Abstract

Up to 20% of all primary CNS lymphoma (PCNLS) patients are aged 80 years or older, yet data are limited on how best to treat this rapidly growing population. Despite demographic pressures and the proven efficacy of methotrexate (MTX)-based regimens, automatic de-escalation of care based on age is standard practice outside of tertiary care centers. We performed a retrospective review of all PCNSL patients aged 80 years or older treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1993 to 2011. Demographic and clinical variables were evaluated as predictors of survival by multivariate analysis. Twenty-three of 24 patients were treated with chemotherapy (92% with high-dose MTX, typically in combination with vincristine and procarbazine). One patient received ocular radiation alone for disease limited to the eyes. Response to treatment was noted in 62.5% of patients; 9 (37.5%) had refractory disease. Median overall survival was 7.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.8–53), and median progression-free survival was 6.5 months (95% CI: 4.4–29.5). Two-year survival rate was 33%; 3-year survival rate was 17%. Three patients lived more than 4 years postdiagnosis. Most patients tolerated therapy well, and despite low baseline creatinine clearance, no significant renal toxicity was noted. Response status and deep brain involvement were identified as the most important predictors of survival. Multidrug regimens containing high-dose MTX are feasible and efficacious among the oldest patients, particularly those who achieve a complete response by their fifth treatment cycle. Aggressive therapy should be offered to select patients irrespective of advanced age.

Keywords: chemotherapy, elderly, primary central nervous system lymphoma, quality of life

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare variant of non-Hodgkin lymphoma confined to the brain, leptomeninges, spinal cord, or eyes. Although it accounts for less than5% of all primary brain tumors, the age-adjusted incidence of PCNSL has increased substantially over the past 30 years.1 Nearly half of all cases of PCNSL occur among patients older than 60 years, and 20% of those affected are 80 years or older, yet data are limited on how best to manage the disease in the elderly.2 This is due in part to their limited participation in clinical trials, as well as the hesitancy on the part of many clinicians to treat older patients with aggressive therapy.3 While a few recent studies have attempted to address this gap, data on the oldest patients—80 years or older—are lacking.4,5 Given that this group comprises the fastest-growing segment of the United States population, with a growth rate 3 times that of the total, exploring therapeutic strategies among the very old should be a priority.6

Older age is a well-established negative prognostic marker, and, compared with their younger counterparts, patients 60 years or older die earlier of their disease, despite identical therapy with methotrexate (MTX)-based regimens.7–9 Moreover, those who do survive are more susceptible to neurocognitive sequelae.10 In an effort to minimize the latter, recent trials have explored the use of MTX-based therapy without whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), and while these regimens have been promising, with less cognitive dysfunction and comparable overall survival (OS) times of 14–37 months, responses are less durable.9,11–14

Despite these advances, chemotherapy remains underutilized outside tertiary care centers, particularly among the elderly. According to a population-based Medicare study of 579 patients diagnosed with PCNSL from 1994 to 2002, age was inversely correlated with the chance of treatment with MTX, and up to 82% of patients 80 years or older received either radiotherapy alone or no treatment at all.3 While it is increasingly clear that such automatic de-escalation of care based on age is not appropriate, caution is warranted. The elderly are more likely to have compromised renal function, limited bone marrow reserve, and decreased cardiac output—physiologic changes that may result in greater toxicity and reduced efficacy from MTX.15 Identifying clinical predictors that allow clinicians to determine who will benefit from vigorous treatment vs those who will not is important. In this study, we attempt to characterize and evaluate prognostic factors among a cohort of the oldest PCNSL patients treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The MSKCC institutional database was used to identify patients with PCNSL who were diagnosed at 80 years or older between 1993 and 2011. Data were collected by chart review, and response was determined by contrast-enhanced MRI or CT. To qualify as a complete response (CR), patients had to have complete disappearance of all contrast-enhancing lesions.

To evaluate predictors of OS, we analyzed demographic, clinical, and treatment variables for their impacts on survival time. We examined completion of 5 or more cycles of MTX-based chemotherapy as a measure of a patient receiving reasonably adequate therapy and because this is a time point where we typically perform routine imaging for efficacy. This retrospective study was approved by the MSKCC Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analyses

The following baseline demographic variables were studied: patient age, sex, marital status, and year of diagnosis. Clinical variables included Karnofsky performance status (KPS), duration of symptoms prior to treatment, deep brain involvement, presentation with altered mental status, hemiparesis, baseline hemoglobin, and creatinine clearance as calculated by the Cockgroft–Gault method. Treatment-related variables included number of MTX cycles and response status. All variables except age were dichotomized in the analysis. A KPS of 70 was used as the cut point, as this defines the capacity for independent self-care. To evaluate time trends over the course of 19 years, patients were dichotomized by diagnosis before and after 2002. Pretreatment anemia was defined as a hemoglobin value less than 10 g/dL, and a creatinine clearance rate of 50 mL/min was selected as a cut point to stratify baseline renal function.15,16 Patients were also dichotomized based on whether they completed a minimum of 5 cycles of intravenous MTX.

OS was measured from the date of diagnosis as defined by the date on which pathological disease confirmation was obtained until death or last follow-up. Kaplan–Meier survival distributions were estimated to assess OS and progression-free survival (PFS). Data were collected through December 31, 2011, which was used as the censoring date for survivors. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were fit to analyze predictors of survival, and a log-rank test was applied to compare survival curves. A multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was used to analyze predictors of survival that were univariately significant at the α < 0.10 level. Simple logistic regression models were analyzed to identify potential predictors affecting discharge destination. The small sample size precluded multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software (Intercooled version 12.0).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-four patients aged 80 years or older were treated for PCNSL between 1993 and 2011 (Table 1). The median age at diagnosis was 82 (range, 80–90 years), and median KPS was 50 (range, 30–90). There was a predominance of women (67%), and 58% of patients were married. Most patients (71%) were diagnosed after 2002.

Table 1.

Oldest PCNSL Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| • 80-85 | 19 | 79% |

| • 85-90 | 5 | 21% |

| Sex | ||

| • Women | 16 | 67% |

| • Men | 8 | 33% |

| Marital status | ||

| • Married | 14 | 58% |

| • Unmarried | 10 | 42% |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| • Before 2002 | 7 | 29% |

| • After 2002 | 17 | 71% |

| KPS at presentation | ||

| • <70 | 18 | 75% |

| • ≥70 | 6 | 25% |

| Pre-treatment symptom duration | ||

| • ≥1 months | 16 | 67% |

| • <1 months | 8 | 33% |

| Deep brain involvement | ||

| • Yes | 12 | 50% |

| • No | 12 | 50% |

| Ocular involvement | ||

| • Yes | 3 | 13% |

| • No | 21 | 87% |

| Positive CSF cytology | ||

| • Yes | 3 | 13% |

| • No | 19 | 79% |

| • Suspicious | 2 | 8.3% |

| Hemiparesis | ||

| • Yes | 6 | 25% |

| • No | 18 | 75% |

| Changes in cognition or personality | ||

| • Yes | 15 | 63% |

| • No | 9 | 37% |

| Aphasia | ||

| • Yes | 4 | 17% |

| • No | 20 | 83% |

| Seizures | ||

| • Yes | 2 | 8% |

| • No | 22 | 92% |

| Creatinine Clearance | ||

| • <50 mL/min | 7 | 29% |

| •≥50 mL/min | 13 | 54% |

| • Missing | 4 | 17% |

Abbreviations: KPS, Karnofsky performance status; MTX, methotrexate; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Fifteen patients (62.5%) presented with cognitive or personality changes, and, in at least 3, diagnosis was delayed because such symptoms were attributed to mild cognitive impairment of aging or frank dementia. Six patients (25%) presented with hemiparesis, 4 (16.6%) with aphasia, and 2 (8.3%) with seizures. Twenty-three had parenchymal brain lesions, and 1 had isolated ocular lymphoma.

At diagnosis all patients underwent staging with ophthalmological evaluation, bone marrow biopsy, body imaging, and lumbar puncture. Three (12.5%) had clear evidence of leptomeningeal disease on analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); an additional 2 (8.3%) had atypical lymphocytes considered suspicious for lymphoma. Three patients (12.5%) had ocular involvement (1 isolated), and all were confirmed by vitreal biopsy. No patients had systemic or bone marrow involvement.

Eight patients (33%) initiated treatment within 1 month of symptom onset; the remainder (67%) had more prolonged symptom duration before seeking medical attention. Once the appropriate diagnosis had been made, however, median time between diagnosis of intracranial disease and initiation of chemotherapy was 15 days (range, 4–41).

Laboratory data required to determine baseline creatinine clearance were available on 20 patients. Of these, 13 (65%) had a clearance rate of ≥50 mL/min as calculated by Cockcroft–Gault; 7 (35%) had values below this, ranging from 28 to 45 mL/min. All patients had normal white cell counts and platelets; 3 (12.5%) initiated treatment with hemoglobin below 10 g/dL.

Initial Treatment

All but 2 patients (92%) received some form of high-dose MTX-based therapy, usually in combination with vincristine and procarbazine (MVP) (Table 2 and Appendix). The patient who had isolated ocular lymphoma opted for ocular radiation alone; another wished to avoid inpatient treatment and chose a course of procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) before pursuing supportive care.

Table 2.

Response summary for the oldest PCNSL patients treated with MTX

| n | CR (% of N) | PR (% of N) | Refractory (% of N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All treatment | 24 | 14 (58.3) | 1 (4.2) | 9 (37.5) |

| MTX baseda | 22 | 13 (59) | 1 (4.5) | 8 (36.5) |

| ≥5 cycles | 14 | 12b (86) | – | 2 (14) |

| <5 cycles | 8 | 1b (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (75) |

| PCV | 1 | – | – | 1 (100) |

| Ocular RT | 1 | 1 (100) | – | – |

a 6 patients treated with high-dose MTX also received Ara-C as consolidation; 5 after ≥5 cycles, 1 after only 4 cycles of MTX.

b 1 patient had near-CR with 6 cycles MTX alone but achieved CR after consolidation with Ara-C.

c 1 patient had near-CR with 4 cycles MTX alone but achieved CR after consolidation with Ara-C.

Abbreviations: CR, complete recovery; PR, partial recovery; MTX, methotrexate; PCV, procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine; RT, radiotherapy.

Among the 22 patients treated with MTX, 17 (77.3%) initiated treatment at a dosage of 3.5 g/m2. The remaining 5 started at dosages ranging from 1 to 2.5 g/m2. One patient was treated with 1 g/m2 in deference to his advanced age (89 years). The oldest patient in the cohort (90 years) started at a dosage of 2 g/m2 owing to concerns about multiple comorbidities; this was eventually raised to 3 g/m2 but lowered again to 2.5 g/m2 when he developed a grade 2 pleural effusion. An 86-year-old also started at 2 g/m2, but this dosage was later titrated to 3.5 g/m2. Two additional patients initiated treatment at 2–2.5 g/m2 owing to low baseline creatinine clearance in the range 28–42 mL/min; they completed MTX at the reduced dosage.

Only 2 of the patients who started at 3.5 g/m2 required dosage reductions. One had his dosage lowered to 1 g/m2 after a delay in clearance, and no attempts were made to re-escalate. The second patient was given 2.5 g/m2 for cycles 3 and 5 in response to transient grade 2 elevations in creatinine; all other cycles were at the full dosage.

All patients were admitted to the hospital for each cycle of MTX, which was administered every 2 weeks as a 2-hour infusion followed 24 hours later by calcium leucovorin rescue. Vincristine was given at dosages ranging from 1 to 1.4 mg/m2 on the first day of each cycle, and procarbazine was given on days 1–7 of every other cycle at a dosage of 100 mg/m2/day. Patients were discharged from the hospital once their MTX serum level was ≤100 nmol/L. Two patients were treated with 500 mg/m2 of rituximab (R) in combination with MTX. Fourteen patients (64% of those treated with MTX) completed at least 5 cycles of MTX, and 5 underwent consolidation therapy with high-dose cytarabine (Ara-C). One patient received Ara-C after only 4 cycles of MTX. Eight patients were either unwilling to continue high-dose MTX or unable to tolerate a full course of treatment due to clinical deterioration or toxicity. No patient with a positive CSF cytology received intrathecal chemotherapy.

Vincristine was used in combination with high-dose MTX in all but 2 patients. One received initial treatment at an outside institution whose clinical practice did not include use of this agent. The other patient presented with an ileus, which led treating physicians to withold vincristine out of fear of exacerbating a preexisting autonomic neuropathy. Two patients had their dosages capped at 2 mg daily at the outset of treatment in deference to their age; all other patients received a standard dosage of 1.4 mg/m2. Only 1 patient underwent a dosage reduction (from 1.4 to 1.2 mg/m2) for a mild peripheral neuropathy.

Cranial radiotherapy was used as part of initial treatment in only 1 patient, who received 900 cGy at an outside institution upon discovery of an intracranial mass but prior to pathological diagnosis. Once the diagnosis was established, radiation was stopped and the patient was referred to MSKCC for chemotherapy. No other patient received any treatment prior to MTX.

Salvage Treatment

Salvage treatment was used in 5 patients. One patient who had clinical and radiographic progression after only 2 cycles of MTX was given a single dose of Ara-C, but she continued to deteriorate clinically and was eventually transferred to a nursing home. Two patients were treated with a combination of R and temozolomide (TMZ): 1 for primary refractory disease after 5 cycles of MTX and another at recurrence; 1 patient received TMZ alone at recurrence. All 4 of these patients failed to respond to salvage treatment. One patient who developed ocular and intracranial disease at recurrence achieved a second CR with ocular radiation followed by 7 cycles of R, MTX, and procarbazine. No patient received WBRT for salvage therapy.

Outcomes

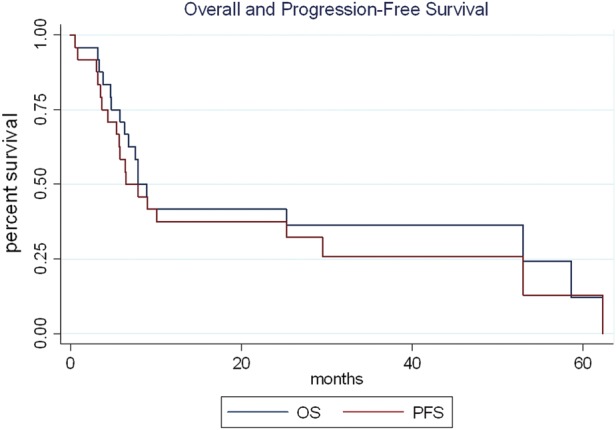

Fifteen patients in this series (62.5%) had a response to initial treatment: 14 CR and 1 partial response (PR) (Table 2). Of the 22 patients treated with MTX-based chemotherapy, 11 (50%) experienced CR with MVP alone. Two patients had near CR following MVP but required consolidation with Ara-C before they achieved CR. One patient with isolated ocular disease achieved CR with radiation alone. The single patient with PR was lost to follow-up before additional imaging could be obtained. Eight patients treated with MVP (36%) had refractory disease. The patient treated with PCV had a rapid clinical decline after only 1 cycle and opted to forgo further therapy. Median PFS for the entire cohort was 6.5 months (95% CI: 4.4–29.5).

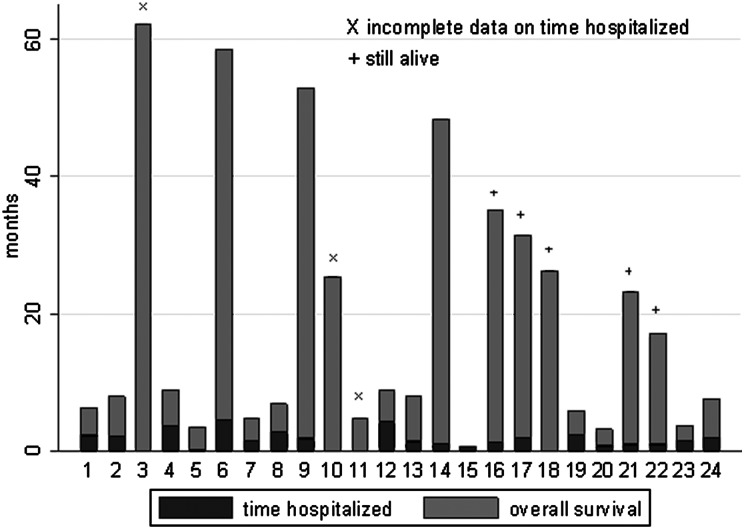

Six patients (25%) were alive at the study's end, 4 without recurrence. Fifteen patients died: 12 from PCNSL, 1 from pulmonary toxicity during MVP treatment, 1 from heart failure after a prolonged period in remission, and 1 from respiratory failure owing to either pneumonia or pulmonary embolism during salvage with R-TMZ. Three patients were lost to follow-up. The median OS for the entire cohort was 7.9 months (95% CI: 5.8–53) (Fig. 1). One-year survival rate from diagnosis was 42%, 2-year survival was 33%, and 3-year survival was 17%. Three patients (12.5%) lived more than 4 years postdiagnosis. Median follow-up for survivors was 15 months.

Fig. 1.

Overall and progression-free survival in oldest PCNSL patients.

Among patients with CR (n = 14), KPS improved by 20 points, from a median baseline of 60 (40–80) to a median of 80 (60–100). Those who did not achieve CR (n = 10) made no gains in performance status; their median KPS remained 50 (range 30–70).

Age, the absence of deep brain involvement, completion of 5 cycles of MTX, and initial CR by MRI or CT were found to be the only significant predictors of OS in the univariate analysis (Table 3). In the multivariate model, only CR status and deep brain involvement achieved statistical significance, with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.2 and 3.3, respectively.

Table 3.

Predictors of survival for the oldest PCNSL patients

| Variable | No. (%) of Patients | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (continuous variable) | – | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.04 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.3 |

| Male gender | 8 (33) | 0.7 (0.3–2.0) | 0.6 | ||

| Diagnosis after 2002 | 17 (71) | 1.0 (0.3–2.8) | 0.92 | ||

| Pretreatment KPS ≥70 | 6 (25) | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) | 0.6 | ||

| Symptom duration ≥1 month | 16 (67) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 0.2 | ||

| Deep brain involvement | 12 (50) | 4.1 (1.4–12) | 0.01 | 3.3 (1.0–10.8) | 0.05 |

| Hemiparesis | 6 (25) | 0.6 (0.2–2.0) | 0.4 | ||

| Altered mental status | 15 (62.5) | 2.4 (0.8–7.4) | 0.13 | ||

| Hemoglobin < 10 | 3 (12.5) | 1.3 (0.4–4.5) | 0.7 | ||

| Creatinine <50 mL/min | 7 (30) | 1.9 (0.7–5.2) | 0.2 | ||

| Completed ≥5 cycles of MTX | 14 (58.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.02 | 0.6 (0.17–2.1) | 0.4 |

| Achieved CR | 14 (61) | 0.1 (0.04–0.4) | 0.00 | 0.3 (0.07–0.9) | 0.04 |

Significant P values are bolded. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; MTX, methotrexate; CR, complete recovery.

Toxicity

The majority of patients (n = 14; 58%) tolerated therapy well. During MTX-based treatment, 10 patients experienced a grade III or IV toxicity, primarily bone marrow suppression or infection (Table 4). One patient experienced fatal respiratory failure (grade V dyspnea/hypoxia) from either a pulmonary embolism or pneumonia. Two had exacerbations of baseline congestive heart failure likely related to hydration required for MTX. One patient had a cardiac arrest likely unrelated to treatment; he made a full recovery and died cancer free more than 4 years later of heart failure. While several patients had transient, grade II elevations in creatinine, only 2 dosage reductions of MTX took place for this reason.

Table 4.

MVP-related grade III–V toxicities in the oldest PCNSL patients, n = 22 patients (%)

| Grade III | Grade IV | Grade V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukopenia | 5 (23) | 2 (9) | |

| Anemia | 3 (14) | ||

| Infection | 3 (14) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Thrombosis | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Cardiac | 2 (9) | ||

| Fatigue | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Respiratory failure | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) |

Time spent hospitalized from date of diagnosis until death or last follow-up was available for 22 patients (Fig. 2 and Appendix). Three received additional care at institutions other than MSKCC, making an accurate assessment of complete inpatient time unobtainable. Among those who were treated solely at MSKCC, the median time spent hospitalized was 42.5 days (range, 2–133). Upon completion of initial course of treatment, 17/24 patients (71%) returned home, 1 died of respiratory failure in the intensive care unit after only 1 cycle of MVP, and the remaining 6 were discharged to hospice or a nursing home.

Fig. 2.

Time spent hospitalized as percent of survival of the oldest PCNSL patients.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that treatment with MTX-based regimens is effective and safe among the oldest PCNSL patients and may result in prolonged survival, particularly for those patients who responded after 5 cycles of induction therapy. By study's end, at least 20% of patients had lived more than 30 months from diagnosis, a benchmark typically seen with much younger cohorts.4,5,17,18 Moreover, as of December 31, 2011, 6 patients (25%) were still alive, with a median follow-up of 15 months. Median OS for the entire cohort was 7.9 months, a value that compares favorably with a median of 7.6 months achieved with WBRT alone for younger patients aged ≥60 years.19,20 However, it is substantially less than the 37- to 51-month median survival seen in larger cohorts of all patients treated with a comparable regimen.11,18,20 Although age dropped out as a significant prognostic factor in our multivariate analysis, this was likely a consequence of the small number of patients. It is noteworthy that only 1 of the 5 patients aged 85 years or older survived more than 1 year, and all 8 patients who survived almost 2 years or longer were aged 80–84 at diagnosis.

Despite their advanced age, most of our patients tolerated therapy well. No one developed higher than a grade II nephrotoxicity, and there were only 2 MTX dosage reductions for a transient rise in creatinine. Only 1 patient developed a dose-limiting peripheral neuropathy related to vincristine. In contrast, myelotoxicity was more common in this elderly population, a finding consistent with previous work in geriatric oncology that demonstrated an inverse association between aging and bone marrow reserve.15,21,22 All patients who initiated treatment at our institution received a combination regimen that included vincristine and procarbazine. The only patient to receive single-agent MTX was treated elsewhere, highlighting important differences in clinical practice and a lack of consensus on the best approach to therapy. While some investigators have questioned the use of multidrug combinations, postulating that they offer limited survival benefit at the cost of added toxicity, studies using single-agent MTX show poor PFS, and a recent randomized phase II trial strongly indicates the benefit of combination therapy.23–26

A majority of patients (71%) were treated after 2002, yet no one diagnosed prior to this time received WBRT. As the delayed neurocognitive effects of radiation were not fully recognized until the late 1990s, this finding is somewhat unusual and likely reflects MSKCC's more vigorous use of MTX.27–29 The overall increase in number of octogenarians treated since 2002 also reflects increasing physician comfort with evaluating intracranial masses in the elderly and a growing commitment to their vigorous diagnosis and treatment. Alternative explanations for the upsurge include a change in referral patterns, demographic shifts, and greater awareness of the potential benefits of chemotherapy for PCNSL.

There is a growing appreciation for the importance of quality of life in addition to survival, particularly among the elderly.30 An additional 8 months of life may make chemotherapy worthwhile to many octogenarians, but perhaps less so if much of that time is spent hospitalized. This study is the first to focus exclusively on the oldest PCNSL patients. It is also unique in its reporting of quality-of-life surrogates such as days spent hospitalized and discharge destination. The majority (71%) of patients were able to return home after initial treatment, particularly those who were able to complete all 5 cycles of MTX. While this finding may reflect improved social support among patients who seek and obtain aggressive therapy, it could also be considered predictive of improved clinical outcome. Taken together with our multivariate analysis that identified initial response as a predictor of OS, we might conclude that achieving an objective response after 5 cycles of induction chemotherapy is predictive not only of longer life but also of clinical benefit and improved function.

The current study has several limitations. First, there may be significant referral bias among patients treated at MSKCC, as it is less likely that the most debilitated elderly would be sent to a tertiary care center. Second, the retrospective nature of this study means that relevant patient characteristics such as nutritional status, comorbidities, polypharmacy, precise steroid dosing, detailed neurocognitive evaluations, and geriatric assessments were unavailable. Third, the relatively small sample size limited our power to detect potentially important associations between patient characteristics and clinical outcomes of interest. Despite these and other limitations, this is the largest study of patients aged 80 years or older treated for PCNSL. It suggests that many of these patients can tolerate a high-dose MTX-based regimen, and every elderly patient with PCNSL should be evaluated for full-dose chemotherapy. Those who achieve a response by cycle 5 can have substantial benefits in terms of survival and performance status. In contrast, octogenarians who do not respond to induction therapy are unlikely to improve and may be unnecessarily subjected to lengthy hospitalizations and added toxicities with continued treatment.

Acknowledgments

These data were previously presented as a poster at the 2011 Society of Neuro-Oncology annual meeting.

Conflict of interest statement. None reported.

Appendix

Summary of treatment, response, toxicity, and discharge destination among 24 patients with PCNSL diagnosed at age ≥80 y.

| Pt. | Age | Initial Treatment | Best Response | Grade III/IV Toxicities | Hospitalization Days/% OS | Discharge | OS (mos) | Cause of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | 4 cycles MVP, IO M spinal RT | Refractory disease | 67/35 | Home | 6.3 | PCNSL | |

| 2 | 82 | 5 cycles MVP | CR | 65/27 | Home | 7.9 | PCNSL | |

| 3 | 80 | 6 cycles MVP, IO M 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after Ara-C | Incomplete data | Home | 62.3 | LTF | |

| 4 | 81 | 900 cGy of focal RT at OSH, 4 cycles MVP, IO M 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after Ara-C | 110/40 | Nursing home | 8.9 | PCNSL | |

| 5 | 84 | 1 cycle PCV | Refractory disease | 2/2 | Nursing home | 3.4 | PCNSL | |

| 6 | 82 | 5 cycles MVP | CR | Grade III leukopenia | 133/8 | Home | 58.6 | PCNSL |

| Grade III anemia | ||||||||

| 7 | 80 | 2 cycles MVP | Refractory disease | 43/30 | Home | 4.8 | PCNSL | |

| 8 | 80 | 7 cycles MVP | CR | 84/40 | Home | 6.8 | PE v. PNA | |

| 9 | 84 | 7 cycles MVP | CR | 52/3 | Home | 53.0 | Heart failure | |

| 10 | 81 | 3 cycles MVP | PR then LTF | Grade III anemia | Incomplete data | Home | 25.3 | LTF |

| Grade IV neutropenia | ||||||||

| 11 | 81 | 5 cycles M, IO M | Refractory disease | Incomplete data | Home | 4.7 | PCNSL | |

| 12 | 83 | 5 cycles MVP | Refractory disease; MRI showed partial response, but clinically deteriorated before | Grade III anemia | 131/50 | Hospice | 9.0 | PCNSL |

| Grade III neutropenia | ||||||||

| Grade III lymphopenia | ||||||||

| Grade III opportunistic infection | ||||||||

| Grade III hypoxia | ||||||||

| 13 | 82 | 5 cycles MVP | Refractory disease | Grade III congestive heart failure | 39/17 | Home | 7.9 | PCNSL |

| 14 | 80 | 5 cycles R-MVP 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after MTX | 32/2 | Home | 48.3 | Alive | |

| 15 | 82 | 1 cycle MVP | Refractory disease | Grade IV febrile neutropenia | 18/100 | Died in ICU | 0.6 | Toxicity |

| Grade IV thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| Grade IV dyspnea | ||||||||

| 16 | 80 | 7 cycles MVP, 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after MTX | 36/3 | Home | 35.0 | Alive | |

| 17 | 80 | 5 cycles MVP, 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after MTX | 57/6 | Home | 31.4 | Alive | |

| 18 | 82 | Ocular RT only | CR | 0/0 | Home | 26.3 | Alive | |

| 19 | 90 | 5 cycles MP | CR | Grade III neutropenia | 71/41 | Nursing home | 5.8 | LTF |

| Grade III congestive heart failure | ||||||||

| 20 | 87 | 2 cycles R-MVP | Refractory disease | 21/22 | Hospice | 3.2 | PCNSL | |

| 21 | 80 | 7 cycles MVP | CR | 27/4 | Home | 23.2 | Alive | |

| 22 | 86 | 5 cycles MVP, 2 cycles Ara-C | CR after MTX | Grade III leukopenia | 27/5 | Home | 17.2 | Alive |

| 23 | 81 | 3 cycles MVP, IO M | Refractory disease | Grade III device related infection | 42/37 | Hospice | 3.8 | PCNSL |

| 24 | 85 | 5 cycles R-MVP | CR | Grade III hypokalemia | 59/26 | Home | 7.6 | PCNSL |

| Grade III thrombosis | ||||||||

| Grade III fatigue | ||||||||

| Grade III device related infection |

Abbreviations: M, methotrexate; V, vincristine; P, procarbazine; IO, intra-ommaya; Ara-C, cytarabine; TMZ, temozolomide, R, rituximab; RT, radiation therapy; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PE, pulmonary embolus; PNA, pneumonia; LTF, lost to follow-up.

aPatient's initial MRI demonstrated PR; a follow-up scan noted CR, but this could not be confirmed because patient was LTF.

References

- 1.Olson JE, Janney CA, Rao RD, et al. The continuing increase in the incidence of primary central nervous system non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1504–1510. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CBTRUS. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2004-2006. Hinsdale, IL: Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. www.cbtrus.org; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panageas KS, Elkin EB, Ben-Porat L, Deangelis LM, Abrey LE. Patterns of treatment in older adults with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Cancer. 2007;110(6):1338–1344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ney DE, Reiner AS, Panageas KS, Brown HS, DeAngelis LM, Abrey LE. Characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4605–4612. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu JJ, Gerstner ER, Engler DA, et al. High-dose methotrexate for elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(2):211–215. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Census Bureau. Age and Sex Composition: 2010. Census Briefs. Hinsdale, IL: 2011. May www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(2):266–272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrey LE, Ben-Porat L, Panageas KS, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(36):5711–5715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiel E, Korfel A, Martus P, et al. High-dose methotrexate with or without whole brain radiotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma (G-PCNSL-SG-1): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1036–1047. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correa DD, DeAngelis LM, Shi W, Thaler H, Glass A, Abrey LE. Cognitive functions in survivors of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neurology. 2004;62(4):548–555. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000109673.75316.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavrilovic IT, Hormigo A, Yahalom J, DeAngelis LM, Abrey LE. Long-term follow-up of high-dose methotrexate-based therapy with and without whole brain irradiation for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4570–4574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freilich RJ, Delattre JY, Monjour A, DeAngelis LM. Chemotherapy without radiation therapy as initial treatment for primary CNS lymphoma in older patients. Neurology. 1996;46(2):435–439. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoang-Xuan K, Taillandier L, Chinot O, et al. Chemotherapy alone as initial treatment for primary CNS lymphoma in patients older than 60 years: a multicenter phase II study (26952) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2726–2731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omuro AM, Taillandier L, Chinot O, Carnin C, Barrie M, Hoang-Xuan K. Temozolomide and methotrexate for primary central nervous system lymphoma in the elderly. J Neurooncol. 2007;85(2):207–211. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izaks GJ, Westendorp RG, Knook DL. The definition of anemia in older persons. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1714–1717. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batchelor T, Carson K, O'Neill A, et al. Treatment of primary CNS lymphoma with methotrexate and deferred radiotherapy: a report of NABTT 96–07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1044–1049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC, Fisher B, Schultz CJ. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93–10. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(24):4643–4648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson DF, Martz KL, Bonner H, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the brain: can high dose, large volume radiation therapy improve survival? Report on a prospective trial by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG): RTOG 8315. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90538-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrey LE, Yahalom J, DeAngelis LM. Treatment for primary CNS lymphoma: the next step. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3144–3150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dees EC, O'Reilly S, Goodman SN, et al. A prospective pharmacologic evaluation of age-related toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2000;18(6):521–529. doi: 10.3109/07357900009012191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez H, Hidalgo M, Casanova L, et al. Risk factors for treatment-related death in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of a multivariate analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(6):2065–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrey LE, DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J. Long-term survival in primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(3):859–863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrlinger U, Kuker W, Uhl M, et al. NOA-03 trial of high-dose methotrexate in primary central nervous system lymphoma: final report. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(6):843–847. doi: 10.1002/ana.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien PC, Roos DE, Pratt G, et al. Combined-modality therapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: long-term data from a phase II multicenter study (Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreri AJ, Reni M, Foppoli M, et al. High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9700):1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omuro AM, Ben-Porat LS, Panageas KS, et al. Delayed neurotoxicity in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(10):1595–1600. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa DD, Rocco-Donovan M, DeAngelis LM, et al. Prospective cognitive follow-up in primary CNS lymphoma patients treated with chemotherapy and reduced-dose radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2009;91(3):315–321. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9716-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah GD, Yahalom J, Correa DD, et al. Combined immunochemotherapy with reduced whole-brain radiotherapy for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4730–4735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichtman SM. Guidelines for the treatment of elderly cancer patients. Cancer Control. 2003;10(6):445–453. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]