Abstract

We performed bottom-up engineering of a synthetic pathway in E. coli for the production of eukaryotic trimannosyl chitobiose glycans and the transfer of these glycans to specific asparagine residues in target proteins. Glycan biosynthesis was enabled by four eukaryotic glycosyltransferases, including the yeast uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine transferases Alg13 and Alg14 and the mannosyltransferases Alg1 and Alg2. By including the bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase PglB from C. jejuni, glycans were successfully transferred to eukaryotic proteins.

N-linked protein glycosylation is the most common post-translational modification in eukaryotes, affecting many important protein properties1. N-linked glycosylation is not limited to eukaryotes, however, as bona fide N-linked glycosylation pathways are found in proteobacteria2 and can be transferred to E. coli3. There are several notable differences between bacterial and eukaryotic N-glycosylation systems. First, bacteria assemble oligosaccharides on undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (Und-PP) in the cytoplasmic membrane whereas eukaryotes use dolichyl pyrophosphate (Dol-PP) in the ER membrane. Second, the N-X-S/T consensus sequence for N-glycosylation in eukaryotes appears to be extended to D/E-X−1-N-X+1-S/T (X−1, X+1 ≠ P) in bacteria4 with few exceptions5,6. Third, bacterial N-glycans are completely distinct from any known eukaryotic glycan7. As a result, glycoproteins derived from existing bacterial expression systems are restricted to bioconjugate vaccines8,9 or glycoproteins that require extensive in vitro modification10. The construction of a eukaryotic glycosylation pathway in E. coli that generates human-like N-glycans remains an elusive challenge despite much speculation7,11.

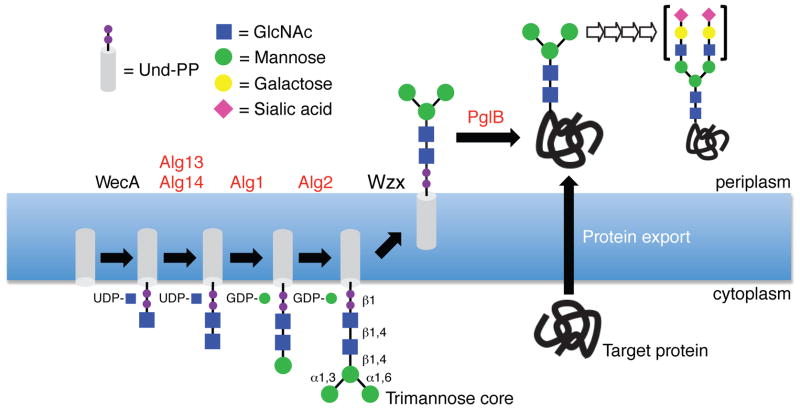

To address this challenge, we focused on engineering E. coli to produce mannose3-N-acetylglucosamine2 (Man3GlcNAc2) glycans. We chose Man3GlcNAc2 because it is: (i) the core structure common to all human N-glycans; (ii) the predominant N-glycan produced by baculovirus-insect cells, carrot root plant cells, and Tetrahymena thermophila, all of which yield glycans that are fit for pre-clinical and clinical products; and (iii) the minimal glycan required for a therapeutic glycoprotein currently on the market12. To generate Man3GlcNAc2 on the cytoplasmic membrane of E. coli, a synthetic pathway was designed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Engineering eukaryotic glycan biosynthesis in E. coli.

Schematic of the synthetic pathway for synthesis of a trimannosyl core glycan and transfer to acceptor sites in target proteins. Enzyme names in black are native to E. coli; enzyme names in red are heterologous. See text for details. Glycan in brackets to the right of open arrows depicts terminally sialylated structure common in human glycoproteins, but outside the scope of this study.

The first step in this pathway involved WecA, an endogenous glycosyltransferase (GTase) that transfers GlcNAc-1-phosphate to undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P). To extend the glycan, several heterologous GTases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were selected because these can be solubly expressed in E. coli13–15 and in some cases the expressed enzymes are active in vitro13,14. Specifically, for addition of the second GlcNAc residue to GlcNAc-PP-Und, we chose the S. cerevisiae β1,4-GlcNAc transferase that is comprised of the Alg13 and Alg14 subunits. In yeast, Alg14 is an integral membrane protein that functions as a membrane anchor to recruit soluble Alg13 to the cytosolic face of the ER membrane15, where synthesis of GlcNAc2-PP-Dol occurs. Consistent with their localization in yeast, both Alg13 and Alg14 localized in the membrane fraction of E. coli while Alg13 was also detected in the soluble fraction (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the subsequent steps, we employed S. cerevisiae β1,4-mannosyltransferase Alg1, which specifies the addition of the first mannose to the glycan14, and the bifunctional mannosyltransferase Alg2, which carries out the addition of both an α1,3- and α1,6-mannose in a branched configuration13. Like Alg13/14, both Alg1 and Alg2 localized in the membrane fraction of E. coli (Supplementary Fig. 1).

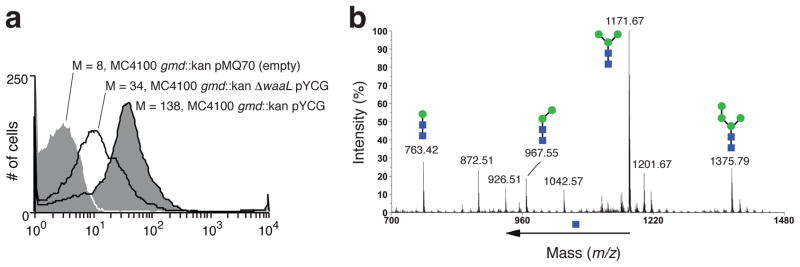

To determine if enzyme co-expression was capable of producing a functional Man3GlcNAc2 biosynthesis pathway, we constructed plasmid pYCG that encoded a synthetic gene cluster comprised of ALG13, ALG14, ALG1 and ALG2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). To increase the availability of the GDP-mannose substrate for Alg1 and Alg2, GDP-mannose dehydratase (GMD) that converts GDP-mannose to GDP-4-keto-6-deoxymannose in the first step of GDP-L-fucose synthesis was deleted from E. coli strain MC4100. To assay glycan synthesis, we exploited the fact that bacterial cell surfaces can display engineered oligosaccharides in their lipopolysaccharide layer16,17. This approach depends upon the O-antigen ligase WaaL, which catalyzes the transfer of Und-PP-linked oligosaccharides to lipid A. These oligosaccharides are shuttled to the cell surface where they can be conveniently labeled16,17. Upon labeling with fluorescent concanavalin A (ConA), a lectin that binds terminal α-mannose, MC4100 gmd::kan cells expressing the synthetic pathway but not empty-vector control cells became highly fluorescent (Fig. 2a). The fluorescence was clearly localized on the cell surface (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In the absence of ALG1 or ALG2, cell fluorescence was significantly diminished (Supplementary Fig. 3b) confirming that these enzymes were required for producing surface-associated α-mannose residues. Likewise, when the synthetic pathway was expressed in MC4100 gmd::kan that also lacked waaL, cells were minimally fluorescent (Fig. 2a) confirming WaaL-dependent transfer of α-mannose-containing oligosaccharides to lipid A. Importantly, a native E. coli flippase (e.g., Wzx) must be involved since WaaL uses Und-PP-linked oligosaccharides that are present on the periplasmic face of the cytoplasmic membrane18.

Figure 2. Characterization of LLOs produced by glycoengineered E. coli.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of E. coli MC4100 gmd::kan or MC4100 gmd::kan ΔwaaL cells carrying plasmids as indicated. Cells were labeled with ConA-AlexaFluor prior to flow cytometry. Median cell fluorescence (M) values are given for each histogram. (b) MALDI-MS profile of permethylated glycans released from LLOs by acid hydrolysis. LLOs were extracted from E. coli MC4100 gmd::kan carrying plasmid pYCG. The major signal at m/z 1171 corresponds to [M+Na]+ of Hex3HexNAc2.

To verify the glyan structure, lipid-linked oligosaccharides (LLOs) were extracted and characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) analysis. The MALDI-MS spectrum revealed Hex3HexNAc2 as the primary oligosaccharide, consistent with the expected Man3GlcNAc2 glycan. In addition, Hex2HexNAc2 and Hex4HexNAc2 were detected (Fig. 2b). The MALDI-MS spectrum of LLOs isolated from MC4100 gmd::kan ΔwaaL cells also revealed Hex3HexNAc2 as the primary oligosaccharide (Supplementary Fig. 4). This confirmed that the lack of cell surface labeling observed for these cells was a result of the waaL deletion and not the inability to synthesize oligosaccharides. Finally, released glycans analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy were consistent with the eukaryotic core glycan Manα1–3(Manα1–6)-Manβ1–4-GlcNAcβ1–4-GlcNAc (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). NMR analysis also revealed a residue with H-1 (5.080 ppm) and H-2 (4.065 ppm) chemical shifts indicating that the fourth hexose residue was likely Man linked to one of the branching Man residues (Supplementary Fig. 5). The presence of a putative Man4GlcNAc2 was surprising because elongation of Man3GlcNAc2 is attributed to the bifunctional Alg1113. It should be noted, however, that both Man3GlcNAc2-PP-Dol and Man4GlcNAc2-PP-Dol accumulated in a S. cerevisiae ALG11 mutant19, suggesting that Alg1 or Alg2 may catalyze Man4GlcNAc2-PP-Dol production in vivo.

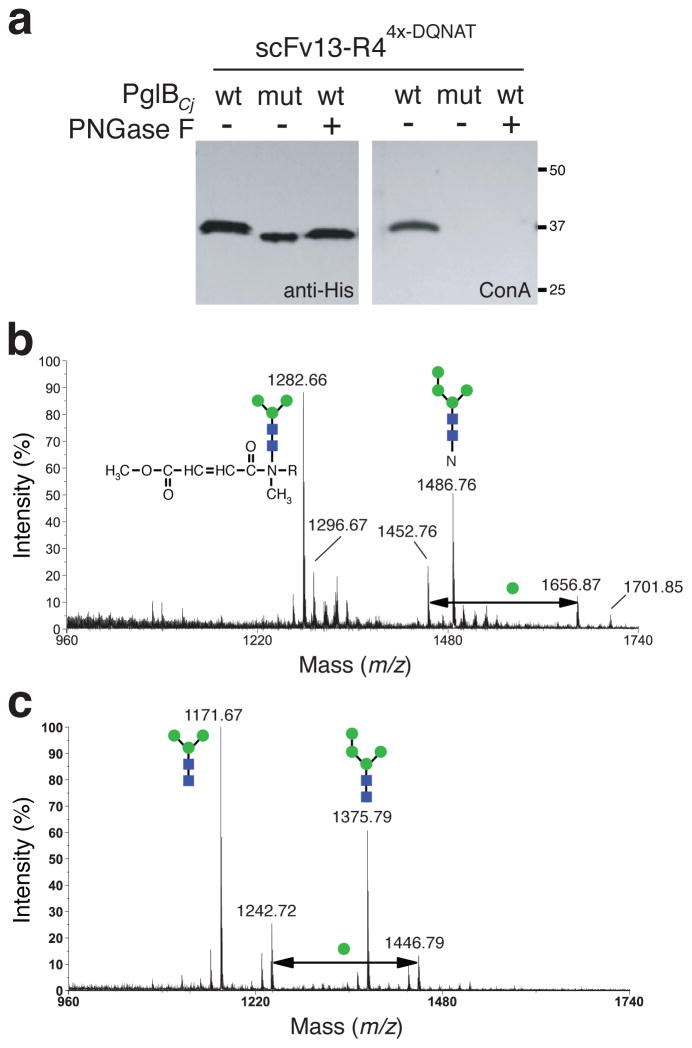

To transfer Man3GlcNAc2 glycans to secretory glycoproteins in vivo, we focused our attention on PglB from C. jejuni (PglBCj) because it is the best characterized bacterial OTase20 and can utilize diverse Und-PP-linked oligosaccharides as substrates2,3,8,9. For glycoprotein targets, we chose (i) E. coli maltose binding protein (MBP) which is a native periplasmic protein and (ii) anti-β-galactosidase single-chain antibody fragment called scFv13-R4 that was modified with an N-terminal co-translational export signal from E. coli DsbA17. These proteins were each modified C-terminally with four tandem repeats of the bacterial glycan acceptor motif DQNAT17. MC4100 gmd::kan ΔwaaL cells were transformed with plasmids encoding one of these target proteins and the Man3GlcNAc2 pathway with PglBCj (Supplementary Fig. 2). The MBP4x-DQNAT and scFv13-R44x-DQNAT produced in these cells, but not in cells carrying an inactive PglBCj mutant3, was bound by ConA (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 8). When these target proteins were first treated with peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGase F), an amidase that specifically cleaves between a reducing-end GlcNAc and asparagine, ConA binding was eliminated (Fig. 3a). To further confirm that glycans were linked specifically to asparagines in target proteins, a version of scFv13-R4 with a single C-terminal DQNAT sequon was digested with Pronase E and the resulting glycopeptides were identified using MS21. The major ion seen at m/z 1282 was consistent with Man3GlcNAc2-Asn, wherein the asparagine residue underwent β-elimination during the permethylation procedure (Fig. 3b)21. MS analysis of the PNGase F-released glycans from glycosylated scFv13-R44x-DQNAT revealed Hex3HexNAc2 as the predominant glycoform along with a lesser amount of Hex4HexNAc2 (Fig. 3c). MS2 sequencing of the glycan at m/z 1171 confirmed the biantennary trihexosyl structure (Supplementary Fig. 9a). When PNGase F-released glycans were treated with α-exomannosidase to specifically hydrolyze terminal α-mannose residues, HexHexNAc2 emerged as the major glycoform at the expense of both Hex3HexNAc2 and Hex4HexNAc2 (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Finally, 1H NMR analysis on PNGase F-released glycans was consistent with Manα1–3(Manα1–6)-Manβ1–4-GlcNAcβ1–4-GlcNAc (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11).

Figure 3. Transfer of eukaryotic glycans to target proteins in E. coli.

(a) Western blot analysis of scFv13-R44x-DQNAT affinity purified from E. coli MC4100 gmd::kan ΔwaaL cells carrying pYCG-PglBCj or pYCG-PglBCjmut as indicated. Proteins isolated from cells expressing wild-type PglBCj were further treated with PNGase F for removal of N-linked glycans. Polyhistidine tags on the proteins were detected using anti-His antibodies while mannose glycans on the proteins were detected using ConA. See Supplementary Fig. 8 for full, uncut gel image. (b) MALDI-MS profile of permethylated glycopeptides generated by digestion of scFv13-R41x-DQNAT with Pronase E. The major signal at m/z 1282 corresponds to the permethylation product of Hex3HexNAc2-N, where the asparagine residue underwent β-elimination during the permethylation procedure (see inset). (c) MALDI-MS profile of permethylated glycans released from scFv13-R44x-DQNAT by PNGase F treatment. The major signal at m/z 1171 corresponds to [M+Na]+ of Hex3HexNAc2.

We next attempted to transfer Man3GlcNAc2 to eukaryotic glycoproteins including: (i) the Fc domain of human IgG1 at its conserved N297 glycosylation site, (ii) bovine ribonuclease A (RNaseA) at its N34 acceptor site, and (iii) the placental variant of human growth hormone (hGHv) at its N140 glycosylation site. The genes encoding these proteins were cloned downstream of an N-terminal DsbA export signal or full-length MBP in the case of hGHv. Since the N-X-S/T consensus motif in eukaryotes is extended to D/E-X−1-N-X+1-S/T in bacteria4, we mutated the native glycosylation motifs in the Fc (QYNST, residues 295–299) and hGHv (IFNQS, residues 138–142) to DQNAT. Likewise, we used an RNaseA variant with an S32D substitution22. Expression of these target proteins in cells carrying the pYCG-PglBCj plasmid yielded clearly glycosylated proteins (Supplementary Fig. 12a and b). It should be noted that RNaseA glycosylation was unexpected because the acceptor site is located in a structured domain that is not glycosylated by PglBCj in vitro22 Hence, our data indicate that PglBCj can glycosylate residues in both unstructured and structured regions of eukaryotic acceptor proteins in vivo.

Since it does not have native glycosylation pathways, our engineered E. coli strain is the only platform for glycoprotein expression that offers bottom-up synthesis of precise glycan structures by expression of diverse GTases and OTases. Despite our success, however, there remain some important challenges that need to be overcome for the practical application of this technology. For example, an acidic group at the -2 position to the asparagine seems to be a common prerequisite of PglB homologs for efficient glycosylation4. Relaxed acceptor site specificity has been reported for C. lari and Desulfovibrio desulfuricans PglB homologs5,6. However, this has only been shown for one very unique site (271DNNNST276) in the C. jejuni AcrA acceptor protein. PglBCl did not glycosylate the wild-type CH2 domain of a human IgG15. In our hands, PglBCj and PglBCl were able to transfer Man3GlcNAc2 to extended sites (Supplementary Fig. 12c) but not to minimal glycosylation sites in engineered or eukaryotic target proteins (data not shown). Another issue is that only a small fraction (<1%) of each expressed protein was glycosylated under the conditions tested here. With that said, the yield of glycosylated proteins has reached up to ~50 μg/L in our hands and might be further improved by increasing expression in the periplasm, relieving enzymatic and metabolic bottlenecks, and/or optimizing the glycosylation enzymes. Along these lines, simple optimization strategies have previously been used to generate nearly 25 mg/L of bacterial glycoproteins in E. coli9. We anticipate further improvements will be achieved by applying new glyco-display technologies including cell surface and phage display systems17,23,24. Such methods will be needed to create bacterial OTase variants that efficiently glycosylate minimal N-X-S/T acceptor sites. Alternatively, novel bacterial OTases with distinct properties6 or single-subunit eukaryotic OTases25 could prove useful. Overall, the engineering of defined glycosylation pathways in E. coli sets the stage for further engineering of this host for the production of vaccines and therapeutics with even more structurally complex human-like glycans. Moreover, glycoengineered E. coli has the potential to serve as a model genetic system for deciphering the “glycosylation code” which governs the non-template driven synthesis of diverse glycans and their specific attachment to proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Imperiali for plasmid pBAD(ALG2)-DEST49, George O’Toole for plasmid pMQ70, Tom Mansell for helpful discussions regarding RNaseA glycosylation, Chang Hong for helpful discussions regarding glycan synthesis, and the Functional Genomic Center Zürich for input and instrument support. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Career Award CBET-0449080 (to M.P.D.), the New York State Office of Science, Technology and Academic Research Distinguished Faculty Award (to M.P.D.), the National Institutes of Health Small Business Innovation Research grants R43 GM087766 and R43 GM086965 (to A.C.F), the National Institutes of Health NCRR grant 1 P41 RR018502-01 (to the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center) and a graduate fellowship from LASPAU and the Universidad Antonio Nariño (to J.D.V.-R.).

Footnotes

Author contributions. J.D.V.-R. designed research, performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper. A.C.F. designed research, performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper. J.H.M. designed research and performed research. Y.-Y.F. performed MS analysis and analyzed data. C.A.R. performed research. K.C. performed research. C.H. and P.A. performed NMR analysis and analyzed data. M.A. designed research and analyzed data. M.P.D. designed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Competing financial interests. A.C.F., J.H.M., and C.A.R. are employees of Glycobia, Inc. A.C.F., J.H.M., C.A.R., and M.P.D. have a financial interest in Glycobia, Inc.

References

- 1.Helenius A, Aebi M. Science. 2001;291:2364–9. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szymanski CM, Yao R, Ewing CP, Trust TJ, Guerry P. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1022–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wacker M, et al. Science. 2002;298:1790–3. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5599.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kowarik M, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:1957–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz F, et al. Glycobiology. 2011;21:45–54. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ielmini MV, Feldman MF. Glycobiology. 2011;21:734–42. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weerapana E, Imperiali B. Glycobiology. 2006;16:91R–101R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman MF, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500044102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ihssen J, et al. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz F, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:264–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandhal J, Wright PC. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32:1189–98. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Patten SM, et al. Glycobiology. 2007;17:467–78. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Reilly MK, Zhang G, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9593–603. doi: 10.1021/bi060878o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Couto JR, Huffaker TC, Robbins PW. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:378–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Weldeghiorghis T, Zhang G, Imperiali B, Prestegard JH. Structure. 2008;16:965–75. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilg K, Yavuz E, Maffioli C, Priem B, Aebi M. Glycobiology. 2010;20:1289–97. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher AC, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:871–81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01901-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alaimo C, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:967–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cipollo JF, Trimble RB, Chi JH, Yan Q, Dean N. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21828–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lizak C, Gerber S, Numao S, Aebi M, Locher KP. Nature. 2011;474:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, et al. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6081–7. doi: 10.1021/ac060516m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowarik M, et al. Science. 2006;314:1148–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1134351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celik E, Fisher AC, Guarino C, Mansell TJ, DeLisa MP. Protein Sci. 2010;19:2006–2013. doi: 10.1002/pro.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durr C, Nothaft H, Lizak C, Glockshuber R, Aebi M. Glycobiology. 2010;20:1366–72. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasab FP, Schulz BL, Gamarro F, Parodi AJ, Aebi M. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3758–68. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.