Abstract

Non-contrast-enhanced (NCE) magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a promising alternative to the established contrast-enhanced approach as it reduces patient discomfort and examination costs, and avoids the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Inflow-sensitive slab-selective (SS) inversion recovery (IR) imaging has been used with great promise, particularly for abdominal applications, but has limited craniocaudal coverage due to inflow time constraints. In this work, a new NCE MRA method using velocity-selective (VS) inversion preparation is developed and applied to renal and abdominal angiography. Based on the excitation k-space formalism and Shinnar-Le-Roux transform, a VS excitation pulse is designed that inverts stationary tissues and venous blood while preserving inferiorly flowing arterial blood. As the magnetization of the arterial blood in the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries is well-preserved during the magnetization preparation, artery visualization over a large abdominal FOV is achievable with an inversion delay time that is chosen for optimal background suppression. Healthy volunteer tests demonstrate that the proposed VS-IR MRA method significantly increases the extent of visible arteries compared with the SS-IR approach, covering renal arteries through iliac arteries over a craniocaudal FOV of 340 mm.

Keywords: non-contrast-enhanced MRA, velocity-selective magnetization preparation, renal and abdominal MRA, 3D balanced steady-state free precession

Introduction

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has evolved into a powerful diagnostic tool for arterial diseases due to its minimally invasive and non-toxic natures. The most established approach for MRA uses Gadolinium-based contrast agents and T1-weighted imaging sequences to generate hyperintense arterial signal. While the contrast-enhanced (CE) approach has shown excellent diagnostic performance in diverse applications (1–3), intravenous administration of contrast agents increases patient discomfort as well as examination costs, and limits the achievable spatial resolution and artery-to-background contrast due to the requirement of short acquisition at the optimal post-injection time. Also, the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis has not been completely cleared particularly in patients with renal failure although the risk can be significantly reduced by carefully selecting the type and dose of contrast agents (4,5).

Non-contrast-enhanced (NCE) MRA is free from the aforementioned limitations and has been an active MR research area in the past decade (6). The main technical goal of NCE MRA is to achieve high contrast between arteries and surrounding tissues and veins that is comparable or superior to CE methods. In addition to different relaxation rates, the relatively fast movement of arterial blood has been a promising source of its contrast against background materials. Flow-dependent NCE MRA methods include phase-contrast (PC) imaging(7), time-of-flight imaging (8,9), arterial spin labeling (ASL) (10,11), subtractive imaging based on flow-induced intra-voxel dephasing effects (12,13), and other variants (14–16).

For NCE renal MRA, a non-subtractive version of ASL, hereafter termed slab-selective (SS) inversion recovery (IR) imaging, has become popular (17–19). The SS-IR pulse sequence consists of an SS inversion pulse that excites the imaging volume as well as inferior veins, a subsequent delay time, and a 3DFT balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) readout (20,21). During the inversion delay time, fresh upstream arterial blood above the inversion volume is delivered to renal arteries while the inverted tissues and venous blood recover partially. Recent limited clinical studies have demonstrated that the diagnostic performance of this method in renal arteries is comparable to the standard CE approach (22,23).

The fundamental drawback of SS-IR imaging is that only upstream arterial blood outside the inversion volume can contribute to the final angiographic contrast. The SS inversion causes loss of arterial blood in the portion of abdominal aorta that is inside the inversion volume at the time of the inversion. Therefore, the tagging efficiency of arterial blood is sub-optimal. In practice, an inversion delay time of 1.0–1.4 s is commonly used for upstream arterial blood to be sufficiently delivered to distal renal arteries. However, these delay times are larger than the optimal value for suppressing kidney tissues and veins, which is approximately 700 ms at 1.5 T assuming a sufficiently long respiratory cycle for near-complete recovery of magnetization (see Fig. 1b in Ref. (24)). Another consequence of the inefficient arterial tagging is limited superior-inferior (S/I) coverage. It would require an impractically long inversion delay time for upstream arterial blood to reach the inferior abdominal aorta and iliac arteries. Recently, Atanasova et al. developed a large FOV abdominal MRA method where all spins except ones in the abdominal aorta were inverted by global inversion immediately followed by slice-selective re-inversion of the abdominal aorta (24). Abdominopelvic arteries over a large S/I FOV could be visualized, but at the expense of increased background signal at the location of the re-inversion pulse.

We propose a new NCE MRA method that overcomes the aforementioned limitations by employing an inversion preparation based on velocity selectivity instead of spatial selectivity. Velocity-selective (VS) inversion, when the direction of velocity selectivity is set to the S/I direction, can invert stationary tissues and venous blood only while preserving arterial blood in the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries. This relaxes the requirement for a long inversion delay time and allows imaging of arteries over a large S/I FOV. We describe the principle and design of a VS excitation pulse and demonstrate its use for NCE renal and abdominal MRA with a comparison to SS-IR MRA.

Theory

An excitation pulse sequence with a desired spatial-and velocity-selective profile can be designed using the excitation k-space formalism under the small tip approximation (25,26). An excited transverse magnetization at position r with velocity v and off-resonance f can be represented by a Fourier transform of the RF B1 field deposited in kr-kv-kf space, where kr, kv and kf are reciprocal Fourier variables of r, v and f, respectively.

| (1) |

where γ, M0 and T are the gyromagnetic ratio, magnetization at equilibrium and pulse duration, respectively. This is an extension of the conventional spatial-selective excitation by incorporating additional phase accrued by spin’s velocity and off-resonance. The nominal velocity profile obtained by Eq. (1) can be shifted by v0 along the velocity axis by modulating the phase of the B1 field. That is, for a shifted velocity profile ,

| (2) |

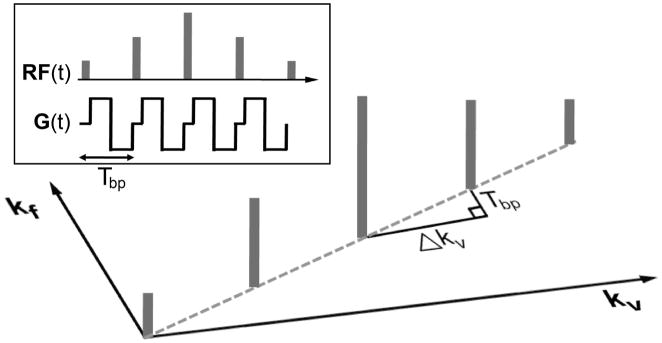

Velocity-selective and non-spatial-selective excitation can be achieved by playing hard RF sub-pulses between a series of bipolar gradients as illustrated in Fig. 1. Each bipolar gradient Gbp (t) with a time duration of Tbp changes kv by , changes kf by Tbp, but does not change kr due to the zero area of Gbp (t). In this way, the B1 field is deposited only when kr = 0, which ensures no spatial selectivity, with a desired shape of the B1 envelope that determines an excitation profile in the v - f plane. For large flip angles, the Fourier relation between the envelope of RF sub-pulses and the excitation profile would be less accurate. In this case, the RF envelope should be designed by the Shinnar-Le Roux (SLR) transform which converts the RF design into a low-pass filter design problem (27). It should be noted that, due to the discrete deposition of the B1 field, aliased excitation will occur at increments of away from the desired excitation along the velocity axis, where is termed as velocity FOV.

Figure 1.

Illustration of velocity-selective and non-spatial-selective excitation under excitation k-space formalism. With kv and kf defined as reciprocal Fourier variables of velocity v and off-resonance f, respectively, RF sub-pulses played between a series of bipolar gradients deposit B1 field on kv-kf space in a discrete fashion. Each bipolar gradient yields an increment of kv by and an increment of kf by Tbp (=time duration of the bipolar gradient). The discrete B1 deposit in the k-space causes excitation aliasing with a velocity FOV defined as the inverse of Δkv. The ratio between the kf and kv increments (Tbp/Δkv) determines the sensitivity to off-resonance which causes velocity profile shifting.

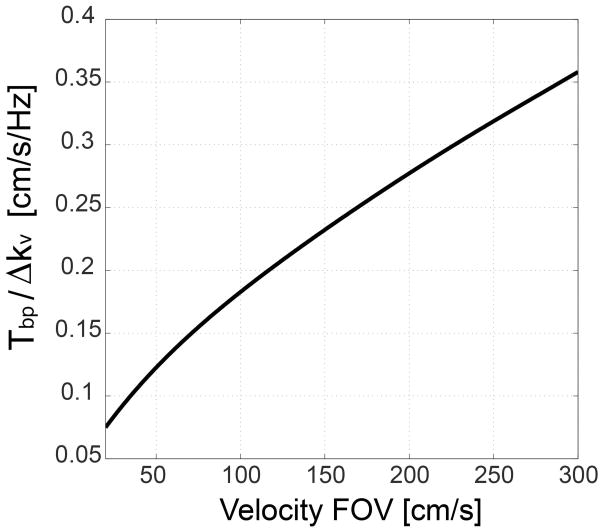

The effect of off-resonance can be explained by the excitation k-space trajectory tilted by the ratio of Tbp/Δkv with respect to the kv axis (dotted line in Fig. 1). Therefore, the excitation profile in the reciprocal v - f space is also tilted by the same ratio, which manifests as velocity profile shifting in proportion to off-resonance. The ratio Tbp /Δkv determines the amount of the profile shifting caused by unit off-resonance, and is simulated as a function of the velocity FOV in Fig. 2. The ratio monotonically increases as the velocity FOV increases, suggesting that a small velocity FOV is preferred to mitigate the off-resonance effect. The quadratic relationship between the ratio and the velocity FOV can be shown analytically as well. Δkv is proportional to the first moment of gradient and thus proportional to . Therefore, the ratio Tbp /Δkv is proportional to , and the velocity is proportional to .

Figure 2.

Off-resonance sensitivity of VS excitation. The ratio between kf and kv increments created by a bipolar gradient represents the velocity profile shifting by unit off-resonance, and is simulated as a function of the velocity FOV. The ratio monotonically increases with the velocity FOV, which suggests preference for a small velocity FOV. Maximum gradient amplitude and slew rate of 40 mT/m and 150 T/m/s were used to design a bipolar gradient for a given velocity FOV.

Materials and Methods

VS inversion pulse

A VS inversion pulse sequence involves several design parameters to be adjusted. Ideally, the velocity pass-band should have the largest possible upper bound, the smallest possible lower bound, and the narrowest possible transition-band to include various types of arterial flow. The achievable upper bound is limited by the preference to a small velocity FOV for reducing off-resonance-induced profile shifting, and the transition sharpness is traded off by a long pulse duration (or large number of RF sub-pulses). The stop-bandwidth should be minimized to increase the upper bound of the pass-band for a given velocity FOV. In designing a VS pulse, therefore, we sought the smallest possible velocity FOV and the largest possible number of RF sub-pulses that allow most of arterial blood and venous blood to be included in the pass-band and inversion-band, while limiting the pulse duration to less than 20 ms.

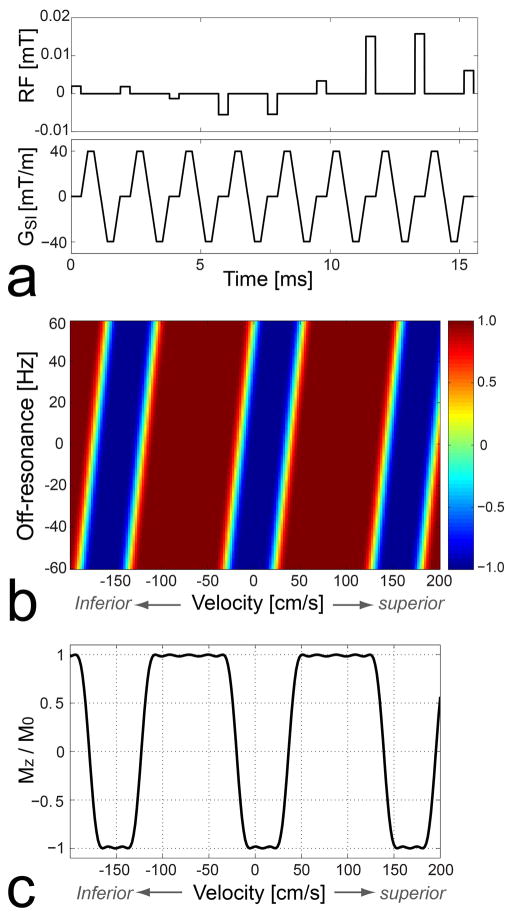

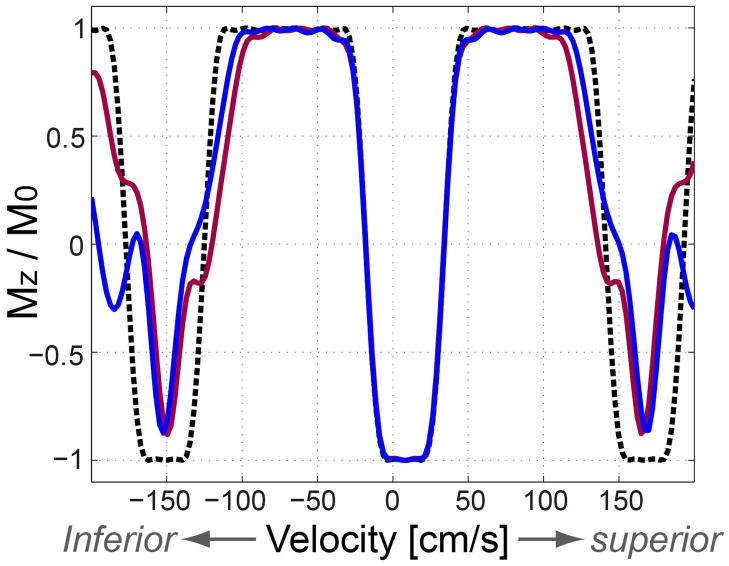

Figure 3 shows the VS inversion pulse sequence used in this study (a), Bloch simulation of the resultant longitudinal magnetization over v-f plane (b) and for water on resonance (i.e., f= 0) (c), respectively. In Figs. 3b and 3c, a positive velocity indicates flow moving superiorly (i.e., the direction of venous flow). The design parameters included velocity FOV = 160 cm/s, velocity inversion bandwidth = 60 cm/s (full-width-half-maximum), and the number of RF sub-pulses = 9. A bipolar gradient waveform was designed to generate Δkv of 1/160 s/cm (the inverse of the velocity FOV) using a maximum gradient amplitude of 40 mT/m and a maximum gradient slew rate of 150 T/m/s, and was 1.5 ms long. The velocity profile shifting by unit off-resonance (i.e., the ratio Tbp /Δkv ) was 0.24 cm/s/Hz. A minimum-phase filter was used for the SLR transform in designing the envelope of RF sub-pulses to reduce the pulse duration without compromising inversion performance. The total pulse duration was 15.7 ms. The nominal velocity profile, initially centered at 0 cm/s, was shifted by 8 cm/s in the superior direction using the RF phase modulation (Eq. 2).

Figure 3.

Velocity-selective inversion pulse sequence (a), Bloch simulation of the resultant longitudinal magnetization over the v-f plane (b) and for water on resonance (i.e., f= 0) (c). The design parameters included velocity FOV = 160 cm/s, velocity inversion bandwidth = 60 cm/s, and a minimum phase filter design for the SLR transform. On resonance, the VS pulse inverts spins with a velocity range of [−10, +25] (stationary tissues and venous blood) while barely affecting spins with a velocity range of [−110, −30] cm/s (arterial blood) where a positive value corresponds to a superior direction of velocity. Velocity profile shifting per unit off-resonance is 0.24 cm/s/Hz.

We define the effective velocity pass-band and inversion-band for a range of off-resonance as the widest velocity ranges that yield Mz larger than 0.9M0 and smaller than −0.9M0, respectively, regardless of velocity profile shifting caused by the given range of off-resonance. On resonance, the effective pass-band of the VS pulse is [−110, −30] cm/s, which includes arterial blood at a peak systolic phase, and the inversion-band is [−10, +25] cm/s, which includes stationary tissues and venous blood. The effective pass-band and inversion-band are narrowed in the presence of field inhomogeneity. For example, an off-resonance range of [−50, +50] Hz reduces the two bands to [−98, −42] cm/s and [+2,+13] cm/s, respectively.

Pulse sequence

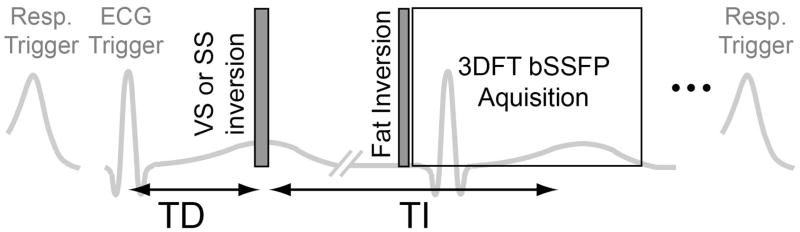

The pulse sequence for the proposed VS-IR MRA was triggered by respiratory bellows and ECG signals sequentially. After a respiratory trigger, the sequence consisted of a VS inversion pulse played after a cardiac trigger delay (TD), an inversion delay time (TI), a spectral-selective fat inversion pulse, and a bSSFP 3DFT readout with a linear view order (Fig. 4). Acquisition of ky phase encoding lines per kz encode was segmented over two respiratory cycles, which resulted in a total scan time of 2×(number of kz encodes)×(a period of respiratory cycle). The SS-IR method was also implemented for comparison by replacing the VS inversion pulse with an SS inversion pulse in the same sequence description. The cardiac trigger delay times for the VS and SS inversion pulses were determined for the optimal performance of each method, as described in the following subsection.

Figure 4.

Timing diagram of VS-IR (or SS-IR) NCE MRA sequence. The pulse sequence was triggered by bellows and ECG signals sequentially, and consisted of a VS (or SS) inversion pulse, an inversion delay time (TI), a spectral-selective fat inversion pulse, and a segmented bSSFP 3DFT readout. The VS pulse was played at the time of peak systolic flow whereas the SS pulse was played at the onset of systolic flow by adjusting a trigger delay (TD) with respect to the R wave, based on prior PC flow measurements.

Imaging protocol

In-vivo experiments were performed on a 1.5-T clinical whole-body MR system (Signa HDx; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). The body coil was used for RF excitation. An eight-channel cardiac-array coil was used for signal reception. Nine healthy subjects (age=34.2±3.8) were scanned after written consent forms approved by our institutional review board were obtained.

Per subject, 2D PC flow MRI was performed with an axial imaging orientation at one or multiple S/I positions. Through-plane flow in the abdominal aorta or iliac arteries was measured and displayed over cardiac phases to find a trigger delay for the maximum or onset of systolic flow. Imaging parameters were VENC = 150 cm/s, spatial resolution = 1.8×1.8 mm2, FOV = 260×260 mm2, slice thickness = 6 mm, flip angle = 25°, views per segment = 2, temporal resolution = 20.6 ms, and acquisition time = 70 heart beats.

NCE MRA scans were performed on subjects using two protocols that target (i) renal arteries over a small S/I FOV and (ii) abdominopelvic arteries over a large S/I FOV.

Renal MRA was performed using the proposed VS-IR and the traditional SS-IR methods on three subjects. Imaging parameters that were common to the two methods, included imaging orientation = axial, TI = 700 ms, flip angle = 70°, spatial resolution = 1.4×1.4×2.0 mm3, FOV = 280×200×100 mm3, TR = 4.6 ms, readout bandwidth = 125 kHz, number of phase encodes per acquisition block = 70, acquisition time per respiratory cycle = 322 ms. PC flow imaging of an axial slice was performed at isocenter (at approximately the level of the renal arteries). The VS inversion pulse was played at the time of peak systolic flow to maximize the velocity difference between arterial blood and background tissues. The SS inversion pulse was played at the time of the onset of systolic flow to maximize arterial inflow. In SS-IR imaging, the SS inversion volume was larger than the imaging volume by 20 mm in the superior direction and by 140 mm in the inferior direction.

Abdominal MRA with a large S/I FOV was performed using the VS-IR method on six subjects. Imaging parameters included imaging orientation = coronal, TI = 700 ms, flip angle = 70°, spatial resolution = 1.4×1.4×2.0 mm3, FOV = 340×300×120 mm3, TR = 4.7 ms, readout bandwidth = 125 kHz, two-fold acceleration using Iterative Self-consistent Parallel imaging Reconstruction (SPIRiT) with 32 self-calibration lines (28), number of phase encodes per acquisition block = 61, acquisition time per respiratory cycle = 287 ms. SS-IR imaging was performed for comparison on one of the six subjects using the same imaging parameters except with both TI = 700 ms and 1200 ms. PC flow imaging was performed to measure arterial velocities at three axial slices: at isocenter (i.e., approximately at the origin of iliac arteries) and displaced from the isocenter by 120 mm superiorly and inferiorly. The VS inversion pulse was played at the time of peak systolic flow measured at the isocenter whereas the SS inversion pulse was played at the time of the onset of systolic flow measured at the 120 mm-superior position. Using the PC velocity measurements, the efficacy of the VS profile was retrospectively investigated by calculating the percentage of measured arterial blood that is included in the velocity pass-band at the time of the VS preparation. Using the same PC data, the tolerance of sub-optimal TDs was also investigated by finding TDs that ensure at least 90 % of the measured arterial blood to be included in the velocity pass-band.

Results

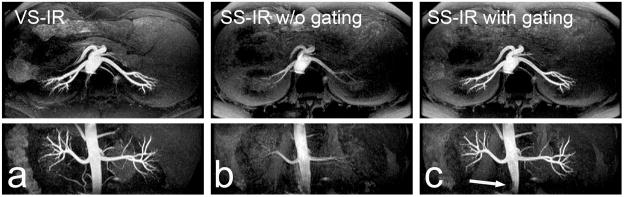

Figure 5 shows renal MR angiograms using VS-IR imaging (a) and SS-IR imaging (b and c) with TI = 700 ms (protocol (i)). Maximum intensity projection (MIP) images along the axial and coronal directions are shown at the top and bottom rows, respectively. The MIP images from VS-IR imaging show excellent visualization of renal arteries and suppression of background signals. The MIP images from SS-IR imaging show poor depiction of renal arteries without ECG gating due to insufficient arterial inflow. With the optimized ECG gating (i.e., SS inversion pulse played at the onset of systolic flow), artery visualization is significantly improved except at a small inferior segment of the abdominal aorta (arrow in Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

Axial (top) and reformatted coronal (bottom) maximum-intensity-projection (MIP) images of NCE renal MRA from protocol (i). MIP images from VS-IR imaging show excellent contrast between arteries and background tissues (a). MIP images from SS-IR imaging without ECG gating show poor depiction of arteries due to insufficient arterial inflow (b). Images from SS-IR with the optimized ECG gating show significantly improved artery visualization except at an inferior segment of the abdominal aorta (arrow in c).

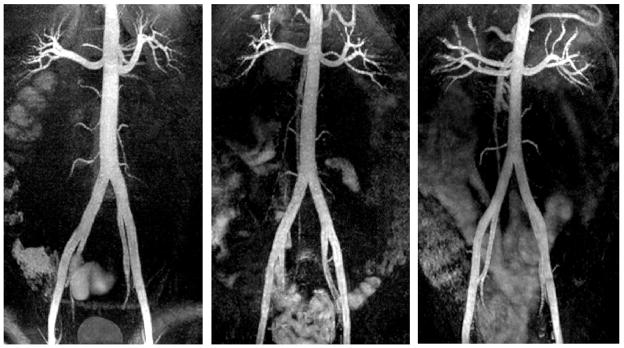

Figure 6 contains representative coronal MIP images of abdominal VS-IR MRA in three subjects. The abdominal aorta, renal arteries and iliac arteries are well visualized, which demonstrates successful VS separation of arterial blood from background tissues over the entire S/I FOV. With a TI of 700 ms, background signal is well suppressed except in the intestine that contains short T1 contents (29). Slight spatially-varying shading is seen in the arteries presumably due to receiver coil sensitivity variation, B1 inhomogeneity, and a non-ideal excitation profile. The trigger delay times for the VS inversion ranged 174 ms to 215 ms in six subjects (mean = 204.8 ms, standard deviation = 17.2 ms).

Figure 6.

Results of abdominal VS-IR MRA from protocol (ii). Representative coronal MIP images from three subjects show excellent visualization of the abdominal aorta, renal arteries, and iliac arteries throughout the entire S/I FOV. Background signals are well suppressed except in the intestine that contains short T1 contents. Excellent arterial contrast and overall background suppression were achieved using a relatively short TI of 700 ms due to well-preserved arterial blood in the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries during the VS preparation.

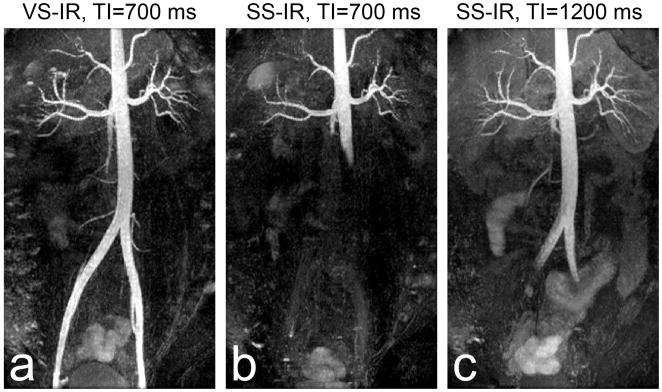

Figure 7 shows a comparison between abdominal VS-IR and SS-IR MRA in the same subject. While VS-IR MRA with TI = 700 ms yields excellent artery visualization (a), SS-IR MRA with the same TI is only able to visualize the abdominal aorta up to approximately 100 mm from the top of the FOV due to limited arterial inflow (b). The extent of the aorta is significantly increased with TI = 1200 ms, but only up to the beginning of iliac arteries (c). Furthermore, due to the longer TI, background signal is increased compared to the case of TI = 700 ms. Note that the optimized ECG gating was used for the abdominal SS-IR scans.

Figure 7.

Comparison of abdominal VS-IR versus SS-IR MRA in a subject for protocol (ii). VS-IR MRA with a TI of 700 ms results in excellent artery visualization throughout the entire FOV (a), similar to the results shown in Fig. 6. SS-IR MRA with the same TI results in limited coverage of the abdominal aorta due to insufficient arterial inflow (b). SS-IR with an increased TI of 1200 ms increases the angiographic spatial coverage but only up to the beginning of the iliac arteries and at a cost of slightly increased background signal (c).

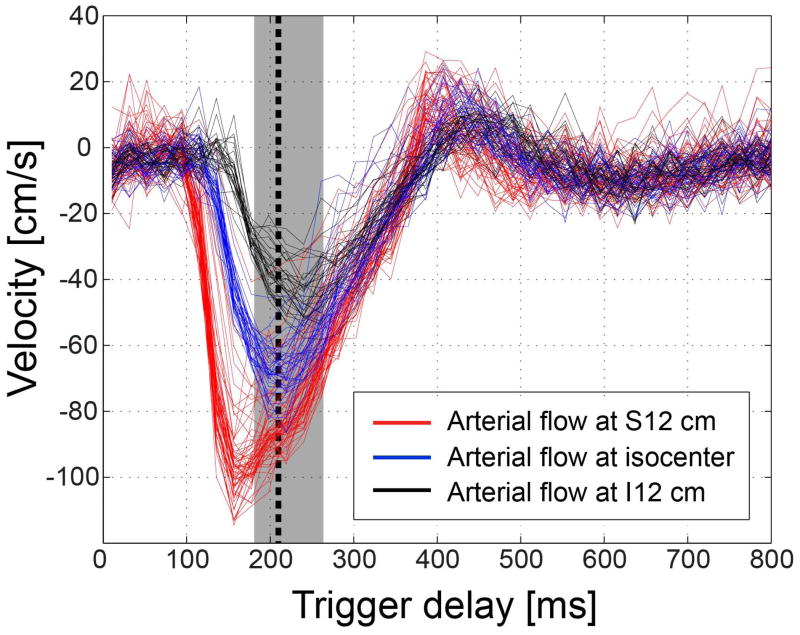

Figure 8 shows arterial blood velocities at three S/I locations in a subject for abdominal MRA. All voxel values across the entire lumen of the abdominal aorta or iliac arteries are displayed. In this subject, the trigger delay time for VS inversion was 215 ms (peak systolic flow at the isocenter). Downstream arterial blood exhibits lower peak velocities and reaches the peak flow later in time than upstream arterial blood. However, most of arterial velocities at all three locations fall within the on-resonance velocity pass-band (30 – 110 cm/s in the inferior direction) at the trigger delay of 215 ms. The percentage of voxels that are included in the on-resonance pass-band ranges 99.4% to 100% across six subjects (mean=99.3 %). Assuming an off-resonance range of [−50,+50] Hz and the corresponding effective pass-band of [−98, −42] cm/s, this ratio ranges 88.0 % to 100 % (mean=93.0 %). The range of trigger delays that ensure at least 90 % of arterial blood to be included in the on-resonance pass-band is 88.5±12.7-ms long across six subjects.

Figure 8.

Velocity of arterial flow at a 120 mm-superior position (red), at isocenter (blue), and at a 120 mm-inferior position (black) in a subject for abdominal MRA. The three S/I positions are at the abdominal aorta (approximately neighboring the renal arteries), the origin of iliac arteries, and the middle of iliac arteries, respectively. All pixel values across the entire vessel lumen of the abdominal aorta or iliac arteries are shown. While the peak value and the time of peak systolic flow vary across S/I positions, most of measured velocities fall within the effective VS pass-bands for on-resonance ([−110, −30] cm/s) at the time of VS preparation (black dotted line, TD=215 ms). The TDs that ensure 90 % of arterial blood to be in the velocity pass-band ranges 185 ms to 268 ms in this subject (grey region).

Discussion

We have presented a new NCE renal and abdominal MRA using VS inversion preparation, and have demonstrated its feasibility in healthy volunteers. The proposed method shares the benefit of the conventional SS-IR method by producing high-contrast angiograms from a single acquisition without subtraction. Unlike the SS inversion that is sensitive to upstream arterial blood only, the VS inversion preserves arterial blood in the imaging volume during the preparation, and thus enables artery visualization over a large FOV. For this reason, although the proposed method was tested for both renal and abdominal MRA, its advantage over the SS-IR method will be more significant in abdominal MRAwith a large S/I FOV.

Another benefit of the VS-IR method is the use of an inversion delay time that is chosen primarily based on background suppression rather than arterial inflow. The TI of 700 ms was chosen after preliminary in-vivo experiments at several TI values based on the highest contrast ratio between the main renal artery and the kidney parenchyma. However, the suppression level varies depending on specific relaxation times of different tissues (medulla, cortex, vein and liver), and the respiratory rate which determines the level of magnetization recovery until the next inversion preparation. Acquisition view order is another factor that affects the background suppression. A centric view order would require a shorter TI for the same suppression performance as with a linear view order due to reduced pre-saturation before the acquisition of the k-space origin.

A large angiographic abdominopelvic coverage was also achieved in a recent study by Atanasova et al. (24). In their approach, a global inversion followed by a sagittally oriented SS inversion of the abdominal aorta was used to invert all tissues but arterial blood in the aorta so that arterial inflow can start from the origin of the iliac arteries. While promising results were obtained in a cohort of patients, a bright background sagittal band at the location of the SS re-inversion remains a minor issue. Another flow-dependent method employed flow-sensitive dephasing (FSD) preparation to obtain a dark-artery image, which was subtracted from a reference image to generate an artery-only image (14,16). VS saturation was approximately achieved with a sufficiently large bipolar gradient due to dephasing of magnetizations with a range of velocities in a voxel. While this technique was successfully applied to the lower extremities, it requires two acquisitions and would be less effective in abdominal applications due to the orthogonal orientation of the renal arteries with respect to the abdominal aorta, which makes VS inversion more desirable.

The main issue of VS excitation is the velocity profile shifting in proportion to off-resonance. The VS inversion pulse used in this study has the off-resonance sensitivity of 0.24 cm/s/Hz, which reduces the effective velocity pass-band from [−110, −30] cm/s on resonance to, for example, [−98, −42] cm/s in the presence of ±50 Hz off-resonance. Nevertheless, since the on-resonance bandwidths were purposely set large to consider the profile shifting, the narrowed bands were still able to separate arterial blood from background materials. According to the analysis of PC velocity measurements, the portion of arterial blood that is included in the effective pass-band was reduced only marginally from 99.3 % (on-resonance) to 93.0 % (±50 Hz) on average over six subjects.

A limitation of this study is the validation of the VS-IR MRA in healthy volunteers only. In various cases of vascular diseases, the performance of the technique may be degraded to a varying degree depending on the speed and direction of flow in the diseased vasculature. For instance, arterial blood magnetization in turbulent or vortex flow caused by abdominal stenosis or aneurysm may be undesirably excited by the VS inversion. As those magnetizations are unlikely to move in a coherent fashion during the inversion delay, the resultant signal loss is not expected to be significantly noticeable but present in a diffuse and benign form. Abdominal arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a more challenging situation due to the presence of conglomerate tortuous vasculature. While a certain extent of the AVM could be visualized by utilizing time-of-flight of feeding arterial blood, visualization of the draining vessel is expected to be challenging. In all of the aforementioned cases, a larger inversion delay than the one used in this study is probably favored to increase the time-of-flight effects at a cost of increased background signal.

High-order motion of arterial blood is another potential source of sub-optimal performance of the VS excitation that was designed under the assumption of a temporally constant velocity. Figure 9 shows Bloch simulation of the VS inversion pulse in the presence of a linear time-variation of velocity. For each nominal velocity, a 20 % linear increase (purple solid line) and a 20 % linear decrease (blue solid line) of velocity are assumed for the simulation of the VS inversion. The distortion of the velocity profile is marginal in the velocity range of interest (−100 cm/s to +20 cm/s) while the distortion becomes more severe as the nominal velocity increases. Although the actual pattern of velocity variation may be more complex than simply being linear, depending on cardiac trigger delays and vascular conditions of subjects, potential deviation from the linear approximation should not be significant due to the fairly short pulse duration (~16 ms).

Figure 9.

Effect of a linear time-variation of velocity on VS inversion performance. Per nominal velocity, no variation (black dotted line), 20 % linear increase (purple solid line), and 20 % linear decrease (blue solid line) in velocity are assumed during the 16 ms-long VS inversion. The two linear variations are assumed to have the nominal value at 80% of the pulse duration where most excitation occurs due to the RF envelope designed by the minimum phase filter. In the velocity range of interest ([−100, 20] cm/s), the distortion of the velocity excitation profile is marginal.

The proposed technique at the field strength of 3 T will benefit from increased signal-to-noise ratio of arterial blood, but face technical challenges mainly due to increased B0 inhomogeneity. The potential issues caused by larger B0 inhomogeneity include increased velocity profile shifting and SSFP banding artifact. Potential technical improvements for the applicability to 3 T include high-order shimming (30), wide-band SSFP imaging (31), and VS excitation pulse design optimized for increased B0 offsets, among others.

The SS-IR MRA sequence available in clinical scanners does not typically use cardiac gating. We found from the renal MRA study (protocol (i)) that visualization of arteries was significantly improved when SS inversion, especially for the shorter 700-ms TI, was synchronized at the beginning of systolic flow to maximize inflow of upstream blood (Fig. 5). Based on this finding, we performed SS-IR imaging with the optimized gating only for the subsequent abdominal MRA study (protocol (ii)). Most arterial flow in the abdominal aorta and renal arteries occurs during a relatively short systolic period (200 – 300 ms) in each R-R interval (32). Thus, it is important to have a full systolic period within an inversion delay time, which is not always the case with a TI of 700 ms. The optimized timing of SS inversion is critical particularly for abdominal MRA, which involves a large extent of vasculature to be traversed by inflowing arterial blood. While the angiographic spatial coverage of SS-IR imaging was shown to be small compared with VS-IR imaging in abdominal MRA, the extent of visible arteries would have been smaller without the optimized cardiac gating.

Conclusions

A new NCE renal and abdominal MRA method using VS-IR bSSFP imaging has been developed. Compared to conventional SS-IR imaging, VS-IR imaging allows for a larger S/I FOV and a more flexible choice of TI due to preservation of arterial blood during the inversion preparation. In-vivo tests in healthy volunteers have demonstrated high contrast renal and abdominal angiograms using a TI chosen for optimal background suppression. In particular, abdominal VS-IR MRA has a significantly larger angiographic spatial coverage compared with the SS-IR approach, covering renal arteries through iliac arteries over an S/I FOV of 340 mm.

Acknowledgments

Grant Sponsors:

National Institutes of Health (5R01 HL075803)

GE Healthcare

The authors thank Shreyas S. Vasanawala (M.D., Ph.D., Stanford University) and Michael V. McConnell (M.D., Stanford University) for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Prince MR. Gadolinium-enhanced MR aortography. Radiology. 1994;191(1):155–164. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilman AH, Riederer SJ, King BF, Debbins JP, Rossman PJ, Ehman RL. Fluoroscopically triggered contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography with elliptical centric view order: application to the renal arteries. Radiology. 1997;205(1):137–146. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.1.9314975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruehm SG, Hany TF, Pfammatter T, Schneider E, Ladd M, Debatin JF. Pelvic and lower extremity arterial imaging: diagnostic performance of three-dimensional contrast-enhanced MR angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(4):1127–1135. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1741127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo PH, Kanal E, Abu-Alfa AK, Cowper SE. Gadolinium-based MR contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Radiology. 2007;242(3):647–649. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2423061640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin DR, Krishnamoorthy SK, Kalb B, Salman KN, Sharma P, Carew JD, Martin PA, Chapman AB, Ray GL, Larsen CP, Pearson TC. Decreased incidence of NSF in patients on dialysis after changing gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI protocols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(2):440–446. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyazaki M, Lee VS. Nonenhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2008;248(1):20–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumoulin CL, Souza SP, Walker MF, Wagle W. Three-dimensional phase contrast angiography. Magn Reson Med. 1989;9(1):139–149. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910090117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masaryk TJ, Laub GA, Modic MT, Ross JS, Haacke EM. Carotid-CNS MR flow imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14(2):308–314. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laub GA. Time-of-flight method of MR angiography. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 1995;3(3):391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura DG, Macovski A, Pauly JM, Conolly SM. MR angiography by selective inversion recovery. Magn Reson Med. 1987;4(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910040214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelman RR, Siewert B, Adamis M, Gaa J, Laub G, Wielopolski P. Signal targeting with alternating radiofrequency (STAR) sequences: application to MR angiography. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31(2):233–238. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meuli RA, Wedeen VJ, Geller SC, Edelman RR, Frank LR, Brady TJ, Rosen BR. MR gated subtraction angiography: evaluation of lower extremities. Radiology. 1986;159(2):411–418. doi: 10.1148/radiology.159.2.3961174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki M, Sugiura S, Tateishi F, Wada H, Kassai Y, Abe H. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography using 3D ECG-synchronized half-Fourier fast spin echo. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12(5):776–783. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200011)12:5<776::aid-jmri17>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan Z, Sheehan J, Bi X, Liu X, Carr J, Li D. 3D noncontrast MR angiography of the distal lower extremities using flow-sensitive dephasing (FSD)-prepared balanced SSFP. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(6):1523–1532. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelman RR, Sheehan JJ, Dunkle E, Schindler N, Carr J, Koktzoglou I. Quiescent-interval single-shot unenhanced magnetic resonance angiography of peripheral vascular disease: Technical considerations and clinical feasibility. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):951–958. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priest AN, Graves MJ, Lomas DJ. Non-contrast-enhanced vascular magnetic resonance imaging using flow-dependent preparation with subtraction. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):628–637. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanazawa H, Miyazaki M. Time-spatial labeling inversion tag (t-SLIT) using a selective IR-tag on/off pulse in 2D and 3D half-Fourier FSE as arterial spin labeling. Proceeding of ISMRM, 10th Annual Meeting; Hawaii. 2002; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braendli M, Bongartz G. Combining two single-shot imaging techniques with slice-selective and non-slice-selective inversion recovery pulses: new strategy for native MR angiography based on the long T1 relaxation time and inflow properties of blood. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):725–728. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoh M, Buecker A, Stuber M, Günther RW, Spuentrup E. Free-breathing renal MR angiography with steady-state free-precession (SSFP) and slab-selective spin inversion: initial results. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1272–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oppelt A, Graumann R, Barfuss H, Fischer H, Hartl W, Shajor W. FISP- a new fast MRI sequence. Electromedica. 1986;54:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshpande VS, Shea SM, Laub G, Simonetti OP, Finn JP, Li D. 3D magnetization-prepared true-FISP: a new technique for imaging coronary arteries. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46(3):494–502. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glockner JF, Takahashi N, Kawashima A, Woodrum DA, Stanley DW, Takei N, Miyoshi M, Sun W. Non-contrast renal artery MRA using an inflow inversion recovery steady state free precession technique (Inhance): comparison with 3D contrast-enhanced MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(6):1411–1418. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoo MM, Deeab D, Gedroyc WM, Duncan N, Taube D, Dick EA. Renal artery stenosis: comparative assessment by unenhanced renal artery MRA versus contrast-enhanced MRA. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(7):1470–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atanasova IP, Kim D, Lim RP, Storey P, Kim S, Guo H, Lee VS. Noncontrast MR angiography for comprehensive assessment of abdominopelvic arteries using quadruple inversion-recovery preconditioning and 3D balanced steady-state free precession imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(6):1430–1439. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauly J, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. A k-space analysis of small-tip-angle excitation. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Rochefort L, Maître X, Bittoun J, Durand E. Velocity-selective RF pulses in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(1):171–176. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauly J, Le Roux P, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Parameter relations for the Shinnar-Le Roux selective excitation pulse design algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10(1):53–65. doi: 10.1109/42.75611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lustig M, Pauly JM. SPIRiT: Iterative self-consistent parallel imaging reconstruction from arbitrary k-space. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(2):457–471. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shonai T, Takahashi T, Ikeguchi H, Miyazaki M, Amano K, Yui M. Improved arterial visibility using short-tau inversion-recovery (STIR) fat suppression in non-contrast-enhanced time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP) renal MR angiography (MRA) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(6):1471–1477. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spielman DM, Adalsteinsson E, Lim KO. Quantitative assessment of improved homogeneity using higher-order shims for spectroscopic imaging of the brain. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40(3):376–382. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nayak KS, Lee HL, Hargreaves BA, Hu BS. Wideband SSFP: Alternating repetition time balanced steady state free precession with increased band spacing. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(5):931–938. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maier SE, Scheidegger MB, Liu K, Schneider E, Bollinger A, Boesiger P. Renal artery velocity mapping with MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5(6):669–676. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]