Gene transcriptional activation of the human genome in response to physiological and environmental stimuli requires chromatin structure changes defined by enzymes that modify chromatin and directed by proteins that interact with chromatin in a modification-sensitive manner. This highly complex system operates with a large number of chemical modifications on chromatin (both DNA and histones) and transcription-associated proteins.1 Of these, lysine acetylation functions to facilitate chromatin opening and productive transcriptional machinery assembly required for gene activation. These activities are directed by the acetyl-lysine binding activity of the bromodomain (BrD), a fundamental molecular mechanism for gene transcriptional activation that was discovered in the structural biology study of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) transcriptional co-activator PCAF.2 The human genome encodes a total of 61 bromodomains in 46 chromatin regulator proteins, some of which comprise multiple bromodomains.2 As a key epigenome reader, the bromodomain is almost solely responsible for binding to acetylated-lysine in histones and transcription-associated proteins, thereby orchestrating gene transcription in chromatin in an ordered fashion.2 Recent studies show that pharmacological small molecule modulation of the acetyl-lysine binding activity of BrD proteins such as the BET (Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal domain) family protein BRD4 and the HAT co-activator CBP/p300 dictates gene transcription outcome in disease models3 such as multiple myeloma, lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, mixed lineage leukemia, HIV-associated kidney disease, and ischemia, indicating these bromodomains as attractive drug targets for diseases including cancer and inflammation.

All bromodomains share an evolutionarily conserved structural fold consisting of a left-handed four-helix bundle with two inter-helix-connecting loops, termed ZA and BC loops, which together constitute the acetyl-lysine binding pocket.2 Given high degree variations in the amino acid sequence and structural flexibility of the ZA and BC loops, the acetyl-lysine binding pocket poses a challenge to developing potent and selective small molecule inhibitors for bromodomains. In an effort to explore the physicochemical basis for small molecule inhibition of bromodomains, Vidler et al conducted a family-wide survey of the druggability landscape of the acetyl-lysine binding site in human bromodomains.4

Generally speaking, a target protein is considered druggable if it can be modulated in vivo by a drug-like molecule.5 Structure-based target druggability assessment, however, uses a less restrictive definition of druggability, namely the ability of a protein to bind to drug-like molecules with high affinity. While related, the two definitions are not identical. A high-affinity drug-like ligand may not be active in vivo for a number of reasons including bioavailability. Structure-based druggability assessment predicts a degree by which a ligand-binding site in a protein is able to bind to a drug-like molecule with high affinity.5

The recent availability of several validation sets of druggable versus undruggable targets has led to the development of a number of computational methods.5 Most methods combine geometrical and physicochemical properties of the protein surface to define mainly the size, shape, and hydrophobicity of binding pockets, although other properties may also be included.5 Among these SiteMap is one of the most widely used,5 and is also the one used in the Vidler study of bromodomains. SiteMap combines binding site identification with druggability assessment. First, a binding site is identified as a set of reasonably enclosed points that are outside the protein; groups of these points define ‘sites’ that are characterized their size, degree of enclosure by the protein, hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, and other properties. A SiteScore is defined using a subset of these properties and used for binding-site identification. A different score, Dscore, which uses the same properties as the SiteScore but with different coefficients, is then used to assess the druggability of the predicted binding sites. Hydrophobicity plays a larger role in Dscore than in SiteScore due to the fact that “undruggable” sites typically are much more hydrophilic and much less hydrophobic than “druggable” sites.

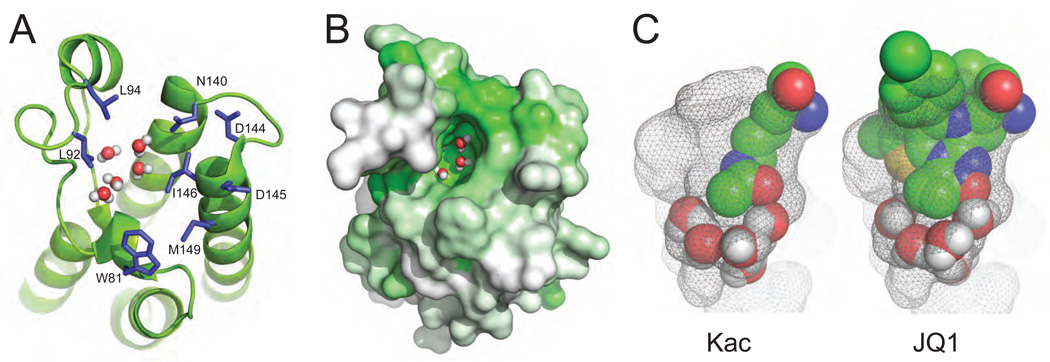

Using SiteMap, Vidler and coworkers assessed the druggability of human bromodomains using 105 crystal structure entries available in Protein Data Bank, which encompass 33 of the 61 human bromodomains. Eight residues near the acetyl-lysine binding site of the BET protein BRD4 (i.e. W81, L92, L94, N140, D144, D145, I146, and M149) were utilized as references (Figure 1A,B). In addition to the key residues that interact with the bound acetyl-lysine, five water molecules are found at the conserved sites within the ligand-binding pocket in many different bromodomains, suggesting that they are an integrated part of the acetyl-lysine binding pocket (Figure 1C). As such, these bound water molecules were included in the SiteMap analysis of protein druggability. Superimpositions of these structures lead to classification of the human bromodomain family into 9 groups that show distinctive structural features. The Dscore analysis further predicted that the BET bromodomains, Group 1, are highly druggable, which is in an agreement with the fact that several highly potent BET bromodomain-specific small molecule inhibitors such as JQ1, MS417 and iBET have been reported in the literature.3, 6 Group 2, which consists of the bromodomains from transcriptional cofactor proteins GCN5, PCAF, FALZ, and CECR2, show a highly predicted druggability. Low micromolar affinity inhibitors for this group of bromodomains have also been reported,6 which represent attractive drug targets for future drug design efforts. Note that although the CBP/p300 bromodomain shows marked variations in structural features as compared to the other groups, it has intermediate druggability. This prediction is supported by the recent development of the CBP bromodomain inhibitors using target structure-guided methods.3,6 The prediction further reveals that other groups of bromodomains appear less druggable than the BET family bromodomains. These groups and their structural correlations were depicted in a bromodomain phylogenetic tree.

Figure 1. Structural features of the acetyl-lysine binding pocket of the bromodomain.

(A) The three-dimensional structure of the first bromodomain of human BRD4 (BRD4-BD1) (pdb code 3mxf), illustrating key amino acid residues, and five bound water molecules located at the acetyl-lysine binding pocket. The side chains of these residues are color-coded by atom type. (B) Surface representation of the BRD4-BD1 that is colored according to amino acid sequence conservation over the entire human bromodomain family (green is more conserved, whereas white is not conserved). (C) Acetyl-lysine (left) and a small molecule bromodomain inhibitor, JQ1 (right) shown when bound in the acetyl-lysine binding pocket (pdb codes 3uvx and 3mxf, respectively). The ligands, as well as bound water molecules are depicted in colored spheres according to atom type (red, blue, green, yellow and white for oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, and hydrogen, respectively). The ligand binding site in the bromodomain protein is defined by mesh.

One of the limitations of SiteMap, and most druggability assessment methods, is that the druggability measure corresponds to the predicted binding site, which may or may not be an accurate representation of the true binding site for a ligand. For instance, it is possible that a ligand will exploit multiple neighboring sites that are considered independent by SiteMap, which might results in greatly increased druggability.

While this study represents the first family-wide druggability analysis for bromodomains, some predictions shall be interpreted with caution. First, as reported previously, the inter-helical ZA and BC loops of bromodomains are highly flexible.2 Local conformational changes in these loops upon binding to a small-molecule ligand could result in changes in the pocket volume and enclosure, leading to a different Dscore value. Consequently, new predictions of druggability score could vary as more available bromodomain structures are included in calculations. Second, possible contribution of secondary cavities adjacent to the acetyl-lysine binding site was not fully explored in this study. Such neighboring cavities could provide new opportunities to improve affinity for small molecules. Lastly, as more druggability prediction programs such as Ffocket, and MAPPOD5 become capable of handling bound water molecules, it will be interesting to compare results obtained with different computational methods. This will enable one to validate and even further improve the fidelity of such predictions.

As a distinct class of protein-protein interaction (PPI) domains that function to regulate gene transcription, bromodomains contrast with the classical highly-druggable drug targets such as protein kinases, GPCRs, and proteases7. In GPCRs the ligand-binding pockets generally are deeply buried in the protein and often nearly fully enclosed, which gives them more contacts with the protein for the same pocket volume7. In kinases the pockets are large and very deep (ATP-binding site)7, thereby providing many contacts with the protein for the size of the ligand. In comparison, the acetyl-lysine binding pockets in bromodomains are not as large, deep, and enclosed as those of these highly-druggable targets. As such, bromodomains probably lie in between these highly-druggable targets and difficult targets such as protein-protein interaction surfaces. Nevertheless, it is difficult to perform a quantitative comparison due to the fact that druggability measures are merely trying to classify targets as "druggable", "difficult", and "undruggable", rather than correctly rank targets within one category.

It is worth noting that what one considers druggable now is biased by the type of molecules that have been used as starting points for drug discovery7. Discovery of new types of molecules may lead to redefinition of what is druggable. For example it has been shown that one can define libraries of small molecules that have a higher chance of inhibiting PPIs.7 For this reason, it is important to emphasize that eventually one needs to attempt the targeting of all medically relevant bromodomains (and targets in general), not just those that are currently considered druggable. Accordingly, the classification of druggability of bromodomains is useful as it predicts which ones could be targeted using current approaches (i.e. low hanging fruit), and which ones would require new developments before one could successfully target them (e.g. different small-molecule libraries such as the case for PPIs). They certainly should not be simply abandoned because they seem intractable in the light of current druggability estimates.

As a parallel in drug discovery that is moving from highly druggable targets such as kinases and GPCRs to more challenging PPI targets, rapidly growing ligand design efforts for bromodomains are expected to progress from targeting a few druggable bromodomains to more difficult ones. The outcome of these studies will undoubtedly enable us to validate members of this new class of drug targets and develop more effective targeted epigenetic therapies for human diseases including cancer and inflammation.

Acknowledgments

The work was in part supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (to M.-M.Z.).

References

- 1.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Dhalluin C, Carlson JE, Zeng L, He C, Aggarwal AK, Zhou MM. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature. 1999;399:491–496. doi: 10.1038/20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Filippakopoulos P, Picaud S, Mangos M, Keates T, Lambert JP, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Felletar I, Volkmer R, Muller S, Pawson T, Gingras AC, Arrowsmith CH, Knapp S. Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell. 2012;149:214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jacobson RH, Ladurner AG, King DS, Tjian R. Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science. 2000;288:1422–1425. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Owen DJ, Ornaghi P, Yang JC, Lowe N, Evans PR, Ballario P, Neuhaus D, Filetici P, Travers AA. The structural basis for the recognition of acetylated histone H4 by the bromodomain of histone acetyltransferase Gcn5p. EMBO J. 2000;19:6141–6149. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sanchez R, Zhou MM. The role of human bromodomains in chromatin biology and gene transcription. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:659–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zeng L, Zhou MM. Bromodomain: an acetyl-lysine binding domain. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Borah JC, Mujtaba S, Karakikes I, Zeng L, Muller M, Patel J, Moshkina N, Morohashi K, Zhang W, Gerona-Navarro G, Hajjar RJ, Zhou MM. A small molecule binding to the coactivator CREB-binding protein blocks apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Chem Biol. 2011;18:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dawson MA, Prinjha RK, Dittmann A, Giotopoulos G, Bantscheff M, Chan WI, Robson SC, Chung CW, Hopf C, Savitski MM, Huthmacher C, Gudgin E, Lugo D, Beinke S, Chapman TD, Roberts EJ, Soden PE, Auger KR, Mirguet O, Doehner K, Delwel R, Burnett AK, Jeffrey P, Drewes G, Lee K, Huntly BJ, Kouzarides T. Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, Chesi M, Schinzel AC, McKeown MR, Heffernan TP, Vakoc CR, Bergsagel PL, Ghobrial IM, Richardson PG, Young RA, Hahn WC, Anderson KC, Kung AL, Bradner JE, Mitsiades CS. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mertz JA, Conery AR, Bryant BM, Sandy P, Balasubramanian S, Mele DA, Bergeron L, Sims RJ. Targeting MYC dependence in cancer by inhibiting BET bromodomains. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16669–16674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108190108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang G, Liu R, Zhong Y, Plotnikov AN, Zhang W, Zeng L, Rusinova E, Gerona-Nevarro G, Moshkina N, Joshua J, Chuang PY, Ohlmeyer M, He JC, Zhou MM. Down-regulation of NF-kappaB transcriptional activity in HIV-associated kidney disease by BRD4 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28840–28851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, Rappaport AR, Herrmann H, Sison EA, Magoon D, Qi J, Blatt K, Wunderlich M, Taylor MJ, Johns C, Chicas A, Mulloy JC, Kogan SC, Brown P, Valent P, Bradner JE, Lowe SW, Vakoc CR. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidler LR, Brown N, Knapp S, Hoelder S. Druggability Analysis and Structural Classification of Bromodomain Acetyl-lysine Binding Sites. J Med Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1021/jm300346w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Cheng AC, Coleman RG, Smyth KT, Cao Q, Soulard P, Caffrey DR, Salzberg AC, Huang ES. Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hajduk PJ, Huth JR, Tse C. Predicting protein druggability. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1675–1682. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03624-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Halgren TA. Identifying and characterizing binding sites and assessing druggability. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:377–389. doi: 10.1021/ci800324m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Krasowski A, Muthas D, Sarkar A, Schmitt S, Brenk R. DrugPred: A Structure-Based Approach To Predict Protein Druggability Developed Using an Extensive Nonredundant Data Set. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2829–2842. doi: 10.1021/ci200266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Le Guilloux V, Schmidtke P, Tuffery P. Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nisius B, Sha F, Gohlke H. Structure-based computational analysis of protein binding sites for function and druggability prediction. J Biotechnol. 2012;159:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Schmidtke P, Barril X. Understanding and Predicting Druggability. A High-Throughput Method for Detection of Drug Binding Sites. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5858–5867. doi: 10.1021/jm100574m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Seco J, Luque FJ, Barril X. Binding Site Detection and Druggability Index from First Principles. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2363–2371. doi: 10.1021/jm801385d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Sheridan RP, Maiorov VN, Holloway MK, Cornell WD, Gao YD. Drug-like Density: A Method of Quantifying the "Bindability" of a Protein Target Based on a Very Large Set of Pockets and Drug-like Ligands from the Protein Data Bank. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:2029–2040. doi: 10.1021/ci100312t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Sugaya N, Ikeda K. Assessing the druggability of protein-protein interactions by a supervised machine-learning method. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Volkamer A, Kuhn D, Grombacher T, Rippmann F, Rarey M. Combining Global and Local Measures for Structure-Based Druggability Predictions. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:360–372. doi: 10.1021/ci200454v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Dekker FJ, Ghizzoni M, van der Meer N, Wisastra R, Haisma HJ. Inhibition of the PCAF histone acetyl transferase and cell proliferation by isothiazolones. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hewings DS, Wang M, Philpott M, Fedorov O, Uttarkar S, Filippakopoulos P, Picaud S, Vuppusetty C, Marsden B, Knapp S, Conway SJ, Heightman TD. 3,5-dimethylisoxazoles act as acetyl-lysine-mimetic bromodomain ligands. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6761–6770. doi: 10.1021/jm200640v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nicodeme E, Jeffrey KL, Schaefer U, Beinke S, Dewell S, Chung CW, Chandwani R, Marazzi I, Wilson P, Coste H, White J, Kirilovsky J, Rice CM, Lora JM, Prinjha RK, Lee K, Tarakhovsky A. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010;468:1119–1123. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sachchidanand, Resnick-Silverman L, Yan S, Mutjaba S, Liu WJ, Zeng L, Manfredi JJ, Zhou MM. Target structure-based discovery of small molecules that block human p53 and CREB binding protein association. Chem Biol. 2006;13:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zeng L, Li J, Muller M, Yan S, Mujtaba S, Pan C, Wang Z, Zhou MM. Selective small molecules blocking HIV-1 Tat and coactivator PCAF association. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2376–2377. doi: 10.1021/ja044885g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Billingsley ML. Druggable Targets and Targeted Drugs: Enhancing the Development of New Therapeutics. Pharmacology. 2008;82:239–244. doi: 10.1159/000157624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mason JS, Bortolato A, Congreve M, Marshall FH. New insights from structural biology into the druggability of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Metz A, Ciglia E, Gohlke H. Modulating Protein-Protein Interactions: From Structural Determinants of Binding to Druggability Prediction to Application. Curr Pharm Des. 2012 doi: 10.2174/138161212802651553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Reynes C, Host H, Camproux AC, Laconde G, Leroux F, Mazars A, Deprez B, Fahraeus R, Villoutreix BO, Sperandio O. Designing Focused Chemical Libraries Enriched in Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors using Machine-Learning Methods. Plos Comput Biol. 2010:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Russ AP, Lampel S. The druggable genome: an update. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1607–1610. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03666-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Villoutreix BOL, C M, Lagorce D, Laconde G, Sperandio O. A leap into the chemical space of Protein-Protein Interaction inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2012 doi: 10.2174/138161212802651571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]