Abstract

Introduction

Using wireless devices may potentially transform delivery of primary care services in sickle cell disease (SCD). The study examined text message communications between patients and an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) and the different primary care activities that emerged using wireless technology.

Methods

Patients (n=37; mean age 13.9 ± 1.8 years; 45.9% males; 54.1% females) engaged in intermittent text conversations with the advanced practice registered nurse as part of the Wireless Pain Intervention Program. Content Analyses were used to analyze the content of text message exchanges between patients and the APRN.

Results

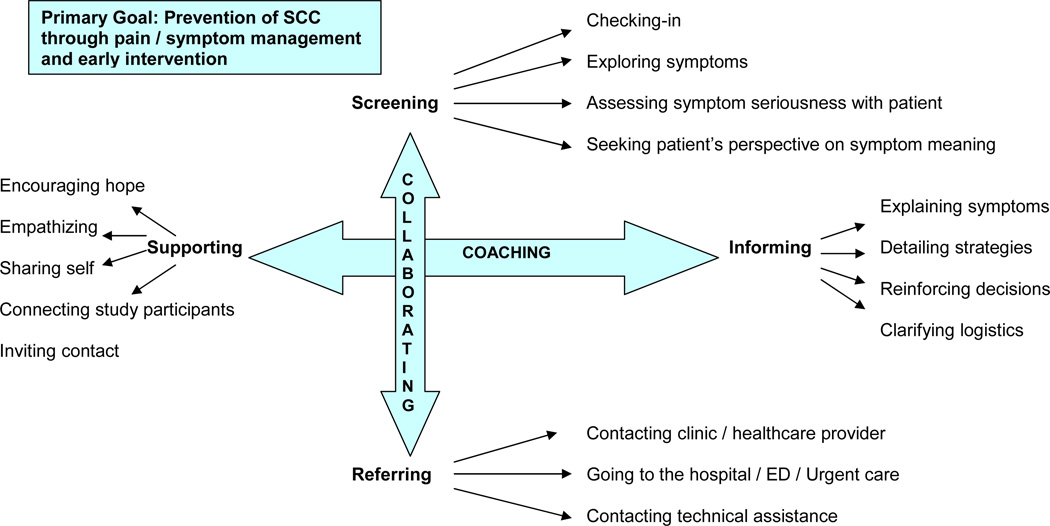

The primary care needs that emerged were related to pain and symptom management and sickle cell crisis prevention. Two primary care categories (collaborating and coaching), four primary care subcategories (screening, referring, informing, supporting), and 16 primary care activities were evident in text conversations.

Discussion

The use of wireless technology may facilitate screening, prompt management of pain and symptoms, prevention or reduction of SCD related complications, more efficient referral for treatments, timely patient education, and psychosocial support in children and adolescents with SCD.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, pain, symptoms, wireless technology, smartphone, text message communications

INTRODUCTION

Effective communication between providers and patients is needed to improve health outcomes and delivery of care (Chaudhry, et al., 2006; Institute of Medicine, 2001). Children and adolescents with sickle cell disease (SCD) require ongoing medical care, and often depend on their parents or caregivers to mediate the required communications with care providers. They may not be comfortable with or be able to ask the right questions or provide relevant information to care providers. They tend to answer only what they are asked, and may not be given very much information during health care visits (Ngo-Metzger, et al, 2010). While patient-centered approaches and interactive communications may potentially improve the quality of care delivery (Chaudhry, et al., 2006; IOM, 2001), these approaches have not yet been well implemented in the continuum of care for children and adolescents with SCD.

Recent advances in wireless technology may facilitate patient-centered approaches and establish interactive communications that were not previously possible (Puccio, et al., 2001). The use of mobile phones, smartphones, and other wireless devices (PDA, iPAD, netbooks) is increasingly more common among children and adolescents which may empower them to communicate directly with care providers. This enhanced communication would then encourage them to be more involved in decisions regarding their own care, rather than heavily relying on their parents or caregivers as they transition into young adults (Gentles, et al., 2010).

Lenhart, Madden, and Hitlin (2005) found that an overwhelming majority (84%) of the 1100 adolescents in their survey reported owning at least one personal media device, such as a desktop or laptop computer, a cell phone or a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), and almost one third (31%) used them to access health information. About half (45%) reported having a cell phone, and one third (33%) used it to send text messages. Children and adolescents are technology savvy and have used instant messaging and text messaging for conversations with other technology-savvy peers, as well as to communicate with parents (Lenhart, et al., 2005).

Marciel and colleagues (2010) designed a web-enabled cell phone intervention that provided information about management of symptoms and social support to improve to treatment adherence among adolescents with cystic fibrosis. The intervention included visual, tactile, auditory, and interactive modes of communication, and focused on peer-to-peer support using a web application. Web-site moderators provided suggestions about communications and referrals provided to relevant mental health professionals. Thus a combination of phone and web-based tools provided the adolescents with individualized information about management of symptoms in cystic fibrosis (Marciel, Saiman, Quittell, et al., 2010).

Health care and information services may be delivered and enhanced directly through the use of wireless technology. Gentle and colleagues (2010) recently reviewed studies that implemented interventions featuring different modes of wireless technology (e.g., Internet, telephone, email, short message service). They found that wireless technology was used to facilitate different functions (e.g., support, medication management, education, and monitoring).

The use of wireless technology may be an effective strategy for meeting one of the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2001) that advocates for patient-centered care and increased access to care in a more timely manner. The IOM Report recommends that care should be provided whenever patients need it and providers should be available at all times (24 hours a day, every day). It also recommends that care should be made more accessible by offering it over the Internet, by telephone, and by other means in addition to face-to-face visits (IOM, 2001).

As part of our Wireless Pain Intervention Program that examined pain and symptoms in children and adolescents with SCD, we utilized smartphones as a medium for facilitating communications between an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) and children and adolescents with SCD. The purpose of this study was to examine how patients with SCD communicated with a health care provider [APRN] while using smartphones and to examine the different health care provider activities that resulted from the interactions using content analyses of their text message communications.

METHODS

Design

Children and adolescents with SCD were invited to enroll in the Wireless Pain Intervention Program and were asked to complete pain and symptom measures using a smartphone to access a web-based e-Diary twice daily (Jacob, et al., 2011). An APRN with expertise in SCD remotely monitored the e-Diary entries, responded to alert messages based upon preprogrammed parameters, and responded to text messages sent by patients (Duran, et al., 2010). The results presented in this portion of the study represent the content analyses of the text message exchanges between patients and the APRN between April 2010 and December 2010.

Sample & Setting

The Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California (SCDFC), a community-based organization in Southern California distributed study information flyers and invited patients from their programs to be part of the study. This organization serves approximately 5000 people with SCD across several regions of Southern California (Ontario, Corona, San Diego, Los Angeles). The population SCDFC serves is predominantly African-American (90%), or Hispanic and several other ethnic origins (10%).

Eligibility criteria included children and adolescents who were 10 to 17 years of age, with a known diagnosis of SCD, and were able to speak, read, write, and understand English. In addition, they were able to use the computer and smartphone, and have a computer available either through home, a local library, or school. Exclusion criteria included children with any major cognitive or neurological impairment (as reported by parents) that affected their ability to understand and complete the study procedures.

Data Analysis

All text messages were downloaded into a word file and arranged chronologically according to each patient. A total of 767 text messages formed the research data set. After three authors carefully read all text messages, the text messages were segmented into specific text conversations. Text conversations were defined as a meaningful and coherent text message or exchange of text-messages between patient and APRN. A total of 163 text conversations were identified and numbered for analysis. All text messages were then read within each text conversation numerous times. Email exchanges, face to face meetings as well as phone conferences occurred between three researchers to clarify comments, thoughts, and categories until agreement occurred about the findings.

The categorization process included the following steps: 1) induction to extract an organizing framework and create structural categories (Shkedi, 2005); 2) arrangement of text conversations into an excel spreadsheet according to the structural categories (Meyer & Avery, 2009); 3) examination of content within each categorized text conversation (Swallow, Newton, & Van Lottum, 2003) and inductive coding of all primary care actions and patient responses (Saldaña, 2009); 4) mapping and diagramming to expand understanding about how different data elements, such as codes and categories, were related (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Researchers conferred throughout the data analysis process to develop the final primary care action code and category lists and diagram (Figure 1). Once researchers were satisfied that the action code list accurately represented the content of text conversations, we applied the code list to all text conversations, and performed frequency counts.

Figure 1.

Primary Care Activities Emerging in Text Conversations with Patients Living with SCD

RESULTS

Patients (n=37) engaged in intermittent text conversations with the APRN (Table 1). The mean age of these patients was 13.9 ± 1.8 years; 17 (45.9%) males and 20 (54.1%) females. The hemoglobin genotypes were 1) HgbSS (n=21; 56.8%), 2) HgbSC (n=8; 21.6%), 3) HgbBeta+Thal (n=2; 5.4%) and unknown (n=6; 16.2%). Some had a history of acute chest/pneumonia (n=17; 45.9%), asthma (n=11; 29.7%), and other SCD-related complications (Table 1). More than half (n=19; 51.4%) had frequent pain crisis at home (over three pain crises at home per year), and few were severe enough to require frequent hospitalizations (n=6; 17.1% with over three hospitalizations per year due to pain). Primary care providers of these patients were in eight different medical centers in Southern California.

Table 1.

Demographics [N=37]

| Mean Age | 13.9 ± 1.8 |

| Gender | |

| Males | 17 (45.9%) |

| Females | 20 (54.1%) |

| SCD Genotype | |

| HgbSS | 21 (56.8%) |

| HgbSC | 8 (21.6%) |

| HgbBeta+Thal | 2 (5.4%) |

| Other/Unknown | 6 (16.2%) |

| Mean Grade Level | 7.4 ± 1.7 |

| History of SCD Related Illnesses** | |

| Acute Chest/Pneumonia | 17 (45.9%) |

| Asthma | 11 (29.7%) |

| Pulmonary Hypertension | 1 (2.7%) |

| Avascular Necrosis | 4 (10.8%) |

| Stroke | 5 (13.5%) |

| Splenectomy | 4 (10.8%) |

| Cholelithiasis | 1 (2.7%) |

| Splenic Sequestration | 3 (8.1%) |

| Leg Ulcers | 1 (2.7%) |

| Priapism | 3 (8.1%) |

| Iron Overload | 5 (13.5%) |

| Other | 10 (27.0%) |

| Central Line Placement | 6 (16.2%) |

| Pain Crises/Year | |

| >3 Pain Crises/year Requiring Hospitalization | 6 (16.2%) |

| >3 Pain Crises/year Not Requiring Hospitalization | 19 (51.3%) |

| 0 to 3 Pain Crisis/year | 12 (32.5%) |

Some participants had more than one and therefore, does not add to 100%

The number of text conversations and text messages within a conversation varied extensively among patients. Some messages were technical in nature such as, 1) seeking contact information about other study patients who agreed to be contacted by others, 2) notifying the APRN about technological difficulties with diary entries, or 3) asking logistical questions about the study. Patients actively engaged in numerous text conversations with the APRN. Table 2 reports general characteristics of all patients’ conversations and their frequency. The primary care activities that emerged from the text content data analysis pertained to pain and symptom management and sickle cell crisis prevention. Additionally, two primary care categories, four primary care subcategories, and 16 primary care activities were evident in text conversations (Table 3). A diagrammatic representation of the content analyses is illustrated in Figure 1, and action categories , sub-categories , and primary care activities are described in more detail below. Sample text responses to four primary care subcategories are provided in Table 4.

Table 2.

Description of Text Conversations (N=37 participants)

| Description Frequency | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Text conversations in 6 month period | 163 |

| Range of text conversations among participants | 1–14 |

| Average number of text conversations between APRN and participant | 4.4 |

| Text messages in all text conversations | 767 |

| Range of text messages in text conversations | 1–21 |

| Average number of text messages in text conversations | 4.7 |

| NP-initiated text conversations | 99 |

| Response to participant symptom reported in diary entry | 58 |

| Follow-up from previous texts about symptom / disease | 24 |

| General query about well being | 15 |

| Personal greeting (birthday) | 2 |

| Participant-initiated text conversations | 64 |

| Technological / study logistics question | 42 |

| Symptom question / update | 13 |

| Personal message / greeting / intro | 9 |

| Text conversations about symptoms / disease management | 95 |

Table 3.

Frequencies of Primary Care Activities

| Primary Care Categories and Sub-Categories | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Collaborating | 205 |

| Screening | 172 |

| Checking in (asking about participant well-being) | 32 |

| Exploring symptoms | 77 |

| Assessing symptom seriousness with participant | 36 |

| Seeking participant’s perspective on symptom meaning | 27 |

| Referring | 33 |

| Communicating with clinic / healthcare provider | 10 |

| Contacting hospital / Emergency Department | 18 |

| Suggesting technical assistance | 5 |

| Coaching | 178 |

| Informing | 86 |

| Explaining symptoms | 12 |

| Detailing symptom / health management strategies | 16 |

| Reinforcing participant decision making | 12 |

| Clarifying study logistics / operations | 46 |

| Supporting | 92 |

| Encouraging hope | 20 |

| Expressing empathy / concern | 21 |

| Sharing self | 10 |

| Connecting study participants | 16 |

| Inviting contact from participants | 25 |

Table 4.

Examples of Text Exchanges between APRN and Patients

| APRN Primary Care Action | Examples of Patient Text Responses |

|---|---|

| Screening | “I'm not feeling good since 2:45 am and my back started hurting and I have cramps and it's very painful but I don't know what to do because I don't have pain medicine.” |

| Referring | “I went to the ER. I had puss on my throat I was going to get a big symptom of strep throat if I didn’t go. They have me take a medicine…. … Thanks for the advice.” |

| “Yea I'm in the hospital … I had initially came in for my leg pain and then I got a fever and chest pain so they are treating it with antibiotics and motrin around the clock… also a PCA with dilaudid for the pain. I'm still getting fevers on and off and they treat it with motrin to break the fever. They just switched me from inhalers to breathing treatments every four hours with breakthrough treatment if necessary. I'm doing ok other than everything that's been going on. Still in some pain but the meds are helping.” | |

| Informing | I have been reading a lot about sickle cell and when I go into a crisis I talk to some of the participants of the study. I want to continue the study. Every time someone at school ask me about why my eyes are yellow? I tell them why and they get more interested into it. |

| Supporting | Thank you for checking on me. I have been here for 3 weeks and 4 days. Had 3 surgeries, 2 in one day. Almost died after my second surgery, left lung collapsed and a lot of fluid was around it, also 1 of the vessels in my heart bursted and they couldn’t stop the leaking so 15 minutes later I was rushed into third surgery for a chest tube. My blood hasn’t been staying up. I’ve already had 7 units of blood. I have 4 breathing treatments. I’m doing them now: 1. vest therapy to massage my lungs, 2. steroid inhaler, 3. breathing treatments, 4. incentive spirometor. Yeah I’m doing pretty bad, but thank you for checking on me. It means a lot. |

Collaborating

The APRN collaborated with patients in the process of screening their health concerns and colleagues in the process of referring patients for further treatment (Figure 1).

Screening

The screening action encompassed four primary care activities. The process of checking-in (Figure 1) was evident when the APRN contacted patients to follow up on symptom reports or ask about general well being. Screening was characterized by text message to patients who reported symptoms in their online diary entry that required further evaluation. Patients often responded with symptom status update. When patients did not reply to the text, the APRN followed with a phone call to further evaluate symptoms. Most often, patients responded promptly to these general queries. Occasionally, these general queries uncovered symptoms, but most often patients reported that they were doing well.

The process of exploring symptoms (Figure 1) resulted in a total of 107 symptoms that were discussed in 89 text conversations. In 77 of the 89 (86.5%) text conversations, the APRN was evaluating symptoms together with the patient to determine if home management or referral to a care provider was warranted. In the remaining 12 text conversations, the patient reported that the symptom had disappeared. The most prevalent symptom that patients described was pain (41.6%), primarily occurring in the back, chest, or extremities. Other symptoms included: not feeling well, upper respiratory congestion and cough, fever, feeling upset about something, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, vertigo, itchiness, yellow eyes, extremity swelling, painful erections, cramps, and headaches. Most patients responded with a fairly detailed description of their physical symptoms (Table 3). However, when queried about “feeling down or upset,” they commented that they did not want to text about it. Occasionally, a patient would summarize their distress, for example, as “a friend problem” or “a school problem”. Patients did not express issues related to “feeling down or upset”, via text messages, but the APRN followed up with a phone call when needed for further assessment and evaluation.

The process of assessing symptom seriousness with patient was often done coincidentally with the process of seeking patient’s perspective on symptom meaning (Figure 1). The APRN responded to pain reports by asking the patient if this episode was their serious pain or more typical pain. Patients categorized their pain symptom confidently, and if pain was serious, the APRN referred them to the hospital and often followed up with a phone call. The patient responded by describing her pain experience more extensively, her own pain management strategies, and concluded by saying, “I don’t think I have to go into the hospital because it’s not that bad”. The APRN followed with a text that included several home pain management strategies and concluded, “It will get better, but if it doesn’t, then you should go to the hospital to get extra help ☺.” Patients generally acknowledged that they understood the information before ending the text conversation. Another symptom that both patient and APRN considered serious was “fever and cough”. These symptoms were also explored collaboratively and usually resulted in the joint decision that the patient should call their healthcare provider or clinic.

Referring

The APRN was consistently alert for any indication that symptoms reported by the patient required prompt medical treatment. When the APRN referred patients to their primary healthcare provider (Figure 1), patients were willing to follow through with a call or clinic visit. However, when the APRN encouraged them to go to the hospital, emergency department or urgent care (Figure 1), she often encountered some resistance. One female patient described worsening symptoms of “sore throat” and “coughing like crazy.” The APRN asked if the patient went “to the hospital or clinic?” and the patient emphatically replied, “I don’t want to go to the hospital. I don’t want to get admitted.” The APRN text-replied, “I know you don’t want to, but … you could get worse and they can help you feel better..” The patient eventually agreed after several reiteration.

After making the referrals, the APRN sent follow-up texts or phone calls to inquire about how patients were doing, whether they were admitted, and what the healthcare provider suggested for symptom management. Some patients provided rather detailed updates (Table 4). During the study period, 11 patients were admitted to the hospital; the APRN continued text conversations with hospitalized patients to follow their progress, until they had full recovery.

Other referrals were made to the research staff for contacting technical assistance (Figure 1). Patients seemed very patient with technical difficulties and often reported quickly that difficulties were resolved.

Coaching

The APRN’s texts also evidenced many instances of guiding patients toward improved health through symptom management and health promotion. The category of coaching actions included the subcategories of informing and supporting (Figure 1).

Informing

The APRN explained symptoms (Figure 1) to patients. For example, after clarifying that a patient’s cough and sniffles were not accompanied by fever, the APRN explained, that most likely it was not a serious cold, but “coughing a lot at night and . . sniffles” suggested the possibility of seasonal allergies or asthma, and recommended that the patient see the doctor. The APRN also responded to another patient’s text question about yellow eyes and explained that it means “a lot of red blood cells breaking up in the blood system”. In one instance, a patient sent a text picture of her eye with a fluid-filled bleb. The APRN explored the circumstances, and called the patient by phone so they could talk and further evaluate. These text conversations evidenced the APRN helping young patients understand what constitutes important information for assessing risk of SCD complications.

The APRN provided detailed strategies (Figure 1) for symptom management and health promotion. When helping a patient manage pain, the APRN suggested to alternate pain medications, relax, rest and drink plenty of fluids, hot tea, warm bath, hot packs and other strategies for comfort. These instructions were frequently acknowledged by patients as helpful. When the APRN was particularly concerned about a symptom description, she reported phoning rather than texting patients with instructions. When texting management strategies, the APRN usually offered several different interventions and encouraged them to call or text an update.

The APRN sent text messages that encouraged and reinforced patient decision making (Figure 1). After asking one patient how she was handling her fatigue, the APRN sent a text that the patient is doing the right thing by trying to get as much sleep as possible. She encouraged some “exercise… to gain more energy” or if she was “too tired”, to “relax and read a book to keep mind active”. Patients usually appreciated these reminders.

The APRN also received text messages related to clarifying logistics (Figure 1). For example, in response to a question from a young patient about the daily diary, the APRN explained that answering the questions will help clinicians understand how individuals with sickle cell feel when they are at home and whether there are “signs and symptoms that may predict a pain crisis, or if some things can be done to prevent it”. Other logistical instructions included how to record symptom seriousness on the daily diary entry.

Supporting

The supporting action sub-category was prominent throughout text conversations and contained five activities. Encouraging hope (Figure 1) was exemplified by statements in response to a patient’s text updates, such as, “You’re doing all the right things, keep it up!!” and “Good! ☺ I think a transfusion will make you feel better, and the prednisone should help your lungs.” Many text conversations concluded with an encouraging comment from the APRN.

Expressions of empathizing (Figure 1) usually accompanied responses to patients’ descriptions of difficulty. For example, in response to a text that described many problems encountered by a patient during hospitalization (Table 4), the APRN sent text to say “sorry you’ve been through so much….how are you feeling today?” Sometimes, patients logged their feelings in the daily diary. The APRN often responded to those entries with text questions to further evaluate. One patient sent a text message to state that her cat died. The APRN quickly responded to inquire how she was, and if she wanted to talk about it.

Expressions of empathizing pertained not only to health problems but also to normal adolescent tribulations. One patient responded that she had a “friendship problem” and the APRN sent a text to ask if she wanted to talk about it. The APRN would call as needed. Although patients did not choose to explore their feelings openly via text, there were instances where they expressed gratitude for having someone whom they felt was available to them.

Some patients sought to personalize their texts and share self (Figure 1) with the APRN. One young patient sent an introductory text about herself accompanied by a picture of herself and mother to which the APRN replied with a warm welcome. Some patients told the APRN about their progress in school, their plans for Halloween, or their volunteer experiences at a dance marathon. Personal conversations were scattered throughout the text message exchanges. Some patients expressed enjoyment of these more personal text message exchanges with the APRN.

Another supporting activity included connecting study patients (Figure 1) to one another who agreed to be connected with other study patients similar in age. Many patients initiated text conversations with the APRN to ask for contact information. In response, the APRN provided an age-appropriate list of other patients who agreed to be contacted by other patients, and encouraged text message exchanges with each other. Some patients alluded on their contact with other patients, which was an important source of support for them. Some text messages indicated that the children and adolescents expressed how they were able to keep in touch with friends from sickle cell camp through the study, which they were not able to do previously.

The APRN provided support by inviting follow up contact (Figure 1). Whenever discussing symptoms with patients, the APRN concluded conversations with text comments such as, “Let me know if things get worse, or if you need anything else!” or “Let me know if you have pain or fevers” . In addition, the APRN consistently followed text conversations about going to the clinic or hospital with a subsequent text message that asked the patient for an update. They almost always replied with a clear description of diagnosis and treatment changes (Table 4).

The APRN’s coaching was often appreciated by patients. For example, one young study he has been “reading a lot about sickle cell” and “talking to some of the patients of the study” to seek emotional and peer social support. A patient also said that every time someone at school asked the reason why his eyes were yellow (Table 4), he told them and they were more interested about his condition. Learning more about the disease and how to manage symptoms was often acknowledged by patients as a result of text conversations that included coaching, and gratitude was consistently evident as they often thanked the APRN for her suggestions and support.

DISCUSSION

We examined the ways in which children and adolescents with SCD utilized text messaging with an APRN to control their symptoms and the subsequent primary health care activities that emerged during analyses of the content of the text message communications. We found that children were able to communicate with an APRN and were able to establish an ongoing relationship about health and SCD related matters in ways that had not been previously possible.

There were several primary health care activities that emerged from the textual data. Screening was the most prominent in text conversations, including visual inspection when one patient sent a picture of his swollen eye. As illustrated in the text message examples, patients expressed gratitude for the suggested referrals to the clinic or hospital, acknowledging that they were in fact necessary, and helpful in preventing worsening complications. There is scant information in the literature about screening, early detection, and prevention of sickle cell related complications, particularly related to pain and symptoms. Some innovative strategies have been reported to improve access to primary care services among adults with SCD (Woods, Kutlar, & Grigsby, 1998) and children with special health care needs (Karp, Grigsby, & McSwiggan-Hardin, 2000). However, our study is the first to document the possibility that screening, early detection, and prevention of complications related to pain and symptoms among children and adolescents with SCD can occur using wireless technology, specifically the smartphone. Future studies are needed to examine the effects upon outcomes and the effectiveness of this mode of interaction with health care providers. In addition, future studies should also determine whether this mode of interaction would be more successful as part of an integrated health services delivery that includes primary care providers or as a separate complementary service as implemented in our study.

We also found that patients were reluctant to enter the hospital and that sending text messages was an effective means of communicating symptom seriousness and persuading the patients to be taken by their parents to a health care provider. Results from our previous studies documented that patients had signs and symptoms associated with hospitalizations, on average four days or more prior to admission (Jacob, Beyer, Miaskowski, et al., 2005). It is unclear why children and adolescents with SCD delay seeking treatments for pain and symptoms and are reluctant to seek treatment for symptoms that may potentially lead to serious complications. Some evidence suggests that previous negative experiences (Maxwell, Streetly, & Bevan, 1999) and/or lack of awareness and knowledge regarding the consequences of delaying treatments for pain and symptoms account for delay in seeking care. Future studies are needed to examine reasons for delays in seeking treatments and test interventions that would promote health seeking behaviors. It is possible that patients may have been told to come to the emergency department only when home remedies no longer work. Negative consequences may occur as a result of delaying treatments for pain and symptoms that could have been prevented from escalating. Educational interventions are needed to include proactive and prevention strategies that would minimize delay in treatments for pain and symptoms.

Another significant finding was that text conversations were an important source for providing health information (coaching). Traditionally, parents have been the focus of education and counseling about management of their children’s disease. Parents were typically taught signs and symptoms to observe, how to avoid vaso-occlusive complications and treat pain, and when to administer prophylactic antibiotics. Consequently, as children and adolescents grow older, they often know little about signs and symptoms and rely heavily on parents to notice them. The text message conversations with the APRN allowed them to pay attention to their symptoms, and ask questions that they did not have the opportunity to do previously with care providers during clinic visits. The patients in our study were able to learn about their symptoms and understand them in such a way that they were not only able to report their own symptoms to the APRN but they also could actually explain their symptoms to peers who did not have SCD.

It was interesting to note that while text conversations about physical symptoms were prevalent, patients did not exchange communications about personal problems, even when invited by APRN. The APRN provided study contact information to those who agreed to be connected with other patients in the study. We were not able to monitor and examine text message exchange between patients, but some of them reported that it offered an important source of emotional and psychosocial support. While the use of wireless technology may be an innovative way to offer peer social support, it has a potential risk for cyberbullying, if parents are not warned to monitor use of wireless devices carefully (Betz, 2011; Kiriakidis & Kavoura, 2010; Patchin & Hinduja, 2010; Valkenburg & Peter, 2010). Although cyberbullying was not evident in text message exchanges between patients and the APRN, one parent during the study alerted the APRN and research staff about a troublesome text message received by her child. The APRN discussed this issue with both the parent and the patient who did not know the origin of the text message. Prior to enrolling in the study, patients were instructed about the restricted use of the smartphone, and agreed in writing, that the smartphone was to be used for study purposes only. Consequently, automated reminders were sent periodically to patients to remind them that the smartphone was to be used specifically for study purposes only. Exit interviews with patients did not indicate any negative consequences or any further incidents of inappropriate text messages between patients.

There were cases when several alerts about similar symptom experiences in different patients were received; the APRN would often send "bulk" text messages to patients at the same time asking things like, "I see you are having headaches (for example) today, can you tell me more about how you are feeling". Each patient would receive this "bulk" text message individually and would not see that the APRN had sent the text message to other patients. This technique was utilized by the APRN in order to be more efficient. Each patient would then respond through an individual text message, which would show up on that patient’s list of text message exchanges. However, the original bulk message sent to all of the patients did not appear in the text message exchanges. As a result, we may have underestimated the number of APRN-initiated text conversations in Table 2. We were not able to quantify the bulk text messages. It is possible that an automatic transfer of the APRN-initiated text conversations may be programmed to be automatically sent into the study server with date and time stamped to facilitate quantification in the future.

Finally, the APRN had 80% time with usual hematology clinic care activities, and 20% research related activities. The 20% research related activities included the patient-APRN interaction and communications [via text message, follow-up phone calls] that was part of the Wireless Pain Intervention, and other research related activities that includes assenting/consenting, and meetings with research staff during development of program at the beginning, and analyses/interpretation of data at the end the study. Therefore, generalizability of the findings is limited to those situations in which providers have assigned time or resources for remote monitoring of pain and symptoms and for text follow-up and patient interaction.

In conclusion, the use of wireless technology can facilitate important, interactive communications that have not been previously possible between pediatric patients and health care providers. The use of wireless devices has the potential to change and transform delivery of primary health care services for children and adolescents with SCD. Early intervention in terms of screening, early detection and prevention of pain and symptoms that could lead to SCD related complications, referral for treatments, patient education, and meaningful support are some of the ways that could improve patient care. Patients in this study were able to establish an ongoing relationship with the health care provider for matters of health and SCD in ways that had not been previously possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project described was supported by Award Number RC1HL100301 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. We thank all the children and adolescents from the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California (SCDFC) who participated in the study. We are grateful to the SCDFC and their staff, particularly Tara Ragin, who facilitated accessing patients, distribution of recruitment flyers, scheduling of patients, and making private room arrangements during the usability testing cycles. The authors wish also to acknowledge the assistance provided by Meredith Pelty, PsyD, and the University of California Los Angeles, nursing students, Miya Villanueva, Ashley Ponce, Cecilia Dong, and Anjana Gokhale for assisting with different aspects of the research. Finally, we appreciate the expertise provided by Judith E. Beyer, PhD, RN, who provided editorial suggestions on the final draft of this manuscript.

Funding was received from the National Institute of Health, National Heart Blood & Lung Institute American Recovery & Reinvestment Act Grant #1RC1 HL100301-01

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Betz CL. Cyberbullying: the virtual threat. J Pediatr Nurs. 2011;26(4):283–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles SJ, Lokker C, McKibbon KA. Health information technology to facilitate communication involving health care providers, caregivers, and pediatric participants: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(2):e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppa EC, Porter SC. A content analysis of parents' written communication of needs and expectations for emergency care of their children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(6):507–513. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31821d865e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Beyer JE, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Treadwell M, Styles L. Are there phases to the vaso-occlusive painful episode in sickle cell disease? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(4):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Stinson J, Duran J, Gupta A, Gerla M, Lewis MAL, Zeltzer L. Usability Testing of the Smartphone for Accessing a Web-Based e-Diary for Self-Monitoring of Pain and Symptoms in Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology. 2011a doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318257a13c. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran J, Jacob E, Stinson J, Lewis MAL, Zeltzer L. Innovative Technologies in Pain & Symptom Management for At-Risk Innercity Teens With Sickle Cell Disease. Paper presented at the Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Nursing; 2010, October; Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Karp WB, Grigsby RK, McSwiggan-Hardin M, Pursley-Crotteau S, Adams LN, Bell W, Stachura ME, Kanto WP. Use of telemedicine for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):843–847. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriakidis SP, Kavoura A. Cyberbullying: a review of the literature on harassment through the internet and other electronic means. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(2):82–93. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181d593e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Madden M, Hitlin P. Teens and technology: youth are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marciel K, Saiman L, Quittell L, Dawkins K, Quittner A. Cell phone intervention to improve adherence: Cystic fibrosis care team, patient and parent perspectives. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2010;45(2):157–164. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell K, Streetly A, Bevan D. Experiences of hospital care and treatment-seeking behavior for pain from sickle cell disease: qualitative study. West J Med. 1999;171(5–6):306–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Avery L. Excel as a qualitative data analysis tool. Field Methods. 2009;21(1):91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Hayes GR, Chen Y, Cygan R, Garfield CF. Improving communication between patients and providers using health information technology and other quality improvement strategies: focus on low-income children. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(5 Suppl):246S–267S. doi: 10.1177/1077558710375431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchin JW, Hinduja S. Cyberbullying and self-esteem. J Sch Health. 2010;80(12):614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccio JA, Belzer M, Olson J, Martinez M, Salata C, Tucker D, Tanaka D. The use of cell phone reminder calls for assisting HIV-infected adolescents and young adults to adhere to highly active antiretroviral therapy: A pilot study. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:438–444. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Small D, Buchan DA, Butch CA, Stewart CM, Krenzer BE, Husovsky HL. Home monitoring service improves mean arterial pressure in patients with essential hypertension. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:1024–1032. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-11-200106050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shkedi A. Multiple case narrative: A qualitative approach to studying multiple populations. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Swallow V, Newton J, Van Lottum C. How to manage and display qualitative data using ‘Framework’ and Microsoft Excel. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;32:610–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: an integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K, Kutlar A, Grigsby RK, Adams L, Stachura ME. Primary-care delivery for sickle cell patients in rural Georgia using telemedicine. Telemed J. Winter. 1998;4(4):353–361. doi: 10.1089/tmj.1.1998.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]