Abstract

Ashwagandharishta, an Ayurvedic classical formulation, is the remedy for Apasmara (epilepsy), Murchha (syncope), Unmada (psychosis), etc. Recent studies in animal models have shown that n-3 PUFAs can raise the threshold of epileptic seizures. The indigenous medicinal plant, called Atasi (Linum usitatissimum Linn.) in Ayurveda, or flax seed, is the best plant source of omega-3 fatty acids. The present study is designed to investigate whether Ashwagandharishta and Atasi taila (flax seed oil) protect against maximal electroshock (MES) seizures in albino rats. Further, a possible protective role of flax seed oil as an adjuvant to Ashwagandharishta in its anticonvulsant activity has also been evaluated in the study. MES seizures were induced for rats and seizure severity was assessed by the duration of hind limb extensor phase. Phenytoin was used as the standard antiepileptic drug for comparison. Both flax seed oil and Ashwagandharishta significantly decreased convulsion phase. Pre-treatment with flax seed oil exhibited significant anticonvulsant activity by decreasing the duration of tonic extensor phase. Contrary to the expectations, pre-treatment with flax seed oil as an adjuvant to Ashwagandharishta failed to decrease the tonic extensor phase; however, it significantly decreased the flexion phase (P < 0.001) and duration of the convulsions (P < 0.05). Both the drugs exhibited an excellent anti-post-ictal depression effect and complete protection against mortality.

Keywords: Antiepileptic, Ashwagandharishta, flax seed oil, maximal electroshock seizure, omega-3 fatty acid

Introduction

Epilepsy is a neuropsychological disorder, which occurs due to over discharge of neurotransmitter substance.[1] Epilepsy, anxiety, and depression are all common disorders. It is therefore not surprising that the conditions coexist in a significant number of patients. Indeed, some authors estimate the lifetime prevalence of depression in association with epilepsy to be as high as 55%.[2] Despite this, there has been remarkably little research into the mechanism of depression and anxiety in epilepsy, and even less on its treatment.[3] There are number of drugs available for the treatment of epilepsy in modern therapy. But the major disadvantage being faced is their side effects. One patient out of three is resistant to antiepileptic drug;[1] thus, there is a need for new drugs which have least side effects and minimum interaction and provide more effectiveness.

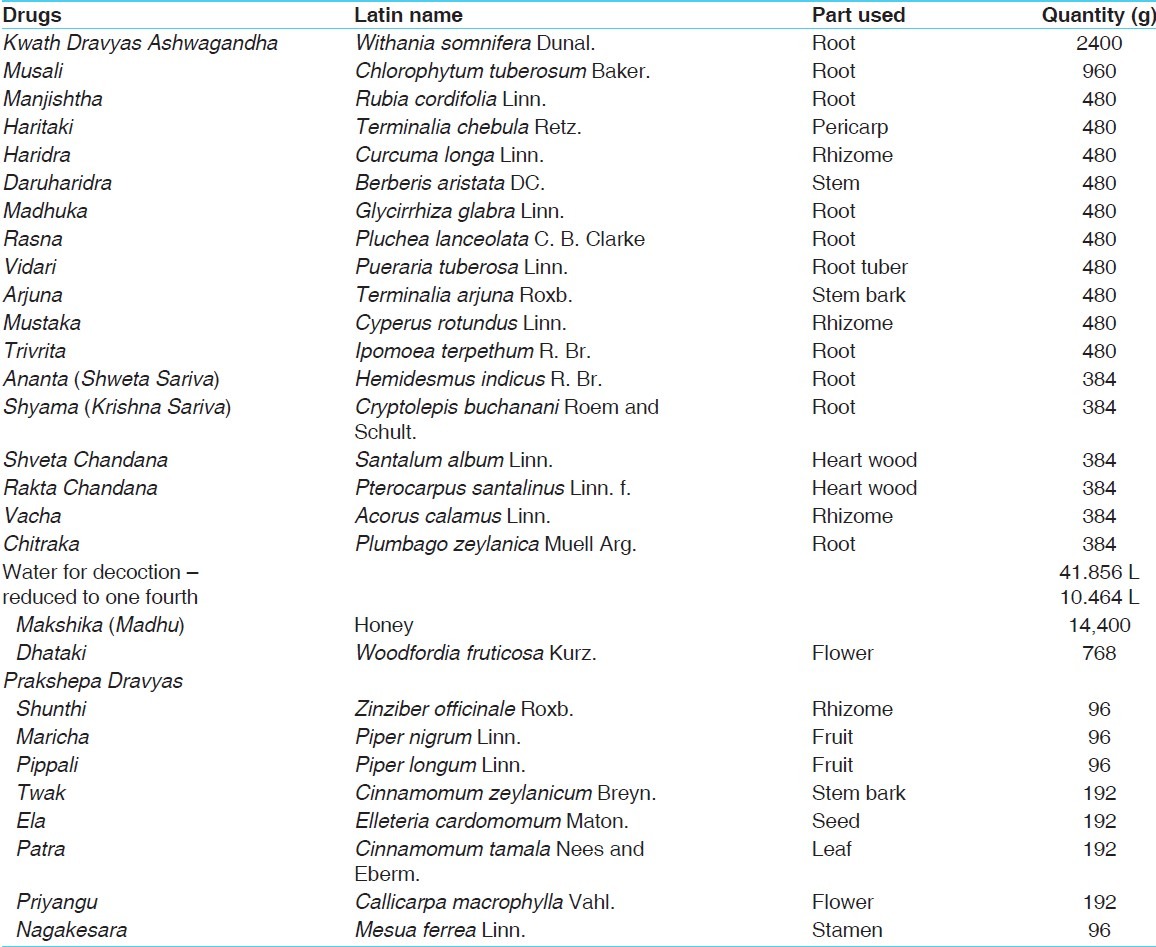

Ashwagandharishta, an Ayurvedic classical formulation, is the remedy for Apasmara (epilepsy), Shosha (tuberculosis), Murchha (syncope), Unmada (psychosis), Mandagni (poor digestive power), etc.[4] Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera D.), a main ingredient of Ashwagandharishta [Table 1], has anti-stress and anxiolytic activities. It works as an antidepressant by enhancing 5-HT neurotransmission and omega-3s promote transmission of the chemical messengers that facilitate communication between nerve cells and are associated with emotional stability (e.g., serotonin) and positive emotions (e.g., dopamine).[5] Further, it also affects brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which encourages synaptic plasticity, provides neuroprotection, enhances neurotransmission, and has antidepressant effects.[6]

Table 1.

Ingredients of Ashwagandharishta

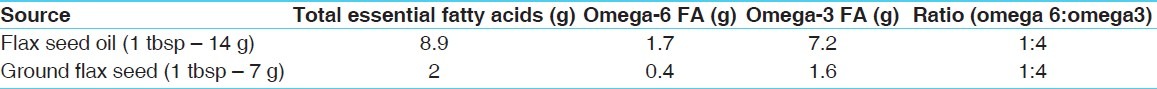

Omega-3 fatty acids (or n-3 PUFAs) are essential for normal brain development and a deficiency in these fatty acids can contribute to the emergence of neurologic dysfunctions. With respect to epilepsy, recent studies in animal models have shown that n-3 PUFAs can raise the threshold of epileptic seizures.[7] The indigenous medicinal plant, called Atasi in Ayurveda, or flax seed, is the best plant source of omega-3 fatty acids. It is the richest source of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) which can be endogenously converted to longer chain omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Flax seed oil delivers greater amount of omega-3s compared to ground flax seed and it is the easiest form to take [Table 2]. Fatty acids may play an important role in the management of seizures[8] and ALA may have anticonvulsant effects.[9]

Table 2.

Comparative essential fatty acids of flax seed oil and ground flax seeds

Lipids are important constituents of the neuronal membrane and fatty acid profile changes may alter membrane functions. Essential fatty acids and phospholipids may: i) offset the deleterious effects of substances that induce seizures, such as iron, that have been shown to increase lipid peroxidation; ii) offer stability in membrane fluidity that may otherwise be associated with seizures; and iii) control the alteration in neuronal membrane phospholipid metabolism that may result from the high prevalence of excitatory amino acid receptors in the epileptic focus. A genetic link may exist between epilepsy and PUFA deficit,[10] and a mixture of DHA and EPA may provide some measure of correction. Furthermore, essential fatty acids may serve as neuroprotectors in the brain, similar to the effects observed in the heart, as shown in recent studies where ALA (but not palmitic acid) was found to protect against ischemic-induced neuronal death, and to prevent kainate-induced seizures and its associated neuronal death.[11]

Thus, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the anticonvulsant activity of Ashwagandharishta and flax seed oil which is the richest plant source of omega-3 fatty acids. Further, protective role of flax seed oil as an adjuvant to Ashwagandharishta has also been evaluated to know its effect on post-ictal depression.

Materials and Methods

Test drugs

Flax seeds were purchased from a commercial dealer (Lallubhai Vrajlal Gandhi Ltd., Gandhi Bridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat) of Ahmedabad in the month of December 2010. The drug was identified and authenticated by pharmacognosist of the institute. Oil was obtained (25%) by traditional grinding and expression pressing method.[12] Ashwagandharishta was procured from the pharmacy attached to SDM college of Ayurveda, Udupi, Karnataka. Milk (which was used as vehicle with flax seed oil) of reputed brand (Amul Taaza) was purchased from local market freshly on the day of experiment.

Animals

Wistar strain albino rats weighing 180 ± 10 g were obtained from animal house (Registration No. 548/2002/CPCSEA) attached to Pharmacology laboratory. Six animals were housed in each cage made up of polypropylene with stainless steel top grill. Dry wheat (post hulled) waste was used as bedding material and was changed every morning. The animals were acclimatized for 7 days before commencement of the experiment in standard laboratory conditions 12 ± 01 h day and night rhythm, maintained at 25 ± 3°C and 50-70% humidity as per Committee for the purpose of control and supervision of experiments on Animals (CPCSEA) guidelines. Animals were provided with balanced food (Amrut brand rat pellet feed supplied by Pranav Agro Mills Pvt. Ltd., Vadodara, Gujarat) and water ad libitum. Protocol used in this study for the use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Approval No. IAEC/09/11/12). Before subjecting them to experimentation, the animals were given a week's time to get acclimatized with laboratory conditions.

Dose selection and schedule

The dose of Ashwagandharishta is 50 ml/day,[13] whereas the human dose of the flax seed oil is 20 ml/day. The dose for experimental animals was calculated by extrapolating the human dose to animals based on the body surface area ratio by referring to the standard table of Paget and Barnes (1964).[14] On this basis, rat dose of Ashwagandharishta was found to be 4.5 ml/kg rat and the dose of flax seed oil was found to be 1.8 ml/kg rat. Flax seed oil was suspended in milk of suitable concentration depending upon the body weight of animals and administered. Phenytoin sodium was selected as the standard antiepileptic drug and administered at a dose of 25 mg/kg.[15] In all groups of animals, the drug was administered orally with the help of gastric catheter sleeved to syringe.

Anticonvulsant activity

The maximal electroshock-induced seizures (MES) test is the most frequently used in an animal model for identification of anticonvulsant activity of drugs like phenytoin for the generalized tonic–clonic seizures.[16] The MES test serves to identify compounds which prevent seizure spread, corresponding to generalized tonic–clonic seizures in humans. This model is based on observation of the stimulation induced by repeated electrical pulses in different neuronal structures.[17]

The rats were pre-tested 24 h prior to administration of test drugs for sensitivity to electric shock and those failing to give hind limb tonic extension were rejected. Thus, the screened animals were divided into six groups of six animals each. Group 1 served as control and received equivalent amount of distilled water. Group 2 served as vehicle control and received equivalent amount of milk. Group 3 received Ashwagandharishta. Group 4 received flax seed oil with milk, whereas Group 5 received flax seed oil along with milk followed by Ashwagandharishta. Sixth group received phenytoin sodium as the standard antiepileptic drug. Experiment was conducted between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m. Seizures were induced in all the groups by using an electro convulsiometer and elicited by a 60-Hz alternating current of 150 mA intensity for 0.2 sec. A drop of electrolyte solution (0.9% NaCl) with lignocaine was applied to the corneal electrodes prior to application to the rats. The animals were observed for the extensor phase as well as its duration and post-ictal depression. The abolition of extensor phase in drug-treated group was taken as the criterion for anticonvulsant activity.[18]

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard error mean (SEM). Difference between the groups was statistically determined by student's t test for unpaired data. Level of significance was set at P <0.05.

Results

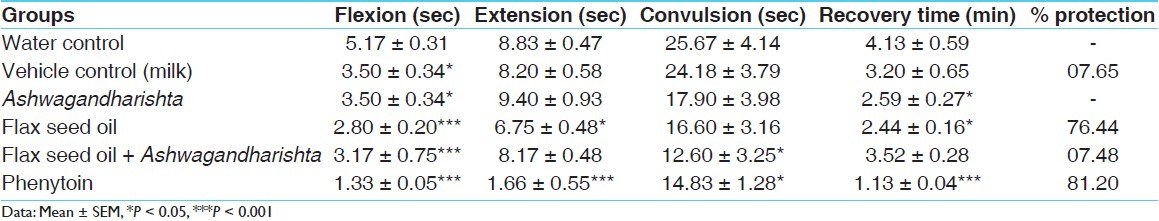

The duration of extensor phase in the control group was 8.83 ± 0.47 sec [Table 3]. Pre-treatment with flax seed oil exhibited significant anticonvulsant activity by decreasing the duration of tonic extensor phase (P < 0.05). However, flax seed oil followed by Ashwagandharishta failed to protect MES-induced convulsion. The standard drug phenytoin significantly abolished the extensor phase in the animals, with 81.20% protection. Pre-treatment with vehicle, flax seed oil, and Ashwagandharishta significantly shortened the flexion phase of MES-induced seizure, while flax seed oil as adjuvant with Ashwagandharishta significantly decreased the duration of convulsion. Further, both flax seed oil and Ashwagandharishta significantly decreased the convulsion phase. The standard drug phenytoin had exhibited significant anticonvulsant effect by abolishing the tonic extension phase. Further, it significantly shortened all other phases induced by MES.

Table 3.

Effect on MES-induced seizures in rats

Discussion

Phenytoin is effective in therapy of generalized tonic–clonic and partial seizures and has been found to show strong anticonvulsant action by increasing the brain content of gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) in MES test.[19,20]

In the present study, a significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the time taken for post-ictal depression was noted in Ashwagandharishta treated group of animals. It also shortened the flexion phase of MES-induced seizures, but failed to decrease the tonic extensor phase [Table 3]. Various ingredients of Ashwagandharishta have proven anticonvulsant activity. Ashwagandha (W. somnifera Dunal) itself possesses antiepileptic properties.[21,22] The major bioactive chemical principles of W. somnifera D. appear to be the glycol-withanolides(WSG).[23,24] WSG have been shown to inhibit ibotenic acid-induced cognitive deficits in rats by reversing rat brain frontal cortical and hippocampal decreases in acetylcholine, choline acetylase, and cholinergic muscarinic receptors produced by the neurotoxin[22] and also exert significant antioxidant effect in various rat brain areas, including striatum n.pl.[23] The other ingredients of Ashwagandharishta like Cyperus rotundus,[25,26] Curcuma longa,[27–30] Terminalia chebula,[31,32] Acorus calamus,[33–36] Pueraria tuberosa,[37,38] and Glycyrrhiza glabra[39,40] are also proven to be effective against experimentally induced seizure models. Thus, the observed effect may be attributed to the combined role of these ingredients.

Flax seed oil exhibited significant anticonvulsant activity by decreasing the duration of tonic extensor phase (P < 0.05), flexion phase (P < 0.001), and recovery time (P < 0.05), with 76.44% protection against MES. This observation confirms the protective effect of omega-3 fatty acid against the seizures as reported earlier.[41] It has been also reported that chronic treatment with omega-3 promotes neuroprotection and positive plastic changes in the brain of rats with epilepsy,[42] with a decrease in neuronal death in CA1 and CA3 subfields of the hippocampus. This could be attributed to n-3 PUFAs’ ion channel modulation[43–45] and anti-inflammatory action. In in vitro studies, DHA has been reported to inhibit epileptiform activity and synaptic transmission mainly through the frequency-dependent blockade of Na+ channels in the rat hippocampus,[43] and to stabilize neuronal membrane by suppressing voltage-gated Ca2+ currents[46] and Na+ channels.[41]

Contrary to the expectations, pre-treatment with flax seed oil as an adjuvant to Ashwagandharishta failed to decrease the tonic extensor phase; however, it significantly decreased the flexion phase (P < 0.001) and duration of the convulsion (P < 0.05). The reason for this observation needs further investigations and also can be tried in other animal models representing epilepsy.

Conclusion

The present study reveals that both Ashwagandharishta and flax seed oil are having antiepileptic activity; besides, they are having excellent anti–post-ictal depression effect. The observed activity may be mediated through inhibition of voltage-dependant Na+ channels or by blocking glutaminergic excitation mediated by the N–methyl–d–aspartate (NMDA) receptor. However, further detailed investigations are needed to explore the exact mechanism involved. Further, both the drugs can play a major role as an adjuvant therapy with modern antiepileptic drugs; however, this needs detailed investigations.

References

- 1.Malvi Reetesh K, Papiya B, Sunny S, Sonam J. Medicinal plants used in the treatment of epilepsy. IRJP. 2011;2:32–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson MJ, Turkington D. Depression and anxiety in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:i45–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.060467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sander JW, Shorvon SD. Epidemiology of the epilepsies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:433–43. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahstri R. Murchchha Rogadhikara. 15-21. Vol. 21. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Surbharati Prakashan; 2007. Bhaishajya Ratnavali; p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health effects on fat: Depression, Omega 3 Fatty acids and Depression: Fats of life news letter. [Last retrieved on 2012 March 11]. Available from: http://www.fatsoflife.com/depression.php .

- 6.Ikemoto A, Nitta A, Furulwa S, Ohishi M, Nakamura A, Fujii Y, et al. Dietary omega 3 fatty acid deficiency decreases nerve growth factor content in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2000;285:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlanger S, Shinitzky M, Yam D. Diet enriched with omega-3 fatty acids alleviates convulsion symptoms in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2002;43:103–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.13601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostofsky DI, Rabinovitz S, Yehuda S. The use of fatty acid supplementation for seizure management. Neurobiol Lipids. 2004;3:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dell CA, Likhodii SS, Musa K, Ryan MA, Burnham WM, Cunnane SC. Lipid and fatty acid profiles in rats consuming different high fat ketogenic diets. Lipids. 2001;36:373–8. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0730-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Søvik O, Mansson JE, Bjorke Monsen AL, Jellum E, Berge RK. Generalized peroxisomal disorder in male twins: Fatty acid composition of serum lipids and response to n-3 fatty acids. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:662–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1005484617709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauritzen I, Bloneau N, Heurteaux C, Widmann C, Romey G, Lazdunski M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are potent neuro protector. EMBO J. 2000;19:1784–93. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhavamishra, Nighantu B, Chunekar K. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Bharati Academy; 2006. p. 653. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health ' Family welfare. New Delhi: Dept. of AYUSH; 2003. Anonymous, the ayurvedic formulary of India, Part I. 2nd ed. Govt. of India; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paget GE, Barnes JM. Evaluation of drug activities. In: Lawrence DR, Bacharach AL, editors. Pharmacometrics. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1964. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senthil Kumar KK, Rajkapoor B. Effect of oxalis corniculata extracts on biogenic amines concentrations in rat brain after induction of seizure. IJP. 2010;1:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loscher W, Schmidt D. Which animal models should be used in the search for new antiepileptic drugs? A proposal based on experimental and clinical considerations. Epilepsy Res. 1988;2:145–81. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(88)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kupferberg HJ. Antiepileptic drug development program: A cooperative effort of government and industry. Epilepsia. 1989;30:S51–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman LS, Grewal MS, Brown WC, Swinyard EA. Comparison of maximal seizures evoked by pentylenetetrazol (Metrol) and electroshock in mice, and their modification by anticonvulsants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1953;108:168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White HS. Clinical significance of animal seizure models and mechanism of action studies of potential antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 1997;38:S9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb04523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald RL, Kelly KM. Antiepileptic drugs: Mechanism of action. Epilespsia. 1991;34:51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulkarni SK, George B. Anticonvulsant action of Withania somnifera root extract against pentylene tetrazole (PTZ)-induced convulsions in mice. Phytother Res. 1996;95:447–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulkarni SK, Sharma A, Verma A, Ticku MK. GABA receptor mediated anticonvulsant action of Withania somnifera root extract. IDMA. 1993:305–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharya SK, Kumar A, Ghosal S. Effects of glycowithanolides from withania somnifera on an animal model of Alzheimer's disease and perturbed central cholinergic markers of cognition in rats. Phytother Res. 1995;9:110–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharya SK, Satyan KS, Ghosal S. Antioxidant activity of glycowithanolides from Withania somnifera. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayur P, Pawan P, Ashwin S, Pravesh S. Evaluation of anti convulsant activity of roots & rhizomes of cyperus rotundus linn. in mice. IRJP. 2011;2:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalili M, Kiasalari Z, Roghani M, Azizi Y. Anticonvulsant and antioxidant effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Cyperus rotundus rhizome on pentylentetrazole-induced kindling model in male mice. JMPR. 2011;5:1140–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srinivas V, Haranath Babu M, Narendra Reddy T, Diwan AV. Modulation of neuotransmitters in mice brains by an anticonvulsant principle from cuttle bone. Indian J Pharmacol. 1997;29:296–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu ZF, Kong LD, Chen Y. Antidepressant activity of aqueous extracts of Curcuma longa in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;83:161–5. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jithendra C, Murthy TE, Upadyay L. Protective role of curcumin in maximal electroshock induced seizures, memory impairment and neurotransmitters in rat brain. JPCCR. 2008;2:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du P, Li X, Lin HJ, Peng W, Liu JY, Ma Y, et al. Curcumin inhibits amygdaloid kindled seizures in rats. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogade Maheshwar G, Deshpande SV, Pramod HJ. Anticonvulsant activity of fruits of terminali chebula retz. against MES and PTZ induced seizures in rats. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology. 2010;4:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debnath J, Sharma UR, Kumar B, Chauhan NS. Anticonvulsant activity of ethanolic extract of fruits of Terminalia Chebula on experimental animals. IJDDR, 2010;2:764–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yende SR, Harle UN, Bore VV, Bajaj AO, Shroff KK, Vetal YD. Reversal of neurotoxicity induced cognitive impairment associated with phenytoin and phenobarbital by acorus calamus in mice. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology. 2009;3:111–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gopalakrishna HN, Pemminati S, Giri S, Shenoy AK, Holla GK, Nair V, et al. Effect of Acorus Calamus on electrical and chemical induced seizures in mice. IJABPT. 2010;1:466–73. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripathi A, Patil MB, Tripathi R. Phytochemical investigation and anticonvulsant activity of acorus calamus. Int J Pharmacol Bio Sci. 2011;5:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jayaraman R, Anitha T, Joshi VD. Analgesic and anticonvulsant effects of acorus calamus roots in mice. International Journal of PharmTech Research. 2010;2:552–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pandey N, Tripathi YB. Antioxidant activity of tuberosin isolated from Pueraria tuberose Linn. J Inflamm. 2010;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basavaraj P, Shivakumar B, Shivakumar H. Evaluation of Anticonvulsant activity of alcoholic extract of tubers of Pueraria Tuberosa (Roxb) Adv Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;12:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kale Shubhangi S, Shete Rajkumar V, Kore Kakasaheb J, Patil Bhaskar M, Bhutada Rupesh N, Pattankude Vinod S. Anti convulsant activity of Glycyrrhizic acid in mice. IJPRD. 2010;2:16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ambawade SD, Kasture VS, Kasture SB. Anticonvulsant activity of roots and rhizomes of Glycyrrhiza glabra. Indian J Pharmacol. 2002;34:251–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cys neiros RM, Ferrari D, Arida RM, Terra VC, de Almeida AC, Cavalheiro EA, et al. Qualitative analysis of hippocampal plastic changes in rats with epilepsy supplemented with oral omega 3 fatty acids. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrari D, Cysneiros RM, Scorza CA. Neuroprotective activity of omega-3 fatty acids against epilepsy-induced hippocampal damage: Quantification with immunohistochemical for calcium-binding proteins. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young C, Gean P, Chiou LC, Shen Y. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits synaptic transmission and epileptiform activity in the rat hippocampus. Synapse. 2000;37:90–4. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200008)37:2<90::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao YF, Kang JX, Morgan JP, Leaf A. Blocking effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids on Na+ channels of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11000–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao Y, Li X. Polyunsatured fatty acids modify mouse hippocampal neuronal excitability during excitotoxic or convulsant stimulation. Brain Res. 1999;846:112–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao YF, Gomez AM, Morgan JP, Lederer WJ, Leaf A. Suppression of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ currents by polyunsaturated fatty acids in adult and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]