Abstract

Despite significant advances in understanding the role of benzodiazepine (BZ)-sensitive populations of GABAA receptors, containing the α1, α2, α3 or α5 subunit, factual substrates of BZ-induced learning and memory deficits are not yet fully elucidated. It was shown that α1-subunit affinity-selective antagonist β-CCt almost completely abolished spatial learning deficits induced by diazepam (DZP) in the Morris water maze. We examined a novel, highly (105 fold) α1-subunit selective ligand - WYS8 (0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), on its own and in combination with the non-selective agonist DZP (2 mg/kg) or β-CCt (5 mg/kg) in the water maze in rats. The in vitro efficacy study revealed that WYS8 acts as α1-subtype selective weak partial positive modulator (40% potentiation at 100 nM). Measurement of concentrations of WYS8 and DZP in rat serum and brain tissues suggested that they did not substantially cross-influence the respective disposition. In the water maze, DZP impaired spatial learning (acquisition trials) and memory (probe trial). WYS8 caused no effect per se, did not affect the overall influence of DZP on the water-maze performance and was devoid of any activity in this task when combined with β-CCt. Nonetheless, an additional analysis of the latency to reach the platform and the total distance swam suggested that WYS8 addition attenuated the run-down of the spatial impairment induced by DZP at the end of acquisition trials. These results demonstrate a clear difference in the influence of an α1 subtype-selective antagonist and a partial agonist on the effects of DZP on the water-maze acquisition.

Keywords: GABAA subtype selective ligand, diazepam, water maze, two electrode voltage clamp

1. INTRODUCTION

The emergence of benzodiazepines (BZs) in the 1960s, exemplified by diazepam (DZP), ushered in the new era in the treatment of anxiety-related disorders (Argyropoulos and Nutt, 1999). However, in modern clinical practice BZs are prescribed with considerable caution and they are often replaced with other classes of psychotropic drugs (Davidson et al., 2010). Such a restricted use can be related to their suboptimal safety profile which includes sedation, daytime drowsiness, anterograde amnesia, ataxia, dependence liability and tolerance. Despite these drawbacks, they are still one of the most prescribed medicines for the treatment of insomnia and short term anxiety (Cloos and Ferreira, 2009). All standard BZs bind with comparable affinity to GABAA receptors which contain the α1, α2, α3 or α5 subunit in addition to a β and the γ2 subunit, arranged as a pentameric unit with an α:β:γ subunit stoichiometry of 2:2:1 (Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). A growing body of evidence supports interrelationships among particular α subunits and distinct effects of BZs, both wanted and unwanted (Sieghart, 2006). Thus, sedation, motor incapacitation, anterograde amnesia and, in part, anticonvulsant effect are attributed to GABAA receptor population containing the α1 subunit, whereas anxiolytic and muscle relaxant effects are most likely mediated by α2 and, under conditions of higher receptor occupancy, α3 GABAA receptors (D’Hulst et al., 2009; Rudolph and Möhler, 2006). Numerous studies confirm that the population of GABAA receptors containing α5 subunit is involved in BZs’ influence on memory formation (Atack, 2011). Although present in approximately 5% of total brain GABAA receptors, this subtype is included in approximately 25% of receptors within hippocampus (Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Sur et al., 1999) where it plays an important role in tonic inhibition of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Caraiscos et al., 2004).

In contrast to the more restricted distribution of the α5 subtype, the most abundant α1-containing GABAA receptors are absent in only a few brain regions (e.g. granule cell layer of the olfactory bulb, reticular nucleus of the thalamus, spinal cord motoneurons) (Fritschy and Möhler, 1995; Pirker et al., 2000). Hence, it is not unexpected that these GABAA receptors may also be involved in mnemonic processes (Rudolph et al., 1999). Our recent study corroborated this suggestion by showing that effects on the water maze performance caused by DZP can be antagonized by a high affinity neutral modulator selective for α1 GABAA receptors such as β-CCt (Savić et al., 2009). Moreover, our further study with novel ligands selective for α subunits other than α1 subtype suggested that a substantial amount of activity at α1 GABAA receptors is needed if spatial learning and memory incapacitation in the water maze is to be induced by positive allosteric modulation at the BZ site (Savić et al., 2010).

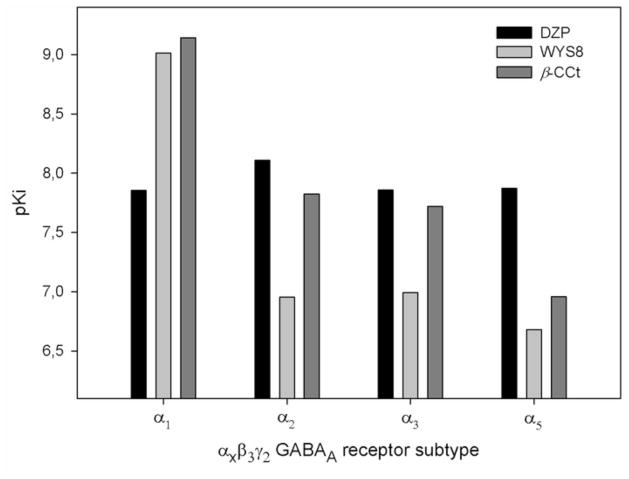

In this study we described WYS8 (8-ethynyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate-t-butyl ester), a close congener of β-CCt (t-butyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate). The binding data for WYS8, in parallel with those for DZP and β-CCt, are presented in Figure 1 (redrawn according to Yin et al., 2010). While DZP binds with similar affinity to all four BZ-sensitive subtypes of recombinant human GABAA receptors, WYS8 demonstrated an approximate 105-fold selectivity for GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit. In fact, although both β-CCt and WYS8 bind to α1 GABAA receptors with high, sub-nanomolar affinities, the latter is one of the most α1 subtype selective ligands reported to date (Yin et al., 2010). In the present study, we examined the in vitro efficacy of WYS8 and also tested it on its own and in combination with DZP or β-CCt in the Morris water maze, one of the most utilized tools for assessing hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in rats (D’Hooge and De Deyn, 2001).

Figure 1.

Binding affinity at αxβ3γ2 GABAA/BZ site subtypes. Measurements were made in duplicate. Affinity data for WYS8 and β-CCt are taken from Yin et al. (2010).

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Drugs

The novel compound WYS8 (8-ethynyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate-t-butyl ester) and β-CCt (t-butyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate), the preferential α1-subunit selective antagonist, were synthesized at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee. The standard benzodiazepine DZP was obtained from Galenika (Belgrade, Serbia).

Two electrode voltage clamp

cDNAs of rat GABAA receptor subunits were used for generating the respective mRNA’s that were then injected into Xenopus laevis oocytes (Nasco, WI) as described previously (Ramerstorfer et al., 2010). For electrophysiological recordings, oocytes were placed on a nylon-grid in a bath of Xenopus Ringer solution (XR, containing 90 mM NaCl, 5 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM KCl and 1 mM CaCl2). The oocytes were constantly washed by a flow of 6 ml/min XR which could be switched to XR containing GABA and/or drugs. Drugs were diluted into XR from DMSO-solutions resulting in a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO perfusing the oocytes. Drugs were preapplied for 30 sec before the addition of GABA, which was coapplied with the drugs until a peak response was observed. Between two applications, oocytes were washed in XR for up to 15 min to ensure full recovery from desensitization. For current measurements, the oocytes were impaled with two microelectrodes (2–3 mΩ) which were filled with 2 mM KCl. All recordings were performed at room temperature at a holding potential of −60 mV using a Warner OC-725C two-electrode voltage clamp (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Data were digitised, recorded and measured using a Digidata 1322A data acquisition system (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Results of concentration response experiments were graphed using GraphPad Prism 4.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data were graphed as mean ± SEM of three to six oocytes from at least two batches.

Quantification in rat serum and brain tissue

Twenty-four Wistar rats (Military Farm, Belgrade, Serbia), weighted 200–240 g, were divided into six groups and subjected to repeated intraperitoneal administration of solvent, WYS8 (10 mg/kg) and/or DZP (2 mg/kg) once daily during 4 days, as shown in Table 1. WYS8 and DZP were dissolved/suspended with the aid of sonication in a solvent containing 85% distilled water, 14% propylene glycol, and 1% Tween 80. The concentrations of WYS8 and DZP in serum and brain were measured 20 min after application of the last injection. Following decapitation, blood samples were collected from the carotid arteries, then centrifuged at 5000×g for 15 min and the supernatant (serum) was subjected to the HPLC analysis. Brains were also rapidly removed, rinsed with saline, measured (average mass: 1.53 g) and homogenized at 16000 rpm for 2 min by a rotor-stator blender (T 25 digital Ultra-Turrax, IKA, Germany) in 2 ml of methanol. The final volume was adjusted to 5 ml with methanol and after centrifugation (9000×g for 15 min), aliquots were subjected to the LC-MS analytical method.

Table 1.

Analysis of WYS8 and DZP in rat serum and brain samples. Each value is the mean ± SD of 4 samples. SOL = solvent; WYS8 = WYS8 at 10 mg/kg body weight; DZP = DZP at 2 mg/kg body weight; nqd = no quantitative data.

| WYS8 | DZP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | 3 days | SOL | WYS8 | SOL | WYS8 + DZP | SOL | DZP | SOL | WYS8 + DZP |

| 4. day | WYS8 | WYS8 | WYS8 + DZP | WYS8 + DZP | DZP | DZP | WYS8 + DZP | WYS8 + DZP | |

| concentration (nmol/L) | Serum | 171.26 ± 93.85 | 179.24 ± 31.56 | 147.46 ± 45.27 | 177.77 ± 97.04 | 151.37 ± 82.91 | 284.66 ± 140.24 | 298.98 ± 173.86 | 243.61 ± 21.12 |

| Brain | 91.36 ± 29.36 | 89.94 ± 24.60 | 64.77 ± 15.63 | 72.33 ± 16.27 | nqd | nqd | nqd | nqd | |

Concentrations of WYS8 and DZP in serum and brain tissue were determined using a Waters Alliance 2695, Mass Lynx, Waters ZQ 2000 quadrupole analyzer utilizing the electrospray ionization interface (ESI-MS) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), where data were collected in selected ion monitoring (SIM) at m/z 237 in full-scan ES+ mode or at m/z 100–400. The limits of quantification for both, WYS8 and DZP, were 1 μg/L for serum samples, and 10 μg/L for brain tissue samples. The sample pre-treatment procedure was carried out by means of solid-phase extraction (SPE) on Oasis® HLB cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), preconditioned with methanol and water. The samples (acidified serum or diluted acidified supernatant of brain tissue homogenate) were loaded and cartridges washed with 1 ml of 5% methanol. The cartridges were dried under vacuum and compounds of interest eluted with 1 ml of methanol. After evaporation, residues were reconstituted in 1 ml of the mobile phase: 5 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.5): acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid = 45% : 55% isocrate; and injected onto the LC system. Separation was carried out in XTerra RP18 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

Behavioral experiments

Experiments were carried out on male Wistar rats (Military Farm, Belgrade, Serbia), weighing 220–250 g (n=8/group). All procedures in the study conformed to EEC Directive 86/609 and were approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation of the Faculty of Pharmacy in Belgrade. The rats were housed in transparent plastic cages, six animals per cage, and had free access to food pellets and tap water. The temperature of the animal room was 22±1°C, the relative humidity 40–70%, the illumination 120 lux, and the 12/12 h light/dark period (light on at 6:00 h). All handling and testing took place during the light phase of the diurnal cycle. In the present behavioral study, we used 12 treatment groups altogether: solvent, DZP (2 mg/kg), WYS8 (0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), β-CCt (5 mg/kg), DZP (2 mg/kg) + WYS8 (0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg) and β-CCt (5 mg/kg) + WYS8 (0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg). All ligands were dissolved/suspended with the aid of sonication in the same solvent as given for the quantification studies and were administered intraperitoneally. The first treatment indicated in combination was administered into the lower right quadrant of the peritoneum, and the second treatment immediately afterwards into the lower left quadrant of the peritoneum. The rats’ behavior in the water maze was monitored via a ceiling-mounted network camera which relayed information to a video tracking system (ANY-maze Video Tracking System software, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) and the tracking was adjusted to accommodate a white rat on a black background.

Behavior in the Morris water maze

The water maze consisted of a cylindrical pool (diameter: 200 cm, height: 60 cm), with a uniform black inner surface. The pool was filled to a height of 30 cm with 23°C (±1°C) water. The escape rectangular platform made of black plastic (15×10 cm) was submerged 2 cm below the water surface. The platform was made invisible to rats by having it painted the same color as the pool wall (Terry, 2001). There were many distal cues in the testing room (doors, pipes on the walls and the ceiling, and cupboards). An indirect illumination in the experimental room was provided by white neon tubes fixed on the walls near the pool. The rats received the appropriate treatment 20 min before a swimming block, each day for 5 consecutive days of spatial acquisition. Each block consisted of 4 trials, lasting a maximum time of 120 s, the intertrial interval being 60 s. For each trial the rat was placed in the water facing the pool at one of four pseudorandomly determined starting positions. Each rat was left to swim in the water tank until it found the platform hidden in the center of the NE quadrant. Bearing in mind the location of platform, the four distal start locations were chosen: S, W, NW and SE. Once the rat found and mounted the platform, it was permitted to remain on it for at least 15 s. The rat was guided to the platform by the experimenter if it did not locate the escape platform within 120 s. After that, it was removed from the platform and put into a cage to rest. Twenty-four hours after the last acquisition day, the rats were subjected to a probe trial for 60 s, without the escape platform and any pre-treatment (Vorhees and Williams, 2006). The animals started the trial from the novel, most distant SW location. The object of the probe trial was to determine if the animal remembered where the platform had been located during the acquisition phase.

The tracking software virtually divided the pool into four quadrants, three concentric annuli and a target region consisting of the intersection of the platform quadrant and the platform (middle) annulus, as graphically represented in Savić et al. (2009). The central annulus was set up to 10% of the whole area; the platform annulus equaled 40%, whereas the area of the peripheral annulus was 50% of the whole.

Dependent variables chosen for tracking during the acquisition trials were: the latency to find the platform (time from start to goal), the path efficiency (the ratio of the shortest possible path length to actual path length) and the total distance travelled (path length). All these indices are, to a lesser or greater degree, related to the goal-directed behavior i.e. spatial learning (Vorhees and Williams, 2006). In order to assess the declarative component of memory, we calculated the percentage of distance swam in the target region in relation to the distance travelled in the quadrant where the platform was situated (NE). As regards the probe trial, time spent in the target region and the distance swam in the peripheral ring were the selected parameters. Thigmotaxis phenomenon (wall hanging i.e. the tendency to swim or float near the pool wall) represents an important factor which accounts for much of the variance in the water-maze performance, and normally weakens during consecutive trials (Vorhees and Williams, 2006). The loss of thigmotaxis is related to the procedural component of acquisition so the two variables tracked during the probe trial may be seen as a measure of procedural learning.

Statistical analysis

All numerical data presented in the figures were given as the mean ± SEM. For electrophysiological data the one-sample Student’s t-test on percent values was used. Data from the kinetic study was analyzed using two-way ANOVA. The factors were concentrations of WYS8, and, in a separate analysis, of DZP (both with two levels, when administered on their own and in combination) and duration of treatment (two levels: single and repeated administration). For each training day and parameter measured in the water maze the mean value was calculated for each rat (total data/total number of trials). The effects of WYS8 and DZP (or WYS8 and β-CCt) in the water maze were analyzed by a three-factor general linear model with repeated-measures (GLM RM). Two between-subjects factors were WYS8 (four levels) and DZP or β-CCt (both with two levels). There were five levels of the within-subjects factor DAY (i.e. repeated measures over the 5 training days). Mauchly’s test was used to evaluate the sphericity of within-subject effects and, if significant, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Significant interaction between DAY and DZP was further analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with repeated-measures (DZP as between- and DAY as within-subjects factor). In order to fully investigate the influence of both ligands on the water maze performance during five days of acquisition, we additionally used a two-way ANOVA (WYS8 x DZP) both overall (dependant variable consisted of the means of all average values calculated for each rat for each day) and separately for each day (dependant variable consisted of the means for each rat for the respective day).

All post hoc comparisons were performed using Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test. Statistical analyses were performed with PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Sigma Plot 11 (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA, USA). Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p was less than 0.05.

3. RESULTS

In vitro efficacy

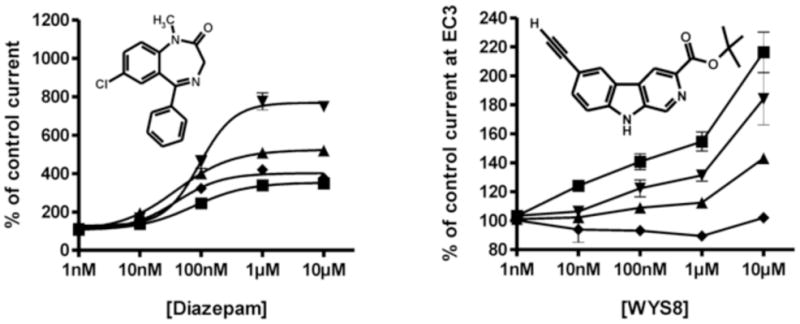

The in vitro concentration-effect curves for WYS8 and DZP as a reference are presented in Figure 2, together with explicit data on percent potentiation of a within- and between- day stable EC3 GABA response at rat recombinant GABAA receptors. WYS8 exerted weak positive modulation (partial agonism) at α1-containing GABAA receptors already at 10 nM, while at α2 GABAA and α3 GABAA receptors it behaved as a partially effective positive modulator at concentrations of 100 nM and more. At α5 GABAA receptors, only a high concentration (1 μM) of WYS8 resulted in a significant, though relatively small negative modulation. DZP exerted substantial potentiation of an EC3 GABA response at all four receptor subtypes already at 10 nM concentration.

Figure 2.

Concentration-effect curves for DZP and WYS8 on α1β3γ2 (■), α2β3γ2 (▲), α3β3γ2 (▼), and α5β3γ2 (◆) GABAA receptors, using an EC3 GABA concentration. Data points represent means ± SEM from three to six oocytes from ≥ 2 batches. 10 nM of WYS8 resulted in a significant 124±3% of control current for α1β3γ2 receptors. At this concentration, there was no significant stimulation of GABA-induced current in the other receptor subtypes investigated. As a comparison, a concentration of 10 nM of DZP resulted in 136 ± 3%, 193 ± 5%, 167 ± 8%, and 160 ± 2% of control current in α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, α3β3γ2, and α5β3γ2 GABAA receptors, respectively. A concentration of 100 nM of WYS8 resulted in 141±5%, 109±2%, 126±7%, and non-significant changes relative to control current in α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, α3β3γ2, and α5β3γ2 GABAA receptors, respectively. A concentration of 100 nM of DZP resulted in 246 ± 10%, 400 ± 22%, 461 ± 34%, and 322 ± 7% of control current in α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, α3β3γ2, and α5β3γ2 GABAA receptors, respectively. All values given were significantly different from the respective control currents (p < 0.01, Student’s t-test).

Quantification in rat serum and brain tissue

The molar concentrations of WYS8 and DZP in the serum and brain after single or repeated intraperitoneal doses of 10 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg, respectively, are presented in Table 1. Two-way ANOVAs did not reveal that WYS8 and DZP cross-influenced the respective kinetics in serum, either after one or after four days of treatment. In the analysis with the results of WYS8, the F values of factors WYS8, treatment duration and their interaction were: F(1,12) = 0.120, p = 0.735; F(1,12) = 0.276, p = 0.609 and F(1,12) = 0.0937, p = 0.765, respectively. For DZP data, the F values of factors DZP, treatment duration and their interaction were: F(1,12) = 0.794, p = 0.390; F(1,12) = 0.424, p = 0.527 and F(1,12) = 2.488, p = 0.141, respectively. In regard of brain samples, concomitant administration of DZP did not affect the concentration of WYS8 in either of two treatment regimens. The F values of factors WYS8, treatment duration and their interaction were: F(1,12) = 3.955, p = 0.070; F(1,12) = 0.076, p = 0.787 and F(1,12) = 0.163, p = 0.693, respectively. Due to technical problems, we did not collect quantitative data of DZP in brain tissues; however, semi-quantitative estimations of concentrations (the range of concentrations was 50–300 nmol/L) did not reveal any hint of possible alteration of DZP disposition due to presence of WYS8.

Morris Water Maze

Latency

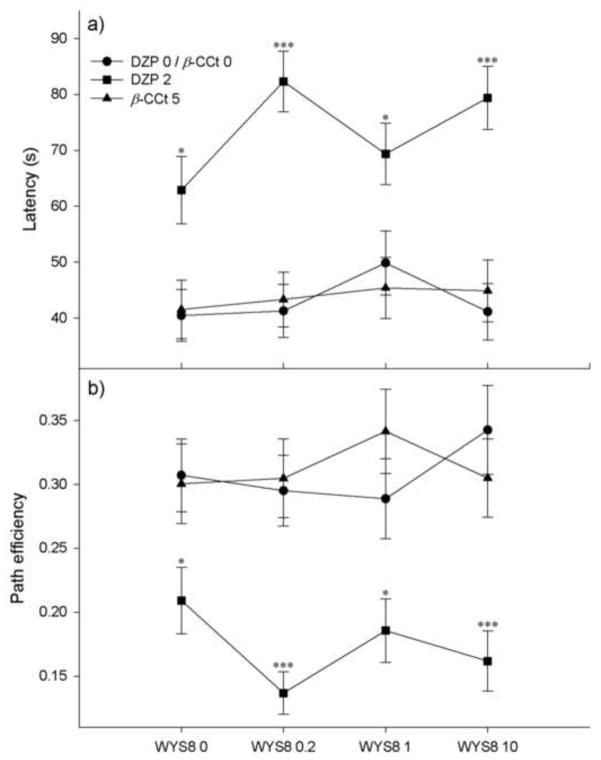

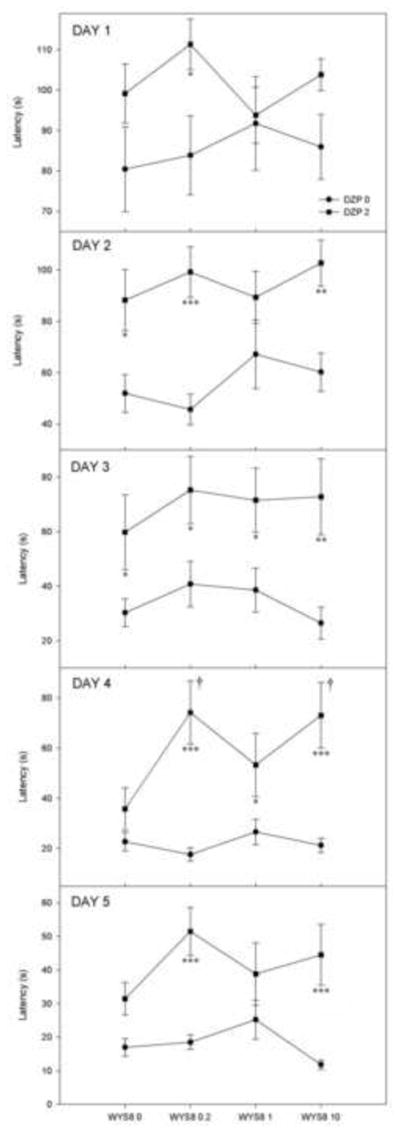

A GLM RM procedure applied on the analysis of the influences on the latency to reach the platform during five days of acquisition (Fig. 3a) has shown a non-significant three-way interaction (WYS8 x DZP x DAY, F(8.786,164.003) = 0.778, p = 0.634). There was a significant effect of DZP (F(1,56) = 45.799, p<0.001) and DAY (F(2.929,164.003) = 117.940, p<0.001), but not of WYS8 (F(3,56) = 1.026, p = 0.388). In addition, only the interaction between DZP and DAY was significant (F(2.929,164.003) = 4.147, p=0.008). A two-way RM ANOVA (DZP x DAY) followed by post hoc SNK test revealed that DZP, dosed at 2 mg/kg, was highly significant within each of five days of acquisition. When factor DZP was replaced with β-CCt (Fig. 3a) the three-factor GLM RM revealed that three-way interaction was also insignificant (WYS8 x β-CCt x DAY, F(9.020,168.376) = 1.209, p = 0.293), while the only statistically significant effect was that of factor DAY (F(3.007,168.376) = 121.966, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

The effects of WYS8 (0, 0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), in the absence (DZP 0/β-CCt 0, ●) and the presence of 2 mg/kg DZP (DZP 2, ■), or 5 mg/kg β-CCt (▲), on the latency to reach the escape platform (a) and the path efficiency (b) during five days of acquisition. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 compared to DZP 0 within appropriate level of WYS8;. Each data point represents the mean of all average values calculated for each rat for each day. Number of animals per each treatment group was 8.

An overall two-way ANOVA (WYS8 x DZP) confirmed that the addition of WYS8 to DZP did not influence the latency to reach the platform. On the other hand, when a two-way ANOVA (WYS8 x DZP) was applied on each training day (Fig. 4), it appeared that rats treated with DZP alone had longer latencies compared with those treated with solvent during the second and third, but not the fourth and fifth day of acquisition (the respective p values were 0.01, 0.05, 0.295 and 0.096). However, on the fourth and fifth day, the animals treated with DZP and WYS8 showed longer latencies compared with those treated with the respective dose of WYS8 (on the fourth day, for all three doses of WYS8, while on the fifth day, for the doses of 0.2 and 10 mg/kg). Moreover, on the fourth day, the rats treated with DZP and WYS8 at doses of 0.2 and 10 mg/kg exhibited significantly longer latencies than those treated with DZP alone (p=0.016 and p=0.011, respectively).

Figure 4.

The effects of WYS8 (0, 0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), in the absence (●) and the presence of 2 mg/kg DZP (■) on the latency to reach the escape platform during each of five acquisition days. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 and *** p<0.001 compared to DZP 0 within appropriate level of WYS8; † p<0.05 compared to WYS8 0+DZP 2 group.

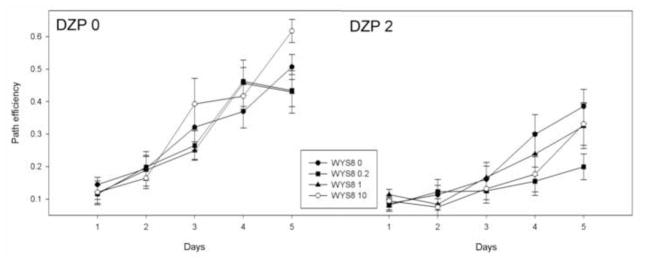

Path efficiency

For the path efficiency parameter (Fig. 3b), a GLM RM analysis has shown a non-significant three-way interaction (WYS8 x DZP x DAY, F(10.244,191.227) = 1.265, p = 0.251). There was a significant effect of DZP (F(1,56) = 45.905, p<0.001) and DAY (F(3.415,191.227) = 78.149, p<0.001), while not of WYS8 (F(3,56) = 0.892, p = 0.451). Once more, the only statistically significant interaction was DZP x DAY (F(3.415,191.227) = 7.100, p<0.001). When this interaction was analyzed by two-way RM ANOVA it has been shown that the rats treated with DZP had significantly lower path efficiencies than solvent-treated controls from day two onwards. When factor DZP was replaced with β-CCt (Fig. 3b) the three-factor GLM RM revealed that three-way interaction was also insignificant (WYS8 x β-CCt x DAY, F(12,224) = 1.041, p = 0.412), while the only statistically significant effect was that of factor DAY (F(4,224) = 91.978, p<0.001).

An overall two-way ANOVA (WYS8 x DZP) showed that the influence of DZP on the path efficiency was significant within all four WYS8 levels. There was no statistically significant difference between various levels of WYS8 within the same level of DZP, assessed both by an overall two-way ANOVA and that applied on each training day (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The effects of WYS8 (0, 0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), in the absence (DZP 0) and the presence of 2 mg/kg DZP (DZP 2) on the path efficiency during five days of acquisition.

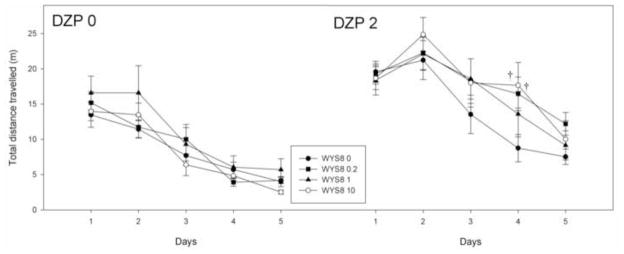

Total distance

Regarding the total distance travelled (swam) during the acquisition trials, a GLM RM analysis has shown a non-significant three-way interaction (WYS8 x DZP x DAY, F(8.684,162.101) = 1.023, p = 0.423). There was a significant effect of DZP (F(1,56) = 53.397, p<0.001), DAY (F(2.895,162.101) = 65.902, p<0.001), while not of WYS8 (F(3,56) = 0.965, p = 0.416). Once more, the only statistically significant interaction was DZP x DAY (F(2.895,162.101) = 4.064, p=0.009). When this interaction was analyzed by two-way RM ANOVA it has been shown that the rats treated with DZP had significantly longer distances than solvent-treated controls during all five days.

An overall two-way ANOVA (WYS8 x DZP) showed that the influence of DZP on the total distance travelled was significant within all four WYS8 levels. There was no statistically significant difference between various levels of WYS8 within the same level of DZP, assessed both by an overall two-way ANOVA and that applied on training days (Fig. 6), with one exception: on the fourth day, the rats treated with DZP and WYS8 at doses of 0.2 and 10 mg/kg exhibited significantly longer distances than those treated with DZP alone (p=0.030 and p=0.019, respectively).

Figure 6.

The effects of WYS8 (0, 0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), in the absence (DZP 0) and the presence of 2 mg/kg DZP (DZP 2) on the total distance travelled during five days of acquisition. † p<0.05 compared to WYS8 0+DZP 2 group.

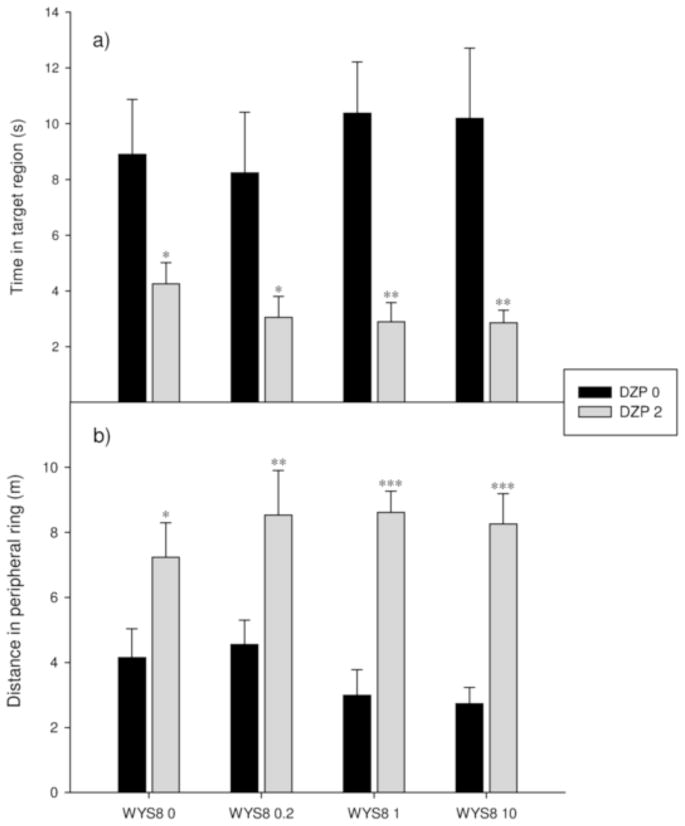

Probe trial

The two-way ANOVA for the parameters measured during the probe trial (the time spent in the target region and the distance swam in the peripheral ring) showed significant effect of only one factor – DZP (F(1,56) = 30.025, p<0.001 and F(1,56) = 50.881, p<0.001, respectively). Post hoc analysis revealed that rats treated with DZP, both on itself and in combination with WYS8, spent comparably small amount of time in the target region and exhibited strong thigmotaxic effect, measured through the increase of the distance swam in the peripheral ring (Fig. 7a and 7b, respectively).

Figure 7.

The effects of WYS8 (0, 0.2, 1 and 10 mg/kg), in the absence (DZP 0) and the presence of 2 mg/kg DZP (DZP 2) on the time spent in the target region (a) and the distance swam in the peripheral ring (b) during the probe trial. *, ** and ***, p<0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively, when two levels of factor DZP were compared within the respective level of WYS8.

4. DISCUSSION

The Morris water maze, while simple at first glance, is a challenging task for rodents that employs a variety of sophisticated mnemonic processes (Terry, 2001). Using this behavioral paradigm, we have already shown that DZP’s acquisition impairing effects could be almost completely prevented by β-CCt, an antagonist highly selective for α1 GABAA receptors (Savić et al., 2009). Here, we report on similarly designed studies with WYS8, a close congener of β-CCt possessing even higher subtype selectivity for α1 GABAA receptors (Yin et al., 2010). The presented efficacy results show that WYS8 acts as a weak partial positive modulator selective for α1 GABAA receptors. Thus, although the flatness of the efficacy curves precludes calculation of the exact EC50 values, an approximately 10–100-fold higher concentration of WYS8 is needed to generate an equivalent effect at α3 receptors in comparison to α1 GABAA receptors at lower concentrations (around 10–100 nM), which corresponds well with the 105-fold ratio in their binding affinities (Yin et al., 2010). Moreover, although it is clear that total brain concentration cannot predict the receptor occupancy (Watson et al., 2009), the concentration data obtained with the highest behaviorally tested dose of WYS8 (10 mg/kg) suggest that this ligand did not appreciably bind to GABAA receptors other than those containing the α1 subtype. Namely, the ratios of the total brain concentration of WYS8 (<100 nM) to its in vitro affinities for α2, α3, and α5 GABAA receptors (Ki values of 111, 102 and 208 nM, respectively; Yin et al., 2010) are consistently lower than 1. It is known that such low ratios are connected with receptor occupancy far below 50% at the benzodiazepine binding site (Scott-Stevens et al., 2005)..

As expected, our results demonstrate that DZP (2 mg/kg) impaired the task-acquisition in the water maze: it prolonged the latency to find the hidden platform, decreased the path efficiency and increased the distance swam during five days of acquisition. The fact that BZs, notably DZP, produce a profound anterograde amnesia in the Morris water maze is well established (McNamara and Skelton, 1991; Savić et al., 2009). The cued water maze task employs both procedural (striatal) and declarative (hippocampal) memory with the emphasis on the latter component (Izquierdo et al., 2006). Despite the difficulties in segregating these components, our previous results suggested that DZP impairs the acquisition of both procedural (as assessed through parameters such as the time spent in the peripheral ring) and declarative memory (as assessed with, for example, the path efficiency) (Savić et al., 2009).

Combining partial and full agonists is not a new concept in the field of behavioral neuropharmacology of BZs. As an example, the non-selective partial agonist bretazenil antagonized the effects of full BZ site agonists on motor behavior (Smith et al., 2004), defensive behaviors (Griebel et al., 1999) or the response sequence acquisition and retention (Auta et al., 1995). On its own, the novel α1-subtype selective partial agonist WYS8 had no substantial effect on Morris water-maze performance, in a manner similar to its close congener, β-CCt (Savić et al, 2009; the present results). However, while β-CCt had almost completely abolished spatial learning deficits induced by DZP in the water maze (Savić et al, 2009), the addition of WYS8 to DZP did not generally affect the BZ’s actions, demonstrating a profound difference in the influence of an α1 subtype-selective antagonist and a partial agonist on the effects of DZP on the water-maze acquisition.

The results of additional analysis of the latency and the total distance travelled suggested that WYS8 may even have enhanced the impairing effect of DZP during the acquisition days; despite some hints, this trend was not dependent on the dose of WYS8. Actually, the latency results revealed a reduction of the impairing effects of DZP during the last two days of acquisition. A phenomenon of rapid tolerance after three (File and Fernandes, 1994), or only one dose (Khanna et al., 1998) of a BZ has been described for some behavioral outputs. However, McNamara and Skelton (1997) found that tolerance to amnesic effects in the water maze did not develop even after 15 days of DZP pretreatment, demonstrating that the present results cannot be reflective of a genuine tolerance. It is generally believed that tolerance-like changes observable during repeated treatment with BZs could be related to an alteration in the numbers of GABAA receptors rather than to their kinetics (Bateson, 2002). As WYS8 and DZP did not substantially affect the respective pharmacokinetics, the present results indirectly suggest that α1 GABAA receptors are involved in processes related to the attenuation of effects of BZs on cognitive function. It was found that after only 7 days of treatment with flurazepam, binding of radiolabelled zolpidem was decreased by 23% in the cerebellum and by 14% in the hippocampus, suggesting a rapid decrease of α1 GABAA receptors in rat brain (Wu et al., 1995). The persistence of the water-maze impairment effected by DZP+WYS8 combination could be associated with reduction of the overall potentiation of GABAergic transmission at α1 GABAA receptors and thus their slower downregulation, but this hypothesis needs to be addressed in further studies.

The analysis of parameters measured during the probe trial indicated that rats treated with either DZP alone or in combination with WYS8 showed impaired spatial performance. On the contrary, β-CCt had at least partially prevented spatial memory deficits induced by DZP, as evaluated in the probe trial (Savić et al, 2009). As both the time in target region and distance in peripheral ring were affected in all animals treated with DZP, irrespective of the presence of WYS8, the impairment of the procedural component of the memory task (assessed through activity in periphery) may substantially contribute to the overall behavior of these animals in the probe trial. Hence, the rats seemingly adapted to the deteriorating effect of DZP during the final acquisition trials were nevertheless unable to recollect the original position of the platform. Probably, this was due to profound influence of treatment on the swimming strategy in probe trial (Cain, 1998) and differences in the very nature of the probe vs. acquisition trial (Vorhees and Williams, 2006).

In conclusion, these results corroborate our previous findings (Savić et al. 2009, 2010) that GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit play a major role in mediating effects of the BZs site modulation on the water maze behavior. While the spatial learning deficits induced by DZP were amenable to prevention by an α1-subunit selective antagonist, a weak partial agonist at the same receptors was devoid of such an effect. Therefore, it is clear that the subtle changes in the degree of α1 GABAA receptor activation may substantially affect the spatial learning performance of rats.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source

Funding for this work was provided in part by The Ministry of Science, R. Serbia – Grant No. 175076 (MMS) and by NIMH 46851 (JMC). Also, the work was supported by the Research Growth Initiative of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. The funding bodies had no further role in study design, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

ML Van Linn and W Yin synthesized the ligands. S Joksimović, J Divljaković, Z Varagic, G Brajković, MM Milinković and T Timić carried out the experiments and performed the data analysis. W Sieghart, JM Cook and MM Savić, supervised the work. S Joksimović and MM Savić wrote a first draft of the paper and contributed to the final version. W Sieghart and JM Cook improved the manuscript by valuable suggestions. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they do not have any conflicts of interest, disclosure, financial and material support in relation to this study. Funding sources are declared under “Role of the funding source”.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Argyropoulos SV, Nutt DJ. The use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and other disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9 (Suppl 6):S407–S412. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(99)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack JR. GABA(A) Receptor Subtype-Selective Modulators. II α5-Selective Inverse Agonists for Cognition Enhancement. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:1203–1214. doi: 10.2174/156802611795371314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auta J, Faust WB, Lambert P, Guidotti A, Costa E, Moerschbaecher JM. Comparison of the effects of full and partial allosteric modulators of GABA(A) receptors on complex behavioral processes in monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:323–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson AN. Basic pharmacologic mechanisms involved in benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:5–21. doi: 10.2174/1381612023396681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain DP. Testing the NMDA, long-term potentiation, and cholinergic hypotheses of spatial learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You-Ten KE, Cheng VY, Belelli D, Newell JG, et al. Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3662–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307231101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos JM, Ferreira V. Current use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:90–95. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831a473d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Zhang W, Connor KM, Ji J, Jobson K, Lecrubier Y, McFarlane AC, et al. A psychopharmacological treatment algorithm for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:3–26. doi: 10.1177/1359786810383890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hulst C, Atack JR, Kooy RF. The complexity of the GABAA receptor shapes unique pharmacological profiles. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Fernandes C. Dizocilpine prevents the development of tolerance to the sedative effects of diazepam in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:823–826. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Möhler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel G, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Study of the modulatory activity of BZ (omega) receptor ligands on defensive behaviors in mice: evaluation of the importance to intrinsic efficacy and receptor subtype selectivity. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1999;23:81–98. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo I, Bevilaqua LR, Rossato JI, Bonini JS, Da Silva WC, Medina JH, et al. The connection between the hippocampal and the striatal memory systems of the brain: a review of recent findings. Neurotox Res. 2006;10:113–121. doi: 10.1007/BF03033240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna JM, Kalant H, Chau A, Shah G. Rapid tolerance and crosstolerance to motor impairment effects of benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Skelton RW. Diazepam impairs acquisition but not performance in the Morris water maze. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;38:651–658. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Skelton RW. Tolerance develops to the spatial learning deficit produced by DZP in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;56:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramerstorfer J, Furtmüller R, Vogel E, Huck S, Sieghart W. The point mutation gamma 2F77I changes the potency and efficacy of benzodiazepine site ligands in different GABAA receptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;636:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Crestani F, Benke D, Brunig I, Benson JA, Fritschy JM, et al. Benzodiazepine actions mediated by specific gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor subtypes. Nature. 1999;401:796–800. doi: 10.1038/44579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Möhler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABAA receptor subtype functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savić MM, Milinković MM, Rallapalli S, Clayton T, Joksimović S, Van Linn M, et al. The differential role of alpha1- and alpha5-containing GABA(A) receptors in mediating diazepam effects on spontaneous locomotor activity and water-maze learning and memory in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:1179–1193. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savić MM, Majumder S, Huang S, Edwankar RV, Furtmüller R, Joksimović S, et al. Novel positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors: do subtle differences in activity at alpha1 plus alpha5 versus alpha2 plus alpha3 subunits account for dissimilarities in behavioral effects in rats? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Stevens P, Atack JR, Sohal B, Worboys P. Rodent pharmacokinetics and receptor occupancy of the GABAA receptor subtype selective benzodiazepine site ligand L-838417. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2005;26:13–20. doi: 10.1002/bdd.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. Structure, pharmacology, and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Adv Pharmacol. 2006;54:231–263. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(06)54010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G. Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:795–816. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Craig CK, French AM. Agonist and antagonist effects of benzodiazepines on motor performance: influence of intrinsic efficacy and task difficulty. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur C, Fresu L, Howell O, McKernan RM, Atack JR. Autoradiographic localization of a5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;822:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry AV., Jr . Spatial navigation (water maze) tasks. In: Buccafusco JJ, editor. Behavioral Methods in Neuroscience. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 153–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Rosenberg HC, Chiu TH. Rapid down-regulation of [3H]zolpidem binding to rat brain benzodiazepine receptors during flurazepam treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Majumder S, Clayton T, Petrou S, VanLinn ML, Namjoshi OA, et al. Design, synthesis, and subtype selectivity of 3,6-disubstituted β-carbolines at Bz/GABA(A)ergic receptors. SAR and studies directed toward agents for treatment of alcohol abuse. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:7548–7564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]