Abstract

The effect of two culture configurations (single collagen gel and double collagen gel) and of two hormones (insulin and glucagon) on the differentiated status and the intracellular nucleotide pools of primary porcine hepatocytes was investigated. The objective was to analyze and monitor the current state of differentiation supported by the two culture modes using intracellular nucleotide analysis. Specific intracellular nucleotide ratios, namely the nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) and the uridine (U) ratio were shown to consistently reflect the state of dedifferentiation status of the primary cells in culture affected by the presence of the two hormones insulin and glucagon. Continuous dedifferentiation of the cells was monitored in parallel by the reduction of the secretion of albumin, and changes in UDP-activated hexoses and UDP-glucuronate. The presence of insulin maintained the differentiated status of hepatocytes for more than 12 days when cultivated under double gel conditions whereas glucagon was less effective. In contrast, cells cultivated in a single gel matrix immediately started to dedifferentiate upon seeding. NTP and U ratios were shown to be more sensitive for monitoring dedifferentiation in culture than the albumin secretion. Their use allowed the generation of an easily applicable NTP–U plot in order to give a direct graphical representation of the current differentiation status of the cultured cells. Moreover, the transition from functional and differentiated hepatocytes to dedifferentiated fibroblasts could be determined earlier by the nucleotide ratios compared to the conventional method of monitoring the albumin secretion rate.

Keywords: Hepatocytes, Collagen gel, Differentiation, Albumin, Nucleotide ratio

Introduction

Hepatocytes are the main cell type in liver. Primary hepatocytes attach to and spread on collagen and fibronectin, which are commonly used in culture systems to generate cellular scaffolds. The presence of extracellular matrix components can enhance the function and prolong the retention of differentiation markers in cultured hepatocytes. Cell adhesion to matrix scaffolds is necessary for cells to metabolize, survive or proliferate (Boudreau et al. 1995; Fang et al. 1996; Frisch and Francis 1994; Meredith et al. 1993; Re et al. 1994; Zhu et al. 1996). A large number of liver cell culture techniques have been developed to promote cell organization with the aim of providing conditions similar to in vivo conditions Cultivation on microcarriers (Demetriou et al. 1986), in the extra-capillary space of a multi-bundle hollow fibre membrane network (Gerlach et al. 1994), within a non-woven fabric mesh (Flendrig et al. 1997), co-culture with non-parenchymal cells in an extracellular matrix environment (Bucher et al. 1990; Bader et al. 1995; Yagi et al. 1998; Tilles et al. 2001), cultivation of primary hepatocytes in spheroids (Tobe et al. 1992; Kobayashi et al. 1994) or use of the so-called sandwich model (Dunn et al. 1989; 1991) have been reported to improve organization similar to the micro-architecture of hepatocyte monolayers found in vivo and of extending the presence of differentiation markers.

Albumin is a protein exclusively produced in hepatocytes. It is readily measurable in blood at concentrations of 30–50 g l−1 in healthy organisms (Rothschild et al. 1988) and it is commonly used as liver function marker. Clinical relevance is pronounced in chronic liver failure (Annoni et al. 1990) compared with acute liver failure. This clinical relevance has an in vitro parallel where albumin is a widely used parameter for tracking the gradual loss of the differentiated hepatocyte phenotype (Dunn et al. 1989, 1991; Itoh et al. 1994; Ranucci et al. 2000). This progressive loss of differentiated function is usually associated with a concomitant progressive decrease in albumin synthetic activity. The gradual diminution in albumin synthesis has been attributed to regulation by monokines, especially interleukin-6 (Koj et al. 1984; Gauldie et al. 1987; Andus et al. 1988; Castell et al. 1991). The reduction of albumin synthesis can be reduced by dexamethasone (Itoh et al. 1994).

Nucleotides are involved in a number of cellular processes and have widespread regulatory potential (Atkinson 1977). They participate as substrates, products, effectors or energy donors in many cellular reactions. Additionally, fluctuations in pool size can produce alterations in transport processes, macromolecular synthesis and cell growth. Some evidence has been reported, that the pool size of ATP, the adenylate energy charge (AEC) or the pool size of UTP, influence or correlate with the cell cycle (Rapaport et al. 1979), react to the stimulation of cells by serum (Grummt et al. 1977) or colchicines (Chou et al. 1984) and are involved in growth control (Murphree et al. 1974).

In previous experiments we have shown that the growth cycle of mammalian cell lines can be characterized by two particular nucleotide ratios; the Nucleoside Triphosphate (NTP) and the Uridine (U) ratio (Ryll and Wagner 1992). Both parameters have been used to monitor cell cultures. Variation in the U ratio, which is calculated by dividing the UTP concentration by the concentration of UDPGNAc (sum of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine) is mainly the result of an increase in the UDPGNAc pool (Ryll and Wagner 1992). A change in the U ratio has been shown to affect the N-glycan complexity of glycoproteins (Gawlitzek et al. 1998). Other studies revealed that an increase in the UDPGNAc pool can be the result of ammonium uptake which accumulates in cell cultures due to cellular metabolism and thermal degradation of glutamine (Gawlitzek et al. 1999; Valley et al. 1999; Ryll et al. 1994).

In addition, nucleotides are involved in liver-specific metabolic pathways. UDP-activated hexoses play an important role in specific hepatic functions. For example, activated glucose is involved in the formation of glycogen (Carabaza et al. 1986) and UDP-glucuronate is important for the cytochrome P450-mediated hepatic detoxification by increasing the water solubility of metabolites, thus facilitating their excretion (Ekberg et al. 1995). Therefore, the pool size of nucleotide-activated hexoses could potentially serve as an indicator for the differentiation status of hepatocytes in culture.

In this paper we present the application of nucleotide parameters in the monitoring of the differentiation status of primary porcine hepatocytes cultivated in sandwich and single collagen gel layer configurations.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Unless indicated otherwise, all chemicals used were of highest grade and purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany) or Sigma Chemical Company (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany).

Porcine hepatocyte isolation

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from freshly hepectomized 6–8 weeks old female pigs of the German land race of around 15 kg weight which were bred at the Institute for Animal Science and Animal Behavior (Mariensee, Germany) of the Federal Agricultural Research Center (Braunschweig, Germany). One day was given for the animals to soothe before hepectomy. After preparation according to the protocol published earlier (Bader et al. 2000; De Bartolo et al. 2000) the cannulized liver placed in ice-cold Ringer lactate was transferred into the perfusion vessel and immediately perfused with buffer I (consisting of 142 mmol l−1 NaCl, 6.7 mmol l−1 KCl, 10 mmol l−1 HEPES and 0.25 mmol l−1 EGTA, pH 7.2, 37°C) at a rate of 80 ml min−1. Buffer I was then removed and replaced by buffer II (buffer I without EGTA, 37°C). Finally, 200 ml buffer III (buffer II but with 66 mmol l−1 NaCl, 4.8 mmol l−1 CaCl2) containing 0.13 U ml−1 collagenase IV (307 FALGPA hydrolysis units per mg solid, Charge 5446862, Sigma from Clostridium histolyticum) were recirculated for 30 min until the liver disintegrated. Cells were liberated in ice-cold buffer and resuspended twice after sedimentation, as described previously (Bader et al. 1997).

Hepatocyte culture

Hepatocytes were first cultivated in Williams E medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) at 37°C, 90% humidity and 10% CO2 in an incubator (Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) and then transferred to 20 cm2 culture dishes (Integra, Bad Homburg, Germany) filled with ZKT-1 medium (custom-made by Sigma Chemie, Deisenhofen, Germany, Cat. No. I-99003). This medium is based on a 1:1 mixture of IMDM and F12 without HEPES and enriched with 2.2 g l−1 NaHCO3, 0.08 g l−1 alanine, 0.05 g l−1 arginine, 0.015 g l−1 asparagine, 0.292 g l−1 glutamine, 0.045 g l−1 glycine, 0.03 g l−1 histidine, 0.06 g l−1 proline, 0.06 g l−1 trypthophan, 1.8 g l−1 glucose, 0.008 g l−1 ciprofloxacin lactate (Ciprobay 200, Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), 0.001 g l−1 prednisolone hydrochloride (Solu Decortin, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 5% FCS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Either 20 IE l−1 insulin (Hoechst, Frankfurt, Germany) or 8 mg l−1 glucagonhydrochloride (Novo Nordisk A/S, Gentofte, Denmark) were used to adjust glycolytic or gluconeogenetic metabolic behavior. The culture plate surface was precoated with rat tail collagen Type I according to the method of Elsdale and Bard (1972). Five milliliter of precooled collagen solubilized in 10 times concentrated culture medium were used for polymerization onto the culture surface. 3 × 106 cells taken immediately after isolation with a viability higher than 80% were used for inoculation and incubated for 1 h to adhere to the surface. Subsequently, 4 ml culture medium were added and the cells were further incubated (SG cultivation mode, non-sandwich mode). Twenty four hours later the hepatocytes have formed polyhedra morphology. After confluence, corresponding to 5 × 106 cells, the culture medium was removed and the cells were overlaid by 1 ml collagen solubilized in 10 times concentrated culture medium. The collagen polymerized for 30 min in an incubator and finally additional 4 ml culture medium were added (DG cultivation mode, sandwich mode). Two days later, the cells have formed a liver-like morphology with cells of polygonal shape. This time was set to zero in all experiments. Every 2 days, the culture supernatant was replaced by fresh nutrient medium and the respective metabolic parameters were analyzed.

Analysis of cell culture

The total cell number of isolated cells was counted from two independent samples by means of a hemocytometer. Viable cell number was determined by the trypan blue exclusion method (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Glucose and lactate concentrations were determined using a YSI-Glucose/Lactate analyzer (Model 2000, Yellow Springs Instruments, OH, USA). Free amino acids were quantified by RP-HPLC after precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA, Serva Feinbiochemica, Heidelberg, Germany) as described by Larsen and West (1981). The NH3 concentration in culture samples was determined using a gas-sensitive ammonia electrode (Ingold Messtechnik AG, Urdorf, Switzerland) in duplicate. Urea concentrations were determined by colorimetric assay based on the Berthelot reaction (Chaney and Marbach 1962) using the kinetic enzymatic urease method (urea amidohydrolase, EC 3.5.1.5) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Albumin concentration was estimated using an ELISA previously described (Inaba et al. 1988; Dunn et al. 1989) with the modification that antibodies against pig albumin and pig albumin were used (both from ICN Pharmaceuticals, Bryan, OH, USA). Chromatographically purified albumin and a monoclonal antibody against albumin were purchased from Cappel (Durham, NC, USA). The whole procedure was described previously (De Bartolo et al. 2000). Quantification of intracellular nucleotides, UDP-GNAc and UDP-Hex was performed by IP-RP-HPLC after perchloric acid extraction of the cells in duplicate as described in detail previously (Ryll and Wagner 1991). Nucleotide ratios were quantified as follows and as previously described in detail (Ryll and Wagner 1992): AEC = [ATP + 0.5 ADP]/[ATP + ADP + AMP], NTP = (ATP + GTP)/(UTP + CTP), U = UP/UDPGNAc, NTP/U = UDPGNAc (ATP + GTP)/UTP (UTP + CTP). Standard deviation of the calculated cell specific UDPGNAc content, AEC, NTP and U values was always below 0.4 (UDPGNAc, AEC) and 0.1 (NTP, U).

Determination of the liquid volume of the matrix

For estimation of the liquid volume of the collagen matrix the cell culture supernatant was removed after cultivation and 200 μl PCA were added to the matrix. The denaturated collagen was harvested with a cell scraper and centrifuged at 5,000 g for 3 min. The liquid volume of the matrix was determined by volumetric measurement of the supernatant minus 200 μl PCA. This volume has to be considered by calculating cell specific rates.

Results

Albumin secretion

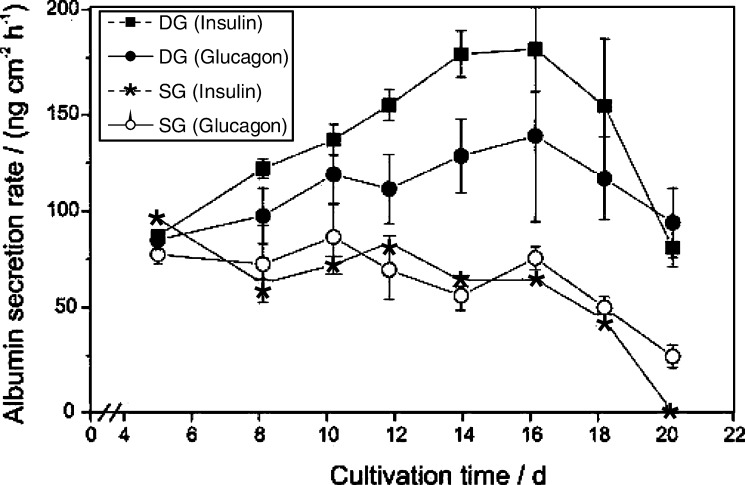

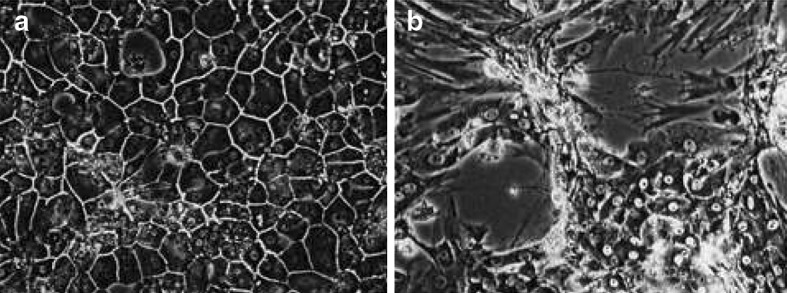

Freshly isolated primary pig hepatocytes were seeded and cultivated in SG and DG cultivation mode for 20 days. Medium was changed according to the specific requirements of the cells as controlled daily by the glucose (> 0.5 g l−1), lactate and amino acid concentrations of the culture supernatant. Eight experiments were run in parallel under glycolytic (insulin-supplemented) and gluconeogenetic (glucagon-supplemented) metabolic conditions, respectively. After 2 days four glycolytic and four gluconeogenetic cultures were coated with the second collagen gel (n = 4 for each of the four final conditions). The continuous dedifferentiation of the primary hepatocytes was monitored by the reduction of the albumin secretion rate (Fig. 1). All cultures achieved an albumin secretion rate of 78–96 ng cm−2 h−1 on day 5. Cells cultured in single gel showed a relatively constant secretion rate of 70–80 ng cm−2 h−1 up to day 16 and then a rapid decline to 0–26 ng cm−2 h−1. In contrast, cells grown in double gel mode were characterized by a constant increase in the albumin secretion rate up to 178 ng cm−2 h−1 on day 16 followed by a decline to 80–98 ng cm−2 h−1 at the end of the culture on day 20. Hormones substantially modified the albumin secretion rate. The presence of insulin revealed a 1.3-fold higher rate under DG cultivation conditions compared to glucagon. Moreover, cells cultivated under SG cultivation conditions did not significantly respond to hormones with respect to albumin secretion since no difference between insulin and glucagon treatment could be observed. However, a reduction of the cellular UDP-GlcUA content from 8 to 2 fmol was observed for primary porcine hepatocytes cultured under the same conditions in the presence of insulin (Fig. 3b). The dedifferentiation process was accompanied by a breakdown of the bile canaliculi and a transformation of the polygonal to a fibroblastic cell shape (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the albumin secretion rate of primary porcine hepatocytes grown in non-sandwich (SG, single gel) and sandwich (DD, double gel) mode in the presence of insulin or glucagon (n = 4)

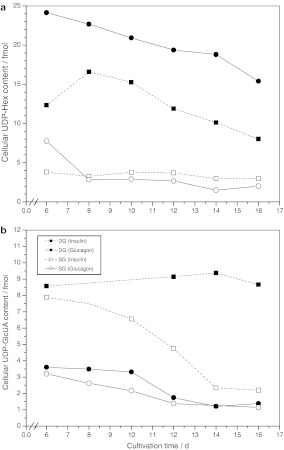

Fig. 3.

Progress of the cellular UDP-hexose pools (a) and the UDP-glucuronate content (b) of porcine hepatocytes grown under DG and SG conditions and supplemented with different hormones (n = 2)

Fig. 2.

Cells of primary porcine hepatocytes after 14 days of cultivation under sandwich (double gel, a) and non-sandwich (singel gel, b) configuration. The DG mode supported the formation of bile canaliculi and polygonal cells whereas undifferentiated fibroblastic cells were gown up under SG cultivation

UDP-activated sugars

Drastic differences in the intracellular UDP-Hex pool were found for hepatocytes cultivated under DG and SG mode (Fig. 3a). An intracellular UDP-Hex pool of up to 22 fmol per cell was reached on day 8 in DG cultures supplemented with glucagon compared to an average content of 3 fmol in SG cultures. Moreover, the intracellular UDP-Hex content in DG cultures was affected by hormones. A 2-fold higher content was found in hepatocyte cultures supplemented with glucagon compared to insulin supplementation. The intracellular UDP-GlcUA content was also affected by the culture conditions (Fig. 3b). Glucagon-supplemented DG and SG cultures showed a cellular UDP-GlcUA content of 3.5 fmol during the first 10 days of the cultures, which immediately reduced to 1.5 fmol per cell within the next 2 days and maintained this value up to day 16. In contrast, the presence of insulin resulted in a cellular UDP-GlcUA content of up to 8.5 fmol. However, DG-cultivated hepatocytes could maintain their cellular level over the 16 days period whereas SG-cultivated cells constantly reduced their cellular UDP-GlcUA level to 2.5 fmol following day 8.

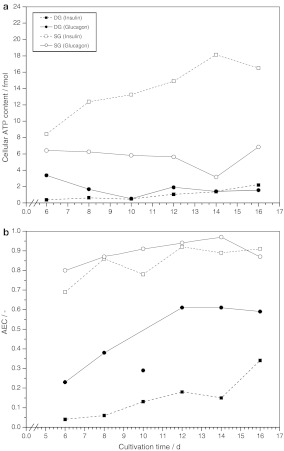

Nucleotide ratios

The cellular ATP content elucidated a substantial difference between SG and DG cultures (Fig. 4a). Cells grown under DG conditions showed a low cell specific ATP content of only 0.5–3 fmol when stimulated with insulin or glucagon. In contrast, single gel cultivation drastically influenced porcine hepatocytes to increase the ATP pool. SG cultures treated with insulin accumulated up to 18 fmol ATP per cell whereas stimulation with glucagon resulted in a cellular ATP content of 6 fmol. This dramatic difference in the pool size of ATP between cell cultures in DG and SG mode resulted in different AEC values (Fig. 4b). A high AEC above 0.7 was determined for cells growing under SG conditions whereas a low AEC between 0.05 and 0.65 was found for the respective cells in DG mode. Interestingly, the presence of glucagon led to a 2-fold increase of the AEC in DG cells due to a higher ADP content compared to the respective cells grown under the influence of insulin. In particular, AEC of cells growing in DG mode continuously increased indicating a continuous but slow dedifferentiation, which normally occurs in vitro but which could not be monitored by albumin secretion during cultivation as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 4.

Progress of the cellular ATP content (a) and the adenylate energy charge (b) of porcine hepatocytes grown under DG and SG conditions and supplemented with different hormones (n = 2)

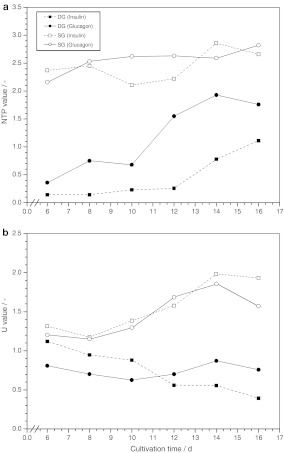

NTP and U values have been shown to be useful in characterizing the physiological state of cell cultures (Ryll and Wagner 1992). With respect to these parameters, significant differences between DG and SG cultivated porcine hepatocytes could be demonstrated (Fig. 5a). High NTP values, that maintained constant between 2.1 and 2.9 during the whole progress of cultivation, were found for cells cultivated under single gel conditions compared to values of 0.1 and 1.9 for cells cultivated in double gel mode. Interestingly, DG-cultivated cells showed a constant low NTP value during the first 10–12 days of cultivation followed by an increase in the NTP value until the end of cultivation which started 4 days earlier than the decrease of albumin secretion rate during this cultivation phase (Fig. 1). In contrast to SG-cultivated cells, significant differences in the NTP values were observed for DG-cultivated cells grown under the influence of insulin and glucagon (Fig. 5a). The presence of glucagon in DG cultures resulted in up to 4 times higher NTP after day 12 of cultivation compared to the respective insulin-supplemented culture. Moreover, the distinct change of the culture, indicated by an increase in the NTP value, occurred 2 days earlier at day 10 compared to the respective culture under the influence of insulin. The U value, which was reported to show an inversed behavior during the growth of continuous cell lines (Ryll and Wagner 1992), did not exactly correlate to the NTP value (Fig. 5b). Particularly, the U values determined for porcine hepatocytes grown under SG mode showed comparably low U values between 1.2 and 1.4 during the first 10 days of cultivation followed by an increase up to 2.0 for the rest of the cultivation. In contrast, the respective U values for cells grown under DG conditions did not show such an increase. However, insulin-supplemented cells grown under DG conditions continuously reduced their U values during the cultivation from 1.1 to 0.5 whereas the respective glucagon-supplemented cells showed constant values between 0.7 and 0.9.

Fig. 5.

Progress of the NTP (a) and U (b) value of porcine hepatocytes grown under DG and SG conditions and supplemented with different hormones (n = 2)

The nearly inverse behavior of NTP and U value of permanent cell lines in culture led to the combination of both values within the NTP/U value (Ryll and Wagner 1992). The combined ratio intensifies the sensitivity of the nucleotide ratio tool for characterizing the growth phases. The initiation of dedifferentiation of the primary porcine hepatocytes cultivated under differentiation-supporting DG conditions on day 10 and 12 for glucagon and insulin-supplemented cultures, respectively, is more clearly and earlier indicated by the drastically increasing NTP/U value (Fig. 6) than monitored by the albumin secretion and accumulation (Fig. 1) or by microscopic control. The respective cells grown under SG conditions showed complete different NTP/U values suggesting a different physiological state. Glucagon-supplemented conditions resulted in higher NTP/U values compared to insulin-supplemented cultures. This similarity for SG and DG-cultivated primary porcine hepatocytes correlates with the lower albumin secretion rate of glucagon-supplemented cells shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 6.

Progress of the NTP/U value of porcine hepatocytes grown under DG and SG conditions and supplemented with different hormones (n = 2)

Discussion

Specific metabolic changes are associated with differentiation and dedifferentiation of hepatocytes in culture. Using double gel and single gel configurations such changes were investigated with primary porcine hepatocytes freshly isolated from piglets. By using intracellular nucleotide analysis different physiological states could be characterized which may correlate with different states of dedifferentiation.

Albumin secretion

Albumin has widespread physiological importance as transport protein and osmoregulator in mammals. It is secreted into the blood and formed in the liver, where albumin is a characteristic indicator of functional and viable hepatocytes. Its secretion is used to monitor the differentiation status of functional hepatocytes under different culture conditions using sandwich technology. Cells grown in double gel configuration showed an increase in the albumin secretion rate. A maximum of 178 ng cm−2 h−1 was achieved corresponding to a cell specific productivity of 17 pg d−1 calculated on the basis that 5 × 106 cells formed a confluent monolayer in culture dishes of 20 cm2 surface. Hence, the cell-specific albumin secretion rate of porcine hepatocytes cultured in dishes was lower than reported for the respective cells cultivated in an in vivo-like microenvironment supported by a flat membrane bioreactor (De Bartolo et al. 2000) and the 30 pg d−1 secreted by primary rat hepatocytes (Kim et al. 2000). The maximum productivity of the hepatocytes grown under DG conditions was up to 2.6-fold more compared to those cells grown under single gel mode where the secretion potential could be maintained at a nearly constant level of 70 ng cm−2 h−1 for 16 days. In contrast, Dunn et al. (1991) reported a complete breakdown of the albumin synthesis already after one week of cultivation in SG mode using rat hepatocytes. Moreover, primary porcine hepatocytes responded differently to the presence of hormones when cultivated under SG and DG conditions. A 23% reduced albumin secretion rate of glucagon-treated, double gel-cultivated cells compared to the respective cultivation in the presence of insulin was found. In contrast, no significant influence of the hormones was found for cells grown under SG conditions when looking at albumin secretion. In addition, cells cultivated under SG conditions lost their polarity whereas it is maintained under DG cultivation conditions. This suggests that primary hepatocytes only respond to hormones when the differentiated status is maintained indicating accumulation of albumin as one reliable indicator for differentiation. However, one disadvantage of the accumulation of metabolites as a signal of differentiation is the sustainability of the signal which makes this tool slowly and insensitive to show rapid changing cellular events.

UDP-activated sugars

UDP-Glc is the dominant UDP-activated hexose in liver. Besides its central role as precursor molecule for glycogen synthesis, it is oxidized to form UDP-GlcUA, which is the central component of the major detoxification route in mammals characterized by the conjugation of toxic compounds with glucuronic acid (Miners and Mackenzie 1991). Conjugation with glucuronic acid makes the molecules more water soluble and thus facilitates excretion. The excretion of glucuronidated compounds from the cell is mediated by organic-anion transport proteins localized in the plasma membrane (Oude Elferink and Jansen 1994). DG-cultured hepatocytes maintained their differentiated status expressed as a high cellular UDP-GlcUA content of 9 fmol for more than 16 days (Fig. 3b) when stimulated with insulin, while UDP-GlcUA levels decreased in glucagon treated DG cultures from 4 fmol to 1.5 fmol after day 10. Also SG-cultured hepatocytes showed a high UDP-GlcUA content of about 8 fmol at the beginning of cultivation when treated with insulin, compared to glucagon treated SG cultures. This indicated that even SG cultivated hepatocytes maintained a low level of differentiation in the beginning of the experiments (day 6) as they were clearly able to respond to insulin stimulation. However, SG-cultivated hepatocytes continuously lost this ability from the beginning and did not respond to insulin after 14 days. This effect could not be observed when looking at albumin secretion. Therefore, we conclude that primary porcine hepatocytes do not loose all liver-specific functions at the same time but that subsequent stages of dedifferentiation occur. The formation of UDP-GlcUA seems to be a very basic hepatic function that can be maintained by the cells for a long time. Therefore, UDP-GlcUA content is another valuable parameter for characterizing the in vitro dedifferentiation of primary porcine hepatocyes.

The situation for UDP activated hexoses was shown to be slightly different. The hepatocytes did not maintain their high cellular level of UDP-hexoses of 24 fmol for the period of 16 days investigated (Fig. 3a), but immediately started to reduce their content under DG conditions. In contrast, the same cells cultured under SG mode showed a constant low level of UDP-Hex from the beginning of the culture. This behavior can be explained by the high turnover rate of UDP activated hexoses due to their role as precursor molecules. In contrast, UDP-GlcUA is used for being conjugated to xenobiotics (Soars et al. 2001) and will accumulate until being used (Soars et al. 2002).

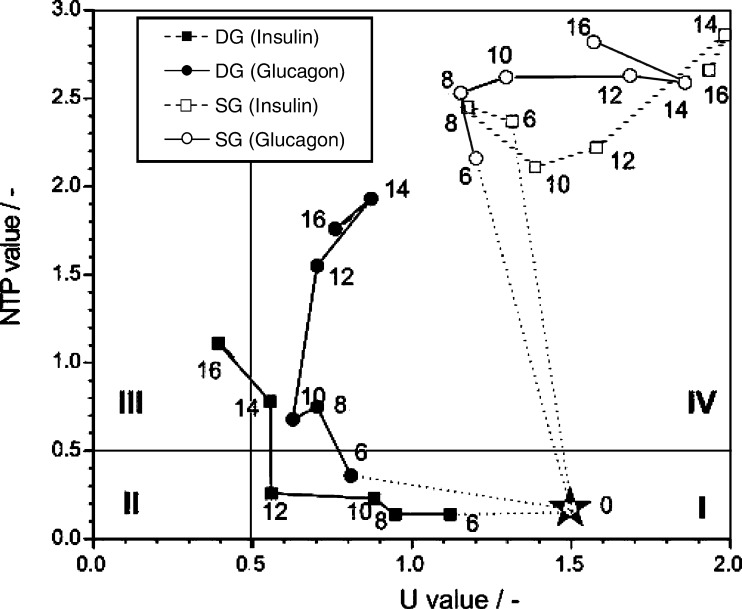

Nucleotide ratios

Ryll and Wagner (1992) proposed the so-called NTP–U plot as a useful tool for process control which has been later successfully applied in different mammalian cell culture processes (Valley et al. 1993; Deutschmann et al. 1994; Grammatikos et al. 1999). Here, we first used the NTP–U plot to characterize dedifferentiation of in vitro-cultured primary porcine hepatocytes. Figure 7 shows different regions covered by the calculated values for different phases of the cultivation. Based on the fact that the albumin secretion rate in cell culture dishes did not reach the in vivo-like rates obtained in a flat membrane bioreactor as reported by De Bartolo et al. (2000) it is suggested that the dedifferentiation is initiated earlier than monitored by the albumin secretion rate. Taken this information into account and correlated to the data obtained for a stable and high albumin secretion rate and the cellular UDP-GlcUA content (Fig. 1), we defined four regions by strictly fixing differentiation-specific threshold values already at 0.5 for the NTP and the U value, respectively, which are indicated by the two lines in Fig. 7. This threshold was chosen because the NTP/U ratio rapidly increased for cells exceeding a value of 0.5 indicating a drastic change in the cellular behavior. The NTP–U value characteristic for freshly isolated cells in Fig. 7 were determined from data obtained by several cell extractions of non-cultured freshly isolated hepatocytes. Region I shows NTP–U values determined from fully differentiated functional porcine hepatocytes whereas NTP–U values in region IV were calculated from dedifferentiated cells. Significant data for values in region II and III could not be determined from cells cultured under the applied conditions. Only DG-cultivated cells under the regulation of insulin maintained their functional differentiation for 12 days supported by the continuous secretion of high amounts of albumin (Fig. 1). Glucagon-regulated DG-cultured cells, however, entered region IV already very early after day 6 of cultivation. When comparing this result based on nucleotide ratios with the albumin secretion rate, the transition of the cells to the dedifferentiated status could not exactly be determined because a slight increase of the albumin secretion rate was observed up to day 16 of cultivation (Fig. 1). A definitely dedifferentiated character was shown for the respective hepatocytes cultured under SG mode, independent from the presence of any hormone (Fig. 7), although a constant low albumin secretion rate up to day 10 could be observed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 7.

NTP–U plot of porcine hepatocytes grown under DG and SG conditions and supplemented with different hormones (n = 2)

Conclusion

The behavior of specific intracellular nucleotide ratios has been shown to correlate to the dedifferentiation of in vitro-cultured hepatocytes monitored by selected metabolic key parameters of functional hepatocytes. All these parameters can be used to characterize different stages of differentiation of primary hepatocytes cultivated under different conditions. Nucleoside triphosphate as well as U ratios and particularly the combination of both in the NTP–U plot revealed a reliable tool for monitoring the status of differentiation and the speed of dedifferentiation of hepatocytes in culture (Fig. 7). By applying the NTP–U plot to cultured hepatocytes, the current state of the cells can be determined by the migration and the present distance to the cell-specific borderlines, which indicates the transition of cells from the differentiated functional state (see rectangular I in Fig. 7) to dedifferentiation (see rectangular IV in Fig. 7). We could show for primary porcine hepatocytes, that nucleotide ratios can be affected by a change of tissue-specific functional properties, which once more emphasizes their potential role in all cellular aspects.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Mark Smith as a native speaker for helpful assistance in proofreading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADP

adenosine-5′-diphosphate

- AEC

adenylate energy charge

- AMP

adenosine-5′-monophosphate

- ATP

adenosine-5′-triphosphate

- CTP

cytidine-5′-triphosphate

- DG

double gel

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether) N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- FALGPA

furylarcraloyl-Leu-Gly-Pro-Ala

- GlcUA

glucuronate

- GTP

guanosine-5′-triphosphate

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- GPDH

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid)

- Hex

hexose

- HK

hexokinase

- IP-RP-HPLC

ion pair reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- NTP

nucleoside triphosphate

- PFK

phosphofructokinase

- PK

pyruvate kinase

- OPA

o-phthaldialdehyde

- PCA

perchloric acid

- SG

single gel

- U

uridine

- UDP

uridine-5′-diphosphate

- UDP-Gal

UDP-galactose

- UDP-GalNAc

UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine

- UDP-Glc

UDP-glucose

- UDP-GlcNAc

UDP-N-acetylglucosamine

- UDPGNAc

sum of UDP-GalNAc and UDP-GlcNAc

- UDP-Hex

UDP-Hexose (UDP-Gal, UDP-Glc)

- UDP-GlcUA

UDP-glucuronate

- UTP

uridine-5′-triphosphate

References

- Atkinson DA. Cellular energy metabolism and its regulation. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Andus T, Geiger T, Hirano T, Kishimoto T, Tran-thi TA, Decker K, Heinrich PC. Regulation of synthesis and secretion of major acute-phase proteins by recombinant human interleukin-6 (BSF-2/IL-6) in hepatocyte primary culture. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annoni G, Weiner FR, Colombo M, Czaja MJ, Zern MA. Albumin and collagen gene regulation in alcohol- and virus-induced human liver. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader A, Bartolo L, Haverich A. High level benzodiazepine and ammonia clearance by flat membrane bioreactors with porcine liver cells. J Biotechnol. 2000;81:95–105. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader A, Bartolo L, Haverich A. Initial evaluation of the performance of a scaled-up flat membrane bioreactor (FMB) with pig liver cells. In: Crepaldi G, Demetrioou AA, Muraca M, editors. Bioartificial liver: the critical issues. Rome: CIC International Editions; 1997. pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bader A, Knop E, Frühauf N, Crome O, Boker K, Christians U, Oldhafer K, Ringe B, Pichlmayr R, Sewing KF. Reconstruction of liver tissue in vitro: geometry and characteristic flat bed, holllow fiber, and spouted bed bioreactors with reference to the in vivo liver. Artif Organs. 1995;19:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1995.tb02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau N, Sympson CJ, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Suppression of ICE and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells by extracellular matrix. Science. 1995;267:891–893. doi: 10.1126/science.7531366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher NL, Robinson GS, Farmer SR. Effects of extracellular matrix on hepatocyte growth and gene expression: implications for hepatic regeneration and the repair of liver injury. Sem Liver Dis. 1990;10:11–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabaza A, Guinovart JJ, Ciudad CJ. Activation of hepatocyte glycogen synthase by metabolic inhibitors. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;250:469–475. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castell JV, Gomez-Lechon MJ, David M, Fabra R, Trullenque R, Heinrich PC. Acute-phase response of human hepatocytes: Regulation of acute-phase protein synthesis by interleukin-6. Hepatology. 1991;12:1179–1186. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney AL, Marbach EP. Modified reagents for the determination of urea and ammonia. Clin Chem. 1962;8:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou IN, Zeiger J, Rapaport E. Imbalance of total cellular nucleotide pools and mechanism of the colchicine-induced cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2401–2405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolo L, Jarosch Schweder G, Haverich A, Bader A. A novel full-scale flat membrane bioreactor utilizing porcine hepatocytes: Cell viability and tissue-specific functions. Biotechnol Prog. 2000;16:102–108. doi: 10.1021/bp990128o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou AA, Whiting J, Levenson SM, Chowdhury NR, Schechner R, Michalski S, Feldman D, Chowdhury JR. New method of hepatocyte transplantation and extracorporeal liver support. Ann Surg. 1986;204:259–270. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198609000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschmann SM, Valley U, Jäger V, Wagner R. Cell cycle analysis as a tool for control and regulation of mammalian cell cultures in bioreactors. In: Spier RE, Griffiths JB, Berthold W, editors. Animal cell technology: products of today, prospects of tomorrow. Oxford, UK: Butterworths-Heinemann; 1994. pp. 354–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JCY, Tompkins RG, Yarmoush ML. Long-term in vitro function of adult hepatocytes in a collagen sandwich configuration. Biotechnol Prog. 1991;7:237–245. doi: 10.1021/bp00009a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JCY, Yarmush ML, Koebe HG, Tompkins RG. Hepatocyte function and extracellular matrix geometry: long-term culture in a sandwich configuration. FASEB J. 1989;3:174–177. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.2.2914628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg K, Chandramouli V, Kumaran K, Schumann WC, Wahren J, Landau BR. Gluconeogenesis and glucuronidation in liver in vivo and the heterogeneity of hepatocyte function. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21715–21717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsdale T, Bard J. Collagen substrata for studies on cell behaviour. J Cell Biol. 1972;54:626–637. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.3.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Orend G, Watanabe N, Hunter T, Ruoslahti E. Dependence of cyclin E-CDK2 kinase activity on cell anchorage. Science. 1996;271:499–502. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flendrig LM, Soe JW, Joerning GGA, Steenbeck A, Karlsen OT, Bovee WM, Ladiges NC, te-Velde AA, Chamuleau RA. In vitro evaluation of a novel bioreactor based on an integral oxygenator and a spirally wound nonwoven polyester matrix for hepatocyte culture as small aggregates. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1379–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80475-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlitzek M, Valley U, Wagner R. Ammonium ion/glucosamine dependent increase of oligosaccharide complexity in recombinant glycoproteins secreted from cultivated BHK-21 cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;57:518–528. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980305)57:5<518::AID-BIT3>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlitzek M, Papac DI, Sliwkowski MB, Ryll T. Incorporation of 15N from ammonium into the N-linked oligosaccharides of an immunoadhesin glycoprotein expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Glycobiology. 1999;9:125–131. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauldie J, Richards C, Harnish D, Landsorp P, Baumann H. Interferon β2/B-cell stimulatory factor type 2 shares identity with monocyte-derived hepatocyte-stimulating factor and regulates the majur acute-phase protein response in liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7251–7255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach J, Schnoy N, Smith MD, Neuhaus P. Hepatocyte culture between woven capillary network-A micros-copy study. Artif Organs. 1994;18:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1994.tb02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikos SI, Tobien K, Noë W, Werner RG. Monitoring of intracellular ribonucleotide pools is a powerful tool in the development and characterization of mammalian cell culture processes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;64:357–367. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990805)64:3<357::AID-BIT12>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummt F, Paul D, Grummt I. Regulation of ATP pools, rRNA and DNA synthesis in 3T3 cells in response to serum or hypoxanthine. Eur J Biochem. 1977;76:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba T, Tait A, Nakano M, Mahon WA, Kalow W. Metabolism of diazepam in vitro by human liver. Drug Metab Depos. 1988;16:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Okanoue T, Enjo F, Sakamoto S, Takami S, Yasui K, Kagawa K, Kashima K. Regulation of hepatocyte albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein secretion by monokines, dexamethasone, and nitric oxide synthase pathway: Significance of activated liver nonparenchymal cells. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:851–859. doi: 10.1007/BF02087433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Sung SR, Choi EH, Kim YI, Kim KJ, Dong SH, Kim HJ, Chang YW, Lee JI, Chang R. Dedifferentation of conditionally immortalized hepatocytes with long-term in vitro passage. Exp Mol Med. 2000;32:29–37. doi: 10.1038/emm.2000.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Goto M, Kobayashi K, Akaike T. Receptor-mediated regulation of differentiation and proliferation of hepatocytes by synthetic polymer model of asialoglycoprotein. J Biomater Sci Polymer Edn. 1994;6:325–342. doi: 10.1163/156856295x00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koj A, Gauldie J, Regoeczi E, Sauder DN, Sweeney GD. The acute-phase response of cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1984;224:505–514. doi: 10.1042/bj2240505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BR, West FG. A method for quantitative amino acid analysis using precolumn o-phthaldialdehyd derivatization and high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci. 1981;19:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith JE, Jr, Fazeli B, Schwartz MA. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:953–961. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.9.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miners JO, Mackenzie PI. Drug glucuronidation in humans. Pharmacol Ther. 1991;5:347–369. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90065-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphree S, Moore EC, Peterson D. Temporal variation of adenine ribonucleotides during the cell cycle of Chinese hamster fibroblasts in culture. Exp Cell Res. 1974;83:189–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oude Elferink RP, Jansen PL. The role of the canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in the disposal of endo- and xenobiotics. Pharmacol Ther. 1994;64:77–97. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranucci CS, Kumar A, Surenda PB, Moghe PV. Control of hepatocyte function on collagen foams: sizing matrix pores toward selective induction of 2-D and 3-D cellular morphogenesis. Biomaterials. 2000;21:783–793. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport E, Garcia-Blanco MA, Zamecnik PC. Regulation of DNA replication in S phase nuclei by ATP and ADP pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1643–1647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re F, Zanetti A, Sironi M, Polentarutti N, Lanfrancone L, Dejana E, Colotta F. Inhibition of anchorage-dependent cell spreading triggers apoptosis in cultured human endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:537–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild MA, Oratz M, Schreiber SS. Serum albumin. Hepatology. 1988;8:385–401. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryll T, Valley U, Wagner R. Biochemistry of growth inhibition by ammonium ions in mammalian cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44:184–119. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryll T, Wagner R. An improved ion-pair HPLC method for the quantification of a wide variety of nucleotides and sugar-nucleotides in animal cells. J Chromatogr. 1991;570:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(91)80202-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryll T, Wagner R. Intracellular ribonucleotide pools as a tool for monitoring the physiological state of in vitro cultivated mammalian cells during production processes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;40:934–946. doi: 10.1002/bit.260400810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soars MG, Buchell B, Riley RJ. In vitro analysis of human drug glucuronidation and prediction of in vivo metabolic clearance. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2002;301:382–390. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soars MG, Riley RJ, Findlay KAB, Coffey MJ, Burchell B. Evidence for significant differences in microsomal drug glucuronidation by canine and human liver and kidney. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilles AW, Baskaran H, Roy P, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Effects of oxygenaton and flow on the viability and function of rat hepatocytes cocultured in a microchannel flat-plate bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;73:379–389. doi: 10.1002/bit.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobe S, Takei Y, Kobayashi K, Akaide T. Receptor-mediated formation of multilayer aggregates of primary cultured adult rat hepatocytes on lactose-substituted polysterene. Biophys Biochem Res Commun. 1992;184:225–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)91182-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valley U, Ryll T, Wagner R. Process control of BHK cells by nucleotide pool measurement. In: Kaminogawa S, Ametani A, Hachimura S, editors. Animal cell technology: basic and applied aspects. Dordrecht: Kluwer Acad Pub; 1993. pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Valley U, Nimtz M, Conradt HS, Wagner R. Incorporation of ammonium into intracellular UDP-activated N-acetylhexosamines and into carbohydrate structures in glycoproteins. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;64:401–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990820)64:4<401::AID-BIT3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K, Sumiyoshi N, Nakashima Y, Michibayashi N, Kawase N, Miura Y, Mizoguchi T. Stimulation of liver functions in hierachical co-culture of bone marrow cells and hepatocytes. Cytotechnology. 1998;26:5–12. doi: 10.1023/A:1007938118602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Ohtsubo M, Boehmer RM, Assoian RK. Adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression linked to the expression of cyclin D1, activation of cyclin E-cdk2 and phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:392–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]