Abstract

Although various gene delivery techniques are available, their application in zebrafish cell cultures has not been extensively studied. Here, we report that nucleofection of zebrafish primary embryonic fibroblasts results in higher transfection efficiency in comparison to other non-viral gene delivery methods. The transfection was performed using green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene constructs of a different size. Greatest DNA uptake was obtained with 4.9-kb plasmid, resulting in 43% GFP positive cells. Nucleofection with 7.4-kb pH2B-GFP plasmid followed by geneticin (G418) selection was successfully used to establish a cell line expressing nuclear histone 2B-GFP fusion protein. Efficient transfection of zebrafish fibroblasts by nucleofection offers a non-viral technique of plasmid delivery and can be used to overexpress genes of interest in these cells.

Keywords: Fibroblasts, Primary cells, Transfection, Zebrafish

Introduction

Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) is an important vertebrate model organism for genetics, developmental biology, chemical biology and regeneration. Much of its popularity results from its utility as an in vivo model (Berghmans et al. 2005). The lack of robust methods to transfect zebrafish cell lines have hindered the application of biochemical and cell-based assays that are frequently used in mammalian studies. A variety of transfection methods have been developed in mammalian system including chemical (e.g., calcium phosphate coprecipitation), lipid-based methods, physical (e.g., electroporation) and viral (e.g., retrovirus) approaches (reviewed in Smith 2002). There are a few reports of zebrafish cell culture transfection. Electroporation has been applied in zebrafish embryonic stem (ES) cells to deliver a targeting construct for homologous recombination (Fan et al. 2006). Zebrafish liver cells have been reported to be transfected by lipofection (Chen et al. 2005). Lipid-based reagents have also been used for transfection of epithelial cell culture from another fish species, Xiphophorus xiphidium (Rambabu et al. 2005). A variety of transfection methods have been tested in the fish medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryonic stem (ES) cell lines, including electroporation, calcium phosphate co-precipitation, lipofection and commercial reagents FuGene and GeneJuice (Hong et al. 2004). Electroporation was identified as the most efficient method in this study. Given that many experiments require reproducible and efficient transfection, the existing approaches may not be sufficient for certain cell lines. Nucleofection is another electroporation-based technique, which has recently been developed. Various cell types have been reported to be successfully transfected using this technology, such as human lymphocytes, bovine chondrocytes and rat cardiomyocytes (Gresch et al. 2004). Here, we report an efficient transfection of primary zebrafish fibroblasts using nucleofection to achieve transient or stable expression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). In addition, we compare the transfection efficiency of nucleofection with other popular non-viral transfection methods in zebrafish fibroblasts.

Materials and methods

Primary zebrafish embryonic fibroblasts cell culture

To establish the primary cell culture, 200–300 zebrafish AB strain embryos at a 5–10 somite stage were dechorionated by 300 μg/ml protease (from Streptomyces griseus, Sigma P5147, St. Louis, Mo, USA) treatment, washed in PBS, disinfected with bleach (sodium hypochloride, Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA) diluted 1:400 in PBS for exactly 2 min, disintegrated with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA), and plated on a 25 cm2 Collagen I Biocoated flask (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were cultured in a medium composed of DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, high glucose, no sodium pyruvate, Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 15% FBS (Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 1% trout serum (SeaGrow, East Coast Biologics, Inc., North Berwick, ME, USA), 50 μg protein/ml of zebrafish embryo extract, 10 μg/ml bovine insulin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA), 50 ng/ml of bovine basic fibroblast growth factor (bbFGF, Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA), 100 U/ml Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 100 U/ml Ampicillin (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA). The medium was further enriched by adding 25 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (EGF, Invitrogen). After the second passage, cells were cultured in a medium containing all the above except for EGF and bbFGF. Primary zebrafish embryonic fibroblasts, ZEF1 and ZEF2, were maintained at 29°C and 5% CO2 for two and three months, respectively, before transfection.

Plasmids

Two different vectors were used for transfection. To generate a vector expressing cytoplasmic GFP, pCS2-EGFP (4.9-kb), enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene was cloned using a XbaI restriction site under the control of cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in pCS2 vector (Rupp et al. 1994). To create a vector that expresses a nuclear GFP and contains a neo resistance cassette, we cloned pGT-H2B (7.4-kb) as follows. EF1alpha: histon2B-GFP from vector pBOS (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was amplified by PCR with primers that were supplemented with AatII restriction sites ctg agg tcc aga cgt ccg tga ggc tcc ggt gcc and agt gcc acc tga cgt cta ag. The 2.7-kb PCR product was cloned into pGT-N28 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) using AatII site.

Transfection by nucleofection

For nucleofection of zebrafish fibroblasts, cells from two primary cultures ZEF1, ZEF2 and cell line AB9 (gift from L. Zon) were seeded and after 36-h harvested by incubation with 0.25% trypsin/0.1% EDTA. After centrifugation (200 × g for 10 min), 3 × 106 cells were resuspended in 100 μl T solution (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and mixed with 2 μg of plasmid DNA. The mixture was then transferred into a kit-provided cuvette and the cells were electroporated using the nucleofector device (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and program O-20. The optimal combination of a type solution and transfection program were identified after performing an optimization procedure according to the manufacturer’ instructions. Immediately after the electroporation, 500 μl of the prewarmed (29°C) culture medium were added into the cuvette, and then transferred into a culture medium in collagen I 10 cm biocoated plates. After 24-h, the plates were washed to remove the unattached cells and images were taken using a 10 × objective with a Zeiss microscope equipped with a UV lamp and Axiovision camera. Cells were then counted by two observers. The transfection efficiency was determined by the proportion of GFP positive cells to the total number of survived cells, whereas cell viability was assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion in comparison to the number of cells seeded without electroporation. A minimum of four fields were counted, each of them corresponded to at least 100 cells.

Other non-viral methods of cell transfection

We compared the optimized nucleofection method with other popular transfection techniques such as the non-liposomal multi-component transfecting reagent FuGene 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and the cationic lipid formulation Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). We transfected ZEF1 cells according to the manufacturers’ protocols. For transfection with FuGene 6, cells were seeded into collagen I biocoated 6-well plates, 8 × 104 cells per well to achieve 50–60% confluence after 24-h growth. Reagent-DNA complexes were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and at a 3:1 FuGene 6-DNA ratio, which we experimentally found to be the optimal ratio for zebrafish fibroblasts. The transfection efficiency and cell survival rate were analyzed 24-h later. To evaluate transformation with Lipofectamine 2000, ZEF1 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells per well into collagen I biocoated 6-well plates and then in 2 ml serum and antibiotics free medium to achieve 90–95% confluence. Lipid-DNA complexes prepared at a 5:1 ratio were experimentally determined to be the most favorable for zebrafish fibroblasts. Six hours post-transfection, the cells were thoroughly washed with antibiotic free medium. Transfection efficiency and survival rate were analyzed 24-h later in the way described above. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Results and discussion

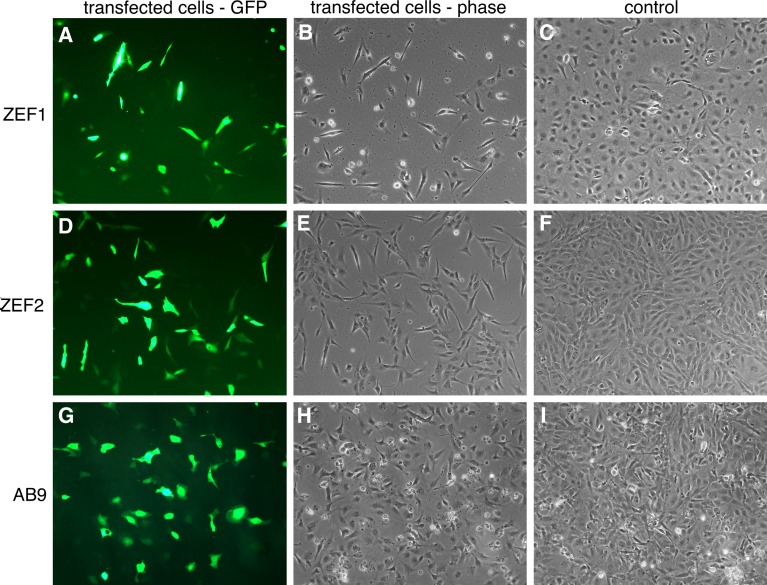

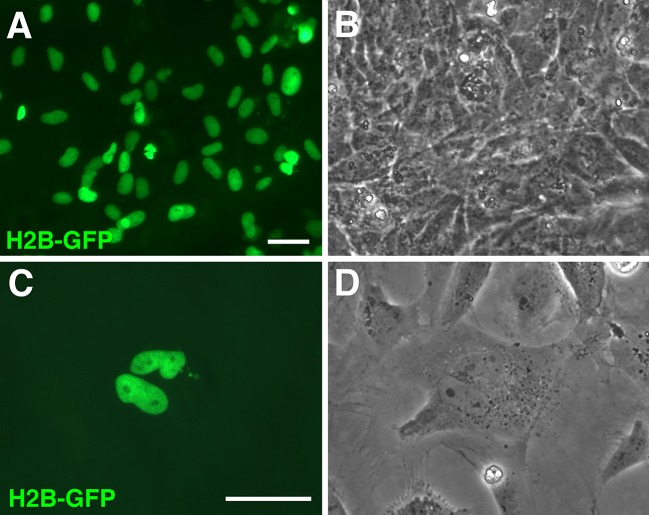

We have evaluated the nucleofector technology for the gene transfer into zebrafish primary embryonic fibroblasts and fibroblast cell line using pCS2-GFP plasmid. Quantitative assessment of the nucleofection efficiency by two observers revealed that the transfection of ZEF1 and ZEF2 cells resulted in 43 and 35% GFP-positive cells, respectively. The cell survival was 30 and 35% for both primary fibroblast cultures, respectively (Fig.1 A–F). When AB9 cells were nucleofected with program O-20, similar transfection efficiency of 35% GFP-positive cells was achieved, while the cell viability climbed up to 40% (Fig. 1G–I). The higher viability values obtained for AB9 cells might be explained by the fact that, in contrast to the heterogeneous population of primary cells, the AB9 cell line is a homogenous long-term selected cell culture. In all transfections, no morphological or functional differences between transfected and non-transfected cells were observed (Fig. 1). In addition, we aimed to generate a cell line that expresses a nuclear GFP. Nucleofection of ZEF1 cells with a linearized pH2B-GFP plasmid resulted in 30% efficient DNA uptake. To select for stable plasmid integration, the transfected cells were cultured for one month in G418 containing medium. After the selection, the vast majority of cells expressed H2B-GFP with a strict nuclear localization (Fig. 2). Thus, nucleofection technology can be used to establish stable transgenic cell lines in zebrafish.

Fig. 1.

Efficient transfection of zebrafish fibroblasts with pCS-GFP using nucleofection program O-20. (A–C) transfection of 2 × 106 primary cells ZEF1 resulted in 43% GFP-positive cells and 30% viability (A, B) as compared to the control cells that have been seeded without electroporation (C). (D–F) transfection of 4 × 106 primary cells ZEF2 resulted in 35% GFP-positive cells and 35% viability (D, E) as compared to the control cells (F). (G-I) transfection of 4 × 106 AB9 zebrafish fibroblast cell line resulted in 35% GFP-positive cells and 40% viability (G-H) as compared to control cells (I). Cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes. Images were taken 24-h after transfection using 10 × objective

Fig. 2.

ZEF1 cells transfected with pH2B-GFP plasmid using nucleofection program O-20. (A and C) Nuclear localization of H2B-GFP in transfected cells. (B and D) Images of transfected cells in phase contrast. (A, B) zebrafish fibroblast cell line with a stable integration of pH2B-GFP. (C, D) H2B-GFP visualizes cell divisions. Images were taken one month after nucleofection and G418 selection. Scale bars correspond to 50 μm

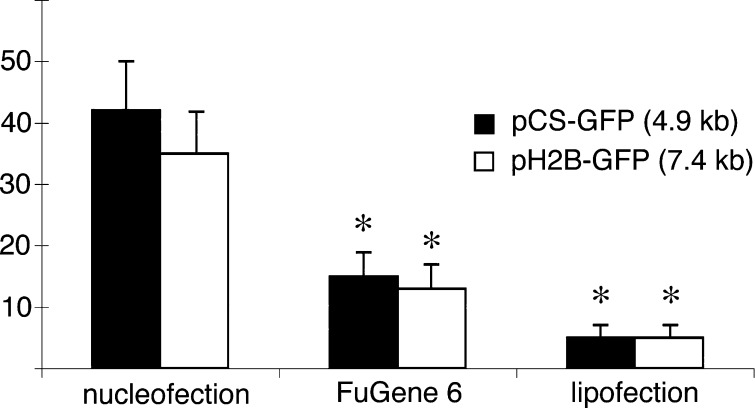

We compared the optimized nucleofection method with other popular non-viral transfection techniques, namely FuGene 6 and Lipofectamine 2000 using pCS2-GFP, pH2B-GFP. When ZEF1 cells were transfected with FuGene 6, the maximal uptake of GFP plasmid was achieved with a 3:1 reagent (μl)-to-DNA (μg) ratio that ranged from 12 to 15 % for the different size plasmids (Fig. 3). No morphological or functional differences between transfected and non-transfected cells were observed. Similar to our data, an efficiency of 11% was achieved in medaka MES1 cells with FuGene and the highest efficiency of above 30% was generated by electroporation (Hong et al. 2004). For lipofectamine transfection, we achieved the best results with reagent (μl)-to-DNA (μg) ratio 5:1 with efficiency rate of 5% and viability of 80% (Fig. 3). Thus, we found Lipofectamine 2000 complexes to be inefficient and toxic for zebrafish fibroblasts. The toxicity was determined based on the massive detachment of cells after 24-h incubation in the presence of the liposome reagent as recommended by the manufacturer’s instruction. As a result, we shortened the incubation time to 6-h, which resulted in 20% cell detachment and death as visualized by the viability assay. Although lipofection has successfully been used in many cell lines, it may have low efficiency in certain cell types due to intracellular barriers, such as poor endocytosis or poor endosome escape, and/or poor nuclear localization of the transfected DNA (Zabner et al. 1995). Such hard-to-lipofect cell types include primary human fibroblasts and mouse and medaka embryonic stem cells (Watanabe et al. 1997, Zauner et al. 1999, Hong et al. 2004). The nucleofector technology facilitates transfer of DNA from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, which might account for the improved transfection efficiency of zebrafish cell cullture. Indeed, nucleofection becomes very popular in stem cell research and in primary cell line studies (Siemen et al. 2005, Aluigi et al. 2006, Goffinet and Keppler, 2006). We speculate that nuclear import could be one of the most important limitations to successful gene transfer in primary zebrafish fibroblasts.

Fig. 3.

Differential transfection efficiency of zebrafish fibroblasts (ZEF1) using three optimized DNA delivery methods. The percentage of transfected cells was determined by cell counts 24-h post transfection. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of four individual experiments. * p value < 0.05 relative to nucleofection values

In summary, we developed a protocol for transfection of primary and long-term cultured zebrafish embryonic fibroblasts. We determined that the most efficient transfection of zebrafish fibroblasts is achieved by nucleofection with voltage and time parameters of program O-20 and solution T. The gene transfer by nucleofection led to transient or stable transfection. Nucleofection with two different plasmids resulted in greater uptake of DNA in comparison to FuGene or lipofectamine transfection. These findings are immediately useful for improving transfection efficiency of zebrafish fibroblasts and can be used to overexpress genes of interest in these cells. This method may be valuable for future applications in biomedical research involving zebrafish cell cultures.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Mark T. Keating in whose laboratory the project was initiated and supported. We thank J. Chan, M. Lutchman, S. Arab and I. Splawski for critical reading of the manuscript, F. Engel for discussions and M. Schebasta for sharing plasmids. The financial support was provided by an NIH/NHLBI award no. P50 HLO74734–02 and SCOR in Pediatric Heart Development and Disease. A.J. acknowledges the Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship for advanced researchers.

References

- Aluigi M, Fogli M, Curti A, Isidori A, Gruppioni E, Chiodoni C, Colombo MP, Versura P, D’Errico-Grigioni A, Ferri E, Baccarani M, Lemoli RM. Nucleofection is an efficient nonviral transfection technique for human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:454–461. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans S, Jette C, Langenau D, Hsu K, Stewart R, Look T, Kanki JP. Making waves in cancer research: new models in the zebrafish. Biotechniques. 2005;39:227–237. doi: 10.2144/05392RV02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, You YK, Chen JC, Huang TC, Kuo CM. Organization and promoter analysis of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) interferon gene. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:641–650. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Moon J, Crodian J, Collodi P. Homologous recombination in zebrafish ES cells. Transgenic Res. 2006;15:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s11248-005-3225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet C, Keppler OT. Efficient nonviral gene delivery into primary lymphocytes from rats and mice. Faseb J. 2006;20:500–502. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4651fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresch O, Engel FB, Nesic D, Tran TT, England HM, Hickman ES, Korner I, Gan L, Chen S, Castro-Obregon S, Hammermann R, Wolf J, Muller-Hartmann H, Nix M, Siebenkotten G, Kraus G, Lun K. New non-viral method for gene transfer into primary cells. Methods. 2004;33:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Chen S, Gui J, Schartl M. Retention of the developmental pluripotency in medaka embryonic stem cells after gene transfer and long-term drug selection for gene targeting in fish. Transgenic Res. 2004;13:41–50. doi: 10.1023/B:TRAG.0000017172.71391.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambabu KM, Rao SH, Rao NM. Efficient expression of transgenes in adult zebrafish by electroporation. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp RA, Snider L, Weintraub H. Xenopus embryos regulate the nuclear localization of XMyoD. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1311–1323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemen H, Nix M, Endl E, Koch P, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Brustle O. Nucleofection of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:378–383. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR. Gene transfer in higher animals: theoretical considerations and key concepts. J Biotechnol. 2002;99:1–22. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Shirayoshi Y, Koshimizu U, Hashimoto S, Yonehara S, Eguchi Y, Tsujimoto Y, Nakatsuji N. Gene transfection of mouse primordial germ cells in vitro and analysis of their survival and growth control. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230:76–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabner J, Fasbender AJ, Moninger T, Poellinger KA, Welsh MJ. Cellular and molecular barriers to gene transfer by a cationic lipid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18997–19007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauner W, Brunner S, Buschle M, Ogris M, Wagner E. Differential behaviour of lipid based and polycation based gene transfer systems in transfecting primary human fibroblasts: a potential role of polylysine in nuclear transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1428:57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]