Abstract

Hybrid incompatibility (HI) genes are frequently observed to be rapidly evolving under selection. This observation has led to the attractive conjecture that selection-derived protein-sequence divergence is culpable for incompatibilities in hybrids. The Drosophila simulans HI gene Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) is an intriguing case, because despite having experienced rapid sequence evolution, its HI properties are a shared function inherited from the ancestral state. Using an unusual D. simulans Lhr hybrid rescue allele, Lhr2, we here identify a conserved stretch of 10 amino acids in the C terminus of LHR that is critical for causing hybrid incompatibility. Altering these 10 amino acids weakens or abolishes the ability of Lhr to suppress the hybrid rescue alleles Lhr1 or Hmr1, respectively. Besides single-amino-acid substitutions, Lhr orthologs differ by a 16-aa indel polymorphism, with the ancestral deletion state fixed in D. melanogaster and the derived insertion state at very high frequency in D. simulans. Lhr2 is a rare D. simulans allele that has the ancestral deletion state of the 16-aa polymorphism. Through a series of transgenic constructs we demonstrate that the ancestral deletion state contributes to the rescue activity of Lhr2. This indel is thus a polymorphism that can affect the HI function of Lhr.

Keywords: hybrid incompatibility, indel polymorphism

WHAT evolutionary forces drive speciation? A significant step toward answering this question has been the identification of hybrid incompatibility (HI) genes, that is, genes with “incompatible substitutions” that cause breakdown in interspecific hybrids. The next challenge is describing the evolutionary basis for the origin of such incompatible substitutions. The classic Dobzhansky–Muller (D–M) model elegantly explains how substitutions incompatible only in an interspecific context can evolve; however, it is agnostic on the nature of the intraspecific evolutionary forces that cause them (Presgraves 2010; Maheshwari and Barbash 2011). The model is equally consistent with incompatible substitutions evolving as functionally neutral mutations drifting to fixation or as functionally advantageous mutations being driven to fixation by natural selection.

It is therefore particularly intriguing that so many HI genes show high rates of sequence divergence driven by positive selection. If this divergence corresponds to the incompatible substitutions then there is a direct link between the phenotype under selection and HI. This is very likely for the hybrid sterility gene OdsH, where the signature of selection is concentrated within the DNA-binding homeodomain, because functional analysis of OdsH orthologs has implicated divergent DNA-binding activity in hybrid incompatibility (Ting et al. 1998; Bayes and Malik 2009). However, such a direct link between sequence divergence and function remains to be established for other rapidly evolving HI genes.

The HI gene Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) poses an interesting paradox. Lhr causes F1 hybrid male lethality in crosses between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans (Watanabe 1979; Brideau et al. 2006). The classic D–M model describes HI as the negative ectopic interaction between two derived loci, thus setting up the expectation that selection-driven divergence of Lhr led to incompatible substitutions in one of the hybridizing lineages. Surprisingly, however in transgenic assays, Lhr orthologs from both hybridizing species cause hybrid dysfunction (Brideau and Barbash 2011; Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). This argues against the expectation that the hybrid lethal activity of Lhr is solely the outcome of selection-driven substitutions in its protein coding sequence (CDS) specific to D. simulans. Moreover, our recent results argue that the divergent hybrid lethal activities of Lhr orthologs can be largely attributed to their asymmetric expression in the hybrid background (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). The D. simulans Lhr allele is expressed twofold higher than the D. melanogaster ortholog in the F1 hybrid. But it is still an open question whether divergence of the CDS might also be contributing to the differential hybrid lethal effects of Lhr.

Lhr orthologs have ∼50 fixed differences between D. melanogaster and D. simulans scattered throughout a protein sequence of only ∼330 residues. Additionally, Lhr from each of the sibling species D. simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia has a 16-amino acid (aa) insertion relative to the D. melanogaster ortholog. The insertion is absent in outgroup species and is therefore identified as a derived state, specific to the common ancestor of the sibling species. This 16-aa insertion is also interesting because it may affect the structure of a predicted leucine zipper in the LHR protein and had been proposed as a candidate for mediating functional differences between the D. melanogaster and D. simulans Lhr orthologs (Brideau et al, 2006).

The discovery of D. simulans Lhr2 motivated us to further explore the effect, if any, of this 16-aa region on the hybrid lethal activity of Lhr orthologs. Lhr2 partially suppresses hybrid male lethality, strongly suggesting that it is a loss-of-function allele. Interestingly, Lhr2 lacks the 16-aa insertion found in most other D. simulans Lhr alleles. However, the Lhr2 allele also has a complex deletion in its C terminus within a sequence of high conservation (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Furthermore, it was not tested whether Lhr2 is wild type in expression level, which is critical because Lhr1 is strongly reduced in expression (Brideau et al. 2006). Thus, even if the hybrid rescue property of the D. simulans Lhr2 strain is a function of the unusual CDS of the Lhr2 allele, it is unclear whether one or both of the aforementioned two major mutations are responsible for its hybrid rescue activity.

A population survey revealed that the ancestral noninsertion form is segregating at a very low frequency in some D. simulans populations (Nolte et al. 2008). Nolte et al. (2008) tested two D. simulans strains in hybrid crosses that carried Lhr alleles lacking the 16-aa insertion but wild type at the C terminus. Neither of these strains produced viable hybrid sons, leading them to conclude that the hybrid rescue property of the D. simulans Lhr2 strain is not caused by the ancestral noninsertion form of the 16-aa region, leaving the complex C-terminal mutation as the most likely candidate. However, whether the presence or absence of this 16-aa region makes any contribution either to functional differences between mel-Lhr and sim-Lhr, or to the hybrid rescue properties of Lhr2, remains untested. Here we describe a series of transgenic assays to address these questions.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks and culturing

All crosses were done at room temperature or at 18° where explicitly stated. At least two replicates were done for each cross. Each interspecific cross was initiated with ∼15–20 one-day-old D. melanogaster virgin females and ∼30–40 three- to 4-day-old sibling-species males. Genetic markers, deficiencies, and balancer chromosomes are described on FlyBase (McQuilton et al. 2012).

Nomenclature

The abbreviations mel-Lhr and sim-Lhr refer to the Lhr orthologs from D. melanogaster and D. simulans, respectively. We refer generically to the 16-aa region that is present in sim-Lhr and absent in mel-Lhr as the “16-aa indel.” Because it is a derived insertion in the D. simulans lineage but absent in the sim-Lhr2 allele, we refer to it as the “16-aa deletion” in sim-Lhr2 and in mel-Lhr and as the “16-aa insertion” in sim-Lhr.

DNA constructs

PCR primers are listed in Table S1. To generate constructs for transgenic experiments (Figure 1), first the wild-type Lhr CDS in p{sim-Lhr} from (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012) was replaced by the Lhr2 CDS using a three-piece fusion PCR strategy. The first and last PCR products, containing upstream and downstream genomic regions, were amplified using p{sim-Lhr} as the template, with primer pairs 691/938 and 941/664, respectively. The central PCR product containing the Lhr2 CDS was amplified from D. simulans Lhr2 genomic DNA, with primer pair 939/940. The three overlapping PCR products were then used as templates for the fusion PCR using primers 691/664, cloned into the pCR-BluntII vector to create the plasmid p{sim-Lhr2}, and sequenced completely.

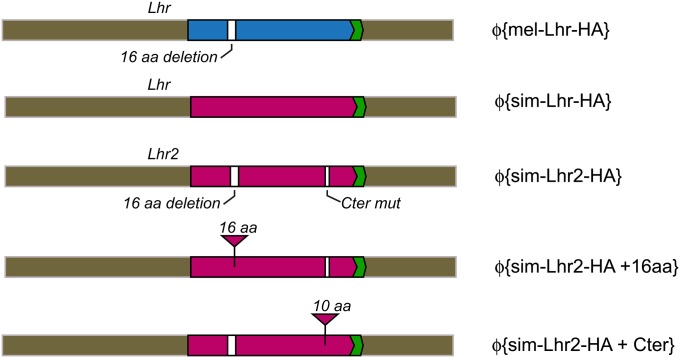

Figure 1 .

Schematic of the Lhr2 constructs. The mel-Lhr-HA and sim-Lhr-HA constructs are described in (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). All other constructs contain the full sim-Lhr2 coding sequences fused to the HA epitope tag (green) with the UTRs and genomic DNA from the D. simulans w501 strain. White boxes represent the 16-aa deletion and C-terminal mutations. Triangles represent replacement of Lhr2 CDS with sequence from wild-type D. simulans Lhr.

A triple-HA tag in frame with the C terminus of Lhr2 CDS was synthesized using a two-piece fusion PCR strategy. Two overlapping PCR products were amplified using p{sim-Lhr2} as the template, with primer pairs 882/728 and 729/664. Fusion PCR was then performed using these products as the templates with primers 882/664, and the resulting product was TOPO cloned into the pCR-BluntII vector. This intermediate construct was digested with SacII and ApaI and the fragment released was subcloned into p{simLhr2}, generating p{sim-Lhr2-HA}. The full insert was sequenced completely and subcloned into the multiple cloning site of pCasper4\attB using NotI and KpnI restriction enzymes.

To synthesize the construct p{sim-Lhr2-HA + 16aa}, the 16-aa insertion was inserted into the Lhr2 CDS using a two-piece fusion PCR strategy. The two overlapping PCR products were amplified using p{sim-Lhr2-HA} as the template, with primer pairs 691/945 and 946/664. These fragments were used as templates for the fusion PCR with primers 691/664, and the gel-purified product was TOPO cloned into the pCR-BluntII vector and sequenced completely. The insert was then subcloned into pCasper4\attB exactly as in p{sim-Lhr2-HA}. The construction of p{sim-Lhr2-HA +Cter}, where the complex mutation in the C terminal mutation in Lhr2 CDS was replaced by 10 residues of wild-type D. simulans Lhr sequence, was done as above using primer pairs 691/942 and 943/664.

For yeast two-hybrid experiments, the Lhr2 CDS was amplified from genomic DNA using primer pair 404/405 and cloned into pENTR-DTOPO (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and verified by sequencing. The entry vector was recombined with the destination vectors in a standard LR Clonase (Invitrogen)-mediated reaction. The destination vectors used were pGADT7-AD and pGBKT7-DNA-BD (K. Ravi Ram, A. Garfinkel, and M. F. Wolfner, personal communication).

Transgenic fly lines

ΦC31-mediated transformants of D. melanogaster were performed by Genetic Services. The integration site used was M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH-86Fb at cytological position 86Fb (Bischof et al. 2007). Site specificity of integrations were tested using the PCR assays described in Maheshwari and Barbash (2012).

Recombination mapping of the D. simulans Lhr2 rescue activity

The D. simulans Lhr2 rescue strain was outcrossed to the nonrescuing D. simulans v strain. From this, seven independent recombination lines were established by backcrossing 8–10 F1 daughters to 8–10 males from the D. simulans v strain. Sons from this cross were used to set up three hybrid crosses. Each hybrid cross was set up with ∼30 recombinant sons, aged for 3 days, and twenty 0- to 1-day-old virgin D. melanogaster w1118 females. Individual viable F1 hybrid sons, which by definition inherit the mutation responsible for rescue, were PCR genotyped for their Lhr alleles. To determine whether hybrid sons inherited the wild-type Lhr or the Lhr2 allele from the D. simulans father, we used primer pairs 409/410 to PCR across the 16-aa indel. If sons inherit wild-type D. simulans Lhr we expect to see two bands, the smaller band corresponding to the ancestral state in D. melanogaster Lhr and the larger size corresponding to the insertion in wild-type D. simulans Lhr; however, if they inherit the Lhr2 alelle, we expect to see only one band corresponding to the ancestral state.

RT–PCR, immunofluorescence, and yeast two hybrid

RT–PCR and immunofluorescence were performed as previously described (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as in Brideau and Barbash (2011).

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

We examined Lhr sequences from a recent large-scale resequencing of D. melanogaster populations and found all 158 strains contain the 16-aa deletion (Mackay et al. 2012). We also searched the short-read archive from this project, using as the query a 100-bp sequence from mel-Lhr flanking the site of the 16-aa indel. All 26 traces from 454 sequencing fully matched the query. In combination with our previous polymorphism sampling of mel-Lhr (Brideau et al. 2006), we conclude that D. melanogaster is fixed for the deletion form of the 16-aa indel. The phylogenetic tree was built by MEGA 5.05 using the maximum parsimony method (Tamura et al. 2011). The Lhr alleles used for the analysis are published in Brideau et al. (2006). For phylogenetic analysis the region corresponding to the C-terminal mutation in Lhr2 was excluded from the alignment.

Results

D. simulans Lhr2 is mutant in its coding sequence

A cross between wild-type D. melanogaster females and D. simulans males produces only sterile daughters and no sons. The genetic basis of male lethality appears to be fixed between the two species, as crosses between many different wild-type strains fail to produce hybrid sons (Sturtevant 1920; Lachaise et al. 1986). The only two exceptions are strains with mutations in D. melanogaster Hmr or D. simulans Lhr (Watanabe 1979; Hutter and Ashburner 1987).

Although we and others implicitly assumed in previous analyses that rescue in the D. simulans Lhr2 strain is due to its unusual Lhr allele, this point has not been established (Brideau et al. 2006; Nolte et al. 2008). We therefore first did a crude mapping experiment to test whether the hybrid rescue function is associated with the Lhr2 locus. We outcrossed D. simulans Lhr2 to wild-type D. simulans and tested for linkage between the Lhr2 locus and hybrid rescue. We genotyped by PCR 48 viable hybrid sons, which by definition have inherited the rescue locus, and found that all of them also inherited the Lhr2 allele from the D. simulans parent. This pattern of cosegregation supports the hypothesis that the Lhr2 allele is responsible for suppressing hybrid male lethality instead of an unrelated mutation segregating in the same genetic background.

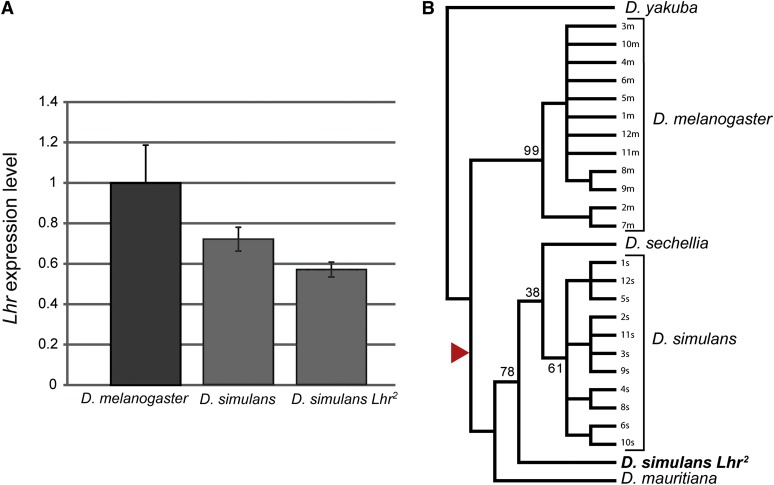

We next sequenced 4 kb of genomic DNA spanning the Lhr2 locus and found only several SNPs but no insertions, deletions, or rearrangements in its noncoding regions, suggesting that the Lhr2 allele is unlikely to be mutant in its expression. Using quantitative RT–PCR we determined that Lhr expression in D. simulans Lhr2 is not significantly different from wild type (t test, P = 0.2) (Figure 2A), demonstrating that the hybrid rescue property of D. simulans Lhr2 is different from the original rescue allele Lhr1, which is an expression mutant having nearly undetectable levels of Lhr. The Lhr2 CDS is unusual in two respects (Figure 1, Figure S1). First, Lhr2 lacks the 16-aa insertion that is present in frequencies near fixation in other sim-Lhr alleles. Second, Lhr2 has a complex mutation in a conserved sequence near its C terminus, which includes a 12-bp in-frame deletion and nonsynonymous mutations causing unique substitutions in 6 adjacent amino acids.

Figure 2 .

The Lhr2 allele is not an expression mutant or a D. melanogaster introgression. (A) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis comparing Lhr expression in D. simulans Lhr2 with D. melanogaster w1118 and D. simulans v strains, both of which are Lhr+. RNA was isolated from 6- to 10-hr-old embryos. Lhr abundance was measured relative to rpl32. Expression levels were normalized by setting D. melanogaster w1118 strain to 1. Error bars represent standard error among biological replicates, n ≥ 3. (B) Evolutionary history of Lhr2 in the melanogaster subgroup was inferred using the maximum parsimony method. Arrowhead indicates the branch on which the 16-aa insertion originated. Percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Bootstrap values are not shown for the terminal nodes within the D. melanogaster and D. simulans clades.

Considering that the D. simulans Lhr2 allele contains the melanogaster-like ancestral state at the 16-aa indel, it raised the possibility that Lhr2 is a recent introgression of D. melanogaster Lhr into D. simulans. This was rejected, however, by phylogenetic analysis that firmly groups Lhr2 with alleles from the sibling species (Figure 2B). Interestingly, Lhr2 appears to be a relatively old allele that clusters separately from other sim-Lhr alleles.

To test conclusively whether the coding sequence of the Lhr2 allele is defective for hybrid lethal activity, we used a transgenic assay to compare it with wild-type sim-Lhr. We used the ΦC31 site-specific integration system to generate a D. melanogaster strain carrying a D. simulans Lhr2 transgene at the attP86Fb site on the third chromosome (Figure 1). The Lhr2 CDS was C-terminally tagged with HA and placed under the control of wild-type D. simulans regulatory sequences (from strain w501), to generate the Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} construct.

Hybrid lethal activity was assayed using the D. simulans Lhr1 complementation test (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). D. melanogaster mothers heterozygous for an experimental or control transgene were crossed to D. simulans Lhr1 fathers, Lhr1 being a loss-of-function mutation that acts as a dominant suppressor of HI. If the transgene has hybrid lethal activity, it is expected to suppress rescue by the Lhr1 mutation. In the control cross with Φ{sim-Lhr-HA} no hybrid sons inheriting the transgene were recovered (Table 1, cross 1). This full suppression of rescue is consistent with our previous results (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). In contrast, Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} only partially suppressed rescue, with viability in the range of 35–40% relative to the control class (Table 1, cross 2). This assay demonstrates that the Lhr2 CDS has significantly reduced ability to cause HI but it is not a null allele. This conclusion is consistent with the observation that D. simulans Lhr1 rescues more strongly than D. simulans Lhr2. When crossed to D. melanogaster w1118 at room temperature, the viability of hybrid males with D. simulans Lhr1 is ∼73% relative to hybrid females (51 F1 males and 70 F1 females), while with D. simulans Lhr2, it is ∼49% (107 F1 males and 219 F1 females). Lower levels of rescue with Lhr2 compared to Lhr1 were also observed in a previous study (Barbash 2010).

Table 1 . Testing the two major mutations in Lhr2 for suppression of hybrid rescue by D. simulans Lhr1.

| No. of hybrid males | Relative viability of Φ{ } males (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross | Transgenic construct | No. of hybrid females | Genotype 1 +/Lhr1; +/+ | Genotype 2 +/Lhr1; Φ{ }/+ | |

| 1 | Φ{sim-Lhr-HA} | 135 | 74 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} | 494 | 226 | 80 | 35.4 |

| 308 | 185 | 75 | 40.54 | ||

| 3 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA+Cter} | 269 | 175 | 0 | 0 |

| 187 | 104 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA+16aa} | 337 | 178 | 28 | 15.73 |

| 224 | 164 | 26 | 15.85 | ||

Crosses were between D. melanogaster females heterozygous for the different transgenes (genotype w; Φ{ }/+) and D. simulans Lhr1 males. The transgenes carried a copy of the w+ gene so the hybrid sons inheriting the transgene, +/Lhr1; Φ{ }/+ (genotype 2) were distinguished from their +/Lhr1; +/+ siblings (genotype 1) by their eye color. All crosses were carried out at room temperature. Relative viability is the ratio of the number of hybrid sons inheriting the transgene (genotype 2) compared to the control class (genotype 1).

Assaying the function of the two major structural mutations in Lhr2

To individually test the contribution of the complex C-terminal mutation and the 16-aa deletion to hybrid lethal activity, each was individually replaced in sim-Lhr2-HA with wild-type sequence to generate Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+Cter} and Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+16aa}, respectively (Figure 1). Initial experiments suggested that the presence or absence of the C-terminal mutation has a much more significant impact on Lhr function compared to the 16-aa indel. We therefore compared them to different references in our genetic assays. For Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+Cter}, where we reverted the C-terminal mutation to the wild-type sequence, we compared its activity to the wild-type Φ{sim-Lhr-HA} control and found that it also fully suppresses rescue (Table 1, cross 3). This result demonstrates that the conserved C-terminal region is essential for wild-type Lhr function. Because Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+Cter} contains the ancestral deletion state of the 16-aa indel, this result also demonstrates that the presence or absence of the 16-aa indel region in an otherwise wild-type sim-Lhr allele does not affect the ability of sim-Lhr to suppress hybrid rescue by Lhr1.

For Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+16aa}, where we added the 16-aa insertion to the Lhr2 allele, a comparison to the construct Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} tests whether the 16-aa deletion has any functional effect in the background of an allele that is partially impaired because it carries the C-terminal deletion. In our Lhr1 complementation assay, we detected a significant difference in viability between the two genotypes of hybrid males [Table 1, cross 2 vs. 4, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (FET), P = 0.000]. The relative viability of hybrid sons inheriting Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+16aa} was reduced to ∼16% compared to ∼35–41% for Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA}. This demonstrates that having the ancestral deletion state significantly contributes to the hybrid rescue activity of Lhr2. This result thus shows that the polymorphic 16-aa indel does affect Lhr function, at least in the presence of the second C-terminal mutation.

To further explore the functional effects of the 16-aa indel, we turned to a more sensitive genetic assay for Lhr function involving its interacting partner Hmr. We have previously shown that in the background of the hypomorphic Hmr1 mutation, Lhr orthologs exhibit significantly different degrees of hybrid lethality (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). We therefore introduced each of our Lhr2 transgenes into an Hmr1 mutant background and tested the effect of the transgenes on hybrid male viability in crosses to D. mauritiana (Table 2). D. mauritiana was chosen as the male parent because in interspecific crosses between D. melanogaster females and sibling species males, D. mauritiana hybrids show the highest viability (Hutter and Ashburner 1987). The crosses were also done at both room temperature and 18° because hybrid viability is temperature dependent, with viability increasing at lower temperatures (Hutter and Ashburner 1987). Crosses with the wild-type Lhr transgenes recapitulated our previous experiments (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012): Hmr1 hybrid sons carrying sim-Lhr-HA were essentially inviable at room temperature, while hybrid sons inheriting mel-Lhr-HA had 32–44% viability (Table 2, crosses 1 and 2).

Table 2 . Testing the two major mutations in Lhr2 for suppression of hybrid rescue by D. melanogaster Hmr1.

| No. of hybrid males | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic construct | Temp. | No. of hybrid females | Genotype 1 Hmr1/Y; +/+ | Genotype 2 Hmr1/Y; φ{ }/+ | Relative viability of φ{ } males (%) | |

| 1 | Φ{mel-Lhr-HA} | RT | 446 | 78 | 25 | 32.1 |

| RT | 324 | 67 | 30 | 44.8 | ||

| 18° | 462 | 184 | 127 | 69.0 | ||

| 18° | 689 | 265 | 140 | 52.8 | ||

| 2 | Φ{sim-Lhr-HA} | RT | 305 | 55 | 1 | 1.8 |

| RT | 180 | 35 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| 18° | 692 | 283 | 90 | 31.8 | ||

| 18° | 504 | 198 | 111 | 56.1 | ||

| 3 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} | RT | 354 | 79 | 114 | 144.3 |

| RT | 361 | 80 | 111 | 138.8 | ||

| 18° | 782 | 264 | 283 | 107.2 | ||

| 18° | 742 | 253 | 250 | 98.8 | ||

| 4 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA+Cter} | RT | 226 | 47 | 1 | 2.1 |

| RT | 382 | 59 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| 18° | 561 | 236 | 106 | 44.9 | ||

| 18° | 393 | 197 | 74 | 37.6 | ||

| 5 | Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA+16aa } | RT | 86 | 32 | 34 | 106.3 |

| RT | 182 | 52 | 57 | 109.6 | ||

| 18° | 538 | 253 | 214 | 84.6 | ||

| 18° | 373 | 191 | 155 | 81.2 | ||

The different Lhr transgenes were tested for interaction with an Hmr hypomorphic allele, Hmr1. D. melanogaster w Hmr1 v; Φ{transgene, w+}/+ females were mated to D. mauritiana Iso105 males. Hybrid male progeny that inherit the transgene are orange eyed (genotype 2), while the sibling brothers are white eyed (genotype 1). Relative viability is the ratio of the number of hybrid sons inheriting the transgene compared to the control class.

Surprisingly, hybrid sons carrying the Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} transgene were fully viable at 18° relative to their control brothers and had substantially higher viability relative to control brothers at room temperature (138.8–144.3%, Table 2, cross 3). Lhr2 is therefore acting as a null allele or even an antimorph in this Hmr1 interaction assay. Reverting the C-terminal mutation to the wild-type sequence fully restored hybrid lethal effects to wild-type levels, with hybrid viability not significantly different than the wild-type Φ{sim-Lhr-HA} transgene (Table 2, cross 2 vs. 4, two-tailed FET, P = 1.0 at both room temperature and 18°). These results demonstrate that the C-terminal region is critical for the strong loss-of-function/antimorphic activity of Lhr2 in this assay.

We then compared the Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} allele to Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+16aa}, which differ only by the presence or absence of the 16-aa indel. We found that although hybrid sons inheriting Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA,+16aa} have viabilities comparable to the control class, the relative viabilities of hybrid sons inheriting this transgene are less than that for the Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} transgene. This reduction in viability is significant at 18° (Table 2, cross 3 vs. 5, two-tailed FET, P = 0.022). These results again show that the 16-aa indel does have a detectable effect on Lhr function in the background of the C-terminal mutation.

The molecular properties of the LHR2 protein

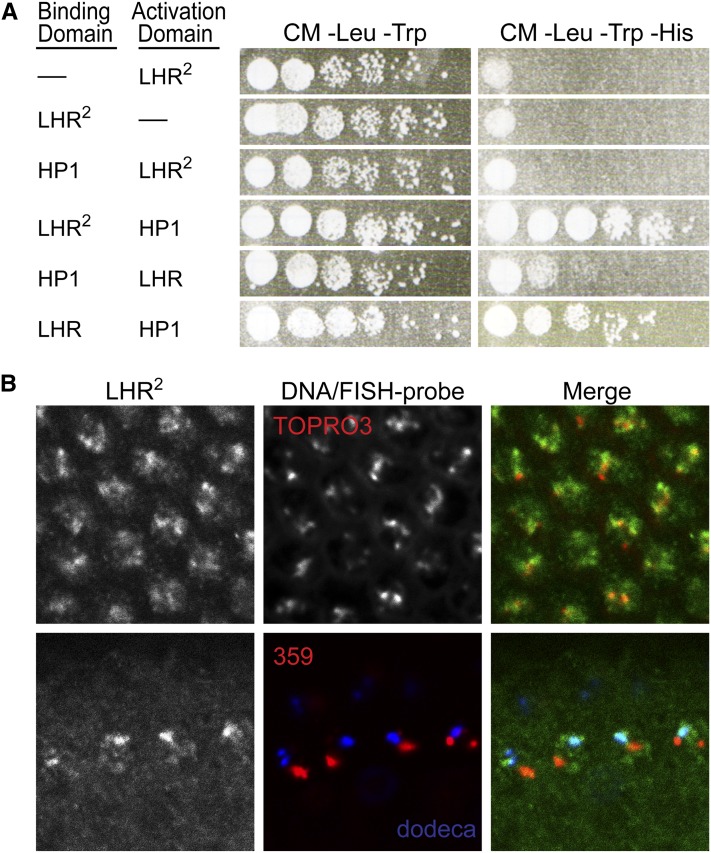

We next asked whether the LHR2 mutant protein is altered for molecular functions of LHR. LHR localizes to specific regions of heterochromatin through interaction with heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) (Brideau et al. 2006; Greil et al. 2007; Brideau and Barbash 2011). We therefore asked whether the reduced hybrid lethal activity of Lhr2 was reflecting a defect in heterochromatin association. We performed yeast two-hybrid assays and found that the interaction between LHR2 and HP1 was indistinguishable from the wild-type control (Figure 3A). Consistent with this result, LHR2-HA localized to heterochromatin in vivo and immuno-FISH experiments showed colocalization with the dodeca satellite in a manner indistinguishable from wild-type LHR (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012), providing further support for wild-type association with heterochromatin (Figure 3B). We conclude that the reduced hybrid lethal activity of Lhr2 is not because localization to heterochromatin is defective.

Figure 3 .

The sim-LHR2 protein interacts with HP1 and localizes to heterochromatin. (A) Interaction with HP1. Wild-type D. simulans LHR was used as a positive control. Yeast two-hybrid interactions were detected by activation of HIS3 and growth on media lacking histidine; loading controls [complete media (CM) −Leu −Trp] contain histidine. (B) Localization of sim-LHR2-HA to heterochromatin in D. melanogaster cycle 12–14 embryos. Top, sim-LHR2-HA was detected with anti-HA (green) and localizes to apical heterochromatin, detected by TOPRO3 staining (red) of DNA at the embryo surface. Bottom, immuno-FISH experiment with anti-HA (green) detecting sim-LHR2-HA in interphase nuclei. LHR2-HA shows no overlap with the 359-bp (red) satellite but partially colocalizes with the dodeca satellite (blue).

Discussion

The C-terminal mutation in Lhr2 identifies a region critical for Lhr function

In this study, we demonstrate conclusively that Lhr2 is a mutant allele of the Lhr hybrid lethality gene and further show that its mutant properties are due to changes in its CDS. Lhr2 is a weaker mutant allele than Lhr1 in its hybrid rescue ability, and in transgenic assays sim-Lhr2 complements Lhr1 more weakly than does a wild-type sim-Lhr allele (Table 1). By these criteria, Lhr2 would appear to be hypomorphic. In contrast, results from the Hmr1 interaction assay suggest that Lhr2 has no wild-type activity or is even antimorphic (Table 2).

We therefore devised modified Lhr2 alleles to individually assay specific regions for effects on hybrid lethal activity (Figure 1). We find that a highly conserved stretch of 10 residues in the C terminus of Lhr is critical for wild-type levels of hybrid lethal activity in both genetic assays. This conclusion is consistent with the observations of Nolte et al. (2008) who found wild-type hybrid lethal activity for two D. simulans Lhr alleles that have the deletion state for the 16-aa indel but are wild type for the C-terminal mutation. Because this region is highly similar between mel-Lhr and sim-Lhr, this result also supports published results that Lhr orthologs from both species can cause incompatibility (Brideau and Barbash 2011; Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). Our data here suggest that the C-terminal region is especially critical for interactions with Hmr because Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} has no wild-type activity for complementing Hmr1 (Table 2, cross 3), but whether this reflects a direct physical interaction remains unknown. The Lhr1 complementation assay is perhaps more straightforward to interpret since one is asking whether different Lhr alleles complement a loss-of-function allele of Lhr. Since only half of the hybrid sons inheriting the Φ{sim-Lhr2-HA} transgene are viable (Table 1 cross 2), it is clear that the C-terminal deletion does not fully account for the hybrid lethal activity of wild-type Lhr. Therefore additional regions of the LHR protein must also contribute to its incompatibility properties.

An effect of the 16-aa indel polymorphism on hybrid lethal activity was excluded by Nolte et al. (2008) using a population survey. They tested two D. simulans lines that retain the ancestral state of lacking the 16-aa insertion, but neither of them rescued hybrid sons. However, in the transgenic assay we find a significant difference in hybrid lethal activity of the Lhr2 allele with and without the insertion (Table 1 cross 2 vs. cross 4). We also detected a significant difference in the Hmr1 interaction assay (Table 2, cross 3 vs. cross 5). The lack of any phenotypic effects observed by Nolte et al. (2008) is most likely because the effect of the 16-aa indel is revealed only in a sensitized background. In this transgenic assay the C-terminal mutation in Lhr2 lowers the lethal activity of Lhr, providing us with the sensitivity to assess the contribution of the 16-aa deletion.

Differential hybrid lethal activity of Lhr orthologs: coding or regulatory?

Lhr has strongly asymmetric effects on hybrid viability, as mutations in sim-Lhr but not mel-Lhr produce viable hybrids (Brideau et al. 2006). This finding led to the hypothesis that the hybrid lethal activity of Lhr is due to coding sequence divergence that is specific to the D. simulans lineage. Surprisingly, we subsequently found that hybrid lethal activity is an ancestral property shared by the coding sequences of both Lhr orthologs (Brideau and Barbash 2011; Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). The different hybrid rescue effects of Lhr orthologs instead appear to be largely the consequence of divergent gene regulation that causes sim-Lhr to be expressed more highly in hybrids than mel-Lhr (Maheshwari and Barbash 2012). Our results here are consistent with these findings. First, we have identified the site of the C-terminal mutation in Lhr2 as critical for HI. Since this region is nearly identical between D. melanogaster and the sibling species, it was likely present in the ancestral Lhr allele. Second, our previous transgenic comparisons of mel-Lhr and sim-Lhr alleles did not exclude the possibility that coding sequence divergence may make some contribution to functional divergence. Our finding here that the 16-aa indel has a functional effect, but is only detectable on the background of the C-terminal deletion, is indicative of coding sequence divergence making a small contribution to differences in the hybrid lethal activity of Lhr. Interestingly though, since this difference between mel-Lhr and sim-Lhr is an indel it does not contribute to the signature of adaptive evolution discovered for Lhr (Brideau et al. 2006).

Rigorous identification of incompatible substitutions has only been attempted for yeast interstrain and interspecific HI genes. Single-amino-acid changes have been identified in each of two interacting genes that cause a defect in mismatch repair (Heck et al. 2006). In the case of AEP2, a translation factor that causes mitonuclear incompatibility between S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus, it was narrowed down to multiple mutations within a region of 148 aa. In the case of MRS1, a splicing factor that also causes mitonuclear incompatibility between the same two yeast species, it was pared down to only three nonsynonymous substitutions (Lee et al. 2008; Chou et al. 2010). There is no evidence of selection acting on either of these latter two HI genes and both have experienced relatively limited sequence divergence. There are at least six HI genes known that are rapidly diverging under selection (Presgraves 2010; Maheshwari and Barbash 2011). Although it is implicitly assumed that this divergence is the basis of HI, this hypothesis remains largely unexamined.

Functional effects of indels and polymorphisms

While indels are a common type of sequence variation, they are rarely considered in evolutionary studies. The reason for this is that their origins and functional consequences are poorly understood. Analysis of indels within protein sequences supports the view that they affect protein folding, and computational analysis of high-throughput protein interaction datasets suggests that indels modify protein interaction interfaces, thereby significantly rewiring the interaction networks (Hormozdiari et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2011). Moreover, studies comparing patterns of evolution of Catsper1, a sperm-specific calcium channel, found evidence of positive selection for elevated rates of indel substitutions within its intracellular domain across multiple primate and rodent species (Podlaha and Zhang 2003; Podlaha et al. 2005). The authors suggest that the selection for indels might be a consequence of their effect on the regulation of the Catsper1 channel, which can affect sperm motility, an important determinant in sperm competition.

Large structural polymorphisms are not unique to Lhr; other HI genes such as Hmr and Prdm9 have multiple in-frame indels, as does the segregation distorter RanGAP (Presgraves 2007; Maheshwari et al. 2008; Oliver et al. 2009). So far the primary focus of evolutionary analysis has been single-amino-acid substitutions, and indel variation has been largely ignored in the assessment of functional divergence. Recent high throughput analyses on human tissues has cataloged the occurrence of coding indels in hundreds of conserved and essential genes as well as in protein isoforms via alternative splicing, thus highlighting indels as an abundant source of structural variation (Wang et al. 2008; Mills et al. 2011). Our characterization of an indel polymorphism in Lhr presents one functional argument supporting the prediction that coding indels play an important evolutionary role. The low frequency of the deletion state of the 16-aa indel in D. simulans and its monomorphic state in D. melanogaster do not suggest an obvious role for selection in maintaining it. Our experiments here nevertheless demonstrate that this indel does affect Lhr function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Smaldone and Shuqing Ji for help scoring flies and Tawny Cuykendall, Heather Flores, P. Satyaki, Michael Nachman, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2R01GM074737.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. W. Nachman

Literature Cited

- Barbash D. A., 2010. Genetic testing of the hypothesis that hybrid male lethality results from a failure in dosage compensation. Genetics 184: 313–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayes J. J., Malik H. S., 2009. Altered heterochromatin binding by a hybrid sterility protein in Drosophila sibling species. Science 326: 1538–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K., 2007. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 3312–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brideau N. J., Barbash D. A., 2011. Functional conservation of the Drosophila hybrid incompatibility gene Lhr. BMC Evol. Biol. 11: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brideau N. J., Flores H. A., Wang J., Maheshwari S., Wang X., et al. , 2006. Two Dobzhansky-Muller genes interact to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. Science 314: 1292–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou J.-Y., Hung Y.-S., Lin K.-H., Lee H.-Y., Leu J.-Y., 2010. Multiple molecular mechanisms cause reproductive isolation between three yeast species. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil F., de Wit E., Bussemaker H. J., van Steensel B., 2007. HP1 controls genomic targeting of four novel heterochromatin proteins in Drosophila. EMBO J. 26: 741–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck J. A., Argueso J. L., Gemici Z., Reeves R. G., Bernard A., et al. , 2006. Negative epistasis between natural variants of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH1 and PMS1 genes results in a defect in mismatch repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 3256–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormozdiari F., Salari R., Hsing M., Schönhuth A., Chan S. K., et al. , 2009. The effect of insertions and deletions on wirings in protein-protein interaction networks: a large-scale study. J. Comput. Biol. 16: 159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter P., Ashburner M., 1987. Genetic rescue of inviable hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Nature 327: 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise D., David J. R., Lemeunier F., Tsacas L., Ashburner M., 1986. The reproductive relationships of Drosophila sechellia with D. mauritiana, D. simulans, and D. melanogaster from the Afrotropical region. Evolution 40: 262–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-Y., Chou J.-Y., Cheong L., Chang N.-H., Yang S.-Y., et al. , 2008. Incompatibility of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes causes hybrid sterility between two yeast species. Cell 135: 1065–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay T. F. C., Richards S., Stone E. A., Barbadilla A., Ayroles J. F., et al. , 2012. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature 482: 173–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari S., Barbash D. A., 2011. The genetics of hybrid incompatibilities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45: 331–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari S., Barbash D. A., 2012. Cis-by-Trans regulatory divergence causes the asymmetric lethal effects of an ancestral hybrid incompatibility gene. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari S., Wang J., Barbash D. A., 2008. Recurrent positive selection of the Drosophila hybrid incompatibility gene Hmr. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25: 2421–2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuilton P., St Pierre S. E., Thurmond J., Consortium FlyBase, 2012. FlyBase 101–the basics of navigating FlyBase. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D706–D714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R. E., Pittard W. S., Mullaney J. M., Farooq U., Creasy T. H., et al. , 2011. Natural genetic variation caused by small insertions and deletions in the human genome. Genome Res. 21: 830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte V., Weigel D., Schlötterer C., 2008. The impact of shared ancestral variation on hybrid male lethality–a 16 codon indel in the Drosophila simulans Lhr gene. J. Evol. Biol. 21: 551–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver P. L., Goodstadt L., Bayes J. J., Birtle Z., Roach K. C., et al. , 2009. Accelerated evolution of the Prdm9 speciation gene across diverse metazoan taxa. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlaha O., Zhang J., 2003. Positive selection on protein-length in the evolution of a primate sperm ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 12241–12246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlaha O., Webb D. M., Tucker P. K., Zhang J., 2005. Positive selection for indel substitutions in the rodent sperm protein catsper1. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22: 1845–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves D. C., 2007. Does genetic conflict drive rapid molecular evolution of nuclear transport genes in Drosophila? Bioessays 29: 386–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves D. C., 2010. The molecular evolutionary basis of species formation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11: 175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant A. H., 1920. Genetic studies on Drosophila simulans. I. Introduction. Hybrids with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 5: 488–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., et al. , 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting C. T., Tsaur S. C., Wu M. L., Wu C. I., 1998. A rapidly evolving homeobox at the site of a hybrid sterility gene. Science 282: 1501–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E. T., Sandberg R., Luo S., Khrebtukova I., Zhang L., et al. , 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456: 470–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T. K., 1979. A gene that rescues the lethal hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Jpn. J. Genet. 54: 325–331 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Huang J., Wang Z., Wang L., Gao P., 2011. Impact of indels on the flanking regions in structural domains. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.