Abstract

New drug discovery is facing serious challenges due to reduction in number of new drug approvals coupled with exorbitant rising cost. Advent of combinatorial chemistry provided new hope of higher success rates of new chemical entities (NCEs); however, even this scientific development has failed to improve the success rate in new drug discovery. This scenario has prompted us to come out with a novel approach of integrated drug discovery, where Ayurvedic wisdom can synergize with drug discovery from plant sources. Initial steps in new drug discovery involve identification of NCEs, which can be either sourced through chemical synthesis or can be isolated from natural products through biological activity guided fractionation. The sources of many of the new drugs and active ingredients of medicines are derived from natural products. The starting point for plant-based new drug discovery should be identification of the right candidate plants by applying Ayurvedic wisdom, traditional documented use, tribal non-documented use, and exhaustive literature search. Frequency analysis of the ingredients of the ancient documented formulations and analysis of their Ayurvedic attributes may provide an in-depth idea of the predominance of particular Ayurvedic characteristics based on which appropriate candidate plants may be selected for bioactivity-based fractionation. The integration of Ayurvedic wisdom with drug discovery also brings the need for a paradigm shift in the extraction process from sequential to parallel extraction. Bioassay-guided fractionation of the identified plant may lead to standardized extract or isolated bioactive druggable compound as the new drug. This integrated approach would lead to saving of cost and time, coupled with enhanced success rate in drug discovery.

Keywords: Ayurveda, biological activity, drug discovery, extraction, fractionation, plant

Introduction

Development of new drug is a complex, time-consuming, and expensive process. The time taken from discovery of a new drug to its reaching the clinic is approximately 12 years, involving more than 1 billion US$ of investments in today's context. Essentially, the new drug discovery involves the identification of new chemical entities (NCEs), having the required characteristic of druggability and medicinal chemistry. These NCEs can be sourced either through chemical synthesis or through isolation from natural products. Initial success stories in new drug discovery came from medicinal chemistry inventions, which led to the need of development of higher number of chemical libraries through combinatorial chemistry. This approach, however, was proven to be less effective in terms of overall success rate. The second source of NCEs for potential use as drug molecules has been the natural products. Before the advent of high throughput screening and the post genomic era, more than 80% of drug substances were purely natural products or were inspired by the molecules derived from natural sources (including semi-synthetic analogs). An analysis into the sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2007 reveals that almost half of the drugs approved since 1994 were based on natural products. During the years 2005–2007, 13 natural product related drugs were approved.[1] There are various examples of development of new drugs from the plant sources. Morphine was isolated from opium produced from cut seed pods of the poppy plant (Papaver somniferum) approximately 200 years ago. Pharmaceutical research expanded after the second world war to include massive screening of microorganisms for new antibiotics, inspired by the discovery of penicillin. Few drugs developed from natural sources have undoubtedly revolutionized medicine, like antibiotics (e.g. penicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin), antiparasitics (e.g. avermectin), antimalarials (e.g. quinine, artemisinin), lipid control agents (e.g. lovastatin and analogs), immunosuppressants for organ transplants (e.g. cyclosporine, rapamycins), and anticancer drugs (e.g. paclitaxel, irinotecan).[1]

Clinical trials are ongoing on more than 100 natural product derived drugs and at least 100 molecules/compounds are in preclinical development stage.[1] Most of these molecules in the developmental pipeline are derived from leads from plants and microbial sources. Cancer and infections are the two predominant therapeutic areas for which the drug discovery program is based on natural products, but many other therapeutic areas also get covered, such as neuro-pharmacological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, inflammation, metabolic, etc.[1] Among the different projects in various therapeutic areas, around 108 projects are based on plants. A further division of these projects indicates that 46 of them are in preclinical stage, 14 in phase I, 41 in phase II, 5 in phase III, and 2 are in pre-registration phase.[1]

In general, there are six classes of sources for NCEs. The four classes are botanical sources, fungi, bacteria, and marine sources. In addition to these four classes, modern pharmaceutical chemistry added two categories of man-made substances, i.e. synthetic chemistry and combinatorial chemistry. Of these natural sources, botanical sources are of specific importance in the context of this review. The botanical sources are known to provide the following classes of NCEs for drug discovery processes.

Bioactive compounds for direct use as drug, e.g. digoxin.

Bioactive compounds with structures which themselves may act as lead compounds for more potent compounds, e.g. paclitaxel from Taxus species.

The novel chemophore which may be converted into druggable compounds with/without chemical analoging.

Pure phytochemicals for use as marker compounds for standardization of crude plant material or extract.

Pure phytochemicals which can be used as pharmacological tools.

Herbal extracts as botanical drugs, e.g. green tea extract.

Drug Discovery from Natural Resources: Advantages and Disadvantages

Usage of botanical sources as starting point in the drug development program is associated with few specific advantages:

Mostly, the selection of a candidate species for investigations can be done on the basis of long-term use by humans (ethnomedicine). This approach is based on an assumption that the active com-pounds isolated from such plants are likely to be safer than those derived from plant species with no history of human use. At certain time point afterward, one may attempt upon synthesis of active molecule and reduce pressure on the resource. Drug development from Rauwolfia serpentina, Digitalis purpurea, etc. in the past fall under this category of approach.

Sometimes, such approaches lead to development of novel molecules derived from the source due to inherent limitations of the original molecule. For instance, podophyllin derived from Podophyllum hexandrum was faced with dose-limiting toxicities. Such limitations could be overcome to a great extent by semi-synthesis of etoposide, which continues to be used in cancer therapy today. Similar was the case with camptothecin (originally isolated from Camptotheca sp. and subsequently from Mappia sp.), which led to development of novel anticancer molecules like topotecan and irinotecan.

Natural resources as starting point has a bilateral promise of delivering the original isolate as a candidate or a semi-synthetic molecule development to overcome any inherent limitations of original molecule.

On the other hand, drug development from natural resources is also associated with certain disadvantages:

More often than not, drug discovery and eventual commercialization would pressurize the resource substantially and might lead to undesirable environmental concerns. While synthesis of active molecule could be an option, not every molecule is amenable for complete synthesis. Hence, certain degree of dependence on the lead resource would continue. For instance, anticancer molecules like etoposide, paclitaxel, docetaxel, topotecan, and irinotecan continue to depend upon highly vulnerable plant resources for obtaining the starting material since a complete synthesis is not possible. On the other hand, it is expected that some 25,000 plant species would cease to exist by the end of this century.[2]

Over a period of time, the intellectual property rights protection related to the natural products is going haywire. By and large, the leads are based upon some linkage to traditional usage. With larger number of countries becoming the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the process of accessing the basic lead resource, benefit sharing during the commercial phase, etc. became highly complex in many countries. These processes tend to impede the pace of discovery process at various phases irrespective of the concerns leading to such processes.

Druggability of Isolated Phytochemical Compounds

Challenges in the new drug development are mainly encountered from two categories: the prevailing paradigm for drug discovery in large pharmaceutical industries and technical limitations in identifying new compounds with desirable activity. Koehn and Carter[3] have enumerated the following unique features of the compounds isolated from natural products:

Greater number of chiral centers

Increased steric complexity

Higher number of oxygen atoms

Lower ratio of aromatic ring atoms to total heavy atoms

Higher number of solvated hydrogen bond donors and acceptors

Grater molecular rigidity

Broader distribution of molecular properties such as molecular mass, octanol water partition coefficient, and diversity of ring systems

These unique features of chemical entities of natural origin pose a string of challenges for medicinal chemists as they start working upon development of analogs, either to improve the absorption or to reduce the toxicity and improve upon efficacy which is often achieved by addition or deletion of selected functional groups. As per a review by Ehrman et al.,[4] different bioactive plant compounds were isolated in China from 1911 to 2000 like alkaloid, steroid, triterpene, limonoid, diterpene, sesquiterpene, monoterpene, tanin, isoflavonoid, flavonoid, polycyclic aromatic, lignan, coumarin, simple phenoloic, aliphatic, etc. Alkaloid may be distributed as 20%, flavonoids as 15%, triterpenes and simple phenolics around 10%, and remaining others below that, with limonoid being the least.

It can be safely presumed that large number of natural products, despite being biologically active and having favorable ADMET profile (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity), do not satisfy the criteria “drug likeness.” The challenge is of building a physio-chemical tuned natural products library in line with the lead generation to promote natural products to their full potential. Lipinski[5] propagated simple set of calculated property called “rule of five” basis the drug candidates reaching Phase II clinical trials. This rule is an algorithm consisting of four rules in which many of the cutoff numbers are five or multiples of five, thus originating the rule's name. To be drug-like, a candidate should have:

less than five hydrogen bond donors;

less than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors;

molecular weight of less than 500 Da; and

partition coefficient log P of less than 5.

The aim of the “rule of five” is to highlight possible bioavailability problems if two or more properties are violated. Had Lipinski's rule been applied, paclitaxel would never have become a drug. Since it does not comply with “rule of five,” a biggest challenge is to find alternative druggability criteria for the compounds of natural origin.

Therefore, the biggest challenge is to find alternative druggability criteria for the compounds of natural origin.

Selection of Candidate Plant Species for Screening

To available estimates, the total number of higher plants species (comprising angiosperms and gymnosperms) is approximately 250,000 species. Of them, only 6% have been reportedly screened for biological activity and about 15% have been screened for phytochemical activity.[6] Initial listing of the candidate species for screening of biological activity is a major task of specific importance in itself. Fabricant and Farnsworth[6] have enumerated the following approaches being used so far by researchers for this purpose.

Random approach

Two approaches have been followed for screening of the plants selected randomly for the purpose of new drug discovery.

-

a)

Screening for selected class of compounds like alkaloids, flavonoids, etc.: While this route is simple to perform, however, it is flawed in the sense that it provides no idea of the biological efficacy. However, chances of getting novel structures cannot be denied following this approach.

-

b)

Screening of randomly selected plants for selected bioassays: Central Drug Research Institute, a premier R and D organization of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research of India, followed this approach about three decades ago. They screened almost 2000 plants for biological efficacy. However, the screening did not yield any new drug. National Cancer Institute (NCI) of National Institute of Health, USA, studied about 35,000 plant species for anticancer activity, spending over two decades from 1960 to 1980. It resulted in proving two success stories, which were those of paclitaxel and camptothecin. This route, therefore, has been applied for both focused screening as well as general screening, showing some success in focused screening. If target-based bioassays are used, e.g. screening against PTP1B, chances of success would probably be more. This approach, however, needs a huge library of extracts, which very few organizations in the world are having.

Ethnopharmacology approach

The approach of ethnopharmacology essentially depends on empirical experiences related to the use of botanical drugs for the discov-ery of biologically active NCEs. This process involves the observation, description, and experimental investigation of indigenous drugs, and is based on botany, chemistry, biochem-istry, pharmacology, and many other disciplines like anthropology, archaeology, history, and linguistics.[7] This approach based on ethnomedicinal usage history has seen some success, e.g. Andrographis paniculata was used for dysentery in ethnomedicine and the compounds responsible for the activity were isolated as andrographolide. Morphine from Papaver somniferum, Berberine from Berberis aristata, and Picroside from Picrorrhiza kurroa are some examples of this approach. Some of the plants which are not selected on the basis of ethnomedical use also had some success stories, like L-Dopa from Mucuna prurita and paclitaxel from Taxus brevifolia.

Traditional system of medicine approach

Countries like India and China have a rich heritage of well-documented traditional system of medicine in vogue. Though these codified systems of medicine use largely botanical sources as medicines, however, these stand apart from ethnomedicine specifically on three accounts:

The ethnomedicinal practice is based on empirical experiences. On the other hand, these codified systems built up the empirical practices on strong conceptual foundations of human physiology as well as of pharmacology (though the tools of their investigations in those times were far different from the existing ones).

The pharmaceutical processes have been more advanced as against the use of crudely extracted juices and decoctions in ethnomedicinal practices. Due to this phenomenon, the concept of standardization was known to the system.

They are well documented and widely institutionalized. On the other hand, the ethnomedicinal practices are localized and may be largely controlled by few families in each of the community.

However, in terms of historicity, ethnomedicinal practices might be older than codified systems of medicine.

Discovery of artemisinin from Artemesia alba for malaria, guggulsterones from Commiphora mukul (for hyperlipidemia), boswellic acids from Boswellia serrata (anti-inflammatory), and bacosides from Bacopa monnieri (nootropic and memory enhancement) was based on the leads from these codified systems of medicine prevailing in China and India. However, it can be stated that such approach for selecting candidates in drug discovery programs has not been adopted much so far. Nonetheless, the approach has a distinct promise in terms of hit rates. But the distinct example for this approach has been the discovery of reserpine from Rauwolfia serpentine, which was based on the practices of Unani medicine.

Zoo-pharmacognosy approach

Observation of the behavior of the animals with a view to identify the candidate plants for new drug discovery is not a distant phenomenon. Observation of straight tails linked to cattle grazing habits in certain regions of South America led to identification of a plant Cestrum diurnum and three other plant members of family Solanaceae, which probably are the only known plant sources of the derivatives of Vitamin D3. This approach, however, needs close observation and monitoring of the behavior of animals.

Application of Ayurvedic Wisdom in Selection of Plant for its Therapeutic (e.g. Anticancer) Activity

The key objective of this review is to emphasize on the usage of traditional wisdom in selection of candidate species as against random screening or on the basis of ethnomedicinal records. The author has reviewed few published studies and classical Ayurvedic literature for anticancer drug plants as the major source for drug discovery. Basis Ayurvedic wisdom, it is possible to apply the traditional knowledge on various herbs to identify the better leads for research and development to find out good anticancer drugs. Three disease conditions described in classical Ayurvedic texts have possible correlations to the description of cancer in modern medicine, viz. Arbuda, Granthi, and Gulma. These classical descriptions in terms of etiopathogenesis, symptoms, and prognosis related to these conditions go close to the cancerous conditions in modern context. Hence, it would be logical to assume that the botanical medicines recommended for use in these three conditions would have greater potential of hit rates in drug discovery program.

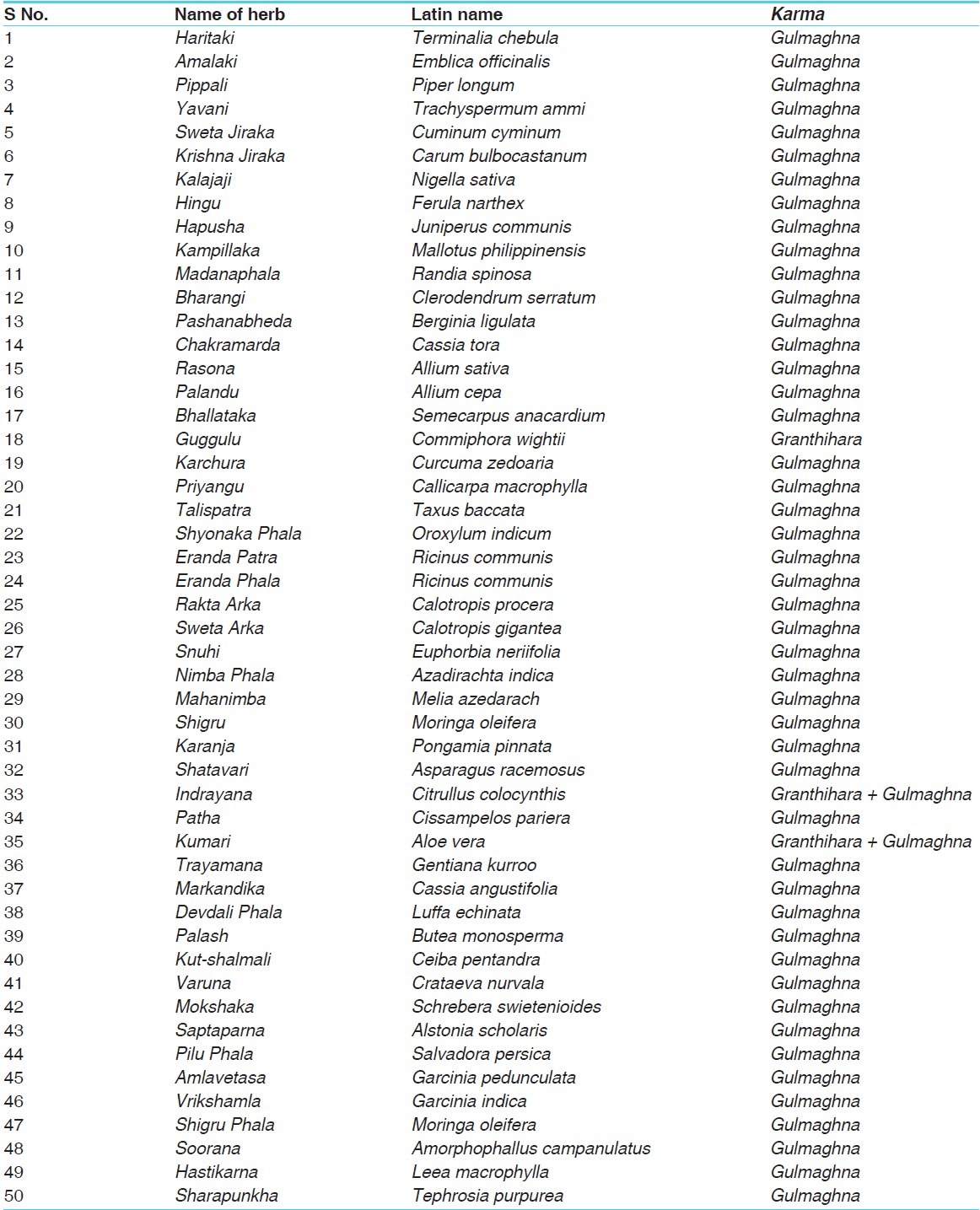

The author tried to identify the herbs from the authentic classical text, Bhavprakash,[8] traditionally employed in the treatment of cancer, and to analyze the same in terms of Rasa (taste), Guna (physico-chemical and pharmacodynamic properties), Veerya (potency), Vipaka (action after digestion and assimilative transformation), and Dosha Karma (actions of Doshas/humors). Based on this review, it has been possible to enumerate 53 herbs having acclaimed effects on Arbuda, Granthi, and Gulma. The botanical identity for three of these 53 candidates could not be established. Therefore, the rest of 50 herbs are enumerated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Properties (karma) of herbs based on Ayurvedic principles

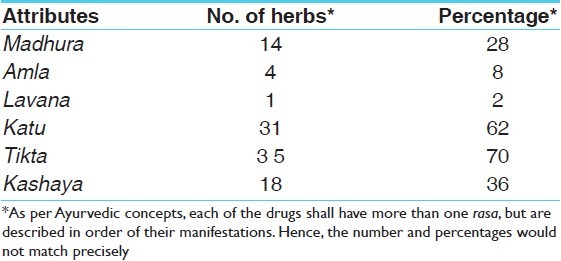

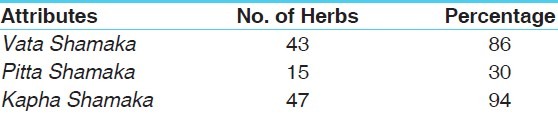

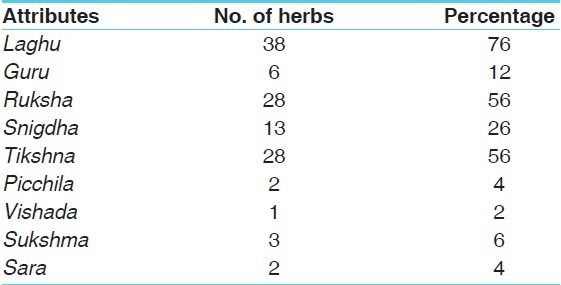

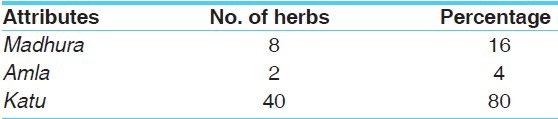

Further, these selected herbs were studied for their Ayurvedic pharmacological attributes, e.g. Rasa, Guna, Veerya, Vipaka, and Dosha Karma, as per the descriptions in Ayurvedic texts. The frequency analysis of the pharmacological attributes among these 50 herbs is provided in Tables 2–6.

Table 2.

Analysis of herbs’ basis Rasa

Table 6.

Analysis of herbs’ basis Dosha Karma

Table 3.

Analysis of herbs’ basis Guna

Table 4.

Analysis of herbs’ basis Vipaka

Table 5.

Analysis of herbs’ basis Veerya

On the basis of the classical attributes for the herbs having Arbudahara/Gulmaghna/Granthihara effects, it can be safely assumed that these herbs share some specific pharmacological traits in common. Going by the dominance analysis of these attributes and mapping of their percentage distribution, the following scenario emerges.

Predominant Rasa: Tikta and Katu

Predominant Guna: Laghu, Ruksha, and Tikshna

Predominant Vipaka: Katu

Predominant Veerya: Ushna

Predominant Dosha Karma: Kapha-Vata Shamana.

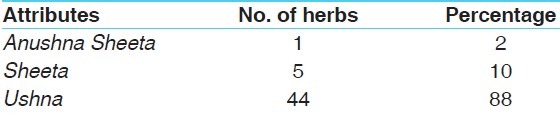

Going by Ayurvedic pharmacological concepts, an anticancer drug tends to exhibit Tikta–Katu Rasa, Laghu–Ruksha–Teekshna Gunas, Katu Vipaka, and Ushna Veerya. They are generally Kapha–Vatashamak in terms of their Dosha Karma. With a view to enhance the scope of potential anticancer species, further screening of Bhavaprakasha Nighantu was carried out. The scope of this review was to enumerate other drugs having these specific pharmacological attributes but not listed under the Gulmahara/Granthihara/Arbudhnashak Karma properties. This round of review led to enumeration of 13 more botanical species which possibly have a potential for anticancer activity. These species are: Trachyspermum ammi, Nigella sativa, Juniperus communis, Mallotus philippinensis, Commiphora wightii, Calotropis procera, Calotropis gigantea, Moringa oleifera, Citrullus colocynthis, Cassia angustifolia, Luffa echinata, Amorphophallus campanulatus, and Tephrosia purpurea.

A schematic representation of this entire review process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process for selection of potential herbs on the basis of Ayurvedic wisdom

The above scheme of review of classical Ayurvedic Nighantus was taken up to identify and shortlist potential anticancer candidates with a presumption that such methodology would enhance overall hit rate during the screening phase.

The above-mentioned approach of the author is substantiated by a similar type of study conducted earlier by Smit et al.,[9] who tried to identify the potential plant candidates for their cytostatic activity. The investigators worked to identify the candidate species on the basis of Samprapti (pathogenesis) of the disease. In this process, they zeroed down to the herbs having Pitta Vardhak, Kapha Shamak effects and Laghu, Ruksha, and Tikshna Gunas as their Ayurvedic attributes. In all, the investigators enlisted 44 species of which 14 candidates (Acorus calamus, Calotropis procera, Curcuma zedoaria, Datura metel, Mallotus philippinensis, Melia azedarach, Moringa oleifera, Plumbago zeylanica, Scindapsus officinalis, Semecarpus anacardium, Solanum indicum, Solanum xanthocarpum, Sphaeranthus indicus, and Vitex negundo) were screened against COLO 320 tumor cells, using cisplatin as control. It was observed in the study that seven species exhibited growth inhibition ranging between 83 and 100%.

Interestingly, three species, viz. Calotropis procera, Mallotus philippinensis, and Moringa oleifera find place in both the lists of anticancer herbs enumerated by Smit et al. and by the author. Two of these three common candidates (Calotropis procera and Mallotus philippinensis) exhibited cytostatic activity as reported by Smit et al. Such commonality of species indicates that it is possible to identify and shortlist the potential candidates for research purposes using the approaches having either a disease orientation (pathophysiological foundations) or drug orientation (pharmacological foundations). The concept can be relied upon from both these perspectives of Ayurveda.

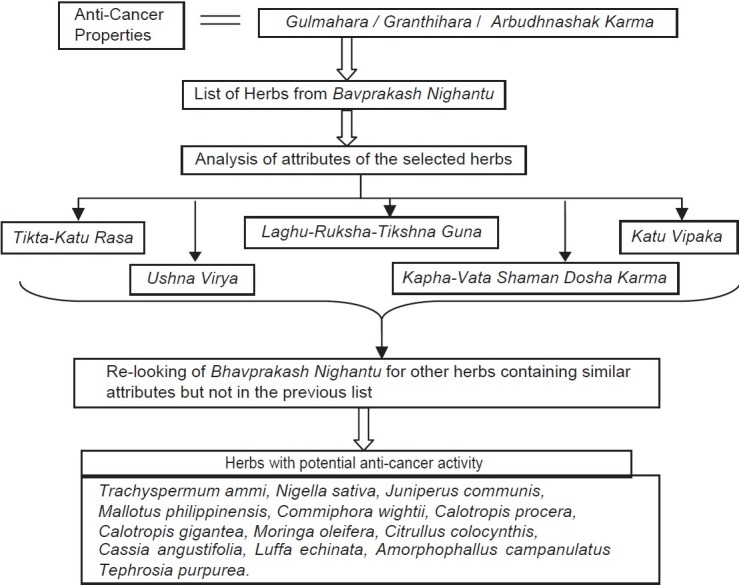

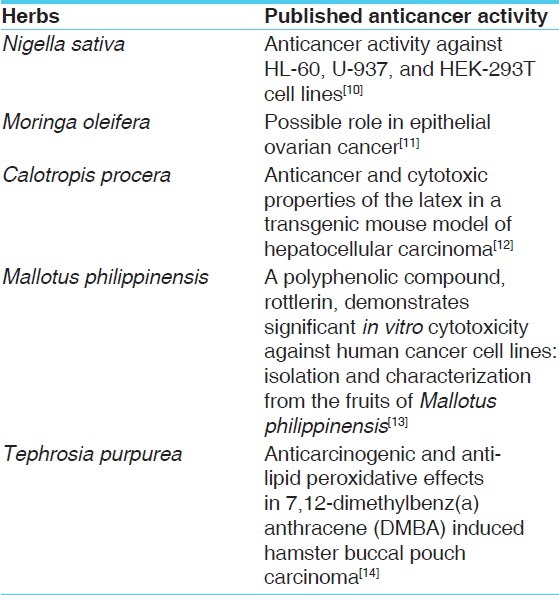

This approach gets further validated by few published reports on anticancer activity of the botanical species shortlisted through the review mechanism being suggested by the author.

As seen from the study by Smit et al. and the reports enlisted in Table 7, the hit rates in biological screening tend to improve with selection of candidates on the basis of Ayurvedic tenets of pharmacology. If this approach is widely accepted and practiced, newer horizons would open for the development of potent Ayurvedic formulations in addition to the improved success rate in development of new drugs.

Table 7.

Published anticancer activity of the some of the shortlisted herbs

Biological Activity Guided Fractionation for Compound Isolation

Biological activity guided fractionation has been the process deployed to identify the lead druggable candidate from any given phytochemical matrix. However, there is no uniformity in its methodology. Two approaches might be followed as the design of extraction for bioactive guided fractionation leading to compound isolation to act as a lead compound:

i. Parallel approach

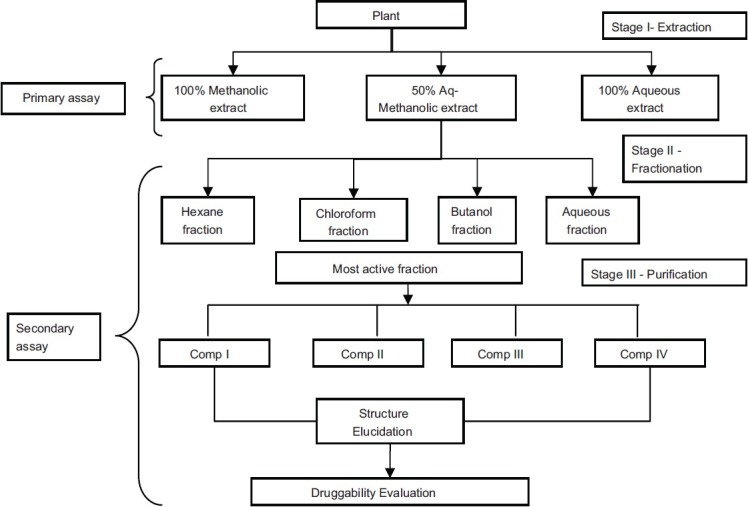

This approach may be applied when the biological activity of the plant is known by its traditional use. The objective of this approach is to isolate compounds responsible for the activity based on their biologic activity. As explained in Figure 2, in parallel extraction approach, three types of extracts are obtained, viz. 100% methanolic extract, 50% methanolic extract, and 100% aqueous extract from a crude plant. The most active fraction based on the primary screening for bioactivity is chosen for further extraction and evaluation.

Figure 2.

Parallel approach for bioassay-guided fractionation

ii. Sequential approach

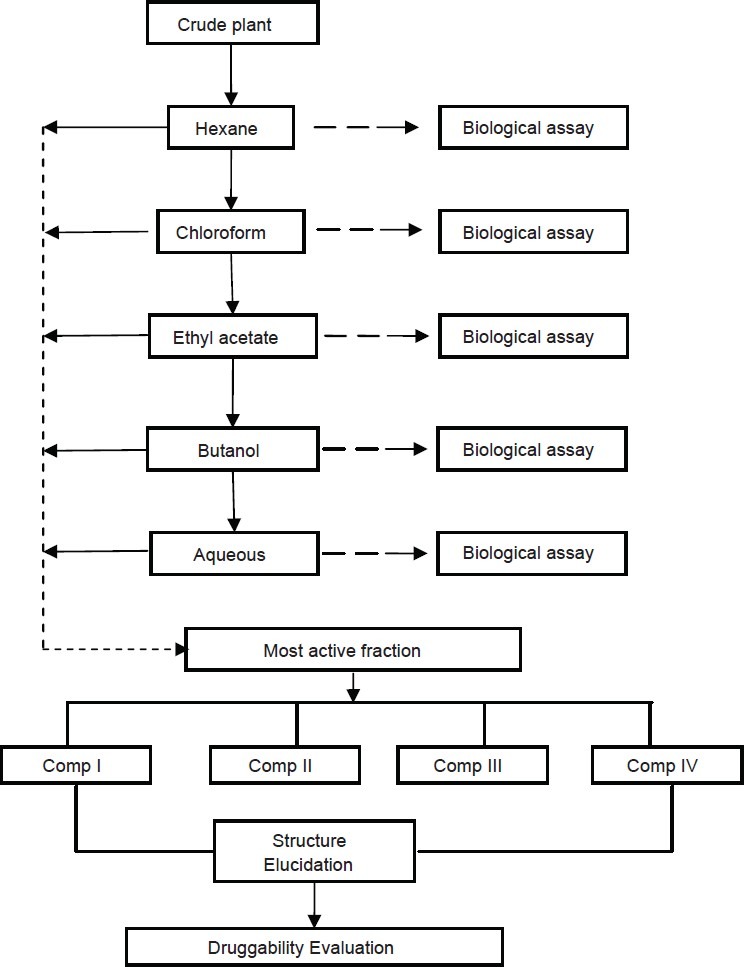

This approach may be useful when the biological activity of the subject plant is not known and random selection strategy is adopted for plants. As explained in Figure 3, extraction is done based on the polarity of the solvents and fractions are obtained in a sequential process using hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and butanol as solvents.

Figure 3.

Sequential polarity based approach of extraction

Further extraction involves purification stage where structural elucidation is done for different compounds.

Since the bioactivity is assessed at two stages, two distinct models should be chosen keeping in view the end points. The screening model for stage I should be designed to elicit the efficacy. On the other hand, the screening model for secondary screening should be designed with an orientation toward mechanism of action. For example, for discovering potential anti-diabetic molecules from a natural source, glucose uptake assay can be employed as the primary screening model. At stage II, it would be desirable to choose a secondary assay model like Glut 4, PI3 K, and IRTK, which may provide some clue for the mechanism of action. It is also desirable to include an assay for cytotoxicity so as to elicit the safety profile during secondary screening level.

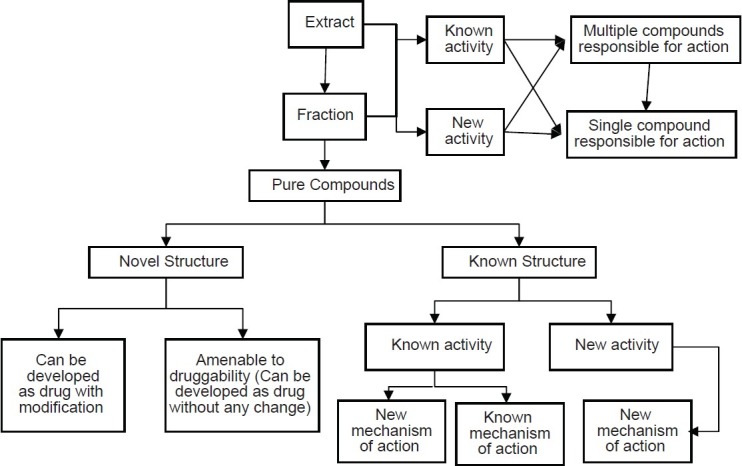

Bioactivity guided fractionation of any crude extract from natural source in any case would lead to a wide array of possible outcomes at different stages. Also, these outcomes might provide unforeseen opportunities for modulating the discovery design during subsequent stages. Figure 4 depicts the possible outcomes of a typical bioactivity guided fractionation.

Figure 4.

Array of outcome – A schematic representation

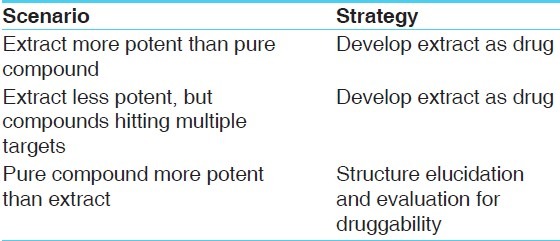

By and large, the natural products, if shortlisted on the basis of existing knowledge of usage (be it ethnomedicinal lead or from codified systems of medicine), are likely to lead to three distinct possibilities. A decision on “Go” or “No Go” can be taken based on the strategies suggested in Table 8.

Table 8.

Strategy for the Go-No Go criteria

Way Forward and Conclusions

There is a pertinent need to renew scientific enthusiasm toward natural products for inclusion in drug discovery program. One of the important concerns related to natural products has been the predictability of hit rate during various phases of drug development. Such predictability is expected to be lower in case of random selection of candidate species considering the overall complexity of botanical sources for NCEs. In order to enhance the predictability, strategic selection and shortlisting of candidate species is necessary. Documented clinical experience with botanical medicines as codified in traditional systems of medicine might simplify the issues associated with poor predictability. New functional leads picked up from the traditional knowledge and experiential database may help to reduce time, money, and toxicity, which are the three specific hurdles in the drug development.[15]

An integrative approach by combining the various discovery tools and the new discipline of integrative biology will provide the key for success in natural product drug discovery and development. Since plant selection is the major step involved, it needs a well-designed strategy.

The following scheme may be followed for appropriate plant selection:

Identification of plants: Through a tactical application of traditional wisdom, especially in the context of usage frequency. For this purpose, it is suggested to search classical treatises of Ayurveda like Bhaishajya Ratnavali and Charak Samhita, in which the formulations are enumerated for the identified therapeutic segment.

Listing of all the formulations and their herbal ingredients (metallic and herbo-mineral formulations need not be considered).

Frequency analysis of the ingredients.

Arriving at Ayurvedic hypothesis of the desired Rasa, Guna, Veerya, Vipaka, etc. to achieve particular therapeutic area, e.g. in the case of diabetes, the drug should have dominance of Katu and Tikta Rasa, Laghu Guna, Ushna Veerya, and Katu Vipaka.

Mapping of the ingredients identified above against these Ayurvedic attributes.

Shortlisting of those plant species which match both frequency analysis as well as the Ayurvedic attributes.

Once the task of enumerating potential candidates for screening is over, the extraction procedure can go by a parallel approach instead of the sequential approach as followed for randomly selected species. Rest of the investigational course shall follow the following steps:

Screening of biological activity on selective assays.

Bioassay guided fractionation of the identified plant.

Isolation and structure elucidation of the active compound.

Evaluation of chemical do-ability, druggability, and patentability.

Go or no go decisions based on safety, biological activity screening.

It is time for large-scale pharmaceutical organizations to open up the developmental strategies. In view of the increasing cost of development of new drugs, alternative approaches like development of herbal extracts hitting multiple targets as new drugs need serious consideration. Obviously, the cost of development shall be substantially lower in case of herbal extracts. Such strategy would not only enhance the chances of success in terms of providing effective and safe drugs, but also is considered to minimize the risk of post-marketing withdrawals. Such a complementary scenario shall go a long way in safeguarding the interests of both pharmaceutical industry and common man.

Acknowledgement

The first author Dr. Chandrakant Katiyar is thankful to Prof. S. S. Handa, former Consultant and Dr. Pradip Bhatnagar, Head at New Drug Discovery Research (NDDR), Ranbaxy Research Lab, Gurgaon for facilitating the new drug discovery tools exposure to him, during his tenure in 2003 – 2008.

References

- 1.Harvey AL. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahidol C, Ruchirawat S, Prawat H, Pisutjaroenpong S, Engprasert S, Chumsri P, et al. Biodiversity and natural product drug discovery. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:2065–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koehn FE, Carter GT. The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:206–20. doi: 10.1038/nrd1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrman TM, Barlow DJ, Hylands PJ. Phytochemical databases of chinese herbal constituents and bioactive plant compounds with known target specificities. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:254–63. doi: 10.1021/ci600288m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 1):69–75. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganeshan A. The impact of natural products upon modern drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misra Bhava., Sri . Bhavaprakash. In: Misra Brahmasankara, Sri, Vaisya Rupalalaji., Sri, editors. Varanasi: Published by Chaukhamba Sanskrit Santhan; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smit HF, Woerdenbag HJ, Singh RH, Meulenbeld GJ, Labadie RP, Zwaving JH. Ayurvedic herbal drugs with possible cytostatic activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;47:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01255-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel PN, Suthar M, Shah TG, Patel LJ. Anticancer activity of Nigella sativa seeds against HL-60, U-937 and HEK-293T cell line. Pharm Expt. 2010;1 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose CK. Possible role of Moringa oleifera Lam. Root in epithelial ovarian cancer. MedGenMed. 2007;9:26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choedon T, Mathan G, Arya S, Kumar VL, Kumar V. Anticancer and cytotoxic properties of the latex of Calotropis procera in a transgenic mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2517–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma V. A polyphenolic compound rottlerin demonstrates significant in vitro cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines: Isolation and characterization from the fruits of Mallotus philippinensis. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;20:190–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavitha K, Manoharan S. Anticarcinogenic and anti lipidperoxidative effects of Tephrosia purpurea (Linn) Pers. In 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) induced hamster buccal pouch carcinoma. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38:185–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patwardhan B, Vaidya AD, Chorghade M. Ayurveda and natural product drug discovery. Curr Sci. 2004;86:789–99. [Google Scholar]