Abstract

Effective methods to engineer the segmented, double-stranded RNA genomes of Reoviridae viruses have only recently been developed. Mammalian orthoreoviruses (MRV) and bluetongue virus (BTV) can be recovered from entirely recombinant reagents, significantly improving the capacity to study the replication, pathogenesis, and transmission of these viruses. Conversely, rotaviruses (RVs), which are the major etiological agent of severe gastroenteritis in infants and children, have thus far only been modified using single-segment replacement methods. Reoviridae reverse genetics techniques universally rely on site-specific initiation of transcription by T7 RNA polymerase to generate the authentic 5′ end of recombinant RNA segments, but they vary in how the RNAs are introduced into cells: recombinant BTV is recovered by transfection of in vitro transcribed RNAs, whereas recombinant MRV and RV RNAs are transcribed intracellularly from transfected plasmid cDNAs. Additionally, several parameters have been identified in each system that are essential for recombinant virus recovery. Generating recombinant BTV requires the use of 5′ capped RNAs and is enhanced by multiple rounds of RNA transfection, suggesting that translation of viral proteins is likely the rate-limiting step. For RV, the efficiency of recovery is almost entirely dependent on the strength of the selection mechanism used to isolate the single-segment recombinant RV from the unmodified helper virus. The reverse genetics methods for BTV and RV will be presented and compared to the previously described MRV methods. Analysis and comparison of each method suggest several key lines of research that might lead to a reverse genetics system for RV, analogous to those used for MRV and BTV.

1. Introduction

The viruses of the Reoviridae family are exemplars of classical virology. Historically, their segmented, double-stranded (ds) RNA genomes afforded extensive genetic studies through reassortment and mutational screens (1–3). As a consequence of the inability to modify the genomes of these viruses through recombinant DNA technology (reverse genetics), until recently much of the work to characterize the Reoviridae was obtained through genetic, biochemical, and structural studies. Within the last five years, the development of powerful reverse genetics techniques for several Reoviridae viruses has afforded new opportunities for the study of these viruses (4–8). Reverse genetics is a complementary method to other approaches, as it allows specific linkage between structure and function, or phenotype, and can also validate information obtained through forward genetic screens (5, 9). Furthermore, as many Reoviridae viruses are significant human and animal pathogens, reverse genetics methods provide a tool to investigate pathogenesis and transmission (10–12), and may aid in the development of new vaccine strains (13).

Three of the best studied Reoviridae viruses for which reverse genetics systems have been developed are mammalian orthoreovirus (MRV; genus Orthoreovirus), bluetongue virus (BTV; genus Orbivirus), and rotavirus (RV; genus Rotavirus). MRV and BTV each have a ten-segmented genome that encodes 11 to 13 proteins. The recently developed MRV and BTV reverse genetics methods allow selection-free recovery of viruses that are derived from ten recombinant-derived genome segments (4, 5). In contrast, the 11-segmented (encoding 11–12 proteins) RVs, which are the most medically relevant of the Reoviridae, are currently limited to strategies in which a single recombinant-derived segment is introduced into the eleven-segmented genome of a helper virus. Single-segment recombinant RV must be isolated using a selection strategy that disfavors replication or spread of the unmodified helper virus (6–8).

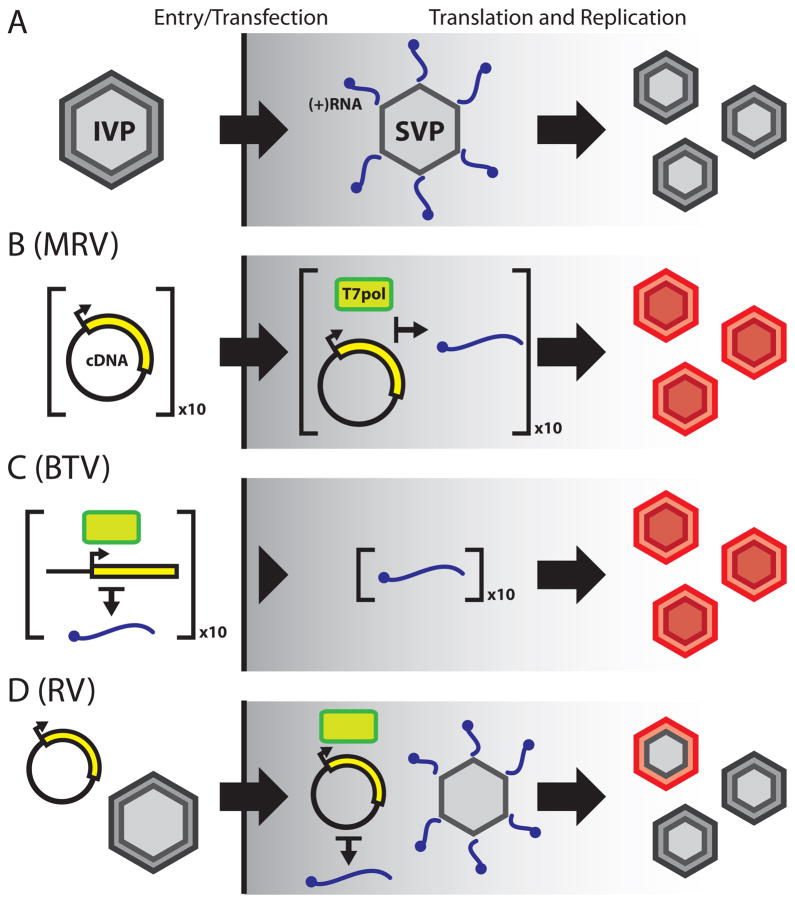

Although obvious differences exist in the replication mechanisms of each of the Reoviridae viruses, a common narrative can be applied to virtually all members of the family (Fig. 1A). (1) A multilayered, icosahedral virion binds to and enters a target cell. (2) Entry is associated with loss of the outermost capsid layer and delivers a ~70 nm subviral particle to the cytosol. (3) Internally packaged polymerase complexes transcribe and release capped, positive-sense RNAs ([+]RNAs) derived from each of the dsRNA segments. (4) These [+]RNAs function as both mRNAs for translation of viral proteins and templates for negative-sense RNA synthesis during dsRNA genome replication. (5) Viral nonstructural proteins establish large cytoplasmic inclusions that serve as sites of genome replication and particle assembly. (6) Release is primarily lytic, although both RV and BTV exit infected cells via exocytic trafficking under certain circumstances.

Figure 1. Comparison of Reoviridae reverse genetics methods with authentic virus replication.

(A) Schematic of Reoviridae virus replication. A multilayered, icosahedral infectious virus particle (IVP) binds and enters a target cell, prompting loss of the outer capsid. Once in the cytosol, the resulting subviral particle (SVP) becomes transcriptionally active and extrudes capped, [+]RNAs that serve as templates for viral protein synthesis and dsRNA genome replication. Viral inclusions are the sites of genome replication and nascent IVP assembly. (B) MRV reverse genetics. Ten plasmid cDNAs (corresponding to the ten MRV genome segments) are transfected into cells expressing T7 RNA polymerase (T7pol, green brick), wherein the cDNAs are transcribed into MRV [+]RNAs (blue squiggle). As with authentic virus, these [+]RNAs serve as templates for viral protein expression and dsRNA genome replication, resulting in formation of entirely recombinant IVPs (red). (C) BTV reverse genetics. Linearized plasmid cDNAs are transcribed in vitro using T7pol to generate a complement of the ten BTV [+]RNAs. The [+]RNAs are transfected into cells and are used for viral protein expression and virus replication to generate recombinant IVPs. (D) RV single-segment replacement. A plasmid cDNA encoding a single RV genome segment is transfected into cells expressing T7pol, followed by infection with a helper RV. Few helper virus particles incorporate the recombinant [+]RNA into their genome during replication, in place of the native species. This results in a virus population that is largely unmodified helper RV, but also contains a small population of single-segment recombinant RV (indicated by the red and grey IVP). Several selection strategies have been devised to isolate the single-segment recombinant RV from the helper virus.

The reverse genetics methods for MRV and BTV effectively bypass the stages of entry and introduce a full complement of recombinant [+]RNAs directly into the cytosol (Fig. 1B–C). Delivery of these [+]RNAs spontaneously, though perhaps infrequently (5), triggers downstream replication events and leads to the formation of fully infectious virions that can be amplified and recovered. Despite the evolutionary relatedness of the Reoviridae viruses, and the similarities between their replication mechanisms, the differences between MRV and BTV reverse genetics methods suggest that a single strategy to recover recombinant viruses may not exist for the Reoviridae. MRV is efficiently recovered by cDNA transfection into permissive cells and in situ transcription of [+]RNAs. There are no reports of this approach being used successfully to generate BTV. Instead, BTV recovery has relied on the transfection of in vitro-transcribed, capped [+]RNAs into permissive cells. Consequently, it is unclear whether a fully recombinant reverse genetics method for RV should parallel the method of MRV or BTV, or whether an altogether different strategy will be necessary. The current single-segment reverse genetics techniques for RV most closely resemble that of MRV (cDNA transfection followed by in situ transcription), but the involvement of a helper virus complicates extrapolation of this observation to a fully recombinant strategy (Fig. 1D). Here, we will briefly describe the reverse genetics methodology for MRV, which has recently been reviewed (14), and focus on those for BTV and the single-segment replacement systems for RV. It is our view that careful examination of the principles and techniques underlying each approach will enable efficient recovery of recombinant viruses and provide insight into alternative methodological approaches that may facilitate the development of a fully recombinant reverse genetics system for RV.

2. Overview of MRV reverse genetics

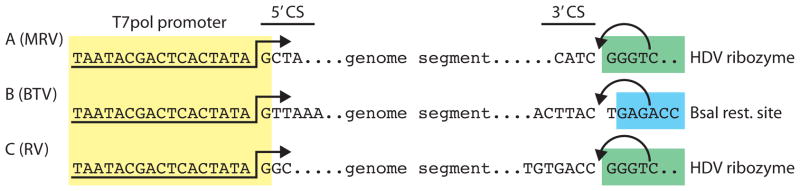

The cDNAs corresponding to each of the ten MRV [+]RNA segments are constructed such that a minimal T7 RNA polymerase (T7pol) promoter initiates transcription at a site corresponding to the authentic 5′ end (14) (Fig. 2A). The authentic 3′ end of each segment is generated by a cis-acting hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme; downstream of the ribozyme, T7pol transcription is halted by a terminator sequence (Fig. 2A). Recombinant-derived MRV can be recovered by infecting L929 murine fibroblast cells with the rDIs-T7pol strain of vaccinia virus, which has been engineered to express T7pol, followed by transfection with ten plasmids, each of which encodes a single viral genome segment (5). Two subsequent improvements to this method greatly enhance the recovery of recombinant MRV from reverse genetics experiments. First, multicistronic plasmids have been engineered to contain between two and four MRV cDNAs per plasmid, thus requiring transfection of four (rather than ten) separate plasmids to deliver the entire MRV genome (15). The enhanced co-transfection efficiency may result in a larger number of cells that initially generate infectious virus. Second, BHK-T7 cells, which stably express T7pol, are used in lieu of rDIs-T7pol to provide T7pol (15). Transfection of BHK-T7 cells with the MRV multicistronic plasmids permits recovery of more than 105 plaque-forming units (PFU) of recombinant MRV from a single reverse genetics experiment in as little as 48 h (15).

Figure 2. Reoviridae cDNA construction.

(A) A schematic of MRV cDNAs. A minimal T7 RNA polymerase (T7pol) promoter is used to generate the authentic 5′ end of each segment, including the 5′ consensus sequence (5′CS) present in all genome segments. The native 3′ end of each cDNA is generated by a hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme that is positioned to specifically cleave (arrow) after the 3′ consensus sequence (3′CS). A downstream T7pol terminator sequence (not shown) halts transcription after the HDV ribozyme sequence. (B) A schematic of BTV cDNAs. A minimal T7pol promoter is used to generate the authentic 5′ end and 5′CS, as with MRV. BTV plasmid cDNAs are linearized with a non-palindromic restriction enzyme positioned in the antisense orientation (BsaI is shown here, as an example) that cleaves the template cDNA strand immediately following the 3′CS. In vitro, run-off transcription by T7pol yields the correct 3′ end. (C) A schematic of RV cDNAs. RV cDNAs are constructed, and function, virtually identically to those of MRV (A).

3. Reverse genetics for BTV

3.1. Principles and theory

The fundamental principle of BTV reverse genetics, like that for MRV, is that the transcriptionally active subviral particle delivered during virus entry initiates viral replication by extruding [+]RNAs into the host cell cytosol. In practice, this is exactly how BTV reverse genetics works: the ten [+]RNAs constituting the BTV genome are infectious (4, 16) (Fig. 1C). Infectivity of BTV RNA was first demonstrated by recovery of infectious virus following transfection of highly purified in vitro transcribed [+]RNAs derived from isolated BTV subviral particles (16). This observation was then developed into a reverse genetics method through the construction of ten cDNAs encoding the BTV genome (4). Like that of MRV, BTV reverse genetics employs T7pol to generate the authentic 5′ end of each [+]RNA, but uses a run-off transcription mechanism (see section 3.2) to generate the native 3′ end (Fig. 2B). Importantly, this method is likely applicable to other Orbivirus species, as demonstrated by the generation of African horse sickness virus (AHSV) by transfection of purified, virus-derived [+]RNA transcripts into permissive cells (17).

A recurring theme for BTV reverse genetics is the importance of viral protein expression to efficiently generate recombinant virus. Transfection of a complement of [+]RNAs containing just a single uncapped segment effectively prevents recombinant BTV recovery (18). Why capped RNAs are required is not understood, although the presence of a cap most likely enhances translation from viral [+]RNAs in transfected cells. A critical technical advance for BTV reverse genetics came in the use of a “double-transfection” strategy, in which cells are transfected twice (separated by several hours) with BTV [+]RNAs; this approach significantly improves the efficiency of recombinant virus recovery (18, 19). This method may allow for the formation of BTV replication complexes (arising from viral proteins translated from the first set of transcripts) that then act on the second set of transcripts to initiate replication (18). Consistent with this interpretation, double-transfection experiments with AHSV strongly suggest that only the transcripts provided in the second transfection are replicated and give rise to recombinant progeny (17). Thus, [+]RNA capping and enhanced virus recovery by double-transfection highlight the importance of viral protein translation in BTV reverse genetics and indicate that it may be the rate-limiting step in the formation of infectious, recombinant virions.

3.2 Preparation of plasmids

BTV cDNAs are inserted into an empty plasmid (e.g., pUC19) along with a flanking T7pol promoter and a non-palindromic restriction site (4) (Fig. 2B). As with MRV reverse genetics, transcription by T7pol generates the authentic 5′ end of BTV [+]RNAs. Placement of the non-palindromic restriction site (those of BsmBI, BsaI, and BpiI have been used (4)) in the antisense orientation (downstream of the BTV cDNA) results in run-off transcription termination at the authentic 3′ end when the plasmid is appropriately digested (Fig. 2B).

Plasmids are digested according to the restriction enzyme manufacturer’s protocol and subsequently extracted once with phenol-chloroform and once with chloroform (4).

Each digested plasmid is precipitated with isopropanol and 0.15 M sodium acetate. The resulting DNA pellet is then washed twice with 70% (v/v) ethanol and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml (4).

3.3 In vitro transcription and capping

Transcripts containing a 5′ cap analog are synthesized from linearized BTV cDNAs with a mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra Kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s protocol. A 4:1 ratio of anti-reverse cap analog to rGTP is included in reaction mixtures (4).

The transcripts are purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by chloroform extraction. Unincorporated rNTPs are removed by gel filtration using Microspin G-25 columns (GE Healthcare) (4).

The T7 transcripts are concentrated by isopropanol precipitation in 0.15 M sodium acetate. The RNA is pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in a tabletop microcentrifuge. RNA pellets are washed twice with 70% ethanol and resuspended in sterile diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water.

Purified transcripts can be evaluated for concentration and purity by absorbance spectrophotometry (A260/A280) and/or denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis (20).

3.4 Transfection and virus recovery

BSR cells (ATCC #CCL-10) are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (complete DMEM-BSR) and incubated at 35°C in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2. One day before transfection, approximately 8 × 105 BSR cells are seeded into each well of a 12-well plate to yield confluent monolayers the following day (4, 18).

The initial transfection of T7 transcripts is performed as follows (18): Transcripts (50 ng each) that encode the BTV proteins VP1, VP3, VP4, VP6, NS1 and NS2 are combined in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) containing 0.5 U/μl RNasin Plus (Promega). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) is added to the sample and incubated at 20°C for 20 min. The transfection mixture is distributed evenly in a drop-wise manner to a single well of BSR cells. The cells are incubated at 35°C.

The second transfection is performed 18 h after the first (18). For this transfection, all ten BTV T7 transcripts (again, 50 ng each) are combined in Opti-MEM/RNasin Plus and mixed with Lipofectamine 2000. The BSR monolayer is transfected as in Step 2.

Six hours after the second transfection, the complete DMEM-BSR is removed, and the cells are overlayed with DMEM containing 2% (v/v) FBS and 1.5% (w/v) agarose. The cells are incubated at 35°C for three days to allow BTV plaques to develop in the BSR monolayer (greater than 50 plaques per transfection have been reported) (4, 18). BTV plaques can be isolated, and the recombinant virus amplified by standard techniques (16, 21, 22).

4. Single-segment reverse genetics for RV

4.1 Principles and theory

Anecdotally, the methods described above for MRV and BTV, when applied to RV, appear insufficient to generate recombinant virus (data not shown and P. Roy, personal communication). However, there are three methods to modify a single genome segment of RV that have been independently reported (6–8). For each, the process of generating recombinant RV is nearly identical: cells are infected with the vaccinia virus rDIs-T7pol, transfected with a single cDNA encoding the segment to be introduced into the RV genome, and infected with a helper RV to replicate and incorporate the recombinant segment (Fig. 1D).

The single-segment replacement methods for RV differ most significantly in the strategy used to isolate recombinant virus that is free of helper RV. The first reverse genetics method described for RV uses neutralizing antibody-based selection to isolate viruses with recombinant-derived segments encoding outer-capsid protein VP4 (6). It is difficult to estimate the efficiency of this method from published data, but it has been successfully used to study several aspects of VP4 biology, including neutralization and antigenicity properties of recombinant mosaic VP4 (23), and the site-specific proteolysis of VP4 during virion maturation (24). A second method exploits the preferential replication of genome segments containing partial head-to-tail duplications (“rearrangements”) that arise when RV is passaged at high multiplicity of infection (MOI) (8, 25). The specific mechanisms of how rearrangements arise naturally, and why they are preferential replicated during high MOI passage (26), are not known. In this reverse genetics method, a single segment encoding the NSP3 protein was engineered as a rearranged segment, and the recombinant RV bearing this segment was selected by passage at high MOI (8). Hypothetically, this method could be extended to any of the genome segments for which rearrangement has been observed (i.e., those encoding the VP6 (27), NSP1 (28), NSP3 (29), NSP4 (30), and NSP5 (31)). However, recovery of recombinant virus is very inefficient using this method. The selective pressure allows only a modest replication advantage for the recombinant, elongated segment; 18 rounds of selective passage yield a virus population that is nominally 50% recombinant (8). Furthermore, the RV genome can become unstable during serial passage at high MOI (formation of a rearranged segment, as defined here, is a type of genetic instability). Thus, this method has the potential to generate viruses containing adventitious mutations or additional genome rearrangements.

The most recently reported single-segment replacement method combines two independent selection mechanisms to rapidly isolate the recombinant RV (7). The helper RV (strain tsE) has a temperature-sensitive mutation in segment 8, which encodes the NSP2 replication-associated protein [2]. The mutation renders tsE incapable of replicating at 39°C. NSP2 is required for viral inclusion formation and, concordantly, RNAi-mediated knockdown of NSP2 protein expression severely inhibits viral replication (32). Therefore, passage at elevated temperature (first selection) in cells that have been genetically engineered to silence NSP2 expression through an shRNA mechanism (second selection) strongly restricts the helper tsE virus. By engineering an NSP2-encoding cDNA to correct the temperature-sensitive defect, and employing alternate codon usage to evade RNAi silencing, the resulting single-segment recombinant RV has a tremendous replication advantage over the helper RV. Two rounds of selective passage yield a population containing >105 PFU of virus, of which essentially 100% bears the single recombinant segment (7).

4.2 Propagation of the recombinant vaccinia virus, rDIs-T7pol

The vaccinia virus rDIs-T7pol is a severely restricted variant of the DIE strain that was engineered to expresses T7pol (33). rDIs-T7pol is incapable of replication in many mammalian cell types but nonetheless can cause significant cytopathic effect (CPE; data not shown). rDIs-T7pol is propagated in primary chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) and titered by TCID50 assay (34), or by functional titer in a reverse genetics experiment (described in section 4.5). A challenge when working with vaccinia virus is that it remains largely cell-associated, thus extensive sonication and multiple freeze-thaw cycles are required to effectively prepare virus stocks.

CEF cells are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml of amphotericin B (complete DMEM-CEF), at 37°C and 5% CO2. Thirty T-150 tissue-culture flasks are used to grow a total of 3 × 108 cells (reaching approximately 90% confluence).

Prior to infection, the rDIs-T7pol stock is processed in a bath sonicator to homogeneity (e.g., Misonix Sonicator 3000 with cup attachment). The rDIs-T7pol stock is sonicated for 1 min in ice water at power level 10 (output of approximately 90 W), and incubated on ice for 1 min. This sonication/incubation cycle is performed until the stock is nearly homogeneous, sometimes requiring more than 5 cycles for a fresh aliquot of virus stock.

Infection is performed at an MOI of 0.01 TCID50/cell in 5 ml of DMEM-CEF medium per T-150 flask. After a 1-h adsorption at 37°C, 20 ml of complete DMEM-CEF is added to each flask, which are then incubated at 37°C.

At 3–4 days post-infection (p.i.), when infection is characterized by focus formation and modest sloughing of the CEF monolayer, the cells are scraped into the medium and centrifuged at 2000 × g at 4°C for 5 min in 50 ml conical tubes. The supernatant is removed aseptically and reserved. Each pellet is then resuspended in 4.5 ml of reserved supernatant; the pellet suspensions are then pooled into three conical tubes (~150 ml total volume). The conical tubes are again centrifuged (as above) and the supernatants removed. The resulting pellets are used to prepare the rDIs-T7pol stock and can be stored at −80°C.

To prepare the rDIs-T7pol stock, the pellets are thawed and resuspended in 5 ml of Opti-MEM per conical tube. The pellet suspensions are pooled, frozen and thawed three times, sonicated (as above) for approximately six 1-min intervals, and frozen again.

The frozen suspension is thawed, sonicated twice, and clarified by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant is reserved (“supernatant 1”) and the pellet is resuspended in 15 ml of Opti-MEM.

The resuspended pellet is sonicated four times and clarified by centrifugation, as above. The supernatant (“supernatant 2”) is reserved. The resulting pellet can be stored at −80°C for troubleshooting purposes but should contain little recoverable vaccinia virus.

Supernatants 1 and 2 are pooled, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C (rDIs-T7pol stock). It is likely that the stock will contain some debris that will mostly resuspend in further sonication sessions (e.g., prior to infection).

rDIs-T7pol titer is determined by TCID50 assay (24), and verified by using serial dilutions in RV reverse genetics experiments to confirm functional recovery of recombinant RV (see sections 4.5 and 4.6).

4.3 Propagation of RV helper viruses

RV culture and quantification are standard techniques and have been described elsewhere (35). Virus strains thus far used in RV reverse genetics experiments are laboratory adapted and replicate well in cell culture. It is critical to amplify and titer temperature-sensitive helper RVs at the permissive temperature (typically 30–32°C). It also is helpful to titer temperature-sensitive RVs at the non-permissive temperature (typically 39°C) to validate the temperature-sensitive phenotype (36, 37).

4.4 Preparation of plasmids

Plasmid construction for each of the RV reverse genetics methods is essentially identical to that of MRV: a minimal T7pol promoter and an HDV ribozyme flank a full-length RV segment cDNA to produce RNAs with native 5′ and 3′ termini (Fig. 2C). The pBSmod plasmid contains an HDV ribozyme and T7pol terminator sequence immediately downstream of a SmaI (CCCGGG) restriction site that facilitates insertion of RV cDNAs (7). The short (17 nucleotides) upstream T7pol promoter sequence (Fig. 2C) is linked to the RV cDNA (e.g., by PCR) prior to insertion into the pBSmod vector. Bacteria transformed with pBSmod vectors can be cultured in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin (7). Plasmid DNA is isolated using a commercially available endotoxin-free purification kit (e.g., Qiagen EndoFree Maxi Prep Kit).

4.5 Transfection and infection with helper RV

COS-7 cells (ATCC #CRL-1651) are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (complete DMEM-COS), at 37°C and 5% CO2. One day prior to transfection, 1.25 × 106 COS-7 cells are seeded into 6-cm tissue-culture dishes in a final volume of 5 ml of complete DMEM-COS (one 6-cm dish is required for each plasmid transfection).

The cells should be nearly confluent and evenly dispersed on the day of transfection. A well-homogenized aliquot of rDIs-T7pol is used to infect the cells at an MOI of 3 TCID50/cell (typically 25–100 μl of virus stock per dish if the protocol in section 4.2 is followed). Cells are infected with rDIs-T7pol for 1 h at 37°C in 1 ml of Opti-MEM per dish on a rocking platform. (Note: After determining the TCID50 titer of the rDIs-T7pol stock, it is helpful to perform a reverse genetics experiment to validate the titer using volumes of inocula ranging from five-fold above and below the estimated titer [required for an MOI of 3]).

During the 1 h of rDIs-T7pol adsorption, plasmid transfection mixtures are prepared. For each sample, 500 μl of Opti-MEM at room temperature is dispensed into 1.5 ml snap-cap tubes. Fifteen μl of Trans-IT LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC) at room temperature is added to each tube; the mixture is then vortexed for 1–2 s. After addition of 5 μg of plasmid DNA (typically 2–10 μl) to each tube, the tubes are vortexed and quickly centrifuged using a tabletop microcentrifuge. The DNA-transfection reagent mixture is incubated at room temperature for 30 min. (Note: A plasmid encoding a fluorescent protein under the control of T7pol (e.g., pGLT7) (7) can be used as a control to evaluate the efficiency of rDIs-T7pol infection and transfection.)

After the 1-h adsorption, the COS-7 cells in each dish are washed once with 1 ml of complete DMEM-COS and then overlayed with 5 ml of complete DMEM-COS. Each transfection mixture (approximately 530 μl) is added to a separate dish, evenly and drop-wise. The dishes are gently rocked (not swirled) and incubated at 37°C for 20 h.

If a T7pol-reporter plasmid was included, the cells can be observed under a fluorescence microscope at 16–18 h p.i. Greater than 80% of cells should be intensely fluorescent in an ideal experiment (see section 5, Troubleshooting).

At 18–19 h post-transfection (p.t.), an aliquot of helper RV stock should be activated by incubating with 5 μg/ml of trypsin (final concentration) at 37°C for 1 h (using a stock solution (2 mg/ml) of tissue culture-grade, filter-sterilized trypsin, Type IX-S, 14,700 units/mg (Sigma)). At 20 h p.t., the complete DMEM-COS medium is removed from each dish, and the cells are washed twice with 2.5 ml of unsupplemented DMEM to remove serum and residual transfection reagent. The helper RV is added to each dish in 1 ml of unsupplemented DMEM at an MOI of 3 PFU/cell. The dishes are placed in a 37°C incubator and manually rocked at 15 min intervals for 1 h. (Note: Incubation at 30°C is recommended for this step if a temperature-sensitive RV is used.)

After the 1-h adsorption, the inoculum is removed and replaced with 2.5 ml of unsupplemented DMEM without trypsin, and the cells are returned to a 37°C incubator (30°C, if a temperature-sensitive helper RV is used). Trypsin is omitted here due to the significant CPE that occurs when added to COS-7 cells that have previously been infected (RV, rDIs-T7pol) and transfected. RV recovered from the COS-7 cells is trypsin activated prior to passage onto fresh cells (see section 4.6, step 2, below). At 24 h p.i., the cells are harvested by placing in a −80°C freezer.

It has been observed that reversing the order of rDIs-T7pol infection and cDNA transfection (steps 2–4 above) generates a larger population of COS-7 cells that are transfected and co-infected with rDIs-T7pol and the helper RV (8), but it is not clear whether this increases the recovery of recombinant RV. The authors have not tested this variant protocol, but it may be beneficial under conditions of weak selection against the helper RV.

4.6 Passage using selection to isolate recombinant RV

MA104 cells (ATCC #CRL-2378.1) are cultured in Medium 199 supplemented with 5% (v/v) FBS (complete M199), at 37°C and 5% CO2. Approximately 1.5 × 106 cells are seeded into one 10-cm dish per sample to be analyzed; the cells usually reach confluence in 2–3 days.

The viral supernatants (2.5 ml) obtained from section 4.5 are frozen and thawed twice to release virus from cellular debris. The supernatants are clarified by centrifugation at 2000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Trypsin is added to the clarified supernatant to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. The supernatant is incubated at 37°C in a water bath for 1 h. (Note: Incubation with trypsin ensures activation of RV virions, enhancing infectivity.)

The 10-cm dishes of confluent MA104 cells are washed twice with M199 (unsupplemented; no FBS) to remove the complete M199. (Note: FBS has potent anti-trypsin activity that reduces RV infectivity.)

After the M199 wash, each trypsin-treated viral supernatant is added to a 10-cm dish. The virus is adsorbed to the cells at 37°C for 1 h on a rocking platform.

After the 1-h adsorption, the supernatant is removed from each dish and replaced with 10 ml of M199 supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml of trypsin and 10 μM cytosine-β-D-arabinofuranoside HCl (araC; Sigma) and returned to a 37°C incubator. (Note: The inclusion of trypsin here promotes efficient cell-to-cell RV spread, while araC inhibits rDIs-T7pol replication.)

After complete CPE (approximately 3 d p.i.), the cells are harvested by two cycles of freezing at −80°C and thawing.

The number of rounds of selective passage required to isolate the recombinant RV is dependent on the selection mechanism employed. Serial passage can be performed by taking 5 ml of the supernatant obtained in step 6, clarifying and trypsin-treating (as in step 2), and passaging onto fresh monolayers of MA104 cells (steps 3–6). This process can be repeated as necessary.

The presence of recombinant RV in supernatants can be monitored using segment-specific primers, RT-PCR, and sequencing (7). Viral titers can be quantified by plaque assay. Single plaques can be picked to recover individual virus clones (35).

Several variations of this protocol are possible, depending on the selection strategy employed. Neutralizing antibody selection requires maintenance of purified, titered antibody in the medium of cells that are propagating RV (step 5) (5, 6). The dual-selection method uses an shRNA-expressing MA104 cell line (MA104-g8D) in lieu of “standard” MA104 cells and incubation at 39°C (step 5) (7). During each reverse genetics experiment, it is advisable to perform a mock transfection/helper-RV infection as a negative control to assess the effectiveness of the screening procedure (see section 5).

5. Troubleshooting

Many of the suggestions proposed for troubleshooting MRV reverse genetics experiments are also applicable to BTV reverse genetics and RV single-segment replacement (14). It is almost always advisable to include informative positive and negative controls in the experiment. For MRV and BTV, independent recovery of a wild-type (wt)-like recombinant virus in parallel with the mutant of interest serves to validate several aspects of the experiment (DNA/RNA preparations, cells, transfection reagent, etc.). Once adept at the technique, recovery of wt-like recombinant virus also can be semi-quantitative (i.e., was the wt-like virus recovered at the expected titer?). A useful negative control is the omission of a single cDNA plasmid (or RNA transcript), which should fail to generate recombinant virus. Alternatively, a cDNA plasmid (or RNA) can be substituted with a comparable one that expresses a fluorescent reporter, such as pGLT7, which encodes T7pol-transcribed GFP (7). This control permits validation of variables such as transfection efficiency and, for RV, infection by rDIs-T7pol.

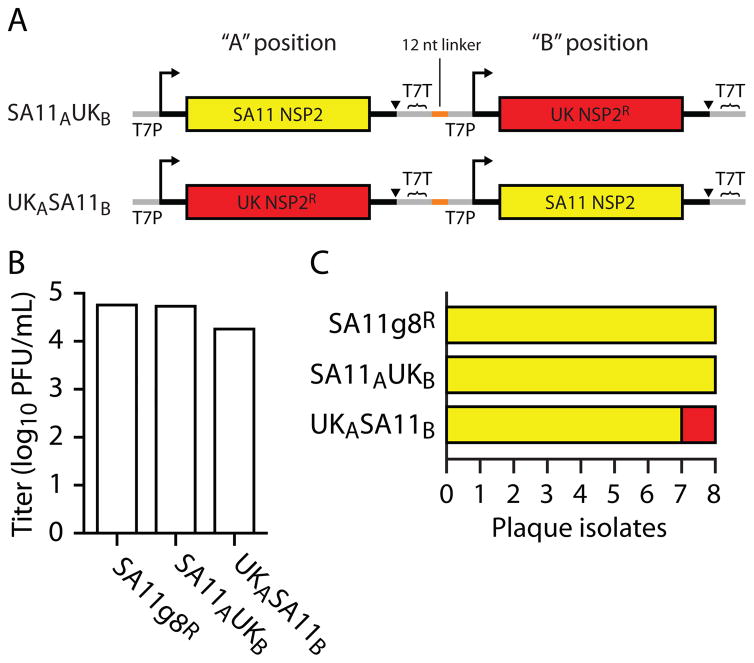

An alternative positive control that we have used for RV single-segment replacement involves constructing a bicistronic plasmid encoding both a wt-like and mutant version of the same genome segment (Fig. 3A). This strategy provides an internal positive control for recombinant RV recovery and allows some manner of comparison between the capacities of the wt-like and mutant segments to support RV replication. The caveat with this strategy is that the wt-like positive-control virus also directly competes with the recombinant mutant virus (Fig. 3B–C). In situations in which the mutant segment (here, UK) yields a virus with reduced replication capacity (small plaque phenotype) (7), we observe preferential recovery of virus containing the wt-like segment (SA11) (Fig. 3C). To bias recovery in favor of the mutant, we have observed that placement of the wt-like cDNA in the 3′ ”B” position improves recovery of mutant virus, although it remains a minor population (Fig. 3B–C). This technique is most effective if the single-segment recombinant RV has not been recovered using the “standard” controls described above. If not recoverable by the bicistronic plasmid method, we consider the mutant to be insufficiently replication-competent to be isolated by single-segment replacement.

Figure 3. Bicistronic, single-segment plasmids can function as an internal control in RV single-segment replacement experiments.

(A) Diagram of two bicistronic RV plasmids. The SA11AUKB construct has a wild-type (wt)-like SA11 strain (yellow) genome segment 8 (encoding the NSP2 protein) in the “A” position, a small linker, and a chimeric (mutant) segment 8 derived from the UK strain (red) in the “B” position. Each cDNA has its own T7 RNA polymerase promoter (T7P; crooked arrow), ribozyme (triangle), and T7 terminator sequence (T7T). The UKASA11B construct is similarly constructed, except that the UK segment 8 is in the A position, and the SA11 segment 8 in the B position. (B) Titers of recombinant virus from a reverse genetics experiment. Plasmids encoding the wt-like SA11 segment 8 (SA11g8R) or the two bicistronic plasmids were used to generate recombinant virus. After two rounds of selection using MA104-g8D cells cultured at 39°C (see sections 4.1 and 4.6, and reference (7)), viruses were titered using MA104 cells. RT-PCR and sequence analysis of the second-passage supernatants confirmed that each plasmid successfully generated single-segment recombinant RV (not shown). (C) Analysis of plaque isolates. Individual plaques (n=8 per sample) were isolated from the plaque assays performed in (B) and amplified in individual wells of a 12-well plate of MA104 cells. RT-PCR and sequence analysis allowed typing of the segment 8 from each isolate. The identities of the isolates are colored as in (A). Note that (i) recovery of UK recombinant virus is lower than SA11 in all cases and (ii) UKASA11B yields a lower titer of virus (B) but a higher frequency of UK virus (relative to SA11) (C), suggesting that placement of the mutant segment in the A position and wt-like control in the B position allows for more efficient isolation and recovery of the mutant virus.

6. Strategies to develop fully recombinant RV

Reverse genetics for MRV and BTV are effectively mature technologies. Both allow the facile and rapid recovery of wt-like and mutant viruses, so long as they are replication competent. Additionally, support cell lines that express one or more viral proteins have been used in both systems to recover viruses that are (on their own) replication incompetent, due to gene deletion or modification (5, 18). For BTV, this strategy has led to the development of a replication-incompetent vaccine candidate for this important veterinary pathogen (13). It was anticipated that the development of reverse genetics techniques for these viruses would precipitate development of a comparable technique for RV, thereby permitting previously untenable analyses of RV biology (including pathogenesis and transmission) and the development of recombinant vaccine strains. While fully recombinant RV has yet to be realized, several key insights garnered from MRV and BTV suggest several possible routes of experimentation.

The development of reverse genetic methods for two- and three-segmented dsRNA viruses (Birnaviridae and Cystoviridae) several years ago indicated that this group of viruses is amenable to sophisticated genetic manipulation (38, 39). Likewise, methods to recover infectious, recombinant MRV and BTV imply that a technical, rather than a biological, hurdle exists when attempting to generate fully recombinant RV. The similarities between MRV reverse genetics and RV single-segment replacement methods (compare Fig. 1B, D and Fig. 2A, C) suggest that it should be possible to achieve a fully recombinant RV reverse genetics system relying on transfection of 11 RV cDNA plasmids (into rDIs-T7 infected cells. However, experiments along this line have yet to be successful, even when instead of individual plasmids, a set of four multicistronic plasmids are transfected into the cells (data not shown). Several factors are commonly considered when evaluating this apparent failure:

RVs do not replicate as robustly as MRV. RVs can replicate to 108 PFU/mL, while most MRV strains are capable of replicating to >109 PFU/mL.

rDIs-T7pol (and other attenuated vaccinia viruses) cause significant CPE in most cell types used for RV culture.

Spread of RVs in cell culture requires removal of FBS and addition of trypsin, which reduces cell viability in the face of transfection and rDIs-T7pol infection.

Despite the issues, single-segment replacement indicates that RV [+]RNAs derived from recombinant cDNAs can be introduced into the RV replication cycle. One perpetual concern for reverse genetics systems is the presence of lethal mutations in the recombinant genome that would preclude recovery of infectious virus. Extensive analysis of RV proteins by biochemistry (40–42), structural analysis (43–45), complementation (32), and myriad other techniques, suggests that sequences used in plasmid-based reverse genetics experiments are correct. Additionally, RV genomics data have validated the non-coding sequences used in cDNA construction of all RV genome segments, most specifically the highly-conserved, segment-specific 5′ and 3′ consensus sequences thought to be essential for RNA packaging and replication (46–47) (Fig. 2C). It instead seems likely that the RV cDNAs are functional in principle, while a technical limitation, such as levels of RV protein expression or RNA transcription, prevents the formation of recombinant virus.

For BTV, expression of viral proteins (as indicated by the absolute requirement for RNA capping, and enhancement of recovery by double-transfection of replication-protein transcripts) is critical for generating recombinant virus (18). Expression of RV proteins may be the rate-limiting step to establishing replication in the absence of infection. Notably, single wt-like RV cDNAs (when transcribed by T7pol from rDIs-T7pol) fail to generate significant amounts of RV protein (7). Thus, modification of the cDNAs to enhance RV protein expression may be necessary to promote formation of replication complexes. One approach, the subtle modification of the RV cDNA 5′ consensus sequence, greatly increased the expression of a RV protein (NSP2), but also decreased the recovery of single-segment recombinant virus (7). Development of a strategy in which wt-like RV cDNAs are supplemented with constructs specifically engineered to express viral replication proteins appears to be a rational conclusion. This approach could consist of the simple addition of support plasmids (e.g., in a pCI or similar plasmid backbone) or through the development of dual support/cDNA plasmids analogous to those used for influenza A virus reverse genetics (48).

Interestingly, Lourenco and Roy [49] have recently described a cell-free reconstitution system that supports the assembly of infectious BTV core particles from in vitro synthesized viral [+]RNAs and proteins. This system provides an alternative, albeit much more complex, approach for generating recombinant BTV than that of simply transfecting 11 BTV [+]RNAs into permissive cells [4, 16, 18]. However, given the failure to establish a fully recombinant reverse genetics system for RV via transfection of T7-expression vectors or T7 [+]RNA transcripts into permissive cells, it may be worthwhile considering the alternative approach of using a BTV-like reconstitution system for producing recombinant RV.

Considering MRV and BTV reverse genetics, and single-segment replacement for RV, many tools are now in place to troubleshoot and advance reverse genetics for RV. However, it seems likely that there may not be a “universal” approach to reverse genetics for the Reoviridae viruses.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Arnold, M. Morelli, and K. Ogden for careful review of the manuscript. We thank T. Kobayashi and P. Roy for helpful conversations and sharing of unpublished data. This work was supported by Public Health Service award Z01 AI000788 from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (S.D.T. and J.T.P.), Public Health Service awards T32 CA09385 (K.W.B.), F32 AI075776 (K.W.B.), R01 AI32539 (T.S.D.), and R37 AI38296 from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fields BN, Joklik WK. Virology. 1969;37:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramig RF. Virology. 1982;120:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner HL, Drayna D, Averill DR, Jr, Fields BN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5744–5748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce M, Celma CC, Roy P. J Virol. 2008;82:8339–8348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00808-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T, Antar AA, Boehme KW, Danthi P, Eby EA, Guglielmi KM, Holm GH, Johnson EM, Maginnis MS, Naik S, Skelton WB, Wetzel JD, Wilson GJ, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komoto S, Sasaki J, Taniguchi K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4646–4651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509385103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trask SD, Taraporewala ZF, Boehme KW, Dermody TS, Patton JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18652–18657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011948107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troupin C, Dehee A, Schnuriger A, Vende P, Poncet D, Garbarg-Chenon A. J Virol. 2010;84:6711–6719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00547-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirchner E, Guglielmi KM, Strauss HM, Dermody TS, Stehle T. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000235. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ooms LS, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS, Chappell JD. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41604–41613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boehme KW, Guglielmi KM, Dermody TS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19986–19991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danthi P, Coffey CM, Parker JS, Abel TW, Dermody TS. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000248. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuo E, Celma CC, Boyce M, Viarouge C, Sailleau C, Dubois E, Breard E, Thiery R, Zientara S, Roy P. J Virol. 2011;85:10213–10221. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05412-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehme KW, Ikizler M, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS. Methods. 2011;55:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi T, Ooms LS, Ikizler M, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Virology. 2010;398:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyce M, Roy P. J Virol. 2007;81:2179–2186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01819-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo E, Celma CC, Roy P. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3386–3391. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo E, Roy P. J Virol. 2009;83:8842–8848. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00465-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratinier M, Caporale M, Golder M, Franzoni G, Allan K, Nunes SF, Armezzani A, Bayoumy A, Rixon F, Shaw A, Palmarini M. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002477. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertens PP, Burroughs JN, Anderson J. Virology. 1987;157:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forzan M, Marsh M, Roy P. J Virol. 2007;81:4819–4827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02284-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komoto S, Kugita M, Sasaki J, Taniguchi K. J Virol. 2008;82:6753–6757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00601-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komoto S, Wakuda M, Ide T, Niimi G, Maeno Y, Higo-Moriguchi K, Taniguchi K. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2914–2921. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hundley F, Biryahwaho B, Gow M, Desselberger U. Virology. 1985;143:88–103. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troupin C, Schnuriger A, Duponchel S, Deback C, Schnepf N, Dehee A, Garbarg-Chenon A. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen S, Burke B, Desselberger U. J Virol. 1994;68:1682–1688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1682-1688.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton JT, Taraporewala Z, Chen D, Chizhikov V, Jones M, Elhelu A, Collins M, Kearney K, Wagner M, Hoshino Y, Gouvea V. J Virol. 2001;75:2076–2086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2076-2086.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold MM, Brownback CS, Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT. J Gen Virol. 2012;93 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.041830-0. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard A, McCrae MA, Desselberger U. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:633–638. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-3-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima K, Taniguchi K, Kawagishi-Kobayashi M, Matsuno S, Urasawa S. Virus Res. 2000;67:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taraporewala ZF, Jiang X, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Jayaram H, Prasad BV, Patton JT. J Virol. 2006;80:7984–7994. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00172-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii K, Ueda Y, Matsuo K, Matsuura Y, Kitamura T, Kato K, Izumi Y, Someya K, Ohsu T, Honda M, Miyamura T. Virology. 2002;302:433–444. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isaacs SN. Vaccinia Virus and Poxvirology, Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Virology. Vol. 269. Humana Press Inc; Totowa, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold M, Patton JT, McDonald SM. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2009;Chapter 15(Unit 15C):3. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc15c03s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen D, Gombold JL, Ramig RF. Virology. 1990;1978:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gombold JL, Estes MK, Ramig RF. Virology. 1985;143:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mundt E, Vakharia VN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11131–11136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olkkonen VM, Gottlieb P, Strassman J, Qiao XY, Bamford DH, Mindich L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9173–9177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald SM, Patton JT. J Virol. 2011;85:3095–3105. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02360-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim IS, Trask SD, Babyonyshev M, Dormitzer PR, Harrison SC. J Virol. 2010;84:6200–6207. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02461-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogden KM, Ramanathan HN, Patton JT. J Virol. 2011;85:1958–1969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01689-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Settembre EC, Chen JZ, Dormitzer PR, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC. EMBO J. 2011;30:408–416. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X, McDonald SM, Tortorici MA, Tao YJ, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Nibert ML, Patton JT, Harrison SC. Structure. 2008;16:1678–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jayaram H, Taraporewala Z, Patton JT, Prasad BV. Nature. 2002;417:311–315. doi: 10.1038/417311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li W, Manktelow E, von Kirchbach JC, Gog JR, Desselberger U, Lever AM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7718–1135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trojnar E, Otto P, Roth B, Reetz J, Johne R. J Virol. 2010;84:10254–10265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00332-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Hobom G, Webster RG, Kawaoka Y. Virology. 2000;267:310–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lourenco S, Roy P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13746–13751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108667108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]