INTRODUCTION

With the advent of digital libraries, health sciences librarians have a greater opportunity than ever before to provide clinicians with information that can directly impact patient care. To take advantage of this opportunity, librarians need to understand the tasks and associated information needs of users in the clinical workplace. The authors believe that knowledge about the concept of what we call “bundles” can increase this understanding.

While doing observational fieldwork in health care settings, members of our research team have observed a common pattern where information is grouped into various forms of bundles. These bundles act as organized collections of highly selective bits of information, usually derived from multiple sources, created by experts to support the performance of specific tasks in specific contexts. Bundles are often created in informal, temporary form, using any available media, including paper but also latex gloves, paper towels, sticky notes, exam-room table covers, or tissue boxes. Formal, permanent types of bundles also exist. One example is a resident's worksheet, which is often a premade form that defines separate areas (spaces for bundles) to hold the clinician's handwritten notes. Common bundles on such forms include “to do” lists for individual patients and notes on multiple patients. They are a form of temporary records and mnemonic devices at the same time. Bundles appear to serve many purposes, from assisting a clinician with “thinking through” a problem at hand, to sharing a representation of current data and its interpretation, to reminding an individual of critical information in an environment characterized by frequent interruptions. We believe that by learning more about bundles and how they are used, librarians can find better ways of helping clinicians manage information in the course of their work.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

Our Digital Libraries Initiative grant has supported two simultaneous activities: fieldwork in hospital settings and development of a computer application. The fieldwork team—comprised of physicians, a nurse, and a medical librarian—has used participant observation, oral history interviews, and focus groups in a series of projects concerning information issues in clinical settings [1]. Approximately 140 hours of observation were done in the intensive care unit of a busy metropolitan hospital. Nurses and physicians were primarily shadowed, but respiratory therapists, chaplains, dieticians, social workers, and procedural specialists were also shadowed. Extensive field notes were taken, subsequently transcribed, and then analyzed by multiple researchers with the aid of qualitative analysis software. Oral history interviews and focus groups were also conducted, taped, transcribed, and analyzed. Results of the analyses were presented to informants for feedback.

Results of the observational work have been shared in an iterative process with the computer science members of our team, who are exploring the notion of “superimposed information.” The term superimposed information is used to describe information that is conceptually distinct from existing (or base) information sources. It can be used for a variety of purposes including highlighting and supplementing existing information. Non-digital examples include concordances, citation indexes, cross-references, and even commentaries. Digital superimposed information has an added benefit in that it can contain actual links to the selected information elements. For example, a bookmark list (a simple example of superimposed information) allows quick access to desired information with one click.

We see bundles as a form of superimposed information. They also contain additional information such as highlighting for emphasis and annotations, both of which are often exposed through juxtaposition of information. Our computer science team members have built an application called the Superimposed Layer Information Manager scratchPad (SLIMPad) to help users create bundles. SLIMPad allows individuals to select information from original sources (e.g., portable document format documents, Excel spreadsheets, and extensible markup language data) and place it on the scratchpad in a freeform manner, where it can be further organized into bundles. The key contribution of SLIMPad is that information elements copied onto it remain linked, electronically, to the underlying information [2].†

BUNDLES

The context in which bundles have been discovered is radically different from the library setting, where the information seeker can use resources without being interrupted. In the intensive care unit (ICU), the level of activity, noise, and movement is astounding. Deliberate information seeking in a traditional sense rarely takes place, although clinicians are constantly engaged in seeking information specific to the tasks at hand. The rapid turnover of patients and the acuity of their problems cause pressures that prevent clinicians from spending a significant amount of time searching for information [3]. The number of interruptions is staggering, but bundles help clinicians formulate thoughts, remember details, and deal with interruptions.

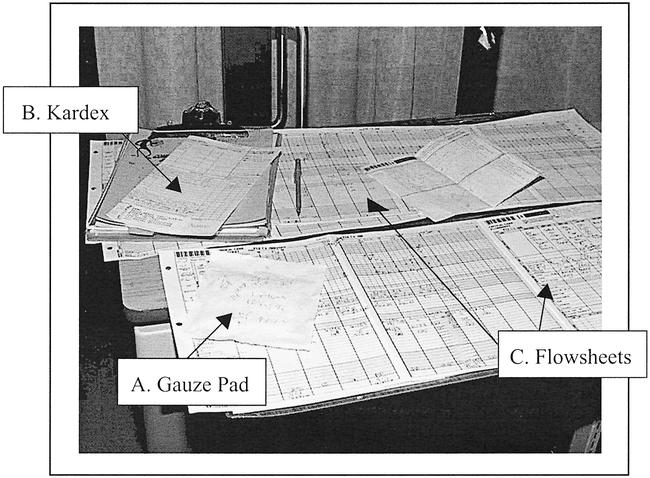

Figure 1, a candid picture of a patient's bedside table, shows three examples of bundles. One is informal and seems disorganized; the second is somewhat formal but ephemeral; and the third is formal and becomes a permanent part of the record.

Messy bundle (A): On top is a typical “messy bundle”: a four-by-four inch gauze pad with numbers written on it. We see many examples of messy bundles, because they can be put together quickly on whatever medium is available. We see them on skin (especially hands), fabric, plastic, and cardboard as well as paper (especially sticky notes). The pictured bundle is an efficient source of information for the health care worker; the numbers and lines are meaningful to clinicians; and there is no useless information. Data entry is extremely flexible; the object is portable and has a high degree of immediacy and relevance. The information on the gauze pad includes seventeen numbers, but only two are labeled. The ICU staff members readily recognize these as hemodynamic data from a patient with a pulmonary artery catheter. The labels “CVP” and “wedge” provide context, and the values are arranged in a meaningful and standard way.

Kardex (B): A somewhat more structured bundle known as “the Kardex” is lying on top of the clipboard. Kardex is a familiar term to librarians who use it to check-in journal issues, although here the format differs. The card is annotated in pencil and updated and erased constantly; it is used by many people; and, although it is of central importance, it does not get permanently filed. It is a record of the management plan for the patient, a place where information is pulled together, so a clinician can quickly learn about the patient. It contains information about active medications and treatments.

Flowsheet (C): Examples of the third type of bundle, the nursing flowsheet, include the two long-paper forms. Like the other bundles, the flowsheet is a working document, but unlike the others, it becomes part of the permanent record. It tracks observations, readings of patient vital signs, and so on, over time.

Figure 1.

Examples of bundles

IMPLICATIONS FOR LIBRARIANS

Several forms of bundles are widely used in health care. We found that in an ICU, the medical chart is not the ultimate source of information concerning a patient, and instead bundles, even the ephemeral ones, are often the most critical information sources available. In addition, the process of putting together the bundle serves an important function. We believe the discovery of bundles offers several opportunities for health sciences librarians.

The opportunity to study bundles as model resources: Bundles are in many ways a perfect information resource: flexible, current, accurate, highly visible, selective, portable, and easily and instantaneously understood by readers. Bundles deserve further study, because they may serve as models for services and information management tools in the future. For example, they can generate ideas for new services for clinical librarians or informationists to offer [4].

The opportunity to observe bundles in the clinical workplace: Clinical librarians are aware of the realities of the context in which our users work, but other health sciences librarians may not spend time in clinical settings. Hospital and academic health sciences librarians will better understand their users if they observe activities in a busy hospital unit, either staying in one place to see all that goes on or shadowing individuals.

Opportunities for future research and development: Librarians who are developers may want to study examples of bundles. Bundles offer information in small doses, when it is needed, without being prompted, and in a format that calls just the right amount of attention to it. For example, cues such as placement, handwriting, color, medium, and juxtaposition to other elements are often meaningful. Information systems in clinical settings should be able to supply such cues, which require great flexibility in format. Individualization and customization are also extremely important, and they require information systems that allow clinicians to format a worksheet however they like. Tools such as SLIMPad will foster experimentation.

Opportunities to link patient care information with information resources: Librarians know about resources and about organizing them, so they are in ideal positions to develop ways to better integrate resources and digital patient information in manners that fits the constraints of the workplace. They can strive to provide information in new bundle-like ways that relate to particular clinicians and patients at particular times.

CONCLUSION

Our findings about bundles suggest that health sciences librarians may need to expand the concept of “information needs.” Forsythe offers a broader view of the concept by describing formal and informal, general and specific types of information used by physicians [5]. Studies have documented that when physicians seek answers to clinical questions, they contact colleagues rather than search the literature [6–8]. This is true despite the fact that half of their questions can be answered if they use MEDLINE [9]. As librarians, we fear clinicians may not value the literature, may not know what resources are available, or may not want to use a computer. Our research indicates, however, that there simply is no time, no matter what value one places on “the evidence.” Bundles teach us that information needs to be selected and that less is more: bundles are truly reductionist. Organizing the right amount of information, in the right format, and in a flexible way that can be used by individuals offers a challenge to medical librarians involved in research, in decision making, and in practice.

Footnotes

* This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant NSF 9817492 as part of the Digital Libraries Initiative, Phase II, sponsored by the National Science Foundation, Defense Advanced Projects Agency, National Library of Medicine, Library of Congress, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and National Endowment for the Humanities, and by National Library of Medicine award LM06942-01.

† Examples may be viewed at http://www.cse.ogi.edu/footprints/.

REFERENCES

- Gorman PN, Ash JS, Lavelle M, Lyman J, Delcambre L, Maier D.. Bundles in the wild: managing information to solve problems and maintain situation awareness. Library Trends. 2000;49(2):266–89. [Google Scholar]

- Delcambre L, Maier D, Bowers S, Deng L, Weaver M, Gorman P, Ash J, and Lavelle M. Bundles in captivity: an application of superimposed information. Accepted for presentation at the 17th International Conference on Data Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany, April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Florance V. Clinical extracts of biomedical literature for patient-centered problem solving. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996 Jul. 84(3):375–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist: a new health profession? Ann Int Med. 2000 Jun. 132(12):996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe DE, Buchanan EG, Osheroff JA, and Miller RA. Expanding the concept of medical information: an observational study of physicians' information needs. Computers and Biomedical Research. 1992 Apr. 25(2):181–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995 Apr–Jun. 15(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct. 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly DP, Rich EC, Curley SP, and Kelly JT. Knowledge resource preferences of family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1990 Mar. 30(3):353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Ash J, and Wykoff L. Can primary care physicians' questions be answered using the medical journal literature? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr. 82(2):140–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]