Abstract

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations are presented on biomimetic model complexes of cysteine dioxygenase and focus on the effect of axial and equatorial ligand placement. Recent studies of one of us [Y. M. Badiei, M. A. Siegler and D. P. Goldberg, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1274] gave evidence of a nonheme iron biomimetic model of cysteine dioxygenase using an i-propyl-bis(imino)pyridine, equatorial tridentate ligand. Addition of thiophenol, an anion – either chloride or triflate – and molecular oxygen, led to several possible stereoisomers of this cysteine dioxygenase biomimetic. Moreover, large differences in reactivity using chloride as compared to triflate as the binding anion were observed. Here we present a series of DFT calculations on the origin of these reactivity differences and show that it is caused by the preference of coordination site of anion versus thiophenol binding to the chemical system. Thus, stereochemical interactions of triflate and the bulky iso-propyl substituents of the ligand prevent binding of thiophenol in the trans position using triflate. By contrast, smaller anions, such as chloride, can bind in several ligand positions and give isomers with similar stability. Our calculations explain the observance of thiophenol dioxygenation by this biomimetic system and give details of the reactivity differences of ligated chloride versus triflate.

Introduction

Nonheme iron enzymes are versatile oxidants that catalyze a range of vital processes for human health, and are involved in repair mechanisms, biosynthesis as well as biodegradation of compounds. Generally, they use molecular oxygen on an iron center and transfer either one or both oxygen atoms of molecular oxygen to a substrate, whereby a monoxygenation, dioxygenation or dehydrogenation type of reaction occurs. Nature has developed a large arsenal of these nonheme iron enzymes with various differences in ligand orientation and binding as well as functional properties.1 Studies on nonheme iron containing enzymes and synthetic analogues (biomimetic compounds) are important for the understanding of biochemical reaction mechanisms but also for industrial (biotechnological) applications.

An extensively studied class of nonheme iron enzymes is the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases, which anchor the metal via a facial 2-His-1-Asp ligand orientation to the protein.2 These enzymes catalyze the biosynthesis of several antibiotics in bacteria; including vancomycin, fosfomycin and carbapenem.3 In addition, these enzymes have been implicated with DNA and RNA repair mechanisms.4 A structurally similar enzyme to the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases is the human enzyme cysteine dioxygenase (CDO), which is involved in the detoxification and metabolism of cysteine in the body.5 It catalyzes the first step in the biodegradation of cysteine and converts the substrate to cysteine sulfinic acid. This is a unique reaction and of interest to the biotechnology industry for the catalytic dioxygenation of sulphides.

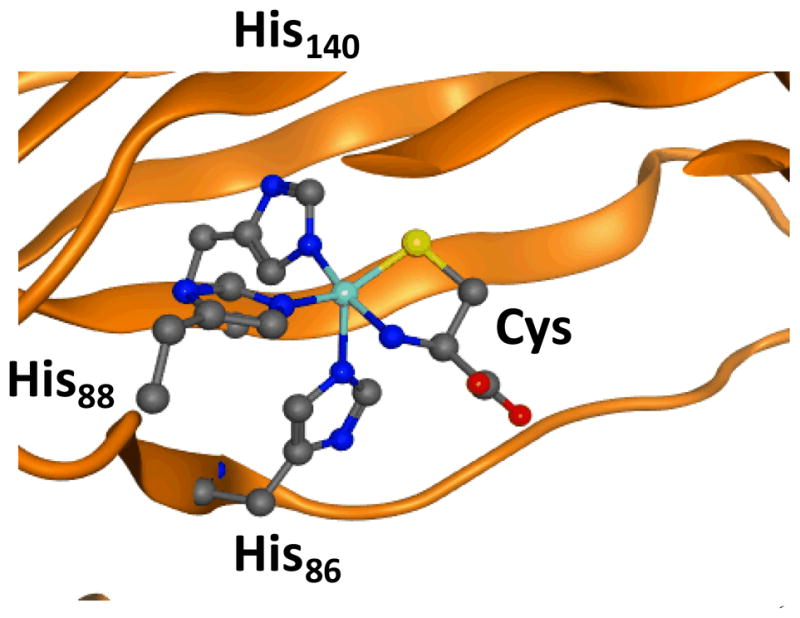

CDO contains an unusual ligand system where the metal is bound to three histidine ligands of the protein via a 3-His facial ligand orientation, but compared to the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases lacks the carboxylate ligand and the 2-His/1-Asp motif. Current evidence suggests the substrate cysteinate binds the metal in a bidentate fashion through the thiolate and amine groups and is locked in hydrogen bonding interactions via several nearby polar amino acids. Fig 1 displays the active site of substrate bound CDO as taken from the 2IC1 protein databank (pdb) structure.6 Similar to the nonheme iron dioxygenases, the protein binds the metal in a facial orientation and the ligand position trans to His86 is vacant and is reserved for molecular oxygen. In recent years a number of spectroscopic and kinetic studies have provided important insight on the catalytic mechanism of CDO, but there is little knowledge of oxygen bound intermediates.7 A series of computational studies in our groups have given insight into the CDO ligand system and its mechanism of substrate activation.8 These studies showed that replacing the 3-His ligand system of CDO by a 2-His-1-Asp ligand system disrupts the dioxygenation process of cysteine and, in particular, leads to weakening of the Fe–S bond. It appears, therefore, that the 3-His ligand system is essential for optimal dioxygenation of cysteine.

Fig 1.

Extract of the active site of CDO as taken from the 2IC1 pdb file.6

Amino acids are labelled as in the pdb

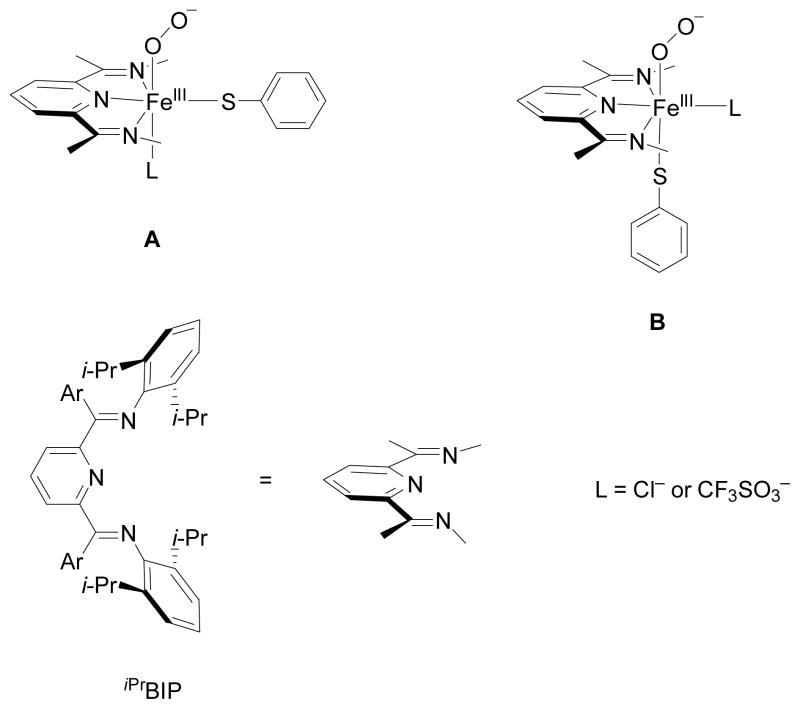

In biomimetic chemistry, active site analogues are created with the aim to understand the basic features of enzyme active site structures.1c,1d,9 Recently, a few biomimetic models of CDO enzymes were published and spectroscopically characterized.10–12 One of these contains an Fe(II)(iPrBIP) complex (iPrBIP = iso-propyl-bis(imino)pyridine), Scheme 1.11 Studies focused on the relative orientation of thiophenol and dioxygen on the metal center. Thus, the iPrBIP ligand occupies three ligand positions of the metal in the same plane. Dioxygen will occupy the ligand position cis with respect to the three nitrogen atoms of the iPrBIP ligand. The remaining two ligand positions are occupied by thiophenolate (SPh−) and an anion, which is either Cl− or CF3SO3−. Consequently, these complexes have two possible stereoisomers (Scheme 1) for the Fe(III)-superoxo complex, i.e. [FeIIIO2(iPrBIP)(SPh)(L)] with L = Cl− or CF3SO3− (OTf−), which are designated with A and B in Scheme 1, respectively. It also should be noted that in contrast to the facial triad of histidine ligands in CDO enzymes, the iPrBIP ligand coordinates in one plane thereby leaving the axial ligand position vacant for either substrate or an anion. The previous experimental studies revealed dramatic differences in reactivity that were induced by changing the ligand L from Cl− to CF3SO3−, whereby the chloride ligated complex gave disulfide products, whereas the triflate ligated system reacted with O2 to give an S-oxygenated sulfonato product.11 These differences were assigned to axial versus equatorial ligand effects on the iron complex, however, direct evidence for this mechanistic hypothesis was lacking. To gain insight into this matter we performed a density functional theory (DFT) study, and the results are present here.

Scheme 1.

Models investigated in this study.

The effect of axial and equatorial ligands on heme and nonheme iron oxidants is well documented. Thus, heme monoxygenases such as the cytochromes P450 contain an iron-heme active center where the heme is linked to the protein via an axial cysteinate ligand.13 By contrast, heme peroxidases have an axially ligated histidine group, which has been proposed to be a key reason for their differences in catalytic function.14 These studies proposed the cysteinate to act with a “push”-effect and the push/pull-effect of the axial ligand is thought to contribute to the reactivity differences of P450s vis-à-vis peroxidases. Indeed, a series of density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirmed that peroxidase models reacted with much higher barriers in aliphatic hydroxylation and epoxidation reactions using the same substrate.15 Moreover, the differences between an axially ligated cysteinate versus histidine were explained as originating from the charge of the axial ligand and the molecular orbital interactions between metal and ligand.16

In biomimetic models, the effect of the axial ligand on spectroscopic properties (trans-influence) as well as on reactivity patterns (trans-effect) was demonstrated by Gross and coworkers17 using studies of styrene epoxidation by a range of iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin cation radical systems. Subsequent studies of Nam et al18 showed differences in oxidative properties of iron(IV)-oxo oxidants with chloride trans to the oxo group as compared to those with acetonitrile, leading to reactivity differences of those oxidants with cis versus trans olefins, the regioselectivity of aliphatic over aromatic hydroxylation, as well as epoxidation versus hydroxylation processes. Further studies also revealed axial ligand effects on the reactivity and spectroscopic parameters of a selection of nonheme iron complexes,19 including a series of thiolate-ligated nonheme iron model complexes by one of us.20 Recent, combined experimental and computational studies in our groups on the reactivity of manganese(V)-oxo embedded in a corrolazine ligand system identified a pronounced axial ligand effect on the rate constant of hydrogen atom abstraction from C–H substrates (e.g. dihydroanthracene) as a function of the axial ligand.21 By contrast, very little is known of the ligand effect of iron(III)-superoxo complexes, which we will address in this work. The computational study presented here provides insight into the equatorial and axial ligand effect of the CDO biomimetic model displayed in Scheme 1.

Methods

The studies presented in this work use density functional theory methods as implemented in the Gaussian-03 program package.22 Following previous experience in the field,23 we initially used the unrestricted hybrid density functional method UB3LYP24 in combination with a double-ζ quality LANL2DZ basis set on iron that includes a core potential and 6-31G on the rest of the atoms,25 basis set BS1. We performed a full geometry optimization (without constraints) followed by an analytical frequency calculation. All structures were confirmed as local minima and had no imaginary frequencies. Subsequent geometry optimization and frequency calculations were done with a triple-ζ quality basis set: BS2 represents a triple-ζ LACV3P+ basis set on iron and 6-311+G* on the rest of the atoms and BS3 is 6-311+G* on all atoms. It should be noted that very little differences in energy and optimized geometries are obtained between UB3LYP/BS2//UB3LYP/BS1 calculations as compared to those found for UB3LYP/BS2 optimizations, therefore, we will focus on the latter results only in this paper.26 All calculations were done for the lowest lying singlet, triplet, quintet and septet spin states To test the effect of the environment on the ordering and relative energies of the various spin states, we did single point calculations using the polarized continuum model (PCM) with a dielectric constant of ε = 35.7 mimicking an acetonitrile solution at UB3LYP/BS2.

To confirm the obtained spin state ordering and relative energies we did a further set of calculations using dispersion corrected density functional theory (B3LYP-D).27 We reoptimized 3,5,7AL and 3,5,7BL (L = Cl−/OTf−) at B3LYP-D/BS1 level of theory followed by a single point calculation at B3LYP-D/BS2 level of theory. The methods used in this work are well tested and benchmarked, for example, they have been used to reproduce experimental free energies of activation of oxygen atom transfer processes within about 3 kcal mol−1.28

Results and Discussion

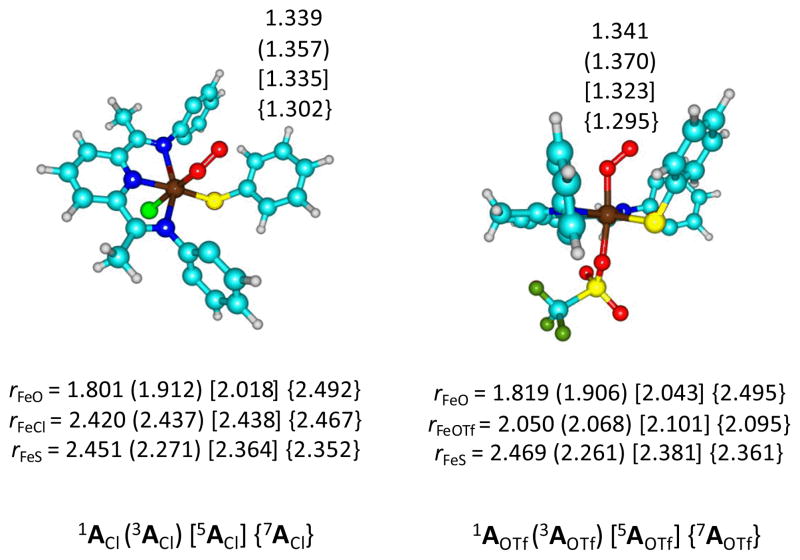

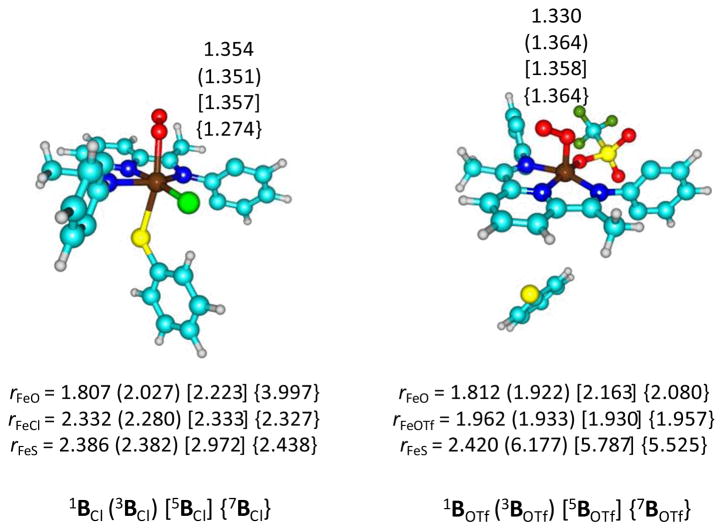

We started our investigation with a series of calculations on 1,3,5,7AL (L = Cl− and OTf−) and the optimized geometries are given in Fig 2, whereas the relative energies of the individual spin states are given in Table 1. The method has very little effect on the spin state ordering, which is virtually constant for all models described in this work. Generally, the septet and triplet spin states are destabilized with dispersion corrections included. Nevertheless, the results appear to give close lying quintet and septet spin iron(III)-superoxo intermediates.

Fig 2.

Optimized geometries of 1,3,5,7ACl (left-hand-side) and 1,3,5,7AOTf (right-hand-side) with bond lengths in angstroms. H-atoms and isopropyl groups have been hidden.

Table 1.

Spin state ordering and relative energies of 1,3,5,7AL and 1,3,5,7BL (L = Cl−/OTf−) as obtained using different methods and techniques. All data are in kcal mol−1 and include zero-point corrections. Esolv stands for solvent corrected energy.

| B3LYP/BS1 | B3LYP/BS2 | B3LYP+Esolv/BS2 | B3LYP-D/BS1 | B3LYP-D/BS2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1ACl | 26.05 | 25.55 | 32.00 | ||

| 3ACl | 12.56 | 11.73 | 16.13 | 27.16 | 39.19 |

| 5ACl | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7ACl | −0.27 | −8.11 | −2.66 | −0.11 | 0.21 |

| 1AOTf | 26.16 | 31.84 | 32.36 | ||

| 3AOTf | 5.94 | 11.47 | 11.31 | 18.50 | 31.27 |

| 5AOTf | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7AOTf | −0.55 | −1.91 | −2.41 | 0.65 | 1.46 |

| 1BCl | 29.73 | 28.18 | 32.72 | ||

| 3BCl | 10.72 | 9.42 | 15.49 | 24.58 | 35.71 |

| 5BCl | 2.62 | 1.16 | 7.46 | 20.96 | 12.15 |

| 7BCl | −7.56 | −18.40 | −11.75 | −7.55 | −9.21 |

| 1BOTf | 37.05 | 41.67 | 37.51 | ||

| 3BOTf | 19.70 | 31.24 | 26.60 | 61.03 | 75.68 |

| 5BOTf | 15.03 | 23.73 | 20.15 | 43.55 | 39.19 |

| 7BOTf | 5.09 | 9.16 | 5.03 | 27.42 | 33.90 |

We, generally, find minor structural differences between geometries optimized at UB3LYP/BS1 (Fig 2) and UB3LYPD/BS1 (Fig S3, Electronic Supporting Information) level of theory for most key intermediates. In both cases the quintet and septet spin states are degenerate, whereby the septet state is the lowest by a few kcal mol−1 at B3LYP but dispersion corrections make the quintet slightly lower in energy. The triplet (singlet) spin states are well higher in energy by 19.8 (33.7) kcal mol−1 for ACl and 13.4 (33.8) kcal mol−1 for AOTf, therefore, therefore we conclude that these two spin states are unlikely to play a role of importance in the reaction mechanism. With dispersion corrections included these spin states are further raised in energy. Recent spectroscopic studies on a synthetically generated iron(III)-superoxo CDO intermediate found evidence of a septet spin ground state.29 Although these enzymatic CDO studies contradict other nonheme iron(III)-superoxo work,30 where quintet spin ground states are found, the work does support the calculations presented here. Consequently, the availability of a low-lying septet spin state may be inherent to the ligand system of CDO enzymes and their biomimetic model complexes. However, these results do not require that the reactivity take place on the septet spin state surface, as will be seen later.

Optimized geometries are in line with previous computational studies on Fe(III)-superoxo complexes that typically find O–O distances in the range of 1.295 – 1.370 Å.31 The Fe–Cl distance is in a narrow range from 2.420 – 2.467 Å, which is in good agreement with previous studies of iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin cation radical systems that also had an axially ligated Cl− anion.32 There is some fluctuation in the Fe–S bond length between the four different spin states, however, this follows from the molecular orbital occupations, vide infra.

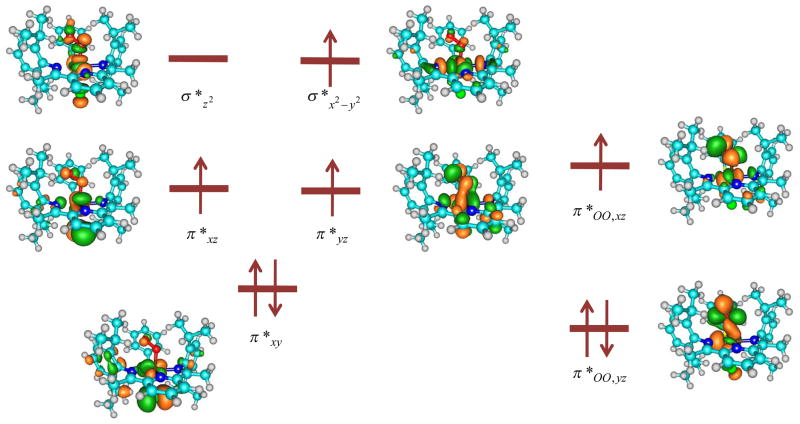

To understand these spin state energetics and the differences between models ACl and AOTf, consider in Fig 3 the high-lying occupied and virtual orbitals for both systems as taken from the quintet spin calculations. The metal-type orbitals originate from a linear combination of the 3d atomic orbitals on iron with ligand based orbitals. The lowest lying orbital is the π*xy orbital that is in the plane of the iPrBIP ligand. A bit higher in energy are the π*xz and π*yz orbitals; the former is in the plane of the Fe–O–O group and interacts with a π-orbital on the axial ligand, while the π*yz orbital interacts with both the axial ligand and the proximal oxygen atom. Higher in energy are two σ* orbitals: one for the antibonding interaction of the axial ligand and the proximal oxygen atom with the iron (σ*z2) and the second for the antibonding interactions of the metal with the BIP and phenylthiolate ligands (σ*x2–y2). Two antibonding orbitals along the superoxo bond are also depicted in Fig 3 (π*OO,yz and π*OO,xz), which are occupied with three electrons. The metal-based orbitals are occupied with five electrons, and the system is characterized as an Fe(III)-superoxo complex with a quintet spin state.

Fig 3.

High-lying occupied and low-lying virtual orbitals of 5ACl.

The quintet spin state has orbital occupation π*xy2 π*xz1 π*yz1 σ*x2–y21 π*OO,yz2 π*OO,xz1 and includes the ferromagnetic coupling of the π*OO,xz electron with three metal based unpaired electrons. The lowest lying triplet spin state, by contrast, has π*xy2 π*yz2 π*xz1 π*OO,yz2 π*OO,xz1 and is distinguished from the quintet spin state by the transfer of one electron from σ*x2–y2 to π*yz. This conversion is equivalent to a change from intermediate-spin FeIII to a low-spin FeIII ion.

Both of these states, therefore, can be characterized as Fe(III)-superoxo complexes. The singlet and septet spin states, by contrast, are Fe(II)-dioxygen complexes with orbital occupation π*xy2 π*xz1 π*yz1 σ*x2–y21 σ*z21 π*OO,yz1 π*OO,xz1 and π*xy2 π*xz2 π*yz2 π*OO,yz2, respectively. We made several attempts to swap orbitals for the singlet spin state and calculate a low-spin Fe(III)-superoxo complex but all our calculations converged back to the Fe(II)-dioxygen situation instead. It appears therefore that there is no lower lying low-spin state for these complexes. The orbital occupation is in line with previous experimental and computational studies of six-coordinate iron(III)-superoxo complexes.30,33,34

The pentacoordinated iron(II)-iPrBIP(X) reactant complex with X = Cl− or OTf− was characterized as a quintet spin state,11 therefore, dioxygen binding may continue on the quintet spin state surface rather than generating a septet spin iron(II)-peroxo state. In light of the large geometric differences between the quintet and septet structures, this would imply small spin-orbit coupling between the two states and little equilibration between the two spin states. Our optimized geometries are also in support of the orbital occupations, and, for instance, in the quintet spin state due to single occupation of a σ*x2–y2 orbital with antibonding character along the Fe–SPh axis, the Fe–S distances are elongated with respect to the triplet spin state, where this orbital is virtual. The same trend is also observed for 1,3,5,7AOTf. On the other hand, occupation of the σ*z2 orbital in the quintet spin state would have elongated the Fe–O and Fe-axial ligand distances considerably, as observed before.35 The geometries, therefore, support the assignment of a singly occupied σ*x2–y2 orbital and virtual σ*z2 orbital in the quintet spin states.

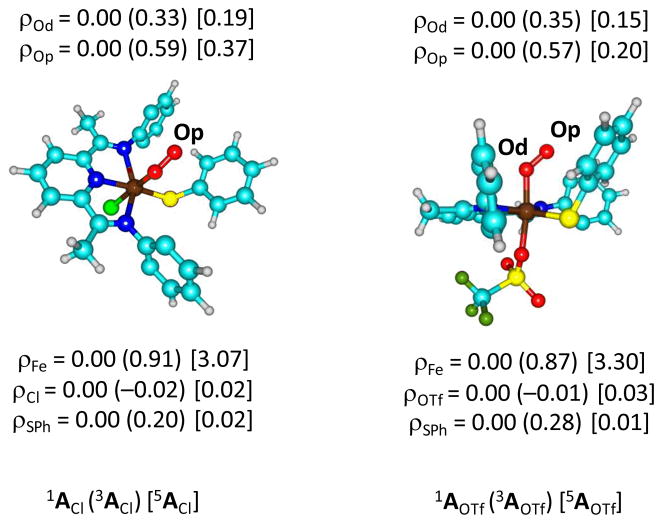

The group spin densities (Fig 4) give further evidence for the assignment of the orbital occupations discussed above. In the triplet spin state the unpaired spin density on the superoxo group is 0.92 for both 3ACl and 3AOTf, which is coupled to an unpaired electron on the metal; the spin density on iron is 0.91 in 3ACl and 0.87 in 3AOTf. These spin densities confirm the single occupation of the π*xz and π*OO,xz orbitals in these triplet spin states. In the quintet spin states, by contrast, the metal unpaired spin density is increased to 3.07 and 3.30 for 5ACl and 5AOTf, respectively. The metal is involved in all four singly occupied molecular orbitals, although the contribution is small in π*OO,xz (Fig 3). In the quintet spin states there is also significant spin density on the BIP ligand system (0.30 in 5ACl and 0.33 in 5AOTf), which further supports the assignment of a singly occupied σ*x2–y2 orbital.

Fig 4.

Group spin densities calculated at UB3LYP/B2//UB3LYP/B1 for 1,3,5,7ACl (left-hand-side) and 1,3,5,7AOTf (right-hand-side). H-atoms and isopropyl group have been hidden.

Subsequently, we investigated the isomers 1,3,5,7BCl and 1,3,5,7BOTf, which have the axial and equatorial ligands swapped as compared to structure AL (L = Cl− or OTf−), Scheme 1, i.e. the thiophenolate is put in the axial position of the iron(III)-superoxo and the anionic ligand (Cl− or OTf−) is in the equatorial position. Optimized geometries of the lowest lying singlet, triplet, quintet and septet spin state structures are depicted in Fig 5. Similarly to the results described above on 1,3,5,7ACl, also for BCl the septet spin state is the ground state followed by the quintet and triplet spin states, whereas the closed-shell singlet spin state is well higher in energy. Relative energies of the four spin states is: 7BCl (0.0 kcal mol−1), 5BCl (19.6 kcal mol−1) 3BCl (27.8 kcal mol−1) and 1BCl (46.6 kcal mol−1). It appears, therefore, that the septet spin state is considerably stabilized over the other three spin states, although the relative energies between 1,3,5A and 1,3,5B are not dramatically different.

Fig 5.

Optimized geometries of 1,3,5,7BCl (left-hand-side) and 1,3,5,7BOTf (right-hand-side) with bond lengths in angstroms. Isopropyl groups have been hidden.

Geometrically, there are similarities as well as differences between the structures 1,3,5,7ACl, on the one hand, and 1,3,5,7BCl, on the other hand. First of all in 7BCl the oxygen group is not bound to the metal center, whereas in 7BOTf one ligand (SPh) has split off the metal center. Recent studies of ours36 showed that it is essential for sulphur oxygenation that dioxygen binds to the metal center prior to the reaction. Consequently, the septet structures are unlikely to be involved in the reaction mechanism for S-oxygenation. Despite the fact that the dioxygen bond length is virtually the same in all complexes, actually the metal-ligand distances show big differences. Thus, the metal-oxygen bond is significantly elongated from 1.912 Å in 3ACl to 2.027 Å in 3BCl and from 2.018 Å in 5ACl to 2.223 Å in 5BCl. At the same time elongation of the Fe–S bond occurs from 2.271 Å in 3ACl to 2.382 Å in 3BCl and from 2.364 Å in 5ACl to 2.972 Å in 5BCl. The latter structure, therefore, has a very weak thiophenolate bound and with a bond length of that magnitude cannot be considered as a covalent bond.

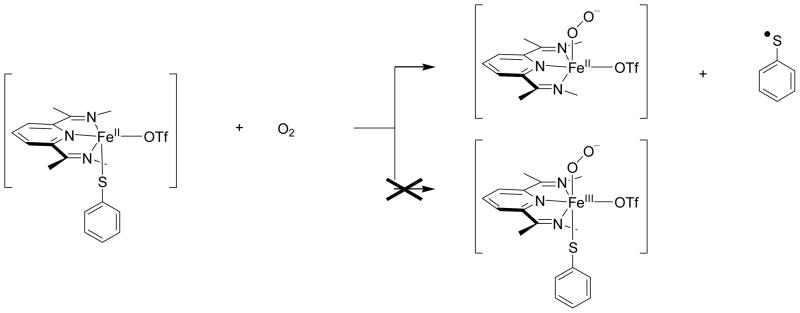

In the triflate bound isomers (3,5,7BOTf) this situation is even worse and the thiophenolate has dissociated completely from the metal and is optimized with a distance of around 6 Å. Hence, 3,5,7BOTf are pentacoordinate complexes. The reason for this is the considerable steric strain from the di-iso-propylphenyl groups that are attached to the BIP ligand. The group spin densities of these complexes characterize these structures as Fe(II)-superoxo with a nearby thiophenol radical, i.e. an electron transfer from thiophenol to the metal has taken place. This electron transfer fills the π*xz orbital with a second electron in both the triplet and quintet spin states. A single point calculation in a dielectric constant does not change the spin and charge distributions dramatically and keeps the system in a Fe(II)-superoxo-iPrBIP-(OTf) with a nearby SPh• radical. Therefore, upon approach of molecular oxygen to the [FeIII(SPh)(cis-OTf)(iPrBIP)]+ complex, during its binding to the vacant ligand position, the thiophenolate splits off as a SPh• radical, Scheme 2. Collision of two thiophenyl radicals then will form PhS–SPh complexes. Clearly, the binding affinity of molecular oxygen and the electron affinity of the complexes change from ligated triflate to chloride in the cis-position and as a consequence the complexes give differences in reactivity patterns.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of iron(II)-thiophenolate with dioxygen.

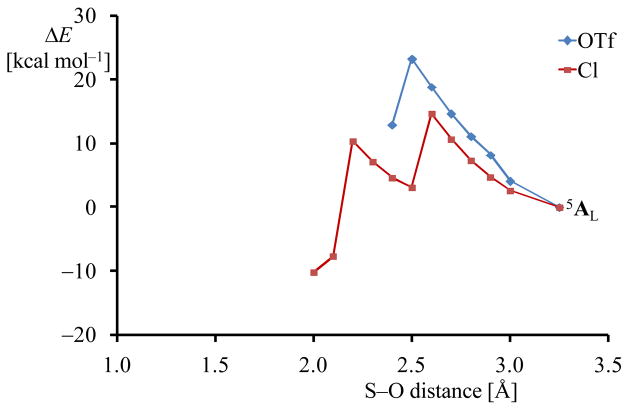

An oxygen atom transfer reaction from complexes A or B to give sulfoxides or double oxygen atom transfer leads to sulfinic acid products. Both processes starting from iron(III)-superoxo will be initiated by breaking the dioxygen bond. In previous work, we showed that the hydrogen atom abstraction reaction by iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin cation radical oxidants is proportional to the strength of the C–H bond that is broken as well as with the OH bond that is formed, i.e. the bond dissociation energy of the O–H bond or BDEOH.23b,26,37 By contrast, in sulfoxidation reactions by metal-oxo oxidants it was shown that the O–S bond formation step is linearly proportional to the O–H bond formation energy, and hence correlates with BDEOH as well.37d,38 In a similar vein we predict complex 5ACl to be more efficient in oxygen atom transfer reactions to substrates since the superoxo bond is weaker, hence it should be easier to break in the process. To test this we ran a geometry scan for the attack of the terminal oxygen atom of the superoxo group on the sulfur atom of SPh− for 5ACl and 5AOTf and the results are given in Fig 6. As follows, both reactions efficiently lead to a bicyclic ring structure, whereby an S–O bond is formed and the O–O bond is still intact, although weakened. This mechanism was also found for CDO enzymes using DFT and QM/MM methods.8 Indeed, as predicted from the optimized geometries of 5ACl and 5AOTf, the barrier height for oxygen attack on sulfur is smaller for 5ACl than for 5AOTf.

Fig 6.

Geometry scans for the attack of superoxo on the SPh− group in 5AL (L = Cl− or OTf−). Each point in the figure represents a full geometry optimization (UB3LYP/B1) with fixed S–O distance in Gaussian.

Energies are relative to 5AL (L = Cl− or OTf−).

How do our computations match the experiments reported on these particular systems? First of all, the crystal structure of Fe(II)-i-Pr-BIP with either chloride or triflate bound gave a structure of the B-type with chloride bound, but of A-type with triflate bound. These structures, of course, are pentacoordinated and no molecular oxygen is attached to the metal center. Nevertheless, we will compare the results obtained in this work with the pentacoordinate crystal structures from ref 11. The relative energy between structures 5ACl and 5BCl is calculated to be 1.2 kcal mol−1 in favour of structure A. Therefore both isomers could exist in equilibrium in solution. By contrast, for the triflate structure 5AOTf is well lower in energy than 5BOTf by 23 kcal mol−1 due to the dissociation of the thiophenol from the metal center in B. It appears therefore that the cavity within the iPrBIP ligand is too small to fit the triflate ligand. By contrast, small anions, such as chloride, fit into the cavity easily. As a consequence, the triflate bound structure resides in an orientation with the thiophenolate in the cis-position (equatorial), i.e. in a position adjacent to the superoxo group. Because of this positioning, the sulphur atom will be accessible for attack by dioxygen and efficient dioxygenation may occur. This result is indeed what Goldberg and co-workers observed with this complex. By contrast, the thiophenolate ligand is in the trans-position (axial) in the chloride bound structure, and it is located too far away from molecular oxygen to enable reactivity. However, these stable complexes may have a finite lifetime and during the course of that lifetime collisions of two 5ACl structures may occur that lead to disulfide product complexes.

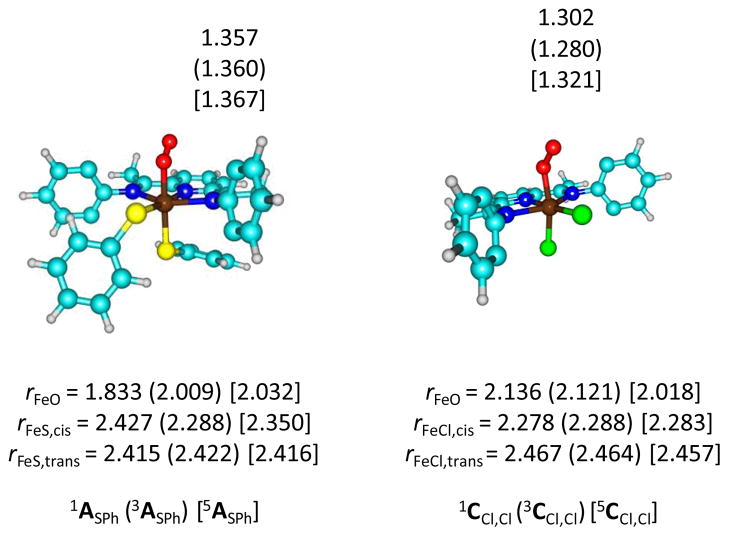

To further ascertain the effect of cis-triflate on binding of thiophenolate in the trans-position, we calculated two additional structures, namely one with thiophenolate in both cis and trans positions (ASPh) and one with chloride in both cis and trans positions (CCl,Cl), Fig 7. Both structures, in analogy with ACl, AOTf, BCl and BOTf discussed above have the quintet spin state well below the triplet and singlet spin states by more than 10 kcal mol−1. Optimized geometries are in line with the structures displayed in Fig 2 above with iron-cis-ligand distances of 2.350 and 2.283 Å for 5ASPh and 5CCl,Cl, respectively.

Fig 7.

Optimized geometries of 1,3,5ASPh (left-hand-side) and 1,3,5CCl,Cl (right-hand-side) with bond lengths in angstroms. Isopropyl groups have been hidden.

In the metal-trans-ligand distances are somewhat longer than the metal-cis-ligand ones, namely 2.416 and 2.457 Å for 5ASPh and 5CCl,Cl, respectively, which is as a result of orbital occupation. Nevertheless, thiophenolate binds in the axial ligand position, but only when either chloride or thiophenolate is in the cis-position. Bulky triflate ligands, therefore, in the cis-position prevent binding of thiophenolate in the axial position and a dissociative system is found for BOTf.

In summary, the key feature that determines dioxygenation of thiophenol by these nonheme iron complexes appears to be the availability of a cis-binding site on the metal adjacent to the dioxygen binding position. Stereochemical interactions of ligands as in the case of structure B prevent binding of thiophenolate in an appropriate position and consequently cannot bind it. However, these complexes can donate electrons rather than binding substrate that will then lead to formation of PhS–SPh products.

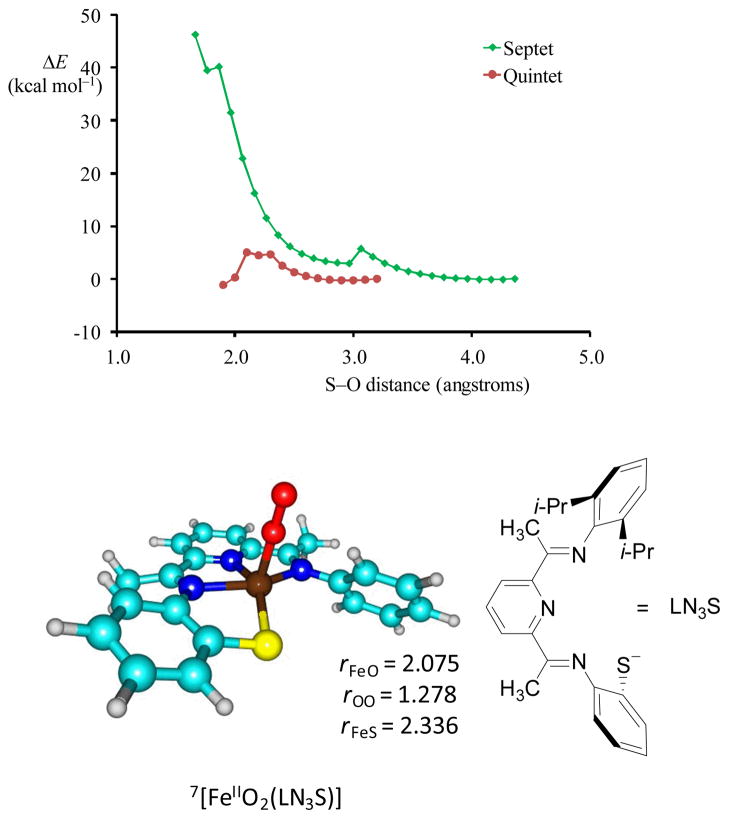

How does the work compare to other computational studies of CDO model complexes? Recent computational studies36 on a related CDO mimic with bis(imino)pyridyl ligand and pendant thiolate group (LN3S) revealed a sulphur dioxygenation mechanism similar to CDO enzymes on competing singlet, triplet and quintet spin state surfaces. In these studies the possible septet spin state was not considered. However, in light of recent experimental studies on CDO enzymes that seem to implicate a septet spin iron(III)-superoxo species,29 as well as the studies presented in this work, we decided to revisit our study and calculate the septet spin [FeIIO2(LN3S)] and its oxygen activation reaction.

As follows from Fig 8 the iron(III)-superoxo structure in the septet spin state is slightly lower in energy to that found for the quintet spin state; in the gas-phase ΔE+ZPE is 1.8 kcal mol−1 whereas in solvent it is 0.9 kcal mol−1. This implies that technically, the iron(III)-superoxo structure can exist in close lying septet and quintet spin state structures. To find out whether the septet spin state is reactive, we investigated the S–O bond formation step in the dioxygenation process of the LN3S ligand. In the quintet spin state a low barrier of 5.0 kcal mol−1 was found. A geometry scan starting from the iron(III)-superoxo complex in the septet spin state (top panel in Fig 8), however, shows a continuous climbing energy curve that does not reach a local minimum for an intermediate in the dioxygenation process. The maximum point of the scan is well higher in energy than reactants, i.e. by more than 40 kcal mol−1. Clearly, the septet spin state, even if it exists, is an unreactive state that will not be able to participate in the reaction mechanism. Consequently, a spin crossing from septet back to quintet will be required for the dioxygenation process to proceed.

Fig 8.

Septet and quintet S–O bond formation scan and optimized geometry of 7[FeIIIO2(LN3S)] with distances in angstroms.

Conclusions

Density functional theory calculations are presented on biomimetic model complexes of cysteine dioxygenase. Our studies show that it is vital to have a thiolate substrate bound in the cis-position of the dioxygen moiety. Preventing substrate binding through stereochemical interactions of other ligands prevents substrate dioxygenation. However, the iron(III)-superoxo complex is a good electron acceptor and easily abstracts electrons from thiophenols so that they can react further to form PhS–SPh via a bimolecular reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Service for Computational Chemistry Software (NSCCS) for cpu time and MGQ thanks the BBSRC for a studentship. The University of Manchester is acknowledged for a travel grant. DK holds a Ramanujan Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi (India), and acknowledges its financial support (Research Grants SR/S2/RJN-11/2008 and SR/S1/PC-58/2009). The NIH (GM62309 to D.P.G.) is gratefully acknowledged for partial support of this work.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Footnotes should appear here. These might include comments relevant to but not central to the matter under discussion, limited experimental and spectral data, and crystallographic data.

Contributor Information

Devesh Kumar, Email: dkclcre@yahoo.com.

David P. Goldberg, Email: dpg@jhu.edu.

Sam P. de Visser, Email: sam.devisser@manchester.ac.uk.

Notes and references

- 1.a) Solomon EI, Brunold TC, Davis MI, Kemsley JN, Lee SK, Lehnert N, Neese F, Skulan AJ, Yang YS, Zhou J. Chem Rev. 2000;100:235. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bugg TDH. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:550. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Chem Rev. 2004;104:939. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Bruijnincx PCA, van Koten G, Klein Gebbink RJM. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:2716. doi: 10.1039/b707179p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) de Visser SP, Kumar D, editors. Iron-containing enzymes: Versatile catalysts of hydroxylation reactions in nature. RSC Publishing; Cambridge (UK): 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Krebs C, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:484. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schofield CJ, Zhang Z. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;9:722. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bugg TDH. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7075. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Choroba OW, Williams DH, Spencer JB. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5389. [Google Scholar]; b) Higgins LJ, Yan F, Liu P, Liu HW, Drennan CL. Nature. 2005;437:838. doi: 10.1038/nature03924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bodner MJ, Phelan RM, Freeman MF, Li R, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12. doi: 10.1021/ja907320n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Trewick SC, Henshaw TF, Hausinger RP, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B. Nature. 2002;419:174. doi: 10.1038/nature00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Falnes PØ, Johansen RF, Seeberg E. Nature. 2002;419:178. doi: 10.1038/nature01048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mishina Y, Duguid EM, He C. Chem Rev. 2006;106:215. doi: 10.1021/cr0404702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Stipanuk MH. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Straganz GD, Nidetzky B. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1536. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Joseph CA, Maroney MJ. Chem Commun. 2007:3338. doi: 10.1039/b702158e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye S, Wu X, Wei L, Tang D, Sun P, Bartlam M, Rao Z. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) McCoy JG, Bailey LJ, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Aceti DJ, Fox BG, Phillips GN., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509262103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chai SC, Bruyere JR, Maroney MJ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Simmons CR, Liu Q, Huang Q, Hao Q, Begley TP, Karplus PA, Stipanuk MH. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dominy JE, Jr, Simmons CR, Karplus PA, Gehring AM, Stipanuk MH. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5561. doi: 10.1128/JB.00291-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Pierce BD, Gardner JD, Bailey LJ, Brunold TC, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8569. doi: 10.1021/bi700662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Dominy JE, Jr, Hwang J, Guo S, Hirschberger LL, Zhang S, Stipanuk MH. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800044200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Kleffmann T, Jongkees SAK, Fairweather G, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:913. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Gardner JD, Pierce BS, Fox BG, Brunold TC. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6033. doi: 10.1021/bi100189h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Tchesnokov EP, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. Biochemistry. 2012;51:257. doi: 10.1021/bi201597w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Aluri S, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14846. doi: 10.1021/ja0758178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Visser SP, Straganz GD. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:1835. doi: 10.1021/jp809700f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kumar D, Thiel W, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3869. doi: 10.1021/ja107514f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Kryatov SV, Rybak-Akimova EV, Schindler S. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2175. doi: 10.1021/cr030709z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Abu-Omar MM, Loaiza A, Hontzeas N. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2227. doi: 10.1021/cr040653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nam W. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:522. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Jiang Y, Widger LR, Kasper GD, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12214. doi: 10.1021/ja105591q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McQuilken AC, Jiang Y, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134 doi: 10.1021/ja302112y. ASAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badiei YM, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1274. doi: 10.1021/ja109923a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sallmann M, Siewert I, Fohlmeister L, Limberg C, Knispel C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2234. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Dawson JH, Holm RH, Trudell JR, Barth G, Linder RE, Bunnenberg E, Djerassi C, Tang SC. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:3707. doi: 10.1021/ja00428a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Poulos TL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1996;1:356. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Green MT, Dawson JH, Gray HB. Science. 2004;304:1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1096897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Woggon WD. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:127. doi: 10.1021/ar0400793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar D, de Visser SP, Sharma PK, Derat E, Shaik S. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:181. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogliaro F, de Visser SP, Shaik S. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;91:554. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Gross Z, Nimri S. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:1731. [Google Scholar]; b) Gross Z. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1996;1:368. [Google Scholar]; c) Czarnecki K, Nimri S, Gross Z, Proniewicz LM, Kincaid JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2929. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Nam W, Ryu YO, Song SJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:654. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Song WJ, Ryu YO, Song R, Nam W. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:294. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Sastri CV, Lee J, Oh K, Lee YJ, Lee JJ, Jackson TA, Ray K, Hirao H, Shin W, Halfen JA, Kim J, Que L, Jr, Shaik S, Nam W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709471104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Anastasi AE, Comba P, McGrady J, Lienke A, Rohwer H. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:6420. doi: 10.1021/ic700429x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jensen MP, Mairata A, Payeras I, Fiedler AT, Costas M, Kaizer J, Stubna A, Münck E, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2007;46:2398. doi: 10.1021/ic0607787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jackson TA, Rohde JU, Seo MS, Sastri CV, DeHont R, Stubna A, Ohta T, Kitagawa T, Münck E, Nam W, Que L., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12394. doi: 10.1021/ja8022576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zhou Y, Shan X, Mas-Ballesté R, Bukowski MR, Stubna A, Chakrabarti M, Slominski L, Halfen JA, Münck E, Que L., Jr Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1896. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Hirao H, Que L, Jr, Nam W, Shaik S. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:1740. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Hong S, Lee JM, Nam W. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:354. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Cho KB, Moreau Y, Kumar D, Rock DA, Jones JP, Shaik S. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:4103. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Namuswe F, Kasper GD, Sarjeant AAN, Hayashi T, Krest CM, Green MT, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14189. doi: 10.1021/ja8031828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stasser J, Namuswe F, Kasper GD, Jiang Y, Krest CM, Green MT, Penner-Hahn J, Goldberg DP. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:9178. doi: 10.1021/ic100670k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Namuswe F, Hayashi T, Jiang Y, Kasper GD, Sarjeant AAN, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:157. doi: 10.1021/ja904818z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Prokop KA, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5091. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Prokop KA, Neu HM, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15874. doi: 10.1021/ja2066237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai N, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al–Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, revision C.02. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) de Visser SP. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:8168. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Visser SP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1790. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9813. doi: 10.1021/ja061581g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kumar D, Karamzadeh B, Sastry GN, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7656. doi: 10.1021/ja9106176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]; b) Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:270. [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1087. doi: 10.1021/ja908340j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwabe T, Grimme S. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:3397. doi: 10.1039/b704725h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Kumar D, de Visser SP, Shaik S. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:2825. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Visser SP, Oh K, Han AR, Nam W. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:4632. doi: 10.1021/ic700462h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Vardhaman AK, Sastri CV, Kumar D, de Visser SP. Chem Commun. 2011;47:11044. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13775a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford JA, Li W, Pierce BS. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10241. doi: 10.1021/bi2011724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbughuni MM, Chakrabarti M, Hayden JA, Bominaar EL, Hendrich MP, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Rydberg P, Sigfridsson E, Ryde U. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:203. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0515-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jensen KP, Roos BO, Ryde U. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:45. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nakashima H, Hasegawa JY, Nakatsuji H. J Comp Chem. 2006;27:1363. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Annaraj J, Cho J, Lee YM, Kim SY, Latifi R, de Visser SP, Nam W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4150. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) de Visser SP. Coord Chem Rev. 2009;253:754. [Google Scholar]; f) Lai W, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5444. doi: 10.1021/ja111376n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Latifi R, Tahsini T, Kumar D, Sastry GN, Nam W, de Visser SP. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10674. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13993b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Cho KB, Chen H, Janardanan D, de Visser SP, Shaik S, Nam W. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2189. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17610f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.a) de Visser SP. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:168. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Visser SP, Tahsini L, Nam W. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:5577. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.a) Emerson JP, Farquhar ER, Que L., Jr Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) van der Donk WA, Crebs K, Bollinger JM., Jr Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:1. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lee YM, Hong S, Morimoto Y, Shin W, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10668. doi: 10.1021/ja103903c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mukherjee A, Cranswick MA, Chakrabarti M, Paine TK, Fujisawa K, Münck E, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2010;49:3618. doi: 10.1021/ic901891n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.a) Bassan A, Borowski T, Siegbahn PEM. Dalton Trans. 2004:3153. doi: 10.1039/B408340G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shaik S, Kumar D, de Visser SP, Altun A, Thiel W. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2279. doi: 10.1021/cr030722j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Georgiev V, Borowski T, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:929. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Haahr LT, Jensen KP, Boesen J, Christensen HEM. J Inorg Biochem. 2010;104:136. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.a) de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15809. doi: 10.1021/ja065365j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bernasconi L, Baerends EJ. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2008:1672. doi: 10.1021/ic800998n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar D, Sastry GN, Goldberg DP, de Visser SP. J Phys Chem A. 2012;116:582. doi: 10.1021/jp208230g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.a) de Visser SP, Kumar D, Cohen S, Shacham R, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8362. doi: 10.1021/ja048528h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shaik S, Kumar D, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10128. doi: 10.1021/ja8019615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Latifi R, Bagherzadeh M, de Visser SP. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:6651. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kumar D, Sastry GN, de Visser SP. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:6196. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kumar D, Sastry GN, de Visser SP. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:718. doi: 10.1021/jp2113522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Latifi R, Valentine JS, Nam W, de Visser SP. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3491. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30365e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar D, de Visser SP, Sharma PK, Hirao H, Shaik S. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8148. doi: 10.1021/bi050348c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.