Abstract

α-tropomyosin (αTm) is central to Ca2+-regulation of cardiac muscle contraction. The familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation αTm E180G enhances Ca2+-sensitivity in functional assays. To investigate the molecular basis, we imaged single molecules of human cardiac αTm E180G by direct probe atomic force microscopy. Analyses of tangent angles along molecular contours yielded persistence length corresponding to ~35% increase in flexibility compared to wild-type. Increased flexibility of the mutant was confirmed by fitting end-to-end length distributions to the worm-like chain model. This marked increase in flexibility can significantly impact systolic and possibly diastolic phases of cardiac contraction, ultimately leading to hypertrophy.

Keywords: muscle thin filament, Ca2+-regulation, persistence length, atomic force microscopy

1. Introduction

α-Tropomyosin (αTm) is a dimeric, α-helical coiled-coil protein that binds actin and is an integral component of thin filaments for Ca2+-regulated contraction of striated muscle. One troponin complex (Tn) and one αTm molecule form a structural regulatory unit with seven adjacent actin monomers in the thin filament, where αTm binds to and spans all seven actins. The Ca2+ regulation mechanism of cardiac muscle contraction can be described by a three-state model of regulatory units [1]. In the ‘blocked’ state, when Ca2+ is effectively absent in the cytoplasm (cardiac diastole), αTm sterically blocks myosin-binding sites on actin, inhibiting cross-bridge formation and thus contraction. During systole, Ca2+ ions are released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and bind to Tn. Subsequent conformational change of Tn leads to the ‘closed’ state, in which azimuthal movement of αTm on the thin filament uncovers part of myosin-binding sites on actin and allows formation of weak cross-bridges. In the ‘open’ state, strong cross-bridge formation between myosin and actin is associated with further αTm movement away from myosin binding sites, and full activation of regulatory units. Activation of one regulatory unit may cooperatively influence activation of adjacent regulatory units through end-to-end interactions between adjacent αTm molecules. Taken together, this suggests that mechanical flexibility of αTm is likely to be an essential parameter in this regulatory process within and between regulatory units, and thus could influence normal function of the human heart [2,3].

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC) is an inherited disease that affects ~0.2% of the population [4]. It is typically characterized by thickening of the myocardium and may be relatively benign, or can lead to heart failure or sudden cardiac death [4]. Genetic linkage studies have demonstrated that FHC is associated with any of a large number of mutations, primarily in cardiac cytoskeletal proteins including thick filament proteins β-myosin heavy chain, myosin essential and regulatory light chains, and cardiac myosin-binding protein C, and thin filament proteins including all three cardiac Tn subunits (cTnT, cTnI, and cTnC) and αTm [5–11]. The E180G mutation in αTm is close to the primary cTnT binding site in the C-terminal end of the molecule. This missense mutation leads to severe cardiac hypertrophy and early death in transgenic mice [12]. At the molecular level, the mutant protein has a lower binding affinity for actin [5,13–15] and decreased thermal stability [13,14,16] compared to wild-type (WT) protein. In vitro studies with mutant αTm using myofibrillar ATPase activity, motility assays and permeabilized cardiac cell mechanics showed markedly enhanced Ca2+-sensitivity [6,17–19] and reduced functional cooperativity [19]. A comparable increase in Ca2+-sensitivity of actomyosin binding kinetics has also been reported with this FHC-associated mutation of αTm [20].

A mechanistic relationship between the E180G mutation, the above observations, and cardiac hypertrophy has not yet been established, and more fundamentally there is no direct experimental information about the mutation’s effects on the structure and mechanical properties of single αTm molecules. Modeling studies suggest that the presence of, and variations in, myofilament compliance could alter myocyte function at all levels of Ca2+-activation [21–24] and some aspects of muscle cell mechanics are most simply explained by Ca2+-dependent changes in sarcomere compliance [25]. Estimates of thin filament flexibility suggest that Tn and αTm modulate compliance in a Ca2+-dependent manner [26] and this could be directly influenced by flexibility of αTm. We therefore hypothesized that the E180G mutation alters the mechanical flexibility of αTm, which could contribute to functional differences between thin filaments containing the E180G mutant versus WT as suggested by modeling studies on other FHC-related, thin filament mutations [23].

Recently we reported the persistence length (Lp), which is a measure of the rigidity of the molecule, of WT human cardiac αTm [3]. Here we present the first mechanical flexibility measurements of the E180G mutant using direct probe, atomic force microscopy (AFM). The mutant is more flexible than WT, with ~35% shorter Lp. We propose that, corresponding to the increased flexibility, a lesser extent of Ca2+-induced conformational change of Tn is required to perturb αTm to initiate thin filament activation during systole, leading to enhanced Ca2+-sensitivity [2]. Hypersensitivity to Ca2+ could overwork cardiac muscle, resulting in FHC. Preliminary data were presented in an abstract [27].

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental techniques were essentially as described in a previous publication [3] and are briefly summarized below.

2.1. Protein preparation

WT human cardiac αTm cDNA was cloned previously into a bacterial expression vector [28] and the E180G mutation was introduced using site directed mutagenesis (Stratagene QuickChange Kit, La Jolla, CA) [19]. Bacterial expression and purification of recombinant mutant αTm was carried out as described.

2.2. Atomic force microscopy

Single molecules of E180G mutant αTm were imaged with a MFP-3D (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) atomic force microscope on poly-lysine (p-Lys) coated mica substrate. A 200 μl aliquot of 1 nM αTm E180G was deposited on the substrate and incubated for 600 s; this incubation time was demonstrated to be sufficient for obtaining consistent estimates of Lp for WT αTm under the same experimental conditions [3]. The sample was then rinsed, and dried with compressed nitrogen gas. AFM images were acquired at 0.5 nm/pixel in AC mode.

2.3. Image processing and data analysis

Images of individual αTm molecules were processed and the data were analyzed to yield Lp. Three separate methods of data analysis were applied to populations of αTm molecules from independently prepared samples: second moment of tangent angles, tangent angle correlation, and end-to-end length distribution.

Briefly, the shape of each αTm molecule was traced with sub-pixel precision to obtain a polynomial skeleton representation of the molecular contour. Angles, θ(s), between the tangents of the molecular contour at two points separated by segment length s were computed in 0.5 nm steps. End-to-end length (Le-e) and contour length (Lc) of each αTm molecule were calculated, respectively, as the linear distance between the two ends of the molecule and the integrated length along the polynomial fit.

Equilibration of αTm molecules on the substrate was verified by the ratio between tangent angle fourth moment (<θ4(s)>) and squared second moment <θ2(s)>2 [29] (Supplemental Materials). Lp estimate was obtained by fitting the dependence of <θ2(s)> on s according to the linear relation:

| Eq. 1 |

A zero intercept confirmed that the molecules were equilibrated on the substrate; the inverse of the slope gave Lp.

In tangent angle correlation analysis, the average of cosθ(s), <cosθ(s)>, is assumed to be an exponential function of s:

| Eq. 2 |

<cosθ(s)>, at a given s, was computed both along the contour of each molecular skeleton and over different skeletons. Lp was obtained by weighted linear regression on the logarithmically transformed data.

A third estimate of Lp was obtained by analysis of end-to-end length distributions. Scaled end-to-end length (le-e) was obtained as the ratio between Le-e and Lc for each αTm molecule. Distributions of le-e were fitted to that expected of a two-dimensional worm-like chain (WLC) [30]:

| Eq. 3 |

where lp = Lp/Lc, η is a normalization factor, and D3/2(x) is a parabolic cylinder function. In short, analyses of tangent angle second moment, tangent angle correlation, and end-to-end length distribution resulted in three independent estimates of Lp.

3. Results

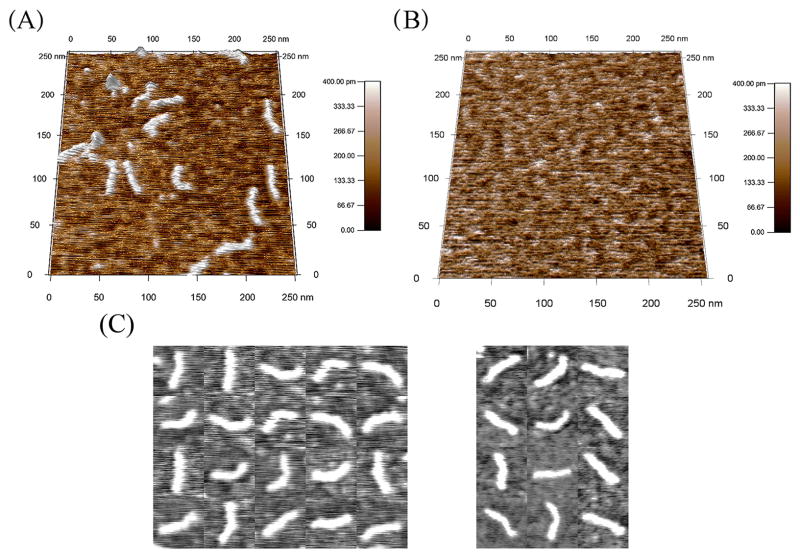

Fig. 1A and the left-most collage in Fig. 1C show AFM scans of αTm E180G on p-Lys coated mica. Lengths of clearly distinguishable elongated structures on the substrate are consistent with that expected for single αTm molecules [31]. For comparison, p-Lys coated mica (no αTm) is shown in Fig. 1B. In general, individual molecules of αTm E180G appeared more bent in the images when compared to WT (Fig. 1C). A small subset of mutant molecules exhibits a noticeable kink along the molecular contour. As our spatial resolution was limited by tip convolution and the N- and C-termini of the molecule were indistinguishable, we were not able to quantitatively correlate the location of kinks in these molecules with that expected for the E180G mutation along the molecular contour (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

AFM images of human cardiac αTm E180G molecules. (A) αTm E180G was imaged dry on poly-lysine coated mica. Lc of E180G obtained from these images were 39.6 ± 0.1 nm (N = 537), 39.7 ± 0.1 nm (N = 1909), and 39.5 ± 0.1 nm (N = 589), consistent with that expected for single αTm molecules [31]. (B) Poly-lysine coated mica substrate was imaged without the protein as control. (C) Collages of subsets of (left) E180G and (right) WT αTm molecules show that molecular contours were continuous, although the mutant molecules appear more curved on average than the WT counterparts and some exhibit a noticeable kink.

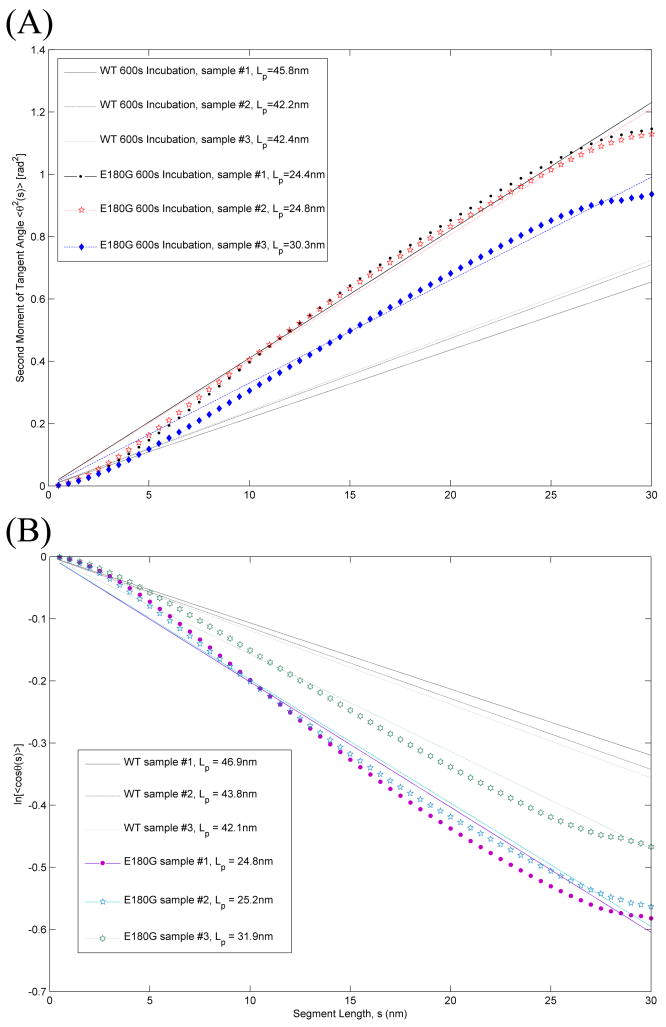

Fig. 2A shows the results of tangent angle second moment analysis of images obtained from three samples independently prepared under identical experimental conditions. In this analysis, Lp values obtained for the three samples of E180G αTm were 24.4 ± 0.2 nm (N = 537), 24.8 ± 0.1 nm (N = 1909), and 30.3 ± 0.2 nm (N = 589). The ~5.9 nm difference between Lp values of these samples represents experimental variations inherent to our technique and this particular data analysis scheme, and is comparable to that in our previous measurements of WT αTm [3]. These values of Lp represent ~ 37% decrease (corresponding to an increase in flexibility) compared to WT, which has Lp values of 39.5 – 44.5 nm. The values of <θ2(s)> for E180G αTm are noticeably different from those of WT for s > 5 nm, and deviate somewhat from a linear dependence on s, with a downward curvature, at s = 25 – 30 nm. This indicates that the effect of the E180G mutation is not localized at the mutation site and extends to most of the molecular contour.

Fig. 2.

Lp by (A) tangent angle second moment analysis and (B) tangent angle correlation analysis. Respective <θ2(s)> and ln(<cosθ (s)>) data obtained from three αTm E180G samples independently prepared under identical conditions are plotted as a function of segment length along the molecular contour. Results for WT αTm [3] are replotted for comparison. Lp values for αTm E180G were 24.4 ± 0.2 nm (N = 537, R2 = 0.99), 24.8 ± 0.1 nm (N = 1909, R2 = 0.99) and 30.3 ± 0.2 nm (N = 589, R2 = 0.99) from the second moment analysis (Eq 1) and 24.8 ± 0.5 nm (N = 537, R2 = 0.97), 25.2 ± 0.4 nm (N = 1909, R2 = 0.98), and 31.9 ± 0.6 nm (N = 589, R2 = 0.98) from the correlation analysis (Eq 2).

Tangent angle correlation analysis is shown in Fig. 2B. Lp values obtained for the three samples of αTm E180G were 24.8 ± 0.5 nm (N = 537), 25.2 ±0.4 nm (N = 1909), and 31.9 ± 0.6 nm (N = 589). These results agree very well with Lp estimates obtained with analysis of second moment, and again represents ~37% decrease in measured Lp compared to those of WT αTm. The ~6.1 nm difference between the three samples is comparable to that in the analysis of tangent angle second moment.

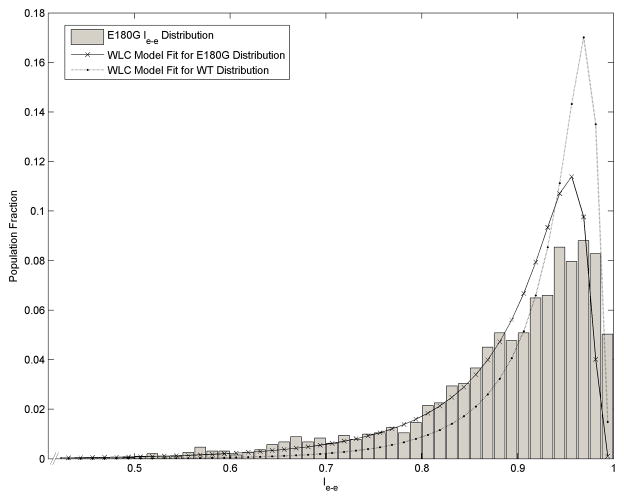

To further verify our result, distributions of le-e from the same samples were fitted to the WLC model (Eq. 3). The resulting values of lp obtained from the three samples of αTm E180G were 0.705 ± 0.060 (N = 537), 0.668 ± 0.041 (N = 1909), and 0.993 ± 0.060 (N = 589) (Fig. 3). Assuming 40 nm for the contour length of αTm E180G (Fig. 1), the corresponding Lp values would be 28.2 ± 2.4 nm, 26.7 ± 1.6 nm, and 39.7 ± 2.4 nm, respectively. The ~13 nm variation in Lp obtained with this analysis is consistent with that previously reported for the WT protein [3]. Most importantly, this result represents a 34% decrease in measured Lp when compared to the values for WT human cardiac αTm obtained with the same analysis. This is in close agreement 2( with the results obtained from analyses of both <θ2(s)> and correlation along molecular contour. We believe this drastic decrease in measured Lp is unlikely to be fully accounted for solely by a change in inherent curvature of the E180G mutant (Supplemental Materials). In short, independent analyses of tangent angles and WLC fitting of the le-e distributions consistently indicate that the E180G mutant is more flexible than WT αTm at the single molecule level.

Fig. 3.

Lp by end-to-end length analysis. Normalized distribution of scaled end-to-end length (le-e) from one of the E180G mutant samples (N = 1909). The mutant distribution fitted to the WLC model (Eq. 3) is significantly broader (solid line) than the WT counterpart (dotted line). The lp value for αTm E180G mutant from the fit was 0.67 ± 0.04 (R2 = 0.82). Errors were estimated by the jackknife method.

4. Discussion

In this study, we obtained AFM images of individual molecules of human cardiac αTm E180G and measured their persistence length. Tangent angle second moment, tangent correlation and end-to-end length distribution resulted in Lp values of 24.4 – 30.3 nm, 24.8 – 31.9 nm and 26.7 – 39.7 nm, respectively. Based on the ~35% smaller Lp value for the FHC-related E180G mutant relative to WT αTm, we conclude that the mutant is significantly more flexible at the level of single molecules and suggest that this could accentuate a local, spatial gradient of activation within a single regulatory unit during systole, and could increase the likelihood of diastolic dysfunction.

AFM images of clearly distinguishable, elongated structures having lengths consistent with single molecules of αTm were obtained on p-Lys coated mica surfaces. As shown previously, a large sample size (N > 100) is necessary for a reliable Lp measurement of a semi-flexible molecule such as αTm. Therefore, we analyzed the contour shapes of 537 – 1909 molecules of αTm E180G from three samples independently prepared under identical conditions, and quantified their flexibilities by three independent methods: tangent angle second moment (Eq. 1), tangent correlation analysis (Eq. 2), and end-to-end length distribution (Eq. 3). Fitting the end-to-end length distribution to the WLC model (Eq. 3) resulted in a slightly larger Lp compared to the tangent angle analyses (Eqs. 1 and 2) for both mutant and WT proteins. All three analyses showed a consistent 34 – 37% shorter Lp for αTm E180G compared to the corresponding analyses for WT. In tangent angle second moment and tangent correlation analyses, the values of <θ2(s)> and ln<cosθ(s)> for the E180G mutant are noticeably different from that of the WT protein for s > 5 nm. Given that the E180G mutation corresponds to a location ~25 nm from the N-terminus of αTm, most of the shorter segments (s < 20 nm) did not overlap with the mutation site. This suggests that the E180G mutation impacts the mechanical properties along most of the molecular contour so that its effect is not localized at the mutation site. Values of <θ2(s)> and ln<cosθ(s)> for the E180G mutant also have a slight downward curvature at s = 25 – 30 nm. As all longer segments (s > 25 nm) contain the E180G mutation, this could reflect an alteration to local structure near the E180G mutation.

The observed change in the measured Lp of human cardiac αTm due to a single missense mutation seems drastic. It is possible that this change is partly due to an altered intrinsic curvature of the molecule. In the extreme case that the entire ~35% reduction in measured Lp was due to increased intrinsic curvature, it can be estimated that the E180G mutant would have to be at least 80% more bent compared to the WT protein (Supplemental Materials). Such a large increase of inherent curvature in the E180G mutant is unlikely and indeed inconsistent with our AFM images. Therefore, we believe that the decrease in measured Lp of the E180G mutant is due to changes in both the inherent curvature and, likely more significantly, mechanical flexibility of the molecule. Additional techniques such as force spectroscopy are needed to reveal the structural basis underlying the mutation-induced change in Lp.

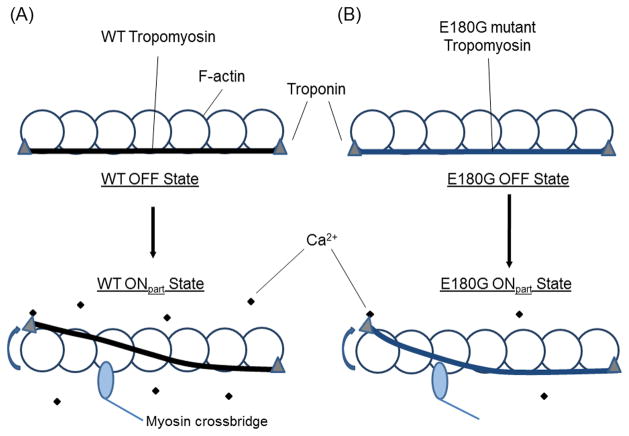

During thin filament activation, αTm is mechanically displaced following Ca2+-binding to the Tn complex to uncover myosin-binding sites of the underlying actin filament (Fig. 4). The reduced correlation along the αTm molecule due to shorter Lp could decrease binding cooperativity of αTm to adjacent actin monomers and thus overall affinity of αTm for F-actin [2], as observed for the E180G mutant in the absence of Tn [5,13–15]. The functional regulatory unit in normal cardiac muscle is shorter than a single αTm [32]. Our results lead to a prediction of further reduction in cooperative transmission of activation along thin filaments containing αTm E180G due to a spatial gradient of activation within partially activated, individual regulatory units during cardiac systole (Fig. 4), and increased Ca2+-sensitivity of thin filament activation at low Ca2+ due to lower energy of local displacement of αTm [2]; in addition, there could be a slight reduction in maximal force produced by cardiac sarcomeres at saturating Ca2+ levels although this scenario is unlikely in vivo. Higher Ca2+-sensitivity means that human cardiac thin filaments harboring the FHC-related αTm E180G mutant will become activated earlier during systole, remain activated longer during the relaxation phase, and in extreme cases could possibly stay partially activated during diastole [18,33,34]. FHC patients express both WT and mutant αTm and thus some heterodimers are present [8,11]. Flexibility of a heterodimer is presumably between that of WT and mutant homodimers, although not necessarily the average. In both cases, the increase in flexibility would be expected to have marked effects not only on the overall mechanics of the heart and cardiac output, but also increased workload of cardiac muscle en route to hypertrophy.

Fig. 4.

Model of αTm motion within a partially activated, single regulatory unit of a cardiac thin filament. This cartoon illustrates the proposed effect of increased αTm flexibility due to the E180G mutation on sub-saturating Ca2+-activation of cardiac thin filaments. Structural details such as the coiling of αTm around F-actin, the helical turns of actin, the span of Tn along the thin filament and its interactions with actin are omitted for clarity. Due to the increased flexibility, propagation of activation signal along the length of αTm E180G will be impeded [2]. The mutant has lower affinity and non-cooperative binding to actin, thus a perturbation requires smaller mechanical moment. Therefore, at low Ca2+, regulatory units on thin filaments harboring mutant αTm are more likely to be activated compared to WT, although there may be a local spatial gradient of partial activation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

First direct probe AFM imaging of single molecules of E180G mutant tropomyosin.

E180G mutation markedly reduces persistence length, implying increased flexibility.

Mutant persistence length is less than the length of a tropomyosin molecule.

Flexibility implies spatial gradient of partial activation within one regulatory unit.

Increased flexibility explains many aspects of altered cardiac dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Aya K. Takeda for valuable assistance with protein expression and purification, Asylum Research, Inc., for technical support, and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 0815127E for financial support. Huan-Xiang Zhou was supported in part by NIH Grant GM88187.

Abbreviations

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- αTm

α-tropomyosin

- cTnC

cardiac troponin C subunit

- cTnI

cardiac troponin I subunit

- cTnT

cardiac troponin T subunit

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- FHC

familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Lc

contour length

- le-e

end-to-end length normalized to contour length

- Le-e

end-to-end length

- lp

persistence length normalized to contour length

- Lp

persistence length

- p-Lys

poly-lysine

- s

segment length

- Tn

troponin complex

- WLC

worm-like chain

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McKillop DF, Geeves MA. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys J. 1993;65:693–701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loong CKP, Badr MA, Chase PB. Tropomyosin flexural rigidity and single Ca2+ regulatory unit dynamics: implications for cooperative regulation of cardiac muscle contraction and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Front Physiol. 2012;3:80. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loong CKP, Zhou HX, Chase PB. Persistence Length of Human Cardiac α-Tropomyosin Measured by Single Molecule Direct Probe Microscopy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1997;350:127–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bing W, Redwood CS, Purcell IF, Esposito G, Watkins H, Marston SB. Effects of two hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in α-tropomyosin, Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly, on Ca2+ regulation of thin filament motility. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:760–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bing W, Knott A, Redwood C, Esposito G, Purcell I, Watkins H, Marston S. Effect of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in human cardiac muscle α- tropomyosin (Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly) on the regulatory properties of human cardiac troponin determined by in vitro motility assay. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1489–98. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köhler J, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in troponin I (K183Δ, G203S, K206Q) enhance filament sliding. Physiol Genomics. 2003;14:117–28. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Towbin JA, Bowles NE. The failing heart. Nature. 2002;415:227–33. doi: 10.1038/415227a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolska BM, Wieczorek DMF. The role of tropomyosin in the regulation of myocardial contraction and relaxation. Pflügers Arch. 2003;446:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willott RH, Gomes AV, Chang AN, Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR, Potter JD. Mutations in Troponin that cause HCM, DCM AND RCM: what can we learn about thin filament function? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:882–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tardiff JC. Thin filament mutations: developing an integrative approach to a complex disorder. Circ Res. 2011;108:765–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prabhakar R, Boivin GP, Grupp IL, Hoit B, Arteaga G, Solaro JR, Wieczorek DF. A familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy α-tropomyosin mutation causes severe cardiac hypertrophy and death in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1815–28. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremneva E, Boussouf S, Nikolaeva O, Maytum R, Geeves MA, Levitsky DI. Effects of two familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in α-tropomyosin, Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly, on the thermal unfolding of actin-bound tropomyosin. Biophys J. 2004;87:3922–33. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golitsina N, et al. Effects of two familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-causing mutations on α-tropomyosin structure and function. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3850. doi: 10.1021/bi9950701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathur MC, Chase PB, Chalovich JM. Several cardiomyopathy causing mutations on tropomyosin either destabilize the active state of actomyosin or alter the binding properties of tropomyosin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilario E, da Silva SL, Ramos CH, Bertolini MC. Effects of cardiomyopathic mutations on the biochemical and biophysical properties of the human α-tropomyosin. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4132–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang AN, Harada K, Ackerman MJ, Potter JD. Functional consequences of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in α-tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34343–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai F, Weis A, Takeda AK, Chase PB, Kawai M. Enhanced Active Cross-Bridges during Diastole: Molecular Pathogenesis of Tropomyosin’s HCM Mutations. Biophys J. 2011;100:1014–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, et al. Facilitated cross-bridge interactions with thin filaments by familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in α-tropomyosin. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:435271. doi: 10.1155/2011/435271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boussouf SE, Maytum R, Jaquet K, Geeves MA. Role of tropomyosin isoforms in the calcium sensitivity of striated muscle thin filaments. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chase PB, Macpherson JM, Daniel TL. A spatially explicit nanomechanical model of the half-sarcomere: myofilament compliance affects Ca2+-activation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:1559–68. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000049039.89173.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniel TL, Trimble AC, Chase PB. Compliant realignment of binding sites in muscle: transient behavior and mechanical tuning. Biophys J. 1998;74:1611–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(98)77875-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kataoka A, Hemmer C, Chase PB. Computational simulation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in troponin I: influence of increased myofilament calcium sensitivity on isometric force, ATPase and [Ca2+]i. J Biomech. 2007;40:2044–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner BCW, Daniel TL, Regnier M. Filament Compliance Influences Cooperative Activation of Thin Filaments and the Dynamics of Force Production in Skeletal Muscle. PLoS Comp Biol. 2012;8:e1002506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martyn DA, Chase PB, Regnier M, Gordon AM. A simple model with myofilament compliance predicts activation-dependent crossbridge kinetics in skinned skeletal fibers. Biophys J. 2002;83:3425–34. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isambert H, Venier P, Maggs AC, Fattoum A, Kassab R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Flexibility of actin filaments derived from thermal fluctuations. Effect of bound nucleotide, phalloidin, and muscle regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11437–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loong C, Zhou HX, Chase PB. Flexibility Change in Human Cardiac α-Tropomyosin E180G Mutant: Possible Link to Cardiac Hypertrophy. Biophys J. 2011;100:586a. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoffstall B, et al. Ca2+ sensitivity of regulated cardiac thin filament sliding does not depend on myosin isoform. J Physiol. 2006;577:935–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frontali C, Dore E, Ferrauto A, Gratton E, Bettini A, Pozzan MR, Valdevit E. An absolute method for the determination of the persistence length of native DNA from electron micrographs. Biopolymers. 1979;18:1353–73. doi: 10.1002/bip.1979.360180604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilhelm J, Frey E. Radial Distribution Function of Semiflexible Polymers. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:2581–2584. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry SV. Vertebrate tropomyosin: distribution, properties and function. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2001;22:5–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1010303732441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillis TE, Martyn DA, Rivera AJ, Regnier M. Investigation of thin filament near-neighbour regulatory unit interactions during force development in skinned cardiac and skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2007;580:561–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho CY, et al. Echocardiographic strain imaging to assess early and late consequences of sarcomere mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:314–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell SG, McCulloch AD. Multi-scale computational models of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genotype to phenotype. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8:1550–61. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.