA-A | [92] |

| Gemcitabine plus either bevacizumab or placebo | Overall survival | 351 | Yes/No | 9.51 × 10−7 | (IL)17F | [93] |

| Antipsychotics | Extrapyramid al symptoms (EPS) | 409 | No/No | 8.953×10−6 | None | [94] |

| Citalopram | Clinical scoring for response in depression | 1,948 | No/No | 5×10−7 (response) 4×10−7 (remission) |

None | [95] |

| Epirubicin | Leukopenia | 473, 48 | Yes/Yes | 1.59 × 10 −7 2.27×10−9 (combined) |

microcephalin 1 | [96] |

| Lamotrigine- and phenytoin | Hypersensitivity reactions | 1386 | No/No | None was significant | None | [97] |

| Fenofibrate | Systematic inflammation | 1092 | No/No | None was significant | None | [98] |

| Allopurinol | Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) | 1005 | Yes/No | 2.44 × 10−8 | BAT1, HCP5, and MICC | [99] |

| Lumiracoxib | Liver injury | 217, 503 | Yes/Yes | 4.4 × 10−12 6.8 × 10−25 |

HLA | [100] |

| Aspirin | Aspirin intolerant asthma | 180,592 | Yes/Yes | 6.0×10−5 3 × 10 −5 |

CEP68 | [101] |

| Angiotensin- converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | Blood pressure response | 1023, 428 | Yes/Yes | 3.0 × 10 −25 2.3 × 10 −10 |

ABO gene | [102] |

| Amoxicillin- clavulanate | Drug-induced liver injury | 733,396 | Yes/Yes | 4.8 × 10−14 5×10−10 |

HLA | [103] |

| Carbamazepine | Hypersensitivity reaction | 4052, 145 | Yes/Yes | 3.5×10−8 1.1×10−6 |

HLA | [104] |

| Bisphosphonate | Osteonecrosis of the jaw | 107 | Yes/No | 7 × 10−8 | RBMS3 | [105] |

The continued evolution of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms has resulted in a dramatic drop in both the time and cost for genome sequencing [10], leading to a rapid increase in its usage in pharmacogenomics. The 1000 Genomes Project uses these state-of-the-art high-throughput sequencing technologies for the in-depth characterization of human genome sequence variation. The goal for this project is to describe more than 95% of the variants with an allele frequency of at least 1% in each of five major populations [11]. As many of the samples in the 1000 Genomes Project were also International HapMap lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) the project will provide a comprehensive resource for studying the relationship between genotype and cellular phenotype [12].

One of the problems associated with GWAS is that they have thus far been unable to detect the effect of rare SNPs on drug response and toxicity. The size of the pharmacogenomics GWAS has dramatically limited their statistical power. In order to increase the power of GWAS with smaller sample sizes, a new method was developed that incorporates rare variants. It examines the degree of correlation between uncommon alleles and drug response. If these genes are associated with an atypical drug response, then they are considered predictive pharmacogenes [13]. Applying this method on warfarin GWAS data [14] resulted in the identification of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 as warfarin pharmacogenes, although the original study reported only VKORC1 as significant [13]. Pharmacogenomic studies have begun to use data from the 1000 Genomes Project. A recent application showed that the imputation of 1000 Genomes Project SNPs in pathways identified by pharmacometabolomic data can improve and accelerate pharmacogenomics studies [15]. In cell-based studies (described below), the 1000 Genomes Project data can provide valuable information regarding rare variants that contribute to cellular pharmacologic phenotypes.

Examples of pharmacogenomic gene-drug pairs

Personalized drug therapy is especially desirable where the therapeutic index is narrow (i.e., having little difference between toxic and therapeutic doses) and when the consequences of drug toxicity are life-threatening [16]. These drugs (including antineoplastics, anticoagulants, and anti-HIV therapeutics) are often administered at maximally tolerated doses, which are typically chosen from population averages, resulting in up to one-third of treated patients developing toxicity and a significant proportion of treated patients exhibiting poor or no response. Drugs modulating hemostasis, such as clopidogrel and warfarin, have narrow therapeutic indexes, and genetic variability in the cytochromes P450 (CYPs) can influence outcome [17, 18]. Warfarin remains the most widely used anticoagulant [19], and the identification of genetic variants associated with toxicity of this drug is particularly important because high levels of this drug can cause internal bleeding. Variance in warfarin toxicity can be explained by heritable differences in CYP2C9 and in the vitamin K oxidoreductase complex-1, VKORC1, an enzyme involved in the drug’s mechanism of action. Genetic testing is estimated to reduce risk of hospitalization by as much as 30% [20]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed the label for warfarin twice; in 2007 the FDA indicated that genotyping of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 may be useful in the determination of the initial dose [21]. In 2010, the label was updated to include recommended dosage ranges [22].

Another example of a well-characterized gene-drug pair is clopidogrel, a drug used in combination with aspirin to prevent atherothrombosis after acute myocardial infarction [23]. It requires the transformation to an active metabolite by CYP enzymes [24]. The active metabolite then binds to adenosine diphosphate P2Y12, which inactivates the fibrinogen receptor, which is involved in platelet aggregation [23]. Early studies showed that patients with the allelic variant CYP2C19*2 had generally lower levels of the active metabolite, which led to reduced platelet inhibition activity and higher rates of cardiac events, particularly thrombosis, compared to controls [24]. Several studies have confirmed these results and further linked other loss-of-function CYP2C19 allelic variants to undesirable cardiovascular system effects following treatment with clopidogrel [17, 23, 25]. A recent study showed that if the patient was a CYP2C19*2 heterozygote, then tripling the maintenance dose could achieve platelet inhibition results similar to noncarriers that were administered the regular dose [26]. Surprisingly, another study showed that CYP2C19 loss-of-function did not alter the safety and efficacy of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes [27]. An alternative to clopidogrel is ticagrelor, which is a new-generation antiplatelet agent that reversibly, directly, and noncompetitively antagonizes the P2Y12 receptor. Recently, it was shown that the efficacy of ticagrelor was not affected by the CYP2C19 genotype. Ticagrelor was more efficacious than clopidogrel even in individuals predicted to be clopidogrel responders [28]. There may be other unknown variants that could affect the efficacy of ticagrelor. Identifiying these variants would allow clinicians to better individualize treatment according to the needs of the each patient.

Lastly, recent statistics have indicated that more than 170 million individuals worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) [29]. Complications of this infection include liver cirrhosis, hepatic injury, and hepatic fibrosis [30]. Over the last decade, peginterferon has been used alone or in combination with ribavirin for 24–48 weeks as the standard of care for the treatment of this infection [30]. Patients who respond to this standard of care achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR) that is associated with good quality of life [30]. Several independent GWAS showed that genetic variation in IL28B was associated with the positive response to this combination of drugs [29, 31, 32]. This genetic variation was also able to predict treatment response in the HCV patients co-infected with HIV [33] [34]. These are just a few examples of drug-gene pairs of significance to the healthcare community.

Cell-based models to complement clinical studies

Clinical studies, like those described above, contributed greatly to the success of pharmacogenetics discoveries [35]. According to the clinicaltrials.gov website, there are more than 650 clinical trials that involve pharmacogenomics and many of them are still recruiting patients. Although humans are the most relevant model, there are problems with accruing large numbers of patients receiving the same dose of drug without confounders such as concomitant medications, diet, and other variables. Large clinical trials are extremely expensive and require the coordination of many individuals. Some of the challenges with clinical trials can be circumvented by using cell-based models for either discovery or replication of pharmacogenomic findings.

One cell-based model that has emerged as a promising model system in the study of the genetics of drug response is the use of human Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). The cells provide a cost-effective testing system in which environmental factors can be controlled [36]. Combining this with information from HapMap LCLs, which includes publicly available genotype and sequencing data, enables GWAS between HapMap/1000 Genomes Project variants and pharmacologic phenotypes measured in the LCLs after drug or radiation treatment such as cell growth inhibition, changes in gene expression, intracellular concentration of drug/metabolite, and apoptosis. Recent studies from a number of groups using preclinical cell-based models have taken top GWAS hits (i.e., SNPs with lowest P-values) from these models and validated them in prospective clinical trials [37–39].

Cell lines can also be employed for follow-up functional studies because the genetic architecture and expression environment of the International HapMap LCLs is known. The most commonly used phenotypes in cell based models are the following: cell growth inhibition (IC50) [40], apoptosis [41], gene expression either at baseline or after treatment [42], and transport of drug molecules[43]. However, there are some drawbacks to using cell-based models. For example, important CYP450 enzymes are not expressed in LCLs, there may be in vitro confounders, and the generation of these cell lines from a limited number of tissues are the major limitations of this model [36].

Nevertheless, cell-based models have been applied successfully to various aspects of pharmacogenomics, including pharmacogenomics discovery [44], transcriptional profiling and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) studies [45], studies of interethnic differences in drug response [46, 47], and heritability analyses [48–50]. Additionally, discoveries using cell-based models have been translated into clinical findings. For example, to understand the inter-individual differences in asparginase sensitivity in patients treated for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the results obtained via genome-wide pathway analysis in HapMap LCLs were validated in ALL leukemic blast samples [7]. Both indicated that SNPs in the aspartate metabolism pathway were associated with asparaginase sensitivity in patients [7]. Another example is that one of the top SNPs from a GWAS of carboplatin sensitivity in HapMap LCLs was replicated in an initial analysis of patients receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel but was not significant in patients from multiple cohorts [38]. This study emphasizes the need for extensive validation in patients for predictors discovered via a cell-based approach. Additionally, to understand the genetic basis of variability in the response to platinum-based chemotherapy in lung cancer patients, both LCLs and lung cancer patients were examined [51]. A GWAS for cisplatin cytotoxicity in 283 LCLs resulted in a list of 157 top SNPs, of which nine and 10 were correlated with overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer patients, respectively [51]. Unfortunately, these SNPs were not significant after adjusting for multiple testing but follow-up studies confirmed the functional effect of genes correlated with these SNPs in cisplatin response in vitro. Additional replicates in independent samples of patients are still needed to validate the findings.

The advantage of GWAS is the simultaneous, unbiased testing of millions of SNPs; the challenge is that functional information is absent for the vast majority of loci that are implicated in a particular phenotype. To overcome this challenge, the LCL model can be used to study the function of the identified variants. In addition to the genetic data, baseline expression data using Affymetrix exon [52] and Illumina expression arrays[53], miRNA data using Exiqon arrays [54], and DNA methylation patterns [55] are available. This data can be combined to assign endophenotypes, which can then be used to reduce the complexity of GWAS (Box 1). Protein data will also be highly valuable in determining the function of variants. Pharmacologic GWAS results are enriched for eQTLs [56], providing a starting point for investigating the function of the pharmacologically associated variants in cell-based models.

Implementation of pharmacogenomic discoveries

There is a growing consensus that pharmacogenomic biomarkers will be a chief player in health care [57]. Although a large number of studies on pharmacogenomic discoveries have appeared in the literature, the majority have not migrated into clinical laboratories. This is due in part to the lack of reproducibility of some gene/drug pairs and the questionable utility of the findings in a large population [58]. This problem is aggravated in countries with developing or emerging economies, as the evidence for pharmacogenomics testing is often based on a population different than their own [59]. Evidence from large-scale prospective randomized clinical trials is lacking, but several are currently in progress [58]. PREDICT is an example of a double-blind prospective randomized trial of a pharmacogenetic test to prevent side effects [60]. It demonstrated the utility of HLA-B*5701 screening for the prediction of the incidence of immunologically-confirmed hypersensitivity reaction n patients administered abacavir [60]. Abacavir is now one of the most successful examples of pharmacogenomics testing integrated into clinical practice, indicating the efficacy of this type of trial.

A second hurdle to using pharmacogenomics in the clinic is economic [61]. Many physicians feel the costs of genotyping outweigh its potential benefits [62]. However, the notion that genotype-guided therapy is not cost-effective may be incorrect. For example, a recent study showed with mathematical modeling that genotype-guided clopidogrel therapy for specific patients was more cost-effective than prescribing it or its alternative, prasugrel, for all patients [63]. Other issues holding up wide-spread use of pharmacogenomics related to the clinical laboratory include the need for genotyping accuracy and trained clinicians with adequate expertise to interpret test results [64]. A recent survey indicated that the lack of physician knowledge and awareness is a major challenge for the implementation of pharmacogenomics testing [59]. Finally, privacy concerns and electronic tracking of diagnostic information also pose a challenge to this new era of medicine [61].

Developing companion diagnostic tests in conjunction with therapeutics allows the design of better clinical trials and eventually better implementation of pharmacogenomics testing [65]. In July 2011 the FDA released draft guidelines that required companion diagnostic tests to be approved simultaneously with their accompanying therapies if necessary for safe and effective use of the medication [65]. A recent survey showed that an average of 30–50% of drugs under development have an accompanying biomarker program, but only 10% of them are expected to be launched with a companion diagnostic in the next 5–10 years [61]. Examples of drugs approved recently by FDA with their companion tests are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The most recently FDA approved drugs with their companion diagnostics tests

| Drug name | Cancer type | Mechanism | Companion diagnostic | Approval date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zelboraf (Vemurafenib) | BRAF V600E mutation -positive, inoperable or metastatic melanoma. | a BRAF inhibitor, blocks the function of the V600E-mutated BRAF protein. | Cobas 4800 BRAF V600 Mutation Test (Roche) | August 2011 |

| Xalkori (Crizotinib) | Late-stage, non- small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) expressing the abnormal anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene. | Blocking certain kinases, including the protein produced by the abnormal ALK gene | Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe Kit | August 2011 |

Consortiums to move pharmacogenomics forward

As a result of substantial advances in the field of pharmacogenomics, the FDA has begun to update the labels of many drugs to include information about pharmacogenes to guide therapeutic strategies. A complete list of the drug genotype pairs cited by FDA mandated labels can be found online (http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm). In terms of research dedicated to this field, the National Institute of Health initiated the Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) to implement studies in basic, translational, and clinical science to advance pharmacogenomics in 2000 (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/FeaturedPrograms/PGRN/). PharmGKB, the premier public site that curates knowledge about the impact of genetics on drug response for clinicians and researchers works closely with PGRN to disseminate knowledge gained within and outside of this network (http://www.pharmgkb.org/). Another offshoot of the PGRN network is the Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC), which has the goal of gathering evidence for clinical implementation of drugs [66]. CPIC was formed in late 2009 in order to solve issues preventing the implementation of pharmacogenomics [66]. To date, CPIC has provided guidelines for HLA-B/abacavir [60], CYP2D6/codeine [67], TPMT/thiopurines [68], CYP2C9 and VKORC1/warfarin [22], and CYP2C19/clopidogrel [69]. Outside the United States, the Pharmacogenetics Working Group within the Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy is working to develop pharmacogenetics-based therapeutic recommendations is [70, 71]. Finally, the Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC) was launched in 2004 to build the foundation that underpins the advancement of personalized medicine as a viable solution to the challenges of efficacy, safety, and cost (www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org).

Concluding remarks

Pharmacogenomic studies over the last three decades have resulted in an overwhelming amount of evidence that genetic variation plays a major role in drug response variability. Over the last few years, GWAS provided some interesting findings mainly due to the large effects of these genes on drug response and toxicity. Over the next few years more comprehensive studies involving genome-wide associations and NGS are likely to dominate the field. Finally, the Achilles heel of this field is the implementation of findings into regular clinical practice. This being tackled by several large academic centers focused on the implementation of pharmacogenomics discoveries into routine clinical care to help guide clinical decisions. However, the true challenge will be in the adoption of these tests by mainstream physicians.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Pharmacogenomics of Anticancer Agents Research Group NIH/NIGMS UO1 GM61393, NIH/NCI Cancer Biology Training grant T32CA09594 (HEW), and support for AGM from The University of Chicago Cancer Research Foundation Women’s Board.

Role of funding source: The sponsor, played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weinshilboum RM, Sladek SL. Mercaptopurine pharmacogenetics: monogenic inheritance of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase activity. American journal of human genetics. 1980;32(5):651–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daly AK. Genome-wide association studies in pharmacogenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:241–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg2751. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey LB, et al. Rare versus common variants in pharmacogenetics: SLCO1B1 variation and methotrexate disposition. Genome research. 2012;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.129668.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kager L, Evans WE. Pharmacogenomics. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson TA, Manolio TA. How to interpret a genome-wide association study. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(11):1335–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkening S, et al. Is there still a need for candidate gene approaches in the era of genome-wide association studies? Genomics. 2009;93(5):415–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SH, et al. A genome-wide approach identifies that the aspartate metabolism pathway contributes to asparaginase sensitivity. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2011;25(1):66–74. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler HE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies variants associated with platinating agent susceptibility across populations. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2011 doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly AK, et al. HLA-B*5701 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin. Nature genetics. 2009;41(7):816–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadelius M, Alfirevic A. Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine: the plunge into next-generation sequencing. Genome Med. 2011;3(12):78. doi: 10.1186/gm294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunter C. Genomics: A picture worth 1000 Genomes. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11(12):814. doi: 10.1038/nrg2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatonetti NP, et al. An integrative method for scoring candidate genes from association studies: application to warfarin dosing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11(Suppl 9):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S9-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper GM, et al. A genome-wide scan for common genetic variants with a large influence on warfarin maintenance dose. Blood. 2008;112(4):1022–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abo R, et al. Merging pharmacometabolomics with pharmacogenomics using ‘1000 Genomes’ single-nucleotide polymorphism imputation: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor response pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2012;22(4):247–253. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835001c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilke RA, Dolan ME. Genetics and variable drug response. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(3):306–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuldiner AR, et al. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:849–858. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1232. (Copyright (C) 2012 American Chemical Society (ACS). All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein TE, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:753–764. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809329. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagreiya H, et al. Extending and evaluating a warfarin dosing algorithm that includes CYP4F2 and pooled rare variants of CYP2C9. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:407–413. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328338bac2. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein RS, et al. Warfarin genotyping reduces hospitalization rates results from the MM-WES (Medco-Mayo Warfarin Effectiveness study) Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55(25):2804–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gage BF, Lesko LJ. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin: regulatory, scientific, and clinical issues. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2008;25(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes and warfarin dosing. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;90(4):625–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon T, et al. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(4):363–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mega JL, et al. Cytochrome P-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. (Copyright (C) 2012 American Chemical Society (ACS). All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collet JP, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphism in young patients treated with clopidogrel after myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):309–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mega JL, et al. Dosing clopidogrel based on CYP2C19 genotype and the effect on platelet reactivity in patients with stable cardiovascular disease. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(20):2221–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pare G, et al. Effects of CYP2C19 genotype on outcomes of clopidogrel treatment. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1704–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008410. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tantry US, et al. First analysis of the relation between CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacodynamics in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel: the ONSET/OFFSET and RESPOND genotype studies. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(6):556–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge D, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7262):399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S. A new standard of care for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:257–64. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.49. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suppiah V, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1100–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka Y, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1105–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aparicio E, et al. IL28B SNP rs8099917 is strongly associated with pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy treatment failure in HCV/HIV-1 coinfected patients. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dayyeh BK, et al. IL28B alleles exert an additive dose effect when applied to HCV-HIV coinfected persons undergoing peginterferon and ribavirin therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welsh M, et al. Pharmacogenomic discovery using cell-based models. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:413–429. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001461. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wheeler HE, Dolan ME. Lymphoblastoid cell lines in pharmacogenomic discovery and clinical translation. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:55–70. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.121. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitra AK, et al. Genetic variants in cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase II are associated with its expression and cytarabine sensitivity in HapMap cell lines and in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2011;339(1):9–23. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang RS, et al. Platinum sensitivity-related germline polymorphism discovered via a cell-based approach and analysis of its association with outcome in ovarian cancer patients. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17(16):5490–500. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziliak D, et al. Germline polymorphisms discovered via a cell-based, genome-wide approach predict platinum response in head and neck cancers. Translational research: the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2011;157(5):265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shukla SJ, et al. Susceptibility loci involved in cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2008;18(3):253–62. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f5e605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen Y, et al. Chemotherapeutic-induced apoptosis: a phenotype for pharmacogenomics studies. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2011;21(8):476–88. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283481967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang RS, et al. Population differences in microRNA expression and biological implications. RNA biology. 2011;8(4):692–701. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.16029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsson P, et al. Discovery of regulatory elements in human ATP-binding cassette transporters through expression quantitative trait mapping. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2011 doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen Y, et al. An eQTL-based method identifies CTTN and ZMAT3 as pemetrexed susceptibility markers. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21(7):1470–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicolae DL, et al. Trait-associated SNPs are more likely to be eQTLs: annotation to enhance discovery from GWAS. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(4):e1000888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Donnell PH, Dolan ME. Cancer pharmacoethnicity: ethnic differences in susceptibility to the effects of chemotherapy. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(15):4806–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wheeler HE, et al. Genome-wide local ancestry approach identifies genes and variants associated with chemotherapeutic susceptibility in African Americans. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolan ME, et al. Heritability and linkage analysis of sensitivity to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer research. 2004;64(12):4353–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shukla SJ, et al. Whole-genome approach implicates CD44 in cellular resistance to carboplatin. Human genomics. 2009;3(2):128–42. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-2-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters EJ, et al. Pharmacogenomic characterization of US FDA-approved cytotoxic drugs. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(10):1407–15. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan XL, et al. Genetic variation predicting cisplatin cytotoxicity associated with overall survival in lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17(17):5801–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, et al. Evaluation of genetic variation contributing to differences in gene expression between populations. American journal of human genetics. 2008;82(3):631–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stranger BE, et al. Genome-wide associations of gene expression variation in humans. PLoS genetics. 2005;1(6):e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gamazon ER, et al. Exprtarget: an integrative approach to predicting human microRNA targets. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bell JT, et al. DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome biology. 2011;12(1):R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gamazon ER, et al. Chemotherapeutic drug susceptibility associated SNPs are enriched in expression quantitative trait loci. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(20):9287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001827107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(4):301–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ong FS, et al. Clinical utility of pharmacogenetic biomarkers in cardiovascular therapeutics: a challenge for clinical implementation. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:465–475. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.2. (Copyright (C) 2012 American Chemical Society (ACS). All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghaddar F, Cascorbi I, Zgheib NK. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenetics: a nonrepresentative explorative survey to participants of WorldPharma 2010. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:1051–9. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.42. (Copyright (C) 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin MA, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for hla-B genotype and abacavir dosing. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2012;91(4):734–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davis JC, et al. The microeconomics of personalized medicine: today’s challenge and tomorrow’s promise. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2009;8(4):279–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Relling MV, et al. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics: overcoming genetic exceptionalism. The lancet oncology. 2010;11(6):507–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reese ES, Mullins CD, BAL Cost-effectiveness of CYP2C19 genotype screening for selection of antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or prasugrel. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:323–32. doi: 10.1002/PHAR.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu AHB, Babic N, Yeo K-TJ. Implementation of pharmacogenomics into the clinical practice of therapeutics: issues for the clinician and the laboratorian. Pers Med. 2009;6:315–327. doi: 10.2217/pme.09.1. (Copyright (C) 2012 American Chemical Society (ACS). All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schubert C. Cancer drugs find a companion with new diagnostic tests. Nat Med. 2011;17:1157. doi: 10.1038/nm1011-1157. (Copyright (C) 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;89(3):464–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crews KR, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for codeine therapy in the context of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genotype. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2012;91(2):321–6. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Relling MV, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and thiopurine dosing. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;89(3):387–91. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scott SA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450-2C19 (CYP2C19) genotype and clopidogrel therapy. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;90(2):328–32. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swen JJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2008;83(5):781–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swen JJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte--an update of guidelines. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;89(5):662–73. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.John B, Lewis KR. Chromosome variability and geographic distribution in insects. Science. 1966;152(3723):711–21. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3723.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gottesman II, Shields J. Genetic theorizing and schizophrenia. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 1973;122(566):15–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.122.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bearden CE, Freimer NB. Endophenotypes for psychiatric disorders: ready for primetime? Trends in genetics: TIG. 2006;22(6):306–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gershon ES, Goldin LR. Clinical methods in psychiatric genetics. I. Robustness of genetic marker investigative strategies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1986;74(2):113–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb10594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Geus EJ. From genotype to EEG endophenotype: a route for post-genomic understanding of complex psychiatric disease? Genome medicine. 2010;2(9):63. doi: 10.1186/gm184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zou F, et al. Gene expression levels as endophenotypes in genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;74(6):480–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d07654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tomaszewski M, et al. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:859–866. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70601-6. (Copyright (C) 2012 American Chemical Society (ACS). All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maitland ML, et al. Initial assessment, surveillance, and management of blood pressure in patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(9):596–604. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maitland ML, et al. Ambulatory monitoring detects sorafenib-induced blood pressure elevations on the first day of treatment. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(19):6250–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yanagimachi M, et al. Influence of polymorphisms within the methotrexate pathway genes on the toxicity and efficacy of methotrexate in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2011;71(2):237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pirmohamed M, et al. The phenotype standardization project: improving pharmacogenetic studies of serious adverse drug reactions. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;89(6):784–5. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fernandez-Rozadilla C, et al. Pharmacogenomics in colorectal cancer: a genome-wide association study to predict toxicity after 5-fluorouracil or FOLFOX administration. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2012 doi: 10.1038/tpj.2012.2. (Copyright (C) 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aberg K, et al. Genome-wide association study of antipsychotic-induced QTc interval prolongation. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12:165–172. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.76. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tanaka Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identified ITPA/DDRGK1 variants reflecting thrombocytopenia in pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3507–3516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr249. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tan XL, et al. Genetic variation predicting cisplatin cytotoxicity associated with overall survival in lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:5801–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1133. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chantarangsu S, et al. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies Variations in 6p21.3 Associated With Nevirapine-Induced Rash. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:341–348. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir403. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ingle JN, et al. Genome-wide associations and functional genomic studies of musculoskeletal adverse events in women receiving aromatase inhibitors. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(31):4674–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang RS, et al. Platinum sensitivity-related germline polymorphism discovered via a cell-based approach and analysis of its association with outcome in ovarian cancer patients. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:5490–500. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0724. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tantisira KG, et al. Genome-wide Association Identifies the T Gene as a Novel Asthma Pharmacogenetic Locus. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2061OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tantisira KG, et al. Genomewide association between GLCCI1 and response to glucocorticoid therapy in asthma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(13):1173–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ozeki T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies HLA-A*3101 allele as a genetic risk factor for carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1034–1041. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq537. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Innocenti F, et al. A genome-wide association study of overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine in CALGB 80303. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18(2):577–84. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Drago A, Crisafulli C, Serretti A. The genetics of antipsychotic induced tremors: a genome-wide pathway analysis on the STEP-BD SCP sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:975–86. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31245. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Garriock HA, et al. A genomewide association study of citalopram response in major depressive disorder. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(2):133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Srinivasan Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of epirubicin-induced leukopenia in Japanese patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21:552–558. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328348e48f. (Copyright C 2012 American Chemical Society ACS. All Rights Reserved.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McCormack M, et al. Genome-wide mapping for clinically relevant predictors of lamotrigine- and phenytoin-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:399–405. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.165. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aslibekyan S, et al. A genome-wide association study of inflammatory biomarker changes in response to fenofibrate treatment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drug and Diet Network. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2012;22:191–7. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834fdd41. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tohkin M, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for allopurinol-related Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japanese patients. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2011 doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.41. (Copyright (C) 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Singer JB, et al. A genome-wide study identifies HLA alleles associated with lumiracoxib-related liver injury. Nat Genet. 2010;42:711–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.632. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim JH, et al. Genome-wide and follow-up studies identify CEP68 gene variants associated with risk of aspirin-intolerant asthma. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013818. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chung CM, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new loci for ACE activity: potential implications for response to ACE inhibitor. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2010;10:537–44. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.70. (Copyright C 2012 U.S. National Library of Medicine.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lucena MI, et al. Susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury is influenced by multiple HLA class I and II alleles. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):338–47. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McCormack M, et al. HLA-A*3101 and carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions in Europeans. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(12):1134–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nicoletti P, et al. Genomewide pharmacogenetics of bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw: the role of RBMS3. The oncologist. 2012;17(2):279–87. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]