Abstract

Objective

To describe, and to test against trial data, a simple and flexible computer program for calculating cardiovascular risk in individual patients as an aid to managing risk factors and prescribing drugs to lower cholesterol concentration and blood pressure.

Design

Descriptive comparison of actual cardiovascular risk in randomised controlled trials of cholesterol reduction with risk predicted by a computer program based on the Framingham risk equation. Comparison of the program’s performance with that of tables and guidelines by means of hypothetical case examples.

Main outcome measures

Average risk of coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction.

Results

The computer program accurately predicted baseline absolute risk in a UK population as well as the relative and absolute reduction in risk from cholesterol lowering for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. The program also allowed a more refined estimate of absolute risk of coronary heart disease than some existing tables and enabled the impact of prescribing decisions to be quantified and costed.

Conclusions

This simple computer program to estimate individuals’ cardiovascular disease risk and display the benefits of intervention should help clinicians and patients decide on the most effective packages of risk reduction and identify those most likely to benefit from modulation of risk factors.

Key messages

The absolute risk of coronary heart disease in any individual is determined by a complex interplay of several risk factors

We developed a simple computer programme based on data from prospective observational studies to estimate individual risk of cardiovascular disease and predict effects of intervention

We compared predicted estimates with actual cardiovascular risk determined from trials of cholesterol reduction

The program accurately predicted baseline absolute risk as well as the relative and absolute reduction in risk from cholesterol lowering for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

The program should help doctors implement guidelines on the use of statins or antihypertensives by identifying individuals most likely to benefit and should enable patients to make informed decisions about which interventions they would wish to pursue

Introduction

Prospective cohort studies have shown that the absolute risk of cardiovascular disease in any individual is determined by a complex interplay of several factors, of which age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, and serum concentrations of total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol are the more important.1 Recent large randomised controlled trials have shown that reducing serum cholesterol concentration reduces the incidence of coronary heart disease events in patients with a history of angina or myocardial infarction2,3 and in middle aged men with a high cholesterol concentration but without symptomatic coronary artery disease.4 As with antihypertensive treatment, the absolute benefit from cholesterol reduction depends on the pretreatment level of cardiovascular risk—individuals with high absolute levels of risk stand to gain the most.5 The problems facing doctors are how to implement the findings of the many clinical trials and cohort studies into everyday clinical practice and how to involve patients in the decision making process.

The interaction between risk factors is not additive but synergistic. Calculations of levels of risk and possible benefits of intervention in any individual are not straightforward and cannot readily be undertaken during a consultation. Attempts to overcome this problem by developing risk charts or tables have been useful,6–9 but these approaches give only broad estimates of risk based on clusters of risk factors. With this approach it is difficult to quantify precisely the predicted risk or, more importantly, the likely consequences of therapeutic intervention in an individual patient.

We have developed an interactive computer program that overcomes some of these limitations. The program, based on standard software, calculates and displays an individual’s absolute and relative risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, or various other end points of cardiovascular disease and can be used to estimate the expected benefit of modifying risk factors. We compare the predictions of the program with data from recent randomised controlled trials and use case examples to illustrate how this or other programs might be used in clinical practice.

Methods

Computer program

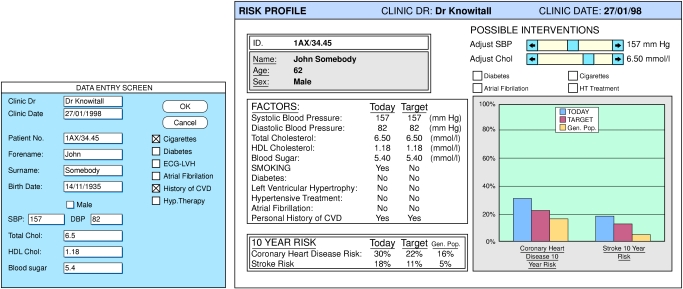

The program (based on a Microsoft Excel version 5.0 workbook and available on a single floppy disk) runs on a personal computer and provides a graphical and numerical display of the risk of cardiovascular outcomes for any given combination of clinical variables. Data on standard risk factors are entered into a simple screen (fig 1). Risks are calculated with logistic regression equations derived from the Framingham populations,10–12 a large cohort in the United States studied prospectively over many years. The program displays an individual’s absolute and relative risk together with an estimate of the change in risk that might follow therapeutic intervention or changes in lifestyle (such as reducing blood pressure or total cholesterol concentration or stopping smoking). In its present form, for use in a clinic, the program displays a 10 year risk for coronary heart disease and stroke. It also displays the predicted risk of coronary heart disease and stroke for the general population—the average risk for a non-smoking subject matched for the patient’s age and sex with age adjusted population mean levels of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure. The data and outcome estimates can be printed. The data are stored in a database, which can be interrogated to provide, for example, information on changes in risk factors over time, success in risk reduction, prescribing policy against risk scores, or the overall burden of cardiovascular disease in a practice population.

Figure 1.

Data entry screen (below) and individual risk profile (right). The graph shows predicted 10 year risk for coronary heart disease and stroke (blue columns); risk for an individual matched for age and sex with population mean levels, adjusted for age, of cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (yellow columns); and the effect of stopping smoking on risk (red columns)

Comparison of program’s predictions

The Framingham coronary heart disease risk function is derived by observing the cumulative number of events of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease among the original Framingham cohort and the subjects of the Framingham offspring study, who were followed for 4-12 years.10–12 The Framingham analysis is therefore designed for use in the setting of primary prevention and forms the basis of some commonly used guidelines and risk tables such as the Sheffield and New Zealand tables.

Our program estimates the benefit of modifying a risk factor on the assumption that, for any given reduction in the level of a particular risk factor (such as cholesterol), risk is reduced to the level of an otherwise equivalent individual whose baseline cholesterol concentration is the same as the new treated level. To determine how the predictions compare with information currently available to prescribers, we used published data from large intervention studies.2–4 These data also form the basis of current recommendations on treatment policies.13 We entered data on the average patient profile (age, cholesterol concentration, systolic blood pressure, smoking, etc) in each trial into the program, together with the observed mean effect on the risk factor profile achieved in the intervention group. We also analysed how the risk estimate generated by the program differed from the risk estimate provided by the Sheffield tables,6,7 which are widely used to estimate risk and are also based on the Framingham data.

Results

Baseline absolute risk

Table 1 shows the five year risk of various end points of cardiovascular disease calculated by our program for a 55 year old man with clinical variables corresponding to the average baseline characteristics of a member of the placebo arm of the West of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS), a primary prevention trial.4 Risks for a smoker and a non-smoker are considered separately. These data are compared with the five year event rates in the placebo arm of the WOSCOPS trial itself, which included both smokers (44%) and non-smokers (56%). For each comparison, we used the closest equivalent end point from the WOSCOPS trial. For all end points, the event rates in the WOSCOPS trial lay between those predicted by the program for smokers and for non-smokers. When applied to individuals with clinical profiles compiled by using average baseline data from the placebo arms of the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S)2 and the cholesterol and recurrent events trial (CARE)3 (trials of secondary prevention) the Framingham risk equation underestimated absolute baseline risk about twofold.

Table 1.

Five year risk of cardiovascular disease in 55 year old men with hypercholes- terolaemia*: prediction by program (based on Framingham study10-12) compared with observed event rates in West of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS)4

| End point | Predicted 5 year risk (%)

|

Observed 5 year event rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smoker | Smoker | ||

| Coronary heart disease† | 7.5 | 11.9 | 9.3 (10.7 for composite end point†) |

| Myocardial infarction‡ | 3.5 | 8.8 | 7.8 |

| Death from coronary heart disease | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Stroke | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

Clinical variables correspond to those of WOSCOPS, which examined 6595 men with mean age 55 years who, at entry to study, had mean serum concentrations of total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol of 7.07 mmol/l and 1.14 mmol/l respectively, had mean systolic blood pressure of 136 mm Hg, and 44% of whom were smoking.

Defined in Framingham study as myocardial infarction, death from coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, and coronary insufficiency. WOSCOPS reported a combined end point of death from coronary heart disease and non-fatal myocardial infarction. A composite end point from WOSCOPS (event rate shown in brackets) comprising definite non-fatal myocardial infarction and death from coronary heart disease plus revascularisation (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and coronary artery bypass graft) may be more comparable to the Framingham definition.

Includes both fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction for predicted event rates. Observed event rate in WOSCOPS is for non-fatal myocardial infarction.

Effects of lowering serum cholesterol concentration

In the WOSCOPS trial, treatment with pravastatin resulted in a 20% reduction in total serum cholesterol concentration and a 5% increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol, with the full effect on lipid concentration being achieved within a few months of starting treatment. Table 2 shows the program’s predicted effects of these changes along with the observed risk reductions in the trial itself. For all the end points considered, both the relative and absolute risk reductions predicted by the program were similar to those observed in the trial and lay well within the reported confidence intervals, although these were wide. The predicted relative risk reduction for subjects with pre-existing cardiovascular disease (secondary prevention) was less accurate, with the program overestimating the benefit compared with that seen in the 4S and CARE trials (table 3).

Table 2.

Effects of cholesterol lowering in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 55 year old men with hypercholesterolaemia*: prediction by computer program (based on Framingham study10-12) compared with observed risk reductions in West of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS)4

| End point | Predicted risk reduction (%)

|

Observed risk reduction (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute risk

|

Relative risk

|

Absolute risk | Relative risk (95% CI) | |||||

| Non-smoker | Smoker | Non-smoker | Smoker | |||||

| Coronary heart disease† | 2.3 | 3.3 | 31 | 28 | 2.5 (3.2 for composite end point†) | 29 (15 to 40) (31 for composite end point†) | ||

| Myocardial infarction‡ | 1.4 | 2.7 | 40 | 31 | 2.0 | 27 (12 to 40) | ||

| Death from coronary heart disease | 0.5 | 0.9 | 46 | 40 | 0.6 | 33 (1 to 55) | ||

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.16§ | 11 (−33 to 40) | ||

Patients in the treatment arm of WOSCOPS received 40 mg pravastatin daily, which resulted in, on average, 20% reduction in total cholesterol concentration and 5% increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration.

Defined in Framingham study as myocardial infarction, death from coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, and coronary insufficiency. WOSCOPS reported a combined end point of death from coronary heart disease and non-fatal myocardial infarction. A composite end point from WOSCOPS (event rate shown in brackets) comprising definite non-fatal myocardial infarction and death from coronary heart disease plus revascularisation may be more comparable to the Framingham definition.

This includes both fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction for predicted event rates. Observed event rate in WOSCOPS is for non-fatal myocardial infarction.

Calculated from table 2 of WOSCOPS report.4

Table 3.

Effects of cholesterol lowering in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: prediction by computer program (based on Framingham study10-12) compared with observed risk reductions in Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S)2 and cholesterol and recurrent events trial (CARE)3

| End point | Predicted reduction in relative risk (%)

|

Observed reduction (95% CI) in relative risk (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||

| Non-smoker | Smoker | Non-smoker | Smoker | |||

| Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S)* | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 50 | 39 | 58 | 47 | 33 non-fatal‡ 48 fatal | |

| Death from coronary heart disease | 55 | 49 | 62 | 58 | 42 (27 to 54) | |

| Cholesterol and recurrent events trial (CARE)† | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 41 | 32 | 49 | 39 | 23 (4 to 39) non-fatal 37 (−5 to 62) fatal | |

| Death from coronary heart disease | 46 | 40 | 56 | 49 | 20 (−5 to 39) | |

4S trial included 4444 subjects (81% men, 26% current smokers) with angina or previous myocardial infarction. At entry, average age was 58 years in men and 60 years in women. Mean serum concentrations of total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol were 6.75 mmol/l and 1.19 mmol/l respectively, and mean systolic blood pressure was 139 mm Hg. In the treatment arm simvastatin 10-40 mg produced an average reduction of 25% in total cholesterol concentration and an 8% increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration.

CARE trial studied 4159 subjects with myocardial infarction (86% men, 21% active smokers). At entry, average age was 59 years. Mean baseline serum concentrations of total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol were 5.40 mmol/l and 1.01 mmol/l respectively, and average systolic blood pressure was 129 mm Hg. In the treatment arm pravastatin 40 mg daily produced a 20% reduction in total cholesterol concentration and a 5% increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration.

Comparison with Sheffield tables

The Sheffield tables and our risk program are formulated from the same original data. Table 4 shows how treatment decisions might vary depending on which system was used to determine whether a patient should receive a statin (using a 55 year old smoker with a cholesterol concentration of 7.4 mmol/l as an example). Because the Sheffield tables treat hypertension as a dichotomous variable (present or absent) and (as commonly used) assume an average concentration of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, they predict an artificially high risk for some patients and an artificially low risk for others.

Table 4.

Effect of high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and systolic blood pressure on 10 year risk of coronary heart disease. Unless stated otherwise, values are the computer program’s predictions of 10 year risk (%) of coronary heart disease in a 55 year old male smoker with serum total cholesterol concentration of 7.4 mmol/l.

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 126 | 136 | 146 | 156 | 166 | 176 | 186 | |

| High density lipoprotein concentration (mmol/l): | |||||||

| 0.8 | 30* | 32* | 35* | 37* | 39 | 40 | 42 |

| 0.9 | 27 | 30* | 32* | 34* | 36 | 37 | 39 |

| 1.0 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 31* | 33 | 35 | 37 |

| 1.1 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 33 | 34 |

| 1.2 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 29† | 31 | 32 |

| 1.3 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 27† | 29† | 30 |

| 1.4 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 25† | 27† | 29† |

| Statin treatment based on Sheffield tables‡ | No | No | No§ | No§ | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Patients who might be undertreated if standard Sheffield tables are used as basis for prescribing statins.

Patients who might be overtreated if standard Sheffield tables are used as basis for prescribing statins.

Sheffield tables advocate statin treatment at a threshold risk of 30% over 10 years (roughly equivalent to 3% a year). The tables assume that high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration is 1.15 mmol/l in men and that systolic blood pressure is either 139 mm Hg if there is no hypertension, or will be controlled to 160 mm Hg if hypertension is present. These simplifications lead to overestimation of risk in some patients and underestimation in others.

For this analysis, we have taken “hypertension” to mean a systolic blood pressure of >160 mm Hg. If a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg was taken as the cut off, the “treatment decision” in these two columns might be altered to “Yes.”

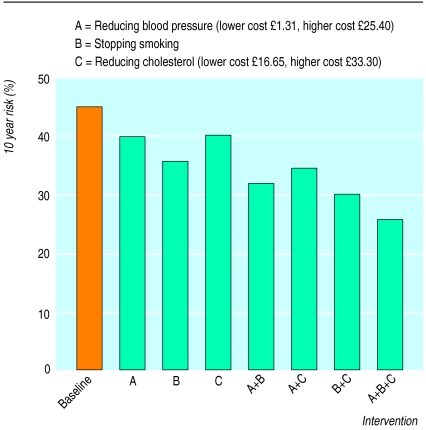

Modulation of individual risk factors

If the aim of treatment is to reduce risk, it is clear that this might be achieved in several different ways. Figure 2 shows the risk for a 69 year old male smoker with a blood pressure of 170/90 mm Hg, total cholesterol concentration of 7.4 mmol/l, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol of 1.0 mmol/l. His 10 year absolute risk of coronary heart disease is 45%, and his 10 year absolute risk of stroke is 18%. A series of options to reduce overall risk is presented and costed.

Figure 2.

Ten year risk of coronary heart disease for a 69 year old male smoker with baseline systolic blood pressure of 170 mm Hg, total cholesterol concentration of 7.4 mmol/l, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration of 1.0 mmol/l. Predicted risk reductions are for reducing systolic blood pressure by 20 mm Hg and reducing total cholesterol by 20%. Costs for 1 month’s treatment (from British National Formulary) are based on assumption that two drugs would be required to achieve 20 mm Hg reduction in blood pressure and that a statin alone would decrease cholesterol concentration by about 20%. The lower cost shown for lowering blood pressure is for bendrofluazide 2.5 mg and atenolol 50 mg; higher cost shown is for lisinopril 10 mg and amlodipine 10 mg. Lower cost for lowering cholesterol is for simvastatin 10 mg; higher cost is for simvastatin 20 mg

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in Britain. Prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke is an important public health challenge and one that doctors and patients consider a priority. Preventive measures of proved efficacy include reducing hypertension,14–16 lowering blood cholesterol concentration,2–4 and stopping smoking.17 Many doctors and their patients will have discussed the various treatment options and tried to assess which would be most appropriate. However, the interaction between risk factors is complex, and the quantitative benefits on health of treatments or lifestyle changes in any individual are not intuitive and cannot easily be presented to patients in an accessible form. This is likely to become more of a problem as new risk factors, such as genetic predisposition, are identified. To overcome this problem we have devised a simple computer program to run on a personal computer or local network. It is based on the Framingham data and can be used to calculate an individual’s level of risk and show the predicted effects of intervention. The predictions of the program are consistent with the published results of major studies and, as such, offer simple guidance on treatment according to best available evidence.

Tables and guidelines

A major driving force behind the development of risk tables and treatment guidelines has been the high cost of statins.18–20 The Standing Medical Advisory Committee has issued recommendations for the use of statins for secondary prevention in Britain13 and has advocated their use in people without overt vascular disease who have an annual risk of coronary heart disease risk of 3% or higher. To assess when this risk level has been crossed, as many risk factors as possible should be considered. This presents a problem for tables and paper guidelines. For example, the failure of such guides to present blood pressure, total cholesterol concentration, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration as continuous variables may lead to discrepancy with the original Framingham data on which the tables are based. This could lead to undertreatment of some individuals and overtreatment of others (table 4).

Furthermore, because of the complex interaction of risk factors, modifying one factor will greatly alter the potential importance of others. Thus, for a patient above a threshold risk for treatment, an acceptable reduction in risk might be achieved by a fall in blood pressure of 10 mm Hg by drug treatment, a small rise in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration by increased exercise, a 15% fall in total cholesterol by treatment with a statin, or a combination of a small effect on each of these (fig 2). While tables and guidelines have attempted to integrate risk factors to produce an overall estimate of risk, they have tended to link this estimate to decisions about intervention in one particular area (cholesterol lowering) rather than encouraging the development of treatment packages designed to achieve a target level of risk in an individual.

Advantages of computer based system

The advantages of the program described here are that

It uses the full Framingham risk score rather than an approximation of it

It displays the absolute risk of coronary heart disease (or other end points of cardiovascular disease) over any period between four and 12 years

It can also be used to estimate the relative risk of coronary heart disease by comparing an individual’s risk with that of healthy individuals of equivalent sex and age with mean population levels of cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol

It can be used to quantify the maximum benefit derived from modifying risk factors, whether this be lowering total cholesterol, reducing blood pressure, or stopping smoking

It can be used to set individualised treatment targets for blood pressure or cholesterol concentration based on predicted effects on overall risk profile

It may be used to generate a database of value for clinical audit, monitoring prescribing, or research.

The program can be used during a consultation to allow the patient to see immediately the predicted health benefits of changes in lifestyle (stopping smoking) or drug treatment. A target level of risk reduction might be achieved by several different routes, and the patient could participate in deciding which route to follow. He or she might also be in a better position to decide whether to continue with a drug producing an unwanted side effect if the predicted maximum desired effect on health is clearly displayed and quantified. It would be interesting to determine how individuals respond to the presentation of absolute and relative risks in this way.21

Limitations of computer program

The fact that we used the Framingham data to predict successfully the event rate in the placebo arm of the WOSCOPS study22 suggests that the Framingham database is directly applicable to a UK population without clinically evident atherosclerotic disease. In predicting the effects of an intervention, the program assumes that, on lowering blood pressure, adjusting cholesterol, stopping smoking, etc, individuals adopt the new level of risk predicted from the cohort study. The evidence supports this assumption,23,24 but the program may overestimate the benefits of reducing blood pressure on coronary heart disease14 and, possibly, underestimate the benefits of lowering total cholesterol concentration with statins.22

We compared computer predictions with outcome studies of cholesterol lowering. Although the computer predictions and observed results are broadly comparable, the statistical validity of our approach may be open to question. For the computer predictions, we took the mean patient data from each trial and treated this as a hypothetical individual to generate a predicted outcome using definitions of end points that were similar to, but not always identical with, those of the trials. Clearly, the trials included many individuals who differed substantially from the “average” patient, and it is possible that the program predictions may not be applicable to certain patient groups (or, indeed, to certain ethnic minorities) or that the program might not have generated the same risk scores if individual patient data from the trials had been entered. However, practising clinicians are presented with the published data, not raw individual data, and they, and the bodies producing guidelines, act on the mean data presented. In this respect the program is similar to current practice but has the advantage that it applies the results in a consistent manner with a perfect memory.

The program is clearly appropriate for use in primary prevention, but it is less valid in the setting of secondary prevention. However, secondary prevention presents less of a therapeutic dilemma for doctors.

Conclusions

Our simple computer program, based on the Framingham data, can be used to determine levels of absolute and relative risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals and to estimate the effect on risk of proposed interventions. The results are consistent with the results of the major intervention studies and could be used as an individualised evidence based guide to prescribing policy, and to involve patients in the decision making process. The program would focus attention away from single risk factors towards a more integrated approach to preventing cardiovascular disease. If it was used in primary care its implementation might also allow creation of a unified database of local and possibly national value.

Acknowledgments

Those involved in developing the program and the Vascular Risk Clinic at University College Hospital include Professors John Martin and John Deanfield; Drs Raymond MacAllister, Kiran Bhagat, and Ian Day; and Mike Gahan and Ryan Pervan.

Footnotes

Funding: ADH is supported by a Gerry Turner Intermediate fellowship of the British Heart Foundation.

Potential conflict of interest: Copyright for the program is currently held by John Martin and PV.

References

- 1.Dawber TR. The Framingham study. The epidemiology of atherosclerotic disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, Macfarlane PW, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolaemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson R, Beaglehole R. Evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia. Lancet. 1995;344:1440–1441. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haq U, Jackson PR, Yeo WW, Ramsay LE. Sheffield risk and treatment table for cholesterol lowering for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1995;346:1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92477-9. 1996;348:1251-2.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsay LE, Haq IU, Jackson PR, Yeo WW, Pickin CM, Payne JN. Targeting lipid-lowering drug therapy for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: an updated Sheffield table. Lancet. 1996;348:387–388. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)05516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson R, Barham P, Bills J, McLennan S, Macmahon S, Maling T. Management of raised blood pressure in New Zealand: a discussion document. BMJ. 1993;307:107–110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyorala K, De Backer G, Graham I, Poole-Wilson P. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the task force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1300–1301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1990;121:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson KM, Wilson PWF, Odell PM, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83:356–362. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Blanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winyard G. SMAC statement on the use of statins. London: Department of Health; 1997. (EL(97)41 HCD 750 IP Aug 97). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins R, Peto R, Macmahon S, Hebert P, Fiebach NH, Eberlein KA, et al. Blood pressure, stroke and coronary heart disease. Part 2, short term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the systolic hypertension in the elderly programme (SHEP) JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhager WH, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson JE, Tosteson H, Ridker PM, Satterfield S, Hebert P, O’Connor GT, et al. The primary prevention of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1406–1416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205213262107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haq IU, Ramsay LE, Pickin DM, Yeo WW, Jackson PR, Payne JN. Lipid-lowering for the prevention of coronary heart disease: what policy now? Clin Sci. 1996;91:399–413. doi: 10.1042/cs0910399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fremantle N, Barbour R, Johnson R, Marchment M, Kennedy A. The use of statins: a case of misleading priorities? BMJ. 1997;315:826–828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7112.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muldoon MF, Criqui MH. The emerging role of statins in the prevention of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1997;315:1554–1555. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7122.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skolbekken J-A. Communicating the risk reduction achieved by cholesterol reducing drugs. BMJ. 1998;316:1956–1958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7149.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS) Circulation. 1998;97:1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law MR, Wald NJ, Thompson SG. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994;308:367–373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould AL, Rossouw JE, Santanello NC, Heyse JF, Furberg CD. Cholesterol reduction yields clinical benefit. Impact of statin trials. Circulation. 1998;97:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]