Abstract

Aim of the study is to assess the antimicrobial activity Cassia fistula fruit pulp extracts on some bacterial and fungal strains. Hydro alcohol and chloroform extracts of Cassia fistula fruit pulp were evaluated for the potential antimicrobial activity. The antimicrobial activity was determined in both the extracts using the agar disc diffusion method. Extracts were effective on tested microorganisms. The antibacterial and antifungal activities of solvent extracts (5, 25, 50, 100, 250 μg/mL) of C. fistula were tested against two gram positive, two gram negative human pathogenic bacteria and three fungi, respectively. Crude extracts of C. fistula exhibited moderate to strong activity against most of the bacteria tested. The tested bacterial strains were Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coil, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and fungal strains were Aspergillus. niger, Aspergillus. clavatus, Candida albicans. The antibacterial potential of the extracts were found to be dose dependent. The antibacterial activities of the C. fistula were due to the presence of various secondary metabolites. Hence, these plants can be used to discover bioactive natural products that may serve as leads in the development of new pharmaceuticals research activities.

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Antifungal activity, Bacteria, Cassia fistula

Introduction

Antibiotics are one of the most important weapons in fighting bacterial infections and have greatly benefited the health-related quality of human life since their introduction. Drugs derived from natural sources play a significant role in the prevention and treatment of diseases. In many countries, traditional medicine is one of the primary health care system.[1,2] Herbs are widely exploited in the traditional medicine and their curative potentials are well documented.[3] About 61% of new drugs developed between 1981 and 2002 were based on natural products and they have been very successful especially in the areas of infectious disease and cancer.[4] Recent trends, however, shows that the discovery rate of active novel chemical entities is declining.[5] Natural products of higher plants, may give a new source of antimicrobial agents with possibly novel mechanisms of action.[6,7] The effects of plant extracts on bacteria have been studied by a very large number of researchers in different parts of the world.[8] Much work has been done on ethno medicinal plants in India.[9]

In the recent years, researches on medicinal plants have attracted a lot of attention globally. Evidences have been accumulated to demonstrate the promising potential of medicinal plants used in various traditional, complementary, and alternative systems of treatment of human diseases. Plants are rich in a wide variety of secondary metabolites such as tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides etc, which have been found in vitro to have antimicrobial properties.[10,11]

Herbal medicines have been known to man since centuries. Therapeutic efficacy of many indigenous plants for several disorders have been described by practitioners of traditional medicine.[12] Antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants are being increasingly reported from different parts of the world. Traditional medicine continues to be a valuable source of remedies that have been used by millions of people around the world to secure their health.[13] The pharmaceutical industries have produced a number of new antibiotics, resistance to these drugs by microorganisms has increased. In general, bacteria has the genetic ability to transmit and acquire resistance to synthetic drugs that are utilized as therapeutic agents.[14]

Therefore, actions must be taken to reduce this problem, such as to minimize the use of antibiotics and to continue studies to develop new drugs, either synthetic or natural to control pathogenic microorganism. In an effort to expand the spectrum of antibacterial agents from natural resources, Aragvadha (Cassia fistula) belongs to Caesalpiniaceae, which is subfamily of Leguminosae[15–18] has been attempted in this study.

Cassia fistula Linn. a semiwild Indian Labernum also known as the Golden Shower, is distributed in various countries including Asia, Mauritius, South Africa, Mexico, China,West Indies, East Africa, and Brazil as an ornamental tree for its beautiful branches of yellow flowers. Recognize by the British pharmacopoeia.[19] It is widely used for its medicinal properties, its main property being that of a mild laxative suitable for children and pregnant women. It is also a purgative due to the wax aloin and a tonic.[20] It has been reported to treat many other intestinal disorders like healing ulcers.[21,22] The plant has a high therapeutic value and it exerts an antipyretic and analgesic effect.[23]

In the Indian literature, this plant has been described to be useful against skin diseases, liver troubles, tuberculous glands and its use in the treatment of haematemesis, pruritus, leucoderma, and diabetes has been suggested.[24,25] C. fistula extract is used as an antiperiodic agent and in the treatment of rheumatism. It has been concluded that plant parts could be used as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia partially due to their fiber and mucilage content.[26] Beside its pharmacological uses, the plant extract is also recommended as a pest and disease control agents in India.[27–29] This plant is widely used by tribal people to treat various ailments including ringworm and other fungal skin infections.[30] It is used by Malaialis tribe in India to treat nasal infection.[31] The pulp of the ripen fruits has mild, pleasant purgative action and is also used as an antifungal drug.[32] The whole plant is used to treat diarrhea; fruits are used to treat skin diseases, fever, abdominal pain, leprosy by traditional people. C. fistula plant organs are known to be an important source of secondary metabolites, notably phenolic compounds.[33] C. fistula possesses pharmacological activities such as hypoglycemic, anticancer, abortifacient, anticolic, antifertility, estrogenic, laxative, antibacterial, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, smooth muscle stimulant, antiarthritic, antitussive, purgative, analgesic, antifungal, antiviral, hepatoprotective, anti-implantation.[34,35]

C. fistula exhibited significant antimicrobial activity and showed properties that support folklore use in the treatment of some diseases as broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.[36] Thus C. fistula is well anchored in its traditional uses and has now found widespread acceptance across the world.

The current investigation carried out a screening of hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts of C. fistula against pathogenic bacteria and fungi in order to detect new sources of antimicrobial agents. Chloroform extracts were obtained after successive separation from hydro alcoholic extracts which were used for further isolation study. So, the microbial activity of this pure chloroform extracts also needed to check the better results against bacterial and fungal strains. This paper reports the results of the antibacterial and antifungal activity of hydro alcohol and chloroform extracts of fruit pulp.

Materials and Methods

Collection of plant materials

The fresh and healthy pods of plants C. fistula were collected in June–Aug 2009 from various areas of Jamnagar district, Gujarat, India. Fruit pulp of plant has been collected according to the Ayurvedic classical references.[19,34,37,38] The plant specimens were identified in the Pharmacognosy Laboratory of I.P.G.T and R.A., Jamnagar. Plant parts were collected on the basis of the information provided in the ethnobotanical Survey of India. Each specimen/plant material was labeled, numbered, annoted, with the date of collection, locality, and their medicinal uses were recorded.

Extraction

The extraction of the C. fistula fruit pulp was carried out using known standard procedures.[39] The fresh pulp of C. fistula pod (25.0 g) was extracted with 900 ml of diluted methanol, filtered and evaporated to dryness on a hot water bath to yield a hydro alcoholic crude extract (9.7 g). In addition, further with chloroform in a Soxhlet apparatus, where chloroform is a hydrolysate extract and used for further isolation purpose. The extraction was continued until the extraction was exhausted. The extracts were then combined, filtered, and evaporated to dryness.

Further, the crude hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts were cooled and filtered. The concentrated hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts were further subjected for its antimicrobial studies. The residence was dissolved with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with different concentrations and checked it for the antimicrobial activity.

Preliminary phytochemical screening

The extracts were subjected to preliminary phytochemical testing to detect the presence of different chemical groups of compounds. Air-dried and powdered plant materials were screened for the presence of saponins, tannins, alkaloids, flavonoids, triterpenoids, steroids, glycosides, anthraquinones, cumarin, saponins, gum, mucilage, carbohydrates, reducing sugars, starch, protein, and amino acids.[37,40–43]

Test microorganisms and growth media

The following microorganisms: S. aureus (MTCC 96), S. pyogenes (MTCC 442), E. coli (MTCC 443), P. aeruginosa (MTCC 424) and fungal strains A. niger (MTCC 282), A. clavatus (MTCC 1323), C. albicians (MTCC 227) were chosen based on their clinical and pharmacological importance.[44] The bacterial strains obtained from Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh were used for evaluating the antimicrobial activity. The bacterial and fungal stock cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C on Nutrient Agar and Potato Dextrose Agar medium (Microcare lab., Surat, India) following refrigeration storage at 4°C. The bacterial strains were grown in Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates at 37°C(the bacteria were grown in the nutrient broth at 37°C and maintained on nutrient agar slants at 4°C) whereas the yeasts and molds were grown in sabourauddextrose agar (SDA) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) media, respectively, at 28°C. The stock cultures were maintained at 4°C.

Antimicrobial activity

Determination of zone of inhibition method

In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity were examined for hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of plant extracts against four pathogenic bacteria (two gram positive and two gram negative) and three pathogenic fungi were investigated by the agar disk diffusion method.[45–47] Antimicrobial activity testing was carried out by using the Agar cup method. Each purified extracts were dissolved in DMSO, sterilized by filtration using sintered glass filter and stored at 4°C. For the determination of zone of inhibition (ZOI), two gram positive, two gram negative and three fungal strains were taken as a standard antibiotic for comparison of the results. All the extracts were screened for their antibacterial and antifungal activities against the E. coil, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, S. pyogenes, and the fungi C. albicans, A. niger, and A. clavatus. The sets of five dilutions (5, 25, 50, 100, and 250 μg/mL) of C. fistula extract and standard drugs were prepared in double distilled water using nutrient agar tubes. Muller Hinton sterile agar plates were seeded with indicator bacterial strains (108 cfu) and allowed to stay at 37°C for 3 h. The zones of growth inhibition around the disks were measured after 18 to 24 h of in incubation at 37°C for bacteria and 48 to 96 h for fungi at 28°C, respectively. The sensitivity of the microorganism species to the plant extracts were determined by measuring the sizes of inhibitory zones (including the diameter of disk) on the agar surface around the disks, and values <8 mm were considered as not active against microorganisms.

Results

Preliminary phytochemical screening

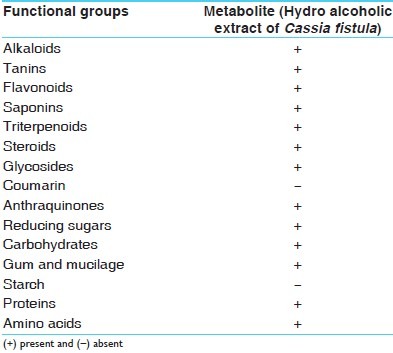

It was found that hydro alcoholic extracts of C. fistula fruit pulp contained tannins, flavonoids, saponins, triterpenoids, steroids, glycosides, anthraquinones, gum and mucilage, reducing sugars, carbohydrates, protein and amino acids, andchloroform extracts contained glycosides, phenolic compounds, tannins, and anthraquinones-type compounds in higher amount [Table 1].

Table 1.

Phytochemical screening of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Microbial activity

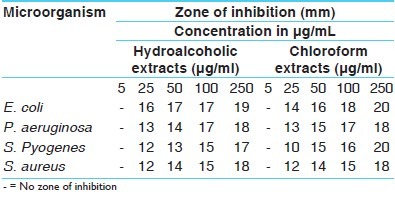

The antimicrobial activity of both the extracts of C. fistula were studied in different concentrations (5 μg/ml, 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, 250 μg/ml) against four pathogenic bacterial strains two Gram positive (S. aureus MTCC 96, S. pyogenes MTCC 442), two Gram negative (E. coli MTCC 443, P. aeruginosa MTCC 424) and three fungal strains(A. niger MTCC 282, A. clavatus MTCC 1323, C. albicians MTCC 227).

Antibacterial and antifungal potential of extracts were assessed in terms of zone of inhibition of bacterial growth. The results of the antibacterial activities are presented in Tables 2–5.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity of hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts of Cassia fistula [zone of inhibition]

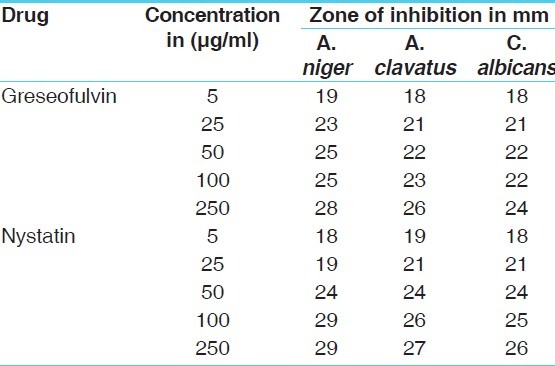

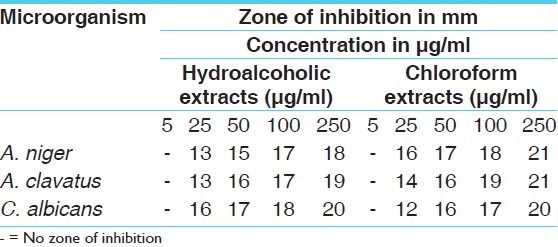

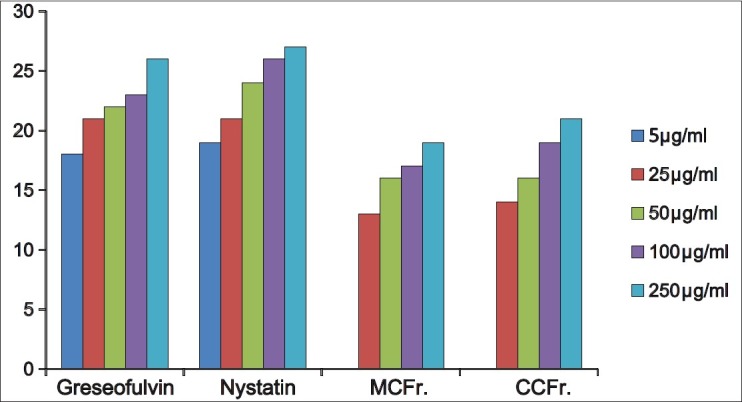

Table 5.

Antifungal activity of standard drugs [zone of inhibition]

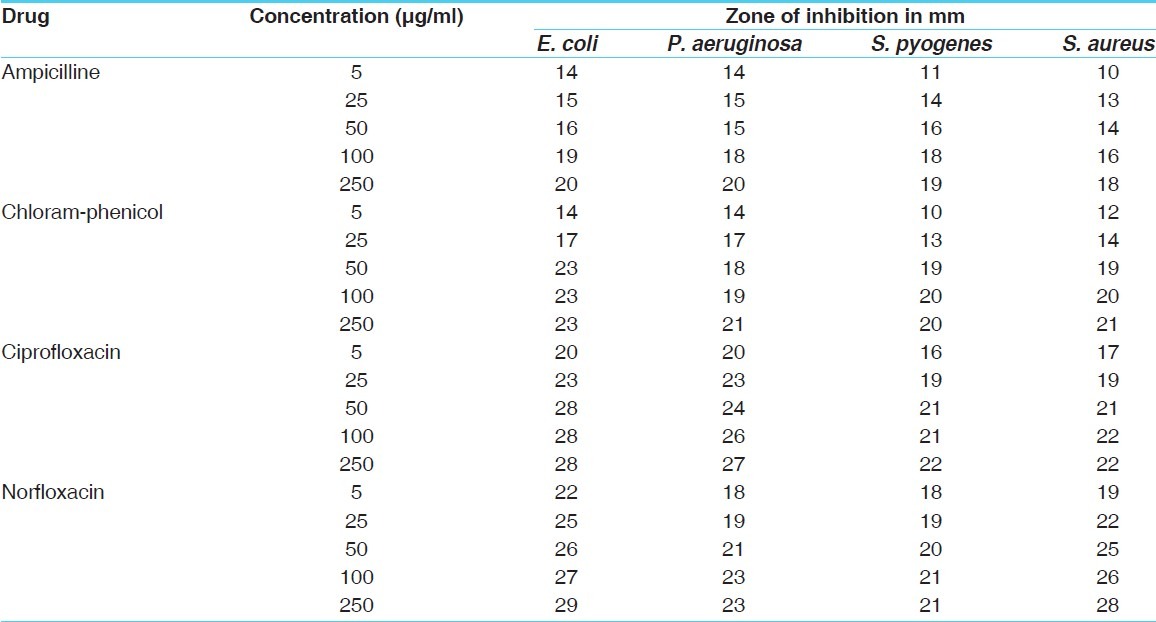

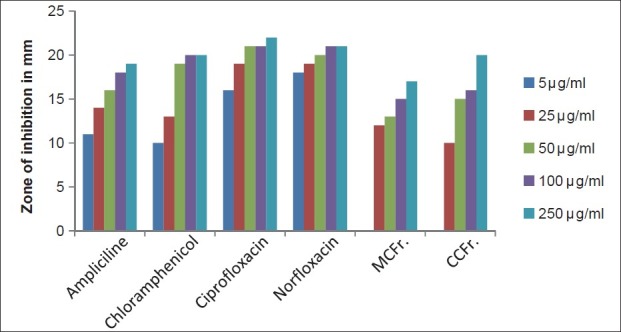

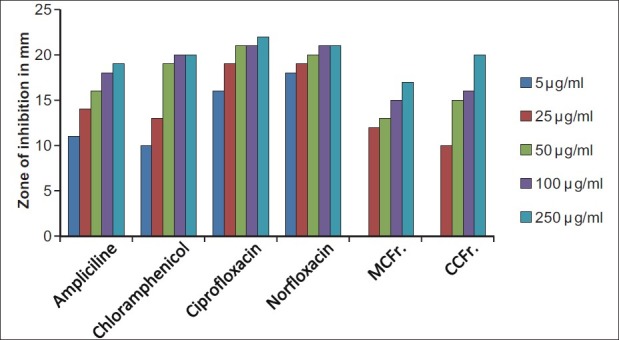

Table 3.

Antibacterial activity of standard drugs [zone of inhibition]

Table 4.

Antifungal activity of hydro alcoholic and chloroform extracts of Cassia fistula [zone of inhibition]

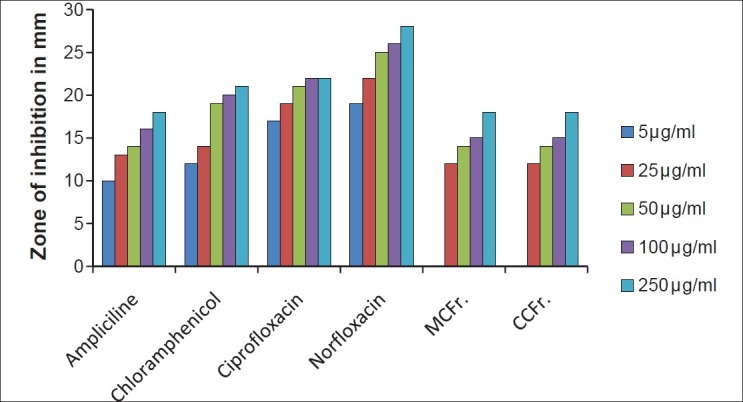

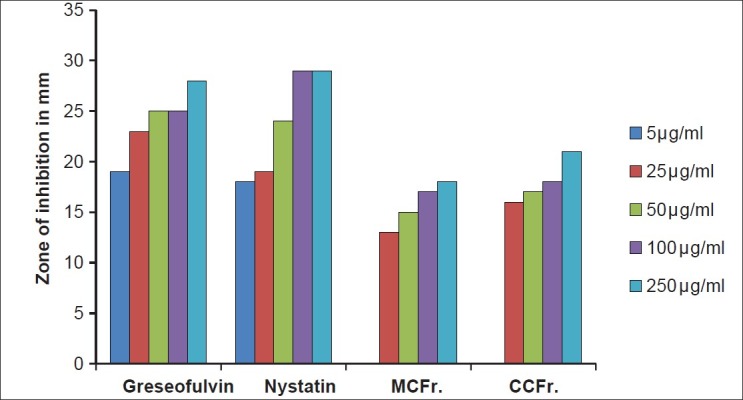

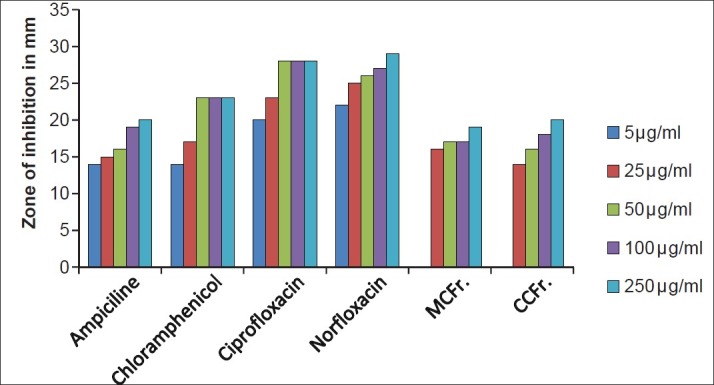

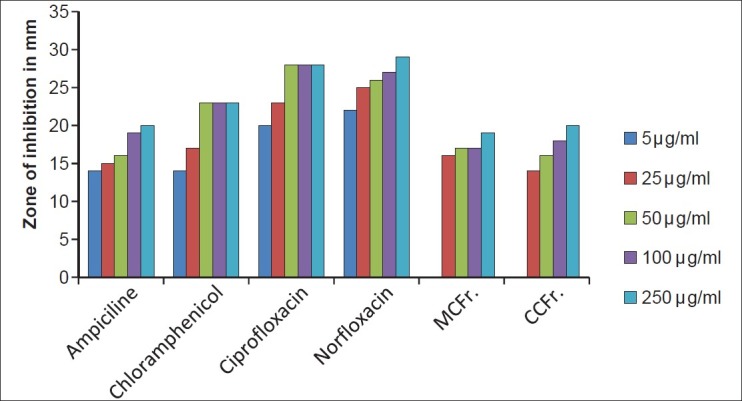

The antibacterial and antifungal activity of the extracts increased linearly with increase in concentration of extracts (μg/ml). As compared to standard drugs, the results revealed that in both the extracts for the bacterial activity, S. pyogenes were more sensitive as compared to S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa, and for fungal activity C. albicans shows good result as compare to A. niger and A. clavatus. The growth inhibition zone measured ranged from 10–20 mm for all the sensitive bacteria, and ranged from 12–21 mm for fungal strains [Figure 1–5].

Figure 1.

Antibacterial activity against S. pyogenes (MTCC 442) MCFr: Methanolic extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 5.

Antifungal activity against A.niger (MTCC 282) MCFr: Methanolic Extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 2.

Antibacterial activity against S. aureus (MTCC 96) MCFr: Methanolic extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activity against E. coli (MTCC 443) MCFr: Methanolic extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 4.

Antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa (MTCC 424) MCFr: Methanolic Extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity against A. clavatus (MTCC 1323) MCFr: Methanolic Extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

Figure 7.

Antifungal activity against C. albicans (MTCC 227) MCFr: Methanolic Extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp, CCFr: Chloroform extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp

The results show that both the extracts of C. fistula were found to be more effective against all the microbes tested.

Discussion

Antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants are being increasingly reported from different parts of the world. The World Health Organization estimates that plant extract or their active constituents are used as folk medicine in traditional therapies of 80% of the words population. In this work, both the extracts obtained from C. fistula fruit pulp shows strong activity against most of the tested bacteria and fungal strains. The results were compared with standard antibiotic drugs. In this screening work, no extracts of C. fistula were found to be inactive against any organism, such as Gram positive, Gram negative and fungal strains were resistant to all the extracts of C. fistula.

This study shows the presence of different phytochemicals with the biological activity that can be of the valuable therapeutic index. The result of phytochemicals in the present investigation showed that the plant contains more or less same components such as saponin, triterpenoids, steroids, glycosides, anthraquinone, flavonoids, gum, mucilage, proteins and aminoacids. From the above results, the activity of hydroalcoholic extracts of C. fistula shows significant antibacterial and antifungal activity. The chloroform extracts, whose purity level is good as compared to hydroalcoholic extract and porosity is lower than hydroalcoholic extract, found to be more active against fungal strains. Results shows that this plant is rich in tannin and phenolic compounds have been shown to possess antimicrobial activities against a number of microorganisms.

Conclusion

Antimicrobial resistance is a global problem. Emergence of multidrug resistance has limited the therapeutic options. Hence, monitoring resistance is of paramount importance. Hence,this study was aimed to focus the antimicrobial properties of C. fistula on gram positive, gram negative, and fungal organisms. In the current investigations, the hydroalcoholic and chloroform extracts of C. fistula were found to be active on some isolated microorganism and fungi as compared to standard drugs. This study has justified the traditional use of fruit pulp in infectious conditions. However, before use in human being isolation of pure compound, toxicological study, and pharmacological activity should be carried out thereafter. However, further studies are needed to better evaluate the potential effectiveness of the crude extracts as the antimicrobial agents.

Acknowledgments

The Authors are thankful to the Director, I.P.G.T. and R.A., Gujarat Ayurved University, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India for invaluable support and for providing of research facilities. We are also thankful to the Mycrocare laboratory, Surat, Gujarat, India for helping and providing necessary facilities for this research work.

References

- 1.Farnsworth NR. Ethno pharmacology and future drug development: The North American experience. J Ethnopharmacol. 1993;38:145–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90009-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houghton PJ. The role of plants in traditional medicine and current therapy. J Altern Complement Med. 1995;1:131–43. doi: 10.1089/acm.1995.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubey NK, Kumar R, Tripathi P. Global promotion of herbal medicines: India's opportunity. Curr Sci. 2004;86:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Biodiversity: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Pure Appl Chem. 2005;77:7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam KS. New aspects of natural products in drug discovery. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Runyoro D, Matee M, Olipa N, Joseph C, Mbwambo H. Screening of Tanzanian medicinal plants for anti-Candida activity. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahidi BH. Evaluation of antimicrobial properties of Iranian medicinal plants against Micrococcus luteus, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumonia and Bordetella bronchoseptica. Asian J Plant Sci. 2004;3:82–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy PS, Jamil K, Madhusudhan P. Antibacterial activity of isolates from Piper longum and Taxus baccata. Pharm Biol. 2001;39:236–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maheshwari JK, Singh KK, Saha S. Ethno botany of tribals of Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh. Economic Botany Information Service, NBRI, Lucknow. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahanukar SA, Kulkarni RA, Rege NN. Pharmacology of Medicinal Plants and Natural Products. Indian J Pharmacol. 2000;32:S81–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowan MM. Plant products as anti-microbialagents. ClinMicrobiol Rev. 1999;12:564–82. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramasamy S, Charles MA. Antibacterial effect of volatile components of selectedmedicinal plants against human pathogens. Asian J Microbiol Biotech Environ, 2004;6:209–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pliangbangchang Samlee., editor. Anonymus. Traditional Herbal Remedies for Primary Health Care. New Delhi: World Health Organization (WHO), Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2010. p. viii. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towers GH, Lopez A, Hudson JB. Antiviral and antimicrobial activities of medicinal plants. J Ethno-pharmacol. 2001;77:189–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.collett Henry., Col. Sir . Flora Simlensis (Flowering plants of Simala), Bengal Army. New Connaught Place, Deharadun: Bishen Singh Mahandrapal Singh; 1971. p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutta AC. Botany. for degree students. 6th ed. Calcutta: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 558. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke T. The Flora of the Presidency of Bombay. Vol. 1. Dehradun: Bishen Singh Mahendrapal Singh; 1976. p. 447. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duthie JF. Flora of the Upper Gangetic Plain. Reprint Edition. Vol. 2. Dehradun: Bishen Singh Mahendrapal Singh; 1994. p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 19.1st ed. Vol. 3. New Delhi: Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1976. Anonymous. The Wealth of India; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satyavati GV, Sharma M. Medicinal Plant in India. New Delhi: ICMR; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas K, Ghosh AB. Advancement of learning. Vol. 2. Calcutta India: Calcutta University; 1973. Bharatia Banawasadhi; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. New Delhi: Jayyed Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel D, Karbhari D, Gulati D, Gokhale D. Antipyretic and analgesicactivities of Aconatum spicatum and Cassia fistula. Pharm Biol, 1965;157:22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam MM, Siddiqui MB, Hussian W. Treatment of diabetes throuherbal drugs in rural India. Fitoterpia. 1990;61:240–2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asolkar LV, Kakkar KK, Chakre OJ. Second supplement to glossary of Indian medicinal plant with active principles. New Delhi: Publication and Information Directorate, CSIR; 1992. p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Saadany SS, El-Massry R.A, Labib SM, Sitohy MZ. The biochemical role and hypocholesterolaemic potential of the legume Cassia fistula in hypercholesterolaemic rats. Die Nahrung. 1991;35:807–15. doi: 10.1002/food.19910350804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaipal S, Sing Z, Chauhan R. Juvenile hormone like activity in extracts of some common Indian plants. Indian J Agric Sci. 1983;53:730–3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma BK, Basandrai AK. Efficacy of some plant extracts for the management of Karnal bunt [Neovossia (Tilletia) indica] of wheat Triticumaestivum. Indian J Agric Sci. 1999;69:837–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raja N, Albert S, Ignacimuthu S. Effect of solvent residues of Vitex negundo Linn. And Cassia fistula Linn. On pulse beetle, Callosobruchus maculates Fab. And its larval parasitoid, Dinarmus vagabundus (Timberlake) Indian J ExpBiol. 2000;38:290–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajan S, Baburaj DS, Sethuraman M, Parimala S. Stem and stembark used medicinally by the TribalsIrulas and Paniyas of NilgiriDistrict, Tamilnadu. Ethnobotany. 2001;6:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perumal Samy R, Ignacimuthu S, Sen A. Screening of 34 medicinal plants for antibacterial properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;62:173–82. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasuko I, Nagayo O. Effects of vegetable drugs on pathogenic fungi I.Effect of anthraquinone-glycoside containing crude drugs upon the growth of pathogenic fungi. Bull Pharm Res InstJpn. 1951;2:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morimoto S, Nonaka G, Chen R. Studies on leaves of Cassia fistula Linn. ChemPharmacol Bull. 1998;36:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandey G., Dr. DravyagunaVijnana. 3rd ed. Reprint Part 3. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy; 2005. p. 167. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavekar GS., Prof . Database on Medicinal Plants used in Ayurveda and Siddha. Vol. 6. Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha, Department of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2009. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar PV, Chauhan NS, Padh H, Rajani M. Search for antibacterial antifungal agents from selected Indian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.1st ed. Part 1. Vol. 3. New Delhi: Govt. of India. Ministry of Health and Family welfare,Dept. of I.S.M. and H; 1990. Anonymous. The Ayurvdic Pharmacopoeia of India. Reprint 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhiman AK. Medicinal Plants of Uttaranchal State. 1st ed. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series office; 2004. p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harborne JB. Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. Chapmanand Hall: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khandelwal KR. Practical Pharmacognosy. 2nd ed. Pune: Nirali Prakashan; 2009. pp. 149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kokate CK. Practical Pharmacognosy. Delhi: New Gyan Offset Printers; 2000. pp. 107–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar A, Ilavarasan R, Jayachandran, Decaraman M, Aravindhan P. Phytochemicals Investigation on a tropical plant in South India. Pak J Nutr. 2009;8:83–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baxi AJ, Shukla VJ, Bhatt UB. Methods of Qualitative Testing of some Ayurvedic Formulation. Jamnagar: Gujarat Ayurved University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCracken WA, Cowsan RA. Clinical and Oral Microbiology. New York: Hemispher Publishing Corporation; 1983. p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alzoreky NS, Nakahara K. Antibacterial activity of extracts from some edible plants commonly consumed in Asia. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;80:223–30. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by standardized single disc method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;36:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rios JL, Recio MC, Villar A. Screening methods for natural products with antimicrobial activity: A review of the literature. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;23:127–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]