INTRODUCTION

The objective of the Catalogue et Index des Sites Médicaux Francophones (CISMeF) [1, 2] is to describe and index the main French-language health resources to assist health professionals in their search for electronic information available on the Internet. CISMeF is a project initiated by the Rouen University Hospital (RUH).* CISMeF began in February 1995 with the creation of the RUH's Website. In December 2000, the number of indexed resources totaled more than 9,700, with an average of fifty-one new sites added each week.

CISMeF uses two standard tools for organizing information: the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus from the U.S. National Library of Medicine [3] and the Dublin Core metadata format [4].

DESCRIPTION OF THE DUBLIN CORE

The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI)† is a project from the Online Computer Library Center, Inc. (OCLC), and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA). Metadata are data about data. This element set emerged from a series of international invitational workshops that have been held since 1995, at which broad consensus was reached among experts in resource description, networking, encoding standards, information retrieval, and a range of subject disciplines [5].

The DCMI is a metadata element set intended to facilitate the discovery of electronic resources [6]. Originally conceived for author-generated descriptions of Web resources, the DCMI is now used by museums, libraries, government agencies, and commercial organizations alike.

The building of an interdisciplinary, international consensus around a core element set is the central feature of the DCMI, which benefits from active participation and promotion in more than twenty countries in North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. The DCMI is intended to be used by non-catalogers as well as resource description specialists [7].

USING THE DUBLIN CORE METADATA INITIATIVE (DCMI) IN CATALOGUE ET INDEX DES SITES MEDICAUX FRANCOPHONES (CISMeF) -- EXAMPLE AND FIGURES

The fifteen Dublin Core elements are optional and repeatable. Resources included in CISMeF are described by eleven of the fifteen items taken from the DCMI.‡ These are: author or creator, date, description, format, identifier, language, publisher, resource type, rights, subject and keywords, and title. CISMeF does not use the four other DCMI items: contributor, coverage, relation, and source.

To capture more information, another standard element set has been developed locally to meet specific search and retrieval needs. The following eight fields are added in the data and metadata and are specific to CISMeF: institution, city, province or state, country, target or audience, type of access, cost, and sponsorship. The DCMI is used in CISMeF both as metadata and as data format.

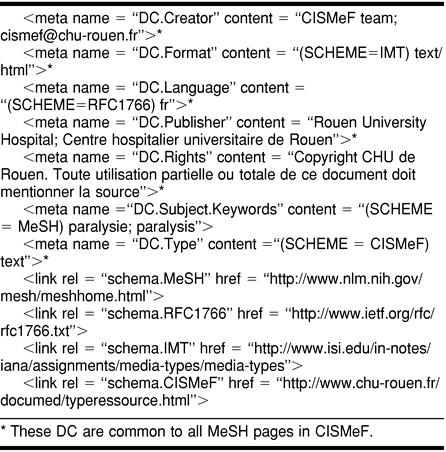

From 1995 to 1999, CISMeF used only static hypertext markup language (HTML). As CISMeF uses MeSH to index resources, every HTML page is based on a MeSH term. In December 2000, CISMeF used 3,019 MeSH terms (15% of the MeSH thesaurus). Figure 1 shows the Dublin Core elements used in the metadata of each CISMeF MeSH page, using paralysis as an example. These elements are manually written and updated by the CISMeF team.

Figure 1.

Dublin Core metadata elements used in a CISMeF MeSH page

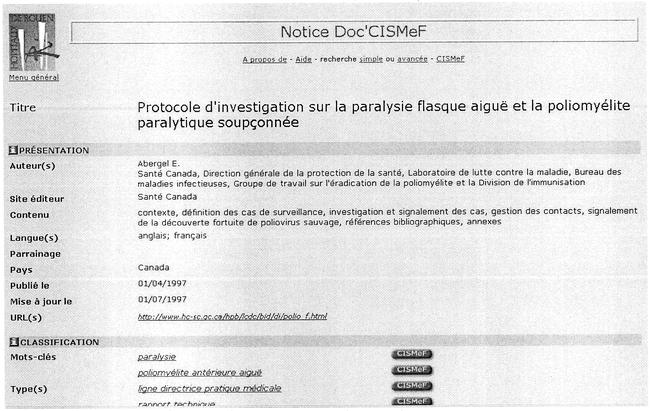

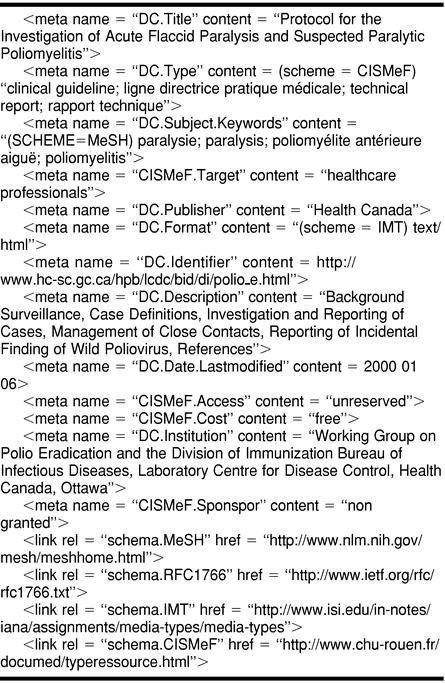

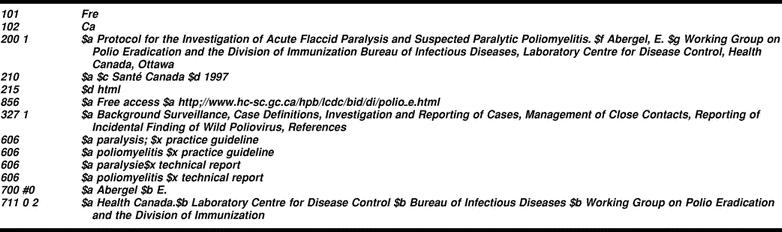

Since 2000, CISMeF has also used automatic HTML to generate one HTML page for every indexed resource (Figure 2). Figure 3 gives the Dublin Core and the CISMeF elements used in each CISMeF resource page. These elements are automatically written from the CISMeF database. Figure 4 shows an example of a description of a document indexed in CISMeF.

Figure 2.

Example of a CISMeF resource page

Figure 3.

Dublin Core metadata elements used in a CISMeF resource page (in English)

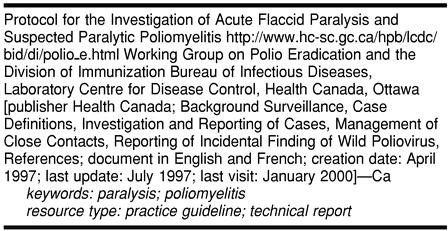

Figure 4.

Example of a description of a document indexed in CISMeF

DISCUSSION

The Internet facilitates communication between health professionals and the general public and improves information access. However, only a minority of medical resources available on the Internet contain accurate information. Several tools have been developed to assist in the retrieval of health information on the Internet. The tools are categorized as follows:

level 1: search engine, general or more specialized searches, such as MedHunt (Switzerland).§

level 2: catalogue and index without thesaurus, such as Medical Matrix (United States), MedWebPlus (United States), and HealthWeb (United States).**

level 3: catalogue and index with a thesaurus such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) metathesaurus [8] or MeSH thesaurus. The latter thesaurus is used in the following health catalogues: the Karolinska Institute's Diseases, Disorders and Related Topics (Sweden); CliniWeb International (United States) [9] from the Oregon Health Sciences University (United States); OMNI (United Kingdom) [10]; and the Health on the Net Foundation (Switzerland) [11].††

level 4: catalogue and index with thesaurus, metadata, and description of sites. CISMeF and HealthInsite (Australia)‡‡ now use level 4.

OMNI indexes approximately 4,500 resources, mostly from the United Kingdom; CISMeF about 9,700, mostly from France; MedHunt and HON approximately 40,000. OMNI and MedWebPlus use the UMLS metathesaurus to provide a conceptual network for the subject headings.

OMNI, HON, and CliniWeb have also developed structured databaseses (dynamic HTML) that permit better searches. HealthInsite and CISMeF use the Dublin Core metadata format, which is expected to become the dominant metadata format for Internet resource description.

CISMeF uses different DCMI fields, depending on whether the “browse” option (CISMeF MeSH page, Figure 1) or “search” strategy (CISMeF resource page, Figure 2) has been chosen by the end user. The choice of the Dublin Core was prompted by its institutional origin and its recognition in the academic world. Several other health sites are now using the Dublin Core: the Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, the Better Health Channel, the National Health and Medical Research Council, the World Health Organization (WHO), and, more recently, the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM).§§

The use of metadata is one main criterion in assessing the quality of health information on the Internet [12]. In order to use metadata, information must be structured. The quality of metadata description reflects the quality of online information.

Owing to its international support and rapid acceptance as a means of resource description by many communities, the DCMI has emerged as the most important standard for the simple description of electronic information resources [13]. The DCMI provides an economical alternative to more elaborate description models such as full machine-readable cataloging (MARC) [14]. DCMI is likely to become important to libraries as an alternative to full bibliographic cataloguing for Internet-based resources [15]. Table 1 illustrates this point by giving the MARC equivalent of the Dublin Core metadata elements used in a CISMeF resource page as shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

MARC equivalent of Figure 3: Dublin Core metadata elements used in a CISMeF resource page

Additionally, the DCMI includes sufficient flexibility and extensibility to encode the structure and more elaborate semantics inherent in richer description standards (e.g., the addition of eight items specific to CISMeF). The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has begun implementing an architecture for metadata for the Web. The Resource Description Framework (RDF) has been designed to support the many different metadata needs of vendors and information providers. Representatives of the DCMI effort are actively involved in the development of this infrastructure, bringing the digital library perspective to bear on this important component of the Web infrastructure [16]. Finally, promoting a commonly understood set of descriptors that helps to unify other data content standards increases the possibility of semantic interoperability across disciplines. The diversity of metadata needs on the Web requires an infrastructure that supports the coexistence of complementary, independently maintained metadata packages.

CONCLUSION

To help health care professionals and health consumers to more easily locate high-quality health information on the Internet, catalogues must use standard tools, especially metadata, to describe and index resources.

Acknowledgments

CISMeF was supported in part by the grant number 1998 06 016 from the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie in the program “French-speaking Virtual University.” The authors thank Elisabeth Essex for her advice in the editing of this manuscript and Myriam Quéré for her secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

* CISMeF may be viewed at http://www.chu-rouen.fr/cismef.

† The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Website may be viewed at http://dublincore.org.

‡ The element set may be viewed at http://dublincore.org/documents/1999/07/02/dces/.

§ MedHunt may be viewed at http://www.hon.ch.

** Medical Matrix may be viewed at www.medmatrix.org, MedWebPlus at www.medwebplus.com, and HealthWeb at healthweb.org.

†† Karolinska Institute's Diseases, Disorders and Related Topics may be viewed at www.mic.ki.se/Diseases/, CliniWeb International at www.ohsu.edu/cliniweb/, OMNI at omni.ac.uk, and Health on the Net Foundation at www.hon.ch.

‡‡ HealthInsite may be viewed at http://www.healthinsite.gov.au.

§§ The Australian Department of Health and Aged Care may be viewed at http://www.health.gov.au, the Better Health Channel at http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au, the National Health and Medical Research Council at http://www.nhmrc.health.gov.au, the

World Health Organization (WHO) at http://www.oms.ch, and the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/tsd/cataloging/metadata/.

REFERENCES

- Thirion B, Darmoni SJ. Simplified access to MeSH tree structures on CISMeF. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999 Oct. 87(4):480–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmoni SJ, Leroy JP, Baudic F, Douyère M, Piot J, and Thirion B. CISMeF: a structured health resource guide. Methods Inf Med. 2000 Mar. 39(1):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Fact sheet MEDLINE. 4 May 2000. [Web document]. The Library: Bethesda, MD. [cited 5 Jun 2000]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/medline.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel SL, Koch T. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. D-Lib Magazine December 2000. [Web document]. <http://www.dlib.org/dlib/december00/weibel/12weibel.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. [Web document]. [2 Dec 2000; cited 12 Dec 2000] <http://purl.org/DC/>. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh S. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. December 1999. [Web document]. [cited 12 Dec 2000]. <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/pubs/netnotes/notes63.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh S. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. December 1999. [Web document]. [cited 12 Dec 2000]. <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/pubs/netnotes/notes63.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. . Fact sheet UMLS Metathesaurus. [Web document]. [23 Feb 2000; cited 12 Dec 2000]. The Library: Bethesda, MD. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/umlsmeta.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh WR, Brown KE, Donohoe LC, Campbell EM, and Horacek AE. CliniWeb: managing clinical information on the World Wide Web. JAMIA. 1996 Jul–Aug. 3(4):273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman F. Organizing Medical Networked Information (OMNI). Med Inform (Lond). 1998 Jan–Mar. 23(1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer C, Baujard O, Baujard V, Aurel S, Selby M, and Appel RD. Health On the Net automated database of health and medical information. Int J Med Inf. 1997 Nov. 47(1–2). 27–9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santé Centrale. Net Scoring: criteria to assess the quality of Health Internet information. [Web document]. [29 Feb 2000; cited 12 Dec 2000]. <http://www.chu-rouen.fr/dsii/publi/netscoring.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. [Web document]. [2 Dec 2000; cited 12 Dec 2000] <http://purl.org/DC/>. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh S. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. December 1999. [Web document]. [cited 12 Dec 2000]. <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/pubs/netnotes/notes63.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. [Web document]. [2 Dec 2000; cited 12 Dec 2000] <http://purl.org/DC/>. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh S. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. December 1999. [Web document]. [cited 12 Dec 2000]. <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/pubs/netnotes/notes63.htm>. [Google Scholar]