Abstract

BACKGROUND

The prognosis for hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies is dismal. Surgery remains the primary curative option but unresectable disease is often discovered during operative exploration. Positron emission tomography (PET) provides unique biological information different from current imaging modalities. The purpose of this paper is to review the literature on the use of PET in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies

DATA SOURCES

We performed an extensive search on PubMed, using PET and hepatocellular, pancreatic, gallbladder, and cholangiocarcinoma as keywords, excluding articles not written in English or on non-human subjects, case reports, and series with <5 patients.

CONCLUSION

Although PET has shown usefulness in the diagnosis of certain cancers, current literature cautions against the use of PET for determining malignant potential of primary liver and pancreatic lesions. Literature on PET more strongly supports clinical roles for restaging of hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies, and for identifying metastatic disease.

SUMMARY

The role of PET in detecting hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies has not yet been clearly defined. This article surveys the literature on the use of PET in identifying hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

The prognosis for hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies is dismal with 5-year survival ranging from 5–20%1. Accurate detection, diagnosis, and staging may lead to more appropriate treatments and improved clinical outcomes. Since surgical resection is the primary curative option for most hepatobiliary/pancreatic cancers, earlier and more accurate detection may increase the likelihood of timely intervention. Unfortunately, despite a variety of clinically available imaging techniques, unresectable disease often remains undiscovered until operative exploration.

Structural analysis forms the basis of conventional imaging such as CT and MRI, capitalizing on anatomical changes to detect disease. In contrast, positron emission tomography (PET) is based on identification of molecular biologic changes. Because tumors are metabolically distinct from normal tissue, their detectability on PET may be independent of their structural changes, although for anatomical localization, PET is often paired with computed tomography (CT) as a hybrid anatomical and metabolic imaging technique. Because PET tracers have little if any pharmacologic side effects, PET can safely provide biologic information about hepatobiliary and pancreatic tumors without the complications associated with other diagnostic interventions such as imaging with hyperosmolar contrast agents, fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP)2. The goal of this article is to summarize the clinical indications that have been explored regarding the use of PET in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies and to identify the specific clinical instances where potential benefits may be realized.

MECHANISM OF FLUORINE-18-FLUORODEOXYGLUCOSE UPTAKE

PET involves the administration of a positron-emitting radiopharmaceutical tracer whose metabolic fate can be imaged using a tomographic array of scintillation detectors. The most widely used, and currently the only oncologic tracer approved by the US FDA, is fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), a glucose analog that is metabolized in a manner which mimics glucose utilization in the body. Similar to glucose, FDG is transported into cells through specific glucose transporters found along the cell membrane. After pharmacologic uptake, FDG is metabolized and phosphorylated by hexokinase as part of the glycolytic pathway. However, since phosphorylated FDG cannot participate further in glycolysis, it accumulates intracellularly forming the basis of tumor detection via increased FDG uptake. Many tumor types are known to paradoxically demonstrate increased glyocolytic metabolism even under aerobic conditions (known as the Warburg effect), which affords their detection by FDG PET3–5.

However, variability in the uptake of FDG among different tumors can lead to significant differences in detection rates. For example, the sensitivity of PET for primary pancreatic cancer ranges from 70–100%, while the sensitivity for hepatocellular cancer using PET is lower at 50–70%6–9. Furthermore, cells of normal tissues such as the brain and liver have relatively high physiologic FDG uptake, which may hamper visual discrimination of tumors in these organs. Because FDG is a glucose analog, its uptake in tumors and normal tissues may also be influenced by dietary state, as well as blood glucose. As a result, patients are required to fast prior to PET scan and diabetic patients are routinely required to have near-normal glucose levels to produce a reliable PET result.

HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer death worldwide with an estimated 652,000 deaths in 200810. In the US, an estimated 22,620 people were diagnosed with liver cancer and 18,160 people died from this in 2009. Liver cancer is one of two cancers in the US that is increasing both in incidence and death rate during 2002–20061. Strategies for HCC rely heavily on screening patients with viral hepatitis or cirrhosis of any etiology, using ultrasound followed by CT, MRI and/or liver biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Surgical resection and liver transplant remain the best options for cure in HCC. However, surgery is frequently not possible due to tumor size, multifocal disease, extrahepatic involvement or insufficient hepatic reserve. Although PET has been widely studied in metastatic diseases to the liver, the role of PET in the diagnosis of primary hepatic neoplasms is not as well delineated11, 12. Furthermore, the few retrospective studies available generally do not support PET for use as a first-line imaging modality for HCC6–9, although potential value may still exist in well-defined populations or very specific clinical situations.

Potential Uses of PET in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

One promising potential use of PET for HCC is in identifying extrahepatic lesions which may be indeterminate or overlooked on conventional CT. In a study of 91 patients with HCC by Wudel et al, the addition of PET led to the discovery of metastatic lesions of clinical significance in 28% of the patients9. The value of PET in detecting secondary liver tumors has also been shown in studies comparing PET to ultrasound, CT, and MRI (Table 1). Therefore, in patients at increased metastatic risk, PET can provide staging information that may alter clinical management.

Table 1.

Publications on Hepatocellular Carcinoma and PET

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | N | Results | Conclusion |

| Khan | 2000 | 20 | Sensitivity of 55% compared to CT (90%) in identifying primary HCC | Poor sensitivity for detection of primary HCC tumors |

| Bohm | 2004 | 50 | Sensitivity of 52% compared to US, CT, and MRI (61%, 81%, and 89%) in identifying primary HCC | Poor sensitivity for detection of primary HCC tumors |

| Metastasis | ||||

| Khan | 2000 | 20 | Identified three patients with metastatic lesions not seen on CT | Possible use as adjunct to CT for staging of HCC |

| Wudel | 2003 | 91 | Identified distant metastasis in 8 out of 49 patients with untreated HCC or HCC recurrence after therapy | Useful as a tool for tumor staging |

| Bohm | 2004 | 50 | Sensitivity of 63% compared to US, CT, and MRI (29%, 47%, and 40%) in identifying distant metastases, resulting in change in management of 18% of patients | Better than US, CT, and MRI in detecting extrahepatic disease |

| Recurrence after therapy | ||||

| Donckier | 2003 | 17 | Identified residual tumor 1 week after RFA in 4 patients; continued positivity on PET at 1- and 3-month follow-up not seen on CT | Accurately monitors efficacy of RFA for liver lesions |

| Anderson | 2003 | 13 | Detected 8 patients with recurrent tumor at ablation site and 3 new metastases after RFA compared to MRI and CT | Superior to MRI and CT for surveillance of hepatic tumors after ablation |

| Paudyal | 2007 | 24 | Detected recurrence 4–6 months after RFA in 2 patients whereas none was detected on CT; detected recurrence between 7–9 months in 6 patients vs 4 patients on CT | Potential tool for diagnosis of recurrence after RFA |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Khan | 2000 | 20 | Well-differentiated tumor had higher PET activity (scale 1–4) compared to moderately and poorly-differentiated HCC tumors | May be helpful in assessing tumor differentiation |

| Wudel | 2003 | 91 | High grade HCC (moderately to poorly differentiated) tumors had statistically significant greater FDG positivity compared to lower grade HCC | May be helpful in assessing tumor differentiation |

| Seo | 2007 | 70 | Poorly differentiated HCC had significantly higher SUV which correlated with lower overall survival compared to well and moderately differentiated HCC | FDG uptake on PET may be a predictor of outcome in HCC patients |

| Pandyal | 2007 | 24 | Well-differentiated HCC had lower SUV values compared to moderately and poorly differentiated HCC; high SUV values were seen in patients with earlier recurrence | May be helpful in assessing tumor differentiation and determining prognosis |

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PET: Positron emission tomography; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; RFA: Radio frequency ablation; FDG: Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose; SUV: Standardized uptake value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Though complete surgical resection is the best option for cure, other treatments are available for inoperable disease. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is used in both primary and metastatic liver tumor but the completeness of tumor ablation after RFA is difficult to determine both intra-operatively and at follow-up. Although PET has shown limited utility in detecting primary HCC lesions, it may be useful for tumor surveillance after RFA14. In a study of patients post-RFA, Anderson et al15 detected the sites of recurrent tumor or new metastases using PET in 11 patients. Paudyal et al16 followed 33 HCC lesions in 24 patients using PET for two years and determined that PET was not only able to determine recurrence earlier (92%) than CT, but also able to identify recurrence not seen on CT as early as 4–6 months after treatment. Thus, potential uses of PET in staging, restaging, and surveillance in HCC may be deserving of clinical evaluation in larger studies.

A number of studies have also evaluated FDG uptake on PET as a non-invasive means of grading tumor differentiation. Paudyal et al18 found a significant difference in standardized uptake value (SUV) between well and moderately differentiated HCC and between well and poorly differentiated HCC. In a similar study looking at SUV, Seo et al19 found a correlation between SUV, SUV ratio and survival. Besides a statistically higher SUV and SUV ratio between poorly differentiated and well/moderately differentiated HCC, disease-free survival was much lower among the poorly differentiated or higher SUV and SUV ratio lesions. Khan et al8 also showed a significant difference in PET activity between well, moderately, and poorly differentiated HCC. Since FDG uptake is a marker of glyocolytic activity, these findings imply that tumors exhibiting higher rates of glucose metabolism may be associated with more aggressive tumors and is indicative of an unfavorable prognosis.

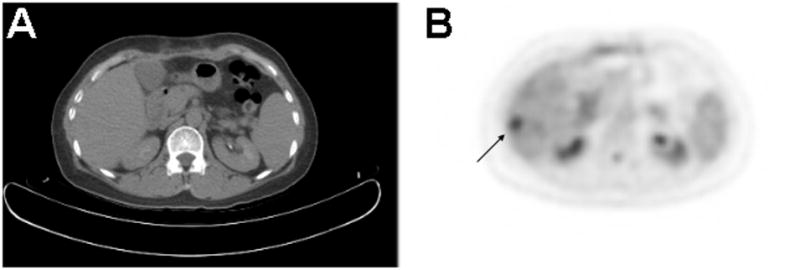

Limitations of PET in HCC

Ironically, the same reason that PET can discern tumor differentiation may also explain its poor overall rate of detecting primary HCC. Hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphatase is highly expressed in normal hepatocytes but in tumors may vary greatly depending on the degree of tumor differentiation. Consequently, tumors may not be readily distinguishable in the liver on the basis of glucose metabolism due to variable FDG uptake relative to normal liver tissue (Figure 1). This may account for the poor detection rates reported in a few studies8,13. Bohm et al13 compared PET with ultrasound, CT, and MRI, and found PET to be only slightly better than CT and US and inferior to MRI. Other studies have reported similar results in detecting HCC using PET (Table 1). There currently is little data on the variability of FDG uptake by normal and diseased liver tissue. Since 75% of HCC arise in the setting of chronic liver disease, it is important to understand how cirrhosis and other conditions may affect hepatocyte FDG metabolism, and consequently the diagnostic performance of FDG PET.

Figure 1.

PET/CT in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. A.) There is no evidence of liver tumor on the CT performed in tandem with PET, given that PET/CT is usually obtained without the administration of intravenous contrast. B.) On the FDG PET image, a 1.5 cm diameter hypermetabolic focus is seen in hepatic segment 6, corresponding to the primary malignancy. Diminished physiologic uptake of FDG resulting from chronic liver disease may have enhanced the conspicuity of HCC in this case. In general, the sensitivity of FDG PET for detecting HCC is sub-optimal due to physiologic FDG uptake by the normal liver

As a diagnostic imaging technique, another limitation of PET is coarser spatial resolution compared to CT and MRI. This restricts the role of PET for determining liver tumor resectability since PET is often performed in conjunction with a “low-dose” CT scan without intravenous contrast, rendering this suboptimal for assessing structural details or vascular invasion. Thus, PET should be used in complement to the other structural imaging techniques in patients who are potential surgical candidates.

While there is insufficient data to support routine detection of primary HCC with FDG PET, there is some data supporting a potential role for detecting extrahepatic disease and tumor recurrences after treatment. Further investigations are necessary to substantiate a favorable cost to benefit ratio for these potential indications.

CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is the second most common hepatobiliary malignancy after HCC. Prognosis is generally poor due to difficulties in early diagnosis and late clinical presentation. The two types of CCA are distinguished based on location within the biliary tree. Intrahepatic CCA often presents as larger, more advanced disease with pain or a palpable mass. Perihilar, or extrahepatic CCA is more common and presents with obstructive jaundice. CT and MRI are adequate for demonstrating biliary obstruction while MRCP may provide more precise detail at the site of obstruction. Surgical resection is the optimal curative treatment but many patients are diagnosed in advanced stages and are not surgical candidates. An ideal imaging modality is not yet available to accurately diagnose, stage, and monitor therapy in patients with CCA.

Potential Uses of PET in Cholangiocarcinoma

Similar to HCC, PET may be useful in detecting distant metastatic CCA. Several retrospective studies have shown PET to be superior to CT at detecting distant metastases (Table 2). In a prospective study by Kim et al22, PET proved significantly more accurate in identifying distant metastasis compared to CT (58% vs 0%). Other studies have confirmed the utility of PET for detecting metastases not detected by other imaging23, ultimately influencing clinical management in up to 25% of patients24.

Table 2.

Publications on Cholangiocarcinoma and PET

| Cholangiocarcinoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | N | Results | Conclusion |

| Kluge | 2001 | 26 | Sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 93% in identifying CCA | Suitable for detection of CCA |

| Anderson | 2004 | 36 | Overall sensitivity of 61% for detecting CCA; 85% for nodular-type and 18% for infiltrating-type CCA | PET may not be able to differentiate various histological types of CCA |

| Petrowsky | 2006 | 47 | Sensitivity for intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA were 93% and 55% compared to 78% and 58% for CT | PET superior to CT for intrahepatic CCA but not for extrahepatic CCA |

| Corvera | 2007 | 62 | Sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 75% for all CCA types; sensitivity differed between intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA (95% vs 69%) | High rate of detecting CCA but overall more sensitive for intrahepatic than extrahepatic CCA |

| Kim | 2008 | 123 | Sensitivity of 95% and 81% for intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA compared to CT (95%, 81%) and MRI (100%, 95%) | Comparable to CT but inferior to MRI in detecting CCA |

| Moon | 2008 | 54 | Sensitivity of 91% for intrahepatic CCA and 83% for perihilar CCA compared to CT (87% and 92%) | May be useful as a complementary tool to CT for detecting CCA |

| Metastasis | ||||

| Kluge | 2001 | 26 | Identified 7 out of 10 patients with distant metastases but only 2 out of 15 patients with known regional nodes | Suitable for detecting distant metastases but not regional lymph nodes |

| Petrowsky | 2006 | 47 | Detected 2 out of 17 regional metastases but 12 out of 12 distant metastases | PET not suitable for detection of regional lymph nodes but valuable for distant metastases |

| Corvera | 2007 | 62 | Overall sensitivity of 95% in detecting nodal and distant metastases, resulting in change of treatment in 25% of patients | Good for detecting both regional and distant metastases |

| Kim | 2008 | 123 | Distant metastasis detection rate of 58% compared to 0% for CT | Valuable for detecting distant metastases |

| Moon | 2008 | 54 | Detected 24 out of 24 metastatic foci in 19 patients in addition to 9 metastatic lesions not previously seen on CT | Good for detecting distant metastases |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Moon | 2008 | 54 | Showed significant difference in SUVmax and SUV ratio between benign and malignant lesions. Perihilar CCA had significantly lower values compared to intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA | Shows promise in differentiating benign from malignant disease |

CCA: Cholangiocarcinoma; PET: Positron emission tomography; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; RFA: Radio frequency ablation; FDG: Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose; SUV: Standardized uptake value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Limitations of PET in Cholangiocarcinoma

The sensitivity of FDG PET for detecting primary CCA has been estimated at 78%24. However, a few studies have shown differences in detection rates for intrahepatic and extrahepatic tumors. Petrowsky et al20 found PET/CT to be more sensitive (93% vs 55%) and specific (80% vs 33%) in detecting intrahepatic versus extrahepatic CCA. This discrepancy between intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA has also been noted by other studies22, 24. Another limitation is that the cancer type and tumor size may influence PET results for CCA. Kluge et al21 reported a sensitivity of 92% in detecting hilar CCAs but indicated that the rate of detection of extrahepatic tumors is dependent upon the shape of the tumor. Corvera et al24 further analyzed that intrahepatic CCA were larger in size and thus had a higher detection rate when compared to other types of CCA. The sensitivity of PET for nodular-type CCA was found to be significantly greater than for infiltrating-type CCA (85% vs 18%)25. It should be noted that these detection rates derived from retrospective data analysis may also reflect differences in clinical presentation between intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA.

GALLBLADDER CANCER

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the fifth most common cancer of the gastrointestinal tract with approximately 6,000 new cases each year1. The prognosis for GBC remains poor with 5-year survival rate of 15–20% as only 10% of cancers are localized to the gallbladder at discovery26. The diagnosis of GBC remains difficult due to similar clinical presentation to cholecystitis and biliary colic. Thus, despite the poor ability of ultrasound and CT to distinguish malignant from benign gallbladder disease, these studies are most commonly used for the detection of GBC. GBC is incidentally found in an estimated 1–3% of cholecystectomies. When GBC is suspected and detected before surgery, it is often because the cancer has already become regionally advanced or has metastasized.

Potential Uses of PET in Gallbladder Cancer

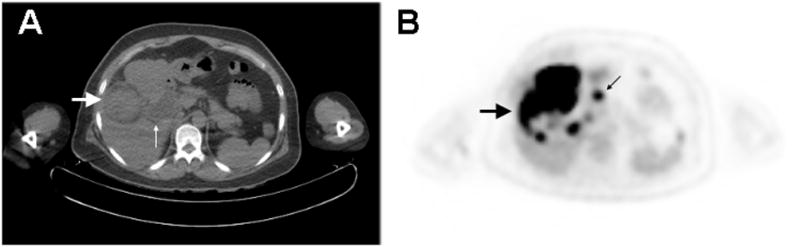

A few studies have suggested that PET is highly sensitive for detection of GBC (75–100%)20, 25, 27 (Table 3). A case report published by Lin et al28 utilized PET to confirm the diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder and identify metastatic disease (Figure 2). Other small studies have also supported the potential value of PET in detecting distant metastasis, although given the relatively low prevalence of GBC, there are still insufficient data to establish the overall accuracy of PET for whole-body staging. Nevertheless, PET detected distant metastases in all 7 patients with metastatic GBC in one study20, while another study detected metastases in 3/6 patients with known metastatic GBC25. In a third study, PET was shown to lead to the identification of metastases not seen on other imaging modalities, leading to a change in stage and treatment in 23% (7/31) of patients with GBC24. Butte et al29 also examined the use of PET/CT in 32 patients with GBC incidentally discovered after cholecystectomy and showed a significant difference in mean survival between patients with negative, locally-advanced, and metastatic findings on PET/CT (13.5 vs 6.2 vs 4.9 months, respectively). Thus these studies support the potential clinical and prognostic impact of PET based staging of GBC.

Table 3.

Publications on Gallbladder Cancer and PET

| Gallbladder cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | N | Conclusion | |

| Rodriguez-Fernandez | 2004 | 16 | Sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 82% in identifying GBC in patients with biliary colic | Accurate method of differentiating malignant from benign gallbladder disease |

| Petrowsky | 2006 | 14 | Identified 14 out of 14 with primary or recurrent GBC compared to 10 out of 14 using CT | Comparable in detecting GBC compared to CT |

| Corvera | 2007 | 31 | Sensitivity of 86% in identifying primary GBC Identified 24 out of 28 patients with primary GBC (Sens: 86%) | High detection rate for GBC |

| Metastasis | ||||

| Petrowsky | 2006 | 14 | Identified 7 out of 7 distant metastases in patients with GBC but only identified 2 out of 17 patients with biliary cancer and regional spread | Good for detecting distant but not regional lymph metastasis |

| Corvera | 2007 | 31 | Sensitivity of 87% in identifying metastatic GBC; 7 patients had metastases not previously seen, avoiding surgery in 4 patients | Valuable in detecting metastatic GBC not previously seen |

| Recurrence | ||||

| Anderson | 2004 | 14 | Sensitivity of 78% in detecting residual GBC after cholecystectomy | Good for detecting residual GBC |

GBC: Gallbladder cancer; PET: Positron emission tomography; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; RFA: Radio frequency ablation; FDG: Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose; SUV: Standardized uptake value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Figure 2.

PET/CT of Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Gallbladder. A.) CT image demonstrates a 4.4 cm diameter, intraluminal mass arising from the gallbladder encroaching upon the liver (large arrow). There is associated extra- and intra-hepatic biliary ductal dilatation (small arrow). B.) PET image shows the gallbladder mass to be hypermetabolic, with abnormal metabolism extending into the right hepatic lobe (large arrow). There are also additional discrete hypermetabolic nodules in the right hepatic lobe, as well as hypermetabolic mesenteric and omental lymphadenopathy (small arrow). These findings were consistent with the intraoperative findings of invasive gallbladder carcinoma involving the liver parenchyma as well as regional lymph node metastases.

Limitations of PET in Gallbladder Cancer

Unfortunately, several studies have also shown a poor sensitivity for detecting regional lymph node metastasis in GBC. Petrowsky et al20, in 61 patients with biliary and GBC, found only 12% of known regional metastases using PET. In another study, PET identified only 5 patients with locoregional spread out of 17 patients with unresectable, locally advanced disease confirmed on surgical exploration24.

Overall, evidence supporting the use of PET in GBC is still limited and larger studies are necessary to determine the potential of these techniques to influence patient outcomes.

PANCREATIC CANCER

The incidence of pancreatic cancer (PCA) has remained consistent over the past 30 years and is the fourth most common cause of cancer death. Pancreatic cancer was responsible for over 35,000 deaths per year in the United States in 2009 with overall 5-year survival of 5.5%1. Surgical resection remains the primary curative option but late presentation limits this option. Surgeons often underestimate the extent of disease and resectability thus improving current imaging modalities to better diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer may help avoid nontherapeutic exploratory surgery. PET scan has been shown to be a powerful staging tool for many cancers and has recently shown clinical promise in pancreatic cancer.

Potential Uses of PET in Pancreatic Cancer

The ability of PET to differentiate neoplasm from other mass-forming pancreatic lesions was shown to be comparable to CT in numerous studies, although some studies suggest that PET has moderately higher sensitivity of detecting pancreatic cancer (84–97%) when compared to CT (76–80%)30, 31, 36. Two recent prospective studies demonstrated comparable sensitivity (89%) when compared to CT32 and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)33. Schick et al33 showed that EUS had a slightly lower sensitivity than PET in detecting pancreatic malignancies with lesions that were 11–52 mm and of ductal carcinoma type. This contradicts several studies in which EUS had a greater than 90% detection rate for all pancreatic malignancies, especially those lesions smaller than 30mm34. Mertz et al35, in comparing EUS and PET in 35 patients with pancreatic cancer, found EUS more sensitive in detecting vascular invasion and PET to be more useful in detecting metastatic disease. Another study showed that though PET accurately detected only 71% of true pancreatic malignancies in a cohort of 31 patients, 7 out of 8 patients had negative findings on CT37. Though the role of PET in identifying pancreatic malignancies is yet undefined, the value of PET in pancreatic cancer may be in its ability to provide information that is supplementary to other imaging modalities.

One possible use for PET for pancreatic cancer is in differentiating benign and malignant disease in cystic lesions. Sperti et al38 studied 56 patients with suspected cystic lesions and found 17 patients with malignant tumors, of which 16 were correctly identified by PET compared to falsely identifying 5 benign lesions using CT and/or CA 19-9. Follow-up studies further defined the use of PET in cystic neoplasms identifying benign disease with a sensitivity of 97% in 71 patients with suspected intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms (IPMN)39. Increased uptake on PET was present in 4 of 5 carcinoma in situ (80%) and in 20 of 21 invasive cancers (95%), but was absent in 13 of 13 adenomas and 7 of 8 borderline IPMNs.

Though PET may only have a complementary role in diagnosing primary pancreatic lesions, PET may be valuable for staging and surveillance of pancreatic cancer. Heinrich et al32 showed that PET was able to detect metastasis in 13 of 16 patients with known metastases compared to CT which only detected 9 patients. Bang et al31 showed that more than one-fourth of patients with pancreatic cancer had a change in disease stage after PET identified 17 distant metastases not previously seen on CT. These studies show that PET may detect unsuspected metastases and thus prevent unnecessary surgical exploration.

Pancreatic cancer has a high recurrence and few studies have identified the optimal tool for detecting pancreatic tumor recurrence. A study comparing pre- and post-treatment scans showed PET to be more accurate in determining tumor response31. In a small study of 10 patients, PET demonstrated changes in the tumor after treatment not seen on CT or identified through tumor markers40. In a retrospective study by Sperti et al41 following pancreatic cancer patients after resection, PET was more sensitive in identifying recurrence compared to CT (Table 4). These studies suggest indicate that PET has a role in monitoringas a tool for follow-up after treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Table 4.

Publications on Pancreatic Cancer and PET

| Pancreatic cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | N | Results | Conclusion |

| Sendler | 2000 | 42 | Sensitivity of 71% compared to CT and US (74% and 56%) but identified 7 out of 8 false negative lesions on CT | Comparable to CT for detecting pancreatic cancer |

| Lemke | 2004 | 104 | Combined PET/CT sensitivity of 89% compared to CT alone (77%) and PET alone (84%). Sensitivity of 68% compared to CT (48%) in detecting infiltration of adjacent tissue | PET/CT comparable to CT or PET alone in detecting cancer but showed superiority in identifying infiltration |

| Heinrich | 2005 | 59 | Sensitivity of 89% compared to CT (93%) in detecting PCA | Comparable sensitivity to CT in diagnosing pancreatic cancer |

| Bang | 2006 | 102 | Sensitivity of 97% compared to CT (80%) in identifying PCA | Superior to CT in diagnosing pancreatic cancer |

| Schick | 2008 | 27 | Sensitivity of 89% compared to EUS (81%) and ERCP (87%) in identifying PCA | Comparable sensitivity in detecting pancreatic lesions with EUS and ERCP |

| Kauhanen | 2009 | 38 | Sensitivity and specificity of 85% and 94% compared to CT (85%, 67%) and MRI (85%, 72%) in identifying PCA. Sensitivity of 85% in determining benign from malignant biliary strictures | Comparable to CT and MRI in detecting pancreatic lesions and better in determining malignant biliary strictures |

| Metastasis | ||||

| Lemke | 2004 | 104 | PET/CT sensitivity of 32% compared to CT and PET alone (25%). Identified 5 additional metastases not previously seen | Good for detecting unidentified metastatic lesions |

| Heinrich | 2005 | 59 | Identified 13 out of 16 patients with metastases of which 5 were not seen on CT, while CT only identified 9 patients; PET only identified 3 out of 14 proven regional lymph node metastases | Better than CT in identifying distant metastases but poor in identifying regional disease |

| Bang | 2006 | 102 | Identified 17 new distant metastases in 72 cases of resectable disease, and changed pre-operative stage in 27% of patients | Better at detecting metastatic disease compared to CT |

| Strobel | 2008 | 50 | Enhanced PET/CT sensitivity of 96% compared PET alone and unenhanced PET/CT in determining resectability | Combined PET/CT is a feasible tool for identifying distant metastases, vascular infiltration, and local invasion |

| Kauhanen | 2009 | 38 | Sensitivity of 88% compared to CT and MRI in identifying metastases, affecting treatment in 26% of patients | Useful in detecting metastatic disease not identified on other imaging modalities |

| Recurrence/Response to treatment | ||||

| Bang | 2006 | 102 | Identified chemoradiation response in 5 out of 15 patients on pre- and post-treatment PET compared to none on CT | Better than CT in identifying tumor response to treatment |

| Sperti | 2010 | 72 | Identified 61 out of 63 patients with tumor relapse while CT identified only 35 patients | Better than CT in identifying tumor recurrence after pancreatic resection |

| Identifying cystic neoplasms | ||||

| Sperti | 2001 | 56 | Sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 97% compared to CT and CA19-9 (65% and 87%) in identifying malignant cystic neoplasms | Better than CT/CA 19-9 for identifying malignant cystic neoplasms |

| Sperti | 2007 | 71 | Sensitivity of 92% compared to CT and MRI (58% and 82%) in detecting IPMN Sensitivity of 92% compared to 58% and 82% for CT and MRI in detecting IPMN | Better than CT and MRI for detecting IPMN |

PCA: Pancreatic cancer; IPMN: intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms; PET: Positron emission tomography; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; RFA: Radio frequency ablation; FDG: Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose; SUV: Standardized uptake value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity

Limitations of PET in Pancreatic Cancer

The main limitation of PET may be the lack of anatomical detail to determine surgical resectability, specifically vascular infiltration and invasion of surrounding organs. Another limitation may be in differentiating benign inflammatory processes from malignancies (Figure 3). Strobel et al42, in considering pancreatic cancer resectability, determined that PET was able to detect metastases to the liver, lung, and bone but failed to detect arterial infiltration in all 5 patients with known tumor infiltration of the celiac trunk or superior mesenteric artery. Sendler et al37 showed that PET falsely identified 4 of 7 patients with chronic pancreatitis to have malignant disease. The potential for false positive PET findings resulting from non-malignant pancreatic diseases should also be a topic for further research.

Figure 3.

Coronal FDG PET Image of a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Although the malignant tumor involving the body of the pancreas (black arrow) was confirmed by histopathology, the fainter areas of increased activity in the pancreas adjacent to this tumor can represent either tumor infiltration or pancreatitis, since inflammation of the pancreas may also lead to increased FDG uptake in the pancreas.

CONCLUSION

The role of PET in detecting hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies has not yet been established. The current literature indicates that PET is not adequate in making the initial diagnosis of many primary hepatobiliary and pancreatic tumors. Though PET has shown utility in the diagnosis of certain cancers, variability in primary tumor detection across different organs cautions against the use of PET for assessing primary hepatobiliary and pancreatic lesions. More promising results have been obtained supporting the potential utility of FDG PET for whole-body staging, tumor grading, and surveillance in hepatobiliary malignancies. The literature on FDG PET in pancreatic tumors is maturing and potential clinical roles for FDG PET may still be established, particularly in situations where the revealing otherwise occult disease may alter the clinical management. Although no studies have primarily addressed cost-effectiveness, the ability of PET in pancreatic cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma to identify metastatic disease has reduced unnecessary surgeries, supporting future studies to determine whether this can result in an overall improvement in the cost-benefit equation of surgery in patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic tumors with high-risk clinical characteristics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER statistics. at www.cancer.gov/statistics.

- 2.Testoni PA, Mariani A, Giussani A, et al. Risk Factors for Post-ERCP Pancreatitis in High- and Low-Volume Centers and Among Expert and Non-Expert Operators: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1753–61. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higashi T, Tamaki N, Honda T, et al. Expression of glucose transporters in human pancreatic tumors compared with increased FDG accumulation in PET study. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1337–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okazumi S, Isono K, Enomoto K, et al. Evaluation of liver tumors using fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET: characterization of tumor and assessment of effect of treatment. J Nucl Med. 1992;33(3):333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paudyal B, Oriuchi N, Paudyal P, Higuchi T, Nakajima T, Endo K. Expression of glucose transporters and hexokinase II in cholangiocellular carcinoma compared using [18F]-2-fluro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:260–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delbeke D, Martin WH, Sandler MP, Chapman WC, Wright JK, Jr, Pinson CW. Evaluation of benign vs malignant hepatic lesions with positron emission tomography. Arch Surg. 1998;133:510, 5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.5.510. discussion 515–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trojan J, Schroeder O, Raedle J, et al. Fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography for imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3314–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan MA, Combs CS, Brunt EM, et al. Positron emission tomography scanning in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32(5):792–797. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wudel LJ, Jr, Delbeke D, Morris D, et al. The role of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Surg. 2003;69(2):117–124. discussion 124–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. at www.who.int.

- 11.Wiering B, Krabbe PF, Dekker HM, Oyen WJ, Ruers TJ. The role of FDG-PET in the selection of patients with colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:771–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubezky N, Metser U, Geva R, et al. The role and limitations of 18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan and computerized tomography (CT) in restaging patients with hepatic colorectal metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy: comparison with operative and pathological findings. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:472–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohm B, Voth M, Geoghegan J, et al. Impact of positron emission tomography on strategy in liver resection for primary and secondary liver tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(5):266–272. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0527-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dierckx R, Maes A, Peeters M, Van De Wiele C. FDG PET for monitoring response to local and locoregional therapy in HCC and liver metastases. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;53(3):336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson GS, Brinkmann F, Soulen MC, Alavi A, Zhuang H. FDG positron emission tomography in the surveillance of hepatic tumors treated with radiofrequency ablation. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(3):192–197. doi: 10.1097/01.RLU.0000053530.95952.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paudyal B, Oriuchi N, Paudyal P, et al. Early diagnosis of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma with 18F-FDG PET after radiofrequency ablation therapy. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(6):1469–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donckier V, Van Laethem JL, Goldman S, et al. [F-18] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a tool for early recognition of incomplete tumor destruction after radiofrequency ablation for liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84(4):215–223. doi: 10.1002/jso.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paudyal B, Paudyal P, Oriuchi N, Tsushima Y, Nakajima T, Endo K. Clinical implication of glucose transport and metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33(5):1047–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 1):427–433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrowsky H, Wildbrett P, Husarik DB, et al. Impact of integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography on staging and management of gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluge R, Schmidt F, Caca K, et al. Positron emission tomography with [(18)F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose for diagnosis and staging of bile duct cancer. Hepatology. 2001;33(5):1029–1035. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JY, Kim MH, Lee TY, et al. Clinical role of 18F-FDG PET-CT in suspected and potentially operable cholangiocarcinoma: a prospective study compared with conventional imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(5):1145–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon CM, Bang S, Chung JB, et al. Usefulness of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in differential diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinomas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(5):759–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corvera CU, Blumgart LH, Akhurst T, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography influences management decisions in patients with biliary cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson CD, Rice MH, Pinson CW, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging in the evaluation of gallbladder carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(1):90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miura F, Asano T, Amano H, et al. New prognostic factor influencing long-term survival of patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery. 2010;148:271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Gomez-Rio M, Llamas-Elvira JM, et al. Positron-emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose for gallbladder cancer diagnosis. Am J Surg. 2004;188(2):171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin D, Suwantarat N, Kwee S, et al. Cushing’s syndrome caused by an ACTH-producing large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):56–58. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butte J, Redondo F, Waugh E, et al. The role of PET-CT in patients with incidental gallbladder cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11(1):585–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemke AJ, Niehues SM, Hosten N, et al. Retrospective digital image fusion of multidetector CT and 18F-FDG PET: clinical value in pancreatic lesions--a prospective study with 104 patients. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(8):1279–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bang S, Chung HW, Park SW, et al. The clinical usefulness of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the differential diagnosis, staging, and response evaluation after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(10):923–929. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225672.68852.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinrich S, Goerres GW, Schafer M, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography influences on the management of resectable pancreatic cancer and its cost-effectiveness. Ann Surg. 2005;242(2):235–24. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000172095.97787.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schick V, Franzius C, Beyna T, et al. Diagnostic impact of 18F-FDG PET-CT evaluating solid pancreatic lesions versus endosonography, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography with intraductal ultrasonography and abdominal ultrasound. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(10):1775–1785. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeWitt J, Devereaux B, Chriswell M, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and multidetector computed tomography for detecting and staging pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):753–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mertz HR, Sechopoulos P, Delbeke D, Leach SD. EUS, PET, and CT scanning for evaluation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(3):367–371. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kauhanen SP, Komar G, Seppanen MP, et al. A prospective diagnostic accuracy study of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, multidetector row computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in primary diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):957–963. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b2fafa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sendler A, Avril N, Helmberger H, et al. Preoperative evaluation of pancreatic masses with positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose: diagnostic limitations. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1121–1129. doi: 10.1007/s002680010182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Chierichetti F, Liessi G, Ferlin G, Pedrazzoli S. Value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the management of patients with cystic tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2001;234(5):675–680. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperti C, Bissoli S, Pasquali C, et al. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography enhances computed tomography diagnosis of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):932–937. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2a29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshioka M, Sato T, Furuya T, et al. Role of positron emission tomography with 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose in evaluating the effects of arterial infusion chemotherapy and radiotherapy on pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(1):50–55. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Bissoli S, Chierichetti F, Liessi G, Pedrazzoli S. Tumor relapse after pancreatic cancer resection is detected earlier by 18-FDG PET than by CT. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(1):131–140. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strobel K, Heinrich S, Bhure U, et al. Contrast-enhanced 18F-FDG PET/CT: 1-stop-shop imaging for assessing the resectability of pancreatic cancer. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(9):1408–1413. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]