Abstract

Background

This study investigated the regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), the histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)–nuclear receptor coreceptor (NCoR) complex (a corepressor of transcription used by PPARγ), and small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) (a posttranslational modifier of PPARγ) in human adipose tissue and both adipocyte and macrophage cell lines. The objective was to determine whether there were alterations in the human adipose tissue gene expression levels of PPARγ, HDAC3, NCoR, and SUMO-1 associated either with obesity or with treatment of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) subjects with insulin-sensitizing medications.

Methods

We obtained subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies from 86 subjects with a wide range of body mass index (BMI) and insulin sensitivity (SI). Additionally, adipose tissue biopsies were obtained from a randomized subgroup of IGT subjects before and after 10 weeks of treatment with either pioglitazone or metformin.

Results

The adipose mRNA levels of PPARγ, NCoR, HDAC3, and SUMO-1 correlated strongly with each other (P<0.0001); however, SUMO-1, NCoR, and HDAC3 gene expression were not significantly associated with BMI or SI. Pioglitazone increased SUMO-1 expression by 23% (P<0.002) in adipose tissue and an adipocyte cell line (P<0.05), but not in macrophages. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of SUMO-1 decreased PPARγ, HDAC3, and NCoR in THP-1 cells and increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induction in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Conclusions

These results suggest that the coordinate regulation of SUMO-1, PPARγ1/2, HDAC3, and NCoR may be more tightly controlled in macrophages than in adipocytes in human adipose and that these modulators of PPARγ activity may be particularly important in the negative regulation of macrophage-mediated adipose inflammation by pioglitazone.

Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) is a nuclear receptor required for adipocyte development and normal glucose homeostasis.1,2 The mechanism of transcriptional regulation by PPARγ is complex because it activates or represses transcription by recruiting coactivator or corepressor complexes to gene promoters. For example, PPARγ recruits coactivator complexes to the promoter of the aP2 gene.3 In contrast, PPARγ recruits the histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)–nuclear receptor coreceptor (NCoR) corepressor complex to the promoter of the glycerol kinase gene (GyK) to repress transcription, which can be relieved by thiolidazinedione (such as pioglitazone, an insulin sensitizer) binding to PPARγ, which then recruits coactivators to upregulate GyK transcription.3 In response to agonists, PPARγ also exerts broad antiinflammatory effects in macrophages and other cell types,4,5 and this activity has been correlated with the insulin-sensitizing activities of synthetic PPARγ agonists. This antiinflammatory mechanism of repression is distinct from the regulation of GyK, because monomeric PPARγ prevents the clearance of the NCoR–HDAC3 corepressor complex from the promoter of inflammatory genes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (INOS) in a ligand-dependent manner.5 An interesting aspect of this model is that synthetic PPARγ agonists promote the conjugation of small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) to the PPARγ ligand binding domain, and SUMOylation of PPARγ is required to stabilize the complex.5 Thus, the transrepression of inflammatory genes by PPARγ is one of many transcriptional pathways that are negatively regulated by SUMOylation.

In this study, we have examined the messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of PPARγ, SUMO-1, NCoR, and HDAC3 in subcutaneous human adipose tissue and in adipocyte and monocyte/macrophage cell lines to determine the relationship between the expression of these genes and obesity. Furthermore, we determined whether pioglitazone or metformin modulates the expression of these genes. The results of this study indicate that these genes are important targets in the complex mechanism of insulin sensitization by pioglitazone.

Research Design and Methods

Human subjects

All subjects provided written informed consent under protocols that were approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and the studies were conducted at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences/Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System General Clinical Research Center. Nondiabetic subjects were recruited by local advertisement. Subjects were included if their fasting glucose was less than 126 mg/dL and their 2-h postchallenge glucose was less than 199 mg/dL, as determined by an initial 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Subjects were excluded from the study if they had a history of coronary artery disease or were taking medications affecting adipose tissue metabolism, such as corticosteroids, fibrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers. Insulin sensitivity was measured using a frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIGT). On the basis of the OGTT, subjects were defined as having either normal glucose tolerance (NGT) (2-h glucose <140 mg/dL) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (2-h glucose 140–199 mg/dL). A total of 86 subjects were recruited (70 women and 16 men, 21–66 years old), of which 54 were NGT and 32 were IGT. Subjects had a wide range of body mass index values (BMI) (19–55 kg/m2), percent body fat (15.5%–54.1%), and insulin sensitivity (SI) (0.62–26.8×10−4 min−1/μU/mL]. The IGT subjects were randomly treated with either pioglitazone or metformin for 10 weeks. Following a 10-week period of treatment, the OGGT and FSIGT and the biopsies were repeated.

Although the total sample size of this study included 86 subjects, data were unavailable on some subjects for some measurements. Hence, the number of subjects reported for each correlation is less than the total sample size.

Cell culture, small interfering RNA treatment, and mRNA and protein expression analysis

Human Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome (SGBS) preadipocytes were cultured as described,6,7 and adult-derived human stem cells (ADHASC) were cultured and differentiated as described.8 THP-1 monocytes were maintained and induced to differentiate into polarized macrophages by cytokine treatment [M1, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon-γ; M2a, interleukin-4 (IL-4); and M2c, IL-10] as described.9 The cells were then incubated with or without 3 μM pioglitazone as indicated and harvested for analysis. For small interfering RNA (siRNA) studies, THP-1 cells were transfected in six-well plates with 25 nmol siRNA and 10 μL of TransIT-TKO transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI). The cells were incubated for 24 h and analyzed for gene or protein expression. To determine whether SUMO-1 knockdown affected inflammatory responses or the ability of pioglitazone to repress inflammatory responses, THP-1 cells treated with or without SUMO-1 siRNA were further treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (vehicle control) or pioglitazone (3 μM) for 24 h and then treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 6 h. Total RNA from cell lines or from whole adipose tissue was isolated and analyzed as described previously.9 Protein extracts were prepared from the cells in cell lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 1-X protease inhibitor cocktail (EMD Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany)]. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a control. Forty micrograms of protein was resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel and immunoblotted with the indicated antibody. Antibodies against PPARγ2 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), and antibodies against HDAC3 and NCoR were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The membranes were imaged and quantified with an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) using actin as a control, as described.10

Statistics

All data were expressed as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM); the Student t-test was used for statistical analysis, and the paired t-test was used for paired data. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) mRNA expression was described with means and standard errors by LPS treatment, pioglitazone treatment, and SUMO-1 siRNA treatment. A three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the main effects of LPS, pioglitazone treatment, SUMO-1 siRNA, and all possible interactions. Interactions with a type 3 test for effect P values greater than 0.2 were removed from the final ANOVA model. Post hoc t-test comparisons were made when interactions were suggested in the final model (P<0.05). SAS v9.3 was used for all statistical tests and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

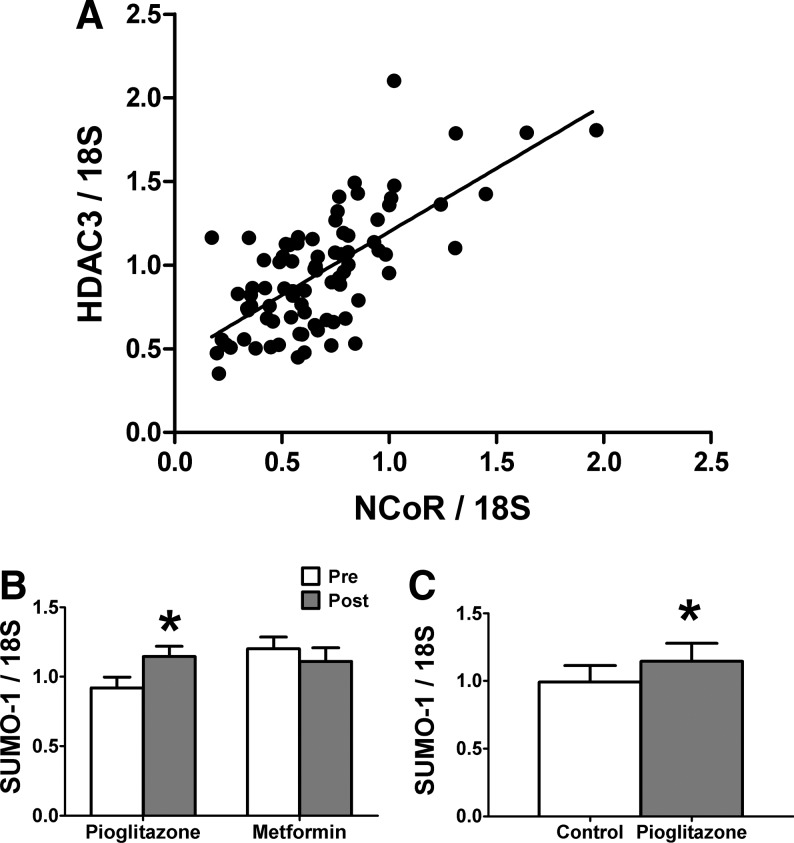

We examined the expression of PPARγ, SUMO-1, NCoR, and HDAC3 mRNA in human whole adipose tissue from a large set of subjects (Table 1) with IGT or NGT. We quantified gene expression levels by real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, normalized expression to 18S, and then determined correlations. We found that PPARγ2 mRNA expression was correlated positively with BMI (n=75, r=0.36, P=0.015) and was negatively correlated with SI (n=75, r=−0.24, P=0.04), consistent with previous results.11 PPARγ2 mRNA expression was correlated positively with CD68 (n=86, r=0.52, P<0.0001) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (n=85, r=0.53, P<0.0001) expression (Table 2), suggesting that PPARγ2 correlates with macrophage infiltration. Although the mRNA levels of SUMO-1, NCoR, or HDAC3 were not significantly correlated with either BMI or SI (data not shown), there were significant correlations in the levels of these genes when compared to each other (Table 2). For instance, HDAC3 mRNA levels were strongly correlated with NCoR mRNA levels (n=84, r=0.69, P<0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 1A). Both NCoR and HDAC3 were also positively correlated with PPARγ2, with r values of 0.40 and 0.45, respectively (Table 2). PPARγ2 expression was also positively correlated with the expression of SUMO-1 (n=85, r=0.40, P<0.0001; Table 2). Thus, the mRNA levels of PPARγ2, SUMO-1, NCoR, and HDAC3 are tightly correlated in human adipose tissue. Finally, MCP-1 and CD68 in adipose tissue were also correlated with NCoR, HDAC3, and SUMO-1 mRNAs (Table 2).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics and Effect of Metformin and Pioglitazone Treatmenta

| Variable | All subects | Metformin-treated subects | Pioglitazone-treated subects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) | 70/16 | 9/3 | 15/3 |

| Age, years | 21–66 | 32–54 | 35–56 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 19–55 | 30–38 | 25–38 |

| Body fat, % | 15.5–54.1 | 23–48 | 30–47 |

| SI Pretreatmentb | 0.62–26.8 | 1.94±0.25 | 1.74±0.13 |

| SI Posttreatmentb | Not Applicable | 1.74±0.15 | 2.43±0.24c |

Inclusion criteria were a fasting glucose level less than 126 mg/dL and 2 h postchallenge glucose less than 199 mg/dL (determined by a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test). Exclusion criteria were a history of coronary artery disease or if the subjects were taking corticosteroids, fibrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers.

×10−4 min−1 (μU/mL).

P=0.006, compare pretreatment to postreatment.

F/M, female/male; BMI, body mass index; SI, insulin sensitivity.

Table 2.

mRNA Correlations (P<0.0001) in Human Adipose Tissuea

| Gene 1 | Gene 2 | rb |

|---|---|---|

| PPARγ2 | SUMO-1 | 0.42 |

| PPARγ2 | NCoR | 0.40 |

| PPARγ2 | HDAC3 | 0.45 |

| HDAC3 | NCoR | 0.69 |

| HDAC3 | SUMO-1 | 0.69 |

| NCoR | SUMO-1 | 0.80 |

| SUMO-1 | CD68 | 0.40 |

| NCoR | CD68 | 0.51 |

| HDAC3 | CD68 | 0.47 |

| PPARγ2 | CD68 | 0.52 |

| SUMO-1 | MCP1 | 0.63 |

| NCoR | MCP1 | 0.62 |

| HDAC3 | MCP1 | 0.53 |

| PPARγ2 | MCP1 | 0.53 |

Subjects (n=84–86) with a wide range of BMI and SI were analyzed for the expression of the indicated genes.

The mRNA levels of the indicated genes were normalized to the levels of 18S RNA, and Pearson correlation coefficients and P values were determined.

PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; SUMO-1, small ubiquitin-like modifier-1; NCoR, nuclear receptor coreceptor; MCP1, monocyte chemo attractant protein-1.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of gene expression in human adipose biopsies and cell lines. (A) Correlation of histone deacetylase-3 (HDAC3) and nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) mRNA expression in 84 subjects. (B) Effect of pioglitazone and metformin treatment on the expression level of small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) mRNA in human whole adipose tissue. Open columns indicate pretreatment and shaded columns indicate posttreatment of subjects with the indicated drugs. The data are presented as means±standard error (SE) (n=18 for pioglitazone; n=13 for metformin). (*) Compare pretreatment and posttreatment with pioglitazone (P<0.05). (C) Effect of pioglitazone treatment on the expression level of SUMO-1 in the human adipocyte Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome (SGBS) cell line. Differentiated SGBS cells were treated with or without pioglitazone as indicated. The data are presented as means±SE (n=3). (*) Compare pioglitazone treatment with control (P<0.05).

Next, we examined the influence of a 10-week treatment period with either pioglitazone or metformin on the expression of these genes in the adipose tissue of subjects with IGT. As shown in Fig. 1B, pioglitazone treatment increased the adipose tissue expression of SUMO-1 by 23% (P=0.0022), whereas metformin treatment did not result in a significant change. Neither NCoR nor HDAC3 expression levels changed with pioglitazone or metformin treatment (data not shown). Because adipose tissue consists of adipocytes, macrophages, and other cell types, we determined whether pioglitazone increased SUMO-1 expression in adipocytes or differentiated THP-1 macrophages in vitro. Pioglitazone treatment resulted in a significant increase of SUMO-1 mRNA expression only in adipocytes after 24 h (Fig. 1C), but it did not alter SUMO-1 expression in the differentiated THP-1 macrophages (data not shown). Therefore, the increase of SUMO-1 gene expression in human adipose tissue by pioglitazone is likely due to increased expression in adipocytes.

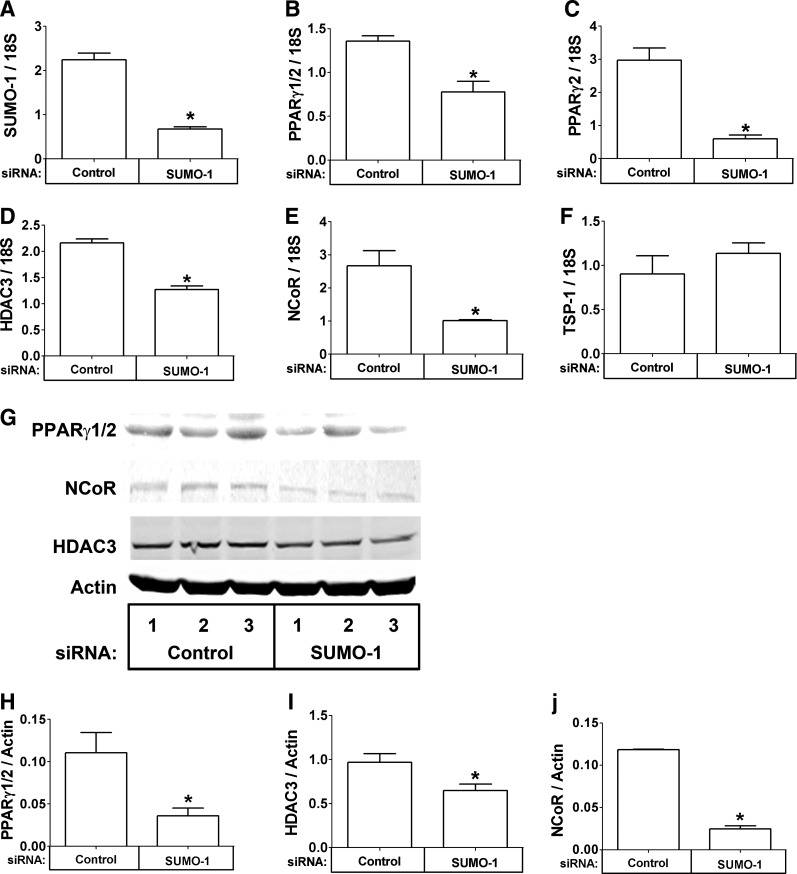

We next examined the close correlation among these genes and inflammation, specifically in THP-1 cells in vitro. THP-1 cells were transfected with control or SUMO-1 siRNA, and gene expression of SUMO-1, PPARγ1/2, PPARγ2, HDAC3, and NCoR was quantified. As expected, THP-1 cells treated with SUMO-1 siRNA contained less SUMO-1 mRNA than control siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 2A, P<0.05). Interestingly, the mRNA levels of PPARγ1/2, PPARγ2, HDAC3, and NCoR were also lower in SUMO-1 siRNA-treated cells than control-treated cells (Fig. 2B–E, P<0.05), but the levels of thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), which was quantified as a control, were not changed (Fig. 2F). The reduction in mRNA resulted in a reduction of the protein levels of PPARγ1/2, HDAC3, and NCoR (Fig. 2G, quantified in Fig. 2H–J, P<0.05). However, when differentiated ADHASC cells were treated with SUMO-1 siRNA, we did not observe a decrease in PPARγ2. Thus, coordinate regulation of SUMO-1, PPARγ1/2, HDAC3, and NCoR may be more tightly controlled in macrophages than in adipocytes.

FIG. 2.

Coordinate regulation of small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), histone deacetylase-3 (HDAC3), and nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) in THP-1 cells. (A–F) THP-1 cells were transfected with the indicated small interfering RNA (siRNA), and the mRNA expression of the indicated gene was measured with real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. (G) THP-1 cells (three replicates) were transfected with the indicated siRNA, and the protein level of the indicated gene was measured by immunoblotting. (H–J) Protein levels were quantified and normalized to actin. The data are presented as means±standard error (SE) (n=3). (*) Compare SUMO-1 siRNA treatment with control (P<0.05).

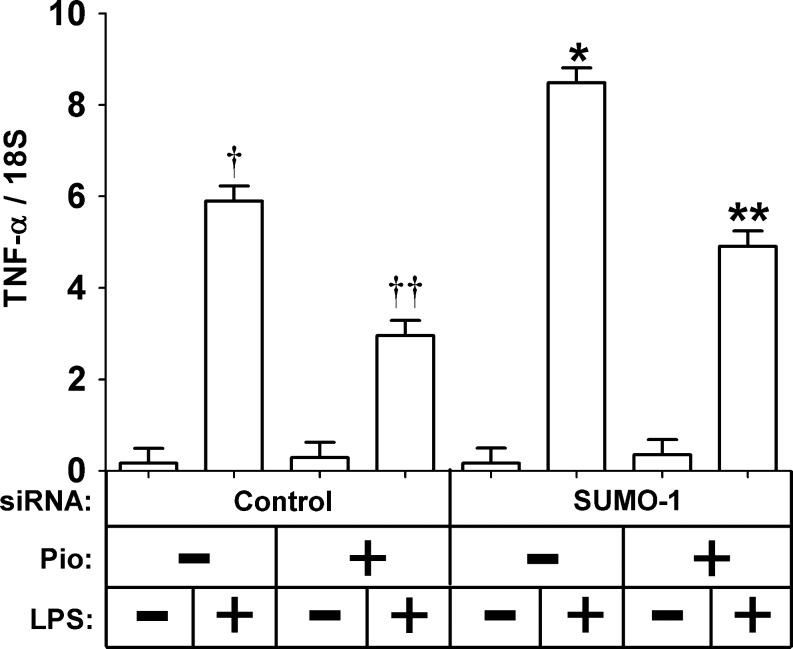

We next determined whether the reduction of SUMO-1 and the resulting reduction of PPARγ1/2, HDAC3, and NCoR reduced the ability of pioglitazone to repress the inflammatory response of the cells. THP-1 cells were transfected with control or SUMO-1 siRNA and then treated with or without pioglitazone (3 μM). The cells were then treated with LPS, and the induction of TNF-α mRNA was measured. As expected, LPS significantly induced TNF-α gene expression and pioglitazone repressed TNF-α mRNA induction regardless of SUMO-1 siRNA treatment (Fig. 3, P<0.05). However, there was a greater TNF-α mRNA induction in response to LPS when the cells were treated with SUMO-1 RNA (Fig. 3, P<0.05), suggesting that these genes are important in the negative regulation of macrophage-mediated adipose inflammation.

FIG. 3.

Effect of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) knockdown on the THP-1 cell inflammatory response. THP-1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA, treated with or without pioglitazone (3 μM), treated with or without 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 6 h, and the mRNA expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was measured with real-time reverse-transcriptase (RT)-PCR. The data are presented as means±standard error (SE) (n=4). (†) Compare LPS treatment with no LPS treatment (P<0.05); (††) compare LPS treatment with LPS and pioglitazone treatment (P<0.05); (*) compare LPS treatment with no LPS treatment (P<0.05); (**) compare LPS treatment with LPS and pioglitazone treatment (P<0.05). The overall effect of SUMO-1 knockdown on TNF-α induction was determined by three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P<0.05).

Discussion

PPARγ is a transcription factor that can activate or repress transcription, and PPARγ represses inflammatory genes in response to pioglitazone. The transrepression mechanism of genes that contain nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) sites in their promoter by PPARγ is complex and uses the HDAC3-NCoR corepressor complex.5 Recent studies in mice have demonstrated that cardiac depletion of HDAC3 causes aberrant expression of genes regulated by PPARα12 and that liver depletion of HDAC3 causes aberrant expression of genes regulated by Rev-erb-α.13 These studies suggest that reducing HDAC3 has dramatic effects on transcriptional repression. Because transcriptional repression is an important function of PPARγ, the goal of this study was to determine whether obesity or treatment with insulin-sensitizing drugs affected the human adipose tissue gene expression levels of PPARγ, the HDAC3-NCoR corepressor complex, and SUMO-1. Although the expression of these genes was not correlated with BMI or SI, strong correlations were observed when these genes were compared to each other. This suggests that these genes are coordinately regulated in human adipose, which is surprising because the HDAC3–NCoR corepressor complex is not restricted to use by PPARγ, but is used by many transcription factors. However, a recent study suggests that there is some specificity to the use of HDAC3 by Rev-erb-α in the liver.13,14 Our results show that knocking down the expression of SUMO-1 reduced PPARγ1/2, HDAC3, and NCoR expression and increased the inflammatory response of macrophages to LPS; however, SUMO-1 gene expression was not correlated with these genes in adipocytes by siRNA knockdown of SUMO-1. Thus, the HDAC3–NCoR corepressor complex may be regulated differently in different cell types in adipose tissue.

SUMO-1 gene expression specifically increased in the adipose tissue of subjects treated with pioglitazone and in cultured adipocytes following pioglitazone treatment. SUMOylation is a reversible posttranslational modification that occurs on the lysine residue of proteins15 SUMOylation alters the activity of a diverse set of proteins to regulate numerous cellular processes, including transcription and SUMOylation, has been linked to the control of metabolism.16 It is unclear why SUMO-1 increases in response to pioglitazone; however, SUMOylation has been implicated in adipogenesis since CEBPα, CEBPβ, and PPARγ, which are key regulators of adipogenesis, are modulated by SUMOylation.17–20 SUMOylation of PPARγ is also implicated in pioglitazone-mediated antiinflammatory effects5; however, SUMO-1 was increased in adipocytes, but not in differentiated macrophages, in response to pioglitazone. Although PPARγ, SUMO-1, HDAC3, and NCoR are not coordinately regulated in whole adipose tissue in response to pioglitazone, the genes are coordinately regulated in response to siRNA-mediated SUMO-1 knockdown in THP-1 cells, which exacerbates the inflammatory response in macrophages. Thus, HDAC3, NCoR, and SUMO-1 play complex roles in modulating PPARγ activity in adipose tissue during obesity and in response to synthetic PPARγ ligands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: DK80327 and UL1RR033173 (P.K.), DK71349 (C.P. and P.K.), AG20941 (C.P.), UL1RR029884 (R.M.), and M01RR14288 of the General Clinical Research Center and a Merit Review Grant from the Veterans Administration (N.R.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or Veterans Administration (VA). We would like to thank Bounleut Phanavanh, B.S., for his assistance with the RNA isolation and analysis. We would also like to acknowledge Heather Bush, Ph.D. for help with the statistical analysis of the data, and Regina Dennis for assistance with subject recruitment.

Author Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest or financial interests.

References

- 1.Spietelman BM. PPAR-gamma: Adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes. 1998;47:507–514. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willson TM. Lambert MH. Kliewer SA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and metabolic disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:341–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan HP. Ishizuka T. Chui PC. Lehrke M. Lazar MA. Corepressors selectively control the transcriptional activity of PPARgamma in adipocytes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:453–461. doi: 10.1101/gad.1263305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glass CK. Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascual G. Fong AL. Ogawa S, et al. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature 29. 2005;437:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wabitsch M. Brenner R.E. Melzner I, et al. Characterization of a human preadipocyte cell strain with high capacity for adipose differentiation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:8–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodles AM. Banga A. Rasouli N. Ono F. Kern PA. Owens RJ. Pioglitazone increases secretion of high-molecular-weight adiponectin from adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E1100–E1105. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00187.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasouli N. Yao-Borengasser A. Varma V, et al. Association of scavenger receptors in adipose tissue with insulin resistance in nondiabetic humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1328–1335. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer M. Yao-Borengasser A. Unal R, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages in insulin-resistant subjects are associated with collagen VI and fibrosis, demonstrate alternative activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E1016–E1027. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00329.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlin BS. Varma V. Nolen GT, et al. DHA reduces the atrophy-associated Fn14 protein in differentiated myotubes during coculture with macrophages. J Nutr Biochem. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.04.013. [published online 18 August 2011]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidal-Puig AJ. Considine RV. Jimenez-Linan M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene expression in human tissues. Effects of obesity, weight loss, and regulation by insulin and glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2416–2422. doi: 10.1172/JCI119424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery RL. Potthoff MJ. Haberland M, et al. Maintenance of cardiac energy metabolism by histone deacetylase 3 in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3588–3597. doi: 10.1172/JCI35847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng D. Liu T. Sun Z, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore DD. Physiology. Crise de foie, redux? Science. 2011;331:1275–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.1203194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson ES. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treuter E. Venteclef N. Transcriptional control of metabolic and inflammatory pathways by nuclear receptor SUMOylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita D. Yamaguchi T. Shimizu M. Nakata N. Hirose F. Osumi T. The transactivating function of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is negatively regulated by SUMO conjugation in the amino-terminal domain. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1017–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian L. Benson MD. Iniguez-Lluhi JA. A synergy control motif within the attenuator domain of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha inhibits transcriptional synergy through its PIASy-enhanced modification by SUMO-1 or SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9134–9141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eaton EM. Sealy L. Modification of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-beta by the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) family members, SUMO-2 and SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33416–33421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohshima T. Koga H. Shimotohno K. Transcriptional activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is modulated by SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29551–29557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]