Abstract

Objective: Classifications of diagnoses and procedures are very important for the economical as well as the quality assessment of surgical departments. They should reflect the morbidity of the patients treated and the work done. The authors investigated the fulfillment of these requirements by ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases: 9th Revision) and OPS-301, a German adaptation of the ICPM (International Classification of Procedures in Medicine), in clinical practice.

Design: A retrospective study was conducted using the data warehouse of the Surgical Center II at the Medical Faculty in Essen, Germany. The sample included 28,293 operations from the departments of general surgery, neurosurgery, and trauma surgery. Distribution of cases per ICD-9 and OPS-301 codes, aggregation through the digits of the codes, and concordance between the classifications were used as measurements. Median and range were calculated as distribution parameters. The concentration of cases per code was graphed using Lorenz curves. The most frequent codes of diagnoses were compared with the most frequent codes of surgical procedures concerning their medical information.

Results: The total number of codes used from ICD-9 and OPS-301 went up to 14 percent, depending on the surgical field. The median number of cases per code was between 2 and 4. The concentration of codes was enormous: 10 percent of the codes were used for about 70 percent of the surgical procedures. The distribution after an aggregation by digit was better with OPS-301 than with ICD-9. The views with OPS-301 and ICD-9 were quite different.

Conclusion: Statistics based on ICD-9 or OPS-301 will not properly reflect the morbidity in different surgical departments. Neither classification adequately represents the work done by surgical staff. This is because of an uneven granularity in the classifications. The results demand a replacement of the ICD-9 by an improved terminological system in surgery. The OPS-301 should be maintained and can be used at least in the medium term.

The use of coding systems for diagnoses and procedures in surgery has a long tradition.1 The advantage of classifications instead of free text is in the standardization and typing of cases, which enables analyses of data based on groups of similar patients.2 Diagnoses and surgical procedures are core elements for the definition of similar groups in surgery.3 Diagnoses include preoperative indications, postoperative evaluated causes, and complications. Surgery focuses on the operating room as the organizational unit for procedures. In addition to this clinical usage, classifications are necessary for billing and for implementing health care policies.

In Germany, the ICD-10-SGBV, an adaptation of the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases: 10th Revision), and the “Operationenschlüssel nach §301 SGB V” (OPS-301), an adaptation of the International Classification of Procedures in Medicine (ICPM), are required legislatively for the documentation of diagnoses and procedures in hospitals. The ICD-10 has been used for mortality data since 1998. Since the beginning of 2000, ICD-10-SGBV has been used instead of ICD-9 for statistics on morbidity.4 Surgical departments have to collect diagnoses for admission, transfer, discharge, and operations as well as any procedure covered by OPS-301. The data will be transmitted electronically from hospitals to health insurance companies in the future.

Diagnoses and procedures are also used for the inference of case groups, which are defined by the legislatively required classifications. It is proposed that a minimum basic data set of diagnoses, procedures and demographic characteristics will be used by health care insurances and governments to assess the quality of treatment.5 In conclusion, the legislatively required classifications are important for the economical as well as the quality assessment of surgical departments.

It is surprising, therefore, that few studies concerning the appropriateness and use of classifications in surgery have been reported. A recent medline search using the Web server of the Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) (http://www.dimdi.de) shows this lack. Including the years 1992 through 1999, the search revealed only 12 titles combining the keywords “diagnosis” and “classification” and only 3 titles combining the keywords “surgical procedures, operation” and “classification.” The retrieved publications discuss the use and concept of classifications, but none evaluates the classifications themselves.

Currently, there are two main approaches to the evaluation of terminological systems. First, a conceptual view on the structure of terminological systems is presented. This approach is usual for the scientific community (see, for example, Chute et al.6 for the United States and Rossi Mori7 for Europe) and is also used during selection processes of classifications. The second approach uses an experimental design for the comparison of classifications.8–11 Neither approach generates knowledge on the data, which emerge from the use of terminological systems in clinical practice.

A third approach is used in this paper, focusing on the quality of classifications from a practical point of view. The aim of this study is to assess classifications, in particular those of ICD-912–14 and OPS-301,15 from their output in clinical practice, to come to recommendations concerning their further refinement or replacement. In this study, three evaluation criteria were used—the reflection of morbidity (diagnoses) and productivity (procedures); the aggregation of classes to broader superclasses, providing different views for specific purposes; and the concordance between indications seen and operations performed.

Methods

Research Questions

To investigate the appropriateness and use of classifications in surgery, the following questions were asked:

Is the distribution of cases per code appropriate for a surgical department? Reflection of morbidity means that rare diseases should result in classes with a small number of cases, and common diseases should result in classes with a large number of cases. The international approach of the ICD might lead to classes that are not appropriate for surgery in Germany. A procedure classification should reflect the main area and the productivity of a surgical department.

Does the aggregation in the classification hierarchies add additional information for a surgical department? An automatically performed aggregation by digit should provide different views, depending on the required granularity.

If we look at the morbidity treated and the work done, do we obtain the same view of the department? This is specifically important because the procedures used in Germany for the comparison of hospital departments by health insurance companies include two independent statistics of diagnoses and surgical procedures.

We did not assess the congruency between the coded data and other documentation facilities, such as the paper-based patient record. Also, we did not compare the distributions between ICD-9/OPS-301 and other classifications, because the necessary experimental design was beyond our approach, which focuses on practical experience.

Data

The study is based on the computer-based patient record of the Surgical Center II at the Medical Faculty in Essen, Germany, which has been in routine use since 1989.16 The medical faculty is a teaching hospital with 1,219 beds. The Surgical Center II covers 231 beds, 15 wards, 11 operating rooms, and 3 clinics for outpatient care.

The surgical information system is a German adaptation of PCS/ADS (Patient Care System/Application Development System) from IBM, called klassik, which runs on an IBM S/390 host with a DL/1 database. Direct input of patient data for the documentation of surgical procedures is routinely performed by the surgeons themselves. A special tool, called id diacos, is used for coding. That documentation is part of the supported care process for surgical patients, which includes operation requests, scheduling, documentation, and retrieval. The surgical data include performed procedures, diagnoses, complications, times, names of staff members, and so on. The departments of neurosurgery and trauma surgery started documentation of operations on Jan 1, 1996. At that time, a new regulation required systematic documentation of some data, which motivated the departments to extend their use of the computer-based patient record.17

To ensure the completeness, correctness, and validity of the data, we established a strong quality control policy in Surgical Center II, which provides special procedures for different levels of control. Overall, the policy addresses three different levels—the level of the single physician, the level of an assistant medical doctor responsible for the data of his or her department, and a central reporting facility. Interns are able to view the documentation for each patient and get automatic reminders for their ward.

On the second level, the computer-based patient record has functionalities that make it possible for assistant medical doctors to receive information about missing or wrong data. In a previous study we showed that this level has the highest impact on the quality.18 However, the level of completeness and validity necessary for the fulfillment of legislative and medical requirements could be reached only with the introduction of a third level of quality control—specifically, central feedback and reminder. In addition, the use of a coding tool has a positive influence on data quality.19 All these methods are present in our quality control policy.

In 1997, a data warehouse was brought into routine use, which includes a subset of the data from the host. Every month, new data are exported from the computer-based patient record, transformed into a relational data model, and imported into the data warehouse. The data warehouse is realized with Microsoft Access 97. Statistical analyses are performed regularly with different indicators about the structure, processes, and outcome of treatment provided by the surgical departments.20

Classifications

According to legislative requirements, ICD-9 codes are stored for diagnoses, and codes of the ICPM German Edition (ICPM-GE) are stored for procedures. The ICPM-GE21 includes the complete OPS-301, which is legislatively required. The ICPM-GE is based on the ICPM Dutch Extension,22 an extension of the original ICPM, which was published by the World Health Organization.23 The terms stored in the data warehouse come from the internal thesaurus of the coding tool diacos, and represent a more detailed level than the standard denominations of the classifications.

The referenced numbers for ICD-9 and OPS-301 are provided by the DIMDI, which is responsible for publication, maintenance, and distribution of the German ICD as well as the OPS-301. The ICD-9 comprises 989 three-digit codes and 5,839 terminal codes, including the V axes, which indicate factors influencing health status and contact with health services. An estimation of the number of diagnosis codes in the diacos thesaurus reveals more than 40.000 terms. Within the hierarchy, an aggregation based on digits is possible only from the level of four-digit ICD-9 codes to the level of three-digit ICD-9 codes. The fifth-digit of the ICD-9 codes has not been used in Germany at all.

The OPS-301 provides 118 three-digit codes (manually calculated from the printed version15) and 6,476 terminal codes. Within the hierarchy, the OPS-301 offers an aggregation by digit from the finest level, six-digit codes, up to three-digit codes. The ICPM-GE includes 21,010 terminal codes (calculated from file ICPM.txt provided by ID GmbH).

Procedures

Codes for diagnoses and procedures were taken retrospectively from the documentation of operations within the data warehouse. The data warehouse defines an operation on a patient through the operation times of begin, incision, suture, and end. For every operation, several diagnoses and several procedure codes are possible. Thus, the number of operations is smaller than the number of diagnoses and procedures. At a minimum, one diagnosis and one procedure are necessary to define an operation. Table 1▶ shows the available number of the entities patient, operation, procedure, and diagnosis until Jun 30, 1999. The analyses exclude data from the department of general surgery before Jan 1, 1996, and include 28,293 operations.

Table 1 ▪.

Medical Entities in the Data Warehouse until Jun 30, 1999

| General Surgery | Neuro-surgery | Trauma Surgery | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 17,207 | 5,539 | 4,922 | 27,668 |

| Operations | 27,384 | 6,865 | 9,900 | 44,150 |

| Procedures | 28,933 | 8,644 | 11,280 | 48,857 |

| Diagnoses* | 49,303 | 19,114 | 24,959 | 93,376 |

| Date of first operation | 09/04/90 | 01/01/96 | 01/01/96 | – |

* Surgical and nonsurgical.

The data were described using the distribution parameters median and range. As shown in the results, the distribution is quite uneven, which makes expressions of mean and SD inappropriate. The findings are graphed using Lorenz curves. Lorenz curves represent the concentration of cases by the distance from the diagonal. The more concentrated the cases, the farther the concentration curve is from the diagonal. An equal distribution of diagnoses to ICD-9 codes or procedures to OPS-301 codes would result in a straight line.24

The English terms of the ICD-9 were obtained from a resource offered by the Internet project team of the German Association for Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology (GMDS), which is available at http://www.med.uni-muenchen.de/ibe/internet/icdsearch/homepage.html.

Results

Distribution of Cases

Table 2 ▶provides an overview of the distribution of indications with the ICD-9. The department of neurosurgery uses the lowest number of codes (n= 266) and has, at the same time, the highest range (1–1,220 codes). The median is similar between the departments, with 2, 3, or 4 diagnoses per code. The two most frequent codes for each department are listed in Table 3▶. The unspecific codes in trauma surgery result from the use of the ICPM-GE for nonsurgical intervention procedures within the facilities provided by the computer-based patient record for the documentation of operations. The ICPM-GE includes many nonsurgical procedures, unlike the legislatively required OPS-301. Therefore, the diagnoses for surgical procedures that have an ICPM-GE code beginning with 5, indicating the chapter concerned with operations, are also shown in Table 2▶. Now the two most frequent ICD-9 codes of the department of trauma surgery are 813.0 “Fracture of upper end of radius & ulna, closed” and 823.0 “Fracture of upper end of tibia & fibula, closed.”

Table 2 ▪.

Distribution of Diagnoses for Operations with Terminal ICD-9 Codes

| Trauma Surgery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Surgery | Neuro- surgery | Total | ICPM GE 5* | |

| Surgical procedures | 12,708 | 8,644 | 11,280 | 8,648 |

| Diagnoses | 11,868 | 6,910 | 10,099 | 7,627 |

| Different ICD-9 codes | 790 | 266 | 539 | 475 |

| Surgical procedures per ICD-9 code: | ||||

| Median | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 460 | 1,220 | 471 | 296 |

*The leading 5 of ICPM-GE indicates the chapter on operations.

Table 3 ▪.

Most Frequent ICD-9 Codes

| Code | Denomination | No. of Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgery | 585 | Chronic renal failure | 460 |

| 174.9 | Malignant neoplasm of breast (female), unspecified | 445 | |

| Neurosurgery | 722.1 | Displacement of thoracic or lumbar intervertebral disc without myelopathy | 1,220 |

| 331.4 | Obstructive hydrocephalus | 699 | |

| Trauma surgery | 486 | Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 471 |

| 959.9 | Other and unspecified injury to unspecified site | 464 |

To get a notion of the effect of the ICD-10, we analyzed the level of thesaurus terms provided by diacos. The number of terms used is about 2.5 times higher than the number of codes used. At the same time, the median decreases to 2 for all departments and the maximum decreases between 0.7 percent (trauma surgery) and 28 percent (neurosurgery).

These results correspond to a further refinement, especially in rare codes. The following ICD-9 codes are stored with the highest number of different terms from the thesaurus—in general surgery, code 239.0 “Neoplasm of unspecified nature of digestive system” with 25 terms; in neurosurgery, code 431 “Intracerebral hemorrhage” with 15 terms; and in trauma surgery, code 715.3 “Osteoarthrosis, localized, not specified whether primary or secondary” with 27 terms. The thesaurus refines these ICD-9 codes through a specific localization. This localization is also introduced by the respective ICD-10 classes.

The investigation of ICPM-GE and OPS-301 was performed like that of ICD-9. Table 4▶ presents an overview. The median is 2 or 3, and the maximum is between 364 and 1,784 surgical procedures per ICPM-GE code. The refinement of the OPS-301 through the ICPM-GE is more relevant for rare codes, as becomes obvious in the falling median and the nearly unchanged range. As with the analysis of diagnoses, the data show that the documentation of operations is also used for the documentation of nonsurgical interventional procedures in trauma surgery, indicated by a severe decrease in the number of codes used from the level of ICPM-GE to OPS-301. The most frequently used OPS-301-codes are listed in Table 5▶. A more detailed level is available in the ICPM-GE for the codes 5-399.5, 5-900.0 and 5-787.y.

Table 4 ▪.

Distribution of Surgical Procedures with Terminal Codes of ICPM-GE and OPS-301

| General Surgery |

Neurosurgery |

Trauma Surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICPM-GE | OPS-301 | ICPM-GE | OPS-301 | ICPM-GE | OPS-301 | |

| Surgical procedures: | 12,708 | 12,257 | 8,644 | 8,580 | 11,280 | 8,942 |

| Different codes: | 1,407 | 860 | 534 | 326 | 1,686 | 791 |

| Surgical procedures per code: | ||||||

| Median | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 1,784 | 1,922 | 993 | 993 | 364 | 628 |

Table 5 ▪.

Most Frequently Used OPS-301 Codes

| Code | Denomination | No. of Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgery: | 5-399.5 | Implementation of a peripheral port | 1992 |

| 5-541.0 | Explorative laparotomy | 403 | |

| Neurosurgery: | 5-831.0 | Excision of a disc | 993 |

| 5-980 | Microsurgical operation | 564 | |

| Trauma surgery: | 5-900.0 | Seam of skin | 628 |

| 5-787.y | Removal of osteosynthesis material, not otherwise specified | 298 |

Aggregation by Digit

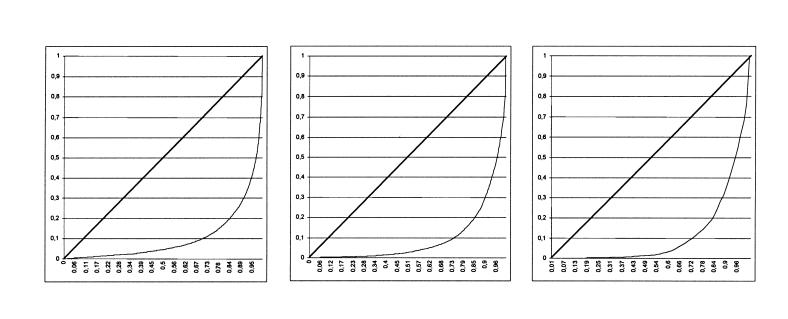

The aggregation results from four-digit ICD-9 to three-digit ICD-9 codes are presented in Table 6▶. As with the analysis of the terminal ICD-9 code, the department of neurosurgery has a remarkable maximum of 1,720 diagnoses per code but a median that increases by only 1. In general surgery, there is a significant aggregation from a median of 3 to a median of 8, keeping the maximum nearly unchanged. Nevertheless the Lorenz curves (Figure 1▶) show that the changes do not affect the enormous concentration of the distribution parameters between four- and three-digit ICD-9 codes. The number of codes decreased by half. About 14 percent (neurosurgery) to 35 percent (general surgery) of all three-digit ICD-9 codes are used.

Table 6 ▪.

Distribution of Diagnoses for Operations with Three-digit ICD-9 Codes

| Trauma Surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeneralSurgery | Neuro- surgery | Total | ICPM-GE 5* | |

| Different three-digit ICD-9 codes: | 349 | 140 | 243 | 207 |

| Surgical procedures per three-digit ICD-9 code: | ||||

| Median | 8 | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 460 | 1,720 | 710 | 574 |

*The leading 5 of ICPM-GE indicates the chapter on operations.

Figure 1.

Lorenz curves for the distribution of diagnoses with four-digit ICD-9-codes (left) and three-digit ICD-9-codes (right) from general surgery. The horizontal axes show the cumulative relative frequency of codes and the vertical axes the cumulative relative frequency of diagnoses. As reference the straight line demonstrates an equal distribution, in which each diagnosis code has the same frequency in the sample.

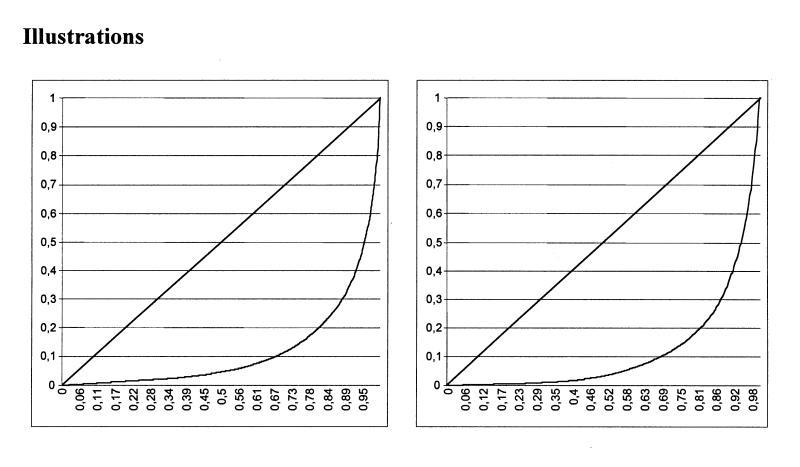

The patterns of aggregation with the OPS-301 are very interesting. Table 7▶ shows that the number of codes is reduced similarly for all surgical fields. Compared with the 118 three-digit codes of the OPS-301, between 28 and 58 percent are used in neurosurgery and general surgery, respectively. First, the median increases enormously by aggregation on the level of four-digit OPS-301 codes. This corresponds to a symmetric aggregation of rare and frequent codes. However, on the level of three-digit OPS-301 codes, the median decreases again. This effect could be interpreted by a further indication of rare surgical procedures. Nevertheless, the Lorenz curves show a strong concentration on all levels. Ninety percent of the surgical procedures are classified by about 30 percent of the codes, and 10 percent of the codes are used for about 70 percent of the surgical procedures (Figure 2▶).

Table 7▪.

Distribution of Surgical Procedures with Four-digit and Three-digit OPS-301 Codes

| General Surgery |

Neurosurgery |

Trauma Surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-digit | Three-digit | Four-digit | Three-digit | Four-digit | Three-digit | |

| Different OPS-301-codes: | 267 | 68 | 96 | 33 | 169 | 54 |

| Surgical procedures per code: | ||||||

| Median | 7 | 17 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 4.5 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 2,386 | 2,876 | 1,666 | 2,425 | 1,003 | 2,058 |

Figure 2.

Lorenz curves for the distribution of procedures with terminal OPS-301 codes (left), four-digit OPS-301-codes (middle), and three-digit OPS-301-codes (right) from general surgery. The horizontal axes show the cumulative relative frequency of codes, and the vertical axes the cumulative relative frequency of procedures. As a reference, the straight line indicates an equal distribution, in which each procedure code has the same frequency in the sample.

The aggregation is consistent within one hierarchy concerning general surgery. The most frequently used code constantly indicates surgical procedures performed on blood vessels. In neurosurgery, the aggregation changes the hierarchy from excision of disc on the four-digit level to incision and excision of skull and brain on the three-digit level. In trauma surgery, it changes between all levels, coming from seam of skin to removal of osteosynthesis material (four-digit) and reposition of fractures (three-digit). Normally, the OPS-301 requires the classification of one operation with a single code. For some situations, a combination of codes is required—for example, to indicate the approach in neurosurgery. This strategy is well implemented in general surgery, with 92 percent of operations having a single code, and in trauma surgery, with 90 percent of operations having a single code. In neurosurgery, a single code is used in only 86 percent of the operations, and more than three codes are used in 3 percent.

Concordance Between Indications and Surgical Procedures

In general surgery, 40 percent of the operations have indications from oncology (chapter II of ICD-9). Does this mean that oncologic surgery is the main field of interest? The analysis of the procedures classified by the ICPM-GE reveals that the three most frequent codes represent the implantation of a peripheral port, an explorative laparotomy, and the removal of a peripheral port. Thus, the high number of indications from oncology is caused by diagnostic or assistant surgical procedures and not by curative approaches.

In trauma surgery, we found “Fracture of upper end of radius & ulna, closed” (n= 296) and “Fracture of upper end of tibia & fibula, closed” (n= 271) the most frequent indications. However, the most frequent surgical procedures classified with the ICPM-GE were seam of skin head and neck (n= 246) and seam of skin hand (n= 211). A detailed analysis of seam of skin head and neck reveals that this surgical procedure was performed on the basis of 11 different indications. The most frequent indication, “Other & unspecified open wound of head without mention of complication,” occurs only 159 times, which is substantially less than fractures of radius/ulna, with 246 cases. “Fracture of upper end of radius & ulna, closed” was found with 80 different procedures. Among these, the most frequent procedure occurs only 91 times.

Discussion

The ICD-9 has, historically, developed over more than 100 years, extending its application from mortality to both mortality and morbidity.25 The ICD-9 is used increasingly for health care economics and health care reporting. The parts “External causes of morbidity and mortality” and “Factors influencing health status and contact with health services,” which were additional structures (E- and V-classifications) in ICD-9, were included as chapters XX and XXI in ICD-10.

In contrast, the results presented in this paper concerning the use of ICD-9 in surgery are disappointing. The ICD-9 does not reflect the morbidity in general surgery, neurosurgery, and trauma surgery. The department of general surgery uses about 14 percent of the terminal codes from the ICD-9 as operation indications. The number of cases per code is very low, with a median between 2 and 4. On the one hand, there are a high number of classes with small coverage and, on the other hand, some classes with a very high number of cases. We conclude that the ICD-9 does not support the establishment of a useful surgical documentation. The question that arises is whether the ICD-10 will solve the problems. Looking at the diacos thesaurus, it can be estimated that the ICD-10 will further strengthen this situation by tackling smaller and broader classes in the same way.

The OPS-301 has been used since 1996. It is the first legislatively required classification for surgical procedures in German hospitals. The results with the OPS-301 are not homogenous. As with the ICD-9, the highest number of codes is used by general surgery and the lowest number by neurosurgery. The median is between 2 and 4. The uneven granularity of the OPS-301 becomes apparent in general surgery with the combination of the lowest median of 2 and the highest range of 1 to 1,922. In comparison with ICD-9 and ICD-10, the ICPM-GE provides more details but does not improve the distribution patterns concerning surgery.

The ability to aggregate ICD-9 classes to broader superclasses is different among the medical fields. In general surgery, small classes are grouped, as indicated by an increasing median from 2 to 8 cases per class. There is no significant effect in neurosurgery or trauma surgery. Thus we have to state that the ability to aggregate is not very good. The results concerning aggregation are slightly better with the OPS-301 than with the ICD-9. Aggregation from five-digit codes to three-digit codes raises the median from 2 to 17 cases per class in general surgery and, from five-digit codes to four-digit codes, from 4 to 11 in neurosurgery and from 3 to 8 in trauma surgery. Thus, it is possible to aggregate classes to broader superclasses with the OPS-301.

The results further reveal shortcomings in the concordance between ICD-9 and OPS-301. Statistics using one classification alone will lead to wrong conclusions concerning the work of a surgical department.

Conclusion

This study shows that neither ICD-9 nor OPS-301 are satisfactory for surgical documentation of diagnoses and procedures. The shortcomings of the OPS-301 are obvious, but overall the OPS-301 provides better results in the domain of procedures than the ICD-9 provides in the domain of diagnoses. Therefore, we recommend that the OPS-301 be maintained in the medium term, until it can be replaced.

It can be argued from the results that the ICD-9 as well as the currently used ICD-10 should be replaced for the classification of morbidity. This will follow the strategy concerning reimbursement, in which the ICD is more or less adapted to the requirements at hand (for example, ICD-9-CM26 in the United States and ICD-10-SGBV27 in Germany). For clinical purposes, an adaptation seems not to be sufficient, bearing in mind the problems, which are described for the ICD-928 and which were newly introduced with the ICD-10.29 There should be a new clinical classification, which covers the morbidity and productivity of surgery as well as of other medical fields. The coverage should be at least national. The differences in the problems in health care—as, for example, between industrial and developing nations—might be too fundamental to use the same clinical classification in surgery worldwide. A new clinical classification of diseases has to be used in parallel with the ICD, which is mandatory for the documentation of mortality data. Basic requirements for any terminological system in surgery are the reflection of surgical work and the automatic aggregation of classes for different views.

The measurements for the quality of terminological systems have to be adapted to the phase of use. Campbell et al.30 analyzed completeness, taxonomy, mapping, definitions, and clarity of clinical coding schemes, using the title “phase II evaluation”and referring to a study on content coverage as phase I evaluation. We would suggest introducing our approach as phase IV evaluation, in comparison with the phases distinguished for the trials of medicinal products.31 Phase IV evaluation would focus on measurements of the practical use of terminological systems. Phase III evaluation could be the controlled introduction of terminological systems in a real-world setting.

The use by surgeons of terminological systems like classifications and nomenclatures will be necessary until a complete electronic patient record, including all data for individual patients, becomes a reality.32,33 The selection, development, and further maintenance of these terminological systems should take into account the experiences of routine use. Better classifications are needed in surgery to properly reflect the morbidity of patients and the work done by health professionals. This does not necessarily mean a more detailed classification, as our study revealed that the granularity of the classifications used in Germany is in some areas too high. It will be essential to address the possibility of defining broad classes, as they are necessary for economy, quality management, and research.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the technical staff of the Institute for Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology—Gerald Hoch, Olga Kolke, Ernst Pitsch, Helmut Schneider, and Wiltrud Rademacher.

References

- 1.Goegler E, Ott G. Diagnostic and therapeutic codes in surgery. Der Chirurg. 1969;40:258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingenerf J, Giere W. Concept-oriented standardization and statistics-oriented classification: continuing the classification versus nomenclature controversy. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37:527–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasteiger I, Hasek P, Herwig H. Chirurgische Basisdokumentation und Qualitätssicherung. In: Kunath H, Lochmann U, Hrsg. Klassifikation als Voraussetzung für Qualitätssicherung: Grundlagen und Anwendung. Landsberg/Lech: ecomed, 1993:23–7.

- 4.Graubner B, Brenner G. German adaptations of ICD-10. In: Kokol P, Zupan B, Stare J, Premik M, Engelbrecht R, eds. Medical Informatics Europe ‘99. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: IOS, 1999:912–7. [PubMed]

- 5.Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell JR. A framework for comprehensive health terminology systems in the United States: development guidelines, criteria for selection, and public policy implications. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:503–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi Mori A. Coding systems and controlled vocabularies for hospital information systems. Int J Biomed Comput. 1995;39:93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell KE, Oliver DE, Campbell JR. The content coverage of clinical classifications. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausam RR, Hahn AW. Representation of clinical problem assessment phrases in U.S. family practice using Read version 3.1 terms: a preliminary study. Proc 19th Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:426–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lange LL. Representation of everyday clinical nursing language in UMLS and SNOMED. AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:140–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mullins HC, Scanland PM, Collins D, et al. The efficacy of SNOMED, Read codes, and UMLS in coding ambulatory family practice clinical records. AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:135–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Internationale Klassifikation der Krankheiten, Verletzungen und Todesursachen (ICD). Band 1 Teil A. Systematisches Verzeichnis der Dreistelligen Allgemeine Systematik und der Vierstelligen Ausführlichen Systematik—Stand 1.1.1993. Cologne, Germany: Kohlhammer, 1986.

- 13.Internationale Klassifikation der Krankheiten, Verletzungen und Todesursachen (ICD). Band I Teil B. Zusätzliche Systematiken und Klassifizierungsregeln— Stand 1.1.1993. Cologne, Germany: Kohlhammer, 1987.

- 14.Internationale Klassifikation der Krankheiten, Verletzungen und Todesursachen (ICD). Band II. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis 4. Auflage—Stand 1.1.1993. Cologne, Germany: Kohlhammer, 1988.

- 15.Deutsches Institut für medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI), Hrsg. Operationenschlüssel nach §301 SGB V—Internationale Klassifikation der Prozeduren in der Medizin (OPS-301), Version 1.1, Stand 19. Feb 1996. Cologne, Germany.

- 16.Albrecht KH, Stausberg J, Eigler FW. Five-year experience with a hospital information system. In: Dohrmann P, Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B (eds). Surgical Efficiacy and Economy (SEE). Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme, 1997:202.

- 17.Stausberg J, Albrecht KH, Pitsch E, Schneider H. Integration of new legislative regulations into a surgical patient record. In: Hoffmann U, Ahrens K, Fleischer S (eds). The Future of Health Information Management. 12th International Health Records Congress. Munich, Germany: MMV, 1996:85–91.

- 18.Stausberg J. Evaluation of quality control methods for medical documentation. In: Pappas C, Maglaveras N, Scherrer JR (eds). Medical Informatics Europe ‘97. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: IOS, 1997:864–8. [PubMed]

- 19.Hohnloser JH, Puerner F, Kadlec P. Coding medical concepts: a controlled experiment with a computerized coding tool. Med Inform.1996; 21:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stausberg J, Kolke O, Albrecht K. Using a computer-based patient record for quality management in surgery. MedInfo 98. 1998:80–4. [PubMed]

- 21.Kolodzig C, Thurmayr R, Diekmann F, Raskop AM, Hrsg. ICPM. Internationale Klassifikation der Prozeduren in der Medizin. Deutsche Fassung. Version 1.1. Berlin, Germany: Blackwell, 1995.

- 22.Flier FJ, Hirs WM. The challenge of an international classification of procedures in medicine. MedInfo 95. 1995:121–5. [PubMed]

- 23.World Health Organization. International Classification of Procedures in Medicine. Geneva: WHO, 1978.

- 24.Fahrmeir L, Künstler R, Pigeot I, Tutz G. Statistik. Der Weg zur Datenanalyse. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 1999.

- 25.Gersenovic M. The ICD Family of Classifications. Methods Inf Med. 1995;34:172–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Care Financing Administration. International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision: Clinical Modifications (ICD-9-CM). Rockville, Md: Health Care Financing Administration, 1989.

- 27.Deutsches Institut für medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI), Hrsg. ICD-10-SGBV Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme. 10. Revision. Band I—Systematisches Verzeichnis. Version 1.3, Stand July 1999. Berlin, Germany: SBG, 1999.

- 28.Surján G. Review: questions on validity of International Classification of Diseases–coded diagnoses. Int J Med Inform. 1999;54:77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stausberg J, Zaiss A, Fuchs J, Berke A. Using ICD-10 for case groups. In: Hasmann A, Blobel B, Dudeck J, Engelbrecht R, Gell G, Prokosch H-U (eds). Medical Infobahn for Europe. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS, 2000:359–63..

- 30.Campbell JR, Carpenter P, Sneidermann C, Cohn S, Chute CC, Warren J. Phase II evaluation of clinical coding schemes: completeness, taxonomy, mapping, definitions, and clarity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:238–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CPMP Working Party on Efficiacy of Medicinal Products. Good clinical practice for trials on medicinal products in the European Community. Final approval, Jul 11, 1990. In: Witte PU, Schenk J, Schwarz JA, Kori-Lindner C. Good Clinical Practice. Berlin, Germany: Habrich, 1995.

- 32.Cimino JJ. Coding systems in health care. Methods Inf Med. 1996;35:273–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers JE, Rector AL. Terminological systems: bridging the generation gap. AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:610–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]