Abstract

Purpose

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25-75) are not included in routine monitoring of asthma control. We observed changes in FeNO level and FEF25-75 after FeNO-based treatment with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in children with controlled asthma (CA).

Methods

We recruited 148 children with asthma (age, 8 to 16 years) who had maintained asthma control and normal forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) without control medication for ≥3 months. Patients with FeNO levels >25 ppb were allocated to the ICS-treated (FeNO-based management) or untreated group (guideline-based management). Changes in spirometric values and FeNO levels from baseline were evaluated after 6 weeks.

Results

Ninety-three patients had FeNO levels >25 ppb. These patients had lower FEF25-75% predicted values than those with FeNO levels ≤25 ppb (P<0.01). After 6 weeks, the geometric mean (GM) FeNO level in the ICS-treated group was 45% lower than the baseline value, and the mean percent increase in FEF25-75 was 18.% which was greater than that in other spirometric values. There was a negative correlation between percent changes in FEF25-75 and FeNO (r=-0.368, P=0.001). In contrast, the GM FeNO and spirometric values were not significantly different from the baseline values in the untreated group.

Conclusion

The anti-inflammatory treatment simultaneously improved the FeNO levels and FEF25-75 in CA patients when their FeNO levels were >25 ppb.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, Spirometry, Inhaled corticosteroids, Asthma, Child

Introduction

Current guideline-defined asthma control cannot be applied to the level of airway inflammation because neither symptoms nor the results of basic pulmonary function tests can reflect ongoing airway inflammation1,2). Consequently, asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients are usually considered to have controlled asthma (CA) even if they have subclinical airway inflammation. Measures of airway inflammation are thus required to identify patients with silent airway inflammation which does not manifest itself as symptoms or impaired lung function. In addition, measurement should be easy to perform, reproducible, and associated with a high degree of acceptance by patients. In this regard, the advent of FeNO measurements represents a significant advance in monitoring airway inflammation of asthmatic patients. High FeNO values above certain cut-point may indicate active eosinophilic airway inflammation and the likelihood of deterioration in asthma control3). FeNO measurements have also shown potential utility in guiding anti-inflammatory therapy in asthmatic patients4-6). However, the clinical value of FeNO measurements is questioned because FeNO levels are increased in asthma even in mild and asymptomatic conditions7,8).

Current guidelines for asthma management recommended forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) as a principle spirometric parameter to assess airflow limitation9,10). However, asthmatic subjects have air trapping in the presence of normal FEV111). Air trapping in asthmatic subjects has been demonstrated to be better correlated with forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25-75) than FEV112). In fact, impaired FEF25-75 is one of the most common abnormalities in pulmonary function in cross-sectional studies in asymptomatic patients13,14).

It remains unclear whether high FeNO or impaired FEF25-75 implies the need for anti-inflammatory treatment in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients. Therefore, it is required to observe improvement of these parameters in these patients after therapeutic intervention. In this study, to demonstrate concurrent improvement of FeNO and FEF25-75, we observed the changes of FeNO and FEF25-75 after FeNO-based treatment with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in children who maintain asthma control and normal FEV1 without controller medication.

Materials and methods

1. Patients

We recruited 153 patients 8 to 16 years of age with CA (asthma control test [ACT] or childhood asthma control test [C-ACT] score≥20) who were attending a specialist clinic at Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea, between May and July, 2010. Each patient had maintained asthma control and normal FEV1 (≥80% predicted) without controller medication for 3 months or more. All of these patients were found to be sensitized to aeroallergens and previously diagnosed to have asthma based on the documentation of airway hyperresponsiveness (methacholine PC20≤8 mg/mL) and/or reversible airflow obstruction (≥12% improvement in FEV1 in response to inhaled β2-agonist). We excluded patients who had significant pulmonary disease other than asthma or a history of gastroesophageal reflux. Thirty one non-atopic healthy controls selected after the school medical examinations as well as 20 atopic children with uncontrolled asthma (ACT or C-ACT score<20) were also recruited for spirometry and FeNO measurement. Data from both groups of children were compared with those from patients with CA. Children with uncontrolled asthma included patients referred for the first time and regularly followed-up patients with recent aggravation of asthma. All of these patients were also not receiving a regular treatment with controller medications for 3 months or more before evaluation of FeNO and lung function. The Ethics Committee of Chungbuk National University Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study (2010-12-078), and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all subjects.

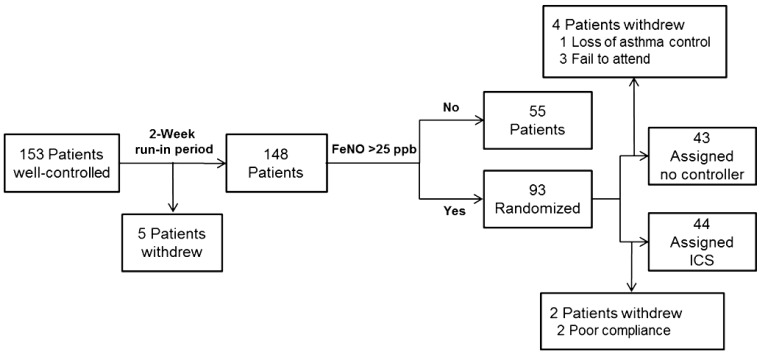

2. Study design

Trial profile is outlined in Fig. 1. After recruitment, patients with CA underwent a 2 week run-in period during which they did not receive any clinical intervention. For baseline measurements, ACT or C-ACT scores, FeNO, and spirometric values were recorded. Patients with FeNO level greater than 25 ppb were randomly allocated to one of two groups. Randomization was done by an independent individual with the method of minimization15) and was stratified by baseline FeNO. In the treated group (FeNO-based management), participants were assigned to once daily treatment with 400 µg budesonide (Obucort, Korea Otsuka Pharm, Seoul, Korea). In the untreated group (guideline-based management), participants did not receive any medication. In a treated group, adherence with treatment was assessed by asking children to return used inhalers. FeNO levels, spirometric values, and ACT or C-ACT scores of all participants were recorded 6 weeks later. FeNO levels and spirometric values were measured by skilled technicians who were unaware of the patients' randomization status.

Fig. 1.

Trial profile. FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

3. ACT and C-ACT

We used the Korean version of the ACT or C-ACT questionnaire. The ACT survey is a patient-completed questionnaire with 5 items. Each item includes 5 response options corresponding to a 5-point Likert-type rating scale (total score range, 5 to 25). The C-ACT completed by children and their parents was scored as the sum of the response codes for the 7 items. The child selects a sad to smiling face with a score from 0 to 3, on their own or with caregiver's guidance, in response to four questions of the intrusiveness of their asthma symptoms. Caregivers respond to three additional questions of the child's condition. These three questions are scored on a 5-point Likert-type rating (total score range, 0 to 27). Children and parents were encouraged to discuss their problem or doubts in completing the questionnaire. A score of 20 or more in ACT or C-ACT was considered to indicate adequately CA.

4. FeNO measurement

FeNO was measured during scheduled study visits by chemoluminescence using an online nitric oxide monitor (NIOX MINO, Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden), according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines16). The expiratory flow rate was 50 mL/sec. Exhalation times were 10 seconds with a 2-minute analysis period. Children were required to have repeated measurements (two values that agree within 5% or 3 that agree within 10%) for acceptability. Measurements were made before the performance of spirometry.

5. Spirometry

Lung function tests were performed with spirometer (Vmax, SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA) in accordance with ATS/ERS recommendations17,18). The following variables were obtained from the best of 3 reproducible forced expiratory maneuvers: forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1, FEF25-75, and FEV1/FVC ratio. Percent predicted values were calculated based on Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey19).

6. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean (95% confidence interval). FeNO was log transformed, to assume a normal distribution, and expressed as a geometric mean (GM). Baseline characteristics of high FeNO groups with CA were compared with low FeNO groups with CA, healthy control subjects, and subjects with uncontrolled asthma by using χ2, Mann-Whitney, or t-tests, as appropriate. Differences in paired data were tested with the paired t-test. Correlation coefficients between changes from baseline in FeNO and spriometric values were determined by using Pearson's correlation test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the commercially available SPSS ver. 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

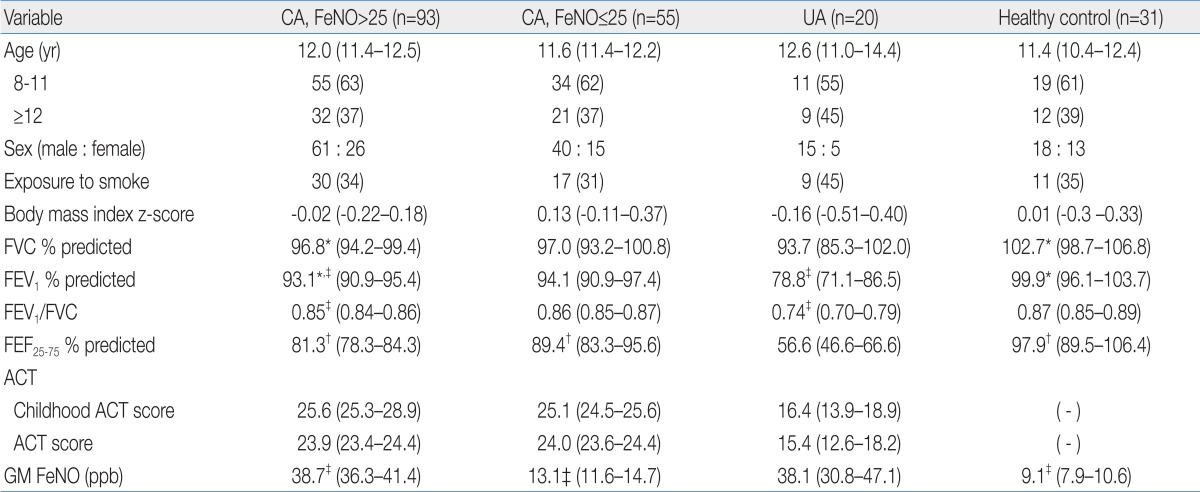

Of 153 patients with CA, 5 patients withdrew during a run-in period. Thus, FeNO was measured after a run-in period in 148 patients, 93 of them (63%) had FeNO values greater than 25 ppb. Characteristics of patients with CA who had high (>25 ppb) or low (≤25 ppb) FeNO values, patients with uncontrolled asthma, and healthy control patients are described in Table 1. There was no difference in age, sex, exposure to parental smoking, and body mass index between groups. FVC, FEV1, and FEF25-75 in patients with CA and high FeNO were lower than in healthy controls, whereas FEV1/FVC was comparable between two groups. All spirometric values except FVC were higher in patients with CA and high FeNO than patients with uncontrolled asthma. Among patients with CA, C-ACT/ACT scores and spirometric values in the high FeNO group were not significantly different from those in the low FeNO group except for FEF25-75, which was lower in the high FeNO group. C-ACT/ACT scores were significantly higher in patients with CA than those in patients with uncontrolled asthma. GM FeNO in patients with CA and high FeNO was significantly higher than in healthy controls or patients with CA and low FeNO. In contrast, there was no difference in GM FeNO between patients with CA and high FeNO and patients with uncontrolled asthma.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for Patients with Asthma and Healthy Controls

Values are presented as mean (95% confidence interval) or number (%).

CA, controlled asthma; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; UA, uncontrolled asthma; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity; ACT, asthma control test; GM, geometric mean.

CA, FeNO>25 vs. other groups; *P<0.05, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001.

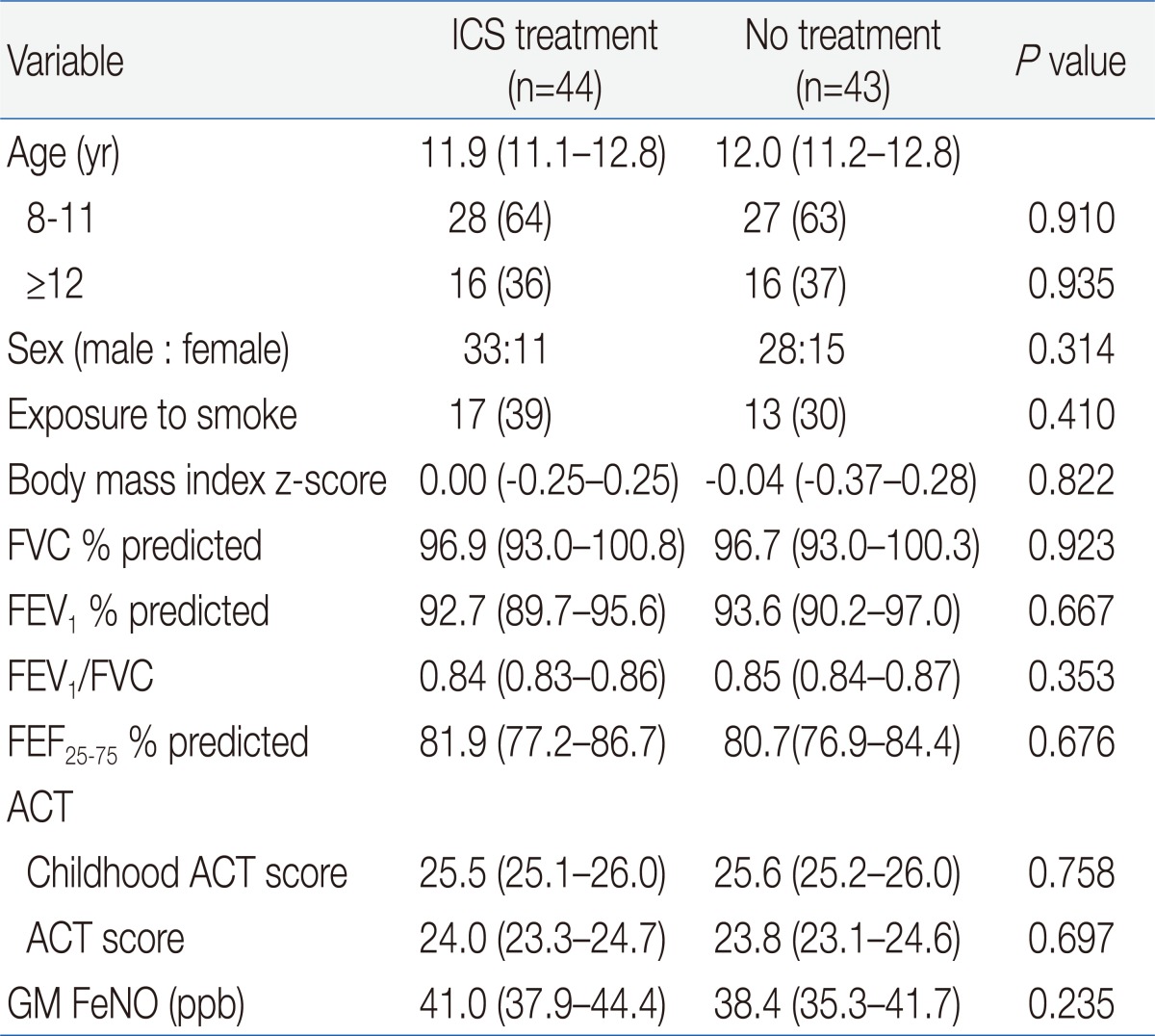

Of 93 patients with CA and high FeNO, 46 patients were allocated to the treated group and 47 to the untreated groups. Two patients withdrew from the treated group because of poor compliance (Fig. 1). In the untreated group, 1 patient withdrew because of poorly CA and a further 3 patients withdrew because of nonattendance at a scheduled visit. In the end, 44 patients in the treated group and 43 patients in the untreated group completed the study. Both groups were matched at baseline for demographic and clinical features (Table 2). In addition, there was no significant difference at baseline in GM FeNO and spirometric values between two groups.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Patients

Values are presented as mean (95% confidence interval) or number (%).

ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity; ACT, asthma control test; GM, geometric mean; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

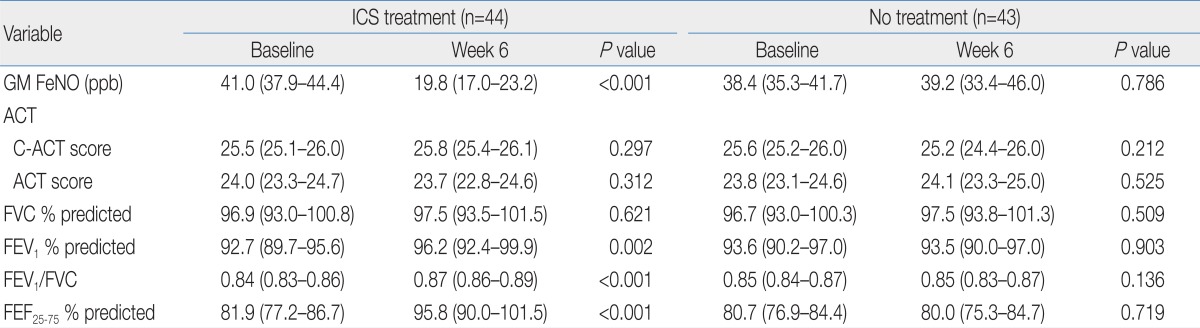

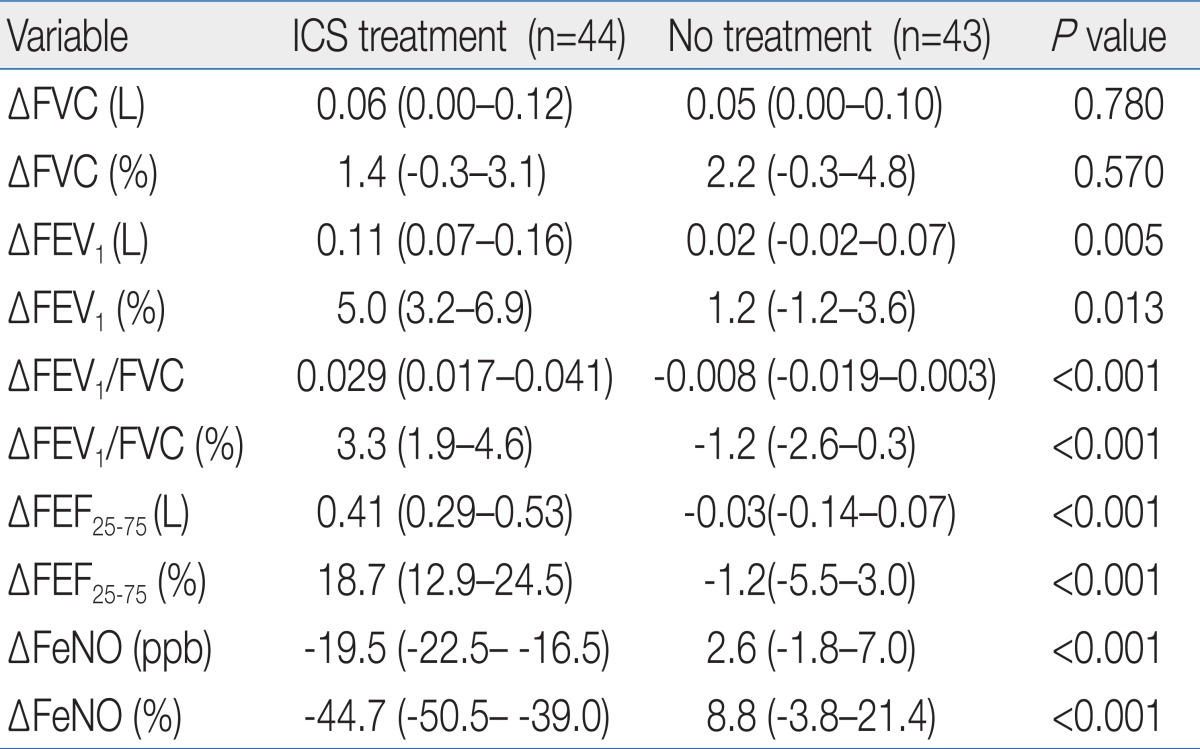

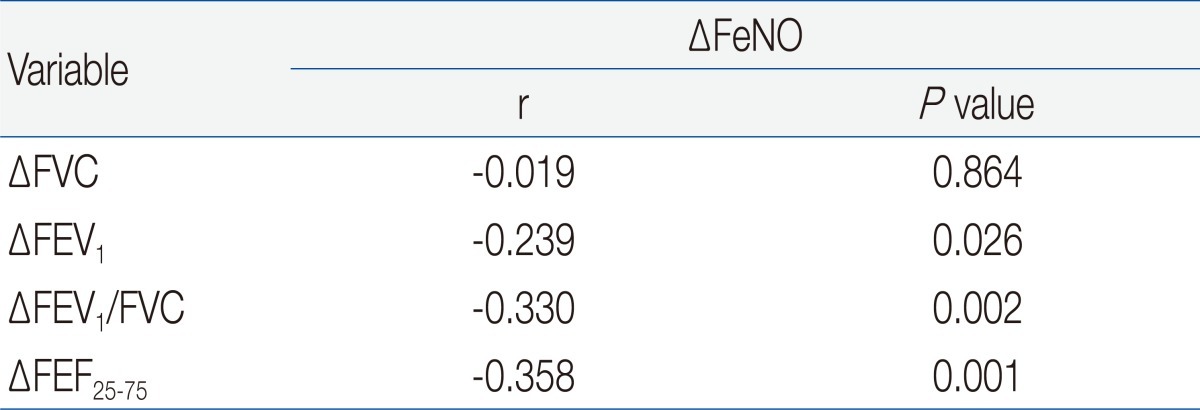

The changes in ACT/C-ACT scores were not observed after 6 weeks in both groups (Table 3). However, GM FeNO in the treated group was significantly lower compared with a baseline value after 6 weeks. In addition, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and FEF25-75 in this group were significantly increased from baseline. In contrast, GM FeNO and spirometric values at week 6 in the untreated group were not significantly different from baseline values. With the exception of FVC, the absolute and percent changes of GM FeNO and spirometric values were greater in the treated group compared with the untreated group (Table 4). In the treated group, the mean absolute increase in FEF25-75 (ΔFEF25-75) was much greater than that of FEV1 (ΔFEV1). In addition, mean percent changes in FeNO and FEF25-75 were more prominent than those in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. Although spirometric values were not negatively correlated with FeNO levels in our study population, there were negative correlations between the percent changes in FeNO and spirometric values except for FVC (Table 5). The strongest relationship was observed between the percent changes in FeNO and FEF25-75.

Table 3.

FeNO, Spirometric Values, and ACT/C-ACT Scores in Patients with and without ICS Treatment

Values are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ACT, asthma control test; C-ACT, childhood asthma control test; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; GM, geometric mean; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity.

Table 4.

Absolute and Percent Changes in Spirometric Values and FeNO Levels from the Baseline Values

Values are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity.

Table 5.

Correlations between the Percent Changes from the Baseline FeNO levels and Spirometric Values in Patients Treated with ICS

FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FEF25-75, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity.

Discussion

We focused on patients requiring no controller medication to maintain asthma control. As determined in previous studies20,21), ACT or C-ACT scores of 20 or more in these patients indicate good asthma control of symptoms. In addition, FEV1 greater than 80% of predicted implies low possibility of airflow limitation in this group of patients. However, monitoring of asthma control based on symptoms and normal FEV1 might result in under-treatment because persistent airway inflammation does not necessarily manifest itself as symptoms or lung malfunction2,22). FeNO measurements for monitoring of silent airway inflammation were thus required and might potentially allow for better targeting and monitoring of anti-inflammatory treatment23). Previous studies regarding asymptomatic subjects who had well-documented atopic asthma in the past showed that levels of FeNO in these patients were elevated and even similar to those found in subjects with current asthma24,25). We also found that a substantial proportion of patients with CA had comparable levels of FeNO to patients with uncontrolled asthma. These findings may suggest active eosinophilic airway inflammation and the likelihood of deterioration in asthma control even if the patient is asymptomatic26).

Persisting abnormal lung function in asymptomatic patients with asthma has been reported in previous studies13,14), implying a weak relationship between symptoms and lung function. In our study, all spirometry values of patients with CA were greater than 80% of predicted and significantly higher than those in patients with uncontrolled asthma. However, lung function of these patients seemed to be impaired because spirometric values in these patients were lower than those in normal healthy controls. The increase of spirometric values after treatment with ICS strengthens the evidence base for the abnormal lung function in these patients. In addition, the ICS-induced changes in FeNO were found to be correlated with those in spirometric values. These findings suggest that the improvement of airflow limitation may result from the reduction of airway inflammation.

In this current study, a difference in FEF25-75 between patients with CA and normal control subjects was more prominent than other spirometric values. Among patients with CA, FEF25-75 was an only spirometric value which was significantly lower in a high FeNO group than in a low FeNO group. Furthermore, the percent changes of FEF25-75 were more prominent after ICS treatment compared with those in other spirometry values. Therefore, FEF25-75 appears to be more sensitive in detecting a ventilation defect of patients with CA than other spirometric values which were minimally impaired in these patients. Moreover, despite that FEF25-75 itself was not negatively correlated with FeNO in our study population, the increase of FEF25-75 coincided with the reduction of FeNO after treatment with ICS as reflected by good correlation between the changes of two parameters. This finding suggests that serial combined measurements of FeNO and FEF25-75, rather than a snapshot measurement, may be more useful in monitoring asthma control and may play a role in the early detection of asthma progression. In addition, concurrent improvement of FEF25-75 and FeNO by anti-inflammatory treatment raises the possibility of subclinical airway inflammation in patients with CA.

Because previous clinical trials reported only equivocal benefits of adding measurements of FeNO to usual clinical guideline management, it has not been determined that FeNO-based management is beneficial in routine clinical practice4-6,27). Our data raise a possibility that FeNO measurement may be useful for the early detection of a progressive illness at a time point when interventions would be likely to change its natural history. However, we were not able to determine whether the improvement of FeNO or FEF25-75 predicted the future clinical course, since the effect of intervention may occur over a longer time course. Therefore, future longitudinal studies should assess the possible benefits of FeNO-based anti-inflammatory treatment during the asymptomatic phase.

The weakness of this study is that FeNO cut point of 25 ppb might lead to inclusion of patients who did not have substantial airway inflammation because a number of nonasthmatic factors may occasionally give rise to increased FeNO levels even in healthy individuals28,29). We chose this cut point on the basis of an earlier work identifying it as an indicator for the presence of a raised sputum eosinophil count30), a measure that has been shown to be useful in monitoring asthma31). In addition, this cut point was reported to be higher than those in healthy children32) and also definitely higher than that in our nonatopic nonasthmatic control group. Thus, our cut point is thought to be optimal for selecting patients with relatively higher probability of airway inflammation. Another weakness of this study is that we did not evaluate the influence of allergic rhinitis. Contamination of the exhaled air by NO-rich air from the nasal cavity is unlikely, as the soft palate elevates when expiration is performed against a resistance33,34). This suggests that high FeNO in patients with allergic rhinitis results from an increased production of NO in the lower airways. Thus, it is certainly plausible that the influence of rhinitis on the FeNO levels may be limited.

In summary, we showed that high FeNO as well as low FEF25-75 were detected in a substantial proportion of patients who maintain asthma control and normal FEV1 without controller medication. FeNO-based anti-inflammatory treatment in these patients resulted in concurrent improvement of FeNO and FEF25-75. Thus, combined measurements of FeNO and FEF25-75 may be useful for the early detection of a progressive illness requiring anti-inflammatory treatment.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the research grant of the Chungbuk National University in 2010.

References

- 1.Crimi E, Spanevello A, Neri M, Ind PW, Rossi GA, Brusasco V. Dissociation between airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:4–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9703002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundback B, Dahl R. Assessment of asthma control and its impact on optimal treatment strategy. Allergy. 2007;62:611–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DR, Pijnenburg MW, Smith AD, De Jongste JC. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements: clinical application and interpretation. Thorax. 2006;61:817–827. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AD, Cowan JO, Brassett KP, Herbison GP, Taylor DR. Use of exhaled nitric oxide measurements to guide treatment in chronic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2163–2173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Green RH, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, et al. The use of exhaled nitric oxide to guide asthma management: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:231–237. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1427OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pijnenburg MW, Bakker EM, Hop WC, De Jongste JC. Titrating steroids on exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:831–836. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-458OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alving K, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JM. Increased amount of nitric oxide in exhaled air of asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:1368–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Exhaled markers of pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1693–1722. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2009041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [Internet] Bethesda: NHLBI Health Information Center; c2012. [cited 2012 Jul 20]. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Full report 2007. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [Internet] [place unknown]: Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA); c2011. [cited 2012 Jan 4]. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention--updated 2011. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/uploads/users/files/GINA_Report2011_May4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samee S, Altes T, Powers P, de Lange EE, Knight-Scott J, Rakes G, et al. Imaging the lungs in asthmatic patients by using hyperpolarized helium-3 magnetic resonance: assessment of response to methacholine and exercise challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1205–1211. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lange EE, Altes TA, Patrie JT, Gaare JD, Knake JJ, Mugler JP, 3rd, et al. Evaluation of asthma with hyperpolarized helium-3 MRI: correlation with clinical severity and spirometry. Chest. 2006;130:1055–1062. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Brochu A. Persistence of airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness in subjects with asthma remission. Chest. 1994;105:1024–1031. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.4.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson AC. Persisting airway obstruction in asymptomatic children with asthma with normal peak expiratory flow rates. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;82:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation by minimisation. BMJ. 2005;330:843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7495.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:511–522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, et al. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu AH, Zeiger R, Sorkness C, Mahr T, Ostrom N, Burgess S, et al. Development and cross-sectional validation of the Childhood Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scichilone N, Battaglia S, Olivieri D, Bellia V. The role of small airways in monitoring the response to asthma treatment: what is beyond FEV1? Allergy. 2009;64:1563–1569. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pijnenburg MW, De Jongste JC. Exhaled nitric oxide in childhood asthma: a review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:246–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horvath I, Barnes PJ. Exhaled monoxides in asymptomatic atopic subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1276–1280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Den Toorn LM, Prins JB, Overbeek SE, Hoogsteden HC, de Jongste JC. Adolescents in clinical remission of atopic asthma have elevated exhaled nitric oxide levels and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3 Pt 1):953–957. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9909033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, et al. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:602–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szefler SJ, Mitchell H, Sorkness CA, Gergen PJ, O'Connor GT, Morgan WJ, et al. Management of asthma based on exhaled nitric oxide in addition to guideline-based treatment for inner-city adolescents and young adults: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61448-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olin AC, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Lissner L, Bake B, Toren K. Height, age, and atopy are associated with fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in a large adult general population sample. Chest. 2006;130:1319–1325. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kharitonov SA, Yates D, Barnes PJ. Increased nitric oxide in exhaled air of normal human subjects with upper respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:295–297. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08020295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry MA, Shaw DE, Green RH, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. The use of exhaled nitric oxide concentration to identify eosinophilic airway inflammation: an observational study in adults with asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1175–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayaram L, Pizzichini MM, Cook RJ, Boulet LP, Lemiere C, Pizzichini E, et al. Determining asthma treatment by monitoring sputum cell counts: effect on exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:483–494. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00137704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchvald F, Baraldi E, Carraro S, Gaston B, De Jongste J, Pijnenburg MW, et al. Measurements of exhaled nitric oxide in healthy subjects age 4 to 17 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1130–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharitonov SA, Chung KF, Evans D, O'Connor BJ, Barnes PJ. Increased exhaled nitric oxide in asthma is mainly derived from the lower respiratory tract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(6 Pt 1):1773–1780. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silkoff PE, McClean PA, Slutsky AS, Furlott HG, Hoffstein E, Wakita S, et al. Marked flow-dependence of exhaled nitric oxide using a new technique to exclude nasal nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:260–267. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]