Abstract

F1-ATPase is an ATP-driven rotary molecular motor that synthesizes ATP when rotated in reverse. To elucidate the mechanism of ATP synthesis, we imaged binding and release of fluorescently labelled ADP and ATP while rotating the motor in either direction by magnets. Here we report the binding and release rates for each of the three catalytic sites for 360° of the rotary angle. We show that the rates do not significantly depend on the rotary direction, indicating ATP synthesis by direct reversal of the hydrolysis-driven rotation. ADP and ATP are discriminated in angle-dependent binding, but not in release. Phosphate blocks ATP binding at angles where ADP binding is essential for ATP synthesis. In synthesis rotation, the affinity for ADP increases by >104, followed by a shift to high ATP affinity, and finally the affinity for ATP decreases by >104. All these angular changes are gradual, implicating tight coupling between the rotor angle and site affinities.

Reverse rotation of the F1-ATPase results in the synthesis, rather than hydrolysis of ATP. Adachi et al. show that the molecular mechanism of ATP synthesis is the reverse of hydrolysis-driven rotation of the motor, and that ADP and ATP are discriminated by angle-dependent binding.

Reverse rotation of the F1-ATPase results in the synthesis, rather than hydrolysis of ATP. Adachi et al. show that the molecular mechanism of ATP synthesis is the reverse of hydrolysis-driven rotation of the motor, and that ADP and ATP are discriminated by angle-dependent binding.

The F1-ATPase is the catalytic core of the FoF1-ATP synthase that synthesizes ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) using the proton-motive force across a membrane1,2,3,4,5,6. In isolation, F1 only hydrolyses ATP, hence the name F1-ATPase. Isolated F1 has been shown to be an ATP-driven rotary molecular motor7, as predicted8,9. The central γ subunit rotates against the surrounding cylinder made of α3β3 subunits alternately arranged10. These seven subunits (α3β3γ) suffice for ATP hydrolysis and rotation, and hereafter we call this subcomplex F1. Reverse rotation of the γ subunit forced by magnets leads to ATP synthesis11,12, that is, the reversal of the hydrolysis reaction in the three catalytic sites each hosted primarily by a β subunit10. In vivo, the other component Fo of the ATP synthase forces F1 to rotate in reverse using the energy of transmembrane proton flow, thus supplying ATP to animals, plants and aerobic bacteria.

Although the ATP-driven rotation of F1 has been characterized extensively in single-molecule observations7,13,14,15, little information is available for the angle-dependent events in the reverse rotation that leads to ATP synthesis. The reversal of the chemical reaction accomplished by forced γ rotation suggests a γ-dictator mechanism in which the chemical states of the three catalytic sites are determined by the γ angle. The γ angle, in turn, is controlled by the torque generated by binding and release of nucleotides in the three catalytic sites, and thus the three sites communicate with each other through γ rotation. The recent reports of rotation of an axle-less16 and γ-less17 F1 implicate direct communication between catalytic sites, but the efficiency is low and ATP synthesis without γ is unlikely. Thus, we expect nucleotide affinities of the three catalytic sites to be unique functions of the γ angle, independent of the rotation direction. Here, we test this prediction by manipulating the γ angle through a magnetic bead(s) attached to the protruding portion of γ and directly imaging nucleotide binding.

We used F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3, of which ATP-driven rotation is well documented2,6. It rotates in steps of 120° per ATP13, and the 120° step is further resolved into 80–90° and 40–30° substeps14,15, which we refer to here as 80° and 40°. In the basic reaction scheme15, ATP binding initiates rotation from one of the three ATP-waiting angles, at for instance 0°. The ATP that is bound at 0° is hydrolysed into ADP and Pi in a millisecond dwell at ~200°, and the ADP is released around 240°, after a third ATP is bound. The site occupancy, that is the average number of bound nucleotides, remains two except for the brief moment between ATP binding and ADP release. The timing of Pi release is yet unsettled15,18,19: either at ~200°, ~320° or somewhere in between. Little is known about the angular timings during the reverse rotation for ATP synthesis.

Here, we have resolved the angular dependences of the rates of binding and release of ADP and ATP using fluorescent nucleotide analogues and by artificially slowing down the rotation with magnets. We found the rates to be unique functions of the rotary angle, irrespective of the rotary direction, indicating ATP synthesis by direct reversal of the hydrolysis-driven rotation. Both binding and release rates change progressively with rotation, by >102. ADP and ATP are discriminated in binding, but not significantly in release. The difference accounts for how ATP is synthesized and how hydrolysis-driven rotation takes place. An unexpected finding was that ATP binding in synthesis rotation, which would lower the efficiency of ATP synthesis, is blocked by weakly bound Pi. Observations in the presence of unlabelled nucleotides indicate similar kinetics at the normal site occupancy exceeding two, and that the kinetics of unlabelled nucleotides are not essentially different from those of the fluorescent nucleotides though the latter are slower in both binding and release. Our results clarify how Boyer's binding change mechanism1,8 for ATP synthesis operates, as gradual and differential changes of ATP and ADP affinities with modulation by Pi.

Results

Binding events during forced rotation

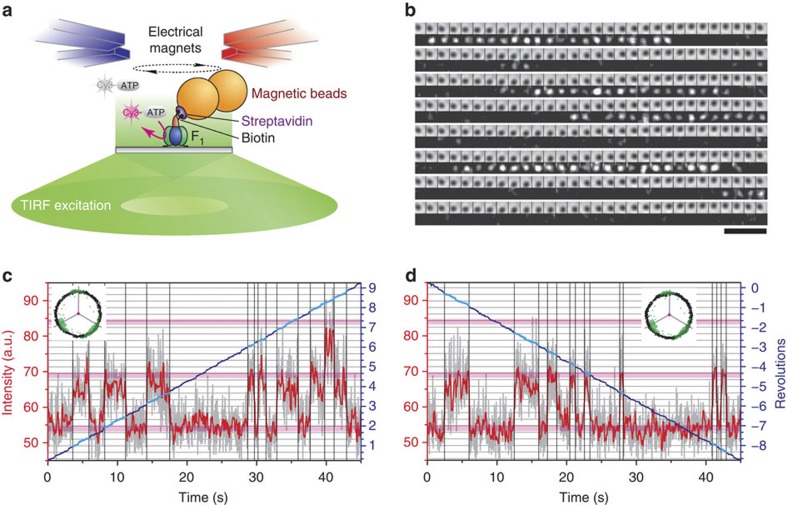

We observed binding and release of a fluorescent nucleotide analogue, Cy3-ATP or Cy3-ADP20,21, on single molecules of F1 fixed on a glass surface with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (Fig. 1a). Simultaneously, we rotated the magnetic bead(s) on γ with electromagnets while imaging the bead movement with bright-field microscopy. Cy3-nucleotide, when bound to F1, appeared as a brightly fluorescent stationary spot (Fig. 1b), while unbound and diffusing Cy3-nucleotide gave a dim, uniform background22. To resolve binding and release angles at the video rate of 30 frames s−1, we rotated the magnetic field in either direction at 0.2 Hz (0.05–0.5 Hz in some experiments). Preselected molecules (Methods) were observed for 5–60 min, typically ~20 min.

Figure 1. Simultaneous observation of manipulated rotation and Cy3-nucleotide binding.

(a) Experimental design (not to scale). Cy3-nucleotide was visualized by TIRF microscopy with conical excitation. (b) Sequential bright-field images, at 167-ms intervals, of magnetic beads (upper rows) and fluorescence images of single Cy3 molecules bound to F1 (lower rows) at 25 nM Cy3-ATP under a rotary magnetic field at 0.2 Hz in the hydrolysis direction. Images have been averaged over three frames (0.1 s) and, after dividing each pixel by 6×6, spatially averaged over 18×18 pixels (0.294×0.294 μm2). Scale bar, 5 μm. (c,d) Time courses of Cy3-ATP binding and bead rotation (0.2 Hz) in the hydrolysis (c) and synthesis (d) directions at 25 nM Cy3-ATP. Light-grey curves show fluorescence intensity in a spot of 8×8 pixels (0.784×0.784 μm2); red curves, after median filtering over eight frames (0.267 s). Pink horizontal lines, intensity levels for 0, 1 and 2 Cy3 molecules. Vertical black lines, binding or release. Blue curves, beads rotation, cyan parts with Cy3 bound. Horizontal grey lines, ATP-waiting angles separated by 120°. Insets, traces of bead centroid (green during unforced rotation in 60 nM ATP); grey radii, ATP-waiting angles.

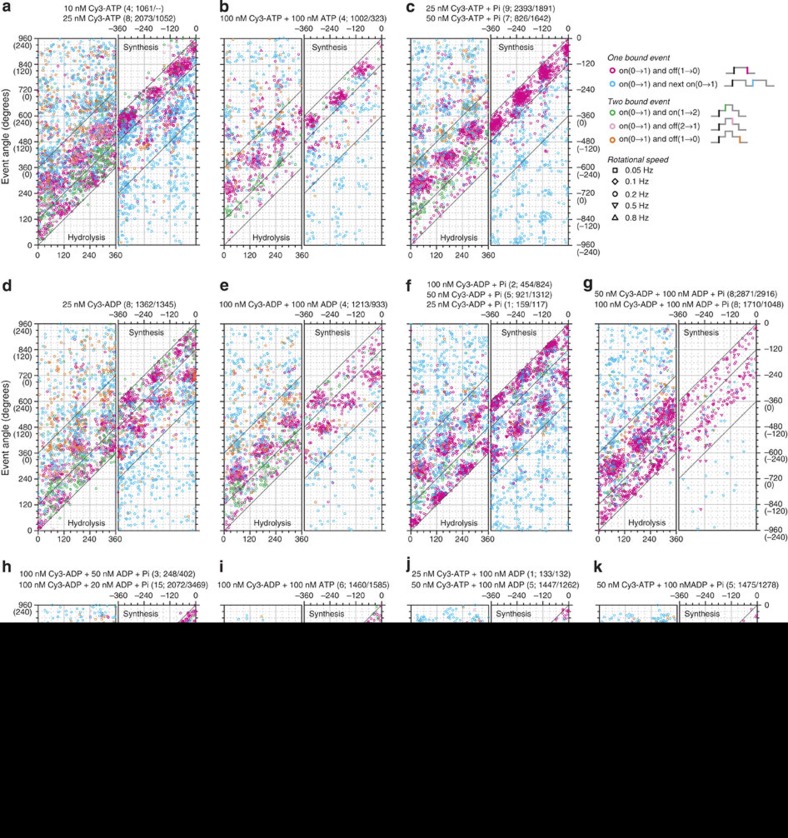

Cy3-nucleotide bound to F1 gave similar fluorescence intensities irrespective of its orientation, because the excitation was unpolarized in the sample plane15. The intensities of Cy3-ATP and Cy3-ADP were nearly indistinguishable. Thus, we could follow the changes in the occupancy number (the number of bound nucleotides) and identify binding events (Fig. 1c,d, and Supplementary Fig. S1). For binding events lasting three video frames (0.1 s) or longer, we determined the binding (θon) and release (θoff) angles from the bead image. Shorter events, possibly noise, were ignored. We took one of the three ATP-waiting angles, observed in 60-nM ATP before Cy3-nucleotide infusion, as θ=0°, and measured θ in the hydrolysis direction (θ decreases in synthesis). In Fig. 2, we plot angles of all binding events that began from an occupancy of zero, including second binding to occupancy two (see diagrams at top right); we never observed clear cases of an occupancy of three. The angles of the first on events (horizontal axis) as well as subsequent off or on angles (vertical axis) display basic 120° symmetry, as expected for the presence of three catalytic sites. The concentration of Cy3-nucleotide, [Cy3-nucleotide], or the rotary speed did not significantly affect the angle distributions.

Figure 2. Angular distributions of all binding events.

(a) Cy3-ATP. The conditions shown at the top. Numbers in parentheses are the number of molecules observed and the number of rotations in the hydrolysis/synthesis directions. Horizontal axis is the angle of the first on event (site occupancy number 0→1), and the vertical axis the angle of subsequent events defined on the right of c. Left panels are for hydrolysis rotations (the angle increases), and right panels synthesis (the angle decreases). Simple binding events (magenta) are reproduced in Fig. 3. (b) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ATP. (c) Cy3-ATP with 10 mM Pi. (d) Cy3-ADP. (e) Cy3-ADP+unlablled ADP. (f) Cy3-ADP with 10 mM Pi. (g,h) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi. (i) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ATP. (j) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP. (k) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi.

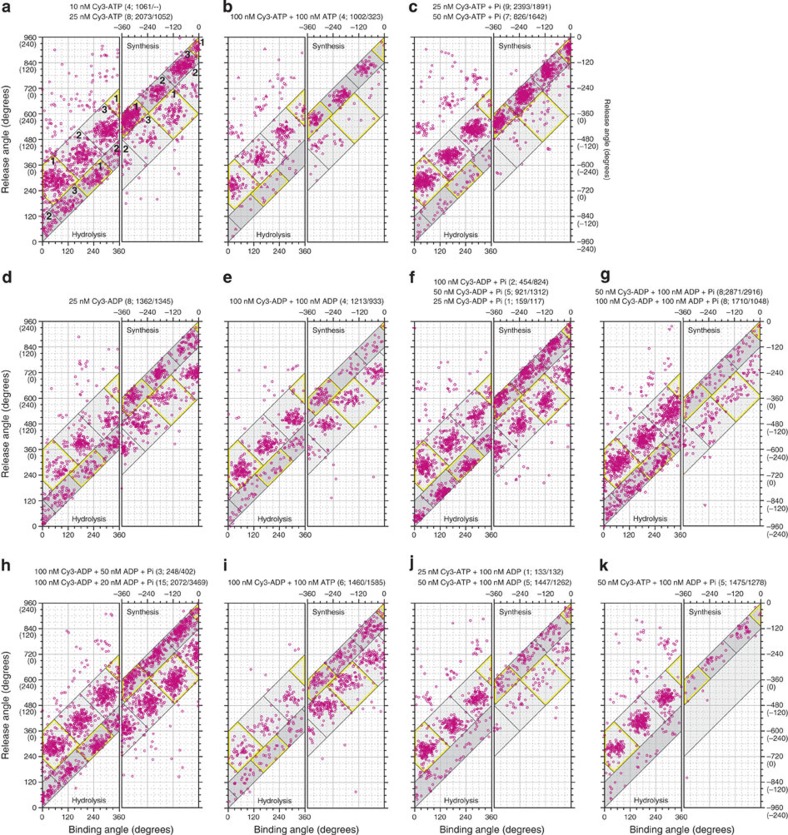

In Fig. 3, we extract the simplest binding events where the occupancy number changed as 0→1→0, and plot their θoff against θon. These were the major events, because [Cy3-nucleotide] was at most 100 nM, limited by the background fluorescence at high [Cy3-nucleotide]. The number of binding events per 120° rotation, that is, the events per catalytic site per turn, averaged <0.3 in all experiments. Light-grey zones in Fig. 3 indicate bindings for ~240° (120°≤|θoff−θon|<360°), which we call long bindings, and dark-grey zones short bindings (0°≤|θoff−θon|<120°). The two types of binding are also seen in time courses (Fig. 1c,d, and Supplementary Fig. S1). Longer bindings (360°≤|θoff−θon|) likely represent an overlap of two events. Close inspection of Fig. 2 suggests that many of the events other than the simplest ones can be explained as overlaps of long simple bindings (0→1→0 for ~240°) in different sites with a phase difference of a multiple of ~120°. This is more clearly seen in Fig. 4, which also indicates overlaps of long and short bindings when short bindings are frequent (for example, in panel d, see light pink for 0→1→2 1 and orange for 0→1→2→1

1 and orange for 0→1→2→1 0).

0).

Figure 3. Angular distributions of simple binding events.

(a) Cy3-ATP. Binding (θon) and release (θoff) angles are shown for simple events (site occupancy number 0→1→0). The nucleotide conditions shown at top; the number of molecules observed and rotations in the hydrolysis/synthesis directions in parentheses. Left and right panels, hydrolysis (θ increases) and synthesis (θ decreases) rotations. Light-grey zones, long bindings (120°≤|θoff−θon|<360°); dark-grey zones, short bindings (0°≤|θoff−θon|<120°). Yellow lines enclose events assigned to site 1; other sites are numbered. (b) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ATP. (c) Cy3-ATP with 10 mM Pi. (d) Cy3-ADP. (e) Cy3-ADP+unlablled ADP. (f) Cy3-ADP with 10 mM Pi. (g,h) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi. (i) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ATP. (j) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP. (k) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi. Site identifications are indicated in a.

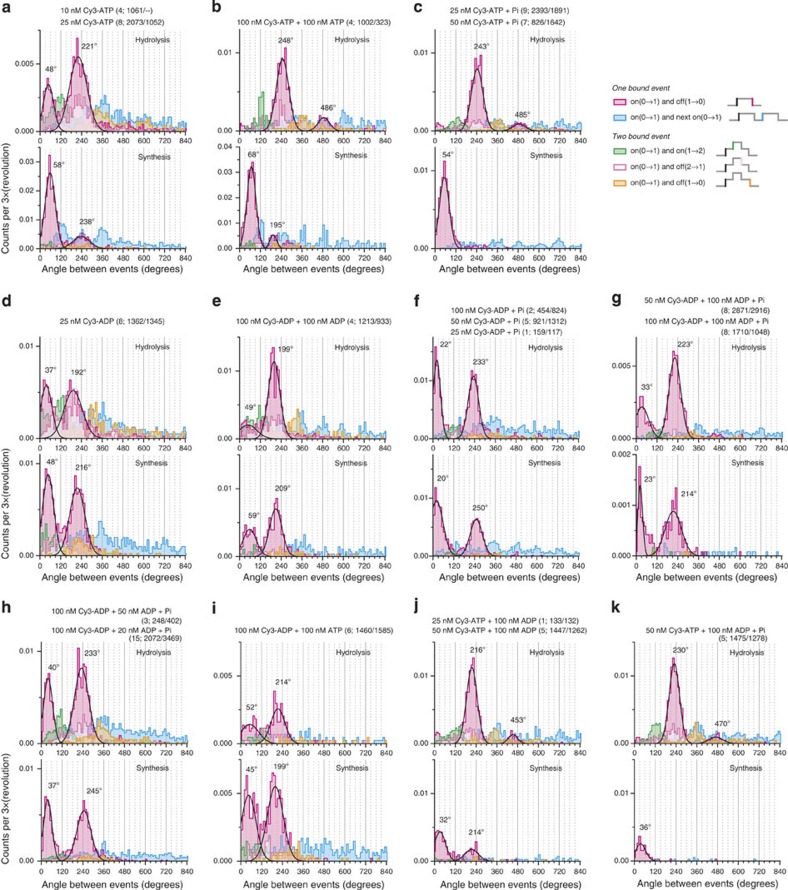

Figure 4. Histograms of the angular intervals between events.

(a) Cy3-ATP. For each sequence defined on the right of c (same as in Fig. 2), the angle between the first on event (black) and a subsequent event (colour coded) was scored and binned at 10° intervals. The nucleotide conditions and the numbers of molecules and rotations in the hydrolysis/synthesis directions in parentheses are indicated at the top. Major peaks in the magenta histograms for the simple events are fitted with a Gaussian distribution and the peak angles are indicated. (b) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ATP. (c) Cy3-ATP with 10 mM Pi. (d) Cy3-ADP. (e) Cy3-ADP+unlablled ADP. (f) Cy3-ADP with 10 mM Pi. (g,h) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi. (i) Cy3-ADP+unlabelled ATP. (j) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP. (k) Cy3-ATP+unlabelled ADP with 10 mM Pi. Note that, for the simple events in magenta, long bindings for ~240° and short bindings for <120° are conspicuous in most histograms. The next small peak at ~480° presumably results from a ~240° binding on one site followed by another ~240° binding on a different site, with a very short (<3 video frames) overlap or intermission that we ignore in the analysis. For Cy3-ATP in hydrolysis rotation, the addition of unlabelled ATP (b), Pi (c), unlabelled ADP (j), or unlabelled ADP and Pi (k) all result in the suppression of short bindings. The trend is similar for Cy3-ADP in hydrolysis rotation (d,e,g) except that Pi does not suppress short bindings (f,h) and unlabelled ATP suppresses both long and short bindings (i). For Cy3-ATP in synthesis rotation, short bindings predominate with Cy3-ATP alone (a), and the addition of unlabelled ATP (b), Pi (c), or unlabelled ADP and Pi (k) all enhance this trend by suppressing long bindings, Pi being most effective (c,k). Unlabelled ADP suppresses both long and short bindings (j). For Cy3-ADP in synthesis rotation, long and short bindings are suppressed to more or less similar extents by Pi or unlabelled ADP or ATP (d–h).

Below, we analyse the major, simplest events obtained in the absence of an unlabelled nucleotide (Fig. 3a,c,d,f) to estimate the rate constants of binding and release of Cy3-nucleotides. Suppression of Cy3 binding by unlabelled nucleotides (Fig. 4) gives information about the kinetics of unlabelled nucleotides, which we discuss at the end.

Site assignment

To calculate the rate constants of binding (kon) and release (koff) of a Cy3-nucleotide as the function of the bead (γ) angle θ, we must assign each event in Fig. 3 to one of the three catalytic sites. There are three clusters in the long binding (light grey) and short binding (dark grey) zones in Fig. 3, which we separate by the oblique lines and attempt to assign to the three catalytic sites. Longer bindings (360°≤|θoff−θon|) likely represent an overlap of two events, and we ignore these rare events in our analysis.

The long bindings of Cy3-ATP in hydrolysis rotation match the basic reaction scheme and the behaviour of Cy3-ATP in spontaneous (unforced) rotation15. Thus, we assign the yellow squares in Fig. 3a,c, hydrolysis panels, to site 1 defined as the site that waits for ATP at 0° in spontaneous rotation, and the other two squares to sites 2 and 3. The on angles in the forced rotation are shifted to higher angles than the ATP-waiting angles, but rotation in the hydrolysis direction is expected to increase the affinity for ATP4, as indeed indicated experimentally23,24,25. A site that binds ATP will also bind ADP, and thus we adopt the same assignment for Cy3-ADP. For ATP synthesis, we surmise that it would basically be the reverse of hydrolysis reaction. Then the long bindings of Cy3-ADP in the presence of Pi (Fig. 3f) are the expected ones, and site 1 should be the yellow square where Cy3-ADP is bound around −120° (=240°) and is released (presumably as Cy3-ATP) around −360° (=0°). Corresponding long bindings of Cy3-ATP were rare (Fig. 3c), as would be expected for efficient ATP synthesis. The other choice for synthesis in Fig. 3f, the short bindings in the dark zone, would be too short to complete the synthesis reaction beginning with binding of ADP and Pi and ending in ATP release. Other long binding clusters in synthesis are assigned after Fig. 3f.

We note in Fig. 3 that a short binding cluster in the dark zone finds a matching long binding cluster in the light zone in the horizontal direction, but not vertically. The horizontal pair shares the off angles but not on angles (Supplementary Fig. S2). Our interpretation is that the pair belongs to the same site (yellow rectangles belong to site 1): when a site that is to accommodate a nucleotide for ~240° happens to be vacant, owing to failure in the initial binding or due to early release of the bound nucleotide, the site permits another chance of binding towards the end of the ~240° period. In principle, short binding could also occur at the beginning of the ~240° period, but we do not see a vertical match in Fig. 3. Probable reasons are that we ignored very short bindings (<0.1 s) and that, at the beginning, rotation increases the affinity for the nucleotide, making immediate release difficult. The kon and koff estimated on the basis of these assignments are largely consistent between long and short bindings.

For short bindings, we assume that the nucleotide remains unchanged: Cy3-ATP is released as Cy3-ATP, and Cy3-ADP as Cy3-ADP. For long bindings, we assume hydrolysis or synthesis when the conditions are proper: Cy3-ATP is released as Cy3-ADP in hydrolysis rotation whether Pi is present or not, Cy3-ADP as Cy3-ATP in synthesis rotation in the presence of Pi, and no change in other circumstances.

Rate constants and affinities

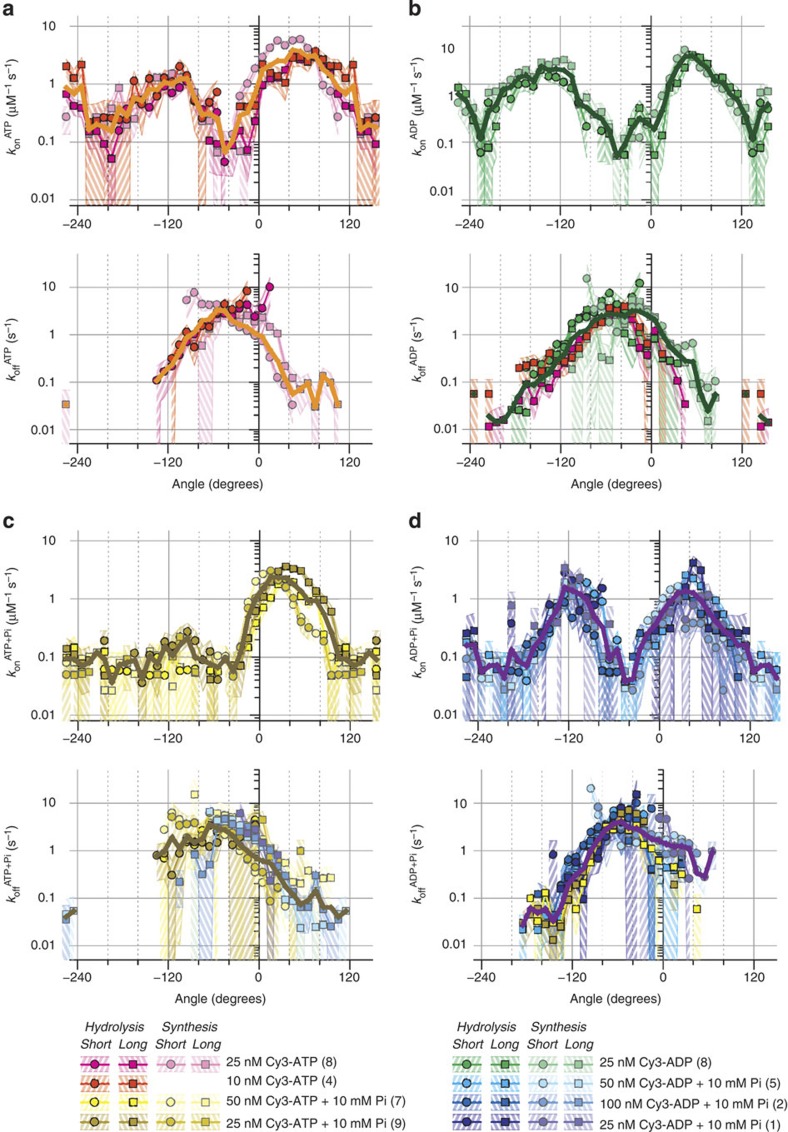

For the long and short binding clusters for each site, we count the number of on and off events per Δθ (=10°) as functions of θ. Assuming that the three sites are equivalent, we then gather all counts into site 1 by shifting θ for site 2 by −120° and θ for site 3 by −240°. To obtain kon(θ), we divide the on counts by the total observation time for the angular interval Δθ and then by [Cy3-nucleotide]. The time the site is already occupied should be subtracted from the observation time, but we do not apply this correction because the occupancy is below 0.3: correction up to 30% is insignificant in the results below on a logarithmic scale. For koff(θ), we divide the off counts by the total time the site was occupied. The results in the absence of an unlabelled nucleotide, which were calculated from Fig. 3a,c,d,f, are shown in Fig. 5, with the shades indicating the statistical error at confidence level of 68%.

Figure 5. Rate constants for binding (kon) and release (koff) in site 1.

(a) Rate constants for Cy3-ATP. (b) Cy3-ADP. (c) Cy3-ATP with 10 mM Pi. (d) Cy3-ADP with 10 mM Pi. Rotation directions, long and short bindings, and [Cy3-nucleotide] are distinguished (bottom); identities of leaving nucleotides as explained in text. Shade associated with each curve indicates purely statistical errors: relative errors of n−1/2 where n is the number of events observed per angular interval Δθ=10° (confidence level 68%; 95% at twice the shade width). Thick solid lines, the average with weights proportional to the total observation time (kon) or the total occupied time (koff).

Several rates are plotted in each panel of Fig. 5. These rates were estimated from different data sets, either from long or short events, either in the hydrolysis or synthesis rotations, and at different [Cy3-nucleotide], with the identity of leaving nucleotide (ATP or ADP) as assumed above. The curves all agree grossly with each other. Differences exist, some of which might be genuine, but limited statistics do not warrant their significance. Rather, we emphasize the general agreement and regard the differences among the curves as the measure of the reliability of our analyses. The agreement supports our site and leaving-nucleotide assignments above and supports the γ-dictator approximation that underlies these assignments.

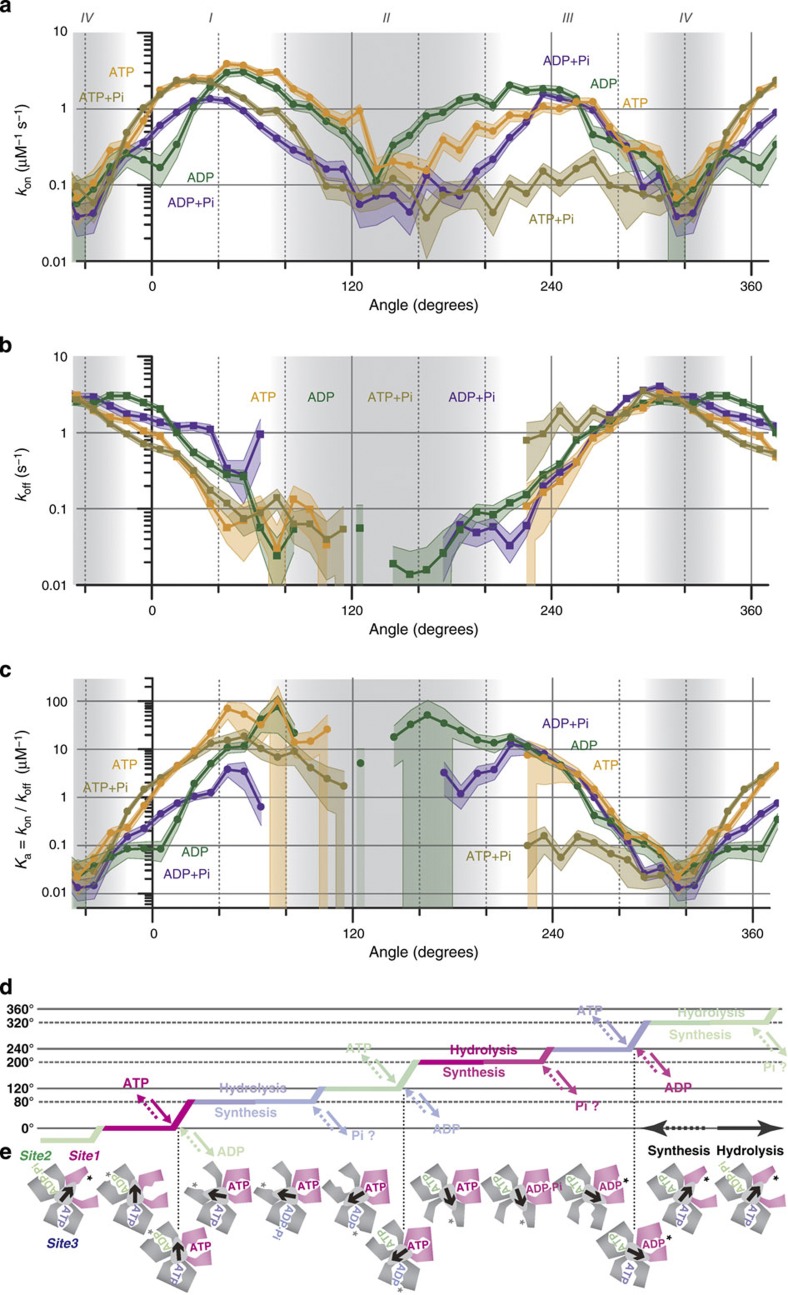

The thick solid lines in Fig. 5 show averages of the rate values and are replotted in Fig. 6a,b, from which we obtain the association constant Ka=kon/koff (Fig. 6c). We ignore the bumpy appearance of these curves owing to limited statistics. The nucleotide affinity (Ka) as well as the rate constants (kon and koff) change by orders of magnitude not digitally but gradually: the sites do not undergo discontinuous transition between high- and low-affinity states. The continuous nature accords with the induced fit mechanism6,26. Here, the fit and 'unfit' are forcibly induced by the rotation of the γ subunit, which is remote from the binding sites. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the overall protein conformation (γ angle) and the affinity, implying that the coupling between the local binding sites and the global conformation is strong compared with the intra-site energetics directly governing on and off. The tight coupling works in both directions: a nucleotide can induce global conformational changes (rotation), and nucleotide binding can be manipulated through the control of global conformation.

Figure 6. Summary of angle-dependent binding changes in site 1.

(a,b) Averaged rate constants for binding, kon (a), and for release, koff (b), from Fig. 5 for the indicated nucleotides ('Cy3-' is omitted). (c) Association constants calculated from a and b, Ka=kon/koff. Error shades in a and b represent relative errors of n−1/2 where n is the total event count per Δθ. Relative errors in c are (1/non+1/noff)1/2. Grey shades distinguish regions I–IV defined at the top. (d) Schematic time course of stepping rotation. Vertical axis is the γ angle, and horizontal axis time. Colours show the catalytic site in e where the indicated reaction occurs. Solid arrows, hydrolysis; dotted arrows, synthesis. Pi timings are yet unclear at present. (e) Schematic representation of the γ angle (arrow) and closing/opening of the three catalytic sites. Site 1 (magenta) is defined as the site that waits for ATP at 0° during stepping rotation. Some or all asterisks may be Pi.

Binding changes specific to F1

In region IV around 320°, koff is high and kon is low for all conditions examined, indicating a widely open, low-affinity catalytic site (Fig. 6). For F1, we have proposed that the crystal structures that bind two catalytic nucleotides would mimic the conformation of the 80°/200°/320° rotation intermediates6,15,27,28, as has also been suggested by other groups29,30, and one catalytic site in the crystals is indeed widely open without a nucleotide10. In Fig. 6e, we depict site 1 (magenta) as fully open at 320° (and −40°). Tryptophan quenching18 has indicated that, at 320°, the catalytic site is freely accessible from the medium, and that ATP or other nucleotides (ADP, AMPPNP or Pi) can enter the site with Ka for unlabelled ATP of 0.025 μM−1.

The other two catalytic sites in the crystals are fully closed, the '80°' site binding an ATP analogue AMPPNP and the '200°' site ADP in the original structure10. As expected, koff is low in region II. Progressive lowering of koff towards this region, either from −40° (through region I) or from 320° (through region III), suggests progressive open to closed conformational changes as the process of 'forcibly induced' fit6,26. Correspondingly, effective kon increases gradually from −40° towards ~40° and from 320° towards ~240° (except for ATP+Pi, see below) as the site becomes more fit for nucleotides. Further rotation from ~40° or ~240° into the fully closed region II, however, reduces kon. A fully closed site will not readily admit a nucleotide. Yet further rotation past the fully closed region gradually reopens the site (forced 'unfit'), and if the site is empty, the now partially open site will allow binding of a medium nucleotide; this is how we envisage the short binding events in Fig. 3. Ka should be highest in the fully closed conformation, but paucity of off events hampers its estimation.

The koff profiles are similar between ATP and ADP in the presence and absence of Pi, and are largely symmetric about region II or IV. The kon profiles, in contrast, are less symmetric and display nucleotide and Pi dependences. The kon for ATP is somewhat higher than for ADP in the region 0°–140°, in the presence and absence of Pi, and the trend is reversed in 140°–240°, suggesting a transition from an ATP-favouring to an ADP-favouring site. In spontaneous hydrolysis rotation, cleavage of ATP to ADP and Pi occurs at 200° (refs 15,31,32,33), or 120° in some conditions34. The crystal grown in the presence of AMPPNP and ADP binds AMPPNP in the '80°' site and ADP in the '200°' site10. A gradual shift towards hydrolysis across 200° has recently been indicated for ATP-γ-S25.

Ten-millimolar Pi reduced kon (and Ka) in and around region II. Of particular importance is the large and ATP-specific decrease of kon around 240°, which is essential for efficient ATP synthesis. The Pi that elicits this effect is not tightly bound and millimolar Pi is required for the reduction, because the medium without added Pi already contained 10-μM contaminant Pi. That is, the association constant of the empty site for Pi is below 105 M−1 (but above 102 M−1) in the region between ~40° and ~320° (likely higher if ADP is already bound). Between −40° and 40°, Pi exerts little effect, implicating even lower affinity for Pi. The pathways of catalytic site closure on the two sides of the fully open conformation at 320° (=−40°) are asymmetric.

Rotational catalysis

Figure 6 explains how the spontaneous hydrolysis rotation occurs in F1 and how forced reverse rotation leads to ATP synthesis. In the absence of an external torque, site 1 waits for ATP at 0°, where Ka as well as kon for ATP is higher than those for ADP. Site 1 thus preferentially binds ATP. The kon for Cy3-ATP of ~1×106 M−1 s−1 at 0° is consistent with the 120°-stepping rate of unforced rotation driven by Cy3-ATP of 1.6×106 M−1 s−1 (ref.15); note the thermal fluctuation in the positive direction assists ATP binding. The kon for unlabelled ATP is an order of magnitude higher, (2–3)×107 M−1 s−1 (refs 13,35,36). ATP binding sets up a downhill potential energy for γ rotation4,14, and γ starts to rotate in the positive (hydrolysis) direction. The rotation increases kon for ATP while decreasing koff (Fig. 6a,b), preventing the release of ATP. Further rotation fully closes site 1. Rotation beyond 120° requires binding of another ATP at site 2. Then γ pauses for ~1 ms at 200° to wait for ATP cleavage and another reaction, possibly Pi release15. At 240° a third ATP binds to site 3, and further rotation decreases the affinity of site 1 for ADP while increasing its off rate (Fig. 6b,c), resulting in the ADP release from site 1. The koff for Cy3-ADP is not high enough to explain the spontaneous rotation rate of >102 revolutions s−1 with unlabelled ATP14. Cy3-nucleotides appear sluggish compared with unlabelled nucleotides both for on and off processes.

For ATP synthesis, reverse rotation of γ from 320° towards 240°, forced by an external torque, augments the affinity of site 1 for both ATP and ADP (Fig. 6c). Binding of ATP would be a failure for synthesis, but Pi blocks ATP. The Michaelis–Menten constant KmPi for Pi in ATP synthesis is 0.55 mM at 30 °C for the thermophilic FoF137. Efficient synthesis thus requires millimolar Pi, which will ensure ADP binding over ATP. The loosely bound Pi likely resides in the site indicated by an asterisk in Fig. 6e, which may exchange with medium Pi before conjugation to ADP. The on rate for Cy3-ADP around 240° is ~2×106 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 6a), implying a binding rate of ~20 s−1 at KmADP for synthesis of 13 μM (ref. 37). The maximal rate of ATP synthesis is likely higher37, but we expect faster binding of unlabelled ADP than Cy3-ADP. After phosphorylation of ADP in the closed region II, the remaining task is to release the tightly bound ATP. Rotation towards and beyond 0° ensures Cy3-ATP release in the presence of up to ~10-μM medium Cy3-ATP (Fig. 6c). The off rate for Cy3-ATP is not high enough for efficient synthesis, but unlabelled ATP would be released faster (and Ka may be lower to allow ATP release in >10 μM ATP).

Kinetics of unlabelled nucleotides

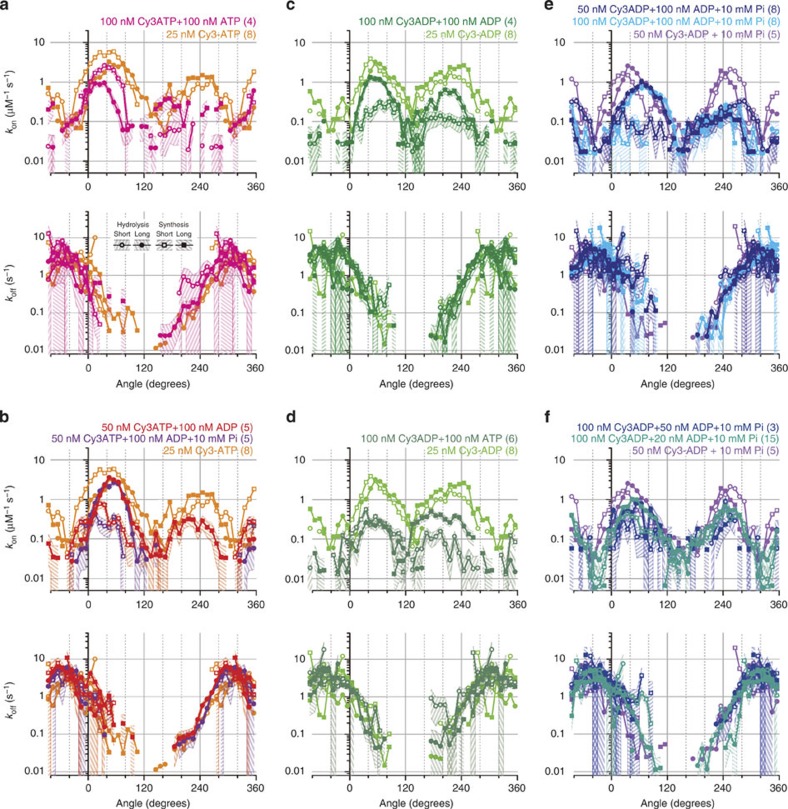

Unlabelled nucleotides might show qualitatively different behaviours, in addition to the faster kinetics already mentioned. Also, the experiments were done under conditions where at most one of the three catalytic sites was occupied by a nucleotide, whereas in spontaneous hydrolysis rotation of F1, at least two sites are always occupied15,18 and the same likely applies to synthesis. To address these concerns, we estimated kon and koff of Cy3-nucleotides in the presence of 100 nM unlabelled ATP or ADP; unlabelled ATP at 100 nM supports normal hydrolysis rotation36, with two sites filled18. Figure 7 indicates that binding kinetics of unlabelled nucleotides are basically similar to those of Cy3-nucleotides, and that binding of unlabelled nucleotides in other sites does not alter the kinetics of Cy3-nucleotides in a significant manner.

Figure 7. Effects of unlabelled nucleotides on the binding kinetics of Cy3-nucleotides in site 1.

(a–f) Effect of unlabelled ATP on kon and koff for Cy3-ATP (a); unlabelled ADP with or without Pi, for Cy3-ATP (b); unlabelled ADP, for Cy3-ADP (c); unlabelled ATP, for Cy3-ADP (d); unlabelled ADP and Pi, for Cy3-ADP (e,f). Simple events for all nucleotide conditions in Fig. 3 were analysed without taking into account the possibility that the target site is already preoccupied by an unlabelled nucleotide. The nucleotide conditions and the number of molecules observed in parentheses are indicated at the top. Other conditions (rotational direction and long and short bindings) are defined in a. Shades indicate statistical errors: relative errors of n−1/2 where n is the number of events observed per Δθ=10°. Unlike Fig. 5, the off rates here are not classified according to the identities of leaving nucleotides.

In Fig. 7, we note that the koff of Cy3-nucleotides is not affected by the presence of unlabelled nucleotides, within the limited statistics. This is not a trivial observation and supports the γ-dictator approximation: the off rate from a particular site does not depend on whether the other sites are occupied or not. In other words, multisite catalysis (more than one of the three catalytic sites are occupied) and the so-called uni-site catalysis do not differ significantly, at least as far as koff is concerned, if the γ angle is controlled externally.

Second, we see a reduction of kon in the presence of unlabelled nucleotides. kon here does not represent simple competition where Cy3- and unlabelled nucleotides compete impartially for a vacant site: an unlabelled nucleotide may have preoccupied the target site by entering there at an early stage of rotation. Thus, the expected scenario for a long (~240°) binding of an unlabelled nucleotide is that, at the beginning of rotation when the affinity of the unlabelled nucleotide for that site is still low, both Cy3- and unlabelled nucleotides compete impartially. As rotation proceeds and the site closes, an unlabelled nucleotide tends to occupy the site and remains there until its' off rate increases upon reopening. Thus, the short bindings of Cy3-nucleotides, which we presume to occur during the reopening stage, will be blocked more severely compared with long bindings that begin at early stages of site closing. If the affinity of the unlabelled nucleotide is high from an early stage of site closing, as would be expected for unlabelled ATP in hydrolysis rotation, long binding of Cy3-nucleotides will also be severely blocked except at the very beginning of site closing. Most of the results in Fig. 7 are consistent with these expectations: reduction of kon by unlabelled nucleotide is larger for short bindings (open symbols) than for long bindings (closed symbols), and kon for long bindings is also severely reduced by unlabelled ATP as hydrolysis rotation proceeds from 0° towards 120° (Fig. 7a,d). The implication is that unlabelled nucleotides respond to site closing and opening essentially in the same fashion as Cy3-nucleotides. The lowered kon profiles are grossly consistent with the picture where the Cy3 kinetics are not affected by the presence of unlabelled nucleotides in other sites (γ-dictator approximation) and where the behaviours of unlabelled nucleotides do not differ qualitatively from those of Cy3-nucleotides.

A possible exception to the above interpretation, which may be ascribed to limited precision, is the relatively small reduction of short binding kon for Cy3-ATP by unlabelled ATP around 40°–80° (Fig. 7a). This would be explained if long bindings of unlabelled ATP in synthesis rotation are rare events, as for Cy3-ATP (best seen in Fig. 4a). Another possible exception is the effect of unlabelled ADP on Cy3-ADP binding in the presence of Pi (Fig. 7f also belongs to this case but the effect was small because [unlabelled ADP] was lower): in hydrolysis rotation, long bindings around 80°–120° and short bindings around 300° are both unsuppressed. We are not sure if this is significant beyond uncertainty, and we cannot provide an immediate explanation except to point out that ADP and Pi can bind simultaneously and thus a complicated behaviour is not unexpected.

Kinetics of unlabelled ATP around 0° have been reported25, with angular profiles qualitatively similar to Cy3-ATP but kon ~10 times higher and koff ~10 times lower. The low koff, estimated indirectly, is unexpected for rapid ATP synthesis. For physiologically competent ATP synthesis, the koff for unlabelled ATP should reach >~102 s−1 at some angles and Ka for ATP<10−3 μM−1.

Discussion

One can rotate the magnetic beads with a hand-held toy magnet. This manual operation changes the nucleotide affinity of the tiny molecular machine over four orders of magnitude or more (Fig. 6c). For ligand binding in general, the binding affinity and associated rate constants for a particular ligand have often been given unique values, even for nucleotide-driven molecular machines. Here, we show by manipulation that binding parameters change dramatically yet continuously and smoothly. Controlled slow manipulation such as with magnets may reveal continuous binding changes in other molecular machines as well, where the continuous nature is likely concealed behind rapid kinetics of unhindered reactions. Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments have shown that in FoF1-ATP synthase three distinct jumps of the rotor occur both during hydrolysis and synthesis38, which are forcibly slowed down by magnets in this study.

Manipulation remote from a binding site also reveals energetics between the local binding site and global conformation. From the association constant Ka, the binding free energy per molecule is calculated as ΔG0=−kBT·lnKa where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T the absolute temperature (kBT~4.1×10−21 J per molecule at room temperature). For F1, ΔG0 is a function of the γ angle θ, and ΔG0(θ) is given by Fig. 6c turned upside down (separations between horizontal lines correspond to kBT·ln10=2.3kBT=9.4×10−21 J per molecule). Global rotation changes the binding free energy for ADP and ATP each by kBT·ln104~10kBT (ten times the thermal energy); this much energy can be put into the molecular machine by the manual operation. The free energy needed to synthesize ATP under cellular conditions is ~20kBT (ref. 4).

The role of binding free energy in the operation of a molecular machine is best illustrated by considering potential energy that governs the mechanical conformational changes of the machine. For the case of F1-ATPase, one can think of the potential energy ψXYZ(θ) for γ rotation for given chemical states in the three catalytic sites (X, Y, Z=ATP, ADP, and so on)4. Rotation of γ in a given set of chemical states XYZ is driven or opposed by ψXYZ depending on whether ψXYZ is downhill or uphill in the rotation direction (torque on γ=−∂ψXYZ/∂θ). The angle-dependent affinity of site 1 for a nucleotide N we obtained in this work is related to the potential energy by ΔG0N(θ)=−kBT·lnKaN(θ)=ψNYZ(θ)−ψEYZ(θ), where E represents the empty state. In the γ-dictator approximation, ΔG0N(θ) is insensitive to YZ (nucleotide states of the other two sites). What we manipulate with magnets is θ, to change the nucleotide affinity ΔG0N(θ) by working against ψ. In ATP synthesis, we decrease θ across 240°, working against ψEYZ, to decrease ΔG0ADP (augment KaADP), and further across 0° against ψATP,YZ to increase ΔG0ATP (decrease KaATP). This is how we see Boyer's binding changes mechanism of ATP synthesis1,8. We have been able to embody the binding changes by giving gross pictures of the angle-dependent Ka(θ), or the differences in potential energies. A remaining challenge is to determine the individual potential ψXYZ(θ).

Methods

Chemicals and proteins

2′-O-Cy3-EDA-ATP and 2′-O-Cy3-EDA-ADP were used as fluorescent nucleotide analogues20,21, referred to here as Cy3-ATP and Cy3-ADP, respectively. The subcomplex α(C193S)3β(His10-tag at N terminus)3γ(S107C, I210C) derived from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified7,39, and the sole two cysteines on γ were biotinylated14. The sample was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Microscopy

Cy3-nucleotide was imaged with objective-type TIRF microscopy15 on an inverted microscope (IX70, Olympus) with a stable mechanical stage (KS-O, Chuukousha, Seisakujo), where the 532-nm laser beam (Millennia II, Spectra-Physics) was introduced from below through an objective (PlanApo ×100 NA 1.4, Olympus; made magnetization-free by custom order). Ordinary TIRF setup with a single laser beam, even if circularly polarized (unpolarized), leads to preferential excitation of those dye molecules with a transition moment perpendicular to the beam. For quantitative fluorescence, therefore, we illuminated the sample from all directions along a cone with circularly polarized laser beams (Fig. 1a). Laser power before the objective was typically 0.16 mW, which illuminated a sample area ~60 μm in diameter. Fluorescence was imaged with an intensified (VS4-1845, Videoscope) CCD camera (CCD-300T-IFG, Dage-MTI). Images of magnetic beads, illuminated with a halogen lamp, were separated from fluorescence by a dichroic mirror and captured with another CCD camera (CCD-300-RC, Dage-MTI). Fluorescence and bead images at the video rate of 30 frames s−1 were synchronously combined (Multi Viewer MV-24C, FOR-A) and recorded on a computer by an acquisition software (Video Savant, IO Industries). We analysed images using public-domain software (ImageJ, NIH) and in-house plug-ins. Rotary angles were calculated from the centroid of bead images14.

Electromagnets were composed of two opposing pairs of electromagnets made of soft iron and mounted on the microscope stage 18 mm above the sample15 (Fig. 1a). Magnetic beads were rotated at constant speed of 0.05–0.8 Hz in the magnetic field of 47–110 Gauss.

Flow chamber

Glass surfaces were functionalized with Ni-NTA (ref. 11): KOH-cleaned coverslips (32×24 mm, thickness No.1, Matsunami) were incubated in 2% (v/v) γ-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane (TSL8380, Momentive) in water containing 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid for 3 h at 90 °C, and treated with 0.1 M dithiothreitol for 30 min at 23 °C to reduce SH groups. 40 mg ml−1 maleimide-C3-NTA (Dojindo) was applied for 3 h at 23 °C, followed by incubation in 20 mM NiCl2 for 30 min at 23 °C. Modified coverslips were stored in water and used within a week. We also used simply silanized coverslips (dithiothreitol and subsequent treatments above omitted), which nonspecifically immobilized F1; the numbers of bound and rotating beads were indistinguishable from those with Ni-NTA, and the shift of stepping positions after long observation appeared less frequent.

We made flow chambers on a modified coverslip above by placing three greased spacers (Parafilm cover sheet) of ~50-μm thickness and an unmodified coverslip (18×18 mm) on top to form two 6-mm-wide chambers side by side. We infused one chamber volume (~5 μl) of 50 pM biotinylated F1 in buffer A (25 mM MOPS-KOH, 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0), waited for 2 min, and then infused 20 μl of buffer A and 20 μl of 5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin in buffer A. We then infused 20 μl of streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads (Sera-Mag Magnetic Streptavidin, nominal diameter 0.8 μm, Seradyn) from which particles >~0.5 μm had been removed by centrifugation at 7,800 g for 8 min. After 30 min, we infused thrice 20 μl of buffer A, and then 20 μl of 2.5 mg ml−1 biotin-labelled bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent adsorption of Cy3-nucleotide on the surface of magnetic beads. Before the simultaneous observation, we observed spontaneous stepping rotation at 60 nM ATP by infusing twice 20 μl of buffer B (buffer A with KCl at 25 mM) containing 60 nM ATP and an ATP-regenerating system (1.25 mM creatine phosphate and 0.1 mg ml−1 creatine kinase, Roche).

Rotation assay

After the observation of rotation at 60 nM ATP, the ATP was completely removed by washing the chamber eight times with 20 μl of buffer B. We then infused four times 20 μl of observation buffer containing buffer B plus 0.5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mg ml−1 glucose-oxidase (Wako), 300 U ml−1 catalase (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.25 mg ml−1 glucose and a desired amount of Cy3-ATP/ADP in the presence and absence of 10 mM Pi, unlabelled ATP, or unlabelled ADP, and started observation under the microscope. Pi contamination of the observation buffer in the absence of added Pi was 9.3±0.1 μM (EnzChek phosphate assay, Invitrogen), mostly from glucose oxidase and catalase. For the observation in the mixture of Cy3-ATP and unlabelled ATP, the prior observation at 60 nM ATP was omitted, and the ATP-regenerating system was contained in the observation buffer. After all simultaneous observations, we again observed the spontaneous rotation of the target F1 at 60 nM ATP. Observations were made at 23.0±0.1 °C in a clean room.

Binding (on) and release (off) of a Cy3-nucleotide was judged as the transition of the occupancy number in the fluorescence intensity record (Fig. 1c,d, and Supplementary Fig. S1). We identified on and off events when the occupancy numbers before and after a transition both remained unchanged for three video frames (0.1 s) or more, discounting very short events. The on and off timings were assigned to the middle of the transition, within two frames, and corresponding binding (θon) and release (θoff) angles were read from the bead rotation record.

Selection of molecules for analysis

Before the simultaneous observation, we preselected beads to be analysed. During the initial observation of stepping rotation with 60 nM unlabelled ATP in the absence of a magnetic field, we marked those beads that gave a trace close to an equilateral triangle (green dots in insets of Fig. 1c,d, and Supplementary Fig. S1). We then switched on the magnets to select those beads that gave a circular trace (black dots) concentric with the triangle, deselecting those beads that reoriented vertically in response to the magnetic field. We further let the selected beads rotate at 0.2 Hz in both directions each for 10 min to deselect those that changed the stepping positions (loosely attached F1), that stopped (by, for example, attachment to the glass surface) or that floated into solution. Then, we flowed in Cy3-nucleotide and turned on fluorescence excitation to start the simultaneous observation of Cy3 kinetics and rotation. At the end, we turned off the magnets and changed the solution to 60 nM unlabelled ATP to see if the stepping positions remained unchanged. About 30% of the preselected beads passed this last test (shift within ±12°, ±6° s.d.), whereas ~40% had shifted the positions and the rest failed to rotate because of light-induced inactivation (the laser power was minimized for this reason), adhesion to the glass surface or detachment during solution exchange. Only those F1 molecules that passed the last test were subjected to analysis.

Author contributions

K.A. designed the research; K.O. prepared the Cy3-nucleotides; T.N. helped with the optics; K.A. conducted the experiments and performed the analysis; K.A. wrote the paper together with K.O., T.N., M.Y. and K.K.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Adachi, K. et al. Controlled rotation of the F1-ATPase reveals differential and continuous binding changes for ATP synthesis. Nat. Commun. 3:1022 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2026 (2012).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Kanda, R. Shimo-Kon, S. Furuike, K. Shiroguchi, Y. Onoue, M. Shio, T. Masaike and members of Nishizaka, Kinosita and Yoshida labs for technical assistance, critical reading and discussion, and S. Takahashi, K. Sakamaki and M. Fukatsu for encouragement and lab management. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research to K.K. and for Young Scientists (B) to K.A. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- Boyer P. D. The binding change mechanism for ATP synthase—some probabilities and possibilities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1140, 215–250 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Muneyuki E. & Hisabori T. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 669–677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior A. E., Nadanaciva S. & Weber J. The molecular mechanism of ATP synthesis by F1F0-ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1553, 188–211 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinosita K. Jr., Adachi K. & Itoh H. Rotation of F1-ATPase: how an ATP-driven molecular machine may work. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33, 245–268 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge W., Sielaff H. & Engelbrecht S. Torque generation and elastic power transmission in the rotary FOF1-ATPase. Nature 459, 364–370 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K. et al. Chemo-mechanical coupling in the rotary molecular motor F1-ATPase. In Single Molecule Spectroscopy in Chemistry, Physics and Biology, Vol 96 (eds Gräslund, A., Rigler, R. & Widengren, J.) 271–285 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Noji H., Yasuda R., Yoshida M. & Kinosita K. Jr. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature 386, 299–302 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P. D. & Kohlbrenner W. E. The present status of the binding-change mechanism and its relation to ATP formation by chloroplasts. In Energy Coupling in Photosynthesis (eds Selman, B.R. & Selman-Reimer, S.) 231–240 (Elsevier, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Oosawa F. & Hayashi S. The loose coupling mechanism in molecular machines of living cells. Adv. Biophys. 22, 151–183 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams J. P., Leslie A. G. W., Lutter R. & Walker J. E. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370, 621–628 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H. et al. Mechanically driven ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase. Nature 427, 465–468 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondelez Y. et al. Highly coupled ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase single molecules. Nature 433, 773–777 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda R., Noji H., Kinosita K. Jr. & Yoshida M. F1-ATPase is a highly efficient molecular motor that rotates with discrete 120° steps. Cell 93, 1117–1124 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda R., Noji H., Yoshida M., Kinosita K. Jr. & Itoh H. Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature 410, 898–904 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K. et al. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F1-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell 130, 309–321 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuike S. et al. Axle-less F1-ATPase rotates in the correct direction. Science 319, 955–958 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchihashi T., Iino R., Ando T. & Noji H. High-speed atomic force microscopy reveals rotary catalysis of rotorless F1-ATPase. Science 333, 755–758 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimo-Kon R. et al. Chemo-mechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by catalytic site occupancy during catalysis. Biophys. J. 98, 1227–1236 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R., Iino R. & Noji H. Phosphate release in F1-ATPase catalytic cycle follows ADP release. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 814–820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oiwa K. et al. Comparative single-molecule and ensemble myosin enzymology: sulfoindocyanine ATP and ADP derivatives. Biophys. J. 78, 3048–3071 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oiwa K. et al. The 2′-O- and 3′-O-Cy3-EDA-ATP(ADP) complexes with myosin subfragment-1 are spectroscopically distinct. Biophys. J. 84, 634–642 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu T., Harada Y., Tokunaga M., Saito K. & Yanagida T. Imaging of single fluorescent molecules and individual ATP turnovers by single myosin molecules in aqueous solution. Nature 374, 555–559 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe-Nakayama T. et al. Effect of external torque on the ATP-driven rotation of F1-ATPase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366, 951–957 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iko Y., Tabata K. V., Sakakihara S., Nakashima T. & Noji H. Acceleration of the ATP-binding rate of F1-ATPase by forcible forward rotation. FEBS Lett. 583, 3187–3191 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R. et al. Mechanical modulation of catalytic power on F1-ATPase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 86–92 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D. E. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 44, 98–104 (1958). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda R. et al. The ATP-waiting conformation of rotating F1-ATPase revealed by single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9314–9318 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaike T., Koyama-Horibe F., Oiwa K., Yoshida M. & Nishizaka T. Cooperative three-step motions in catalytic subunits of F1-ATPase correlate with 80° and 40° substep rotations. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1326–1333 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sielaff H., Rennekamp H., Engelbrecht S. & Junge W. Functional halt positions of rotary FOF1-ATPase correlated with crystal structures. Biophys. J. 95, 4979–4987 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno D. et al. Correlation between the conformational states of F1-ATPase as determined from its crystal structure and single-molecule rotation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20722–20727 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro K. et al. Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40° substep rotation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14731–14736 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizaka T. et al. Chemomechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 142–148 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga T., Muneyuki E. & Yoshida M. F1-ATPase rotates by an asymmetric, sequential mechanism using all three catalytic subunits. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 841–846 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro K., Muneyuki E. & Yoshida M. An alternative reaction pathway of F1-ATPase suggested by rotation without 80°/40° substeps of a sluggish mutant at low ATP. Biophys. J. 90, 1028–1032 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K. et al. Stepping rotation of F1-ATPase visualized through angle-resolved single-fluorophore imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7243–7247 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki N. et al. One rotary mechanism for F1-ATPase over ATP concentrations from millimolar down to nanomolar. Biophys. J. 88, 2047–2056 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga N., Kinosita K. Jr., Yoshida M. & Suzuki T. Efficient ATP synthesis by thermophilic Bacillus FoF1-ATP synthase. FEBS J. 278, 2647–2654 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann B., Diez M., Zarrabi N., Gräber P. & Börsch M. Movements of the ɛ-subunit during catalysis and activation in single membrane-bound H+-ATP synthase. EMBO J. 24, 2053–2063 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji H. et al. Purine but not pyrimidine nucleotides support rotation of F1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25480–25486 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2