Abstract

Recent reports indicate that cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery is infrequent, but it is an important and preventable problem. This type of bleeding is thought to occur secondary to venous infarction, but the exact pathogenetic mechanisms are unknown. This report details the case of a 48-year-old woman who developed remote cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery. The patient presented with a herniated lumbar disc, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis, and underwent multiple-level laminectomy, discectomy, and transpedicular fixation. The dura mater was opened accidentally during the operation. There were no neurologic deficits in the early postoperative period; however, 12 h postsurgery the patient complained of headache. This became more severe, and developed progressive dysarthria and vomiting as well. Computed tomography demonstrated small sites of remote cerebellar hemorrhage in both cerebellar hemispheres. The patient was treated medically, and was discharged in good condition. At 6 months after surgery, she was neurologically normal. The case is discussed in relation to the ten previous cases of remote cerebellar hemorrhage documented in the literature. The only possible etiological factors identified in the reported case were opening of the dura and large-volume cerebrospinal fluid loss.

Keywords: Cerebellar hemorrhage, Dural injury, Hemorrhagic infarction, Spinal surgery

Introduction

Cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery is extremely rare, but is a very serious clinical problem due to the location of the bleeding. Some authors suggest that remote cerebellar hemorrhage (RCH) or hemorrhagic infarction occurs due to venous infarction, but the pathophysiology and etiology of this condition are unknown [4, 7, 13, 14, 16]. It has been proposed that cerebellar sag resulting from intraoperative or postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage might stretch and occlude the bridging cerebellar veins that course cephalad, leading to hemorrhagic venous infarction [4, 9, 14, 16]. Peroperative patient positioning is another factor that is widely suspected to contribute to RCH, but the relevance of this is unclear [4, 12]. We report a case in which RCH occurred after spinal surgery, and discuss possible causative factors.

Case

A 48-year-old woman presented with pain in her lower back and both legs. Investigation revealed a herniated disc at L4–L5, stenosis of the lumbar spinal canal, and spondylolisthesis at L4–L5. She was operated in prone position via a posterior approach. The surgery involved L3–L5 laminectomies, L4–L5 discectomy, and screw fixation of the L3–L5 pedicles. The dura mater was damaged intraoperatively, and was sutured in watertight fashion.

Approximately 100 ml of CSF escaped before the dura was closed. When this accidental opening of the dura occurred, the patient’s blood pressure dropped immediately, and the decrease was attributed to the CSF leakage. The anesthesiologist administered routine treatment for hypotension (10 mg intravenous ephedrine sulfate), and blood pressure returned to normal range within approximately 10 min. Prior to closure, a hemovac drain was placed in the epidural space.

When the patient awoke from anesthesia, she was neurologically intact. Her blood pressure was normal in the immediate postoperative period. At 12 h after surgery she complained of headache, and over the next 12 h she exhibited progressive dysarthria, developed a severe headache, and began vomiting. By the end of the first day, the patient was conscious but only responsive to commands. In the first 24 h after surgery, 580 ml of serosanguineous fluid were removed via the hemovac drain.

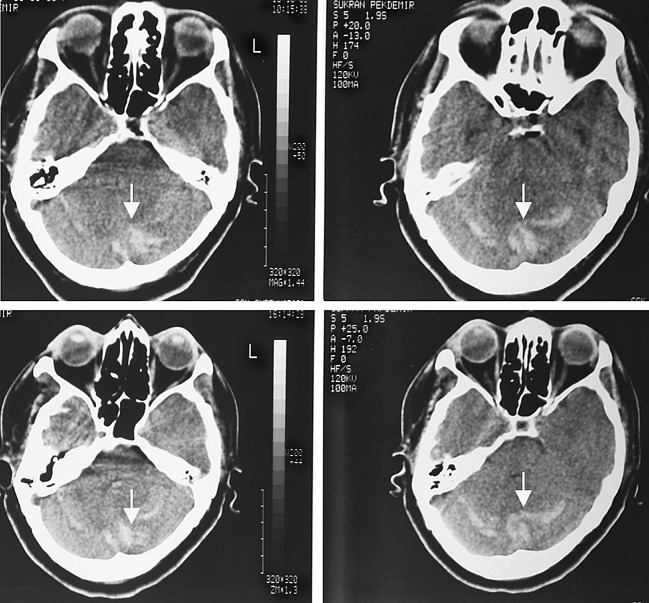

Cranial computed tomography (CT) at 24 h showed small sites of hemorrhage in both cerebellar hemispheres, just below the tentorium (Fig.1). The results of laboratory investigations, including platelet count, and a clotting screen, were all in the normal range.

Fig. 1.

Cranial computed tomography scanning done 24 h after spinal surgery showed cerebellar hemorrhage or venous infarction in the cerebellum (arrows)

The patient was managed conservatively with anti-edema treatment (4 mg intravenous dexamethasone every 6 h), analgesics, and bed rest. Her neurological status did not deteriorate further after hemorrhage was detected. Repeat CT at 48 h postsurgery showed no enlargement of the hemorrhage sites and no hydrocephalus. Nine days after the operation, the patient was discharged in good condition with full mobility and with no neurologic deficits. At 6 months after surgery, she was neurologically normal.

Discussion

Intracerebral hematoma after craniotomy is one of the most common and important complications in neurosurgery practice [2, 6, 10, 14]. Some of these hematomas occur at the surgical site, whereas others develop at remote locations. Hemorrhage after cranial or spinal surgery can occur in the intracerebral, cerebellar, epidural, or subdural compartments. Numerous authors have reported cases in which RCH developed as a delayed complication of spinal surgery [1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13]. Chadduck [3] first described RCH after a spinal procedure in 1981. Most recently, Thomas et al. [13] documented a case in which supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage developed after spinal operations. There has been increased interest in RCH in the past 10 years, but no specific etiological factors have yet been identified for this type of hemorrhage after spinal surgery.

We conducted a detailed literature review of a total of ten cases of RCH that have been reported to date, and found no correlations between RCH and age, sex, pathology operated, or type of interventions performed [1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13] (Table 1). Seven of these patients were male and three were female, and the age range was 34–75 years (median, 50 years). Four individuals were operated for intradural pathologies, and the other six for extradural pathologies. RCH was detected between 16 and 120 h (median, 47 h) after surgery.

Table 1.

Clinical parameters and outcome for the ten previously reported cases of remote cerebellar hemorrhage and the current case

| Primary pathology/Author | Age (years)/Sex | Patient positioning | Time of infarction | Hemorrhage location | Treatment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical spinal stenosis (ED)a Chadduck [3] | 59/M | Sitting | 48 h postoperative | Left CH+Hydrocephalus | Postoperative fossa decomp.+EVD | Alert, conversive, able to eat (residual disability) |

| Revision of cervical fusion (ED)a Mikawa et al. [8] | 75/M | Supine | 16 h postoperative | Both CHs | Postoperative fossa decomp.+EVD | Exitus |

| Lumbar scoliosis (ED)a Andrews and Koci [1] | 36/M | Prone | 36 h postoperative | Both CHs+Hydrocephalus | EVD | Quadraparetic, min. hand motor function (residual disability) |

| Postdiscectomy syndrome (ED)a Gobel et al. [5] | 40/F | Prone | 48 h postoperative | Right CH+Hydrocephalus | Postoperative fossa decomp.+EVD | Recovery |

| Spondylolisthesis (ED)a Gobel et al. [5] | 57/F | Prone | 72 h postoperative | Both CHs+Hydrocephalus | EVD | Mn (6 weeks postoperative)+sinus thrombosis (4 months postoperative) (residual disability) |

| Cervical intramed. tumor (ID) Satake et al. [11] | 62/M | Prone | 18 h postoperative | Cerebell. and supracerebellar layer | Postoperative fossa decomp. | Diplopia, dizziness, and nausea (3 months postoperative) (residual disability) |

| Cervical schwannoma (ID) Morandi et al. [9] | 34/M | Prone | 18 h postoperative | Right CH+left temporal hemorr. | Anti-edema drugs and serial imaging | Recovery |

| T9–T10 herniated disc (ID) Friedman et al. [4] | 43/M | Prone | 48 h postoperative | Right CH | Anti-edema drugs and serial imaging | Mild dysarthria and ataxia (residual disability) |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis (ED)a Friedman et al. [4] | 56/M | Prone | 48 h postoperative | Both CHs | Anti-edema drugs and serial imaging | Mild dysarthria and ataxia (residual disability) |

| Thoracolumbar tumor (ID) Thomas et al. [13] | 38/F | Prone | 120 h postoperative | Supra-infratentorial | Anti-edema drugs and serial imaging | Recovery |

| Lumbar herniated disc+spinal stenosis (ED)a Current case (2004) | 48/F | Prone | 36 h postoperative | Both CHs | Anti-edema drugs and serial imaging | Recovery |

CH cerebellar hemisphere, EVD external ventricular drain, Mn meningitis, ID intradural, ED extradural a Dura opened accidentally in all ED cases

All ten individuals exhibited severe headache and decreased level of consciousness in association with RCH, and the consciousness levels ranged from a state of awake, anxious, and agitated to comatose state. The two important features of our case that shares with these ten previous cases are opening of the dura and consequent loss of CSF.

Different authors have proposed several pathological mechanisms for RCH, but none has been proven scientifically. Chadduck [3] postulated that elevated blood pressure might cause an increased gradient between intravascular pressure and CSF pressure, and thus induce hemorrhage into the cerebellar parenchyma. Andrews and Koci [1] speculated that their case of cerebellar infarction resulted from transient traction, kinking, or spasm of the superior cerebellar arteries, and that hemorrhage occurred upon reperfusion. Some researchers have theorized that excessive CSF drainage per- or postoperatively could cause the cerebellum to become inferiorly dislocated, with possible tearing of the superior vermian veins [4, 13, 16]. However, work by Wang et al. [15] suggest that placement of a closed-suction drain in the epidural space does not aggravate CSF leakage. They observed no untoward effects on the cerebellum; thus, we felt that it was safe to use this type of drainage in our case.

As mentioned, peroperative patient positioning is one factor that is believed to lead to RCH after cranial surgery [4, 12]. It is known that, in patients who undergo pterional craniotomy, hyperextension of the neck and subsequent turning of the head to the side can cause relative obstruction of the ipsilateral jugular vein [12]. In our case, both the neurosurgery and anesthesiology teams took care to ensure that there was no excessive neck hyperextension intraoperatively. The above-mentioned ten patients with RCH were operated in three different positions, and the data from these cases indicate no causative relationship between patient positioning and this type of hemorrhage after spinal surgery (Table 1).

Several other factors, including arterial hypertension, anticoagulation therapy, coagulopathy, aneurysm, and arteriovenous malformations, have also been identified as possible predisposing factors for RCH [10, 13, 14]. Our patient had no history of hypertension and did not develop this problem peroperatively or postoperatively, and no arteriovenous malformation was apparent on CT angiography. None of the factors listed above is universally accepted, and none is believed to be the sole cause of RCH. The pattern of RCH observed on the CT scans after spinal surgery in our case was similar to those patterns that had been reported by other authors after supratentorial operations [2, 4, 14]. In the two cases of RCH described by Friedman et al. [4], the hemorrhage had occurred in the superior portion of the vermis and in the superior part of the cerebellar hemisphere. In our case, the hemorrhage was in both cerebellar hemispheres, just below the tentorium.

Small cerebellar hematomas can be managed medically and followed with serial imaging; however, large hematomas that cause significant mass effect in the posterior fossa may require surgical decompression [1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11]. Compression of the fourth ventricle and resultant non-communicating hydrocephalus should be managed with CSF diversion procedures [1, 5]. Decompression is necessary if there are signs and symptoms of brainstem compression due to increased intracranial pressure, and in such cases, evacuation of the hematoma should be performed immediately. Expanded suboccipital craniectomy and duraplasty are the procedures used to decompress the posterior fossa. Of the ten previously reported cases of RCH, four were managed medically with anti-edema drugs (dexamethasone), analgesics and bed rest, and the other six were managed both surgically and medically (Table 1). All four of the patients, who were treated with medical management alone, had small hematomas. After surgery, these individuals were awoke and responsive to commands only, and their neurological status did not deteriorate after the hemorrhage was detected.

The other six patients were treated with posterior fossa decompression or CSF diversion. In all of these cases, neurological status deteriorated with time after hemorrhage, changing from awake state to semicomatose or comatose state. As these reports indicate that treatment for RCH depends on the patient’s neurological status as well as the on the nature of the lesion.

In summary, based on the experience with RCH to date, it appears that this type of hemorrhage can occur after any type of spinal surgery, regardless of body positioning. The previously reported ten cases as well as our current case feature CSF loss due to the opening of the dura intraoperatively. Large-volume CSF loss intraoperatively or postoperatively may be an etiologic factor in RCH. We believe that it is important to consider the possibility of RCH in any patient who exhibits unexplained neurological deterioration after the dura mater has been opened during spinal surgery and when a large volume of CSF has been lost intraoperatively or postoperatively. Such patients should undergo immediate neuroradiological examination. Small hematomas due to RCH can be managed medically and then monitored with serial imaging, but larger lesions that cause significant mass effect in the posterior fossa must be treated surgically.

References

- 1.Andrews RT, Koci TM. Cerebellar herniation and infarction as a complication of an occult postoperative lumbar dural defect. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1312–1315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisman MH, Bederson JB, Sen CN, Germano IM, Moore F, Post KD. Intracerebral hemorrhage occuring remote from the craniotomy site. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:1114–1122. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chadduck WM. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating cervical laminectomy. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:185–189. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman JA, Ecker RD, Piepgras DG, Duke DA. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery: report of two cases and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1361–1364. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200206000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gobel F, Heidecke V, Hube R, Reichel H, Held A, Hein W. Cerebellar hemorrhage as an early complication of spinal operations. Two case reports and review of the literature. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1999;137:371–375. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalfas IH, Little JR. Postoperative hemorrhage: a survey of 4992 intracranial procedures. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:343–347. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konig A. Postoperative hemorrhage (Letter) J Neurosurg. 1997;86:916–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikawa Y, Watanabe R, Hino Y, Ishii R, Hirano K. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating cervical durotomy and revision C1-C2 fusion. Spine. 1994;19:1169–1171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199405001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morandi X, Riffaud L, Carsin-Nicol B, Guegan Y. Intracerebral hemorrhage complicating cervical “hourglass” schwannoma removal. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:150–153. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.94.1.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papanastassiou V, Kerr R, Adams C. Contralateral cerebellar hemorrhagic infarction after pterional craniotomy: report of five cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:841–852. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199610000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satake K, Matsuyama Y, Iwata H, Sato K, Kawakami N. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating resection of a cervical intramedullary tumor. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:504. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seoane E, Rhoton AL. Compression of the internal jugular vein by the transverse process of the atlas as the cause of cerebellar hemorrhage after supratentorial craniotomy. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas G, Jayaram H, Cudlip S, Powell M. Supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage secondary to intracranial CSF hypotension following spinal surgery. Spine. 2002;27:E410–E412. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toczek MT, Morrell MJ, Silverberg GA, Lowe GM. Cerebellar hemorrhage complicating temporal lobectomy. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:718–722. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.4.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80:1728–1732. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida S. Cerebellar hemorrhage after supratentorial craniotomy-report of three cases. Neurol Med Chir. 1990;30:738–743. doi: 10.2176/nmc.30.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]