Abstract

Low handgrip strength has been linked with premature mortality in diverse samples of middle-aged and elderly subjects. The value of handgrip strength as marker of “exceptional” human longevity has not been previously explored. We postulated that the genetic influence on extreme survival might also be involved in the muscular strength determination pathway. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the muscle strength in a sample of middle-aged adults who are genetically enriched for exceptional survival and comparing them to a control group. We included 336 offspring of the nonagenarian from the Leiden Longevity Study who were enriched for heritable exceptional longevity, and 336 of their partners were used as controls. The Leiden Longevity study was a prospective follow up study of long-living siblings pairs together with their offspring and their partners. Handgrip strength was used as a proxy for overall muscle strength. No significant difference in handgrip strength was seen between the offspring of the nonagenarian and their partners after adjustment for potential confounders including body compositions, sum score of comorbidities, medication use, smoking and alcohol history. The main determinants of midlife handgrip strength were age, gender, total body percentage fat and relative appendicular lean mass. Although midlife handgrip strength has previously been shown to be an important prognostic indicator of survival, it is not a marker of exceptional familial longevity in middle-aged adults. This finding suggests that genetic component of susceptibility to extreme survival is likely to be separate from that of muscular strength.

Keywords: Handgrip strength, Ageing, Sarcopenia, Familial longevity, Muscle

Introduction

Decline in muscle strength and function are well known consequences of the aging process (Forrest et al. 2005, 2007; Samson et al. 2000). Poor muscular strength has been consistently shown to be a prognostic indicator of important future outcomes such as physical disability (Giampaoli et al. 1999; Rantanen et al. 2002), and mortality in healthy middle-aged and elderly adults (Metter et al. 2002; Takata et al. 2007). The weakening of muscle with age is largely ascribed to the loss of skeletal muscle mass (Newman et al. 2003; Roubenoff and Hughes 2000), and the concomitant deterioration in muscle quality (Madsen et al. 1997; Metter et al. 1999) resulting from the degeneration of muscle fibres. There are, however, considerable inter-individual differences in physical strength and the rate of strength decline, due to variation in genetics and environmental influences (Tiainen et al. 2009; Carmelli and Reed 2000).

Handgrip strength is commonly used as an indicator of overall body strength (Bohannon 2001; Innes 1999), and it has been shown to be inversely associated with survival (Bohannon 2008; Ling et al. 2010). The heritability of handgrip strength has been previously observed but its reported estimates vary substantially (Tiainen et al. 2004; Reed et al. 1991; Arden and Spector 1997; Frederiksen et al. 2002). To our knowledge, handgrip strength has not been examined as a potential functional marker of exceptional human longevity in middle-aged subjects. We postulated that the genetic influence on longevity might also be involved in muscular strength determination pathway. As longevity is a heritable trait (Herskind et al. 1996; McGue et al. 1993), offspring of long-lived individuals present as a useful model in examining this relationship. We hypothesized that these individuals who are genetically enriched for familiar longevity will also have an innate benefit manifested as better muscle strength at middle age. Therefore, we compared the mid-life handgrip strength in a sample of offspring of nonagenarian to their partners with whom their share adult environment.

Methods

Study sample

Data were obtained from the Leiden Longevity Study, where long-lived siblings were recruited together with their offspring and the partners of their offspring. Families were eligible for the studies if (1) at least two long-lived, full siblings were alive, where men were considered long-lived if there were 89 years or older and women if they were 91 years and older and (2) the parents of the sibships were of Dutch descent. Further information on the design of the study and characteristics of the cohort has been published elsewhere (Schoenmaker et al. 2006).

For the current analysis, we included 336 offspring and 336 partners of the offspring from whom reliable handgrip strength and body composition measurements were obtained. The offspring of the nonagenarian siblings have been previously shown to have a survival benefit, with an on average 30% lower mortality rate compared to their birth cohort (Schoenmaker et al. 2006). Some of the favorable survival features seen in these offspring include lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome (Rozing et al. 2010a), better glucose tolerance (Rozing et al. 2010a), and cellular resistance to stress (Dekker et al. 2009). The partners of the offspring were used as matched controls and were of similar age sharing the adult environment with the offspring. The Medical Ethical Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Muscle strength assessment

Handgrip strength of the dominant side was measured (to the nearest kilogram) using a Jamar hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston Inc., Bolingbrook, IL) with the participants in an upright position. Participants were advised to exert maximal force and one test trial was allowed, followed by three test measurements. The best measure recorded was taken for the final analysis.

Potential confounders

Body composition

Upon entry into study, all subjects had measurements of their body weight and height. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight(kg)/height2(m). Body size was estimated by measuring body surface area (BSA) using the Mosteller formula (Mosteller 1987). Direct Segmental Multi-frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (DSM-BIA) was performed using the In-Body (720) body composition analyzer. We had previously shown this technique to be a valid tool for the assessment of whole body composition and segmental lean mass measurements in our sample of middle-aged population (Ling et al. 2011). The DSM-BIA technique employs the assumption that the human body is composed of five interconnecting cylinders and takes direct impedance measurements from the various body compartments. A tetrapolar eight-point tactile electrode system is used, which separately measures impedance of the subject’s trunk, arms, and legs at six different frequencies (1, 5, 50, 250, 500, 1,000 kHz) for each of the body segment. Total body weight (TBW) was estimated from area, volume, length, impedance and a constant proportion (specific resistivity). Lean mass was estimated as TBW/0.73. Body fat mass was calculated as the difference between TBW and lean mass. The machine gives immediate and extensive results including quantitative values of total body and segmental lean mass, fat mass and percentage fat mass. Appendicular lean mass (ALM) calculation was based on the sum of lean mass in both the right and left arms and legs. Relative ALM was calculated as ALM/body height2 (Janssen et al. 2002). The test was carried out by trained research nurses. Subjects wore normal indoor clothing and were asked to stand barefoot on the machine platform with their arms abducted and hands gripping on to the handles.

Other possible confounders

Information on common chronic diseases and medication use was obtained from the general practitioner, pharmacist’s records and blood sample analysis. Seven chronic diseases were documented including myocardial infarct, stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, neoplasm, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Medications were grouped into broad categories, which included cardiovascular medications (including antianginal, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics and lipid lowering medications), antithrombotic medications (including antiplatelets and anticoagulants), drugs for obstructive airway disease, anti-diabetic medications, other endocrine medications and nervous system medications (including opiates analgesics, anti-convulsants, anti-parkinsonian, anti-dementia, anti-migraines, sedatives, antipsychotics, antidepressants and anxiolytics). Unweighted sum scores for the total number of comorbid diseases and medication categories were used as indicators of burden and severity of diseases and were included as covariates. Indicators of thyroid function, measured by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (fT4), and free triiodothyronine (fT3) were also included. Health behavior variables included current smoking status and excessive alcohol use (male >210 g/week; female >140 g/week).

Statistical analysis

Means and medians between offspring and partners of the offspring within each gender were compared using t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test, respectively. Cross-tabulation with χ 2 test was used to compare proportion of offspring and partners of the offspring with comorbidities, use of various medication categories, smoking and excessive alcohol use. Pearson’s correlations were first used to study the association between handgrip strength and the potential continuous explanatory variables. Linear regression analysis was used to determine the association between handgrip strength with the offspring/partner of the offspring status, adjusted for age and gender. In addition, a linear regression model with age×gender and age×offspring/partners of offspring status interaction terms was constructed to determine whether the relationship between handgrip strength to age differed between the genders and the offspring/partners of the offspring, respectively. In the final multiple linear regression model, the terms included were age, gender, age×gender interaction term, offspring/partners of offspring status, body composition measurements including relative ALM and total body percentage fat mass, sum score of comorbidities, sum score of medication categories, fT3, current smoking status and the use of excess alcohol. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), version 17.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of the 672 subjects in the study are presented in Table 1. The female offspring were significantly older than the female partners of the offspring (62.9 years [SD, 5.9] vs. 60.7 years [SD, 6.9], respectively; p = 0.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of their comorbid diseases. There were more female partners of the offspring who were current smokers compared to the female offspring. For the males, the offspring were significantly younger than the partners of the offspring (63.6 years [SD, 6.0] vs. 65.4 years [SD, 6.9], respectively; p = 0.013). There were significantly more partners of the offspring with diagnosis of diabetes mellitus compared to the offspring (14.6% vs. 4.9%, respectively). Moreover, greater proportions of the male partners of the offspring were taking various categories of medications.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the offspring vs. partners of the offspring according to gender

| Variables | Female (N = 339) | Male (N = 333) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offspring (N = 153) | Partners (N = 186) | Offspring (N = 183) | Partners (N = 150) | |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 62.9 (5.9) | 60.7 (6.9) | 63.6 (6.0) | 65.4 (6.9) |

| Comorbidities (%) | 34.1 | 42.1 | 37.3 | 46.3 |

| Myocardial infarct | 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 6.1 |

| Stroke | 0.7 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 3.0 |

| Hypertension | 27.8 | 31.1 | 24.8 | 30.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.1 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 14.6 |

| Neoplasm | 6.8 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.3 | 4.2 | 6.7 | 3.1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| Sum score of comorbidities (median, IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Medication categories (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 30.9 | 31.2 | 24.6 | 46.7 |

| Anti-thrombotic | 5.1 | 6.5 | 10.5 | 18.5 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5.1 | 5.9 | 4.1 | 1.5 |

| Anti-diabetics | 2.2 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 10.4 |

| Other endocrine medications | 8.1 | 5.9 | 0.6 | 2.2 |

| Nervous system | 19.9 | 14.7 | 9.4 | 12.6 |

| Sum score of medication categories (median, IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) |

| Current smoking (%) | 7.4 | 15.6 | 13.8 | 13.1 |

| Excessive alcohol use (%) | 12.8 | 16.1 | 27.5 | 30.1 |

| Thyroid function | ||||

| TSH, mU/l (median, IQR) | 1.8 (1.1–2.7) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) |

| fT3, pmol/l (mean, SD) | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.6) |

| fT4, pmol/l (mean, SD) | 15.3 (2.5z) | 15.0 (2.6) | 15.5 (2.3) | 15.6 (1.9) |

Body compositions and handgrip strength measurements of the offspring vs. partners of the offspring according to gender are shown in Table 2. The female offspring had smaller BMI and BSA compared to their partners of the offspring counterparts. Consequently, they also had smaller absolute total body lean mass and fat mass, but no significant differences were noted in these parameters when adjusting for total body mass. The unadjusted handgrip strength for the female offspring was significantly lower compared to female partners of the offspring (28.8 kg [SEM, 0.4] vs. 30.3 kg [SEM, 0.4]; p = 0.01). This may be partly explained by their significantly older age and smaller body size. For the males, no significant offspring/partners of the offspring difference in body composition measurements and handgrip strength were observed.

Table 2.

Body compositions and handgrip strength measurements of the offspring vs. partners of the offspring according to gender

| Female (N = 339) | p Value | Male (N = 333) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offspring (N = 153) | Partners (N = 186) | Offspring (N = 183) | Partners (N = 150) | |||

| Anthropometrical measurements | ||||||

| Height (cm) | 165.4 (0.5) | 166.4 (0.4) | 0.11 | 178.3 (0.5) | 178.1 (0.6) | 0.80 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.3 (1.0) | 74.3 (1.0) | 0.00 | 86.0 (0.8) | 85.1 (1.0) | 0.48 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 (0.4) | 26.8 (0.3) | 0.04 | 27.0 (0.2) | 26.8 (0.3) | 0.60 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.79 (0.01) | 1.85 (0.01) | 0.00 | 2.06 (0.01) | 2.05 (0.01) | 0.44 |

| BIA estimates of whole body measurements | ||||||

| Lean mass (kg) | 45.5 (0.4) | 47.2 (0.4) | 0.00 | 63.6 (0.5) | 62.7 (0.6) | 0.24 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 24.8 (0.7) | 27.0 (0.7) | 0.04 | 22.3 (0.6) | 22.4 (0.6) | 0.96 |

| Percentage fat mass (%) | 34.5 (0.6) | 35.4 (0.6) | 0.22 | 25.5 (0.5) | 25.8 (0.5) | 0.69 |

| Appendicular lean massa (kg) | 20.2 (0.4) | 20.6 (0.3) | 0.27 | 25.6 (0.3) | 25.3 (0.4) | 0.56 |

| Relative appendicular lean mass† (kg/m2) | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | 0.71 | 8.0 (0.1) | 8.0 (0.1) | 0.74 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 28.8 (0.4) | 30.3 (0.4) | 0.01 | 47.5 (0.6) | 46.2 (0.7) | 0.15 |

Values are mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, BIA bioimpedance analysis

aSum measurements of lean mass in all four limbs

bAppendicular lean mass adjusted for height (appendicular lean mass/height2)

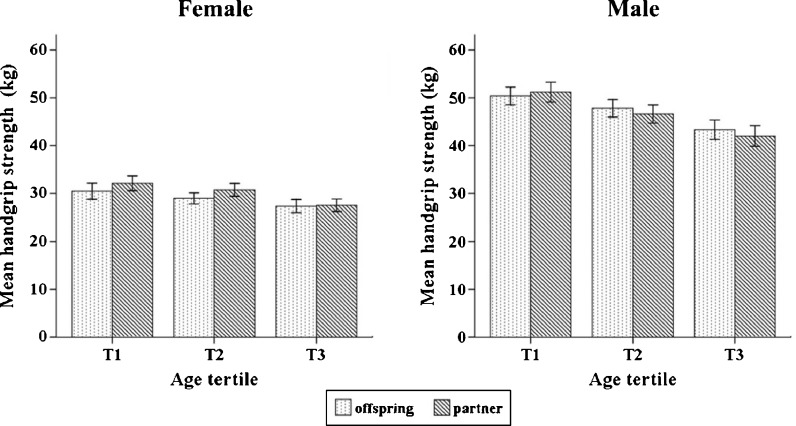

Figure 1 shows the mean handgrip strength of the offspring vs. partners of the offspring according to gender-specific age tertiles. The unadjusted handgrip strength for the female offspring was lower compared to their female counterparts at all age tertiles. Similar findings were seen in the males in the lowest age tertile (range, 45–62 years) but at higher ages (range, 62–83 years), male offspring were stronger compared to their counterparts. However, in the final multiple regression model (Table 3) where all potential covariates were included (adjusted R2 of model = 0.698, p < 0.001), the offspring/partners of the offspring status was not significant (p = 0.832). The main explanatory variables in the model were age, gender, whole body percentage fat mass (all p < 0.001) and relative ALM (p = 0.030).

Fig. 1.

Mean handgrip strength of the offspring vs. partners of the offspring according to gender-specific age tertiles. Age tertile (female)/(male), years: T1 = (39–59)/(45–62); T2 = (59–64)/(62–67); T3 = (64–79)/(67–83). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression models showing the association between handgrip strength and offspring vs. partners of the offspring status

| Handgrip strength (kg) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ||

| Model 1 | |||

| Offspring/partnersa | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.994 |

| Age (years) | −0.44 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Genderb | 18.47 | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Offspring/partners | 6.67 | 4.82 | 0.167 |

| Age (years) | −0.30 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 29.08 | 3.42 | <0.001 |

| Gender×age interaction | −0.17 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Offspring/partners×age interaction | −0.10 | 0.08 | 0.179 |

| Model 3 | |||

| Offspring/partners | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.832 |

| Age (years) | −0.26 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 32.21 | 5.32 | <0.001 |

| Gender×age interaction | −0.25 | 0.08 | 0.003 |

| Body composition | |||

| Relative appendicular lean mass (kg/m2) | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.030 |

| Whole body percentage fat mass (%) | −0.18 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Sum score of comorbidities | −0.67 | 0.45 | 0.136 |

| Sum score of medication categories | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.139 |

| Thyroid function test, fT3 (pmol/l) | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.675 |

| Current smoking | −0.92 | 0.82 | 0.267 |

| Excessive alcohol use | −0.32 | 0.68 | 0.639 |

B unstandardized regression coefficients, SE standard error

aOffspring = 0, partners = 1

bfemale = 0, male = 1

Discussion

The present study assessed the handgrip strength in a sample of middle-aged offspring of nonagenarian with familial longevity, and found no significant association between the offspring status and mid-life handgrip strength after adjusting for other potential confounders. The main determinants of handgrip strength were age, gender, total body percentage fat and relative ALM.

Handgrip strength has been shown to be a significant predictor of longevity, not only in the diseased but also in healthy middle-aged and older adults (Bohannon 2001). However, its value as a functional marker of life span in middle-aged adults with exceptional familial longevity is unclear. The survival benefit of the families from the Leiden Longevity Study is marked by a 30% decreased mortality risk observed in the survival analysis of three generations, i.e., the parents of the sibling pairs, their deceased additional siblings and their offspring (Schoenmaker et al. 2006). The familial survival advantage thereby exceeds the increased lifespan expectancy in the last generations of western societies due to genetic or familial factors (Westendorp et al. 2009). The offspring of the long-lived siblings further have a lower prevalence of diabetes, myocardial infarction, hypertension (Westendorp et al. 2009), better insulin sensitivity (Wijsman et al. 2011) and glucose handling (Rozing et al. 2011), a different lipid metabolism (Vaarhorst et al. 2011), a lower thyroidal sensitivity to thyrotropin (Rozing et al. 2010b) and also use less medication for cardiovascular disease as compared with their partners, with whom they have shared decades of common environment (Westendorp et al. 2009). The contrast between the offspring of nonagenarian siblings and their partners was also found to be reflected by cellular characteristics in vitro (Dekker et al. 2009, 2011; Derhovanessian et al. 2010).

In the present study, we postulated that these offspring would have superior muscle properties that would manifest as stronger muscle strength. Consequently, this would provide these individuals with a greater safety margin of muscle strength above the survival threshold later in life which contributes to their exceptional longevity. However, the findings of our study suggest that the genetic influence of longevity in these offspring is likely to be separate from that of muscular strength. Moreover, physical capacity is a complex trait influenced by intricate gene–environment interactions which can be challenging to disentangle. The reported heritability estimates for handgrip strength in twin studies varied substantially depending on the selected samples. In a study of 1,757 Danish twin pairs aged 45–96 years, Frederiksen et al. (2002) found a handgrip strength heritability of 52%. In contrast, another smaller study involving 199 Finnish female twin pairs aged 63–76 years, the hereditary estimate of handgrip strength was reported to be only 14% (Tiainen et al. 2004). Recently the pattern of transmission through the paternal and maternal line was studied in parent offspring pairs. Overall, a weak association of parental and offspring handgrip strength was found. A stronger relation was found between offspring and paternal but not maternal handgrip strength suggesting a sex-specific transmission (Cournil et al. 2010). A number of genetic variants have been identified affecting muscle strength in middle and old age (Arking et al. 2006; Crocco et al. 2011; De Mars et al. 2007; Ronkainen et al. 2008; Roth et al. 2001; Walsh et al. 2008, 2009). However, within our population it is unlikely that theses gene variants are differently expressed in offspring and partners.

Hence, it is plausible that the heritability component and the contribution of early life condition to handgrip strength in our study population are relatively small. On the other hand, transmissible environmental and positive lifestyle factors between the spouse pairs later in life such as exercise habits and healthy dietary intake have major roles on their strength determination.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to examine the association between midlife handgrip strength and exceptional familial longevity. The use of spousal controls in this study has the advantage of controlling for geographical background, birth cohort and adults socioeconomic environmental exposures and thus, enabling the identification of genetic contribution to muscle strength. However, we cannot rule out that we miss associations owing to assortative mating. There are limitations to our study. Firstly, we did not include any measures of physical activities in the final regression model due to unavailability of data. Assessments of burden and severity of diseases in this study were based on common comorbidities and medication categories. Thus, there might be other conditions associated with poor handgrip strength that we did not account for. Lastly, cross-sectional inference was used to estimate the age-related decline in handgrip strength which might not be comparable to longitudinal estimations. Continued follow-up of these spouse pairs might provide further insight into possibility of genetic contribution to handgrip strength later in life.

Conclusions

In summary, no difference in handgrip strength was found between middle-aged adults with and without history of familial longevity. Hence, we conclude that a middle adulthood handgrip measurement, which is representative of general muscle strength, is not a marker of exceptional familiar longevity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for scientific research (NGI/NWO; 05040202 and 050-060-810 NCHA) and the seventh framework programme MYOAGE (HEALTH-2007-2.4.5-10).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Arden NK, Spector TD. Genetic influences on muscle strength, lean body mass, and bone mineral density: a twin study. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:2076–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking DE, Fallin DM, Fried LP, Li T, Beamer BA, Xue QL, Chakravarti A, Walston J. Variation in the ciliary neurotrophic factor gene and muscle strength in older Caucasian women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:823–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW. Dynamometer measurements of hand-grip strength predict multiple outcomes. Percept Motil Skills. 2001;93:323–8. doi: 10.2466/pms.2001.93.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2008;31:3–10. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200831010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmelli D, Reed T. Stability and change in genetic and environmental influences on hand-grip strength in older male twins. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1879–83. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournil A, Jeune B, Skytthe A, Gampe J, Passarino G, Robine JM. Handgrip strength: indications of paternal inheritance in three European regions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1101–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocco P, Montesanto A, Passarino G, Rose G. A common polymorphism in the UCP3 promoter influences hand grip strength in elderly people. Biogerontology. 2011;12:265–71. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9321-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker P, Maier AB, van Heemst D, de Koning-Treurniet C, Blom J, Dirks RW, Tanke HJ, Westendorp RG. Stress-induced responses of human skin fibroblasts in vitro reflect human longevity. Aging Cell. 2009;75:595–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker P, de Lange MJ, Dirks RW, van Heemst D, Tanke HJ, Westendorp RG, Maier AB. Relation between maximum replicative capacity and oxidative stress-induced responses in human skin fibroblasts in vitro. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:45–50. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derhovanessian E, Maier AB, Beck R, Jahn G, Hähnel K, Slagboom PE, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Pawelec G. Hallmark features of immunosenescence are absent in familial longevity. J Immunol. 2010;185:4618–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mars G, Windelinckx A, Beunen G, Delecluse C, Lefevre J, Thomis MA. Polymorphisms in the CNTF and CNTF receptor genes are associated with muscle strength in men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:1824–31. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00692.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest KY, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA. Patterns and determinants of muscle strength change with aging in older men. Aging Male. 2005;8:151–6. doi: 10.1080/13685530500137840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest KY, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA. Patterns and correlates of muscle strength loss in older women. Gerontology. 2007;53:140–7. doi: 10.1159/000097979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen H, Gaist D, Petersen HC, Hjelmborg J, McGue M, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Hand grip strength: a phenotype suitable for identifying genetic variants affecting mid- and late-life physical functioning. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;23:110–22. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampaoli S, Ferrucci L, Cecchi F, LoNoce C, Poce A, Dima F, Santaquilani A, Vescio MF, Menotti A. Hand-grip strength predicts incident disability in non-disabled older men. Age Ageing. 1999;28:283–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskind AM, McGue M, Holm NV, Sorensen TI, Harvald B, Vaupel JW. The heritability of human longevity: a population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870–1900. Hum Genet. 1996;97:319–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02185763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes E. Handgrip strength testing: a review of the literature. Aust Occup Ther J. 1999;46:120–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;75:889–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling CH, Taekema D, de Craen AJ, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Maier AB. Handgrip strength and mortality in the oldest old population: the Leiden 85-plus study. CMAJ. 2010;182:429–35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling CH, de Craen AJ, Slagboom PE, Gunn DA, Stokkel MP, Westendorp RG, Maier AB (2011) Accuracy of direct segmental multi-frequency bioimpedance analysis in the assessment of total body and segmental body composition in middle-aged adult population. Clin Nutr [DOI] [PubMed]

- Madsen OR, Lauridsen UB, Hartkopp A, Sorensen OH. Muscle strength and soft tissue composition as measured by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in women aged 18–87 years. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1997;75:239–45. doi: 10.1007/s004210050154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Vaupel JW, Holm N, Harvald B. Longevity is moderately heritable in a sample of Danish twins born 1870–1880. J Gerontol. 1993;48:B237–44. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.6.b237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metter EJ, Lynch N, Conwit R, Lindle R, Tobin J, Hurley B. Muscle quality and age: cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B207–18. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.5.B207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metter EJ, Talbot LA, Schrager M, Conwit R. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:B359–65. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.B359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosteller RD. Simplified calculation of body surface area. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710223171717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Goodpaster B, Harris T, Kritchevsky S, Nevitt M, Miles TP, Visser M. Strength and muscle quality in a well-functioning cohort of older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:323–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Avlund K, Suominen H, Schroll M, Frandin K, Pertti E. Muscle strength as a predictor of onset of ADL dependence in people aged 75 years. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed T, Fabsitz RR, Selby JV, Carmelli D. Genetic influences and grip strength norms in the NHLBI twin study males aged 59–69. Ann Hum Biol. 1991;18:425–32. doi: 10.1080/03014469100001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen PH, Pöllänen E, Törmäkangas T, Tiainen K, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Rantanen T, Sipilä S, Kovanen V. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism is associated with skeletal muscle properties in older women alone and together with physical activity. PLoS One. 2008;3(3):e1819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubenoff R, Hughes VA. Sarcopenia: current concepts. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M716–24. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.M716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth SM, Schrager MA, Ferrell RE, Riechman SE, Metter EJ, Lynch NA, Lindle RS, Hurley BF. CNTF genotype is associated with muscular strength and quality in humans across the adult age span. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1205–10. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing MP, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Frölich M, de Goeij MC, Heijmans BT, Beekman M, Wijsman CA, Mooijaart SP, Blauw GJ, Slagboom PE, van Heemst D. Favorable glucose tolerance and lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in offspring without diabetes mellitus of nonagenarian siblings: the Leiden longevity study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:564–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing MP, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Slagboom PE, Beekman M, Frölich M, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, van Heemst D. Familial longevity is associated with decreased thyroid function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4979–84. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing MP, Mooijaart SP, Beekman M, Wijsman CA, Maier AB, Bartke A, Westendorp RG, Slagboom EP, van Heemst D (2011) C-reactive protein and glucose regulation in familial longevity. Age (Dordr), Jan 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Samson MM, Meeuwsen IB, Crowe A, Dessens JA, Duursma SA, Verhaar HJ. Relationships between physical performance measures, age, height and body weight in healthy adults. Age Ageing. 2000;29:235–42. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmaker M, de Craen AJ, de Meijer PH, Beekman M, Blauw GJ, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG. Evidence of genetic enrichment for exceptional survival using a family approach: the Leiden Longevity Study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:79–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata Y, Ansai T, Akifusa S, Soh I, Yoshitake Y, Kimura Y, Sonoki K, Fujisawa K, Awano S, Kagiyama S, Hamasaki T, Nakamichi I, Yoshida A, Takehara T. Physical fitness and 4-year mortality in an 80-year-old population. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:851–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen K, Sipila S, Alen M, Heikkinen E, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Tolvanen A, Pajala S, Rantanen T. Heritability of maximal isometric muscle strength in older female twins. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:173–80. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00200.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen K, Sipila S, Kauppinen M, Kaprio J, Rantanen T. Genetic and environmental effects on isometric muscle strength and leg extensor power followed up for three years among older female twins. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1604–10. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91056.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaarhorst AA, Beekman M, Suchiman EH, van Heemst D, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Westendorp RG, Slagboom PE, Heijmans BT, On behalf of the project group and the Leiden Longevity Study (LLS) Group Lipid metabolism in long-lived families: the Leiden Longevity Study. Age (Dordr) 2011;33:219–27. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Liu D, Metter EJ, Ferrucci L, Roth SM. ACTN3 genotype is associated with muscle phenotypes in women across the adult age span. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1486–91. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90856.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Kelsey BK, Angelopoulos TJ, Clarkson PM, Gordon PM, Moyna NM, Visich PS, Zoeller RF, Seip RL, Bilbie S, Thompson PD, Hoffman EP, Price TB, Devaney JM, Pescatello LS. CNTF 1357 G ->A polymorphism and the muscle strength response to resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1235–40. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90835.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp RG, van Heemst D, Rozing MP, Frölich M, Mooijaart SP, Blauw GJ, Beekman M, Heijmans BT, de Craen AJ, Slagboom PE, Leiden Longevity Study Group Nonagenarian siblings and their offspring display lower risk of mortality and morbidity than sporadic nonagenarians: the Leiden Longevity Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1634–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijsman CA, Rozing MP, Streefland TC, le Cessie S, Mooijaart SP, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG, Pijl H, van Heemst D, Leiden Longevity Study group Familial longevity is marked by enhanced insulin sensitivity. Aging Cell. 2011;10:114–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]