Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Artificial buffers such as HEPES are extensively used to control extracellular pH (pHe) to investigate the effect of H+ ions on GABAA receptor function.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

In neurones cultured from spinal cord dorsal horn (DH), dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and cerebellar granule cells (GC) of neonatal rats, we studied the effect of pHe on currents induced by GABAA receptor agonists, controlling pHe with HCO3- or different concentrations of HEPES.

KEY RESULTS

Changing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM at constant pHe strongly inhibited the currents induced by submaximal GABA applications, but not those induced by glycine or glutamate, on DH, DRG or GC neurones, increasing twofold the EC50 for GABA in DH neurones and GC. Submaximal GABAA receptor-mediated currents were also inhibited by piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane or imidazole. PIPES and HEPES, both piperazine derivatives, similarly inhibited GABAA receptors, whereas the other buffers had weaker effects and 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid had no effect. HEPES-induced inhibition of submaximal GABAA receptor-mediated currents was unaffected by diethylpyrocarbonate, a histidine-modifying reagent. HEPES-induced inhibition of GABAA receptors was independent of membrane potential, HCO3- and intracellular Cl- concentration and was not modified by flumazenil, which blocks the benzodiazepine binding site. However, it strongly depended on pHe.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Inhibition of GABAA receptors by HEPES depended on pHe, leading to an apparent H+-induced inhibition of DH GABAA receptors, unrelated to the pH sensitivity of these receptors in both low and physiological buffering conditions, suggesting that protonated HEPES caused this inhibition.

Keywords: GABAA receptors, piperazine, pH buffers, HEPES, bicarbonate, protons, hydrogen ions

Introduction

GABAA receptors are ligand-gated ions channels activated by GABA (receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2011). The conductance mediated by these receptors under physiological conditions is largely due to Cl- ions, but a significant component of GABAA receptor-mediated conductance involves HCO3- ions (Kaila and Voipio, 1987; Kaila et al., 1990; Voipio et al., 1991). The equilibrium of HCO3- with CO2 represents the main buffer system in the brain for hydrogen ions (H+). Like most neurotransmitter receptors, GABAA receptors can be modulated by extracellular protons (Traynelis, 1998), which might induce potentiation or inhibition of GABAA receptor function, or alternatively may not affect GABAA receptors. The effect of extracellular protons depends on the type of neurones considered (Robello et al., 1994; Krishek et al., 1996; Pasternack et al., 1996), the stage of neuronal development (Krishek and Smart, 2001), whether the receptors are activated by synaptically released or exogenously applied GABA (Mozrzymas et al., 2003), or whether GABA is applied at saturating or non-saturating concentrations (Pasternack et al., 1996; Huang and Dillon, 1999; Mozrzymas et al., 2003).

The differential sensitivity to extracellular pH (pHe) of native GABAA receptors displayed by distinct neuronal types and developmental stages has been ascribed to differences in the subunit composition of these receptors (Krishek et al., 1996; Huang and Dillon, 1999; Wilkins et al., 2002). A single histidine residue located at the external portal of the ion channel at position 267 of the β subunit (His267) has been identified as responsible for the H+-induced potentiation of α1βi receptor function, observed at both non-saturating and saturating GABA concentrations (Wilkins et al., 2002). The substitution of this histidine residue by an alanine removed the H+-induced potentiation of these receptors, uncovering an apparent H+-induced inhibition occurring only at non-saturating GABA concentrations (Wilkins et al., 2002).

Interestingly, activation of GABAA receptors, from slices of CNS tissue, by exogenous GABA agonists induces pHe shifts (Chen and Chesler, 1992; Kaila et al., 1992), and the permeability of GABAA receptors to HCO3- can induce an extracellular alkalinization occurring during normal GABAergic synaptic transmission (Kaila et al., 1992; 1993).

A widely used protocol to assess the role of endogenous pHe transients is to evaluate the consequences of preventing such pH transients by increasing the pHe buffering capacity with HEPES or related H+ buffering molecules, in order to ‘clamp’ pHe (DeVries, 2001; Palmer et al., 2003; Davenport et al., 2008; Dietrich and Morad, 2010), but very few authors have used physiological buffer to address this issue (Makani and Chesler, 2007).

In the present study, our objective was to examine whether (i) the currents induced by activation of native GABAA receptors from various regions of the nervous system in rats were modified by clamping pHe with artificial pH buffers; (ii) the effects of these artificial buffers were related to their buffering abilities or to a direct action on the GABAA receptors and (iii) the real/physiological pH sensitivity of GABAA receptors was altered by these artificial buffers. We used neurones of the dorsal horn (DH) of the spinal cord, as this structure is subject to activity-dependent pH transients (Sykova, 1998) as well as dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones and cerebellar granule cells (GCs).

Surprisingly, at commonly used concentrations (≤20 mM), HEPES, piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (TRIS) and imidazole strongly inhibited GABAA receptor-mediated currents induced by non-saturating concentrations of GABAA agonists. The inhibition induced by HEPES was specific for GABAA receptors and was independent of extracellularly located histidines, the benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors, membrane potential, intracellular Cl- concentration and HCO3- ions. However, the inhibition of GABAA receptors by HEPES depended on pHe, leading to an apparent H+-induced inhibition of GABAA receptors in DH neurones that did not correspond to the real/physiological pH sensitivity displayed by these receptors in physiological buffering conditions.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the rules of the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) and the French Department of Agriculture (License no. 67–337 to S. Hugel). The results of all studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (McGrath et al., 2010). We used Sprague Dawley rats born in the animal facility of our Institute.

Culture of DH neurones

The technique for preparing primary cultures of superficial laminae I–III neonatal DH neurones from 3- to 4-day-old rats has been described in detail elsewhere (Jo et al., 1998a, b; Hugel and Schlichter, 2000). Briefly, after decapitation, the dorsal third of the spinal cord was cut and digested enzymatically for 45 min with papain (20 IU·mL−1, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in oxygenated divalent cation-free Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The enzymic action was stopped by adding 3 mL of EBSS containing bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1 mg·mL−1, Sigma Aldrich), trypsin inhibitor (10 mg·mL−1, Sigma Aldrich) and DNase (0.01%), and a mechanical dissociation was performed with a 1 mL plastic pipette. The homogenate was carefully layered on top of 4 mL of a solution of composition similar to that described above, except that the concentration of BSA was increased to 10 mg·mL−1. After centrifugation (40× g for 5 min), the supernatant was replaced by culture medium, the composition of which was: minimum essential medium α (MEM-α), containing fetal calf serum (5% v/v), heat-inactivated horse serum (5% v/v), penicillin and streptomycin (50 IU·mL−1 each, all from Gibco), insulin (5 mg·mL−1), putrescine (100 nM), transferrin (10 mg·mL−1), and progesterone (20 nM, all from Sigma Aldrich). The neurones were plated in 35 mm plastic culture dishes (Corning Life Sciences, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) coated with collagen and maintained in a water-saturated atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C. Two days after seeding, cytosine arabinoside (10 µM, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the culture medium for 12 h to reduce glial proliferation.

Culture of DRG neurones

The culture procedure used was essentially the same as that previously described (Bowie et al., 1994; De Roo et al., 2003). Neonatal (3–5 days old) rats were decapitated and lumbar DRG were dissected and collected in PBS. After removal of the attached dorsal and ventral roots under a stereomicroscope, the ganglia were washed with divalent-free PBS and incubated with trypsin (0.5 g·L−1, Seromed, Vienna, Austria) for 25 min at 37°C. Enzymatic dissociation was terminated by removing the dissociation medium and adding an excess volume of culture medium (MEM-α containing heat-inactivated horse serum (10% v/v), and penicillin and streptomycin (50 IU·mL−1 each, all from Gibco). Mechanical dissociation of the DRGs into single cells was performed with a plastic pipette in culture medium by mild trituration. The dissociated primary sensory neurones were then plated in 35 mm plastic culture dishes (Corning) coated with poly-L-lysine (10 µg·mL−1, Sigma Aldrich) before seeding the neurones. Cultures were maintained in a water-saturated atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C for 1–48 h before use.

Culture of cerebellar GCs

Cerebellar cortices were dissected from 7-day-old rats, anaesthetised with ketamine (Imalgene; 50 mg mL-1, 0.15 ml i.p. injection). Neurones were dissociated mechanically with a 1 mL plastic pipette in GC culture medium, the composition of which was: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco), fetal calf serum (10%), and penicillin and streptomycin (50 IU·mL−1 for each); KCl concentration was adjusted to 25 mM. After centrifugation (40 g for 5 min), cells were resuspended in 3 mL of EBSS containing BSA (1 mg·mL−1; Sigma Aldrich), and the homogenate was deposited on the top of 4 mL of EBSS containing 10 mg·mL−1 of BSA. After centrifugation (40× g for 5 min), the supernatant was replaced by GC culture medium and the cells were plated on 35 mm plastic culture dishes (Corning) coated with poly-L-lysine at 10 µg·mL−1 (Sigma Aldrich). Cultures were maintained in a water-saturated atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C.

Culture of CHO cells expressing human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors

Human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor-expressing division-arrested CHO cells produced by ChanTest (Cleveland, OH, USA) were obtained from Cambridge Bioscience (Cambridge, UK). The cells were plated in 35 mm plastic culture dishes (Corning) coated with poly-L-lysine (10 µg·mL−1, Sigma Aldrich) before seeding the neurones. The culture medium was: Ham's F12 (Gibco), fetal calf serum (5% v/v, Gibco), and penicillin and streptomycin (50 iu·mL−1 each, Gibco). Cultures were maintained in a water-saturated atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C for 12 h and used within 3 days.

Drugs and application of substances

The following hydrogen ion buffers have been tested: HEPES, MOPS, imidazole, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) and PIPES (all from Sigma Aldrich), and TRIS (Research Organics, Cleveland, OH, USA). Diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the bath solution just before use. The following substances were prepared as 1000 times concentrated stock solutions in H2O: GABA, glutamate, glycine, isoguvacine and muscimol, or in EtOH: ethoxyzolamide and flumazenil (all from Sigma Aldrich). GABAA agonists, glutamate and glycine were applied locally, that is close to the recorded neurone, by means of U-tube (Krishtal and Pidoplichko, 1980) connected to a solenoid valve controlled by a pulse generator (Winston Electronics, St. Louis, MO, USA), which allowed rapid (<100 ms) solution exchange.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological experiments were performed at room temperature on neurones that had developed in culture for 1–3 days (DRG), 3–5 days (GCs) and 7–15 days (DH neurones). Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were made with a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA) and low resistance (3–4 MΩ) electrodes. All external solutions tested contained (in mM): NaCl 135, KCl 5, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, hydrogen ions buffer(s) and sucrose to adjust the osmolarity to ∼330 mOsm (see below).

For experiments with solutions containing artificial pH buffers only, the pH was directly adjusted at either 6.8, 7.3 or 7.8. In solutions containing bicarbonate as the only pH buffer (26 mM), the pH was set by the CO2/O2 ratio using gas mixing pumps (Wösthoff, Bochum, Germany) that mixed gas at fixed ratios depending on the gears selected: pH was set at 6.7 with 20% CO2, 7.3 with 5% CO2 and 7.7 with 2% CO2. The average pH values measured directly in the bath were 6.76 ± 0.01 with 20% CO2, 7.33 ± 0.01 with 5% CO2 and 7.74 ± 0.01 with 2% CO2. When artificial pH buffers were added to bicarbonate-buffered solutions, the pH was first set with CO2 equilibration, then the buffer was added and pH was titrated back to its previous value with NaOH. The pH was checked before and after all experiments.

Increasing HEPES concentration means increasing osmolarity. The iso-osmolarity of all solutions was checked and adjusted to ∼330 mOsm with sucrose. With a non-adjusted extracellular solution (osmolarity: ∼300 mOsm) in the bath, rapid application of extracellular solution adjusted to 330 mOsm with 30 mM of sucrose induced no significant current (current amplitude: 3.8 ± 1 pA, n= 7).

Depending on the type of experiment, we used different pipette solutions in order to set the Cl- equilibrium potential (ECl) at different values. ECl was set at −90 mV with a pipette containing (in mM): Cs2SO4 80, HEPES 10, MgCl2 2, MgATP 2, NaGTP 0.2 and pH 7.3. ECl was set at −60 mV with a pipette containing (in mM): Cs2SO4 75, HEPES 10, EGTA 10, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 5, MgATP 2, NaGTP 0.2 and pH 7.3. ECl was set at 0 mV with a pipette containing (in mM): CsCl 125, HEPES 10, EGTA 10, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 5, MgATP 2, NaGTP 0.2 and pH 7.3. For all solutions, the osmolarity was adjusted to 330 mOsm with sucrose.

Electrical stimulation

The stimulation procedure was identical to that described previously for the same culture preparation (Jo et al., 1998a, b; Hugel and Schlichter, 2000). Extracellular electrical stimulation of the cell body of the presynaptic neurone triggered the synaptic release of GABA, which produced a fast inhibitory postsynaptic current (eIPSC). Stimulation was either performed with isolated stimulus or with short pairs (interval 400 ms) of stimuli (0.1 ms in duration) delivered at 0.1 Hz and having amplitudes between −10 and −20 V.

Data acquisition and analysis

Voltage and current traces were stored digitally on a computer (10 kHz). Acquisition and analysis were performed with the pCLAMP software (versions 8.2 and 9.0, Molecular Devices).

Data analysis

Dose-response curves for GABA (Figure 4A and B) were described with a function involving a Hill coefficient, Imax/{1 + (EC50GABA/[GABA])n}, where EC50GABA, the concentration of GABA inducing half the maximum response Imax, was multiplied by a factor (1 +[HEPES]/KHEPES) to provide an apparent EC50 taking into account the inhibitory effect of HEPES. Because responses were normalized with respect to 30 µM GABA and 1 mM HEPES conditions, the following function was used for curve fitting:

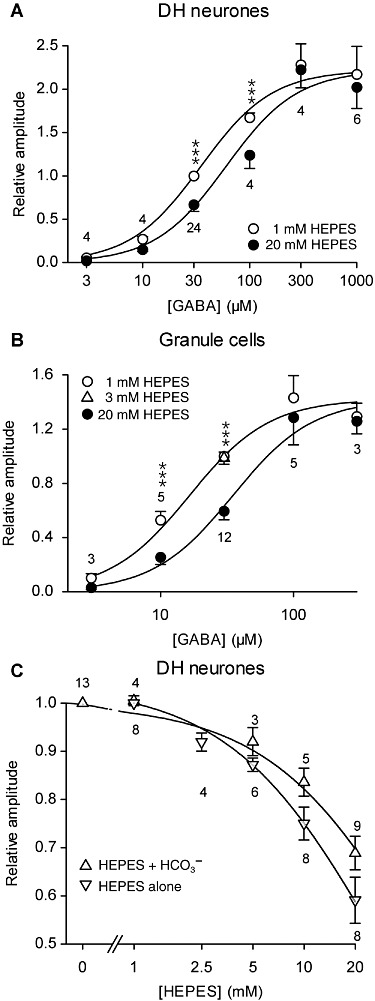

Figure 4.

In DH neurones and GCs, HEPES inhibited the currents induced by non-saturating GABA concentrations in a dose-dependent manner (constant pH 7.3). (A and B) Concentration-response curves of the maximal current amplitude induced by GABA in DH neurones (A) and GCs (B) in the presence of 1 mM or 20 mM HEPES (A) or 1mM, 3mM and 20mM HEPES (B). The maximal current was normalized to the current induced by 30 µM GABA in the presence of 1 mM HEPES. Solid lines correspond to a global curve fitting of the pooled data using equation (1). Parameter values were KGABA= 33.6 µM, KHEPES= 25.5 mM, Hill number n= 1.31 for DH neurones (A), and KGABA= 15.5 µM, KHEPES= 15.9 mM, n= 1.45 for GC neurones (B). ***P < 0.001, significantly different from values with 20 mM HEPES; Tukey test following repeated measures anova. (C) Concentration-response curves of the current amplitude induced by 30 µM GABA in DH neurones in the presence of various concentrations of HEPES, with and without HCO3-/CO2-buffering. Values with HCO3-/CO2-buffering are normalized to the amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA in the absence of extracellular HEPES and values with HEPES as the only pHe buffer are normalized to the amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA in the presence of 1 mM HEPES. Solid lines correspond to curve fitting with equation (2). Numbers on the graph correspond to the number of neurones recorded. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. All experiments were performed at the same pHe 7.3.

|

(1) |

Parameters EC50GABA, KHEPES and n were determined by non-linear curve fitting using KyPlot 2.15 (KyensLab, Tokyo, Japan).

Similarly, the dose-response curves with respect to HEPES concentration (Figure 4C) were modelled using the function Amax/(1 +[HEPES]/KHEPES). Normalized responses were actually fitted with the following function:

| (2) |

with B= 0 for data obtained with bicarbonate [normalized with respect to (HEPES) = 0] and B= 1 for data with HEPES alone [normalized with respect to (HEPES) = 1].

Dose-response curves in CHO cells (Figure 5A) were also described with a function involving a Hill coefficient, Imax/{1 + (EC50GABA/[GABA])n}, where EC50GABA is the apparent EC50 for GABA for a given concentration of HEPES. In that case, responses were normalized with respect to 300 µM GABA, so that the following function was used for curve fitting:

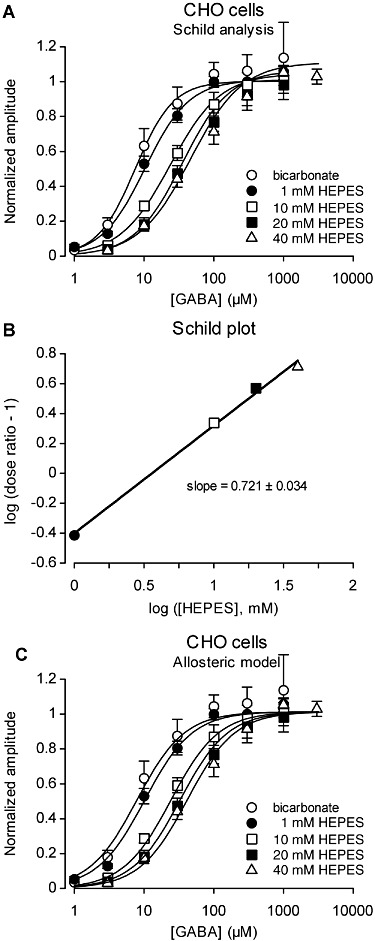

Figure 5.

In CHO cells expressing the human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, HEPES inhibited the currents induced by non-saturating GABA concentrations in a dose-dependent manner (constant pH 7.3). (A) Concentration-response curves of the maximal current amplitude induced by GABA in CHO cells in the presence of HCO3- only (no HEPES) or 1, 10, 20 and 40 mM HEPES only (no HCO3-). Data for each HEPES concentration were fitted with equation (3) (solid lines). Apparent EC50 values were 7.5, 10.4, 23.8, 35.4 and 46.2. The mean Hill number was 1.33 ± 0.08 (n= 5). Data shown are the means of normalized values ± SEM, recorded from 6 cells with, and 12 cells without, bicarbonate. All experiments were performed at the same pHe 7.3. (B) Corresponding Schild plot established with apparent EC50 values obtained from (A). (C) Experimental data were well fitted (correlation coefficient = 0.9061, n= 227) by an allosteric model (equation 4) introducing a cooperativity factor to explain the inhibitory effect of HEPES. Data points are the same as in (A).

| (3) |

The EC50 values at 1, 10, 20 and 40 mM HEPES were divided by the EC50 measured in the absence of HEPES (HCO3-/CO2 buffer) to obtain the dose ratio and derive the corresponding Schild plot (Figure 5B).

A global fit on the same data was also performed using an allosteric model to describe the negative modulator effect of HEPES (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002). A cooperativity factor α was introduced in the apparent EC50 for GABA that was now defined as:

leading to the following function for curve fitting of normalized amplitudes:

|

(4) |

Individual data were always used for curve fitting and average values for illustration.

Results are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using KyPlot 2.15 (KyensLab) or Statistica 5.1 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Group means were compared with Student's t-test, one-way anova or repeated-measures two-way anova, followed by Tukey's post hoc multiple comparison test. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

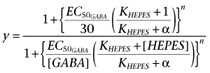

High concentrations of HEPES inhibit GABAA agonist-induced currents on DH, DRG and GC neurones

To probe the consequences of strong pH buffering on GABA receptor function, we used cultured DH neurones, sensory neurones of the DRG and cerebellar GCs. We compared the effects of local and rapid GABA applications under strong pH buffering conditions with 20 mM HEPES, and weaker pH buffering conditions with 1 mM HEPES, all at constant pHe of 7.3. For these experiments, the bath solution contained 10 mM HEPES and GABAA receptor agonists were applied every 2 min for 750 ms, in solutions containing either 1 mM or 20 mM HEPES. In all neurones, the reproducibility and the reversibility of the responses were tested (Figure 1A). The currents induced by GABA at a non-saturating concentration (30 µM) were recorded at a holding potential of 0 mV with ECl=−90 mV. These currents were always strongly and reversibly reduced in the presence of 20 mM HEPES as compared with 1 mM HEPES, in all neurones of all the three preparations tested (Figure 1B). The current induced by 30 µM GABA was significantly reduced in 20 mM HEPES (vs. 1 mM) by 32 ± 2% in DH neurones, by 55 ± 13% in DRG neurones and by 40 ± 4% in GCs. In the same conditions (20 mM HEPES vs. 1 mM HEPES, constant pH 7.3, 750 ms of drug application every 2 min), a significant reduction of current amplitude was also observed with 30 µM isoguvacine and with 1 µM muscimol, two selective GABAA receptor agonists, indicating that 20 mM HEPES had an inhibitory effect on GABAA receptor function (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

HEPES inhibited the currents induced by rapid applications of GABAA receptor agonists in spinal cord DH neurones, DRG neurones and cerebellar GCs. (A) Changing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM reduced the maximal amplitude of the currents induced by 30 µM GABA in cultured DH neurones. Holding potential: 0 mV; duration of GABA application: 750 ms. (B) Average maximal amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA in presence of 20 mM HEPES normalized to the current recorded in presence of 1 mM HEPES. In DH and DRG neurones and GCs, increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM significantly reduced the peak currents induced by 30 µM GABA. (C) Average maximal amplitude of the current induced in DH neurones by GABAA receptor agonists, glycine and glutamate in presence of 20 mM HEPES, normalized to the current recorded in presence of 1 mM HEPES. Only the currents induced by GABAAR agonists applied at non-saturating concentrations were inhibited when HEPES concentration was increased. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. The values within the histogram bars correspond to the number of neurones recorded. All experiments were performed at pHe 7.3. Symbols show ratio values significantly different from 1: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

The currents induced by rapid and local applications of glycine (30 µM, recorded in the same conditions as for GABA applications) and glutamate (30 µM, recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV) remained unchanged in 20 mM versus 1 mM HEPES, indicating a specific action of HEPES on GABAA receptors but neither on glycine nor on glutamate receptors (Figure 1C).

Characteristics of GABAA receptor inhibition by high concentrations of HEPES

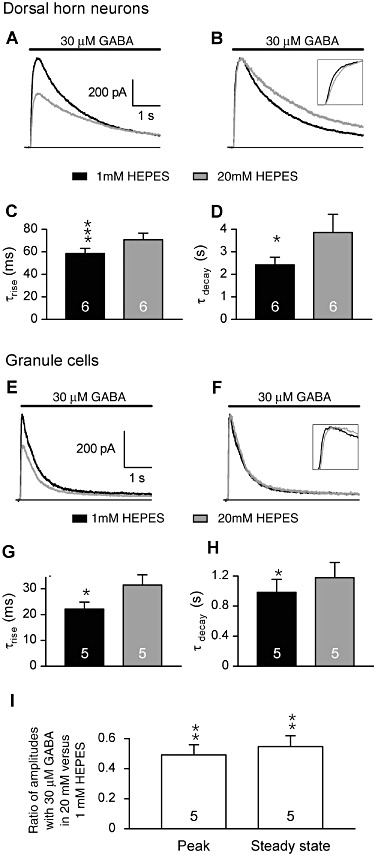

We determined the effect of increasing HEPES concentrations on the rising and decaying phases of the currents induced by applications of GABA (Figure 2). We detached patched neurones from the dish by lifting the patch pipette and maintained them close (∼100 µm) to the perfusion system, allowing to exchange the solution with a time constant <20 ms and to examine the effect on the current rising phase. We applied 30 µM GABA for 5 s, in order to examine the effect on the decaying phases of the currents. In both DH neurones and GCs, increasing the HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM significantly increased the time constant (τrise) of the mono-exponential function fitting the rising phase in DH neurones (Figure 2A–C) and in GCs (Figure 2E–G). The time constant of the mono-exponential function fitting the decaying phase of the GABA-induced current (τdecay) was also increased by changing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM, in DH neurones (Figure 2B and D) and in GCs (Figure 2F and H)]. With these long applications of GABA (5 s), a steady state plateau current following the peak current was observed in GCs (Krishek and Smart, 2001). Its amplitude was determined as the value of the constant added to the mono-exponential function fitting decaying phase of the GABA-induced current. Both peak and steady state currents induced by 30 µM GABA in GCs were significantly reduced in 20 mM HEPES, compared with values in 1 mM HEPES (Figure 2E, F and I). The effect of HEPES was not different on the peak and on the steady state current (paired Student's t-test, t4= 0.501, P= 0.642, n= 5; Figure 2I). In both DH neurones and GCs, the increase of HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM had no significant effect on the currents induced by saturating concentrations of GABA (1 mM): the amplitude remained similar (decrease of 6 ± 2%, paired Student's t-test, P= 0.08, n= 3 in DH neurones; change of 0 ± 3%, P= 0.87, n= 3 in GC); the τrise remained similar (30.7 ± 0.8 ms vs. 28.6 ± 0.6 ms in 1 mM and 20 mM HEPES, respectively, P= 0.66, n= 3 in DH neurones; 17.3 ± 3.1 ms vs. 18 ± 3.4 ms in 1 mM and 20 mM HEPES, respectively, P= 0.86, n= 3 in GC); the τdecay remained similar (τdecay increase of 12 ± 14%, P= 0.47, n= 3 in DH neurones; τdecay change of 0 ± 2%, P= 0.98, n= 3 in GC).

Figure 2.

HEPES slowed the kinetics of the currents induced by rapid applications of 30 µM GABA on spinal cord DH neurones and GCs. Patched neurones were detached from the dish and maintained close (∼100 µm) to the perfusion system. (A and B) The currents induced by 5 s applications of GABA (30 µM) in a DH neurone displayed slower rise and decay kinetics. Traces in A are normalized in B to compare kinetics. (E–F) The currents induced by 5 s applications of GABA (30 µM) in a GC displayed slower rise and decay kinetics. Traces in E are normalized in F to compare kinetics. (C and G) The average time constant values of the exponential functions fitting the current rise in DH (C) and GC (G) neurones significantly increased in 1 and 20 mM HEPES. (D and H) The average time constants of the exponential functions fitting the current decay in DH (D) and GC (H) neurones were significantly increased in 20 mM HEPES as compared with 1 mM HEPES. (I) Increasing HEPES from 1 to 20 mM similarly reduced the amplitude of the peak and of the steady state currents induced by 30 µM GABA in GC. All experiments were performed at pHe 7.3. Data in bar graphs are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

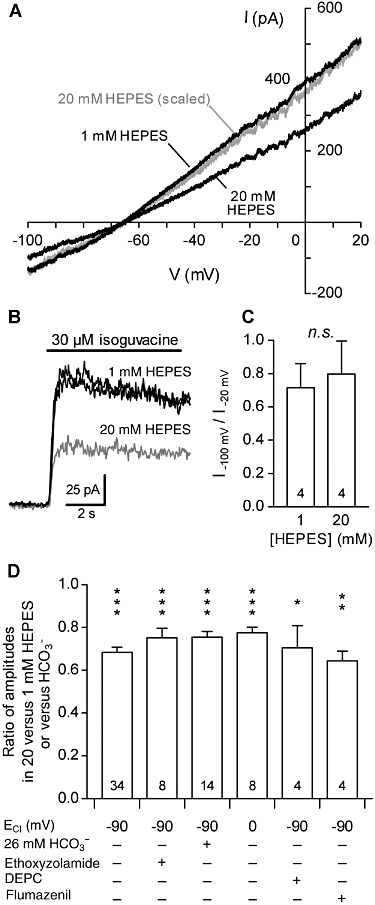

To assess a possible action of HEPES as a channel blocker on the pore of GABAA receptors, we determined whether its effect depended on the direction of the current flow. The current–voltage relationship (I–V) of GABAA receptor-mediated conductance was determined by applying 3 s monotonic voltage ramps from −100 to +20 mV before and during the activation of GABAA receptors in DH neurons, in the presence of 20 mM or 1 mM HEPES (Figure 3A). To display a reliable I–V relationship, the activated conductance should remain constant during the application of the voltage ramps. In these experiments, ECl was set at −60 mV, and we used isoguvacine (30 µM, >4 s applications) as the GABAA receptor agonist. At this concentration, isoguvacine induced a GABAA receptor-mediated current of relatively constant amplitude, indicative of a weak and slow desensitization of the GABAA receptors (Figure 3B). We compared the effect of increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM on isoguvacine-induced currents by measuring a rectification index, calculated as the ratio of the absolute values of the current amplitudes measured at −100 and −20 mV. Although increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM reduced the 30 µM isoguvacine-induced conductance, the rectification index remained unchanged (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of inhibition of GABAA receptors mediated by HEPES in DH neurones. (A) Effect of increasing extracellular HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM on the current–voltage (I–V) relationship of the conductance induced by 30 µM isoguvacine. Membrane currents triggered by 3 s monotonic voltage ramps from −100 to +20 mV were measured before and during the application of isoguvacine. The black traces correspond to the difference of the currents recorded during and before the application of isoguvacine at the two tested concentrations of HEPES. The grey trace corresponds to the isoguvacine-induced current recorded with 20 mM HEPES scaled to the isoguvacine-induced current recorded with 1 mM HEPES. Note the similar current rectification. ECl was fixed at −60 mV. (B) Superimposed traces of 30 µM isoguvacine-induced currents. The grey trace corresponds to currents recorded with 20 mM HEPES; the black traces correspond to currents recorded with 1 mM HEPES before and after testing the effect of GABA in the presence of 20 mM HEPES. Isoguvacine (30 µM) was used as the GABAA agonist for voltage ramp experiments because it induced only a weak and slow desensitization of the GABAARs. (C) Index of rectification of the current induced by 30 µM isoguvacine, calculated as the ratio of current amplitude absolute values measured at −100 and −20 mV. (D) Relative amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA in presence of 20 mM HEPES under various conditions. The current amplitude was normalized to the amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA in presence of 1 mM HEPES (experiments without HCO3-) or without HEPES (experiments under HCO3-/CO2-buffering conditions). The inhibition induced by 20 mM HEPES remained similar and significant under all the conditions tested: when ECl was fixed at 0 mV or −90 mV; under HCO3-/CO2-buffering conditions (HCO3-); under HCO3--free conditions obtained by saturating all solutions with O2 in the presence of ethoxyzolamide (10 µM), a membrane-permeable carbonic anhydrase inhibitor; or when extracellularly-accessible histidines were modified by DEPC (1 mM) pre-treatment. Numbers in the bars correspond to the number of recorded neurones. All experiments were performed at pH 7.3. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

As GABAA receptors are also permeable to HCO3- ions (Kaila et al., 1993), high HEPES buffering might contribute to limit local pH changes mediated by these ions in the close vicinity of GABAA receptors. Even with the HEPES-based, HCO3--free bath solutions we used, a significant amount of HCO3- might be produced within cells by carbonic anhydrase-catalysed conversion of atmospheric/metabolic CO2 (Boussouf et al., 1997). We therefore tested whether the inhibition of GABA-induced currents by 20 mM of HEPES was different in HCO3--free conditions and physiological HCO3- conditions (i.e. 26 mM HCO3-) on DH neurones. The HCO3--free conditions were obtained by saturating all the solutions with O2 in the presence of ethoxyzolamide (10 µM), a membrane-permeable carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. In these conditions, increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM still significantly inhibited currents induced by 30 µM GABA (Figure 3D). Similarly, the current induced by GABA (30 µM) in a HCO3-/CO2-buffered solution (i.e. physiological buffering conditions) was significantly inhibited by adding 20 mM HEPES at constant pH (Figure 3D). Moreover, the inhibition induced by 20 mM HEPES was similar to that induced by 1 mM HEPES or HCO3-/CO2-buffered solution (unpaired Student's t-test, P= 0.9).

In previous experiments, ECl was set at −90 mV (and the neurones recorded at a holding potential of 0 mV). We next tested whether the HEPES-mediated inhibition of the currents induced by GABA persisted when the intracellular chloride concentration was increased. We therefore adjusted ECl to 0 mV and measured GABAA receptors -mediated currents at a holding potential of −60 mV. In these conditions, increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM still significantly reduced the amplitude of the GABA-induced current by 33 ± 3% (Figure 3D).

A histidine residue (His267), critical for the modulation of α1βi GABAA receptors by protons, has been identified on β subunits (Wilkins et al., 2002). We therefore tested if such an extracelllularly accessible histidine was responsible for the inhibition of GABAA-mediated currents by 20 mM HEPES, using DEPC (1 mM), a histidine-modifying reagent. The inhibition of 30 µM GABA-induced current, caused by increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM, remained similar after DEPC treatment of DH neurones (Figure 3D).

To define whether the inhibition mediated by HEPES involved an action at the benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors, we blocked this site using flumazenil (2 µM). The inhibition of the 30 µM GABA-induced current, caused by increasing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM, was unchanged in presence of flumazenil (Figure 3D).

To characterize the effect of 20 mM versus 1 mM HEPES on native GABAA receptors at constant pH (7.3), we constructed dose-response curves measuring GABA-induced currents in these two HEPES concentrations (Figure 4). In both GCs and DH neurones, 20 mM HEPES inhibited non-saturating GABA-induced currents compared with the currents in 1 mM HEPES. In DH neurones (Figure 4A), repeated measures anova (RM-anova) showed significant effects of GABA (F5,40= 68.6, P < 0.0001) and HEPES (F1,40= 41.8, P < 0.0001) as well as of the interaction of the two factors (F5,40= 6.2, P= 0.00024). A global fit on pooled data, using equation (1) with [HEPES] equal to either 1 or 20 mM, lead to a value of 33.6 µM for KGABA and to an inhibition constant KHEPES of 25.2 mM for HEPES, which means that the apparent GABA EC50 was shifted from 34.9 to 60.0 µM by increasing HEPES from 1 to 20 mM at constant pH (7.3). Similarly, in GCs (Figure 4B), KGABA was equal to 15.5 µM and KHEPES to 15.9 mM, so that the GABA EC50 was shifted from 16.5 to 35.0 µM. RM-anova also showed a highly significant effect of GABA, HEPES and their interaction term (F4,34= 78.5, P < 0.0001; F1,34= 58.5, P < 0.0001; F4,34= 68.6, P < 0.0001 respectively). Interestingly, 20 mM HEPES had no effect at saturating GABA concentrations in both GCs and DH neurones (Figures 1C and 4A and B).

In DH neurones, HEPES was tested at various concentrations either alone or combined with the physiological buffer bicarbonate (26 mM, at a constant pH of 7.3). The amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA was normalized with respect to the current recorded in 1 mM HEPES or bicarbonate alone. The effect of HEPES was clearly dose dependent and was not saturated at concentrations lower than 20 mM of HEPES (Figure 4C). Fitting data with equation (2), values of KHEPES of 26.1 mM and 46.1 mM were found for data obtained with bicarbonate and with HEPES alone respectively.

Altogether, these data indicate that, at commonly used concentrations (5–20 mM), HEPES strongly reduced the submaximal GABAA-mediated currents in a concentration-dependent manner compared with physiological and/or low buffering conditions. This inhibition did not involve a channel-blocking action of HEPES, did not depend on HCO3- or intracellular Cl- concentrations and did not involve the benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors. Importantly, unlike the potentiation of α1βi GABAA receptors by protons (Wilkins et al., 2002), this HEPES-mediated inhibition did not involve a histidine residue.

Effect of HEPES on human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors expressed in CHO cells

Our data revealed a rightward shift in the GABA concentration–response curve (Figure 5A), and surmountability of HEPES antagonism with increasing GABA concentration that are suggestive of a competitive inhibition of GABAA receptors by HEPES. The Schild plot (Figure 5B) was well fitted by a linear regression (R= 0.9978). However, the Schild regression analysis did not support a simple competitive behaviour of HEPES, because the slope of that linear regression (0.721 ± 0.034) was significantly less than unity (extra sum-of-squares F test, F3,2= 67.3, P < 0.0001, when comparing with a model with slope fixed at 1). We therefore tested the possibility that GABA-induced currents are inhibited by HEPES through a non-competitive allosteric mechanism, also resulting in an increase of the apparent EC50 for GABA (Figure 5C). The model used (equation 4) was derived from equation 6 in Christopoulos and Kenakin (2002). A global fit on data points from all [GABA] × [HEPES] combinations provided the following values for the parameters (±asymptotic standard error estimated by the non-linear regression procedure): EC50GABA= 7.9 ± 0.8 µM, KHEPES= 2.8 ± 1.2 mM, nHill= 1.27 ± 0.07, cooperativity factor α= 0.13 ± 0.03. Note that the Hill number is close to that observed in Figure 5A for DRG neurons or cerebellar GCs (Figure 4).

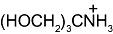

Effect of HEPES and other artificial buffers on GABAA receptors

We next examined whether other artificial buffers displayed similar effects on the amplitude of GABAA-mediated currents. We compared the amplitudes of the currents induced by rapid/local GABA (30 µM) applications on DH neurones under pH buffering conditions with 1 mM HEPES alone or with addition of 20 mM of another artificial buffer, all at constant pH (7.3) and osmolarity. We tested the following molecules, all currently used to buffer hydrogen ions in physiological pH range (6.5 < pKa < 8.1 at 20°C, Table 1): PIPES, imidazole, MOPS and TRIS. PIPES belongs, as HEPES, to the buffers selected by Good et al. (1966). We also tested the effect of MES, used in a pH range below 7.3 (i.e. MES pKa= 6.1).

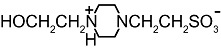

Table 1.

Structure and pKa of tested buffers

| Buffer | Structure | pKa at 25°C |

|---|---|---|

| MOPS |  |

7.2 |

| C7H15NO4S | ||

| MES |  |

6.1 |

| C6H13NO4S | ||

| HEPES |  |

7.5 |

| C8H18N2O4S | ||

| PIPES |  |

6.8 |

| C8H18N2O6S2 | ||

| TRIS |  |

8.1 |

| C4H12NO3 | ||

| Imidazole |  |

7.0 |

| C3H4N2 |

Modified and supplemented after Good et al. (1966).

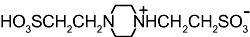

All these buffers, except MES, significantly and reversibly reduced the amplitude of currents induced by 30 µM GABA (Figure 6A). Interestingly, MES had no significant effect on the GABA-induced current (Figure 6A), leaving the possibility that the buffering abilities of the pH buffers might be the origin of their effect on GABAA receptors. However, the inhibition induced by the tested buffers was not stronger for buffers having pKa values closer to the pH of our experiments (7.3), as it would be expected if the buffering capacity was involved in this inhibition (Davenport et al., 2008). Indeed, the effect of 20 mM of HEPES and PIPES, two piperazineethanesulfonic acids, were similar, whereas the effects of HEPES were significantly different from those of imidazole and MOPS, although the pKa of these two buffers was closer to 7.3 (Figure 6B). TRIS (20 mM), displaying the highest pKa among the tested buffers, also had weaker effects than 20 mM HEPES. The effect of PIPES was significantly stronger than that of imidazole, MOPS or TRIS, which did not differ one from the other (one-way anova, F3, 23= 8.41, P= 0.0006).

Figure 6.

Effect of various pH buffers on the currents induced by 30 µM GABA in DH neurones. (A) Average amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM of GABA in presence of 20 mM of the tested buffer plus 1 mM HEPES, normalized to the current recorded in presence of 1 mM HEPES alone. PIPES, HEPES, TRIS, MOPS and imidazole (Imidaz) significantly inhibited the currents induced by 30 µM GABA. MES had no significant effect. (B) Extent of the inhibition mediated by the buffers tested related to the inhibition caused by 20 mM HEPES. The inhibition mediated by PIPES was similar to that mediated by HEPES. Imidazole-, MOPS- and TRIS-mediated inhibitions were significantly weaker than HEPES-mediated inhibition. Only MES, HEPES and PIPES correspond to buffers selected by Good et al. (1966). All experiments were performed at pH 7.3. Numbers within the histogram bars represent the number of neurones recorded. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

These data indicate that 20 mM HEPES, PIPES, imidazole, MOPS and TRIS significantly and reversibly reduced submaximal GABAARs-mediated currents, compared with buffering conditions similar to the physiological buffering conditions. Interestingly, MES, a buffer displaying a buffering range below the tested pH, had no effect. Importantly, HEPES and PIPES, two closely related piperazineethanesulfonic acids, had similar effects, which were significantly larger than those of TRIS, imidazole and MOPS, suggesting that inhibition of GABAA receptors by these distinct classes of pH buffering molecules might involve at least in part distinct mechanisms of action.

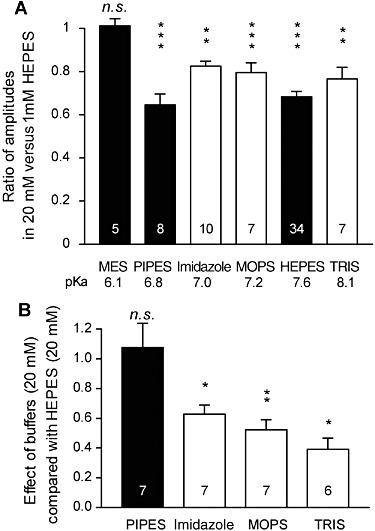

GABAA receptor inhibition mediated by HEPES is pH dependent

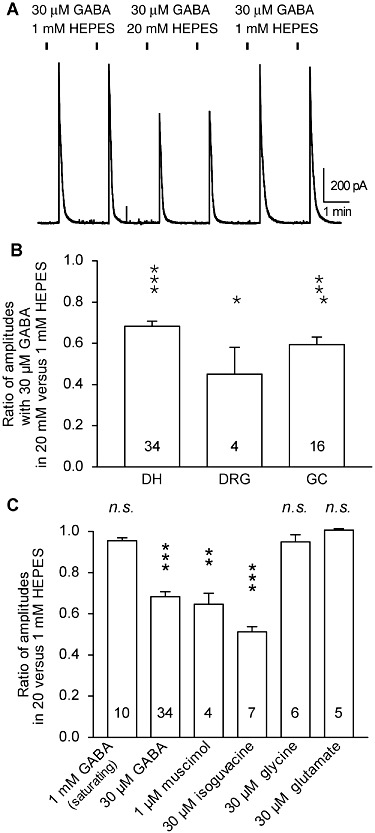

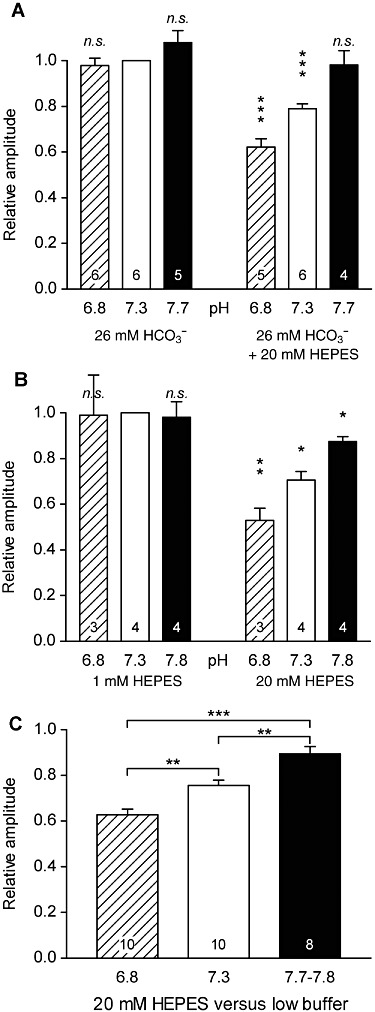

HEPES is a zwitterionic pH buffer: at its pKa value (7.6), near physiological pH (7.3), about half of the HEPES molecules are protonated and half are not protonated. In order to test the possibility that one of these two forms of HEPES is involved in the inhibition of GABAA receptors, we examined the amplitude of the 30 µM GABA-induced currents in presence of 20 mM HEPES, under HCO3-/CO2 buffering at three different pH values: 6.8, 7.3 and 7.7. These amplitudes were compared with that obtained on the same DH neurones in physiological buffer conditions at pH 7.3 (HCO3-/CO2-buffered solution; Figure 7A). pHe was changed by saturating the solutions with different CO2/O2 mixtures prepared with Wösthoff pumps (see Methods). At pH 7.7, 20 mM HEPES had no significant effect on 30 µM GABA-induced currents, compared with pH 7.3 in HCO3-/CO2-buffered solution; Figure 7Aright). At pH 7.3, 20 mM HEPES significantly reduced the 30 µM GABA-induced currents by 20 ± 3% and at pH 6.8, by 37 ± 3% (Figure 7Aleft).

Figure 7.

HEPES-mediated inhibition of GABAA receptors depends on pH, leading to an apparent inhibition by protons that did not correspond to the real/physiological pH sensitivity of these receptors in DH neurones. (A) Average maximal amplitude of the current induced by 30 µM GABA at low (6.8), physiological (7.3) and high (7.7) values of pH recorded under HCO3-/CO2-buffered conditions (physiological buffering conditions, left) and with addition of 20 mM HEPES (right). The amplitudes were normalized to the current recorded in HCO3-/CO2-buffered conditions at physiological pH (7.3). The pH value was set by the CO2/O2 ratio of the gas mixture used to saturate the solution. (B) Same as (A) but with 1 mM HEPES (left) or 20 mM HEPES (right) as the only buffer. At both physiological and low buffering conditions, the currents induced by 30 µM GABA remained similar, whereas they appeared as inhibited at low pH values when recorded with 20 mM HEPES. (C) Same data as in (A) and (B) except that responses were pooled and normalized to the value recorded at the same pH but in low/physiological buffering conditions. The inhibition by HEPES of 30 µM GABA-induced currents was significantly stronger at low pH than at high pH. Numbers within the histogram bars represent the number of neurones recorded. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

These data indicate an apparent pH sensitivity displayed by GABAA receptors in DH neurones recorded with 20 mM HEPES. In such conditions, these receptors are inhibited at pH 6.8, as compared with pH 7.3.

In order to test if this apparent pH sensitivity was caused by real pH sensitivity of GABAA receptors or by a pH-sensitive blocking effect of HEPES on GABAA receptors, we looked for the pH sensitivity of GABAA receptors in DH neurones using the physiological HCO3-/CO2 buffer (i.e. without any artificial buffer). pHe was changed by saturating the solutions with different CO2/O2 mixtures prepared with Wösthoff pumps. Remarkably, changing pH from 7.3 to 7.7 or 6.8 under these physiological conditions had no significant effect on membrane currents induced by 30 µM GABA. With respect to its value at pH 7.3 in HCO3-/CO2-buffered solution (Figure 7Aleft), the amplitude was not significantly changed at pH 6.8 or at pH 7.7.

Thus, under physiological pH buffering, submaximally activated GABAA receptors in DH neurones were not significantly modulated by protons at pH values between 6.8 and 7.8, whereas an apparent proton-mediated inhibition appeared in presence of 20 mM HEPES.

Similar data were obtained in conditions where HEPES was used as the only buffer (at 20 mM vs. 1 mM; Figure 7B). At pH 7.8, 20 mM HEPES reduced 30 µM GABA-induced currents by 13 ± 2%, compared with pH 7.3 in 1 mM HEPES (Figure 7Bright). At pH 7.3, 20 mM HEPES reduced 30 µM GABA-induced currents by 29 ± 4% and at pH 6.8, by 41 ± 9%. As in HCO3-/CO2-buffered conditions, 30 µM GABA-induced currents in 1 mM HEPES were not modified at pH 6.8 and 7.8, compared with values at pH 7.3 (Figure 7Bleft).

No significant difference was found between responses obtained with 26 mM HCO3- (Figure 7A) or with 1 mM HEPES (Figure 7B). We therefore pooled the data obtained under these two conditions in order to characterize the pH dependence of 20 mM HEPES-mediated inhibition of GABAA receptors in DH neurones. We compared in the same cells the amplitudes of the GABAA-mediated currents in 20 mM HEPES versus low/physiologically buffered solutions (1 mM HEPES or 26 mM HCO3-/CO2) at the same pH (Figure 7C). At pH 7.7–7.8, the current induced by 30 µM GABA in the presence of 20 mM HEPES represented 89 ± 3% of the current induced at the same pH by the same concentration of GABA under low/physiologically buffered conditions (n= 8). At pH 6.8, the relative amplitude was 62 ± 2% (n= 10). These values were significantly different from each other (one-way anova, F2,25= 17.67, P < 0.0001, followed by Tukey–Kramer test).

These data clearly indicate that GABAA receptors are inhibited by HEPES in a pH-dependent manner, suggesting that the protonated form of HEPES is responsible for this inhibition.

At saturating GABA concentration (1 mM) and in HCO3-/CO2-buffering conditions, these receptors are weakly potentiated by protons (average increase of 11 ± 3% at pH 6.8 vs. 7.3, paired Student's t-test, P= 0.048, n= 3; average decrease of 2 ± 0% at pH 7.7 vs. 7.3, paired Student's t-test, P= 0.044, n= 3).

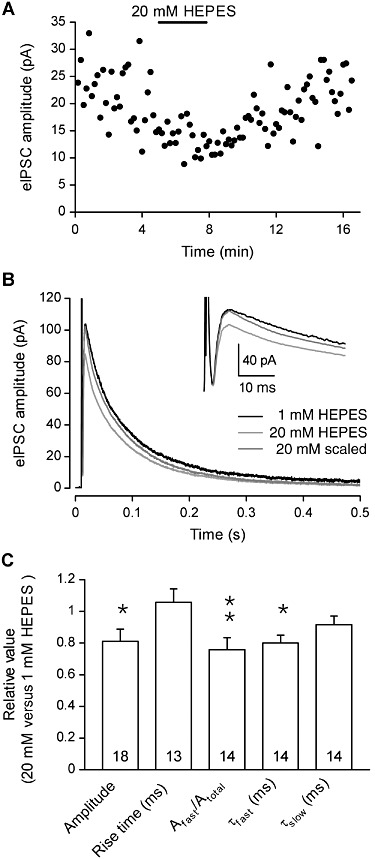

Effect of HEPES on GABAergic synaptic transmission

On cultured GCs, HEPES (24 mM) and PIPES (24 mM) significantly and reversibly reduced the amplitude of GABAergic miniature post-synaptic currents and modified their kinetics (Dietrich and Morad, 2010).

To assess the effects of HEPES on the GABAergic synaptic transmission between DH neurones, we recorded electrically evoked GABAergic inhibitory post-synaptic currents (eIPSCs) and tested the effects of increasing the concentration of HEPES. When the data of all the recorded neurones were pooled, changing HEPES concentration from 1 to 20 mM significantly reduced the GABAergic eIPSCs amplitudes by 19 ± 8% (Figure 8). The 10–90% rise time remained unchanged in 20 mM HEPES versus 1 mM HEPES (Figure 8). The decay time could be fitted with a biexponential function. The time constant of the fast component (τfast) was significantly decreased in 20 mM HEPES, compared with that in 1 mM HEPES (Figure 8C), whereas the time constant of the slow component (τslow) was not significantly modified in 1 mM HEPES, relative to that in 20 mM HEPES (Figure 8C). The relative contribution of the fast exponential in the synaptic current amplitude was significantly decreased (Figure 8C). The increase in HEPES concentration induced no changes in the paired-pulse ratio in most of the neurones tested (6/8), thereby indicating a post-synaptic mechanism of action. In the remaining 2/8 neurones, the paired-pulse ratio was modified, suggesting at least a pre-synaptic action of HEPES in a subset of GABAergic synapses. Moreover, the effect of 20 mM versus 1 mM HEPES on the amplitudes of GABAergic eIPSC was very variable across the recorded neurones population (ranging from an increase of 21% to a decrease of 71%). These results suggested that increasing HEPES concentration had complex pre- and/or post-synaptic effects on DH neurones, depending on the synapse involved.

Figure 8.

The amplitude of electrically evoked GABAergic IPSCs (eIPSCs) is reduced by HEPES in DH neurones. (A) In a neurone recorded with 1 mM HEPES, the superfusion with an extracellular solution containing 20 mM HEPES induced a reversible decrease in the amplitude of GABAergic eIPSCs. (B) Superimposed eIPSCs recorded in 1 mM and 20 mM HEPES. The dark grey trace corresponds to the currents recorded in 20 mM HEPES that was normalized to the peak of the currents recorded in 1 mM HEPES. The inset shows details of the initial part of the traces. The stimulus artefact was blanked for 20 mM HEPES traces. (C) Average values of GABAergic eIPSC amplitude and kinetic properties recorded with 20 mM HEPES, normalized to the values recorded in presence of 1 mM HEPES. All experiments were performed at constant pHe 7.3. Data represent the mean of normalized values ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ratio values significantly different from unity; n.s., not significant; paired Student's t-test.

Discussion and conclusions

HEPES and other artificial pH buffers are extensively used in cellular neuroscience in order to control pHe values. Setting pHe at different values with such artificial buffers is commonly used to assess the pH sensitivity of neurotransmitter receptors such as GABAA receptors. More recently, these buffers have been employed to reveal the effects of endogenous pHe changes by evaluating the consequences of using a high concentration of artificial buffers compared with low and/or physiological buffering conditions (DeVries, 2001; Palmer et al., 2003; Davenport et al., 2008; Dietrich and Morad, 2010).

In the present article, we demonstrate that HEPES inhibited GABAA receptor-mediated submaximal, but not saturating, responses in a dose-dependent manner. Currents induced by GABAA receptor agonists, but not glycine- and glutamate-induced currents, were modulated by HEPES, indicating a specific action of HEPES on GABAA receptors. We observed this inhibition for native GABAA receptors from various regions of the nervous system, including the periphery (DRG neurones), the spinal cord (DH neurones) and the brain (cerebellar GC), suggesting the wide occurrence of HEPES-sensitive GABAA receptors in the nervous system. Moreover, in GCs, both peak and steady state currents were similarly significantly inhibited suggesting that both rapidly and slowly desensitizing GABAA receptors of these neurones were sensitive to HEPES. Similarly, the amplitudes of GABAergic eIPSCs recorded in DH neurones were significantly reduced by increasing HEPES concentration.

This non-buffer-related inhibitory action of HEPES has not been detected in previous studies as it had been tested on saturating (i.e. 100 µM) GABA concentrations (Dietrich and Morad, 2010). Four other buffering compounds, PIPES, MOPS, TRIS and imidazole, also inhibited GABAA receptors. PIPES and HEPES, two related piperazine derivatives, appeared as the most potent inhibitors. Such inhibition of GABAA receptors by HEPES and PIPES has been described for GABAergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) recorded in GCs but was interpreted as being – and seems in part – due to the limitation or suppression of the variation in endogenous pH (Dietrich and Morad, 2010). In the same study, MES had no effect on mIPSCs recorded in GCs (Dietrich and Morad, 2010). We also observed a lack of effect of MES on submaximal responses of GABAA receptors recorded on DH neurones in our experiments. Hydrogen ion buffers unrelated to piperazine derivatives (MOPS, TRIS and imidazole) also inhibited GABAA receptor-induced currents, but the observed inhibition was significantly weaker than with PIPES and HEPES and this difference might point to a distinct mechanism, not related to the buffering capabilities of these compounds.

Whereas the GABAA receptors of DH neurones appeared to be inhibited by protons when activated by submaximal concentrations of GABA, with 20 mM HEPES used to control the pHe, this apparent pH sensitivity was not observed under physiological buffering conditions (i.e. 26 mM HCO3-) in which pH changes were induced with controlled CO2/O2 ratios, suggesting that protonated HEPES rather than pH was involved in the inhibition of GABAA receptor function. This pH-dependent and HEPES-mediated inhibition of GABAA receptors can at first sight be (mis)interpreted as an H+-induced inhibition. The effect described in the present article should therefore be compared with the previously reported inhibitory effects of acidification on non-saturated GABAA receptors in presence of HEPES and related buffers. Importantly, the effect of HEPES was not sensitive to DEPC and was therefore clearly distinct from the H+-induced potentiation of GABAA receptors involving His267 of the β subunit as described and characterized by Wilkins et al. (2002). Indeed, our results show that HEPES did not inhibit GABAA receptor responses in DH neurones to saturating concentrations of GABA and that maximal responses of GABAA receptors are potentiated by protons under physiological buffering conditions. This effect is in agreement with the effect of acidification on maximally activated GABAA receptors, previously reported in other preparations under HEPES buffering (Pasternack et al., 1996; Krishek and Smart, 2001; Wilkins et al., 2002; Mozrzymas et al., 2003).

Interestingly, in the study of Wilkins et al. (2002), a pH-dependent inhibition of GABAA receptors was unmasked after DEPC treatment or in the case of the recombinant mutant receptor α1β1H267A, which has lost sensitivity to H+ after mutating His267 of the β subunit to an alanine (Wilkins et al., 2002). This apparent H+-induced inhibition was observed for GABA concentrations between 1 and 30 µM and was mostly observed at low pH values (Wilkins et al., 2002). This observation is compatible with our findings and might reflect the pH-dependent inhibitory effect of HEPES that we have observed, because in the experiments of Wilkins et al. (2002), external pH was controlled with 10 mM HEPES. Indeed, unlike the H+-induced potentiation of GABAA receptors that modulated both submaximal and maximal GABAA receptor responses, the apparent H+-induced inhibition concerned only submaximal GABAA receptor responses and could well correspond to the effect of HEPES described here. Moreover, an opposing pH sensitivity of GABAA receptors at low versus saturating concentrations of GABA has been described in various preparations when HEPES (10–20 mM) was used as the external pH buffer. In these studies, the apparent pH sensitivity observed at non-saturating GABA concentrations could well correspond to a pH-dependent HEPES-mediated inhibition of GABAA receptors. For example, in rat pyramidal neurones, H+ inhibited the currents induced by 5 µM GABA but potentiated those induced by 500 µM GABA (Pasternack et al., 1996), and in the same preparation, presumed non-saturating GABAergic mIPSCs were inhibited, whereas currents induced by saturating GABA applications were potentiated by protons (Mozrzymas et al., 2003). Similarly, the currents induced by application of 20 µM, but not 500 µM, GABA on recombinant α1β2γ2 and α3β2γ2 GABAA receptors were inhibited by acidic pH (Huang and Dillon, 1999). The pH sensitivity described in these studies for maximally activated GABAA receptors in the presence of extracellular HEPES is not likely to be explained by an effect of HEPES, because HEPES does not affect the maximal response of GABAA receptors. However, the H+-induced potentiation of submaximally activated GABAA receptors is likely to be underestimated in presence of extracellular HEPES. More critical is the question of H+-induced inhibition of GABAA receptors observed in various preparations at low agonist concentrations. Indeed, an increase of protonated HEPES concentration induced by lowering pH could contribute to a substantial fraction – if not the totality – of such effects, as we observed in DH neurones. As HEPES modulates submaximally activated GABAA receptors, the impact of HEPES might be particularly relevant for extrasynaptic receptors that are exposed to low concentrations of GABA, and particularly at low pH, when most of HEPES is protonated.

The mechanisms underlying the action of HEPES remain unclear. Nevertheless, because the maximal response of GABAA receptors was not changed by increasing HEPES concentration and because the effect of HEPES did not depend on the direction of current flow, HEPES-mediated inhibition was not caused by a channel-blocking action. Furthermore, the effect of HEPES did not depend on extracellularly accessible histidines and therefore did not involve His267 of the β subunit of GABAA receptors, the residue responsible for H+-induced potentiation (Wilkins et al., 2002).

Although a fraction of the effect of HEPES on GABA-induced current kinetics might be obscured by the solution exchange kinetics (that are only slightly faster than that of the faster GABA-induced currents in GCs), increasing HEPES concentration significantly slowed both the rising and the decaying phases of the currents induced by 30 µM GABA in both GCs and DH neurones. Such slower kinetics of non-saturating GABA-induced current in the presence of 20 mM HEPES are consistent with the effect of acidification observed in presence of HEPES in cultured hippocampal neurones, where these changes have been interpreted as a decrease in the binding rate of GABAA receptors (Mozrzymas et al., 2003). Importantly, in the same work, effects of acidification on saturating concentrations of GABA are unlikely to be explained by an antagonism of HEPES, as high concentrations of GABA were used (10 mM–30 mM), and these are unlikely to be challenged by HEPES (Mozrzymas et al., 2003).

In both DH neurones and GCs, increasing HEPES concentration did not change the amplitude and kinetics of currents induced by saturating concentrations of GABA, suggesting that HEPES blocked the currents induced by GABA in a competitive manner. In human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors expressed in CHO cells, HEPES similarly induced a rightward shift in the GABA concentration-response curve, and HEPES antagonism was surmountable when increasing the concentration of GABA. The similarity of maximum agonist response at different antagonist concentrations and the parallel rightward shift of the agonist dose-response curves with increasing antagonist concentrations are suggestive of a competitive inhibition of GABAA receptors by HEPES. However, the Schild regression analysis did not support a simple competitive behaviour of HEPES, as the slope of linear regression was significantly less than unity. The reason why the slope differed from unity is unclear and might suggest that one or more assumptions required in Schild analysis would not be applicable in the present case. We therefore used the simple ternary complex model for allosteric interaction described by Christopoulos and Kenakin (2002) to fit the GABA concentration-response data in presence of various concentrations of HEPES. The data were best fitted with a cooperativity factor α= 0.13 ± 0.03 denoting a negative cooperativity of GABA and HEPES and suggesting that HEPES inhibited the GABA-induced currents through an allosteric mechanism leading to a decrease in the apparent affinity for GABA.

Indeed, binding assays have clearly shown that millimolar concentrations of HEPES and other ‘Good buffers’ (Good et al. 1966), such as MOPS and PIPES, are competitive inhibitors of [3H]GABA- and [3H]muscimol-binding to rat brain synaptic membranes (Tunnicliff and Smith, 1981). Strikingly, our data indicate an inhibition constant for HEPES between 16 and 25 mM, which is close to the constant determined by Tunnicliff and Smith (1981) for the low-affinity component of [3H] muscimol binding (18 mM). Interestingly, as found by Tunnicliff and Smith (1981), HEPES, PIPES and MOPS, but not MES, were inhibitory on GABAA receptors.

When setting the criterion for selecting hydrogen ion buffers useful for biological research, Good et al. (1966) pointed out that these criteria correspond well to the characteristics of amino acids. Moreover, HEPES and PIPES are piperazine derivatives. Such compounds are known to bind to GABAA receptors (Jacobsen et al., 1999) and to inhibit the binding of GABA (Squires and Saederup, 1993). Possible non-buffer-related actions of HEPES have already been suggested in the horizontal cells of the salamander Ambystoma tigrinum retina, where switching between HCO3-/CO2-buffered and HEPES-buffered bath solution induced changes in the apparent effects of exogenously applied GABA (Hare and Owen, 1998). It is worth mentioning that non-buffer-related actions of ‘Good buffers’ are apparently not limited to inhibition of GABAA receptors. Indeed, HEPES blocks Cl--channels in Drosophila melanogaster (Yamamoto and Suzuki, 1987); MOPS, MES and PIPES hyperpolarize leech neurones (Schmidt et al., 1996), and HEPES prevents oedema in brain slices (MacGregor et al., 2001).

Our data clearly indicate that HEPES and related buffers should be used with extreme caution when exploring GABAA receptor function and should be avoided when the real/physiological sensitivity of GABAA receptors to protons is to be assessed, because HEPES-mediated pH-dependent inhibition might mask or truncate the direct H+-mediated modulation of these receptors. Finally, this pH-dependent modulation of submaximally activated, but not saturated, GABAA receptors by HEPES could also be a useful tool to discriminate between saturating and non-saturating GABAergic synapses.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Catherine Moreau and Chantal Fitterer for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université de Strasbourg, Institut UPSA de la Douleur and Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR).

Glossary

- DEPC

diethylpyrocarbonate

- DH

spinal cord dorsal horn

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAAR

GABAA receptors

- GCs

cerebellar granule cells

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- PIPES

piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)

- TRIS

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC) Br J PHARMACOL. (5th Edition) 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussouf A, Lambert RC, Gaillard S. Voltage-dependent Na(+)-HCO3-cotransporter and Na+/H+ exchanger are involved in intracellular pH regulation of cultured mature rat cerebellar oligodendrocytes. Glia. 1997;19:74–84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199701)19:1<74::aid-glia8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D, Feltz P, Schlichter R. Subpopulations of neonatal rat sensory neurons express functional neurotransmitter receptors which elevate intracellular calcium. Neuroscience. 1994;58:141–149. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Chesler M. Modulation of extracellular pH by glutamate and GABA in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:29–36. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Kenakin T. G protein-coupled receptor allosterism and complexing. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:323–374. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport CM, Detwiler PB, Dacey DM. Effects of pH buffering on horizontal and ganglion cell light responses in primate retina: evidence for the proton hypothesis of surround formation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:456–464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2735-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roo M, Rodeau JL, Schlichter R. Dehydroepiandrosterone potentiates native ionotropic ATP receptors containing the P2X2 subunit in rat sensory neurones. J Physiol. 2003;552:59–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH. Exocytosed protons feedback to suppress the Ca2+ current in mammalian cone photoreceptors. Neuron. 2001;32:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CJ, Morad M. Synaptic acidification enhances GABAA signaling. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16044–16052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6364-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good NE, Winget GD, Winter W, Connolly TN, Izawa S, Singh RM. Hydrogen ion buffers for biological research. Biochemistry. 1966;5:467–477. doi: 10.1021/bi00866a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare WA, Owen WG. Effects of bicarbonate versus HEPES buffering on measured properties of neurons in the salamander retina. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15:263–271. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898152069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RQ, Dillon GH. Effect of extracellular pH on GABA-activated current in rat recombinant receptors and thin hypothalamic slices. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1233–1243. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugel S, Schlichter R. Presynaptic P2X receptors facilitate inhibitory GABAergic transmission between cultured rat spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2121–2130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02121.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen EJ, Stelzer LS, TenBrink RE, Belonga KL, Carter DB, Im HK, et al. Piperazine imidazo[1,5-a]quinoxaline ureas as high-affinity GABAA ligands of dual functionality. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1123–1144. doi: 10.1021/jm9801307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YH, Stoeckel ME, Freund-Mercier MJ, Schlichter R. Oxytocin modulates glutamatergic synaptic transmission between cultured neonatal spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci. 1998a;18:2377–2386. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02377.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YH, Stoeckel ME, Schlichter R. Electrophysiological properties of cultured neonatal rat dorsal horn neurons containing GABA and met-enkephalin-like immunoreactivity. J Neurophysiol. 1998b;79:1583–1586. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Voipio J. Postsynaptic fall in intracellular pH induced by GABA-activated bicarbonate conductance. Nature. 1987;330:163–165. doi: 10.1038/330163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Saarikoski J, Voipio J. Mechanism of action of GABA on intracellular pH and on surface pH in crayfish muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1990;427:241–260. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Paalasmaa P, Taira T, Voipio J. pH transients due to monosynaptic activation of GABAA receptors in rat hippocampal slices. Neuroreport. 1992;3:105–108. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199201000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Voipio J, Paalasmaa P, Pasternack M, Deisz RA. The role of bicarbonate in GABAA receptor-mediated IPSPs of rat neocortical neurones. J Physiol. 1993;464:273–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishek BJ, Smart TG. Proton sensitivity of rat cerebellar granule cell GABAA receptors: dependence on neuronal development. J Physiol. 2001;530:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0219l.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishek BJ, Amato A, Connolly CN, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Proton sensitivity of the GABA(A) receptor is associated with the receptor subunit composition. J Physiol. 1996;492:431–443. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishtal OA, Pidoplichko VI. A receptor for protons in the nerve cell membrane. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2325–2327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor DG, Chesler M, Rice ME. HEPES prevents edema in rat brain slices. Neurosci Lett. 2001;303:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makani S, Chesler M. Endogenous alkaline transients boost postsynaptic NMDA receptor responses in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7438–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2304-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozrzymas JW, Zarnowska ED, Pytel M, Mercik K. Modulation of GABA(A) receptors by hydrogen ions reveals synaptic GABA transient and a crucial role of the desensitization process. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7981–7992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-07981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MJ, Hull C, Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. Synaptic cleft acidification and modulation of short-term depression by exocytosed protons in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11332–11341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11332.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternack M, Smirnov S, Kaila K. Proton modulation of functionally distinct GABAA receptors in acutely isolated pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robello M, Baldelli P, Cupello A. Modulation by extracellular pH of the activity of GABAA receptors on rat cerebellum granule cells. Neuroscience. 1994;61:833–837. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J, Mangold C, Deitmer J. Membrane responses evoked by organic buffers in identified leech neurones. J Exp Biol. 1996;199:327–335. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires RF, Saederup E. Mono N-aryl ethylenediamine and piperazine derivatives are GABAA receptor blockers: implications for psychiatry. Neurochem Res. 1993;18:787–793. doi: 10.1007/BF00966774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykova E. Extracellular pH and ionic shifts associated with electrical activity and pathological states in the spinal cord. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. Ph and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis R. pH modulation of ligand-gated ion channels. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. Ph and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnicliff G, Smith JA. Competitive inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor binding by N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-e-ethanesulfonic acid and related buffers. J Neurochem. 1981;36:1122–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voipio J, Pasternack M, Rydqvist B, Kaila K. Effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid on intracellular pH in the crayfish stretch-receptor neurone. J Exp Biol. 1991;156:349–360. doi: 10.1242/jeb.156.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins ME, Hosie AM, Smart TG. Identification of a beta subunit TM2 residue mediating proton modulation of GABA type A receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5328–5333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D, Suzuki N. Blockage of chloride channels by HEPES buffer. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1987;230:93–100. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]