Abstract

This paper summarizes the findings for the East and South East Asia Region of the WPA Task Force on Steps, Obstacles and Mistakes to Avoid in the Im-plementation of Community Mental Health Care. The paper presents a description of the region, an overview of mental health policies, a critical ap-praisal of community mental health services developed, and a discussion of the key obstacles and challenges. The main recommendations address the needs to campaign to reduce stigma, integrate care within the general health care system, prioritize target groups, strengthen leadership in policy mak-ing, and devise effective funding and economic incentives.

Keywords: Community mental health care, East and South East Asia, mental health policies, non-governmental organizations, human rights, family involvement, target groups, economic incentives

This paper is part of a series describing the development of community mental health care in the various regions of the world (see 1,2,3,4,5,6), produced by the Task Force appointed by the WPA as part of its Action Plan 2008-2011 7,8. The WPA Guidance on Steps, Obstacles and Mistakes to Avoid in the Implementation of Community Mental Health Care, developed by the Task Force, has been published in this journal 9. In this article, we describe these issues in relation to East and South East Asia.

The region includes 15 countries (4 in East Asia and 11 in South East Asia), with marked cultural, religious, and socioeconomic diversity. All these countries devote only a small fraction of their total health budget to mental health (less than 1% in low income countries; less than 5% in high income countries) 10. Because of varied historical backgrounds and colonial heritages, health care systems diverge even among neighbouring countries.

OVERVIEW OF MENTAL HEALTH POLICIES IN THE REGION

Table 1 shows the presence of mental health policies and laws in the region. Despite 20 years of effort, China does not yet have a national mental health law, but it has instituted a mental health plan 15, while Hong Kong has a mental health ordinance 16. In Thailand, mental health legislation came into effect in 2008 14.

Table 1.

Table 1 Mental health policies and laws in countries of East and South East Asia

| Mental health legislation | |||

| Present | Absent | ||

| Mental health policy or programme | Present | Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, North Korea, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand | Cambodia, China, Laos, Philippines, Viet Nam |

| Absent | Brunei | Timor-Leste | |

| Sources: Jacob et al 11, World Health Organization 12, Tebayashi 13, Thailand Mental Health Act 14 | |||

Family involvement is a characteristic of the region. Even in Singapore and Malaysia, where the Western influence is quite prevalent, the family plays a major role in the patient’s admission and treatment. Involuntary admission with family consent is legalized in Japan and South Korea. China also permits involuntary admission with family consent, although the practice is not legalized, and the legal guardians include not only family members but also public officers 17.

The legislation ensures community integration in Japan, Malaysia, Mongolia, and South Korea, while the rest in the region has community-based mental health care policies or programmes, except for Burnei and Laos 12.

OVERVIEW OF MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES IN THE REGION

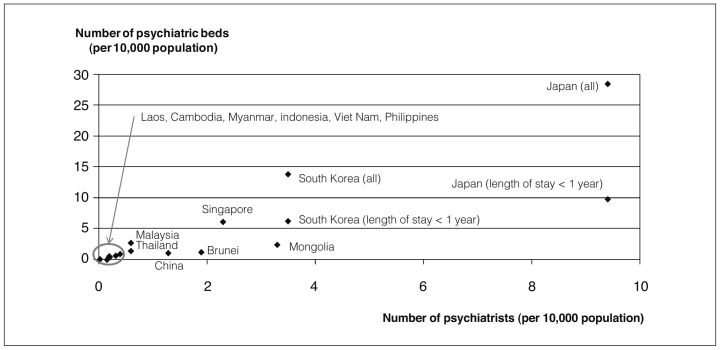

The number of psychiatrists and of psychiatric beds per 10,000 population are shown in Figure 1, except for East-Timor. Japan has the highest number of psychiatrists per 10,000 people in the region (9.4), followed by South Korea (3.5), Mongolia (3.3), and Singapore (2.3). Despite a recent decrease in admissions, Japan (28.4) has also the highest number of psychiatric beds, followed by South Korea (13.8). Mongolia also maintains a hospital-based care system with an occupancy rate of above 80% 18.

Figure 1 Number of psychiatrists and psychiatric beds in countries of East and South East Asia Sources: Jacob et al (11), World Health Organization (12).

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have set up model mental health services, and trained both health care and non-health workers in post-conflict countries, such as Cambodia and East-Timor, where all mental health resources were destroyed 12,19,20. In Malaysia, local NGOs provide residential care, day-care services and psychosocial rehabilitation services in the community 18. In the Philippines, collaborative activities between local NGOs and university groups compensate for the government’s limitations 21. Most NGOs’ activities cover screening and assessment, and talking treatments. Psychological, rather than Western-style phamacological treatment, is popular in these countries.

Home care and day hospital services are used as alternatives to hospital admission in several countries of the region. In Singapore, a mobile crisis team (community nurses assisted by a medical officer or a medical social worker) conducts home visits for crisis intervention, while community psychiatric nursing teams offer home care to discharged patients living in the community, including assessment and monitoring and psychological support to their caregivers 22.

In China, psychiatric hospitals send professionals to the homes of persons with severe mental disorders to provide “home-bed” services 23,24. For persons with chronic mental disorders, sheltered workshops for rehabilitation and a “rural guardianship network” for their supervision and management are also available, but their effectiveness is controversial 24,25. In China, non-government services such as private psychiatric clinics, non-professional counselling clinics, telephone hotlines, and folk treatments are becoming the dominant form of community mental health services, but their sustainability is of concern 15,26.

Most early intervention and assertive community treatments are provided in pilot specialized community mental health projects. In the Philippines, more than 7,000 patients were hospitalized in the mental hospital in Manila; however, the introduction of acute crisis intervention services reduced this number by more than half 27.

Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia have introduced assertive community treatment (ACT) with cultural modifications. A Japanese study in pre- and post-pilot phase reports the reduction of length of stay, while a subsequent randomized clinical trial shows a decrease of inpatient days and higher Client Evaluation of Services-8 (CSQ-8) scores in an ACT group compared to a control group 28. In South Korea, in a pre-post comparison, the number and duration of the admissions were also dramatically reduced and the clinical and social outcomes were significantly improved 29,30. In Singapore, the ACT programme was effective in reducing the frequency and duration of admissions in a clinical trial. The employment status of patients also showed improvement over the course of study 31.

Chronic beds for long-stay patients are being converted into residential facilities and group homes in communities, such as the private nursing homes of Malaysia 32.

In Malaysia and Thailand, community mental health promotion and prevention activities are conducted through public places, such as schools, churches, temples, and community halls 18.

Asia is vulnerable to natural disasters, including earthquakes and floods. These tragic disasters often deepen awareness of the need to develop community mental health systems. Mental health and psychosocial support are included in disaster preparedness in Indonesia 33, Myanmar 34 and Thailand 35. In Indonesia, a community mental health nursing training programme was developed after the Tsunami 36.

OBSTACLES AND CHALLENGES

Human rights

Traditional beliefs that mental illness is caused by malicious spirit possession or weak character persist in several countries of the region. According to a national survey in South Korea, people often consider mental illnesses to be self-limiting disorders that will resolve on their own 37. Much stigma is still attached to persons with mental illness, as well as to psychiatric institutions and services 22. One study in Singapore found that the main predictors of people seeking help were not availability and access to care but perceptions of mental illness and health care 38. Public misconceptions about mental illness result in prejudice which leads to discrimination. There is a gap between the legal framework and the reality of the mentally ill, who are often abused in many countries 39.

Family involvement

Strong family involvement in mental health care is a characteristic of Asia 40. Family plays an essential role in the care of people with mental disorders in the community; however, the poor knowledge of mental illness and negative attitudes about the patient prevents many people in need from seeking care 40. Many persons with mental illness are abandoned by their families. The establishment of partnerships with families and the assignment of necessary resources are priorities in the region.

Traditional healers

In many Asian countries, it is common for people to consult traditional healers for their health problems even if medical services are available. Healers rarely cooperate with each other, nor do they collectively work with formal health care providers 32. Cambodians often seek help from Kru Khmer, who are mainly herbalists 41, and it is also common to consult traditional healers in East-Timor 20. Families often bring the patient to religious healers first, although the government of Viet Nam prohibits this act 42. In Indonesia, up to 80% of people consult traditional healers as a first resort 43. The 1993 survey in Singapore shows 30% of patients in a national hospital visited traditional healers, dukun, before consulting physicians 44. Such behaviour is one of the reasons for the low formal service use in the region.

Distribution of services and continuity of care

Mental health services are available only in certain areas of a country. Most people with severe mental disorders are unable to access services in low-resource countries, and mental health resources are centralized in large cities in medium-resource countries. In Japan and South Korea, policy proposals exist to convert current long-term psychiatric care beds to outpatient/ambulatory clinics or long-term community-based care, but in reality, many discharged patients have failed to make use of such services. A survey in South Korea shows a high readmission rate immediately after discharge 45, while one in Malaysia reports a lower rate of followed-up and treated patients at one year 46. South Korea is quickly developing a comprehensive mental health service system in each catchment area 47. In Japan, people lack an awareness of the “catchment area” due to the negative effects of the universal insurance system which is the greatest contribution to Japanese health 48.

Funding

Most of the countries in the region are seeking to balance the public and private financing and provision of care. Funds for development of community services usually come from savings made from the reduction of beds in hospitals, but such cutbacks and increasing community services are not always balanced. Furthermore, in rapidly aging countries, community services are urgently needed for people with dementia. There is a concern that most of the mental health budgets will be spent on treating those with this disease. If the boundary between mental health and elderly care becomes unclear, a smaller amount of money will be earmarked for people with severe and persistent mental disorders.

LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Legal process and anti-stigma campaign

A legal process is needed to protect the human rights of persons with mental illness in countries without appropriate legislation. In Japan, the mental health act legally acknowledges for the first time that mental illness is a disability, and stricter criteria and a psychiatric review board for involuntary admissions have been established after a series of scandals regarding human rights violation 49. In the context of anti-stigma campaigns, renaming schizophrenia has been well accepted in Japan and Hong Kong 50,51. Similar movements are seen in other East Asian countries where Chinese characters are used.

Integration into the general health system

The best way to create a cost-effective system is to utilize the existing general medical sector, providing training of primary health workers. Singapore has been successful in preparing general practitioners for providing mental health care, with psychiatrists’ support 52. Primary care is generally more acceptable by persons with mental disorders and their families 52. Collaborative networks are needed among stakeholders to avoid fragmentation and must include service-users/families, hospitals, community health workers, NGOs, and traditional healers 53.

Prioritization of target groups

Due to limited resources, we have to prioritize care. Compared to depression or mild mental disorders, which are generally more accepted and better funded, persons with severe and persistent mental disorders are often missed and left behind in planning and budgeting. Prioritized services should be provided to severely disabled persons.

Leadership and policy making

Strong leadership is needed to navigate changes. Very few mental health professionals are actively involved in policymaking. Consequently, the lack of leadership allows the allocation of more money or resources to general health care services rather than to mental health. It is not uncommon that non-mental health professionals have negative attitudes toward mental illness. It is necessary to change their ways of thinking.

Not only central but also local governments need to participate in the development of sustainable community mental health care systems. In recent times, former patients have more opportunities to speak publicly and participate in mental health policy making 54.

Funding and economic incentives

The overall mental health budget should be increased. Financial insecurity keeps persons with mental illness and their families from seeking medical services. It is essential to develop a funding system in which all people who need help are able to receive care.

Economic incentives are necessary to promote community-based mental care services. Hospitals and mental health professionals are reluctant to shift to the community because of poorer funding and lower salaries 24. Transitional costs may be necessary for retraining mental health workers. ACT and employment support are not fully covered by medical expenditures. A flexible financial structure over medical and social boundaries is required.

CONCLUSIONS

After a long history of asylum, a slow deinstitutionalization is occurring in East and Southeast Asia. Now this region is in a transition period from institutional to community care. Unlike the West, Asian countries fear the confusion engendered by rapid change; they are cautiously reducing psychiatric beds, and simultaneously trying to build community services. This attempt has not yet been successful, mainly because of system fragmentation. Role differentiation is required between the hospitals and community services, and the public and private services. Ensuring the quality of care is the next challenge for community mental health care. We can learn lessons from other regions in constructing the future of mental health care in East and South Asia.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank for their contribution Drs. M.R. Phillips (China); H. Diatri and E. Viora (Indonesia); T. Akiyama, J. Ito, Y. Kim and N. Shinfuku (Japan); S. Ann, H.C. Chua and K.E. Wong (Singapore); T.-Y. Hwang (South Korea); and B. Panyayong (Thailand).

References

- 1.Hanlon C, Wondimagegn D, Alem A. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Africa. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:185–189. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semrau M, Barley E, Law A. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Africa. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:217–225. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake RE, Latimer E. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in North America. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGeorge P. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Australasia and the South Pacific. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razzouk D, Gregório G, Antunes R. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Latin American and Caribbean countries. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:191–195. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2012.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thara R, Padmavati R. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in South Asia. World Psychiatry. doi: 10.1002/wps.20042. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maj M. Mistakes to avoid in the implementation of community mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:65–66. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maj M. Report on the implementation of the WPA Action Plan 2008-2011. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:161–164. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornicroft G, Alem A, Dos Santos RA. WPA guidance on steps, obstacles and mistakes to avoid in the implementation of community mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:67–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena A, Sharan P, Saraceno B. Budget and financing of mental health services: baseline information on 89 countries from WHO’s Project Atlas. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003;6:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet. 2007;370:1061–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Mental health atlas 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tebayashi Y. Cambodia. In: Shinfuku N, Asai K, editors. Mental health in the world. Tokyo: Health Press; 2009. pp. 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of the Council of State, Thailand. Mental health act. www.thaimentalhealthlaw.com.

- 15.Liu J, Ma H, He YL. Mental health system in China: history, recent service reform and future challenges. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:210–216. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Editorial. What we should consider when we next amend the mental health ordinance of Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2009;19:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokai M. China. In: Shinfuku N, Asai K, editors. Mental health in the world. Tokyo: Health Press; 2009. pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asia-Australia Mental Health. Summary report: Asia-Pacific Community Mental Health Development Project. 2008 www.aamh.edu.au.

- 19.Somasundaram DJ, van de Put WA, Eisenbruch M. Starting mental health services in Cambodia. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1029–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwi AB, Silove D. Hearing the voices: mental health services in East-Timor. Lancet. 2002;360:s45–s46. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conde B. Philippines mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:159–166. doi: 10.1080/095402603100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei KC, Lee C, Wong KE. Community psychiatry in Singapore: an integration of community mental health services towards better patient care. Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2005;15:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson V. Community and culture: a Chinese model of community care for the mentally ill. Int J Soc Psychiatry . 1992;38:163–178. doi: 10.1177/002076409203800301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips MR. Mental health services in China. Epidemiol Psichiatria Soc. 2000;9:84–88. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00008253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu F, Lu S. Guardianship networks for rural psychiatric patients. A non-professional support system in Jinshan County, Shanghai. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;24:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips MR. The transformation of China’s mental health services. China Journal. 1998;39:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akiyama T, Chandra N, Chen N. Asian models of excellence in psychiatric care and rehabilitation. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:445–451. doi: 10.1080/09540260802397537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito J, Oshima I, Nisho M. Initiative to build a community-based mental health system including assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness in Japan. Am J Psychiatr Rehab. 2009;12:247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J. Presented at the 10th Congress of the World Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Bangalore: 2009. Nov, Cost effectiveness of modified ACT program in Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Kim S, Ki S. Presented at the 161st Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington: 2008. May, Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) in Korea: preliminary 7 months follow-up study . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fam J, Lee C, Lim BL. Assertive community treatment (ACT) in Singapore: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deva PM. Malaysia – Mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:167–176. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001635203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setiawan GP, Viora E. Disaster mental health preparedness plan in Indonesia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:563–566. doi: 10.1080/09540260601037920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Htay H. Mental health and psychosocial aspects of disaster preparedness in Myanmar. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:579–585. doi: 10.1080/09540260601108952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panyayong B, Pengjuntr W. Mental health and psychosocial aspects of disaster preparedness in Thailand. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:607–614. doi: 10.1080/09540260601038514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasetiyawan, Viola E, Maramis A. Mental health model of care programmes after the tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:559–562. doi: 10.1080/09540260601039959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho SJ, Lee JY, Hong JP. Mental health service use in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:943–951. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng TP, Jin AZ, Ho R. Health beliefs and help seeking for depressive and anxiety disorders among urban Singaporean adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:105–108. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irmansyah I, Prasetyo YA, Minas H. Human rights of persons with mental illness in Indonesia: more than legislation is needed. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3():14–14. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373:2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins W. Medical practitioners and traditional healers: a study of health seeking behavior in Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia. www.cascambodia.org. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uemoto M. Viet Nam. In: Shinfuku N, Asai K, editors. Mental health in the world. Tokyo: Health Press; 2009. pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pols H. The development of psychiatry in Indonesia: from colonial to modern times. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:363–370. doi: 10.1080/09540260600775421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida N. ASEAN countries. In: Shinfuku N, Asai K, editors. Mental health in the world. Tokyo: Health Press; 2009. pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee MS, Hoe M, Hwang TY. Service priority and standard performance of community mental health centers in South Korea: a Delphi approach. Psychiatry Invest. 2009;6:59–65. doi: 10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salleh MR. Decentralization of psychiatric services in Malaysia: what is the prospect? Singapore Med J. 1993;34:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. WHO-AIMS report on mental health system in Republic of Korea. Republic of Korea: Gwacheon City: World Health Organization and Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito H. Quality and performance improvement for mental healthcare in Japan. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:619–622. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283318ea5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito H, Sederer LI. Mental health services reform in Japan. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1999;7:208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen E, Chen C. Presented at the 2nd World Congress of Asian Psychiatry. Taipei: 2009. Nov, The impact of renamed schizophrenia in psychiatric practice in Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato M. Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective. World Psychiatry. 2006;5:53–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lum AW, Kwok KW, Chong SA. Providing integrated mental health services in the Singapore primary care setting – the general practitioner psychiatric programme experience. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallcraft J, Amering M, Freidin J. Partnerships for better mental health worldwide: WPA recommendations on best practices in working with service users and family carers. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:229–236. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuno E, Asukai N. Efforts toward building a community-based mental health system in Japan. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2000;23:361–373. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(00)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]