Abstract

Background

Coronary stents, drug-eluting stents in particular, have been linked to coronary epicardial endothelial dysfunction after implantation. However, less is known about their impact on coronary microvascular function and their long-term effects on the vasculature.

Methods and Results

We evaluated 71 patients (mean age 53.0±10.1 years) with chest pain and angiographically non-significant coronary artery disease 17.1±17.1 months after left anterior descending artery stenting. 71 age- and sex matched patients (mean age 53.0±10.3 years) with chest pain but no prior coronary intervention served as control. Coronary blood flow (CBF) in response to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine as well as the microvascular (endothelium-independent) coronary flow reserve (CFR) in response to intracoronary adenosine was evaluated. Quantitative coronary angiography was used to study epicardial diameter changes to Ach. Microcirculatory function was not significantly different between the groups (stenting vs control, CFR 2.9 [2.5, 3.4] vs 3.0 [2.4, 3.4], p =0.24 and % change of CBF 34.9 % [−34.4, 90.0] vs 54.7 % [−5.6, 104.6], p=0.18). Both groups exhibited epicardial endothelial dysfunction (−23.0 % [−47.4, −7.6] vs −20.0 % [−40.0, 0.0], p=0.4). Results did not differ between patients with drug-eluting (n=46) and bare metal stents (n=24).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that in patients with coronary arteries in which a stent has been placed, coronary microcirculatory and epicardial vascular function are not significantly different from that of an age and sex-matched population with similar symptoms but non-significant coronary artery disease.

Keywords: endothelial function, coronary stent, microcirculation, coronary artery disease

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with balloon angioplasty and adjuvant coronary stenting has become an efficacious treatment in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD).1 However, catheter-based coronary interventions are associated with arterial injury, resulting in endothelial dysfunction.2 Several studies have reported the presence of focal endothelium dependent vasomotor dysfunction in both proximal and distal non-stented reference segments of coronary arteries 6 to 12 months post-stent implantation both in patients with sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents.3–8 This might raise concerns that these segments are at higher risk for future events.9 Furthermore, recent studies pointed out that endothelial dysfunction after stent implantation could be linked to long-term clinical outcome, such as stent thrombosis.10–12 In addition to the well recognized effect of stents on epicardial endothelial function in the shorter term, little is known about vascular function after more than 1 year. Additionally the effect of stents on coronary microvascular function, an important measure for the integrity of the microvasculature and a prognosticator for future coronary events13, 14 is not known.

Interestingly, a substantial number of patients after stent-implantation continue to have recurrent symptoms and need further angiograms, although in many, no residual obstructive lesion can be detected. Thus microvascular dysfunction could contribute to the recurrent symptoms. However, the association between coronary microvascular function and coronary artery stenting in patients with chest pain in the absence of obstructive CAD is uncertain.

It was therefore the aim of this study to evaluate microvascular and epicardial vascular function in patients with recurrent chest pain after stenting and compare them to a similar age and sex matched control group with chest pain but a normal coronary angiogram. Additionally we were interested in any differences between those patients receiving a DES and a BMS, respectively.

METHODS

Patient Population

This is a retrospective analysis of patients followed in the Mayo Clinic Rochester Catheterization Lab Registry from March 1998 to December 2011. In the “Stent-group” 71 consecutive patients referred for evaluation of chest pain (Canadian Cardiovascular Society class III angina or less) in the absence of obstructive CAD (> 30%) on coronary angiogram were included. Out of these, 24 originally received a bare metal stent (BMS) and 46 a drug eluting stent (DES) into the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. 71 age and sex matched patients with chest pain and normal coronary angiogram (absence of obstructive coronary artery disease) and no prior coronary intervention severed as control.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: histories of coronary artery bypass graft surgery, ejection fraction of 50% or less, valvular heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, significant endocrine, hepatic, renal, or inflammatory disease and inability to obtain informed consent from the patient. Patient demographics and laboratory data, including fasting lipid profile and serum glucose, were obtained. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Measurement of coronary microvascular function

Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed by a standard percutaneous femoral approach. The methodology for coronary endothelial function analysis has been described previously.15, 16 In brief, heparin 5,000 U was given intravenously and a Doppler guidewire (FloWire, Volcano Corp., Rancho Cordova, CA, USA) was positioned within a coronary infusion catheter (Ultrafuse, SciMed Life Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in the mid-portion of the LAD coronary artery. Velocity signals were instantaneously obtained from the Doppler wire by an online fast Fourier transform, and average peak velocities (APV) were determined.

Intracoronary bolus injections of incremental doses (18–60 μg) of adenosine were administered until maximal hyperemia was achieved (or the highest dose was given) to evaluate endothelium-independent microvascular coronary flow reserve (CFR). CFR was calculated by dividing peak APV after adenosine by APV at baseline. Subsequently, to assess coronary blood flow (CBF), the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (Ach) was selectively infused at increasing concentrations (10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 mol/L) for 3 minutes at each concentration into the LAD artery. Coronary artery diameter and APV were measured, and CBF was calculated after each infusion of Ach (the maximal tolerable dose of Ach was used). CBF was calculated from the Doppler-derived time velocity integral and vessel diameter as π(coronary artery diameter/2)2 × (APV/2),17 where CBF is flow (mL/min), coronary artery diameter is the vessel diameter (mm) by quantitative coronary angiography. These methods have been validated previously17, 18 and analysis of data from our laboratory demonstrates a variation in repeated measurements of 8+3%. Endothelium-dependent microvascular dysfunction was defined as ≤50% increase in CBF in response to the maximal dose of Ach compared with baseline.17, 18 Endothelium-independent microvascular function was defined as a CFR ratio of < 2.5. Coronary microvascular dysfunction was defined as endothelium-dependent dysfunction and/or endothelium-independent dysfunction.9, 18

Epicardial coronary endothelial function measurements by Quantitative Coronary Angiography

Quantitative measurements of the coronary arteries were obtained with a computer-based image-analysis system (IMPAX cardiovascular review station, Agfa HealthCare, Mortsel, Belgium). Segment diameters were determined at baseline and after both ACh and nitroglycerin administration. The reference segment was not exposed to Ach and thus served as a control segment. Coronary diameter was analyzed from digital images using a modification of a previously described technique from this institution.17 In brief, the changes in LAD diameter were measured in 2 segments distal to the stent. The “distal segment” was defined as the segment 5mm distal to the tip of the Doppler wire (which translates to about 5–10mm distal to the distal stent margin) and as the “far distal segment” defined as the segment beginning more than 10 mm distal from the first segment. An end-diastolic cine frame at each infusion (baseline, Ach and NTG) was selected, and calibration of the video and cine images was accomplished with the diameter of the guide catheter identified. All off-line measurements of coronary artery diameter were performed by an experienced operator who was unaware of results of the coronary reactivity data and the type of stent.

Statistics

Continuous data are summarized as the mean ± standard deviation, if approximately normally distributed, otherwise median and interquartile ranges (25%; 75%) are stated. To compare the matched controls to the stented group, conditional logistic regression was employed. Unpaired t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to compare the continuous distributions between BMS and DES groups; Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to test categorical variables between BMS and DES groups. A value of p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Patients Characteristics

The total study population consists of 142 patients, 71 in each group. In the 71 patients of the “stent group” (mean age 53.0±10.1 years, 36 men) the mean time between PCI of the LAD artery and the actual measurement was 17.1±17.1 months. Among them, 24 patients received a BMS and 46 a DES (17 sirolimus, 15 paclitaxel and 4 everolimus eluted stents; 10 remained unidentified) in average 19.8±15.9 and 15.3±17.6 months respectively, p = 0.31, before endothelial function measurement. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. In general, patients in the stent group had a higher prevalence in traditional cardiovascular risk factors (all patients had stents originally placed due to significant CAD) and more cardiovascular medications than in the matched control group. However, most hemodynamic and laboratory characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristic

| Variables | Prior Stent (N=71) | Control (N=71) | P value† | DES (n=46) | BMS (n=24) | P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 53.0 ± 10.1 | 53.0 ± 10.3 | 0.90 | 52.3 ± 9.9 | 54.3 ± 10.8 | 0.42 |

| Male, n (%) | 36 (51%) | 36 (51%) | 25 (54%) | 10 (42%) | 0.31 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 41 (59%) | 31 (44%) | 0.06 | 31 (67%) | 10 (42%) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (6%) | 12 (17%) | 0.041 | 3 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0.69 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 61 (87%) | 42 (59%) | < .001 | 39 (85%) | 21 (91%) | 0.45 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.35 | 0.10 | ||||

| Never smoked | 24 (34%) | 37 (52%) | 13 (29%) | 11 (46%) | ||

| Former smoker | 39 (56%) | 23 (32%) | 26 (58%) | 12 (50%) | ||

| Current smoker | 7 (10%) | 11 (15%) | 6 (13%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Family history, n (%) | 53 (76%) | 43 (61%) | 0.05 | 36 (78%) | 17 (74%) | 0.69 |

| ACE Inhibitor use, n (%) | 19 (27%) | 16 (23%) | 15 (33%) | 4 (17%) | 0.15 | |

| Beta Blocker use, n (%) | 36 (51%) | 19 (27%) | 0.004 | 27 (59%) | 9 (38%) | 0.09 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker use, n (%) | 37 (52%) | 22 (31%) | 0.015 | 19 (41%) | 18 (75%) | 0.007 |

| Lipid Lowering Drug use, n (%) | 57 (80%) | 30 (42%) | <.001 | 38 (83%) | 18 (75%) | 0.45 |

| Nitrates use, n (%) | 44 (62%) | 33 (47%) | 0.09 | 31 (67%) | 13 (54%) | 0.28 |

| Time from Implantation to Study | 17.1 ± 17.1 | 15.3 ± 17.6 | 19.8 ± 15.9 | 0.31 |

- P-value based on conditional logistic regression to account for matched pairs

- P-value based on two-sample tests (t-test, chi-squared test)

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme

Table 2.

Hemodynamic and laboratory data

| Variable | Prior stent (N=71) | Control (N=71) | P value† | DES (n=46) | BMS (n=24) | P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, Median (Q1, Q3) | 160.0 (136.0, 194.0) | 169.0 (151.0, 204.0) | 0.32 | 154 (134.0, 199.0) | 167 (138.0, 191.0) | 0.77 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL, Median (Q1, Q3) | 81.0 (61.0, 109.0) | 98.0 (76.0, 121.0) | 0.010 | 75 (59.0, 115.0) | 90.0 (68.0, 108.0) | 0.43 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.08 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.63 |

| Glycosolated Hemoglobin, %, Median (Q1, Q3) | 5.4 (5.2, 5.8) | 5.4 (5.2, 5.7) | 0.42 | 5.4 (5.2, 5.7) | 5.5 (5.2, 5.9) | 0.63 |

| hs CRP, mg/L, Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.9 (0.4, 3.0) | 0.7 (0.3, 2.3) | 0.40 | 1.1 (0.4, 3.0) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) | 0.009 |

| BNP, pg/mL, Median (Q1, Q3) | 34.5 (20.0, 68.0) | 22.0 (13.0, 58.0) | 0.017 | 34.0 (20.0, 68.0) | 49.0 (14.0, 74.0) | 0.95 |

| MAP, mmHg | 100.9 ± 14.9 | 100.0 ± 12.1 | 0.78 | 101.3 ± 15.3 | 99.7 ± 14.3 | 0.69 |

| Heart rate, bpm, Median (Q1, Q3) | 68.0 (63.0, 75.0) | 70.0 (62.0, 77.0) | 0.95 | 70.0 (63.0, 76.0) | 67.0 (630, 75.0) | 0.67 |

| Body Mass Index | 29.4± 5.6 | 29.8± 7.0 | 0.70 | 29.4 ± 6.1 | 29.2 ± 4.7 | 0.90 |

- P-value based on conditional logistic regression to account for matched pairs

- P-value based on two-sample tests (rank sum, t-test)

Data are presented as mean value ± SD, the median (interquartile). LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; MAP, mean arterial pressure

In patients who received a DES, compared to a BMS, there were no significant differences among the study groups about age, sex, body mass index and cardiovascular risk factors. The frequency of cardiovascular medications did not differ. Data for hemodynamics, including biochemical parameters, are also indicated Table 2.

Endothelium-dependent microvascular endothelial function

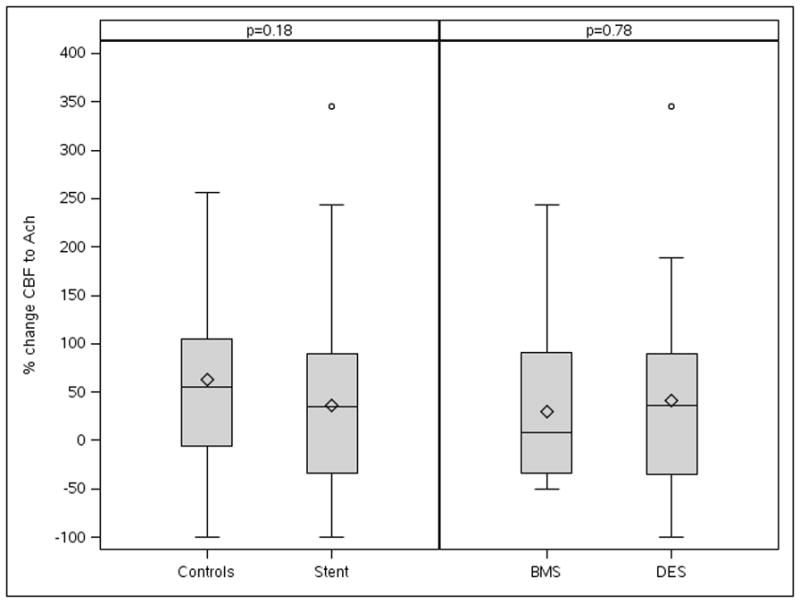

Baseline CBF was lower in the stent group, compared to the age and sex-matched control group (37.7 [25.3, 48.6] vs 50.6 [39.7, 72.7] mL/min, p< 0.05). However, endothelial microvascular function (change in CBF after Ach infusion) was not different between both groups (34.9 [−34.4, 90.0] vs 54.7 [−5.6, 104.6] %, p=0.18) (Figure, Table 3). Abnormal coronary endothelium-dependent microvascular function was present in 38 (57%) patients in stent group and 33 (47%) patients in control group (p=0.25), respectively.

Figure.

Figure depicts a mean percent change of CBF between the stenting and control group in response to Ach infusion did not show significant difference. CBF, coronary blood flow; BMS = bare metal stent; DES = drug-eluting stent

Table 3.

Coronary Microvascular endothelial function

| Variable | No stent (N=71) | Prior stent (N=71) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max CFR, Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.0 (2.4, 3.4) | 2.9 (2.5, 3.4) | 0.24 |

| CFR<2.5, No. (%) | 19 (27%) | 15 (21%) | 0.27 |

| % chg CBF(Ach), Median (Q1, Q3) | 54.7 (−5.6, 104.6) | 34.9 (−34.4, 90.0) | 0.18 |

| % chg. CBF<50%, No. (%) | 33 (47%) | 38 (57%) | 0.25 |

- P-value based on conditional logistic regression to account for matched pairs

Data are presented as mean value ± SD, the median (interquartile). BMS, bare metal stent; DES, drug-eluting stent; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CBF, coronary blood flow; Ach, acetylcholine

Endothelium-independent microvascular endothelial function

Mean CFR, as measured with adenosine, was not different between the stent group and control group (2.9 [2.6, 3.5] vs 2.7 [2.4, 3.3], p=0.39). Both groups had a similar number of patients with impaired CFR (15 [21%] and 19 [27%], p=0.27) (Table 3).

Coronary microvascular endothelial function between DES and BMS

There was no significant difference between DES and BMS group with respect to change in CBF (35.9 [−35.1,−90.0] vs 8.6 [−34.4, 91.0] %, p=0.78) and CFR (2.9 [2.6, 3.5] vs 2.7 [2.4, 3.3], p=0.39) (Figure, Table 3). The frequency of abnormal microvascular function was not significantly different between both groups (DES vs BMS, CFR < 2.5; 8 [17%] vs 7 [29%], p = 0.25, change of CBF < 50%; 23 [53%] vs 14 [61%], p = 0.56). There was no significant difference in microvascular function by follow-up duration, either (Table 4).

Table 4.

Change of Microvascular endothelial function by follow-up duration in Stenting group

| Variable | <=6 months (N=22) | 6–12 months (N=14) | >12 months (N=33) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max CFR, median (Q1, Q3) | 3.3 (2.7, 3.7) | 2.7 (2.4, 3.1) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.4) | 0.10 |

| CFR<2.5, n (%) | 2(9%) | 5(36%) | 8 (24%) | 0.15 |

| BL CBF, median (Q1, Q3) | 39.5 (25.5, 48.2) | 33.6 (25.4, 45.7) | 38.5 (27.5, 55.4) | 0.70 |

| CBF (Hyperemia), median (Q1, Q3) | 47.5 (19.7, 97.9) | 38.2 (27.1, 76.8) | 48.5 (16.8, 94.2) | 0.85 |

| % chg CBF(Ach), median (Q1, Q3) | 17.0 (−51.2, 78.3) | 68.2 (20.0, 90.0) | −4.1 (−37.9, 101.8) | 0.42 |

| % chg. CBF<50%, n (%) | 14 (67%) | 4 (31%) | 19 (61%) | 0.10 |

- P-values based on rank sum and chi-squared tests

Data are presented as mean value ± SD, the median (interquartile). Abbreviations are as in Table 3.

Epicardial vascular function

QCA data for both groups are shown in Table 5. Resting baseline distal epicardial diameters were larger in control group than stent group (2.3±0.6 vs, 2.0±0.5 mm, p< 0.05). However, Ach induced percent changes in coronary artery diameter revealed no significant difference between the stent group and control group (−9.5 [−23.1, 0.0] vs −19.8 [−33.3, 0.0] %, p=0.33). In both groups endothelial dysfunction was present, as shown by vasoconstriction to Ach. Furthermore there was no difference between patients treated with DES or BMS (−21.0 [−34.2, 0.0], −14.0 [−31.5, 4.3], p = 0.37). Intracoronary NTG induced an endothelial-independent vasodilation of all evaluated vessel segment, without difference between both groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Epicardial endothelial function

| Variable | No stent (N=71) | Prior stent (N=71) | P Value† | DES (n=46) | BMS (n=24) | P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL distal diameter | 2.3± 0.6 | 2.0± 0.5 | 0.003 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.36 |

| %chg. diameter, distal to stent, Median (Q1, Q3) | −9.5(−23.1, 0.0) | −19.8(−33.3, 0.0) | 0.33 | −21.0(−34.2, 0.0) | −14.0(−31.5, 4.3) | 0.37 |

| %chg. diameter (NTG), distal to stent, Median (Q1, Q3) | 11.6(4.3, 19.6) | 11.0(−1.5, 22.0) | 0.76 | 10.0(0.0, 21.4) | 14.3(−1.5, 33.3) | 0.41 |

| BL far distal diameter | 1.6± 0.4 | 1.5± 0.4 | 0.07 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.82 |

| %chg. diameter, far distal, Median (Q1, Q3) | −20.0(−40.0, 0.0) | −25.0(−47.4, −7.6) | 0.40 | −30.0(−40.7, −8.1) | −22.2(−50.0, −5.2) | 0.84 |

| %chg. diameter (NTG), far distal, Median (Q1, Q3) | 13.3(0.0, 26.5) | 14.5(3.2, 28.6) | 0.61 | 14.3(5.1, 33.7) | 15.4(0.0, 25.0) | 0.49 |

- P-value based on conditional logistic regression to account for matched pairs

- P-value based on two-sample tests (t-test, rank sum test)

Data are presented as mean value ± SD, the median (interquartile); NTG, nitroglycerin; other abbreviations are as in Table 3.

Confidence intervals and statistical power

Given the negative findings, we calculated confidence intervals for the median difference between matched cases and controls (Table 6). The confidence interval for max CFR shows that the data is consistent under the possibility that CFR is typically 0.20 higher in controls as well as the possibility that CFR is 0.37 lower in controls. This range is fairly narrow given the inter-quartile ranges of 1.0 and 0.9 in controls and stented patients, respectively. Additionally, 71 paired responses should provide 80% power to detect a standardized effect size of 0.34 (i.e. one-third of the standard deviation) with a paired t-test. In general, these results indicate that we are not likely missing out on any large group differences.

Table 6.

Median differences and 95% confidence intervals

| Parameter | Median difference† | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Max CFR | −0.10 | −0.37, 0.20 |

| % chg CBF(Ach) | −0.97 | −26.4, 39.9 |

| %chg. diameter, distal to stent | 5.88 | −4.7, 16.7 |

| %chg. diameter (NTG), distal to stent | 0.00 | −11.3, 7.7 |

| %chg. diameter, far distal | 7.82 | −10.2, 16.0 |

| %chg. diameter (NTG) | −1.68 | −5.4, 7.1 |

- Differences are calculated within matched pairs as control response minus stent patient response

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates non-significant differences in coronary microvascular function after more than a year following stent implantation as compared to age and sex matched patients without stents and only minimally diseased vessels. Remarkably, microvascular function did not differ, based on whether a DES or BMS was used. Furthermore, epicardial coronary endothelial function, although dysfunction was present in both groups and irrespective of stent type, was not different between the groups as well.

While recently, effect of stents, DES in particular, on epicardial endothelial function has been studied, the effect of stent implantation on the downstream microvasculature has not been evaluated thoroughly, although the coronary microcirculation is crucial for myocardial blood flow and myocardial perfusion regulation.17, 19 In this study we found non-significantly different microvascular function as compared to a control population with similar symptoms but non significant coronary artery disease. Thus one can argue that microvascular coronary function in patients with chest pain is irrespective of prior stent implantation. Remarkably, microvascular function did not differ in those patients who received a DES as compared to those with a history of bare metal stenting.

There are several possible explanations for our findings. Importantly the evaluation of endothelial function has been performed on average over one year after stent implantation, thus the microvascular endothelium may have recovered from periprocedural injury and the potentially deleterious effects of drugs released by DES subsided. It has been shown that 30 days after DES placement, drug-release from the stent is only minimal.20 However, we cannot exclude, that a potential persistent negative effect of stent implantation on the endothelium was abrogated by statins or other cardiovascular medications more often used in the ‘stent’ group and which have been shown to have a positive effect on the vasculature.21 However, statin use was not different in the DES as compared to the BMS group.

A recent study reported a deterioration of the coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction between 6 and 12 months after DES implantation22 and another study in porcine coronary vasculature pointed out a differential effect of DES on microvascular function, given that sirolimus-eluting stents did not affect vascular function, whereas paclitaxel-eluting stents did.23 In our study we did not find any difference in microvascular function between BMS and DES treated groups after an average of more than 12 month and there was no difference between the different types stents used. At least in our study population, which was characterized by recurrent chest pain, a population that is likely to suffer form microvascular associated problems, microvascular function was not different compared to the control group and importantly not between those with a DES as compared with a BMS.

The other important finding of our study is that we did not find any difference in epicardial endothelial function in patients with chest pain and a stent history as compared to similar patients with chest pain but no stent history. Furthermore, despite the recent demonstration of endothelial dysfunction after DES implantation, epicardial vascular function was not significantly different between patients with a BMS and a DES. In our population, however, most patients were characterized by epicardial endothelial dysfunction as demonstrated by vasoconstriction after Acetylcholine infusion, a condition typical for atherosclerotic vessels. It may be speculated that the presence of endothelial function at this period of time (again after an average of more than 12 month after stent implantation) is related to the presence of coronary artery disease and not the effect of stenting, with DES in particular.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between coronary stenting, irrespective of BMS or DES, and epicardial endothelial function and raised concerns of continuous vascular injury following PCI and the potential effect on thrombosis and potentially myocardial ischemia.3, 4, 6–8, 24–27 Moreover, mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction after stent implantation remain incompletely defined, but recent work has provided several possible mechanisms including direct toxic effect from the entrapped drug and/or acute or delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the polymer or drug and delayed reendothelialization with inadequate endothelial coverage was proposed.5–7, 28, 29 Additionally, stent placement frequently produces dissection of the media and adventitia. These events induce focal inflammation in the injured vessel, which may cause endothelial dysfunction.25, 30 Furthermore, several recent studies implicated a differential effect of DES on endothelial function,5, 7, 31 the mechanism of which is not clear, but may be secondary to the specific drug or the polymer of the stent.3, 4, 6 In our study, although we found epicardial dysfunction, no difference between the different stent groups were found in the long term (more than 1 year after stent implantation).

Study limitations

This is a retrospective study and the limitations of potential selection bias have to be taken into account. Although we tried to match the control population as closely as possible, there are some differences between the control and the ‘stent’ group, potentially affecting the results. All patients were referred because of chest pain and had undergone coronary angiography based on clinical indications. However, those patients in the stent group all have recently received a stent due to significant coronary artery disease thus potentially representing a sicker population with more cardiovascular risk factors than the non-stent group. However, in the light of these differences, our non-significant findings in the difference in endothelial micro- and macrovascular function are especially intriguing as the combination of atherosclerosis and previous stent implantation would argue rather for worse vascular function compared to the control group. On the other hand, as outlined above, the higher frequency of statin use and other cardioprotective medications in the stent group could have an opposite effect. Importantly, there were no differences between the DES and the BMS group in respect of medications and risk factor distribution.

To overcome the limitation of a matched control group, it would have been elegant to compare the effect of stent implantation on microvascular function with non-stented vessels in the same patient. However, in this study, in order to assess the effect on the microcirculation, the administration of the acetylcholine was directly into the LAD and thus other arteries were not exposed. Another potential limitation is that baseline endothelial function before stent implantation was not assessed in our study. However, the assessment of endothelial function in patients with significant coronary lesions is not practical.

Conclusion

We here demonstrate that in patients with a stent in the coronary arteries, coronary microcirculatory and epicardial vascular function were not significantly different to that of an age and sex-matched population with similar symptoms but non-significant coronary artery disease, a finding that was irrespective of the stent type implanted. Thus our study does not support a long term worsening of vascular function by drug eluting stent implantation.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Coronary stenting has been linked to epicardial endothelial dysfunction with a consecutive risk for future events

Although no residual obstructive lesion can be found, a substantial number of patients after stent-implantation continue to have recurrent symptoms, which might be attributed to microvascular dysfunction

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

The study adds knowledge about microcirculatory and epicardial vascular function in patients with a history of stent implantation presenting with chest pain

A long term worsening of vascular function by drug eluting stent implantation is not supported

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jonella Tilford for her expert technical help.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH HL 92954, HL085307, HL77131, DK73608, AG 31750) and the Mayo Foundation. AJF was supported by the Walter and Gertrud Siegenthaler Foundation, the young academics Support Committee of the University of Zurich, and the Swiss foundation for medical-biological scholarships (SSMBS; SNSF No PASMP3_132551).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Topol EJ, Serruys PW. Frontiers in interventional cardiology. Circulation. 1998;98:1802–1820. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mc Fadden EP, Bauters C, Lablanche JM, Quandalle P, Leroy F, Bertrand ME. Response of human coronary arteries to serotonin after injury by coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1993;88:2076–2085. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuke S, Maekawa K, Kawamoto K, Saito H, Sato T, Hioka T, Ohe T. Impaired endothelial vasomotor function after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circ J. 2007;71:220–225. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofma SH, van der Giessen WJ, van Dalen BM, Lemos PA, McFadden EP, Sianos G, Ligthart JM, van Essen D, de Feyter PJ, Serruys PW. Indication of long-term endothelial dysfunction after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:166–170. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togni M, Windecker S, Cocchia R, Wenaweser P, Cook S, Billinger M, Meier B, Hess OM. Sirolimus-eluting stents associated with paradoxic coronary vasoconstriction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin DI, Kim PJ, Seung KB, Kim DB, Kim MJ, Chang K, Lim SM, Jeon DS, Chung WS, Baek SH, Lee MY. Drug-eluting stent implantation could be associated with long-term coronary endothelial dysfunction. Int Heart J. 2007;48:553–567. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Togni M, Raber L, Cocchia R, Wenaweser P, Cook S, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM. Local vascular dysfunction after coronary paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JW, Suh SY, Choi CU, Na JO, Kim EJ, Rha SW, Park CG, Seo HS, Oh DJ. Six-month comparison of coronary endothelial dysfunction associated with sirolimus-eluting stent versus Paclitaxel-eluting stent. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerman A, Zeiher AM. Endothelial function: cardiac events. Circulation. 2005;111:363–368. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153339.27064.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG, Schofer J, Dawkins KD, Morice MC, Colombo A, Schampaert E, Grube E, Kirtane AJ, Cutlip DE, Fahy M, Pocock SJ, Mehran R, Leon MB. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, Abrecht L, Vaina S, Morger C, Kukreja N, Juni P, Sianos G, Hellige G, van Domburg RT, Hess OM, Boersma E, Meier B, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E, Kutys R, Skorija K, Gold HK, Virmani R. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Zalos G, Mincemoyer R, Prasad A, Waclawiw MA, Nour KR, Quyyumi AA. Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;106:653–658. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025404.78001.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Targonski PV, Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, Holmes DR, Jr, Lerman A. Coronary endothelial dysfunction is associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events. Circulation. 2003;107:2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072765.93106.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavi S, Prasad A, Yang EH, Mathew V, Simari RD, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Smoking is associated with epicardial coronary endothelial dysfunction and elevated white blood cell count in patients with chest pain and early coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115:2621–2627. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.641654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raichlin E, Prasad A, Kremers WK, Edwards BS, Rihal CS, Lerman A, Kushwaha SS. Sirolimus as primary immunosuppression is associated with improved coronary vasomotor function compared with calcineurin inhibitors in stable cardiac transplant recipients. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1356–1363. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasdai D, Gibbons RJ, Holmes DR, Jr, Higano ST, Lerman A. Coronary endothelial dysfunction in humans is associated with myocardial perfusion defects. Circulation. 1997;96:3390–3395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Jr, Lerman A. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101:948–954. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wohrle J, Nusser T, Merkle N, Kestler HA, Grebe OC, Marx N, Hoher M, Kochs M, Hombach V. Myocardial perfusion reserve in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Correlation to coronary microvascular dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:781–787. doi: 10.1080/10976640600737649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serruys PW, Kutryk MJ, Ong AT. Coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:483–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra051091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reriani MK, Dunlay SM, Gupta B, West CP, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Effects of statins on coronary and peripheral endothelial function in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18:704–716. doi: 10.1177/1741826711398430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyamoto Y, Okura H, Kume T, Kawamoto T, Neishi Y, Hayashida A, Yamada R, Imai K, Obase K, Yoshida K. Coronary microvascular endothelial function deteriorates late (12 months) after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. J Cardiol. 2010;56:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Heuvel M, Sorop O, Batenburg WW, Bakker CL, de Vries R, Koopmans SJ, van Beusekom HM, Duncker DJ, Danser AH, van der Giessen WJ. Specific coronary drug-eluting stents interfere with distal microvascular function after single stent implantation in pigs. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grewe PH, Deneke T, Machraoui A, Barmeyer J, Muller KM. Acute and chronic tissue response to coronary stent implantation: pathologic findings in human specimen. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caramori PR, Lima VC, Seidelin PH, Newton GE, Parker JD, Adelman AG. Long-term endothelial dysfunction after coronary artery stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1675–1679. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilos MI, Ostojic M, Beleslin B, Sagic D, Mangovski L, Stojkovic S, Nedeljkovic M, Orlic D, Milosavljevic B, Topic D, Karanovic N, Wijns W. Differential effects of drug-eluting stents on local endothelium-dependent coronary vasomotion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2123–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Beusekom HM, Whelan DM, Hofma SH, Krabbendam SC, van Hinsbergh VW, Verdouw PD, van der Giessen WJ. Long-term endothelial dysfunction is more pronounced after stenting than after balloon angioplasty in porcine coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maekawa K, Kawamoto K, Fuke S, Yoshioka R, Saito H, Sato T, Hioka T. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Severe endothelial dysfunction after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2006;113:e850–851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.597948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murakami D, Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S, Ohba T, Seino Y, Mizuno K. Novel neointimal formation over sirolimus-eluting stents identified by coronary angioscopy and optical coherence tomography. J Cardiol. 2009;53:311–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welt FG, Rogers C. Inflammation and restenosis in the stent era. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1769–1776. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000037100.44766.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilos M, Sarma J, Ostojic M, Cuisset T, Sarno G, Melikian N, Ntalianis A, Muller O, Barbato E, Beleslin B, Sagic D, De Bruyne B, Bartunek J, Wijns W. Interference of drug-eluting stents with endothelium-dependent coronary vasomotion: evidence for device-specific responses. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:193–200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.797928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]