Abstract

The adult form of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (aADHD) has a prevalence of up to 5% and is the most severe long-term outcome of this common neurodevelopmental disorder. Family studies in clinical samples suggest an increased familial liability for aADHD compared with childhood ADHD (cADHD), whereas twin studies based on self-rated symptoms in adult population samples show moderate heritability estimates of 30–40%. However, using multiple sources of information, the heritability of clinically diagnosed aADHD and cADHD is very similar. Results of candidate gene as well as genome-wide molecular genetic studies in aADHD samples implicate some of the same genes involved in ADHD in children, although in some cases different alleles and different genes may be responsible for adult versus childhood ADHD. Linkage studies have been successful in identifying loci for aADHD and led to the identification of LPHN3 and CDH13 as novel genes associated with ADHD across the lifespan. In addition, studies of rare genetic variants have identified probable causative mutations for aADHD. Use of endophenotypes based on neuropsychology and neuroimaging, as well as next-generation genome analysis and improved statistical and bioinformatic analysis methods hold the promise of identifying additional genetic variants involved in disease etiology. Large, international collaborations have paved the way for well-powered studies. Progress in identifying aADHD risk genes may provide us with tools for the prediction of disease progression in the clinic and better treatment, and ultimately may help to prevent persistence of ADHD into adulthood.

Keywords: persistent ADHD, molecular genetics, heritability, endophenotype, IMpACT

Adult ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common, childhood onset, chronic neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate inattentiveness, increased impulsivity and hyperactivity, impairing multiple areas of life.1 ADHD has long been considered a disorder of childhood that resolves with maturation. Symptoms of inattention, impulsiveness, restlessness and emotional dysregulation in adults were considered not to reflect ADHD, but to be unspecific problems secondary to other disorders. This idea was challenged when systematic follow-up studies of children documented the persistence of ADHD into adulthood.2 Longitudinal follow-up studies of ADHD children, community surveys and epidemiological studies of population samples estimate the average prevalence of adult ADHD (aADHD) to be between 2.5 and 4.9%.3 This shows that aADHD is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in our society and clinical settings. The notion that the total number of people affected by aADHD is even larger than those suffering from ADHD during childhood and adolescence also shows that the societal consequences of this chronic debilitating condition may have been vastly underestimated in the past.4

Clinical research has shown that the predominant features of aADHD differ from typical ADHD in children (cADHD), with less obvious symptoms of hyperactivity or impulsivity and more inattentive symptoms; importantly, the frequency of psychiatric comorbidity is also increased in aADHD.5 Until recently, aADHD has been diagnosed according to clinical descriptions originally developed for children. The lack of age-appropriate clinical measures has hampered progress in this field, including genetic research. Future versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders1 may provide diagnostic measures that are better suited for all relevant age groups.

Heritability, family studies, suitability for genetic studies

Family and twin studies of cADHD demonstrate a high heritability, estimated to be around 70–80% from twin studies.6, 7 Relatively few studies have investigated the genetic and environmental contributions to the developmental course and outcomes in adulthood. Longitudinal twin studies show that the continuity of symptoms from childhood through to adolescence is predominantly due to common genetic influences.8, 9, 10 Although such stable genetic effects are likely to continue beyond the adolescent years, there are only a few studies investigating this.

Genetic research on ADHD started with the finding that hyperactivity tends to aggregate in families.11, 12 Since then, family studies have shown that ADHD shows familial clustering both within and across generations. Increased rates of ADHD among the parents and siblings of ADHD children have been observed.13, 14 In addition, strongly increased risks for ADHD (57%) among the offspring of adults with ADHD have been reported.15 Also, compared with the risk for ADHD among the siblings of children with ADHD (15%), siblings of adults with ADHD were found to have a strongly increased ADHD risk (41%).16 Furthermore, a prospective 4-year follow-up study of male children into mid-adolescence found the prevalence of ADHD to be significantly higher among the parents and siblings of persistent ADHD child probands compared with the relatives of ADHD probands in whom ADHD remitted.17 Taken together, these studies suggest that the risk for ADHD may be greater among the first-degree relatives of probands with ADHD that persists into adolescence and adulthood than that among the relatives of probands with ADHD that remits before adulthood.17, 18

Whether such familial risks reflect genetic or environmental factors can be clarified using adoption and twin studies. Adoption studies found that ADHD is transmitted only to biological relatives, which strongly implicates genetic factors as the main causal influences on familial risk for the disorder.11, 12, 19, 20, 21 These studies showed (for both current and retrospective symptoms in adults) that cADHD in child relatives predicts aADHD (or associated symptoms) in adult relatives. However, both adoption and family studies identify discrepancies related to different sources of ratings, with self-evaluation of ADHD symptoms by adults providing less evidence of familial effects than informants or cognitive performance data.19, 22, 23

Recently, four adult population twin studies using self-ratings of ADHD symptoms have been completed, which all found heritabilities that are far lower than those found in similar studies of parent- or teacher-rated cADHD: 41% for retrospectively reported childhood ADHD symptoms in a sample of 345 US veterans aged 41–58 years old,24 40% for current inattention problems in a Dutch study of 4245 18–30-year olds,8 30% for current ADHD symptoms in a Dutch study of over 12 000 twin pairs with an average age of 31 years25 and 35% for current ADHD in a Swedish sample of more than 15 000 twin pairs aged 20–46 years (Larsson et al., unpublished data). The situation is similar in adolescence, as adolescent twin studies using self-ratings show lower heritability estimates than studies of parent or teacher ratings,26, 27 suggesting that self-ratings may be a poorer measure of the underlying genetic liability to ADHD than informant reports or clinical interviews. Although the estimated heritability in self-rated ADHD symptoms in adult populations is lower than that derived from parent or teacher ratings of cADHD, the pattern of findings is identical. Both types of studies find that there are no gender differences observed in the estimates of heritability, heritability estimates are stable across the age-span (for each type of measurement approach), there are similar estimates of the genetic correlation (the proportion of shared genetic effects) of 60–70% between inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity, familial effects are all genetic in origin with no shared environmental influences, and no threshold effects are found. This suggests that for both child and adult ADHD the disorder is best perceived as the impairing extreme of a quantitative trait (Larsson et al., unpublished data; ref. 28).

Despite these common features, the relatively low heritability estimates for ADHD symptoms in adults derived from population twin studies need some explanation, because they appear to be at odds with heritability estimates of ADHD symptoms in children, as well as the family studies that show a high familial risk for persistent forms of ADHD.15, 18 Several factors are likely involved. We have already mentioned the consistent finding that self-ratings of ADHD symptoms give lower estimates of heritability compared with informant ratings in twin studies. One source of measurement error (that is, variance of the true diagnostic status that is not predicted by the measurement instrument) is the reliability of the self-rated measures of ADHD symptoms. In one of the heritability studies by Boomsma and co-workers,25 this was estimated to be around 0.66, which is lower than the mean heritability of cADHD across extant studies.29 Psychometric studies also show that, although self-ratings may be useful as a screening tool for aADHD, their correspondence with the full diagnosis is only modest. For example, Kessler et al.30 reported that the sensitivity of self-ratings as a measure of diagnosis was high (98%), whereas the specificity was not (56%). Similar findings were reported by Daigre Blanco et al.31 (87.5% sensitivity and 68.6% specificity). Related to this source of error are potential effects of having two raters in twin studies of self-ratings of ADHD (each twin rates him/herself), whereas informants usually rate both members of a twin pair. Since reliability between two raters will always be less than an individual's reliability with their own ratings, and because a ceiling on heritability is set by the reliability of ratings, heritability estimates will always be lower when two separate raters are involved in evaluating each twin pair compared with only one. Single raters may inflate identical twin pair similarities, potentially leading to an overestimation of heritability in the reported studies on cADHD, whereas the lower reliability of ratings between two raters may lead to lower estimates. Evidence for the later conclusion comes from our recent analysis of same versus different teacher ratings in a study of 5641 12-year-old twins, with heritability estimates of 75% for same teacher and 53% for different teacher ratings of twin pairs (Merwood and Asherson, unpublished data).

Another relevant difference between child and adult samples is the expected range of ADHD symptom scores. It is well known that ADHD symptoms decline through adolescence into adulthood.32 Thus, it is possible that the restricted range of ADHD symptoms in adulthood could influence estimates of heritability. Although some of this symptom decline is likely due to true remission of ADHD, some have argued that the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, which were originally developed for children, are developmentally insensitive and thus become less sensitive to ADHD with age (see above and refs. 4,33). Added to this is the possibility that in cross-sectional studies of adult population twin studies (that do not apply clinical criteria for ADHD), ADHD symptoms may emerge in some individuals owing to adult-onset conditions, such as anxiety, depression and drug use. These ‘phenocopies' would lead to increased measurement error of the genetic liability for ADHD and lower estimates of heritability.

Differences in the way that participants are ascertained in different study designs may also impact on estimates of familial/genetic influences. The family studies that showed high familial risk for ADHD used case–control methods to ascertain adult patients who were self-referred for (severe) ADHD-like problems. There are notable differences between the clinically referred and population-based samples. The former have a more skewed male-to-female ratio, higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and lower rates of primarily inattentive ADHD. Moreover, the family and twin studies used differing assessment methodologies. The family studies diagnosed subjects with structured interviews that evaluated childhood onset of impairing symptoms and the presence of impairment in multiple settings as required by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. In contrast, with the exception of Schultz et al.,34 the twin studies used rating scale measures of ADHD symptoms that do not query for childhood onset and do not systematically assess impairment in multiple settings.

Overall, these considerations suggest that the lower heritability of aADHD compared with cADHD could be due to increased measurement error in the aADHD twin studies. Support for this conclusion comes from a recent Swedish twin study, which found that the heritability of attention problems in 19–20 year olds was estimated at 78% when self-rating and parent-rating data were combined; the heritability for self-ratings alone was 48% (Larsson et al., unpublished data). Analogous to this, cluster A personality disorders show low heritability estimates in analyses based on limited phenotypic information that become much higher when adding more information from interviews.35 On the other hand, it still remains feasible that the heritability of aADHD does indeed decline with increasing age. This might reflect the importance of developmental processes that are sensitive to person-specific environmental factors affecting the longitudinal outcome of ADHD in adults.

Since heritability estimates do not relate directly to the frequency or effect size of specific genetic risk factors,36 it is not yet clear as to what the lower heritability estimates actually mean for molecular genetic studies of aADHD. For example, some disorders with low heritabilities, such as prostate and breast cancer, have identified genes with moderate to large effects,37 yet this is not the case for many highly heritable phenotypes including ADHD.38 In the absence of sufficient studies on this issue, it is quite clear that genetic researchers should preferably use measures that have been shown in family studies to have high rates of familial transmission and in adoption studies to aggregate in biological, rather than adoptive relatives. The evidence for strong familial risks in the relatives of adolescent and adult ADHD probands suggests that the clinical diagnosis of aADHD may represent a more familial measure, although there are no studies to date that directly address this question. The difference could arise because the clinical diagnosis takes a developmental perspective in which the adult phenotype reflects persistence of the childhood disorder, whereas the cross-sectional data used in twin studies may include adult-onset causes of ADHD-like symptoms that reflect phenocopies involving different etiological processes.

We conclude that aADHD is influenced by familial factors that are genetic in origin. The available studies indicate that self-ratings of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition-defined ADHD symptoms may not be the best measure of the underlying genetic risk for aADHD and that other factors such as childhood onset, pervasiveness and impairment should be taken into account.

Molecular genetic studies

Candidate gene association studies in adult ADHD

A search of NCBI's PubMed database for genetic association studies revealed 46 publications on aADHD (published until June 2011). Most of these studies are based on clinically assessed patients. The majority of studies examined single (or a few) polymorphisms in dopaminergic and serotonergic genes focusing predominantly on the dopamine transporter (SLC6A3/DAT1) and the dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4), both associated with cADHD in meta-analysis39 (Table 1).40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83

Table 1. Genetic association studies directed at identifying risk factors for adult ADHD or influencing adult ADHD severitya (studies in adolescents were not included in the selection).

| Name of gene | Gene symbol | Polymorphism investigated | Type of analysis | Sample investigated | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic genes | ||||||

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR | ANOVA, qualitative and quantitative FBAT | 152 cases; 102 families (72 overlapping with case study; 45 triads, 36 pairs, 16 multiple sib families, 5 multigeneration families) | No association | Muglia et al.40 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR | Case–control | 122 hyperactive, 67 controls, followed to adulthood | 9/10 genotype more symptoms (P=0.01) and more impairment (work performance (P=0.02), grade point average (P=0.04)) than 10/10 genotype, more omission errors on a continuous performance test | Barkley et al.41 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR; 30 bp VNTR in intron 8 | Case–control | 122 cases, 174 controls | No association of single VNTRs or haplotype | Bruggemann et al.42 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR | Case–control | 358 cases, 340 controls | No association | Johansson et al.43 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR; 30 bp VNTR in intron 8 | Case–control | 216 cases, 528 controls | Association of 9-6 haplotype with ADHD diagnosis (P=0.0011) | Franke et al.44 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR; 30 bp VNTR in intron 8 | Case–control/meta-analysis | 1440 cases, 1769 controls | Association of 9-6 haplotype with ADHD diagnosis (P=0.03), association of 9/9 genotype with ADHD diagnosis (P=0.03) | Franke et al.45 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR | Case–control | 102 cases, 479 controls | No association | da Silva et al.46 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | SLC6A3/DAT1 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR | Case–control | 53 cases, 38 controls | Association of 9-repeat (9R) allele carriership with ADHD diagnosis (P=0.004), marginal association of 9R with working memory-related brain activity | Brown et al.47 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter; dopamine receptor D4 | SLC6A3/DAT1, DRD4 | 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR of SLC6A3/DAT1, 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 of DRD4 | Cox proportional hazard models | ADHD cases and family members (n=563) | By 25 years of age, 76% of subjects with a DRD4 7-repeat allele were estimated to have significantly more persistent ADHD compared with 66% of subjects without the risk allele. No effect of DAT1 | Biederman et al.48 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter; dopamine β-hydroxylase; dopamine receptor D4; dopamine receptor D5 | SLC6A3/DAT1, DBH, DRD4, DRD5 | SLC6A3/DAT1 40 bp VNTR in 3′-UTR; DBH TaqI SNP in intron 5 (rs2519152); DRD4 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 and 120 bp VNTR in promoter; DRD5 (CA)n repeat 18.5 kb from the start codon of gene | Regression analysis, taking life events and personality factors into account | 110 cases | No effects of genes on ADHD severity | Müller et al.49 |

| Dopamine receptor D4; solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3=dopamine transporter | DRD4, SCL6A3/DAT1 | DRD4 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 and 120 bp ins/del in promoter; SLC6A3/DAT1 40 bp VNTR in 3′ UTR and 30 bp VNTR in intron 8 | Case–control/meta-analysis | 1608 cases, 2358 controls | Nominal association (P=0.02) of the L-4R haplotype (dup120–48 bp VNTR) with aADHD, especially with the combined clinical subtype. No interaction with DAT1 haplotype | Sanchez-Mora et al.50 |

| Dopamine receptor D4 | DRD4 | 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 | Case–control, TDT, combination | 66 cases, 66 controls; 44 families (29 triads, 14 pairs); combination of all cases (n=110) | Evidence for association in case–control (P=0.01) and combined sample (P=0.003) (7R vs non-7R alleles) | Muglia et al.51 |

| Dopamine receptor D4 | DRD4 | 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 and 120 bp ins/del in promoter | Association/linkage (PDT) | 14 multigeneration families from genetic isolate (Colombia), children and adults affected | 7R allele of 48 bp VNTR (P=0.0578), haplotype of 7R-240 bp allele overtransmitted (P=0.0467) | Arcos-Burgos et al.52 |

| Dopamine receptor D4 | DRD4 | 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 | Model fitting on Temperament/Character Inventory (TCI) and DRD4 genotype | 171 subjects from 96 families (=parents of ADHD sib pairs; 33% with lifetime ADHD, 15% with current ADHD) | DRD4 correlates with ADHD symptoms (r2=0.05), but not with novelty seeking (7R vs non-7R genotypes) | Lynn et al.53 |

| Dopamine receptor D4 | DRD4 | 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 | Case–control | 122 hyperactive, 67 controls, followed to adulthood | No association | Barkley et al.41 |

| Dopamine receptor D4 | DRD4 | 48 bp VNTR in exon 3 | Case–control | 358 cases, 340 controls | No association | Johansson et al.43 |

| Dopamine receptor D3 | DRD3 | rs6280 (Ser9Gly) | TDT | 39 families (25 triads, 14 pairs) | No association | Muglia et al.54 |

| Dopamine receptor D3 | DRD3 | rs2399504, rs7611535, rs1394016, rs6280 (Ser9Gly), rs167770, rs2134655, rs2087017 | Regression analysis | 60 binge eating disorder cases, 60 obese and 60 non-obese controls assessed for adult ADHD symptoms | Haplotypes containing the Ser9 allele higher hyperactive/impulsivity scores compared with those containing Gly9 for a haplotype window containing rs1394016 and Ser9Gly (global P=0.00038), as well as that containing Ser9Gly and rs167770 (global P=0.00017) | Davis et al.55 |

| Dopamine receptor D2 | DRD2 | rs1800497 (TaqIA C>T) | Case–control | 85 alcoholics, 32.9% diagnosed with ADHD | No association | Kim et al.56 |

| Dopamine receptor D2 | DRD2 | rs1800497 (TaqIA C>T) | ANOVA, comparison between patients with autism (ASD) and ADHD, with and without substance use disorders | 49 ADHD cases, 61 ASD patients | No association | Sizoo et al.57 |

| Dopamine receptor D5 | DRD5 | (CA)n repeat 18.5 kb from the start codon of gene | TDT, case–control | 119 families with adult ADHD probands; 88 cases, 88 controls | Nonsignificant trend for association between the 148 bp allele and ADHD (P=0.055); excess of non-transmissions was detected for the 150 bp (P=0.023) and 152 bp (P=0.028) alleles; quantitative analyses for 150 bp allele with lower scores (lowest P=0.008) | Squassina et al.58 |

| Dopamine receptor D5 | DRD5 | (CA)n repeat 18.5 kb from the start codon of gene | Case–control | 358 cases, 340 controls | Nominally significant association with adult ADHD (P=0.04), trend toward increased risk for 148 bp allele; strongest association with combined and inattentive subtypes (P=0.02; OR=1.27) | Johansson et al.43 |

| Dopamine β-hydroxylase | DBH | TaqI SNP in intron 5 (rs2519152) | TDT, case–control | 97 triads; 112 cases, matched controls | Borderline significance in case–control comparison (P=0.057), risk allele under-represented in cases | Inkster et al.59 |

| Dopamine β-hydroxylase | DBH | TaqI SNP in intron 5 (rs2519152) | Case–control | 122 hyperactive children, 67 controls, followed to adulthood | Adult A2 allele homozygotes take more risk in Card playing task (P=0.021) | Barkley et al.41 |

| Dopamine β-hydroxylase | DBH | rs1611115 (−1021C>T) | Case–control, regression analysis | Four independent samples: healthy volunteers (n=387), patients with affective disorders (n=182), adult (ADHD cases (n=407), patients with personality disorders (n=637) | No association with ADHD (or other psychiatric diagnoses); association with neuroticism in ADHD, and conscientiousness in combined analysis of ADHD+personality disorder samples | Hess et al.60 |

| Catechol O-methyl transferase | COMT | rs4680 (Val158Met) | Regression analysis | 203 healthy subjects assessed with ASRS for adult ADHD symptoms | Association of Val with inattention (P=0.008), hyperactivity/impulsivity (P=0.039) and total ASRS scale (P=0.006), highest scores Met/Met | Reuter et al.69 |

| Catechol O-methyl transferase | COMT | rs4680 (Val158Met) | Case–control | 85 alcoholics, 32.9% diagnosed with ADHD | No association | Kim et al.56 |

| Catechol O-methyl transferase | COMT | rs4680 (Val158Met) | Regression analysis | 110 cases | No association | Müller et al.61 |

| Catechol O-methyl transferase | COMT | rs4680 (Val158Met), rs4818 | Regression analysis | 184 men referred for psychiatric examination, frequency of adult ADHD unclear | No association with ADHD, no gene–environment interaction with psychosocial adversity in childhood; nominal association with ADHD scores of combination of two haplotypes of SLC6A4 and COMT | Retz et al.62 |

| Catechol O-methyl transferase | COMT | rs6269, rs4633, rs4818, rs4680 (Val158Met) | Regression analysis | 435 cases, 383 controls | Trend for association with hyperactivity/impulsivity scores for all markers, peaking at marker rs6269 (P=0.007); haplotype analysis showed association of suggested high COMT-activity haplotype with highest hyperactivity/impulsivity score (P=0.01) | Halleland et al.63 |

| Serotonergic genes | ||||||

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Case–control | 30 (of 314) alcoholics with ADHD+anti-social personality disorder vs alcoholics without comorbidity vs matched controls | No association | Johann et al.64 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Case–control | 312 cases, 236 controls | No association with ADHD; nominal association with higher inattention and novelty-seeking scores, and a higher frequency of drug dependence | Grevet et al.65 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Case–control | 85 alcoholics, 32.9% diagnosed with ADHD | No association | Kim et al.56 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Regression analysis | 184 men referred for psychiatric examination, frequency of adult ADHD unclear | L/L genotype associated with persistent ADHD (P=0.047); gene–environment interaction: carriers of at least one S allele are more sensitive to childhood environment adversity than carriers of L/L (P=0.025) | Retz et al.62 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR; rs25531 in LPR | Regression analysis | 110 cases | Taking into account stressors, the L allele showed association with increased ADHD severity, particularly as regard affective dysregulations (P=0.002); in subjects exposed to early stressors, the L allele showed a protective effect compared with the S allele (P=0.003) | Müller et al.61 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR and seven tag-SNPs in discovery sample; 5-HTTLPR and one SNP in meta-analysis | Case–control | 448 patients and 580 controls in discovery sample, 1894 patients and 1977 controls in meta-analysis | Association with rs140700 (P=0.00084, in women) and S allele of the 5-HTTLPR (P=0.06) in discovery; only S allele associated with adult ADHD at P=0.06 in replication. Potential findings for rare variants | Landaas et al.66 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Regression analysis, gene–environment interaction | 123 cases with adult ADHD (and 183 patients suffering from personality disorders) | No association with adult ADHD, no G × E effects | Jacob et al.67 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter | SLC6A4/5-HTT | 5-HTTLPR | Cox proportional hazard models | ADHD cases and family members (n=563) | No effect of 5-HTT | Biederman et al.48 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter; tryptophan hydroxylase 2 | SLC6A4/5-HTT, TPH2 | 5-HTTLPR in SLC6A4/5-HTT, rs1843809 in TPH2 | ANOVA, comparison between patients with autism (ASD) and ADHD, with and without substance use disorders | 49 ADHD cases, 61 ASD patients | Carriership of G-allele of TPH2 rs1843809 and of L-allele of the 5-HTTLPR was less frequent in ADHD compared with ASD patients (P=0.041 and 0.04, respectively) | Sizoo et al.57 |

| Serotonin receptors 1A, 1B, 1D, 1E, 1F, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 4, 5A, 6, 7; solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 4=serotonin transporter; tryptophan hydroxylase 1; dopa decarboxylase; monoamine oxidase A, B | HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR1D, HTR1E, HTR1F, HTR2A, HTR2B, HTR2C, HTR3A, HTR3B, HTR4, HTR5A, HTR6, HTR7, SLC6A4/5-HTT, TPH1, DDC, MAOA, MAOB | 132 tag-SNPs | Case–control | 188 adult cases (+263 children), 400 controls | DDC: associated with adult (lowest P=00053, OR 2.17) and childhood ADHD; MAOB: associated with adult ADHD (lowest P=0.0029, OR 1.9); HTR2A: association with combined subtype in adults (lowest P=0.0036, OR 1.63) and children | Ribases et al.68 |

| Serotonin receptor 2A | HTR2C | Cys23Ser | Case–control | 30 (of 314) alcoholics with ADHD+anti-social personality disorder vs alcoholics without comorbidity vs matched controls | No association | Johann et al.64 |

| Serotonin receptor 2A | HTR2A | 102T>C | Regression analysis | 203 healthy subjects assessed with ASRS for adult ADHD symptoms | Association of C allele with hyperactivity/impulsivity (P=0.020) and total ASRS scale (P=0.042), highest scores in T/T genotype | Reuter et al.69 |

| Serotonin receptor 2A | HTR2A | rs6314 (His452Tyr) | Regression analysis, taking life events and personality factors into account | 110 cases | No effects of genes on ADHD severity | Müller et al.49 |

| Serotonin receptor 1A | HTR1A | rs6295 | Regression analysis, gene–environment interaction | 123 cases with adult ADHD (and 183 patients suffering from personality disorders) | Decrease the risk of anxious–fearful cluster C personality disorders in adult ADHD (P=0.016) | Jacob et al.67 |

| Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 | TPH2 | rs4570625 | Regression analysis, gene–environment interaction | 123 cases with adult ADHD (and 183 patients suffering from personality disorders) | No association with adult ADHD, no G × E effects | Jacob et al.67 |

| Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 | TPH2 | 18 SNPs in discovery sample, 5 SNPs in meta-analysis | Regression analysis; meta-analysis | 1636 cases, 1923 controls in meta-analysis | TPH1: nominal association for rs17794760; TPH2: no association | Johansson et al.70 |

| Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | TPH1 | 9 SNPs in discovery sample, 1 SNP (rs17794760) in meta-analysis | ||||

| Noradrenergic genes | ||||||

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 2=norepinephrine transporter | SLC6A2/NET1 | rs998424 (intron 9) | ANOVA, qualitative and quantitative FBAT | 128 triads | No association | De Luca et al.71 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 2=norepinephrine transporter | SLC6A2/NET1 | rs5569, rs998424, rs2242447 | Regression analysis | 184 men referred for psychiatric examination, frequency of adult ADHD unclear | No association with ADHD, no gene–environment interaction with psychosocial adversity in childhood; nominal association with ADHD scores of combination of two haplotypes of SLC6A4 and COMT | Retz et al.62 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 2=norepinephrine transporter | SLC6A2/NET1 | rs998424 (intron 9) | Regression analysis | 110 cases | No association | Müller et al.61 |

| Adrenergic α-2A-receptor | ADRA2A | rs1800544, rs1800544, rs553668 | Case–control | 403 cases, 232 controls | No association | de Cerqueira et al.72 |

| Adrenergic α-2C-receptor | ADRA2C | (TG)n 15 kb upstream of start codon | TDT | 128 triads | No association (TG16 and TG17 alleles) | De Luca et al.71 |

| Neurotrophic genes | ||||||

| Nerve growth factor; brain-derived neurotrophic factor; neurotrophin 3; neurotrophin 4/5; ciliary neurotrophic factor; neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, types 1, 2, 3; nerve growth factor receptor; ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor | NGF, BDNF, NTF3, NTF4/5, CNTF, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, NGFR, CNTFR | 183 tag-SNPs | Case–control | 216 adults (330 children), 546 controls | Single-marker and haplotype-based association of CNTFR and both adulthood (lowest P=0.0077, OR=1.38) and childhood ADHD | Ribases et al.89 |

| Neurotrophin 3; neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, types 2, 3; brain-derived neurotrophic factor; nerve growth factor receptor | NTF3, NTRK2, NTRK3, BDNF, NGFR | NTF3 rs6332 and rs4930767, NTRK2 rs1212171, NTRK3 rs1017412, BDNF rs6265 (Val66Met), p75(NTR) rs2072446 | Regression analysis | 143 men referred for psychiatric examination, frequency of adult ADHD unclear | Exonic NTF3 variant (rs6332) showed nominal trend toward association with increased scores of retrospective childhood analysis Wender–Utah Rating Scale (WURS-k) (P=0.05) and adult ADHD assessment Wender–Reimherr interview (P=0.03) | Conner et al.74 |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | BDNF | rs6265 (Val66Met) | Case–control/meta-analysis, regression analysis | 1445 cases, 2247 controls | No association | Sanchez-Mora et al.75 |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | BDNF | rs6265, rs4923463, rs2049045, rs7103411 | Regression analysis, taking life events and personality factors into account | 110 cases | No effects of genes on ADHD severity | Müller et al.49 |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; lin-7 homolog A | BDNF, LIN-7 | rs4923463, rs6265 (Val66Met), rs11030104, rs2049045 and rs7103411 in BDNF; rs10835188 and rs3763965 in LIN-7 | TDT, case–control | 80 trios of adult ADHD proband and parents; 121 cases, 121 controls | BDNF Val66Met, BDNF rs11030104, LIN-7 rs10835188 associated with ADHD in combined analysis | Lanktree et al.76 |

| Others | ||||||

| Protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, type I | PRKG1 | 2276C>T | TDT | 63 informative nuclear families | No association | De Luca et al.77 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α7; protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, type I; trace amine-associated receptor 9 | CHRNA7, PRKG1, TAAR9 | CHRNA7 D15S1360; PRKG1 2276C>T; TAAR9 181A>T | Regression analysis, taking life events and personality factors into account | 110 cases | No effects of genes on ADHD severity | Müller et al.49 |

| Clock homolog | CLOCK | rs1801260, 3′-UTR | Regression analysis | 143 men referred for psychiatric examination, frequency of adult ADHD unclear | Association of genotypes with at least one T allele with self-reported and interview ADHD scores (lowest P=0.00002) | Kissling et al.78 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 family (mitochondrial) | ALDH2 | SNP, identity unclear | Case–control | 85 alcoholics, 32.9% diagnosed with ADHD | No association | Kim et al.56 |

| Cannabinoid receptor 1 | CNR1 | 4 tag-SNPs | Relevant for adult ADHD: case–control | Unselected adolescent sample and family-based sample of trios (ADHD child plus parents). Trio parents (with and without ADHD) used as additional case–control sample of adults (n=320; 46% affected) | Association with childhood ADHD, but no association with adult ADHD | Lu et al.79 |

| Nitric oxide synthase 1 | NOS1 | Ex1f VNTR | Case–control | Personality disorder cases (n=403), adult ADHD (n=383), familial ADHD (n=151), suicide attempters (n=189), criminal offenders (n=182), controls (n=1954) | Short variant more frequent in adult ADHD (P=0.002), cluster B personality disorder (P=0.01), autoaggressive (P=0.02)/heteroaggressive (P=0.04) behavior | Reif et al.80 |

| Latrophilin 3 | LPHN3 | Different sets, rs6551665, rs1947274 and rs2345039 were investigated in the largest sample | Case–control | 2627 (childhood and adult) ADHD cases and 2531 controls | rs6551665 (P=0.000346), rs1947274 (P=0.000541) and rs2345039 (P=0.000897) were significant after correction for multiple testing | Arcos-Burgos et al.81 |

| Latrophilin 3 | LPHN3 | 44 SNPs tagging the gene | Case–control | 334 cases, 334 controls | rs6858066: P=0.0019, OR=1.82 (1.25-2.70); three-marker haplotype (rs1868790/rs6813183/rs12503398): P=5.1e-05, OR=2.25 (1.52–3.34) for association with combined ADHD | Ribases et al.82 |

| BAI1-associated protein 2; dapper, antagonist of β-catenin, homolog 1; LIM domain only 4; neurogenic differentiation 6; ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, plasma membrane 3; inhibitor of DNA binding 2, dominant negative helix–loop– helix protein | BAIAP2, DAPPER1, LMO4, NEUROD6, ATP2B3, ID2 | 30 tag-SNPs | Case–control | Exploration sample: 270 adults (317 children), 587 controls; replication samples: 639 adult ADHD cases, 612 controls and 417 adult ADHD cases, 469 controls | Single- and multiple-marker analysis showed association of BAIAP2 with adult ADHD (P=0.0026 and 0.0016, respectively); replication in the larger one of the two replication samples (P=0.0062) | Ribases et al.73 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L-type, α 1C subunit; ankyrin 3, node of Ranvier (ankyrin G); myosin VB; tetraspanin 8; zinc-finger protein 804A | CACNA1C, ANK3, MYO5B, TSPAN8 and ZNF804A | ZNF804A rs1344706, ANK3 rs9804190 and rs10994336, CACNA1C rs1006737, TSPAN8 rs1705236, MYO5B rs4939921 | Regression analysis | 561 ADHD cases, 711 controls | No association | Landaas et al.83 |

| Contactin-associated protein-like 2; cadherin 13 | CNTNAP2, CDH13 | rs7794745 in CNTNAP2, rs6565113 in CDH13 | ANOVA, comparison between patients with autism (ASD) and ADHD, with and without substance use disorders | 49 ADHD cases, 61 ASD patients | Carriership of T-allele of the CNTNAP2 rs7794745 polymorphism more often present in the ADHD group compared with the ASD group (P=0.025) | Sizoo et al.57 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; aADHD, adult form of ADHD; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ASRS, Adult Self-Report Scale; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; CNTFR, ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor; DAT1, dopamine transporter gene; DRD4, dopamine receptor D4; FBAT, family-based association test; 5-HTTLPR, serotonin transporter; MAOB, monoamine oxidase B; OR, odds ratio; PDT, pedigree disequilibrium test; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TDT, transmission disequilibrium test; TPH2, tryptophan hydroxylase 2; VNTR, variable number of tandem repeats; 3′-UTR, 3′-untranslated region.

Individual studies may appear in the list several times.

In all, 10 studies looked at the 40-bp variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the SLC6A3/DAT1 gene, or a haplotype of this and a second 30-bp VNTR in intron 8. Although most studies found no evidence of association with aADHD,40, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49 three studies41, 44, 47 found a consistent association with the 9-repeat allele or the 9-6 haplotype rather than the 10/10 genotype or the 10-6 haplotype associated with cADHD.84, 85 This association of the 9-6 haplotype and the 9/9 genotype with aADHD was confirmed by a meta-analysis of 1440 cases and 1769 controls,45 which makes it the most robust finding for adult ADHD, to date. Why the association in adults is different from the one found in children is not entirely clear. A number of explanation are possible, for example, (a) that the 9-repeat allele and the 9-6 haplotype may mark a severe subgroup of ADHD patients prone to disease persistence, (b) SLC6A3 may modulate rather than cause ADHD, and (c) that the 9-repeat allele and 9-6 haplotype only become aberrant in an adult brain with its lower dopamine levels.45 For DRD4, most studies predominantly focused on a functional tandem repeat polymorphism in exon 3 of DRD4, in which one variant (the 7-repeat allele) is associated with cADHD.39 Of six studies from five independent samples, three were negative,41, 43, 49 whereas the three others showed nominal evidence that the 7-repeat allele increased risk for aADHD.51, 52, 53 A recent study of the long-term outcome of cADHD suggested that carriers of the 7-repeat allele show a more persistent outcome of ADHD.48 While being reasonably powered, this latter result seems at odds with an earlier finding showing a normalization of the cortical thickness in ADHD-relevant brain regions linked to a better clinical outcome during adolescence in carriers of the DRD4 7-repeat allele.86 A large meta-analysis in 1608 aADHD patient and 2358 control samples was negative for the 7-repeat allele, although showing nominal evidence for association of a haplotype formed by the common 4-repeat allele of the exon 3 VNTR and the long (L) allele of the 120-bp insertion/deletion upstream of DRD4.50 Findings for DRD4 are the most consistent ones for cADHD,39 but more research is clearly needed to understand its role in aADHD. Among studies on other dopamine receptor genes (DRD2, DRD3 and DRD5), the findings for a DRD5 VNTR have been most positive. Although individually unconvincing, the findings of two of three studies point in the same direction, indicating that the same allele associated with cADHD might also increase risk for aADHD.43, 58 Of the genes involved in dopamine turnover, COMT and DBH, the two largest studies (investigating functional COMT variants) showed association with aADHD. However, the direction of association in each of the studies was opposite.63, 69

Among the serotonergic genes, the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4/5-HTT/SERT) and its functional polymorphism, 5-HTTLPR, were studied most often,48, 56, 57, 61, 64, 65, 66, 67, 87 with essentially negative or conflicting results, even in a large meta-analysis of 1894 patients and 1977 controls.70 One study used a tagging approach and investigated a total of 19 serotonergic genes68 and reported association of aADHD with single markers or haplotypes in MAOB, DDC and HTR2A. The latter gene was also found associated with aADHD in one of two additional studies, although the polymorphism involved was different.49, 69 A recent, large study in 1636 patients and 1923 controls investigated the two TPH genes and found nominal evidence of association with TPH1, but not TPH2.70

Three genes in the noradrenergic system, the noradrenalin transporter (SLC6A2/NET), ADRA2A and ADRA2C, have been tested for association with aADHD. As shown in Table 1, however, there has been no evidence of association for these genes with aADHD.61, 62, 71, 72, 88

Two studies have looked at several genes encoding neurotrophic factors: Ribasés et al.89 used a full tagging approach and showed association with aADHD for CNTFR, but did not replicate earlier research, suggesting an association with NTF3.74 There have been five studies of the BDNF functional Val66Met polymorphism,49, 74, 76, 90 including a meta-analysis of 1445 cases and 2247 controls,75 that found no evidence for association.

A number of novel candidate genes have been associated with aADHD in isolated studies and are in need of independent replication. Of particular interest may be LPHN3, which was selected for study from fine mapping of a significant linkage region on chromosome 4q13.81 LPHN3 was associated with ADHD in a large sample of children and adults,81 and subsequently replicated in an independent aADHD sample.82 The function of this gene, which encodes a G-protein-coupled receptor, is still not well understood.91 BAIAP2 was found to be associated with aADHD in a study investigating six genes with lateralized expression in the developing brain;73 as brain asymmetry is altered in ADHD,92 this interesting finding might point to etiological pathways for ADHD not involving neurotransmitter signaling. In addition, following up the findings for the circadian rhythm gene CLOCK may be fruitful,78 as a dysregulated circadian rhythm is a consistent finding in both cADHD and aADHD.93 A fourth gene, NOS1, associated with aADHD80 should be considered in future studies, as evidence for an involvement of this gene in ADHD also comes from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) in cADHD.38

Linkage analysis

So far, no linkage studies have been performed looking only at aADHD patients, but two included adults with ADHD and one reported on ADHD symptoms in the population. In the former two, multigenerational pedigrees were investigated. One of them investigated 16 pedigrees from a Colombian Paisa genetic isolate, including a total of 375 individuals (126 cases).94 Fine mapping of regions of suggestive linkage allowed identification of several regions with significant evidence of linkage and a family-specific significant logarithm of odds score on chromosome 8q11.23. Although most of the findings indicated novel ADHD susceptibility loci, regions on 8q11 and 17p11 overlapped with suggestive linkage findings on cADHD.95, 96, 97 In a second study of eight pedigrees (154 family members, 95 cases), several significant linkage regions were found in a combined analysis of all families.98 In addition, family-specific significant findings were also present, some of which (on chromosomes 1, 7, 9, 12, 14 and 16) overlapped with regions earlier implicated in cADHD.96, 97, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 The study on adult ADHD symptoms in the population investigated sibling pairs (approximately 750) and their family members. Linkage was observed on chromosomes 18q21 and 2p25, and suggestive evidence for aADHD loci was present on chromosomes 3p24 and 8p23.106 Meta-analysis of linkage results derived from seven of nine independent studies (mostly on cADHD) was performed in 2008.107 This analysis revealed one region of significant linkage, on the distal part of chromosome 16q, which contains the CDH13 gene, found nominally associated by GWAS in both cADHD and aADHD (see below), and nine loci with nominal or suggestive evidence of linkage.

Genome-wide association studies

While linkage analysis is mainly suited for the identification of loci having moderate to large effects,108 GWAS can identify common variants increasing the disease risk with only small effects. So far, only one has been performed in aADHD. Although not providing genome-wide significance findings, this DNA pooling-based 500K SNP scan109 identified several potential risk genes and revealed remarkable overlap with findings from GWAS in substance-use disorders. By comparing GWAS results with results from the previously reported high-resolution linkage scan in extended pedigrees,98 several loci harboring ADHD risk genes could be confirmed, including the 16q23.1–24.3 locus containing CDH13. The findings provide support for a common effect of genes coding for cell adhesion/pathfinding molecules (for example, CDH13), regulators of synaptic plasticity (for example, catenin alpha 2 (CTNNA2)) and ion channels or related proteins (for example, voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel α 1D subunit (CACNA1D) and dipeptidyl-peptidase 6 (DPP6)). These pathways show strong overlap with the findings from GWASs in cADHD (for a review see ref. 38).

New developments and initiatives

It appears that the genetic factors underlying ADHD (as well as other psychiatric disorders) are of even smaller effect size than anticipated,110 or are not well covered by current study designs. This has inspired researchers to improve their study designs and to come up with alternative research approaches. The most relevant of these developments for the study of adult ADHD are reviewed below.

Improvement in study designs

If effect sizes of individual genetic factors are small, increasing sample size in genetic studies should substantially improve power for gene finding. This realization has led to an increase in the collaborations between research groups. For aADHD specifically, the International Multicentre persistent ADHD CollaboraTion (IMpACT) was formed in 2007. Including researchers from Europe, the United States and Brazil, this consortium coordinates genetic material of over 3500 well-characterized aADHD cases and approximately 4000 controls. IMpACT has performed meta-analyses of several known candidate genes for ADHD45, 66, 70, 75 (Table 1), thereby providing evidence for differences in the genetic predisposition to persistent ADHD compared with cADHD.

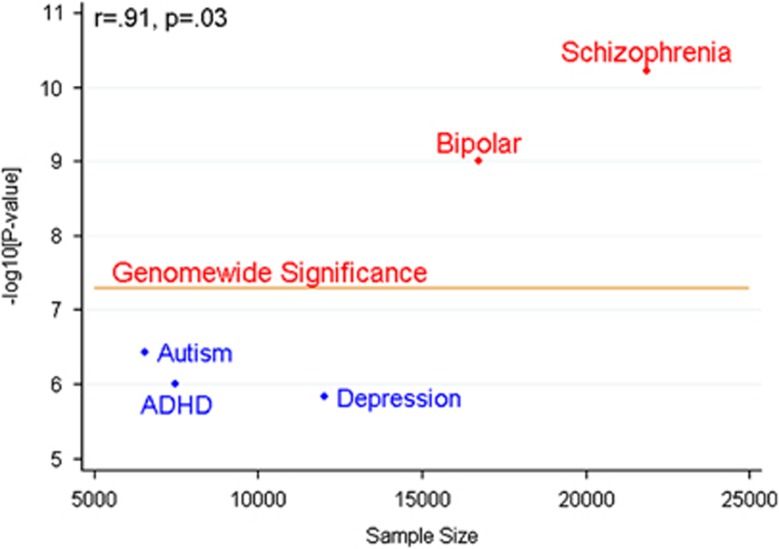

Other examples for collaborative efforts in genetics are the ADHD Molecular Genetics Network,111 a well-established worldwide network of researchers working on ADHD genetics, and the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium (PGC).112 The PGC provides a forum for sharing genome-wide genotyping data and phenotypic information for studies on ADHD (but also on autism spectrum disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, see below) (http://www.pgc.unc.edu/index.php).113 Recently, a meta-analysis of ADHD GWASs in the PGC database was performed, including 2064 child–parent trios, 896 cases and 2455 controls.110 This did not yield genome-wide significant findings, yet, potentially due to small effect sizes of individual variants, disease heterogeneity and gene–environment interactions (for a more extensive review of potential reasons for the ‘missing heritability', see ref. 114). The absence of genome-wide significant findings in a meta-analysis of the current size is not unexpected: a comparison with data on the other disorders within PGC shows a strong correlation between minimal P-values and sample size (Figure 1), suggesting that genome-wide significant findings can only be expected at sample sizes of more than 12 000 individuals (cases and controls combined). These data clearly emphasize the need for multisite collaborations between researchers in ADHD genetics.

Figure 1.

Plotted is the sample size (cases+controls) analyzed in the first meta-analyses of the Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, autistic spectrum disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) against the −log of the minimal association P-value observed in the GWAS. The P-value indicating genome-wide significance of findings is indicated. The data show the strong (r=0.91) and significant (P=0.03) correlation between the two parameters. Drawing a line through the points suggests that at least 12 000 samples (cases+controls) will be needed before genome-wide significant findings for ADHD will be observed.

In such multisite studies of ADHD, one problem is the potential disease heterogeneity among sites due to genetic or cultural differences. However, in this regard it is reassuring that the presentation of ADHD and its prevalence is similar across different countries. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of epidemiological studies show that there are no differences in the prevalence of ADHD between European countries or between Europe and the United States.115, 116 Similarly, as we reviewed elsewhere,6, 29 the heritability of ADHD does not vary with geographic location. Although these similarities in prevalence and heritability between countries do not assure disease homogeneity, they are consistent with the idea of substantial homogeneity between countries. Furthermore, a large body of literature suggests cross-cultural stability of the ADHD phenotype. Cross-cultural diagnostic studies find no cross-cultural differences in prevalence or expression, when methods of diagnosis are systematized across sites.117 Factor analysis studies have shown that the covariation of ADHD symptoms is invariant across many cultures,118, 119, 120, 121 and cross-cultural studies have also shown considerable stability in the psychiatric and neuropsychological correlates of ADHD.117, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126 In addition to these findings, which were based on the binary diagnosis of ADHD, studies that have used quantitative measures of ADHD show cross-cultural stability in both clinical comorbidity and developmental trends.127, 128, 129, 130 These findings are so compelling that a systematic review of ADHD cross-cultural issues concluded that ‘taken together, these findings suggest that ADHD is not a cultural construct'.131 It is still possible that different sites in a multisite study identify clinically different types of ADHD due to differences in ascertainment (for example, from the population versus clinical samples), exclusion criteria (for example, excluding comorbid disorders) or methodology (for example, the use of different structured diagnostic interviews). The best approach to this problem would be to require sites to use similar methods of ascertainment and assessment.

As mentioned above, the PGC not only brings together data sets for disease-specific GWAS meta-analyses, but also stimulates cross-disorder analyses. This is inspired by the high degree of overlap that has been noted in findings from phenotypic dimensional and molecular genetic studies (for example, refs. 38,132,133); especially, autism and bipolar disorder have a high degree of comorbidity with ADHD, which seems to be caused—at least in part—by overlapping genetic factors.134, 135, 136, 137 Findings from disease-specific GWAS also show association across diagnoses, like the findings that the bipolar risk gene diagylglycerol kinase H (DGKH) is also associated with adult ADHD,138 whereas the ADHD risk gene DIRAS family, GTP-binding RAS-like 2 (DIRAS2), vice versa, is also associated with bipolar disorder.139 Such candidate studies exemplify how common variants might influence disorders on the dimensional, syndromic level—for example, emotional dysregulation—while not being associated with a specific disorder per se. Although this seems plausible for common genetic variants, intuitively one would say that rare variants should be more specific for certain diseases. However, previous examples from studies of rare variants in ADHD, namely copy number variants (CNVs), show an enrichment of CNVs at sites linked to autism and schizophrenia140 (IMAGE II Consortium, under review). Classical approaches relying on traditional nosology fall short to explain such data. As the edge of dawn of more biologically orientated diagnostic systems might be near, the large-scale cross-disorder studies might be one step to elucidate functional genetic networks underlying psychiatric dysfunctioning.

Studies on endophenotype and intermediate phenotypes

Intermediate phenotypes are traits that mediate the association between clinical phenotypes and genes.141, 142 Following the recently suggested terminology from Kendler and Neale,143 endophenotypes reflect measures of brain function that are genetically correlated with a clinical disorder or trait (that is, they share genetic risk factors), whereas the term intermediate phenotype should be reserved for measures that mediate the association between genes and clinical phenotypes. To be considered an endophenotype, a trait must meet several requirements, which include heritability, co-segregation with disease in families, association with disease in the population and higher trait scores in unaffected siblings of patients compared with controls, as well as a criterion relating to the measurement having to be highly accurate and reliable.144 The endophenotypes identified according to these criteria are variables that index genetic risk for disorders, such as ADHD, and include mediating pathways (intermediate phenotypes) as well as pleiotropic phenotypes that reflect multiple different effects of genes. To identify an intermediate phenotype among the endophenotypes requires the additional step of demonstrating mediation between genes and disorder, which can only be tested once one or more genetic markers are found that show association to both the clinical disorder and the endophenotype.135, 143 An example relevant to the study of ADHD is the finding that social cognition mediates the association between the COMT gene and antisocial behavior in cADHD, whereas measures of executive function that were also associated with COMT were found to reflect pleiotropic (multiple outcomes of genes) rather than mediating effects.145

Compared with categorical diagnoses such as ADHD, endophenotypes are assumed to be more proximal to genes in biological pathways (whether they represent intermediate or pleiotropic effects) and to be genetically less complex and giving rise to greater effect sizes of genetic variants. This makes endophenotypes better suited for genetic studies than clinical phenotypes.36, 38 Both endophenotypes and intermediate phenotypes may be used to map genes associated with ADHD, but only intermediate phenotypes can be used to identify the processes that are involved directly in the etiology of ADHD.

Several neurocognitive traits may serve as candidate intermediate phenotypes, because the core features of ADHD (inattention and hyperactivity) are conceptually related with cognitive domains such as executive function, attention, arousal, memory and intelligence.146, 147, 148 Most research in this area has focused on children.149 A meta-analysis of 83 studies involving executive functions (EFs) in cADHD consistently identified deficits on group measures of response inhibition, vigilance, working memory and planning, but noted moderate effect sizes and lack of universality.150 Indeed, (c)ADHD shows considerable heterogeneity with regard to any single cognitive deficit.147 For example, nearly 80% of children with ADHD have a deficit on at least one measure of executive function, but this can also be said of around half of control subjects.151 Temporal processing (response variability),152, 153 visuospatial and verbal working memory,152, 154 response inhibition as measured by the stop-signal reaction time task and interference control149, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158 seem to fulfill the basic criteria for endophenotypes of ADHD and may represent mediating processes. Recently, multivariate analysis of a large cADHD proband, sibling and control sample identified two main familial cognitive factors. The larger factor, which reflected 85% of the familial variance of ADHD, captured all familial influences on response times and response time variability, whereas a second smaller factor reflecting 12.5% of the familial effects on ADHD captured influences on omission errors and commission errors on a go/no-go task.159 These findings may be particularly relevant to aADHD because they reflect two separate developmental processes indexing arousal and attention processes that are hypothesized to underlie persistence and remission of ADHD during the transition into adulthood.160, 161

In aADHD, a range of neurocognitive deficits has also been reported, including problems in sustained attention,162, 163, 164, 165 verbal fluency,166 set shifting,162, 165, 166 word reading,167 color naming,167 verbal and visual working memory,167, 168 interference control165, 169 and response inhibition.163, 166, 170, 171, 172, 173 A meta-analysis of 33 studies concluded that neurocognitive deficits in adults with ADHD are found across a range of domains, in particular involving attention, behavioral inhibition and working memory, with normal performance for simple reaction times.174 Which of these measures satisfy the formal criteria for endophenotypes and intermediate phenotypes of aADHD has yet to be fully investigated.

Despite these promising findings, few neuropsychological phenotypes have yet been used in molecular genetic studies of ADHD, let alone aADHD. There is currently no robust evidence for association between candidate intermediate phenotypes and ADHD candidate genes.175 For aADHD, only two neuropsychological endophenotype studies have been published. Barkley and co-workers41 found association between the 3′-UTR VNTR of the SLC6A3/DAT1 and making more omission errors on a continuous performance test, and the DBH TaqI A2 allele-homozygous participants took more risks in a card playing game. The DRD4 exon 3 VNTR did not have any effects (Table 1). A pilot study in 45 adults with ADHD compared the performance of carriers and non-carriers of ADHD risk alleles in DRD4 (exon 3 VNTR, 120 bp promoter insertion/deletion), SLC6A3/DAT1 (3′-UTR VNTR) and COMT (Val158Met) on a large battery of neurocognitive tests. The study showed COMT to be related to differences in IQ and reaction time, an association of DRD4 with verbal memory skills, and linked SLC6A3/DAT1 to differences in inhibition.176 Two linkage studies reported suggestive loci for traits derived from several neuropsychological tasks.177, 178 With one important prerequisite for endophenotypes suitable for use in genetic studies being measurement errors smaller than those of the related clinical phenotype, single neurocognitive tests may not be the most suitable targets for genetic testing, as they can be prone to several sources of measurement error due to fluctuations in mental state and motivation, stress, fatigue or time of the day.143 A potentially better situation is provided by the use of aggregated measures across neuropsychological tasks in the same way that aggregation of tests is used to estimate IQ. Studies showing the general feasibility of such an approach for gene finding have been performed in children with ADHD (see above; ref. 159).

Structural and functional neuroimaging measures, including both magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive electrophysiology, may be even better suited as endophenotypes, as they generally show strong test–retest reliability in adolescents and adults.179, 180, 181, 182 Two recent meta-analyses suggest that genetic effect sizes at the level of brain activity may be considerable.183, 184 There is ample evidence for dysfunction and subtle structural brain anomalies in ADHD. Most studies have focused on functional aspects of dysfunction reporting deficits in the domains of verbal working memory,185, 186, 187, 188 response inhibition,189, 190 error monitoring191, 192, 193 as well as reward processing and delay aversion.194, 195 Again, only a few studies in aADHD have been published, and there are almost no findings that can be considered replicated (see for a review ref. 196). Studies vary largely by imaging method (functional magnetic resonance imaging or event-related potentials) and paradigm, and almost every research group uses slightly different versions of a given task. In structural imaging, brain volumetry studies in aADHD patients reported reductions of brain volume in the prefrontal cortex196, 197 and anterior cingulate cortex,198 caudate nucleus199, 200 and amygdala,201 as well as a marginal increase of nucleus accumbens volume.196 Only some of these findings have been replicated, to date.200, 202 Interesting recent findings also show structural and functional brain connectivity to be disturbed in ADHD.203, 204

Few studies yet have reported effects of ADHD candidate genes on imaging phenotypes in aADHD. By means of event-related potentials elicited by a go/no-go paradigm and subsequent topographical analysis, it was shown that TPH2 risk alleles previously linked to ADHD205 were associated with reduced no-go anteriorization (suggested to reflect prefrontal brain activity) in aADHD patients as well as healthy controls.206 Likewise, the 9-repeat allele of the SLC6A3/DAT1 3′-UTR VNTR (associated with aADHD45) resulted in a reduction of the no-go anteriorization,207 whereas homozygosity for the 10-repeat allele (which is linked to a higher expression of the transporter in striatum, at least in healthy adults using SPECT208, 209) was associated with hypoactivation in the left dorsal anterior cingulate cortex compared with 9-repeat allele carriership in aADHD patients,210 and a stronger working memory task-related suppression in left medial prefrontal cortex was found in 9-repeat allele carriers compared with 10/10 homozygotes.47 The ADHD risk haplotype of LPHN3 was found associated with no-go anteriorization,211 and was also shown by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy to decrease the N-acetylaspartate to creatine ratio in the left lateral and medial thalamus and the right striatum, regions altered volumetrically and/or functionally in ADHD.81 Also, the NOS1 exon 1f VNTR showed reduced no-go anteriorization in the controls of a study of impulse-disorder patients (including aADHD patients) homozygous for the short allele of the VNTR, the ADHD risk genotype.212 More recently, an investigation of this variant showed both homozygous short allele aADHD patients and healthy controls to display higher ventral striatal activity during reward anticipation than subjects with the other genotypes.213 A study investigating electroencephalogram measures found an effect of the DRD4 7-repeat allele on the power in the electroencephalogram beta band.214 Furthermore, subjects with this allele were found to have a significantly smaller mean volume in the superior frontal cortex and cerebellum cortex compared with subjects without this allele.215

Based on the above, endophenotypes may be very promising tools for the characterization of biological pathways from gene to disease on the one hand and for gene finding in ADHD on the other. However, as discussed, one should not automatically assume a simple mediational relationship between an endophenotype and a clinical phenotype. Reality may be much more complex. Endophenotypes may be risk indicators of the occurrence or the severity of the clinical phenotype, without exerting a causal influence, genetic influences are expected to be only partially shared between endophenotype and clinical phenotype, and even where mediation is demonstrated, the influences between intermediate phenotype and clinical phenotype could be bi-directional.135, 143 This all complicates the use of endophenotypes in a straightforward way to identify genes for ADHD. Moreover, as has been shown in research of autism, similar genetic variants may influence a very broad range of endophenotypes, suggesting that the effective distance between variations in the sequence or structure of the DNA and resulting brain endophenotypes may be still quite large.216 Nonetheless, using endophenotypes continues to be a powerful way to unravel the genetic architecture of multifactorial disorders such as aADHD, but its effective application may require moving to more comprehensive approaches that include the simultaneous modeling of multiple endophenotypes, innovative statistical methods and the combination of those with bioinformatics.217 Assessing endophenotypes in multisite collaborative studies would additionally require prospective studies using identical measures across sites, or the definition of derived (aggregate) measures that capture the underlying trait optimally while reducing task-specific measurement noise (for example, ref. 159).

New methods for the statistical analysis of genetic association

Hypothesis-driven candidate gene studies have been the focus of many research groups, as, with current sample sizes, they provide superior power. However, instead of investigating single polymorphisms, entire genes or even entire functional networks are currently being investigated. The first examples of these studies have focused on the association of neurotrophic factors,90, 74 the serotonergic system68 and brain laterality-related genes73 with aADHD (see Table 1). Tools like the KEGG Pathway Database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html), Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org) or DAVID (http://www.david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) are useful for identifying possible candidate systems and selecting the constituent genes. This approach may also be applied to the analysis of data from genome-wide genotyping efforts, by calculating association scores between the disorder and functional groups. An example of a statistical approach for this was recently published for the analysis of IQ in a sample of children with ADHD,218 but similar univariate as well as multivariate approaches have been suggested.219, 220, 221, 222

With the improvement of statistical methods, the investigation of gene-by-environment (G × E) and gene-by-gene (G × G) interactions is becoming more and more feasible. So far, only very few studies have addressed this issue in aADHD (Table1 and above), in largely underpowered studies. In cADHD, more literature is available, but results for individual genes are still conflicting.223, 224, 225

Bioinformatic analyses are becoming more and more important as a tool for the integration of genetic findings. Such analyses can indicate biological processes and pathways enriched in the data from GWASs.226 In ADHD, a study on copy number variants (see below) showed enrichment for genes important for learning, behavior, synaptic transmission and central nervous system development227 using bioinformatics. Another recent study integrated the top-ranked findings of all published GWAS in ADHD and found a strong enrichment of genes related to neurite outgrowth.228

Investigation of rare genetic causes of ADHD and alternative patterns of genetic transmission

Judging from the high prevalence of ADHD in the general population and the strong decline of disease risk from first- to second-degree relatives, a multifactorial polygenic inheritance model has been considered most likely for ADHD.229, 230With the involvement of environmental factors, the disorder seems best described as being of multifactorial origin. The multifactorial polygenic model has motivated the search for common DNA variants, as described above, using candidate gene, genome-wide linkage and GWAS. However, given the limited success of GWAS in ADHD, thus far,110, 231 in conjunction with reports on increased burden of rare copy number variants in, for example, schizophrenia and autism (for example, refs. 232,233), ADHD researchers have begun the search for rare variants that might account for some of ADHD's heritability.

From case reports, we have known for a long time that unique mutations can lead to ADHD. Examples include a translocation involving the solute carrier family 9 member 9 gene, SLC9A9,234 and an inactivating mutation in TPH2,235 both found to co-segregate with ADHD in two different families, but also larger chromosomal abnormalities.236, 237, 238, 239, 240, 241 In addition, several syndromes caused by rare genetic mutations (including the 22q11 deletion syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome) are known to show increased incidence of ADHD(-like phenotypes),242, 243 although adult forms of ADHD are often not part of the clinical assessment of these patients.

Most of the earlier studies have not systematically investigated the entire genome for rare, deleterious mutations, nor did they indicate whether such mutations also cause ADHD in adults. A first systematic analysis of microdeletions and duplications (CNVs), including adults with ADHD, has been published recently.244 This study revealed de novo as well as inherited CNVs associated with ADHD. A particularly interesting finding from this study includes an extended pedigree with multiple cases of ADHD and obesity, in which a duplication of the gene encoding neuropeptide Y (NPY) was observed. From this, in conjunction with a number of studies systematically investigating CNVs in data from GWASs of cADHD (published,227, 245, 246 or currently under review), it becomes clear that some ADHD cases—rather than being caused by multiple common variants—may be caused by rare genetic variants with relatively large effect sizes. What fraction of ADHD cases can be explained by such oligogenic (or perhaps even monogenic) causes, however, will have to await studies involving genome-wide sequencing,247, 248 as microdeletions and duplications are likely to be not the only type of genetic variant involved. The study of extended pedigrees with multiple affected members might provide a shortcut to finding some of the altered genes. Intriguingly, a recent publication also suggests that some associations found in GWAS studies—seemingly caused by common variants—might actually be based on synthetic association with rare variants in partial linkage disequilibrium with the common variants.249

In addition to considering rare versus common genetic variants, alternative patterns of genetic transmission should be considered. Based on studies of rare coding variants affecting the function of TPH1, a strong maternal transmission of the risk allele was suggested.250 Parent of origin effects have also been suggested for common variants in cADHD.251, 252 Similar specific patterns of genetic transmission could occur for many candidate genes, but the effects would easily be obscured in case–control studies.

Clinical impact of understanding the genetics of adult ADHD

Compared with other clinical neurosciences, little progress has been made in the application of molecular diagnostics to the common psychiatric disorders. Notably, genetic tests are now commonly being used in the diagnosis of early-onset neurodegenerative disorders. Although Parkinson's disease has traditionally been considered a non-genetic disease, during the past 15 years many rare Mendelian and common low-risk loci for this disease have been successfully identified. Taken together, these loci account for about half of the accumulated risk of developing early-onset Parkinson's disease and genetic testing of these markers has rapidly become useful for diagnosis and for defining new therapeutic strategies.253 In analogy with such examples, it may be possible to identify susceptibility genes in subgroups of patients with monogenic or oligogenic forms of aADHD by sequencing and genotyping pedigrees with a high load of this disorder. Genotyping of such rare, highly penetrant genetic variants may have clinical utility where aADHD needs to be differentiated from progressive neurological conditions or other somatic or psychiatric disorders. Although our current understanding of the genetic models of transmission and the variants involved is still limited, with increasing knowledge of these variants, and in the hands of experts in psychiatric genetics, this might become feasible in the future. However, as the susceptibility genes that have been robustly identified in GWASs of psychiatric disorders so far seem to confer vulnerability across a range of psychiatric phenotypes and the genetic markers have very low predictive value,38, 133, 254, 255 it is expected that such a clinical application of aADHD genetics will only appear gradually.

Another way of incorporating the results of genetic research into clinical practice is pharmacogenetics, the individualization of treatment strategies based on the association of DNA variants with drug efficacy or adverse events. Pharmacogenetic testing may be able to help clinicians in individualizing the treatment option for any ADHD patient, in terms of efficacy and tolerability.256, 257 In all, 30% of aADHD patients do not respond favorably to stimulant treatment (methylphenidate or amphetamines) and 40% exhibit non-response to atomoxetine. In addition, many patients present side effects with these drugs, like an increase in arterial tension or insomnia, that can cause them to drop out of treatment.258 However, efforts at understanding the putative role of candidate genes in the response to pharmacotherapy for ADHD have been inconclusive,259 a pharmacogenetic GWAS found no genome-wide significant associations,260 and—with the exception of a few studies261, 262, 263—the pertinent literature is exclusively focused on pediatric samples and on a few genes.

Prediction of outcome and prevention of persistence through intervention is a particularly relevant clinical issue. Knowing that ADHD remits in a percentage of cases,2 and that both genetic and environmental factors are involved in its etiology provides a basis for hypothesizing that ADHD persistence into adulthood might be preventable in some patients by intervention early in childhood. Indeed, the finding from longitudinal twin studies of ADHD throughout child and adolescent development suggest a role for newly developing genetic influences at different developmental states,9, 264 but further twin studies are needed that span from adolescence through into adulthood. The literature on the prognostic value of individual genetic factors is still contradictory. In this regard, ADHD children carrying the DRD4 7-repeat allele show normalization of the cortical thinning in the right parietal cortical region, a pattern that linked with better clinical outcome.86 In contrast, others showed that in ADHD patients reassessed after 5 years, carriers of the DRD4 7-repeat allele showed less decline in severity than those without the risk allele.265 Other findings indicate that DRD4 7-repeat allele carriers are more persistently affected than those not carrying this risk allele,48 and no effect of DRD4 was observed in another study.41 A meta-analysis of SLC6A3/DAT1 by IMpACT suggests that a different haplotype from that reported associated with cADHD is associated with aADHD,44, 45 see above. In line with this, carriers of the 9/10 genotype of the 3′-UTR VNTR were earlier shown to have a worse prognosis than those with the 10/10 genotype.41 Additional genetic analyses in large longitudinal studies will be needed to investigate (patterns of) genetic variants of potential value.

Looking forward

In this paper, we critically reviewed current literature on the genetics of aADHD, the most severe form of the disorder. So far, this is still limited, as most work has been concentrated on the disorder in children.

The extent of heritability of ADHD in adults has not been firmly established, and stringently characterized samples should be used to provide more exact estimates.

Adult ADHD etiology is likely to involve both common and rare genetic variants. Although the search for common DNA variants predisposing for ADHD has not yet successfully achieved the level of genome-wide significance, recently reported genome-wide significant effects for other psychiatric disorders (for example, ref. 266) suggest that similar findings for ADHD will be forthcoming. Given that the effects of common genetic variants are expected to be very small, their relevance to ADHD cannot be ruled out in currently available samples. Therefore, more genome-wide studies of common as well as rare variants are absolutely necessary. In addition, we should strive for improvements in the statistical tools used to perform such studies as well as those enabling integration of the findings.