Abstract

Therapeutic antibodies are well established drugs in diverse medical indications. Their success invigorates research on multi-specific antibodies in order to enhance drug efficacy by co-targeting of receptors and addressing key questions of emerging resistance mechanisms. Despite challenges in production, multi-specific antibodies are potentially more potent biologics for cancer therapy. However, so far only bispecific antibody formats have entered clinical phase testing. For future design of antibodies allowing even more targeting specificities, an understanding of the antigen-binding properties of such molecules is crucial. To this end, we have generated different IgG-like TriMAbs (trispecific, trivalent and tetravalent antibodies) directed against prominent cell surface antigens often deregulated in tumor biology. A combination of surface plasmon resonance and isothermal titration calorimetry techniques enables quantitative assessment of the antigen-binding properties of TriMAbs. We demonstrate that the kinetic profiles for the individual antigens are similar to the parental antibodies and all antigens can be bound simultaneously even in the presence of FcγRIIIa. Furthermore, cooperative binding of TriMAbs to their antigens was demonstrated. All antibodies are fully functional and inhibit receptor phosphorylation and cellular growth. TriMAbs are therefore ideal candidates for future applications in various therapeutic areas.

Keywords: ITC, receptor tyrosine kinase, SPR, therapeutic antibodies, trispecific antibodies

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are well established in clinical practice and more than 25 MAbs are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (An, 2010). Of these, about half are in use for treatment of cancer (Nieri et al., 2009). Despite these clinical successes, inhibition of an oncogenic driver protein with a therapeutic antibody often results in rapid emergence of resistance, rendering treatment ineffective (Pillay et al., 2009). A paradigm illustrating this concept is the ErbB receptor family, consisting of EGFR, Her2/ErbB2, Her3/ErbB3 and ErbB4, which propagate pro-survival signals by forming homo- or hetero-dimeric complexes on the cell surface. Inhibition of one of these receptors is often compensated by other human epidermal growth factor receptor family members or activation of other receptor tyrosine kinases (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001; Hynes and Lane, 2005; Hynes and MacDonald, 2009). To counter such tumor escape from single agent therapy, combinations of targeted therapies, as well as multi-specific low molecular weight inhibitors are being developed and have already entered clinical trials (Pivot et al., 2011).

Bispecific antibodies (BiAbs) provide another option to combine two tumor treatment approaches in a single therapeutic molecule. Using multi-specific antibodies rather than exploiting the polypharmacology of certain small molecule kinase inhibitors has the clear advantage that the target combination can be freely chosen and is clearly defined, whereas the combination of kinases that are hit by the same ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor is dictated by similarities in sequence and structure of the ATP-binding site (Vieth et al., 2005). While there is already clinical proof of concept for BiAbs recruiting immune effector cells, like bispecific T-cell engaging antibodies, BiAbs aimed at inhibiting signaling of two different tumor cell surface targets are just emerging in clinical trials (Chames and Baty, 2009a,b; Thakur and Lum, 2010). This delay is due to our still incomplete understanding of the complex biology of signaling networks that allows tumors to escape from targeted therapy by using certain alternative signaling routes. For treatment of diseases where ErbB receptor signaling is supposed to play a role, MM-111, targeting Her2/ErbB3 heterodimers (Nielsen et al., 2008), and MEHD7945A, targeting EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers (Schaefer et al., 2011), are considered promising combinations and both molecules have entered clinical trials (cf. clinicaltrials.gov).

Regarding the structural properties and possible formats of such molecules, a variety of bispecific constructs have been described in the past (Nieri et al., 2009; Kontermann, 2010; Thakur and Lum, 2010). It has also been demonstrated that BiAbs can bind to both antigens as well as FcγR family members simultaneously and therefore retain effector functions (Seimetz et al., 2010). For therapeutic applications, the selection of an appropriate format is directed by the biology of the targets (e.g. inhibitory, agonistic or downregulating antibody), as well as technical developability (Filpula, 2007; Mansi et al., 2010). As a consequence of this, the complexity of analyzing the binding properties of bi- or multi-specific antibodies increases with each additional specificity. Yet a thorough understanding of the binding properties is important since they affect efficacy.

In this work, we examined currently known resistance mechanisms in ErbB signaling, namely activation of the receptor tyrosine kinases cMet and IGF1R (Hynes and Lane, 2005), and evaluated the feasibility of generating novel trispecific antibodies which are either mono- or bivalent for some of these targets. For inhibition of ErbB signaling, inhibitory antibodies against EGFR and Her3 were selected (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001). They were combined with an antagonistic IGF1R antibody, since IGF1R can compensate for inhibition of EGFR (Hendrickson and Haluska, 2009; van der Veeken et al., 2009). We also combined them with a c-Met targeting antibody, since pre-clinical and clinical findings underscore the importance of cMet activation in ErbB signaling compromised tumor cells (Karamouzis et al., 2009; Bonanno et al., 2011). To fully exploit all antibody properties, Fc-containing scaffolds were chosen as these retain all possible effector functions and maintain the regular long serum half-life of an IgG antibody (Roopenian and Akilesh, 2007; Nimmerjahn and Ravetch, 2008).

By means of comprehensively analyzing their molecular features, we demonstrate the feasibility of generating trispecific antibody molecules, and investigate their simultaneous binding to all antigens, as well as provide evidence that these antibodies can bind at least with two specificities simultaneously on cells. Finally, the trispecific antibodies maintain all features of their parental antibodies and inhibited receptor activation equivalent to the parental antibodies, which makes them ideal candidates for future applications as anti-cancer agents.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

BxPc3 were obtained from ATCC. Cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), non-essential amino acids and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco). Propagation of cells followed standard cell culture protocols.

Antibodies and reagents

For immunoblot analysis p-EGFR (Epitomics), EGFR (Millipore), Her3, IGF1R (Santa Cruz), p-Her3, p-cMet, cMet, p-IGF1R (CST) and β-actin (Abcam) were purchased. For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis human IgG1 Mab versions of the TriMAbs were used for the determination of cell surface receptor expression. An α-human Alexa488 antibody (Invitrogen) was used as secondary antibody. Ectodomain Fc-chimera of EGFR, Her3, cMet with C-terminal His tag and FcγRIIIa were purified from cell culture supernatants of transiently transfected eukaryotic cells. Recombinant IGF1R was purchased (R&D). Human growth factor (HGF), heregulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) were purchased. Antibody sequences were derived from available patents (Kuenkele et al., 2005; Dennis et al., 2007; Bossenmaier et al., 2011; Umana and Mossner, 2011).

Design, cloning and production of TriMAbs

Sequences containing variable regions were ordered as gene synthesis with flanking restriction sites (GeneArt). Sequences were cloned in mammalian expression vectors with a cDNA organization of the antibody backbone. Antibody chains were transiently co-transfected in HEK-293F cells (Invitrogen) and purified as described (Metz et al., 2011). Antibody homogeneity was analyzed using an Agilent HPLC 1100 (Agilent Technologies) with a TSK-GEL G3000SW column (TosoHaas Corp.). Individual specificities of the MAbs are indicated by MAb <specificity>.

Dynamic light scattering analysis of TriMAbs

Molecule stability was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a DynaPro Plate Reader. Samples were filtered through a 0.45 µm 384-well filter plate into a 384-well clear bottom plate and covered with 15 µl of paraffin oil followed by a centrifugation step (1 min/1000 × g). Five acquisitions with 10 s acquisition time and five acquisitions with 20 s acquisition time were performed for temperature ramping and temperature stability experiments, respectively.

FACS competition experiments

For competition experiments, a 3-fold dilution series of either unlabeled Fabs or TriMAbs ranging from 100 to 0.002 µg/ml was prepared which also contained 1 µg/ml of AlexaFluor647 (Invitrogen) labeled MAbs. This mixture was added to a suspension of 2 × 105 BxPc3 cells. After 45 min of incubation cells were washed twice and subjected to flow cytometry (BD, FACS Canto).

Immunoblot

A total of 7 × 105 BxPc3 cells were seeded the day prior the experiment in starvation medium containing 0.5% FCS. The following day, cells were pre-incubated 30 min with 0.07 µM of the indicated antibodies upon which stimulation for 10 min with growth factors EGF (50 ng/ml), HGF (30 ng/ml), IGF (50 ng/ml) and Heregulin (500 ng/ml) followed. Upon cell lysis protein lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Proliferation assay

A total of 2500 BxPc3 cells per well were seeded the day prior to the experiment in 96-well plates in medium with 10% FCS. The following day, TriMAbs were added in the indicated concentrations and cells were maintained for a total of 144 h after antibody addition at 37°C/5% CO2. Proliferation was assessed by cell titer glow assay (Promega) in an Infinite M200 reader (Tecan).

Surface plasmon resonance

All experiments were performed on Biacore B3000, T100 and T200 instruments in running buffer phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween20. Dilution buffer consisted of running buffer supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. Standard amine coupling to 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide hydrochloride/N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide activated chip surfaces were performed as recommended by the provider GE Healthcare.

Kinetic characterization of single antigen binding to TriMAbs

Signals were double referenced against blank buffer and a flow cell containing no ligand. Kinetic constants were calculated from fitting to a 1 : 1 Langmuir-binding model (RI = 0). TriMAbs or MAbs were captured via α-human kappa light chain (Dako), human Fab binder (GE Healthcare) or α-human Fc (JIR). Series with increasing antigen concentrations were analyzed with an association phase of 180 s and dissociation phase of 800–1800 s depending on the kd-rate. Capture antibodies were regenerated with 10 mM glycine, pH 1.5 (25°C) or 1.75 (37°C), or for human Fab binder as recommended by the vendor. Monomeric cMet, Her3 and EGFR were analyzed in concentrations from 4.94 to 1200 nM in triplicates on a CM5 sensor chip at 37°C. For the dimeric antigen IGF1R a sensor chip C1 was used at 25°C, with concentrations of 2.7–400 nM, one of these as duplicate.

Simultaneous in-solution binding of all antigens to TriMAbs

TriMAbs were captured via α-human Fc on a C1-Chip. Four antigens were injected consecutively using two dual injects with a contact time of 180 s each. The antigen concentration was chosen for each antigen close to saturation (∼90%) as observed in the kinetics experiment. As control a second inject of the identical antigen did not raise response level, demonstrating equilibrium was reached (cMet: 1200 nM, EGFR: 1000 nM, Her3: 1000 nM and IGF1R: 400 nM). A temperature of 25°C was chosen to minimize dissociation.

Binding of FcγRIIIa to TriMAbs in presence of all antigens

EGFR was amine coupled on a C1 sensor chip. TriMAb/MAbs-binding EGFR were injected, followed by a dual inject of the remaining antigens (first inject: Mix Her3/cMet, second inject: IGF1R). The binding of FcγRIIIa was measured by a subsequent inject with 180 s association and 600 s dissociation phase at 25°C. Regeneration was performed with 15 mM NaOH.

Cooperative binding of TriMAbs to mixture of antigens on the chip surface

PentaHis antibody (Qiagen) was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip with high ligand density (15 000 RU). His-tagged IGF1R and His-tagged Fc chimera of cMet, EGFR and Her3 were captured either as single antigens or a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 mixture by volume. Single antigen concentrations were adjusted by a 1 : 3 dilution with buffer. MAbs and TriMAbs were injected as analytes (c = 30 nM) with an association phase of 180 s and a dissociation phase of 1800 s. To obtain faster dissociation and clear avidity effects the experiment was performed at 37°C. Regeneration: 10 mM glycine pH 2.0

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were carried out using an iTC200 from MicoCal Inc. (Northampton, MA, USA) at 25°C. To avoid buffer artifacts all protein samples were dialyzed against PBS at 4°C. For further reference purposes the calorimetric dilution effect of dialyzed buffer as well as every other particular titrant was evaluated in advance. Eighteen automatically defined injections of 2 µl over 5 s and a syringe stirring of 600 rpm were used as overall settings. While highest possible concentrations (15–38 µM) were used for the soluble receptor titrants in the syringe, 1.5–1.8 µM of the particular MAb in the mess cell were applied. Data analysis was performed with ‘Origin’ (supplied by Microcal Inc.). Data points were fitted to a theoretical titration curve, resulting in ΔH (binding enthalpy in kcal mol−1), KA (association constant) and n (number of binding sites per monomer). In consecutive injects of several titrants alterations in mess cell concentrations were corrected (for any further titrant) by defining end point concentrations of one titration as starting concentrations for the next titration.

Results

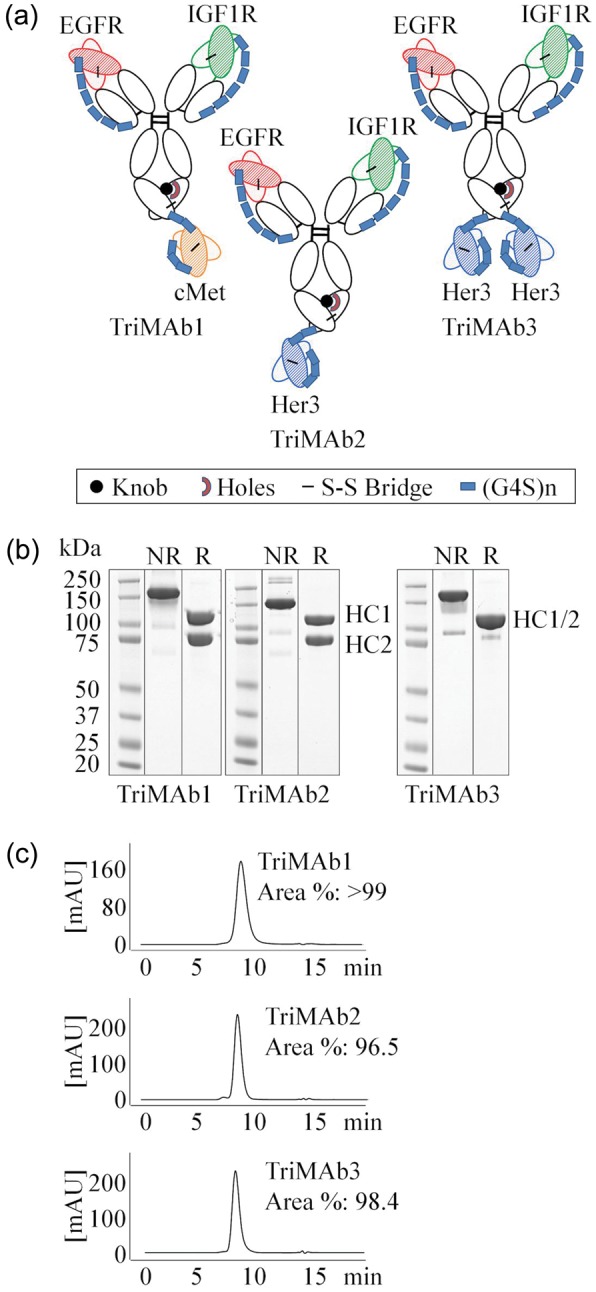

Generation of trispecific antibodies

We selected one TriMAb format which enabled monovalent binding to each antigen and one which was bivalent for Her3 (Fig. 1a). To this end, the knobs-into-holes technology was used to differentiate the IgG1 heavy chains (HCs) (Ridgway et al., 1996; Atwell et al., 1997). Light chain mispairing was prevented by employing the single chain Fab (scFab) and single chain Fv (scFv) technology (Fig. 1a). scFab and scFv formats have been described in the past (Kontermann, 2010). Antibodies were transiently expressed in HEK-293F and purified by standard Protein A and size-exclusion chromatography. Gel electrophoresis, analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy (Fig. 1b, c and data not shown) confirmed homogeneity greater than 95%.

Fig. 1.

Production of trispecific antibodies based on scFab and scFv. (a) Schematic presentation of trispecific antibodies. HCs are distinguished by knobs-into-hole technology. scFabs were constructed by VL-CL-(G4S)6-VH-CH1 fusion to the constant regions of human IgG1. scFv were fused with a (G4S)2 connector to the C-terminus of the HC in the order of VH-(G4S)3-VL. (b) Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of protein A and size-exclusion purified TriMAbs under non-reducing (NR) and reducing (R) conditions. (c) Analytical HPLC of TriMAbs. A colour version of this figure is available as supplementary data at PEDS online.

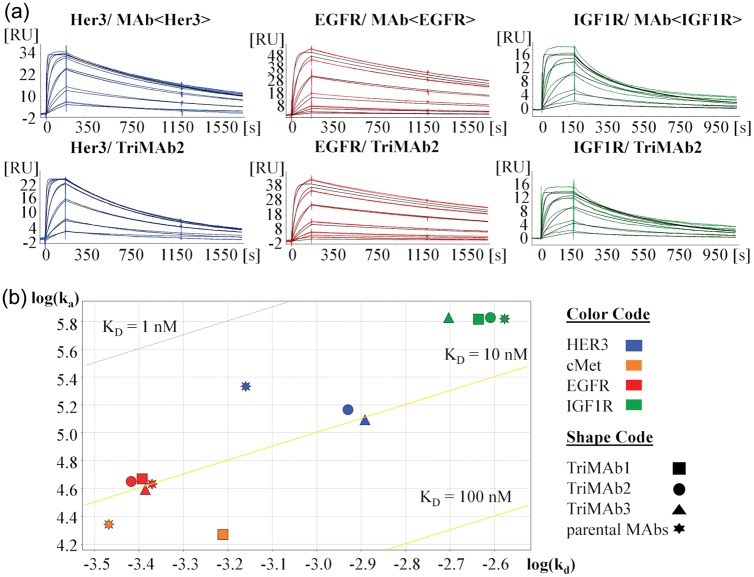

Kinetic characterization of single antigen binding to TriMAbs

For each of the four different antigens cMet, Her3, IGF1R and EGFR recognition by the TriMAbs1, 2 and 3 was compared with the corresponding parental antibodies using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). TriMAbs were captured on a sensor chip and the binding kinetics of the soluble receptors was measured using a concentration series for each antigen in separate runs. To verify that antigen binding was not impaired by the capture method, three different setups were examined. To this end, human specific antibodies against kappa light chain, the Fab moiety or the constant Fc were used for antibody capturing. Exemplary binding of one of the antigens (EGFR) showed only minimal changes in the kinetic constants (data not shown). For IGF1R the assay setup was modified to account for its homo-dimeric structure. To obtain monovalent binding, a C1 chip with very low ligand density and thus capture level of the antibodies was chosen (∼8 RU). In a control experiment it was demonstrated with the Fab fragment of the parental IgG1 antibody that the kd-rates of both are comparable under the selected conditions. Similar results were obtained in a reversed assay format with amine-coupled receptor and Fab fragment (data not shown). For quantitation of IGF1R binding kinetics the temperature was reduced to 25°C to obtain ka-rates within the instrument limitations, since the parental MAb<IGF1R> has a very high ka. Upon capturing of TriMAbs by Fc-specific antibodies, it was found that all TriMAbs were functional in binding each of the single antigens and moreover retained kinetic profiles comparable to that of their parental MAbs as exemplarily shown for TriMAb2 (Fig. 2a). To better visualize this and allow relative comparison of all three TriMAbs we chose to deconvolute kinetics in a log(ka)–log(kd) plot (Fig. 2b). Whereas the scFab moieties bound EGFR and IGF1R with virtually the same affinity as the parental MAbs, we found that the affinity of the scFv moieties for Her3 or cMet was slightly reduced by a factor of 2–3 (Table I). Slight deviation from Langmuir 1 : 1 fits (RI = 0) or exceeding of the theoretical Rmax observed in some cases was most likely due to small amounts of aggregates in the antigen batches used, but no difference between the parental and the TriMAbs was observed. Deviations from Langmuir 1 : 1 binding were most apparent for the IGF1R specificity, but are likely intrinsic to the antibody clone as a different control antibody binding the same epitope region did not show this phenomenon (data not shown). Thus, we could demonstrate that all TriMAbs have similar monospecific-binding properties like the corresponding MAbs.

Fig. 2.

(a) SPR sensorgrams (concentration series) of soluble receptor binding to parental MAb<Her3, EGFR, IGF1R> and TriMAb2. Sensorgrams were fitted to a Langmuir 1 : 1 model, RI = 0 (black lines). (b) Plot of the kinetic constants of TriMAb1, 2, 3 and their corresponding parental MAbs for binding soluble receptors Her3, cMet, EGFR and IGF1R, as measured by SPR. Diagonals depict iso-affinity lines. A colour version of this figure is available as supplementary data at PEDS online.

Table I.

Kinetic constants for binding of soluble receptors to parental MAb<Her3, EGFR, IGF1R> and TriMAbs

| Ligand | Analyte | ka (M−1s−1) | kd (s−1) | t(1/2) (min) | KD (M) | % SE (ka) (%) | % SE (kd) (%) | T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAb<Her3> | Her3 | 2.1E + 05 | 6.9E-04 | 16.7 | 3.2E-09 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 37 |

| TriMAb2 | Her3 | 1.5E + 05 | 1.2E-03 | 9.8 | 8.0E-09 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 37 |

| TriMAb3 | Her3 | 1.2E + 05 | 1.3E-03 | 9.0 | 1.0E-08 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 37 |

| Mab<cMet> | cMet | 2.2E + 04 | 3.4E-04 | 33.9 | 1.6E-08 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 37 |

| TriMAb1 | cMet | 1.9E + 04 | 6.1E-04 | 18.8 | 3.3E-08 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 37 |

| Mab<EGFR> | EGFR | 4.3E + 04 | 4.3E-04 | 27.1 | 1.0E-08 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 37 |

| TriMAb1 | EGFR | 4.7E + 04 | 4.0E-04 | 28.6 | 8.7E-09 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 37 |

| TriMAb2 | EGFR | 4.5E + 04 | 3.8E-04 | 30.2 | 8.5E-09 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 37 |

| TriMAb3 | EGFR | 3.9E + 04 | 4.1E-04 | 28.1 | 1.1E-08 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 37 |

| Mab<IGF1R> | IGF1R | 6.6E + 05 | 2.6E-03 | 4.4 | 4.0E-09 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 25 |

| TriMAb1 | IGF1R | 6.6E + 05 | 2.3E-03 | 5.0 | 3.5E-09 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 25 |

| TriMAb2 | IGF1R | 6.7E + 05 | 2.5E-03 | 4.7 | 3.7E-09 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 25 |

| TriMAb3 | IGF1R | 6.7E + 05 | 2.0E-03 | 5.8 | 3.0E-09 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 25 |

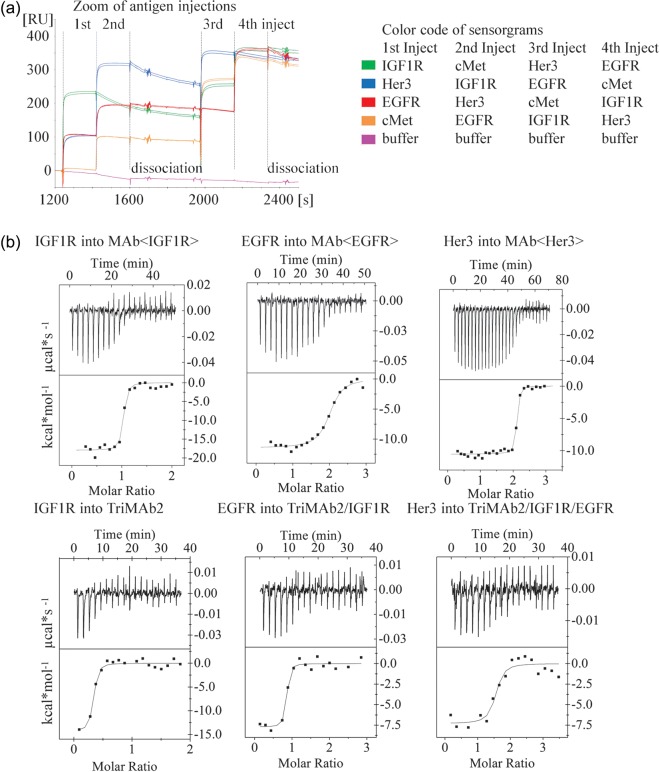

Simultaneous in-solution binding of all antigens to TriMAbs

Having shown that all antigen-binding moieties of the TriMAbs were per se functional, we next addressed the question whether several of the antigens could be bound simultaneously or whether steric hindrance between the large receptor molecules would impede this. Antibodies were captured via their Fc part and exposed to soluble receptor injected as analyte. Analyte concentrations were set to achieve near saturation (>90% of theoretical Rmax) of all MAb-binding sites during the ∼180 s association phase. Immediately following the association of the first receptor, the second receptor was injected in ‘dual injection mode’ leading to a ternary complex with the MAb. Finally, the third receptor was injected leading to a stepwise rise in the SPR signal (Fig. 3a). In several runs, the sequence of antigen injections was permutated as exemplary shown for TriMAb2 (Fig. 3a). At 25°C the concurrent dissociation of the first antigens during the course of these experiments was generally low and therefore a qualitative interpretation of the events was possible. TriMAbs 1, 2 and 3 showed subsequent binding of all three antigens (Table II). SPR signals were in all cases close to the theoretical Rmax, which indicated that binding of the second and third antigen was not significantly hindered by already bound antigen. This was also valid for TriMAb3 which can in theory bind a total of four receptor molecules (IGF1R, EGFR, 2× Her3). Only with IGF1R, which is a naturally cysteine-bridged homo-dimer, a slight effect on subsequent cMet binding was observed for TriMAb1. The findings have been summarized in a quantitative manner for all TriMAbs in Table II. It is of note that for homo-dimeric IGF1R the theoretical Rmax is between 50 and 100% since a significant portion of this antigen is bound bivalently by two neighboring TriMAb molecules at the chosen ligand density. In summary, we demonstrate that all TriMAbs can simultaneously bind to all antigens.

Fig. 3.

(a) Overlay of SPR sensorgrams showing simultaneous binding of EGFR, IGF1R and Her3 (plus cMet as negative control) to TriMAb2. TriMAb2 was captured onto the sensor chip and binding of antigens studied by four consecutive injects (with a technical lack phase after second inject) of soluble receptors, permutating the order in different runs. Each run is highlighted by a different color. (b) Heat of receptor binding to MAbs measured by ITC and fitted to a 1 : 1 binding event curve. Top panel: soluble receptors titrated into a solution of their corresponding parental MAb in three independent experiments. Bottom panel: the three receptors titrated one after the other into the same solution of TriMab2. The consecutive titrations are evaluated and depicted separately. A colour version of this figure is available as supplementary data at PEDS online.

Table II.

Quantification of receptor molecules simultaneously bound by TriMAbs

| TriMAb | First antigen bound (%) | Second antigen bound (%) | Third antigen bound (%) | Fourth antigen bound (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1R | cMet | Her3 | EGFR | |

| TriMAb1 | 73 | 73 | 0 | 90 |

| TriMAb2 | 72 | 0 | 89 | 108 |

| TriMAb3 | 69 | 0 | 88 | 82 |

| Her3 | IGF1R | EGFR | cMet | |

| TriMAb1 | 0 | 71 | 89 | 89 |

| TriMAb2 | 99 | 69 | 85 | 0 |

| TriMAb3 | 95 | 64 | 84 | 0 |

| EGFR | Her3 | cMet | IGF1R | |

| TriMAb1 | 97 | 0 | 97 | 61 |

| TriMAb2 | 97 | 90 | 0 | 71 |

| TriMAb3 | 97 | 88 | 0 | 49 |

| cMet | EGFR | IGF1R | Her3 | |

| TriMAb1 | 103 | 87 | 60.5 | 0 |

| TriMAb2 | 0 | 93 | 63 | 63 |

| TriMAb3 | 0 | 92 | 61 | 59 |

Hundred percent theoretical maximum is deducted from the known capture level of TriMAbs in this experiment, where response units are directly proportional to molecular weight. A second inject of the same receptor did not increase binding (not shown).

Antigen binding to TriMAbs in solution via ITC

SPR-binding experiments were complemented by ITC which yields a more direct measurement of the stoichiometry. TriMAb2 in solution was titrated consecutively with all three antigens, and compared with corresponding titrations of the parental MAbs. Fitting of the observed heat effect to 1 : 1 binding events confirmed the simultaneous binding of all three receptors to TriMAb2 (Fig. 3b). Binding enthalpies were similar to those of the parental MAbs and in the same range for all antigens. The dimeric IGF1R showed a molar ΔH which was approximately twice that of the other monomeric receptors.

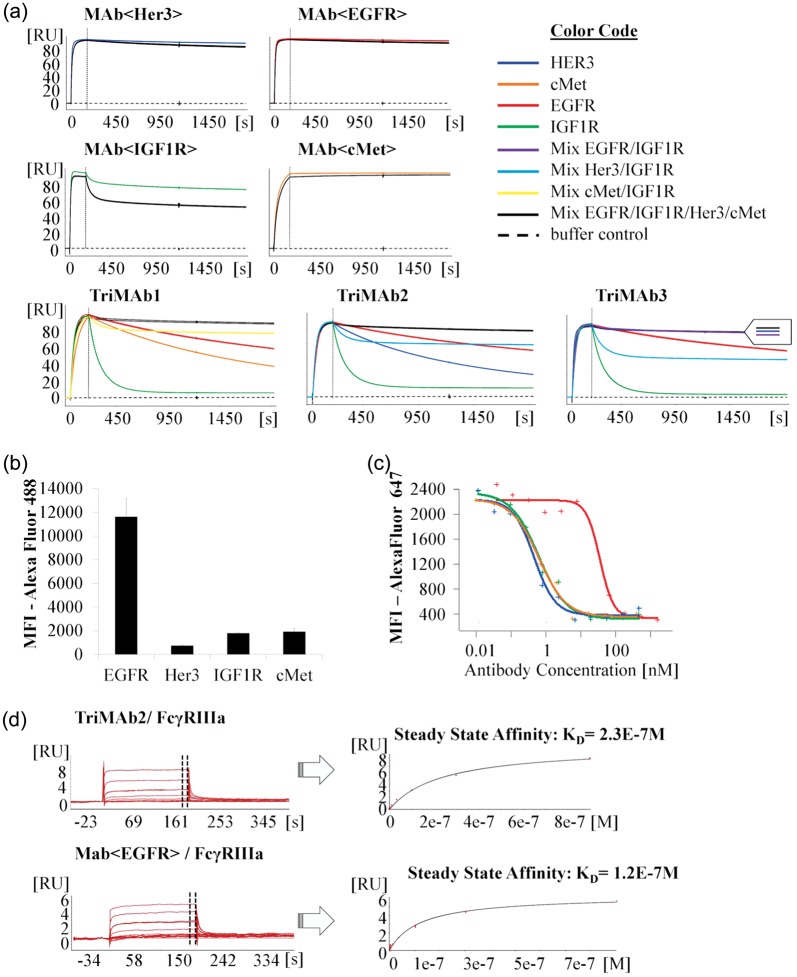

Cooperative binding of TriMAbs to a mixture of antigens

The aforementioned experiments confirmed that TriMAbs are able to bind all their antigens simultaneously. On cells the conformational freedom is much more restricted and antibody–antigen interactions are limited to certain geometries. To better approximate the steric situation on a cell surface, we looked at cooperative binding of soluble MAbs to different receptor molecules fixed on the sensor chip surface. Cooperative binding should be detectable as much lower dissociation rate of the MAb due to an avidity effect, compared with monovalent binding of only a single antigen. A roughly equimolar mixture of all receptor ectodomains (IGF1R, EGFR, Her3 and cMet) or binary mixtures (IGF1R and Her3, IGF1R and cMet) were captured onto the chip via their His tag by a PentaHis-antibody. As control, single antigens were captured on other flow cells. To demonstrate that the chosen antigen density was high enough to allow avid binding, each of the parental antibodies was analyzed as positive control. The parental IgG antibodies indeed bound bivalently to both their single antigen and the mixture of all antigens, as judged by the observed low kd-rates compared with previous experiments (Table I). TriMAbs 1 and 2 on the contrary are only able to bind monovalently to each antigen and showed marked dissociation (Fig. 4a) from single antigen surfaces. In contrast, when a mixture of the antigens was presented, the TriMAbs showed the expected avidity effect and a significantly decreased dissociation rate constant kd. These results imply cooperative binding of at least two antigens. We sought to confirm these findings on cells. A cell line expressing all four receptors, preferably with one of the receptors, which can mediate the avidity effect, in excess, was selected. BxPc3 cells were selected by their mRNA profile and receptor expression confirmed by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 4b). To a suspension of these cells, a dilution series containing a constant concentration of labeled bivalent MAb<IGF1R> and increasing amounts of unlabeled Fab or TriMAb molecules was added. The assumption was that TriMAbs will much more efficiently compete for IGF1R binding than the Fab<IGF1R> due to additional avidity mediated by the EGFR, Her3 or cMet specificity. As expected, a 56-fold reduction in the EC50 for the TriMAbs was found which implies avid binding on the cell surface (Fig. 4c). These data were in accordance with the findings on the sensor chip in which a strong avidity effect was observed for the EGFR/IGF1R mixture in contrast to IGF1R only. Finally, we obtained similar findings on cells, if Her3 or cMet were targeted instead of the IGF1R (Supplementary Fig. S1A and B). Thus, the artificial setup on a sensor chip can mimic effects found on living cells.

Fig. 4.

(a) SPR sensorgrams showing association and dissociation of parental MAbs and TriMAbs to chip surfaces coated with single antigens or mixtures of antigens in high density, as indicated by color code. Bivalent MAbs bind with avidity effect and dissociate slowly from either surface. TriMAbs dissociate slowly only from surfaces with mixtures of antigens, indicating cooperative binding to different antigens. (b) FACS-based analysis of cell surface receptor expression in BxPc-3 cells (mfi = mean fluorescence intensity). (c) FACS-based avidity assay in BxPc-3 cells (red = Fab<IGF1R>; green = TriMAb1; blue = TriMAb2 and orange = TriMAb3). (d) SPR sensorgrams of FcγRIIIa binding to TriMAb2 and parental MAb<EGFR> in the presence of antigens. FcγRIIIa association and dissociation was detected in a rising concentration series. Because of very fast ka- and kd-rates, KD was calculated from steady state. Averaged equilibrium response R(eq) at the indicated time point of the association phase were plotted against concentration of FcγRIIIa (fitted with steady-state model). A colour version of this figure is available as supplementary data at PEDS online.

Simultaneous in-solution binding of antigens and FcγRIIIa to TriMAbs

To examine whether simultaneous complexation of several antigens would impair binding of TriMAbs to FcγRIIIa, a soluble construct of the FcγRIIIa ectodomain was injected as the last analyte, subsequently to saturating the TriMAbs with all other antigens. For this, the first antigen, EGFR, was immobilized on the sensor chip and used to capture the TriMAbs, since capturing via anti-human Fc antibodies partially blocked the FcγRIIIa-binding site on the Fc part of the IgG MAbs. After complexation of all antigens, the TriMAbs still displayed high nanomolar affinity for FcγRIIIa (TriMAb1/2/3 KD: 222, 232, 254 nM) which is in the range of standard IgG1 antibodies (MAb<EGFR> KD: 120 nM) (Fig. 4d). Thus, according to the nomenclature of Triomabs (Trion) our TriMAbs could be called tetraspecific (Seimetz et al., 2010).

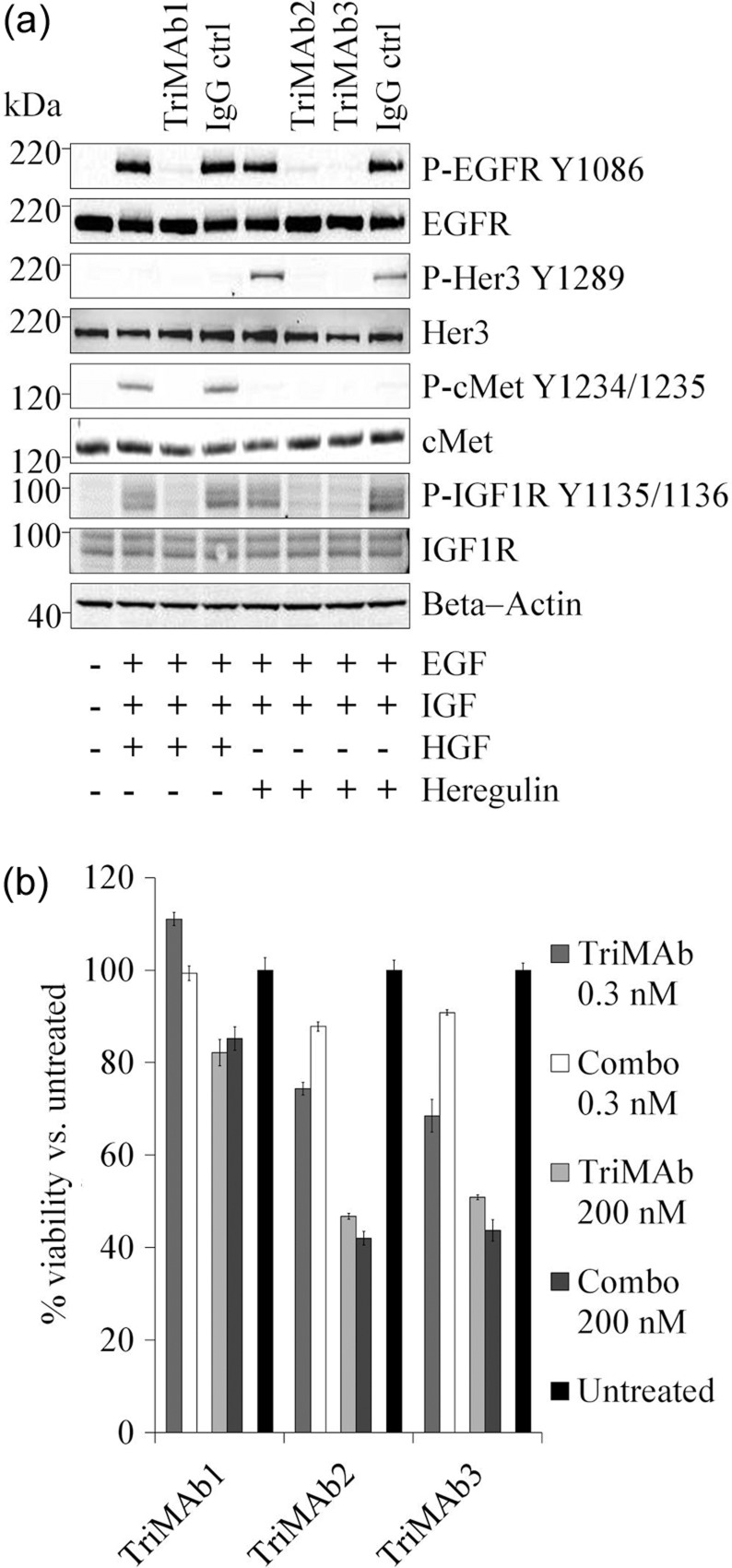

Inhibition of receptor signaling and cellular growth by TriMAbs

Cell surface expression and activation status of all receptors was confirmed in BxPc3 in the presence or absence of supplemented growth factors (Fig. 5a). Addition of TriMAbs inhibited ligand-dependent receptor phosphorylation. To further address the functional activity of TriMAbs a proliferation assay was performed and activity of individual antibodies or combinations was compared with TriMAb activity (Fig. 5b). We observed significant growth inhibitory effects for combined targeting of EGFR, IGF1R and Her3 but not for TriMAb 1 containing a cMet specificity. Neither of the single parental antibodies had significant effects on proliferation in BxPc3 (data not shown). In conclusion, TriMAbs were as efficacious as the combination of all three parental antibodies (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Functional analysis of TriMAbs in BxPc3. (a) Immunoblot analysis of receptor expression and phosphorylation in BxPc3. (b) Proliferation assay with TriMAbs in comparison to the relative combinations of the three parental antibodies. Percentage viability was evaluated versus controls (set to 100%). Presented is the mean of two independent experiments.

Discussion

We present here the generation of trispecific antibodies for cancer therapy. The chosen antibody scaffold admittedly poses some challenges with regard to production and characterization. Which titers and purity can be obtained in stable chinese hamster ovary production cell lines remains to be seen as this cannot be predicted from our results with transient expression in HEK-293F. Stability analysis of the generated TriMAbs revealed that TriMAb1 had a melting curve well above 60°C and displayed long-term stability at elevated temperatures (Supplementary Fig. S2A and B). The other two TriMAbs were less stable with partial unfolding already at 45°C. Since stable and less stable TriMAbs only differed in the Her3 scFv, clone specific variable region differences seem to have affected the stability of our TriMAbs. Such clonal variation is also observed for regular MAbs and does therefore not pose a special threat for further development of this antibody format.

The characterization of TriMAbs with regard to their binding and functional properties presents additional challenges in comparison to BiAbs. First and foremost, the analysis of antigen binding is more complex and the important question, whether such molecules indeed have the capacity to simultaneously bind to different tumor antigens has to be addressed for each combination individually. Our findings that simultaneous binding to three large extracellular domains of receptor tyrosine kinases is in principle feasible implies that there is a surprisingly high flexibility in the binding of multiple antigens. Nevertheless, simultaneous binding of three soluble target proteins certainly poses less steric constraints than simultaneous binding to three membrane anchored antigens on a living cell.

On the cell surface, lateral diffusion, steric hindrance by other proteins or variable antigen availability due to endocytosis or receptor shedding might impair accessibility. In order to more closely mimic cell membrane conditions, we developed an experimental approach in which different antigens are simultaneously bound to a chip surface. We challenged this artificial setup by comparison with a cell line expressing all receptors. In this cellular competition experiment we found a good correlation with the data obtained by SPR and could additionally demonstrate that our TriMAbs display avidity due to at least bispecific binding. This suggests that a mixture of antigens bound to the chip surface can serve as a surrogate setup for direct cell surface analysis.

Furthermore, we confirmed binding of FcγRIIIa ectodomain to the Fc part of TriMAbs. It is particularly interesting that the FcγRIIIa–Fc interaction was not only unimpaired by scFv fusions at the C-terminus of the HCs, but also tolerated the concomitant presence of all three antigens. Hence, it can be expected that TriMAbs retain their effector cell recruitment potential also in cellular assays.

Based on these findings, we propose a novel technical approach whereby a combination of SPR, ITC and cellular avidity assays quickly and accurately sheds light onto the binding properties of a chosen TriMAb combination; such data are of a quantitative nature when the first two methods are applied and of a semi-quantitative nature for the cellular assay setup. This novel approach can for instance support format optimization by permutation of the order of antigen-specificities on the Fab arms or on the HC fusion sides.

Interestingly, the presented TriMAbs did not exhibit agonistic activity as might have been expected from bringing different receptor tyrosine kinases in close proximity. This suggests that receptor cross-activation either requires a very specific spatial orientation of the interacting partners or that the receptors have to adopt an active conformation not compatible with TriMAb binding. From the perspective of therapeutic benefit and health care costs TriMAbs appear attractive, since we obtained similar functional activity with them as a single therapeutic agent as with a combination of three MAbs. However, other potential challenges that are outside the scope of this study, like their technical developability, potential immunogenicity and adverse effects, need to still be addressed before tri- or tetraspecific antibody formats can enter into clinical trials. In conclusion, a combined analysis of our data strongly supports the notion that TriMAbs present a powerful avenue to follow on the way to drugs which potently inhibit tumor and associated de novo escape mechanisms.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at PEDS online.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Schwaiger and I. Ioannidis for help in protein purification and analysis of obtained results. We thank P. Gimeson (GE Healthcare) for professional help with the analysis of ITC results. We thank M. Venturi and G. Kollmorgen for expert review of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Roche Diagnostic GmbH.

References

- An Z. Protein Cell. 2010;1:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0052-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwell S., Ridgway J.B., Wells J.A., et al. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;270:26–35. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno L., Jirillo A., Favaretto A. Curr. Drug Targets. 2011;12:922–933. doi: 10.2174/138945011795528958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossenmaier B., Dimoudis N., Friess T., et al. 2011. WO 2011/076683 http://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2011076683&recNum=1&maxRec=1&office=&prevFilter=&sortOption=&queryString=11076683&tab=PCT+Biblio .

- Chames P., Baty B. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2009a;12:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chames P., Baty D. MAbs. 2009b;1:539–547. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M.S., Billeci K., Young J., et al. 2007 US 2007/0092520 A1. [Google Scholar]

- Filpula D. Biomol. Eng. 2007;24:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A.W., Haluska P. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;10:1032–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes N.E., Lane H.A. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes N.E., MacDonald G. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamouzis M.V., Konstantinopoulos P.A., Papavassiliou A.G. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:709–717. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontermann R.E. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2010;12:176–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenkele K.P., Graus Y., Kopetzki E., et al. 2005 WO 2005/005635 A3 http://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2005005635&recNum=1&maxRec=1&office=&prevFilter=&sortOption=&queryString=WO05005635&tab=PCT+Biblio . [Google Scholar]

- Mansi L., Thiery-Vuillemin A., Nguyen T., et al. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2010;9:301–317. doi: 10.1517/14740330903530663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz S., Haas A.K., Daub K., et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8194–8199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018565108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen U.B., Huhalov A., et al. 2008. 31st San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposiumhttp://www.mindcull.com/data/no/sabcs-2008-san-antonio-breast-cancer-symposium/p:64/r:10/

- Nieri P., Donadio E., Rossi S., et al. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:753–779. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J.V. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay V., Allaf L., Wilding A.L., et al. Neoplasia. 2009;11:448–458. doi: 10.1593/neo.09230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivot X., Bedairia N., Thiery-Vuillemin A., et al. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:701–710. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328345ffa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway J.B., Presta L.G., Carter P., et al. Protein Eng. 1996;9:617–621. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopenian D.C., Akilesh S. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer G., Haber L., Crocker L.M., et al. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:472–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimetz D., Lindhofer H., et al. Canc. Treat. Rev. 2010;36:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur A., Lum L.G. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2010;12:340–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana P., Mossner E. 2011 WO 2006/082515 http://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2006082515&recNum=1&docAn=IB2006000238&queryString=FP:(WO06082515)&maxRec=1 . [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veeken J., Oliveira S., Schiffelers R.M., et al. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:748–760. doi: 10.2174/156800909789271495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieth M., Sutherland J.J., Robertson D.H., et al. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:839–846. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03477-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y., Sliwkowski M.X. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.