Abstract

Objectives

To develop an easily applicable diagnostic scoring method to determine the presence of peptic ulcers in dyspeptic patients in a primary care setting; to evaluate whether Helicobacter pylori testing adds value to history taking.

Design

Cross sectional study.

Setting

General practitioners' offices in the Utrecht area of the Netherlands.

Participants

565 patients consulting a general practitioner about dyspeptic symptoms of at least two weeks' duration.

Main outcome measures

The presence or absence of peptic ulcer; independent predictors of the presence of peptic ulcer as obtained from history taking and the added value of H pylori testing were quantified by using multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results

A history of peptic ulcer, pain on an empty stomach, and smoking were strong and independent diagnostic determinants of peptic ulcer disease, with odds ratios of 5.5 (95% confidence interval 2.6 to 11.8), 2.8 (1.0 to 4.0), and 2.0 (1.4 to 6.0) respectively. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC area) of these determinants together was 0.71. Adding the H pylori test increased the ROC area only to 0.75. However, in a group of patients at high risk, identified by means of a simple scoring rule based on history taking, the predictive value for the presence of peptic ulcer increased from 16% to 26% after a positive H pylori test.

Conclusions

In the total group of dyspeptic patients in primary care, H pylori testing has no value in addition to history taking for diagnosing peptic ulcer disease. In a subgroup of patients at high risk of having peptic ulcer disease, however, it might be useful to test for and treat H pylori infections.

What is already known on this topic

In primary care, predicting the presence of peptic ulcer disease in dyspeptic patients on the basis of history taking is difficult

Infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with peptic ulcer disease

Many non-invasive H pylori tests are available, but the value they add to history taking is not known

What this paper adds

Three simple questions from history taking can distinguish between patients at high and low risk of peptic ulcer disease

In uninvestigated patients with dyspepsia in primary care, H pylori testing adds nothing to optimal history taking in the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease

In patients at high risk of peptic ulcer disease it is useful to test for and treat H pylori infection

Introduction

Dyspepsia is a common problem.1 The vast majority of patients presenting with dyspepsia in primary care have no organic disease, but a few patients have peptic ulceration and would benefit from specific treatment—notably, those whose ulcer is related to Helicobacter pylori infection.2 Although the number of peptic ulcers unrelated to H pylori is increasing, most ulcers are related to H pylori infection, which accounts for significant morbidity and mortality.3,4 Non-invasive “test and treat” policies for H pylori infection have been promoted in order to improve early detection and treatment of ulcers in dyspeptic patients.5–10In a recently published systematic review, Moayyedi et al stated that eradication of H pylori is also of modest benefit in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia.11 This benefit, however, seems too small to make promotion of test and treat strategies for H pylori for all dyspeptic patients advisable (15 patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia need to receive H pylori eradication therapy to reduce dyspepsia in one patient). Furthermore, although a test and treat strategy or the alternative strategy of direct endoscopy in all dyspeptic patients may be cost effective, this cost effectiveness would be reduced in the primary care setting, with its lower prevalence of peptic ulcers.12 In addition, a strategy involving routine endoscopy would be a considerable burden to patients.

Many dyspepsia guidelines, including those of the Dutch College of General Practitioners, still recommend restricting H pylori eradication to patients with a proved peptic ulcer.13Thus preselection by general practitioners, based on symptoms and signs, of dyspeptic patients at increased risk of having peptic ulcer disease remains crucial. So far, such symptom based diagnostic algorithms for predicting the presence of peptic ulcer have performed rather poorly, although the statistical power of most studies was limited.14–22 Furthermore, the value of a diagnostic method combining optimal history taking with additional H pylori testing has not been explored.

We carried out a diagnostic study to determine which components of history taking independently contribute to predicting the presence of peptic ulcer disease in patients with dyspepsia presenting to general practice and whether H pylori testing provides any added diagnostic value. In addition, we aimed to develop an easily applicable scoring system to aid the diagnosis of peptic ulcer in primary care.

Methods

Data were obtained from three different studies performed at the University Medical Center, Utrecht, with similar inclusion and exclusion criteria, in primary care patients with dyspeptic symptoms who were referred to open access endoscopy facilities in the greater Utrecht area between June 1996 and January 2000. Participants were eligible for this diagnostic study if they had had dyspeptic symptoms for at least two weeks before visiting their general practitioner. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant; presented with weight loss, anaemia, dysphagia, gastric bleeding, or vomiting; or had previous gastric surgery.

Diagnostic procedures

Age, sex, medical history, smoking behaviour, comorbidity, medication, and current symptoms were recorded by the general practitioner on a standard form. The H pylori status of all patients was subsequently determined with at least one of the following tests: a whole blood test (BM-Test Helicobacter pylori; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), an enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (Pyloriset EIA-G; Orion Diagnostics, Espoo, Finland), and a carbon-13 urea breath test (Pylobactell; BSIA/Torbett Laboratories, Chatham, UK). If one of these tests had positive results, the patient was considered to be infected with H pylori. Finally, all patients were referred for endoscopy in one of the participating centres to establish a diagnosis. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center, Utrecht, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Outcome definition

The outcome of the study was the presence or absence of peptic ulcer disease. A peptic ulcer was considered to be present when a duodenal or gastric ulcer, erosive gastritis, or duodenitis was detected endoscopically.

Data analysis

The (univariate) association between each potential diagnostic determinant obtained from history taking and the presence of peptic ulcer disease was quantified by using odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. All determinants with P<0.25 were then entered together in a multivariate logistic regression model to evaluate which were independently associated with the presence of peptic ulcer disease. The model was reduced by excluding variables with P>0.05 in order to retain a simpler diagnostic model containing only the strongest determinants of the presence of peptic ulcer disease.

This reduced model was extended with the H pylori test result to quantify the added value of the test result in predicting the presence or absence of peptic ulcer disease. The reliability (goodness of fit) of each of the diagnostic models was assessed by using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test,23 and the ability to discriminate between patients with and without peptic ulcer was quantified by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC area).24 The ROC area is a suitable measure to summarise the discriminative power of a diagnostic model and can range from 0.5 (no discrimination, like flipping a coin) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination). A value of 0.7-0.8 is considered to represent reasonable discrimination, and a value of >0.8 is good discrimination.25Differences in diagnostic discriminative value between different (reduced and extended) models were estimated by comparing ROC areas, taking into account the correlation between the models as they were based on the same cases.26,27

Subgroup analyses

We analysed the ability of subsets of relevant diagnostic determinants obtained from history taking to detect peptic ulcer disease. Taking into account the independent diagnostic determinants, we identified groups of patients at high and low risk by using the odds ratios of the history model. The added value of a non-invasive H pylori test in detecting peptic ulcer disease in these subgroups was assessed by creating two by two tables and computing the χ2 statistic and the posterior probability of a peptic ulcer following positive and negative H pylori tests.

Results

Complete data on medical history, current symptoms, and the diagnosis according to endoscopy were available for 565 of the 612 patients enrolled in the study (tables 1 and 2). Of these 565 patients, 38 (6.7%) had a peptic ulcer detected at endoscopy. The peptic ulcers were related to H pylori according to the non-invasive H pylori test in 22 (58%) of these 38 patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with dyspepsia in primary care with and without peptic ulcer (n=565). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Peptic ulcer (n=38) | No peptic ulcer (n=527) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.3 | 45.3 | 0.67 |

| Male sex | 21 (55) | 244 (46.3) | 0.32 |

| Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 3 (8) | 106 (20.1) | 0.32 |

| Hiatal hernia | 1 (3) | 50 (9.5) | 0.24 |

| Pain after meal | 15 (40) | 261 (49.5) | 0.24 |

| Obstruction | 9 (24) | 133 (25.2) | 0.84 |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 14 (37) | 40 (7.5) | <0.01 |

| Smoking | 20 (53) | 170 (32.3) | 0.013 |

| Pain on empty stomach | 27 (71) | 237 (45.0) | 0.002 |

| Use of H2 antagonist | 16 (42) | 192 (36.4) | 0.48 |

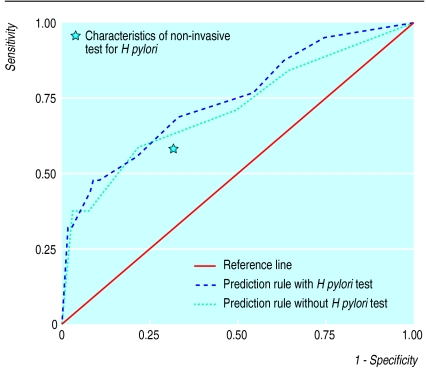

Age, history of peptic ulcer disease, smoking, pain on empty stomach, and the non-invasive H pylori test were associated with the presence or absence peptic ulcer disease and were selected for multivariate analyses (table 3). Of the four history variables, smoking, pain on an empty stomach, and history of peptic ulcer disease were independent predictors of peptic ulcer disease. The ROC area of the history model based on these three items was 0.71 (95% confidence interval 0.62 to 0.81). Adding the non-invasive H pylori test to the model increased the ROC area to 0.75 (0.66 to 0.83) (figure). This increase was not significant (P=0.46). Both models had sufficient goodness of fit. Although the H pylori test result was independently associated with the presence or absence of peptic ulcer disease in the total patient group, as indicated by the odds ratios with 95% confidence interval in table 3, it did not contribute to a better discrimination beyond history taking, as indicated by the small increase in ROC area.

Table 3.

Relation between history variables and presence of peptic ulcer disease in 565 patients presenting with dyspepsia in primary care

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced model | Reduced model plus Helicobacter pylori test | ||

| Age per year | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | Not included | Not included |

| Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 0.3 (0.04 to 2.3) | Not included | Not included |

| Hiatus hernia | 0.3 (0.03 to 1.9) | Not included | Not included |

| Pain after meal | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) | Not included | Not included |

| Obstruction | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | Not included | Not included |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 6.4 (3.1 to 13.5) | 5.5 (2.6 to 11.8) | 4.6 (2.1 to 10.1) |

| Smoking | 2.2 (1.2 to 4.3) | 2.0 (1.0 to 4.0) | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.8) |

| Pain on empty stomach | 3.0 (1.5 to 6.2) | 2.8 (1.4 to 6.0) | 2.8 (1.3 to 5.9) |

| Non-invasive test for H pylori | 3.1 (1.6 to 6.0) | Not included | 2.7 (1.4 to 5.5) |

We went on to estimate the value of H pylori testing in subgroups of patients at high or low risk of peptic ulcer disease, based on history taking. Using the odds ratios in table 3, a scoring method was developed, including history of peptic ulcer disease (weight=2) and smoking and pain on empty stomach (both weight=1). High risk was defined as a score of ⩾2 and low risk as <2; 135 patients at high risk and 430 patients at low risk were identified. The prior probability (prevalence) of peptic ulcer disease was 16% (22/135) in the high risk group and 4% (16/430) in the low risk group (table 4). In the high risk group, a positive H pylori test result increased the probability (positive predictive value) from 16% to 26% (14/54). A negative test result decreased the probability (negative predictive value) from 16% to 10% (8/81). In the low risk group, the positive predictive value was 7% and the negative predictive value was 2.5%.

Table 4.

Result of non-invasive Helicobacter pylori testing and presence of peptic ulcer disease in 565 dyspeptic patients in primary care categorised as being at a high or low risk of peptic ulcer disease. Values are numbers of patients

| H pylori infection | High risk†

|

Low risk‡

|

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer | No peptic ulcer | Peptic ulcer | No peptic ulcer | |||

| Yes | 14 | 40 | 8 | 112 | 174 | |

| No | 8 | 73 | 8 | 302 | 391 | |

| Total | 22 | 113 | 16 | 414 | 565 | |

Group at high risk (two or more points according to the scoring method) contains patients with a history of peptic ulcer or smoking and pain before meals or a history of peptic ulcer, smoking, and pain before meals.

Group at low risk contains all participants not included in the group at high risk.

Discussion

Our study indicates that H pylori testing in all patients with dyspepsia in primary care has no value in addition to history taking for the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease. However, in a subgroup of patients at high risk of peptic ulcer disease (based on scoring including the three history variables of smoking, pain on empty stomach, and history of peptic ulcer), a non-invasive H pylori test provides additional diagnostic information as indicated by relevant post-test changes in the probability of the presence or absence of peptic ulcer disease.

Applying a test and treat strategy (performing a non-invasive H pylori test, initiating eradication therapy in patients with a positive result, and providing acid suppressive therapy to the remaining patients) in all patients presenting with dyspepsia in primary care would lead to prescription of eradication therapy in up to 31% of all patients, whereas a peptic ulcer is present in only 12.6% of these. This would lead to unnecessary costs and potential side effects, including the development of resistance to antibiotics. Restriction of non-invasive H pylori testing to patients preselected as being at high risk according to our scoring rule based on history variables seems a more appropriate recommendation. The risk of these patients having a peptic ulcer is considerable (16.3%), and peptic ulcer treatment could be initiated without prior endoscopy. An H pylori test and treat strategy in high risk patients would result in prescription of eradication therapy in only 9.6% of all dyspeptic patients, 26% of whom would have a peptic ulcer. In this high risk group, the ratio of patients “correctly” (those with peptic ulcer) or “incorrectly” (those without peptic ulcer) receiving eradication therapy is 1:3, whereas the corresponding ratio in the total group of dyspeptic patients presenting in primary care is 1:7.

Moayyedi et al reported in a recent systematic review that an early H pylori test and treat strategy might be cost effective in non-ulcer dyspepsia, and Lassen et al concluded from their own research that a test and treat strategy is as efficient and safe as prompt endoscopy for the management of dyspeptic patients in primary care.11,12 We believe that both groups failed to recognise the benefit of preselection of patients by adequate history taking before H pylori testing is considered and that implementation of their recommendations would result in many unjustified prescriptions for eradication of H pylori.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study need to be addressed. Our analyses were based on data from three previous studies by our group. As a result, different H pylori tests with varying characteristics were used. This might have accounted for an underestimation of H pylori infections and peptic ulcers related to H pylori.28,29 This is confirmed by the fact that the rate of H pylori infection found at endoscopy in our patients (by culture, histology, or rapid urease testing of biopsy specimens) was higher (41%) than the rate found with non-invasive tests (31%). Use of more reliable non-invasive test methods would have led to more peptic ulcers related to H pylori being detected, which would have improved the performance of our scoring method. The scoring method awaits prospective evaluation in other primary care populations; the performance of the scoring method critically depends on the prevalence of H pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease. Currently, the rule is being tested by several groups of general practitioners in the Netherlands.

Conclusions

We conclude that adding testing for H pylori infection to history taking might be useful only in patients at high risk of having peptic ulcer disease. It would avoid endoscopies in some patients and lead to more accurate treatment of peptic ulcer disease in most patients.

Table 2.

Endoscopic diagnosis of 565 patients presenting with dyspepsia to their general practitioner and included in the decision method

| Endoscopic diagnosis | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Malignancy of gastrointestinal tract | 4 (0.7) |

| Gastric ulcer | 5 (0.9) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 33 (5.8) |

| Mucosal damage* | 214 (37.9) |

| Other relevant disease† | 5 (0.9) |

| Minor disease‡ | 179 (31.7) |

| No abnormalities | 125 (22.1) |

Oesophagitis, bulbitis, severe gastritis.

Achalasia, polyps, Schatzki's ring, oesophagus varices.

Hiatus hernia, gastro-oesophageal prolapse, chronic gastritis.

Figure.

Receiver operating characteristic curves from multivariate logistic regression analyses including the three diagnostic determinants for peptic ulcer disease (history of peptic ulcer, smoking, and pain on empty stomach) with or without additional non-invasive testing for Helicobacter pylori. The area under the curve without H pylori testing is 0.71 (SE 0.05); the area under the curve with H pylori testing is 0.75 (0.05)

Acknowledgments

We thank Roche Diagnostics (Almere, Netherlands) and the Imphos/Zambon group (Amersfoort, Netherlands) for supplying the whole blood tests and ELISAs and Peter Zuithoff for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Funding: research grant from the Dutch Health Care Insurance Council.

Competing interests: CFW has received reimbursement for attending symposia from AstraZeneca, Abbott, and Janssen-Cilag. NJW and MEN have received reimbursements for attending symposia, fees for organising postgraduate education, and funds for research from AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, BykGulden, Abbott, and GlaxoWellcome. AJPMS has received funding for research and organising postgraduate education from AstraZeneca, BykGulden, Janssen-Cilag, GlaxoWellcome, Ferring, Aventis, Novartis, and Solvay. TJMV has received reimbursement for attending symposia from Abbott.

References

- 1.Jones R, Lydeard S. Prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in the community. BMJ. 1989;298:30–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heikkinen M, Pikkarainen P, Takala J, Rasanen H, Julkunen R. Etiology of dyspepsia: four hundred unselected consecutive patients in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:519–523. doi: 10.3109/00365529509089783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciociola AA, McSorley DJ, Turner K, Sykes D, Palmer JB. Helicobacter pylori infection rates in duodenal ulcer patients in the United States may be lower than previously estimated. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1834–1840. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boer WA, Joosen EA. Disease management in ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;230(suppl):23–28. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser AG, Ali MR, McCullough S, Yeates NJ, Haystead A. Diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori—can they help select patients for endoscopy? N Z Med J. 1996;109:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobbs FD, Delaney BC, Rowsby M, Kenkre JE. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on dyspeptic symptoms in primary care. Fam Pract. 1996;13:225–228. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asante MA, Patel P, Mendall M, Jazrawi R, Northfield TC. The impact of direct access endoscopy, Helicobacter pylori near patient testing and acid suppressants on the management of dyspepsia in general practice. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moayyedi P, Zilles A, Clough M, Hemingbrough E, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. The effectiveness of screening and treating Helicobacter pylori in the management of dyspepsia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1245–1250. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones R, Tait C, Sladen G, Weston-Baker J. A trial of a test-and-treat strategy for Helicobacter pylori positive dyspeptic patients in general practice. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joosen EA, Reininga JH, Manders JM, ten Ham JC, de Boer WA. Costs and benefits of a test-and-treat strategy in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects: a prospective intervention study in general practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:319–325. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Forman D, Mason J, Innes M, et al. Systematic review and economic evaluation of Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment for non-ulcer dyspepsia. BMJ. 2000;321:659–664. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassen AT, Pedersen FM, Bytzer P, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Helicobacter pylori test-and-eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Numans ME, de Wit NJ, Geerdes RHM, Muris JWM, Starmans R, Postema PhJ, et al. Dutch College of General Practitioners' guidelines on dyspepsia. Huisarts Wet. 1996;39:565–577. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bytzer P, Hansen JM, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Malchow-Moller A. Predicting endoscopic diagnosis in the dyspeptic patient. The value of predictive score models. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:118–125. doi: 10.3109/00365529709000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannessen T, Petersen H, Kleveland PM, Dybdahl JH, Sandvik AK, Brenna E, Waldum H. The predictive value of history in dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:689–697. doi: 10.3109/00365529008997594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Numans ME, Van der Graaf Y, de Wit NJ, Touw-Otten F, de Melker RA. How much ulcer is ulcer-like? Diagnostic determinants of peptic ulcer in open access gastroscopy. Fam Pract. 1994;11:382–388. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muris JW, Starmans R, Pop P, Crebolder HF, Knottnerus JA. Discriminant value of symptoms in patients with dyspepsia. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laheij RJ, Severens JL, Jansen JB, van de Lisdonk EH, Verbeek AL. Management in general practice of patients with persistent dyspepsia. A decision analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:563–567. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199712000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen JM, Bytzer P, Schaffalitzky De Muckadell OB. Management of dyspeptic patients in primary care. Value of the unaided clinical diagnosis and of dyspepsia subgrouping. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:799–805. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanghellini V, Barbara G, Salvioli B, Corinaldesi R, Tosetti C. Management of dyspepsia in primary care. Dyspepsia subgroups are useful in determining treatment. BMJ. 1998;316:1388–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crean GP, Holden RJ, Knill-Jones RP, Beattie AD, James WB, Marjoribanks FM, Spiegelhalter DJ. A database on dyspepsia. Gut. 1994;35:191–202. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiegelhalter DJ, Crean GP, Holden R, Knill-Jones RP. Taking a calculated risk: predictive scoring systems in dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;128(suppl):152–160. doi: 10.3109/00365528709090984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1989. pp. 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinstein MC, Fineberg HV. Clinical decision analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148:839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quartero AO, Numans ME, de Melker RA, de Wit NJ. In-practice evaluation of whole-blood Helicobacter pylori test: its usefulness in detecting peptic ulcer disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones R, Phillips I, Felix G, Tait C. An evaluation of near-patient testing for Helicobacter pylori in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:101–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.125296000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]