Abstract

Objective

To estimate trends in contraceptive use, especially long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) and condoms, among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women.

Methods

HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women in a multicenter longitudinal cohort were interviewed semiannually between 1998 and 2010 about sexual behaviors and contraceptive use. Trends in contraceptive use by women aged 18–45 years who were at risk for unintended pregnancy but not trying to conceive were analyzed using generalized estimating equations.

Results

Condoms were the dominant form of contraception for HIV-seropositive women and showed little change across time. Fewer than 15% of these women used no contraception. Between 1998 and 2010, LARC use rose among HIV-seronegative women from 4.8% (6/126) to 13.5% (19/141, p=0.02), but not significantly among seropositive women (0.9% (4/438) to 2.8% (6/213, p = 0.09). Use of highly effective contraceptives, including pills, patches, rings, injectable progestin, implants and intrauterine devices, ranged from 15.2% (53/348) in 1998 to 17.4% (37/213) in 2010 (p = 0.55). HIV-seronegative but not seropositive LARC users were less likely than nonusers to use condoms consistently (HR=0.51, 95% C.I. 0.32–0.81, p = 0.004 for seronegative women; HR = 1.09, 95% C.I. 0.96, 1.23 for seropositive women).

Conclusion

Although most HIV-seropositive women use contraception, they rely primarily on condoms and have not experienced the increase in LARC use seen among seronegative women. Strategies to improve simultaneous use of condoms and LARC are needed to minimize risk of unintended pregnancy as well as HIV transmission and acquisition of sexually transmitted infections.

Introduction

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are safe, effective, and have high satisfaction and continuation rates (1, 2). LARC methods include the copper T380A intrauterine device (IUD), the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, and the subdermal etonogestrel implant. In the United States, IUD use has been rising in recent years, from 1% of women using contraception in 1995, to 2% in 2002, and up to 5.5% (2.1 million women) in 2006–2008 (3). During 2006–2008, rates of LARC use reached 8.4% among U.S. Latina women and 10% among parous women of all ethnic backgrounds (4). In contrast, African-American women may be less likely than other U.S. women to use IUDs (5).

Effective contraception is often an unmet need among U.S. women who are seropositive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). As in the general U.S. population, pregnancies among HIV-seropositive women are frequently unintended (6, 7), and earlier studies showed that incorporation of effective contraception into management of HIV-seropositive women has been suboptimal (8–10). Condoms prevent transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infectious agents, but their use requires negotiation with partners, and contraceptive effectiveness in practice is suboptimal. Oral contraceptives require strict compliance, and they may have pharmacokinetic interactions with antiretroviral drugs. Hormonal contraceptives may alter the systemic or genital immune response or change the genital tract environment in ways that may affect HIV acquisition, transmission, or progression (11). However, a recent review by the World Health Organization (WHO) continues to support their use (12). Adherence to noncontraceptive medication regimens has been shown to be problematic for HIV-seropositive women (13). LARC methods provide an alternative, as these methods do not require adherence to daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly schedules and are highly effective.

Theoretical concerns regarding increased risk of pelvic infections, bleeding, alterations in antiretroviral pharmacokinetics, and viral shedding led the International Planned Parenthood Federation and WHO to advise against IUD use in HIV-seropositive women in a 1996 statement (14). However, a recent review indicated that while the safety data on hormonal and intrauterine contraception in HIV-seropositive women are limited, they are reassuring (15). A WHO technical statement found that all forms of contraception should be considered for HIV-seropositive women; it did note conflicting but concerning evidence that injectable progestins may increase HIV transmission among women and advised condom use for all women with or at risk for HIV (16). Studies from Africa have shown that for HIV-seropositive women, copper-containing IUDs have minimal to no impact on the incidence or severity of sexually transmitted infection rates and provide effective contraception (17, 18). A prospective cohort study found no significant increase in cervical shedding of HIV after IUD insertion (19). The same investigators found no significant difference in complication rates of copper IUD use between HIV-seropositive and negative women (17, 20). A more recent randomized trial comparing the copper T380A IUD and hormonal contraception not only validated this finding, but it also found that women using the IUD were less likely to have their CD4 lymphocyte count decline to <200 cells/μL than women on hormonal contraception (18). However, one potential concern is that women using highly effective contraception may be less likely to use condoms, perhaps because effective contraception reduces the perceived need to use condoms to prevent pregnancy (9).

Despite these reassuring safety data, a recent study of HIV-seropositive women from Russia found that, even with 94% eligibility for injectable contraception and 89% eligibility for IUDs, only 20% of study participants elected injectable contraception and 4% elected IUDs (21).Similar studies of LARC use among HIV-seropositive U.S. women have not been conducted since the increase in use of LARC. A 1999 U.S. study showed that LARC was used less often in HIV-seropositive women, with only 1.2% using IUDs, 0.9% using levonorgestrel implants and 7.2% using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) (8). Another U.S. study showed that IUD use was rare among HIV-seropositive women through 2005 (9). Whether HIV-seropositive women have participated in the recent trend toward LARC for women in need of contraception is unknown. The main objective of this analysis was to estimate recent trends in contraceptive use, with a focus on IUDs and contraceptive implants (LARC methods), in HIV-seropositive women and seronegative U.S. women. Our hypothesis was that LARC use among HIV-seropositive women has risen recently. A secondary objective was to explore correlations between LARC use and consistent male condom use.

Methods

This study was part of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), an ongoing multicenter observational cohort study of the health of HIV-seropositive women and HIV-seronegative comparison women considered to be at risk for HIV infection because of sexual and drug use behaviors. Detailed information describing the protocols, procedures, recruitment methods, and cohort characteristics has been described previously (22, 23). Enrollment occurred at 6 study consortia and enrolled 3,772 women over 2 discrete periods (23). These sites enrolled 2,628 women during the first enrollment period from October 1, 1994 to November 15, 1995 and an additional 1,144 women during the second enrollment period from October 1, 2001 to September 30, 2002. Written informed consent for the study was obtained after local human subjects committees approved the study protocols. This study is currently ongoing, and our analysis includes information obtained through 2010.

Women were questioned at six-month intervals by trained interviewers using a standardized instrument. Our analysis excluded visits 1–8 because of changes in the interview questionnaire after those visits, and because an analysis of contraceptive use early in WIHS has previously been published (8, 9). We included only women between the ages of 18 and 45 years of age at the time of WIHS enrollment. We excluded visits at which women were 46 years of age or older, were pregnant or attempting to conceive at the time of the visit, or reported no vaginal sex with a male partner since the prior visit. We also excluded women who reported a history of sterilization, hysterectomy, or oophorectomy prior to any visit, a diagnosis of menopause by self or clinician evaluation, or HIV seroconversion during study.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the study participants at the first eligible study visit. Since visits 1–8 (October 1994–September 1998) were excluded, for those participants enrolled before visit 9 (October 1998), we defined the first eligible study visit as their first visit that was included in our analysis (visit 9); for those enrolled after visit 9, we defined the first eligible study visit as their first WIHS enrollment visit. To describe trends in contraceptive use in HIV-positive women, we calculated frequencies and percentages of each contraceptive method use at every visit. To facilitate presentation, methods of contraception were divided into 6 mutually exclusive categories based on levels of effectiveness (24). We defined LARC methods as IUDs and implants. First, those using LARC with or without any other methods were placed in the LARC category. The other categories included DMPA, oral contraceptive pill, patch, or ring (PPR), male condoms, others (including but not limited to the female condom, diaphragm, foam, rhythm method, abstinence and emergency contraception), and none. We considered methods with failure rates <10/100 woman-years (LARC, DMPA, and PPR) to be highly effective.

To demonstrate overall trends in LARC use, we calculated frequencies and percentages of each LARC method, as well as IUDs and implants combined, at each visit for all women. We also calculated frequencies and percentages of male condom use at each visit for all women. Data on LARC use and male condom use were stratified by HIV status. The differences in percentages of LARC use and male condom use between 1998 and 2010 were tested for significance using the chi-square test. To account for possible changes in contraceptive use over time as HIV-seropositive women aged, we calculated age-standardized contraceptive rates at each visit using the age distribution from the first eligible visit. To assess for trends in contraceptive use, we used the chi-square test for linear trend as well as generalized estimating equation (GEE) models including visit as a covariate in the model. We also used GEE models to test for a correlation between LARC use and HIV status. Correlation between LARC and consistent male condom use was tested in the total analytic dataset, as well as stratified by HIV status. All GEE analyses controlled for aging of the population with time.

Results

The WIHS enrolled 3766 women. We excluded 352 women who were younger than 18 years or older than 45 years-old at the time of WIHS enrollment; 860 who reported hysterectomy, oophorectomy or sterilization at baseline; 315 who reported no male sex partners at all study visits; 70 who were menopausal by self and/or clinician report at most or all visits; and 10 who seroconverted from HIV-seronegative to seropositive during the study period. Of the remaining 2159 women, 573 of the original recruits requested disenrollment, were not active study participants, or died before visit 9. The 1586 remaining women (1075 HIV-seropositive and 511 seronegative) made up the study group, including 656 of the original recruits and 930 women enrolled in 2001–2002. Of these 1586 women, 479 remained in 2010. The other 1107 women were censored, including 285 at death, 59 at withdrawal from study, 22 at disenrollment, 408 after 45 years of age, and 333 when they met other exclusion criteria including menopause, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, sterilization, and lack of sexual activity with a male partner.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the remaining 1586 women at their first eligible study visit. Compared to HIV-seropositive women, seronegative women were younger and less likely to be insured, unemployed, and ever married.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics of All Study Participants at First Eligible Visit

| (N = 1586)* Total | HIV Seronegative (n=511) * | HIV Seropositive (n=1075)* | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean [SD]) | 32.6 | (6.7) | 30.5 | (7.4) | 33.6 | (6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| HIV RNA level (copies/ml) (median [min-max]) | 1000 | (48-1500000) | |||||

| CD4 count (cells/cmm) (median [min-max]) | 444 | (0–3838) | |||||

| Gravidity (median [min-max]) | 0 | (0–3) | 0 | (0–2) | 0 | (0–3) | 0.99 |

|

| |||||||

| Race or ethnicity | 0.74 | ||||||

| White (Hispanic) | 219 | 13.8 | 69 | 13.5 | 150 | 14 | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 193 | 12.2 | 66 | 12.9 | 127 | 11.8 | |

| African American (Hispanic) | 53 | 3.3 | 22 | 4.3 | 31 | 2.9 | |

| African American (non- Hispanic) | 864 | 54.5 | 273 | 53.5 | 591 | 55 | |

| Others (Hispanic) | 191 | 12.1 | 60 | 11.8 | 131 | 12.2 | |

| Others (non-Hispanic) | 65 | 4.1 | 20 | 3.9 | 45 | 4.2 | |

| Site | 0.01 | ||||||

| Brooklyn | 288 | 18.2 | 110 | 21.5 | 178 | 16.6 | |

| Bronx | 349 | 22 | 110 | 21.5 | 239 | 22.2 | |

| Washington D.C. | 230 | 14.5 | 67 | 13.1 | 163 | 15.2 | |

| Los Angeles | 330 | 20.8 | 102 | 20 | 228 | 21.2 | |

| San Francisco | 196 | 12.4 | 76 | 14.9 | 120 | 11.2 | |

| Chicago | 193 | 12.2 | 46 | 9 | 147 | 13.7 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married | 379 | 23.9 | 114 | 22.3 | 265 | 24.7 | |

| Living with partner | 204 | 12.9 | 46 | 9 | 158 | 14.7 | |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 292 | 18.4 | 81 | 15.9 | 211 | 19.7 | |

| Never married | 673 | 42.5 | 254 | 49.7 | 419 | 39 | |

| Other | 36 | 2.3 | 16 | 3.1 | 20 | 1.9 | |

| Education level | 0.43 | ||||||

| No college | 1035 | 65.7 | 320 | 63.5 | 715 | 66.8 | |

| Some college | 405 | 25.7 | 139 | 27.6 | 266 | 24.8 | |

| At least college graduate | 135 | 8.6 | 45 | 8.9 | 90 | 8.4 | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 990 | 62.5 | 286 | 56 | 704 | 65.5 | |

| Employed | 595 | 37.5 | 225 | 44 | 370 | 34.5 | |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Uninsured | 368 | 23.4 | 190 | 37.3 | 178 | 16.7 | |

| Insured | 1206 | 76.6 | 320 | 62.7 | 886 | 83.3 | |

| Income, annual | 0.53 | ||||||

| Less than $12000 | 787 | 50.1 | 252 | 49.7 | 535 | 50.3 | |

| $12000–24000 | 382 | 24.3 | 117 | 23.1 | 265 | 24.9 | |

| $24001 and higher | 402 | 25.6 | 138 | 27.2 | 264 | 24.8 | |

Data are n(%) unless otherwise specified.

SD, standard deviation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

For some categories, numbers may not sum to the column total because of missing data.

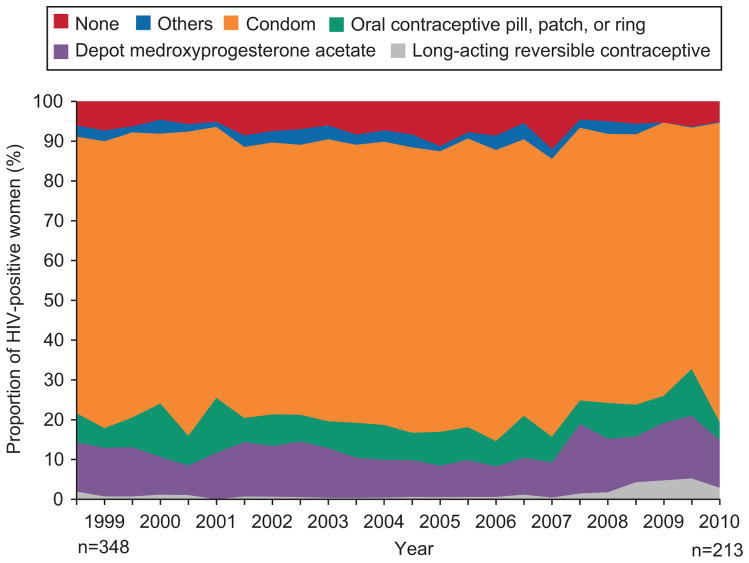

Fig. 1 presents trends in use of all forms of contraception across time by women with HIV, adjusted for age at enrollment. Only a minority of HIV-seropositive women at risk for unwanted pregnancy did not use contraception. This proportion ranged from 7.5% (26/348) in 1998 to 8.5% (18/213) in 2010, with a high of 12.1% (27/224) in 2009 (p for trend = 0.53). Male condoms were the dominant form of contraception used by HIV-seropositive women throughout observation. The proportion of women dependent on male condoms alone or with largely ineffective “other” forms of contraception remained stable across the duration of study, being 73.3% (255/348) in 1998 and 73.7% (157/213) in 2010 (P = 0.92). Aggregate use of highly effective contraception, including pills, patches, rings, DMPA, implants and IUDs, also did not change, accounting for 15.2% (53/348) of HIV-seropositive women at risk for pregnancy in 1998 and 17.4% (37/213) in 2010 (p=0.55).

Fig. 1.

Changes in contraception use over time in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive women. Contraceptive methods were divided into 6 mutually exclusive categories. Those using long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) and/or any other methods were placed in the “LARC” category; those using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and/or any other methods, excluding LARC, were placed in the “DMPA” category; those using any form of PPR and/or any other methods, excluding LARC and DMPA, were placed in the “oral contraceptive pill, patch, or ring (PPR)” category; those using male condoms and/or any other methods, excluding LARC, DMPA and PPR, were placed in the “condom” category; those using any other method not previously accounted for were placed in the “others” category; those using no contraception were placed in the None category.

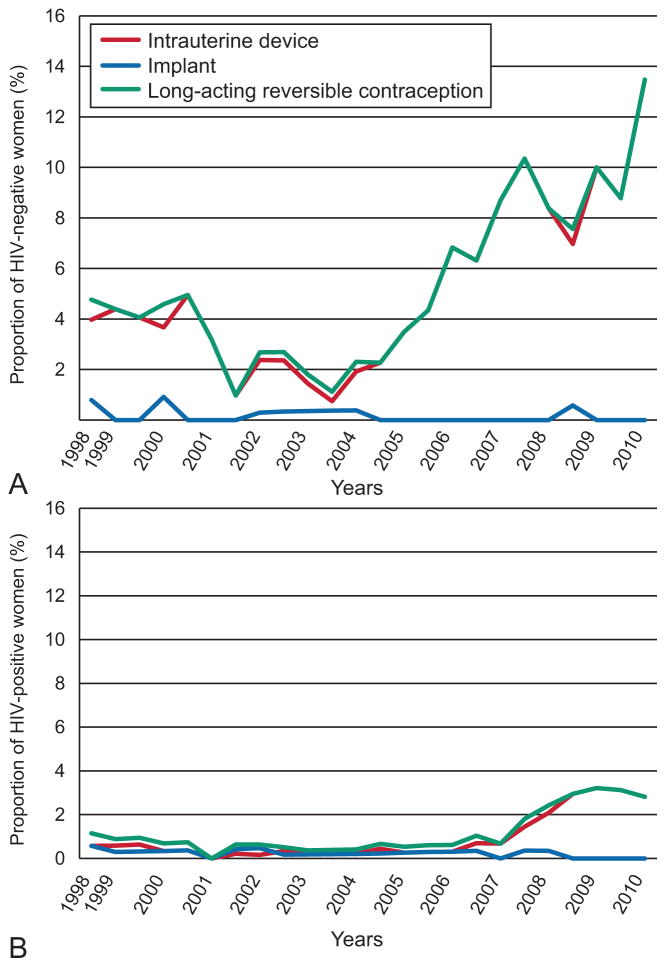

During most of the study period, rates of LARC use were low among both HIV-seropositive and seronegative women. LARC methods were used in 4/348 (1.1%) HIV-seropositive women and 6/126 (4.8%) of seronegative women in 1998. As shown in Fig. 2a, IUD use began to rise among HIV-seronegative women in about 2004–5. By 2010, 19 (13.5%) of 141 HIV-seronegative women at risk for pregnancy were using LARC, predominantly IUDs, with minimal use of implantable contraception. This increase in LARC use among HIV-seronegative women over time was significant (p = 0.02). Fig. 2b shows that IUD use among HIV-seropositive women appeared to lag use among HIV-seronegative women, increasing after 2007, but never reaching 4% of eligible women. By 2010, LARC use among HIV-seropositive women had risen to 6 (2.8%) of 213, although this increase did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.19 vs. 1998). As with HIV-seronegative women; use of implants has been negligible. GEE models also showed a significant trend in rising LARC use among HIV-seronegative women (P=0.001) but not seropositive women.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2a. Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use over time in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seronegative women. Fig. 2b. LARC1 use over time in HIV2 seropositive women. IUD, intrauterine device.

Our GEE analyses showed a significant association between LARC use and HIV status. HIV-seropositive women were less likely to use LARC than HIV-seronegative women (OR=0.21, 95% C.I. 0.12, 0.35, p < 0.001). We also found an association between LARC use and inconsistent male condom use, but only in HIV-seronegative women. Among these women, LARC users were less likely to use male condoms consistently (HR=0.51, 95% C.I. 0.32–0.81, p = 0.004). In contrast, among HIV-seropositive women there was no significant association between LARC and consistent male condom use (HR=1.09, 95% C.I. 0.96, 1.23, p = 0.19).

Discussion

Although most HIV-seropositive women in our study used contraception, most relied on male condoms alone rather than highly effective contraception. Rates of LARC use among HIV-seronegative women remained below 4% overall and did not increase over time, in contrast to a recent rise in LARC use among HIV-seronegative women. We have previously shown that most pregnancies among HIV-seropositive U.S. women are unintended (6, 7). Unintended pregnancies can disrupt lives already adversely affected by HIV, substance abuse, depression, and poverty. Given the benefits and minimal burden of LARC use strategies are needed to improve the uptake of LARC among women with HIV.

Use of LARC may reduce concurrent male condom use, perhaps by freeing women from the need to use male condoms to prevent pregnancy (9, 25). Indeed, LARC use was associated with less consistent male condom use among HIV-seronegative but not seropositive women in our study. This suggests that increasing LARC use among HIV-seropositive women might not increase their susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections or transmission of HIV to uninfected partners. Nonetheless, strategies including education aiming to increase LARC use among HIV-seropositive women also should include measures to maintain high levels of male condom use to avoid transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted pathogens.

Male condoms alone remained the dominant contraceptive throughout our study period. Condoms used alone are less effective than other forms of contraception, with a failure rate of approximately 15/100 woman-years (26). They require correct and consistent use, rely on a willing partner, and are subject to breakage. Effective forms of contraception other than LARC methods, including pills, patches, rings, and DMPA, were used by fewer than a third of women, and uptake did not increase across time in our cohort. These forms of contraception also require careful compliance and follow-up. Medication compliance may be a problem for some women, as studies of antiretroviral therapy have shown (13).

LARC methods offer effective contraception without need for partner cooperation or daily, weekly, or monthly, or quarterly medication compliance. Disadvantages may include high initial cost relative to alternatives, unpredictability of bleeding and the potential for penile abrasions from IUD strings or a partially expelled IUD, both of which may detract from acceptability among women concerned about transmitting HIV. Implants are considered safe in HIV-positive women, and an earlier WIHS study noted that hormonal contraceptives, including levonorgestrel subcutaneous implants, did not alter the effectiveness of HAART (27). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has advised that high risk for or actual HIV infection, and AIDS should not be considered contraindications to the use of progestin implants (28). Despite this, implant use has decreased in the HIV population, with no HIV-seropositive women in our study using the implant method at last follow-up in 2010. This may be partly due to the irregular bleeding that can occur with use of the implant, which in theory might raise concerns regarding HIV transmission. In addition, clinicians who treat women with HIV may not have access to providers trained in implant insertion. There is also concern regarding the effect of hormonal contraceptives on HIV disease acquisition and transmission. A recent study found that hormonal contraceptives may increase the risk of HIV-1 acquisition and transmission, though implantable hormonal methods and IUDs were excluded from this analysis (29). IUDs with their lower systemic levels of progestins may be preferable to implants for HIV-seropositive women seeking contraception.

Our study has several limitations. Despite the rising trend in LARC use, the absolute numbers of LARC users amongst both the HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative subgroups is low; this resulted in limited power to detect important correlates of LARC use, especially among HIV-seropositive women. Due to sample size constraints, we could only include two factors – HIV serostatus and male condom use in our multivariable analysis. We depended on self-reported contraception use, sexual exposure, and desire for pregnancy recorded at six-month intervals; self-report may be inaccurate or more dynamic than semiannual recording can capture; studies employing shorter reporting intervals or medical record review may be marginally more accurate. Our cohort did not include adolescents, and the uptake of LARC methods among HIV-seropositive adolescents remains to be studied. Our analysis also could not explore reasons why HIV-seropositive women were lagging behind their seronegative counterparts in terms of IUD use. Whether this is due to clinician discomfort or lack of training in promoting the IUD to their HIV-seropositive patients, to resistance to IUD use on the part of these women, to both, or to other factors remains to be investigated. Lack of IUD availability and clinician misconceptions about IUD safety have been correlated with lower rates of IUD provision (30). Concern about infection remains an obstacle to clinicians considering recommending IUDs (31), and may be especially so for clinicians caring for immunocompromised women. Further studies are needed to determine why so few HIV-seropositive women are adopting highly effective contraceptives, especially IUDs, as their contraceptive choice.

In conclusion, although most women with HIV use contraception, most rely on male condoms, and more effective contraceptive methods are underutilized. A recent technical statement from the World Health Organization called for expansion of the mix of contraceptive methods available to HIV-seropositive women and reaffirmed that there are no restrictions on the use of any hormonal contraceptive method for these women (16). LARC uptake should be encouraged, and strategies are needed to improve dual use of contraception methods, such as combined use of male condoms and IUDs, to minimize unintended pregnancy while protecting against sexually transmitted infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group for data collection: (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); and the Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange).

The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co- funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mengyang Sun, Division of Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Jeffrey F. Peipert, Division of Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Qiuhong Zhao, Division of Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Tracey E. Wilson, SUNY Downstate Medical Center School of Public Health, Brooklyn, NY

Kathleen M. Weber, Hektoen Institute of Medicine and the CORE Center at John H. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, IL.

Lorraine Sanchez-Keeland, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Gypsyamber D’Souza, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD.

Mary Young, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

D. Heather Watts, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD

Marla J. Keller, Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Deborah Cohan, University of California, San Francisco, CA

L. Stewart Massad, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

References

- 1.Blumenthal PD, Voedisch A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy: increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:121–37. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, Petrosky E, Madden T, Eisenberg D, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;29:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Hubacher D, Kost K, Finer LB. Characteristics of women in the United States who use long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1349–57. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c47c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehlendorf C, Foster DG, de Bocanegra HT, Brindis C, Bradsberry M, Darney P. Race, ethnicity and differences in contraception among low-income women: Methods received by Family PACT clients, California, 2001–2007. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:181–7. doi: 10.1363/4318111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsay MK, Grant J, Peterson HB, Willis S, Nelson P, Klein L. The impact of knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus serostatus on contraceptive choice and repeat pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:675–9. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00018-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massad LS, Springer G, Jacobson L, Watts H, Anastos K, Korn A, et al. Pregnancy rates and predictors of conception, miscarriage and abortion in US women with HIV. AIDS. 2004;18:281–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson TE, Massad LS, Riester KA, Barkan S, Richardson J, Young M, et al. Sexual, contraceptive, and drug use behaviors of women with HIV and those at high risk for infection: results from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS. 1999;13:591–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massad LS, Evans CT, Wilson TE, Golub ET, Sanchez-Keeland L, Minkoff H, et al. Contraceptive use among U.S. women with HIV. J Womens Health. 2007;16:657–66. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kline A, Strickler J, Kempf J. Factors associated with pregnancy and pregnancy resolution in HIV seropositive women. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1539–47. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hel Z, Stringer E, Mestecky J. Sex steroid hormones, hormonal contraception, and the immunobiology of human immunodeficiency Virus-1 infection. Endocrine Reviews. 2010;31:79–97. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The U. S Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(RR04):1–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, Anastos K, Ostrow DG, Witt MD, et al. Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1377–85. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Improving Access to Quality Care in Family Planning: Medical eligibility criteria for initiating and continuing use of contraceptive methods. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis KM, Nanda K, Kapp N. Safety of hormonal and intrauterine methods of contraception for women with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS. 2009;23 (Suppl 1):S55–67. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000363778.58203.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Hormonal contraception and HIV: Technical statement. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/Hormonal_contraception_and_HIV.pdfRetrieved February 21, 2012. [PubMed]

- 17.Morrison CS, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Sinei SK, Weiner DH, Kwok C, Kokonya D. Is the intrauterine device appropriate contraception for HIV-1-infected women? BJOG. 2001;108:784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stringer EM, Kaseba C, Levy J, Sinkala M, Goldenberg RL, Chi BH, et al. A randomized trial of the intrauterine contraceptive device vs hormonal contraception in women who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:144.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson BA, Morrison CS, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Sinei SK, Overbaugh J, Panteleeff DD, et al. Effect of intrauterine device use on cervical shedding of HIV-1 DNA. AIDS. 1999;13:2091–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910220-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinei SK, Morrison CS, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Allen M, Kokonya D. Complication of use of intrauterine devices among HIV-1-infected women. Lancet. 1998;351:1238–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteman MK, Kissin DM, Samarina A, Curtis KM, Akatova N, Marchbanks PA, et al. Determinants of contraceptive choice among women with HIV. AIDS. 2009;23 (Suppl 1):S47–54. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000363777.76129.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruitt SL, von Sternberg K, Velasquez MM, Mullen PD. Condom use among sterilized and nonsterilized women in county jail and residential treatment centers. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:386–93. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trussell J. Contraceptive Efficacy. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive Technology. 19. New York (NY): Ardent Media; 2007. pp. 747–826. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu Jaclyn H, Gange SJ, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Cejtin H, Bacon M, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and the effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:881–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Early Release. 4. 2010. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. Adapted from the World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, Celum C, Mugo N, Were E, et al. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyler CP, Whiteman MK, Zapata LB, Curtis KM, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA. Health care provider attitudes and practices related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:762–71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: a survey of obstetrician and gynecologists’ knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 2010;81:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]