Abstract

Amorphophallus paeoniifolius is used for long period in various chronic diseases therapeutically. Aim of the current review is to search literature for the pharmacological properties, safety/toxicity studies, pharmacognostic studies and phytochemical investigation of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber. The compiled data may be helpful for the researchers to focus on the priority areas of research yet to be discovered. Complete information about the plant has been collected from various books, journals and Ayurvedic classical texts like Samhitas, Nighantus etc. Journals of the last 20 years were searched. Particulars of pharmacological activities, phytochemical isolation, toxicity studies etc. were extracted from the published reports focussing on the safety profile of the plant. Safety of the whole plant was concluded in the review.

Keywords: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius, areaceae, phytopharmacological review, safety

Introduction

Importance of herbal medicines

In spite of great advances of modern scientific medicine, traditional medicine is still the primary form of treating diseases of majority of people in developing countries including India; even among those to whom western medicine is available, the number of people using one form or another of complementary of alternative medicine is rapidly increasing worldwide. Increasing knowledge of metabolic process and the effect of plants on human physiology has enlarged the range of application of medicinal plants. According to the report by the World Bank in 1997, (technical paper number 355), it is apparent that the significance of plant based medicines has been increasing all over the world. Nearly 50% of medicines in the market are made of natural basic materials. Interestingly, the market demands for medicinal herbs is likely to remain high because many of the active ingredients in medicinal plants cannot yet be prepared synthetically.[1] The universal role of plants in the treatment of disease is exemplified by their employment in all major systems of medicine irrespective of the underlying philosophical premise. As example, we have western medicine with origins in Mesopotemia and Egypt, the Unani (Islamic) and Ayurvedic (Hindu) systems centred in western Asia and the Indian subcontinent and those of the Orient (China, Japan, Tibet, etc.). How and when such medicinal plants were first used is, in many cases, lost in pre-history, indeed animals, other than man, appear to have their own materia medica. Following the oral transmission of medical information came with the use of writing (example the Egyptian Papyrus Ebers c. 1600 BC), baked clay tablets (some 660 conieform tablets c. 650 BC form Ashurbanipal's library at Nineveh, now in the British Museum, refer to drugs well known today), parchment and manuscript herbals, printed herbals (invention of printing 1440 AD), pharmacopoeias and other works of reference (first London pharmacopoeia, 1618, first British pharmacopoeia 1864), and most recently electronic storage of data. Similar records exists for Chinese medicinal plants (text from the 4th century BC), ayurvedic medicine (Ayurveda 2500-600 BC), and Unani medicine (Kitab-Al-Shifa, the magnum opus of Avicenna, 980- 1037 AD).[2]

The World health Organisation (WHO) estimates that about 80% of the population living in the developing countries rely almost exclusively on traditional medicine for their primary healthcare needs. In al most all the traditional medical systems, the medicinal plants play a major role and constitute their backbone. Indian materia medica includes about 2000 drugs of natural origin almost all of which are derived from different traditional systems and folklore practices. Out of these drugs derived from traditional system, 400 are of mineral and animal origin while the rest are of the vegetable origin. India has a rich heritage of traditional medicine and the traditional health care system has been flourishing in many countries. Most recently, there has been interest in other products from traditional system of medicine Artemisinin is an active antimalarial compound isolated from Artimisia annua, a constituent of the Chinese antimalarial preparation Qinghaosu and forskolin was isolated from Coleus forskohlii, a species used in ayurvedic preparation for cardiac disorders. A new standardized preparation, artemether has recently been introduced for treatment of drug resistant malaria, and new analogues of forskolin are being tested for a variety of uses. Traditional medicine is an important part of healthcare. Population in developing countries depends mainly on the indigenous traditional medicine for their primary healthcare needs. Traditional medicines have not however been incorporated in most national heath systems and the potential of services provided by the traditional practitioners is far from being fully utilized.[3] Herbal medicines are of great impotance to the health of individuals and communities, but their quality assurance need to be developed. During the last decade, the use of herbal medicine has been increased. Consequently, an increase in traditional tread in herbal medicines and other type of traditional medicines has occurred. Proper use of these different types of medicines has therefore become a concern.[3] In recent years, the use of herbal medicines worldwide has provided an excellent opportunity to India to look for therapeutic lead compounds from an ancient system of therapy, i.e. Ayurveda, which can be utilized for development of new drug. Over 50% of all modern drugs are of natural product origin and they play an important role in drug development programs of the pharmaceutical industry.[4] Epidemiological evidence suggests that dietary factors play an important role in human health and in the treatment of certain chronic diseases including cancer.[5,6] Some dietary sources, contain antitumor compounds[7] and such compounds are candidates for chemo preventive agents against cancer development.[8] The anticancer property of nutrients derived from plants as well as nonnutritive plant derived constituents have been proved in different in vitro and in vivo models,[7] which had led to an increased emphasis on cancer prevention strategies in which these dietary factors are utilized.[9] Dietary measures and traditional plant therapies as prescribed by ayurvedic and other indigenous systems of medicine are used commonly in India.[10]

Worldwide revolution for the improvement of patient safety is gaining momentum; hence drug safety for the subject becomes even more prominent in the present day scenario. Cultivation of medicinal plants with laboratory generated species is being attempted on the basis of chemical composition and is likely to be used in increased manner for commercial purposes. These changes may have profound impact on the safety and efficacy of the Ayurveda drugs in the market. Hence, a mechanism is required to be put in place to address them.[11]

Charaka Samhita, an Ayurvedic classic describes all the adverse reactions to medicines when they are prepared or used inappropriately. Charaka also describes elegantly, several host-related factors as to be considered while selecting medicines in order to minimize adverse reactions like the constitution of the patient (Prakriti), age (Vayam), disease (Vikruti), tolerance (previous exposure) (Satmya), psychological state (Satwa), digestive capacity (Ahara-shakti) etc.[12] A possible adverse drug reaction due to Vatsanabha (Aconite) resulting through an overdosing of Ayurvedic drugs was reported.[13] Adverse drug reaction is rarely reported from Ayurvedic drugs and hence this is difficult to find these reports through electronic retrieval system. The basic reason is unawareness of Ayurvedic physicians about collective use to this information resulting in their poor documentation and reporting.[14]

Plant description

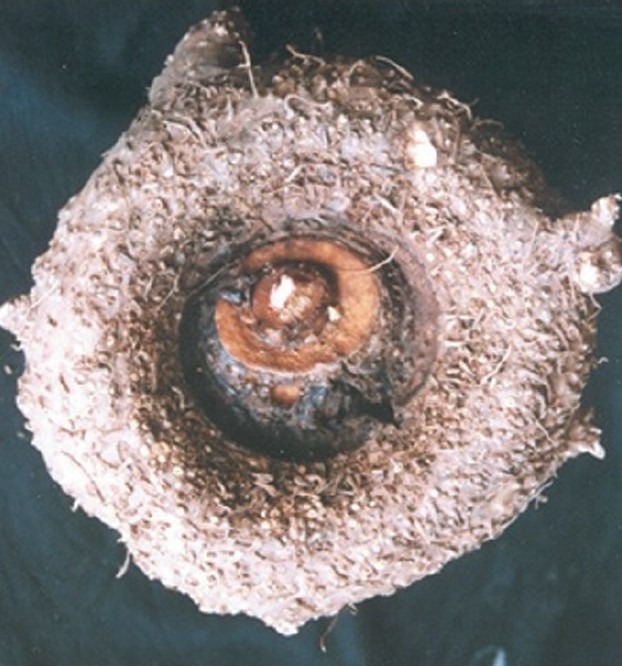

Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson (Syn. Amorphophallus campanulatus Blume ex Decne.) of family Areaceae[15] [Figures 1 and 2] is a tuberous plant commonly used in Ayurvedic medicines as well as tribal medicines in India.

Figure 1.

Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber

Figure 2.

Plant of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius

Scientific classification

Kingdom : Plantae

Phylum : Magnoliophyta

Order : Alismatales

Family : Araceae

Genus : Amorphophallus

Species : A. Paeoniifolius

Binomial name Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson

Synonyms

A. campanulata or Elephant foot yam or Whitespot giant arum or Stink lily,

General description

English Name : Elephant foot yam

Bengali Name : Ol

Sanskrit Name : Suranah

Hindi Name : Suran,Jamikand

Parts Used : Corms

Traditional uses

The corms are acrid, astringent, thermogenic, irritant, anodyne, anti-inflammatory, anti-haemorrhoidal, haemostatic, expectorant, carminative, digestive, appetizer, stomachic, anthelmintic, liver tonic, aphrodisiac, emmenagogue, rejuvenating and tonic. They are useful in vitiated condition of Vata and Kapha, arthralgia, elephantiasis, tumors, inflammations, haemorrhoids, haemorrhages, vomiting, cough, bronchitis, asthma, anorexia, dyspepsia, flatulence, colic, constipation, helminthiasis hepatopathy, splenopathy, amenorrhoea, dysmenorrhoea, seminal weakness, fatigue, anaemia and general debility.[16]

Morphology of the plant

A stout herbaceous plant with underground hemispherical depressed dark brown corm; leaves compound, large, solitary, petiole stout, mottled, 60-90 cm long, leaflets 5-12.5 cm long of variable width, obovate or oblong, acute, strongly and many nerved; male and female inflorescences contiguous, neuters absent, appendage of spadix sub-globose or amorphous, equal or longer than the fertile region, spathe campanulate, pointed,strongly, closely veined, greenish-pink externally, base within purple, margins recurved, undulate and crisped, male inflorescence subturbinate, female 7.5 cm or more long; fruits obovoid 2-3 seeded red berries.[17]

Distribution

The plant is cultivated largely throughout India and also found wild from Punjab to West Bengal, Assam, Konkan, dekkan, Rampa Hills. It is also cultivated in Srilanka.[18,19]

Ayurvedic properties

Rasa- Katu, Kashaya

Guna-Ruksha, Tikshna, Guru, Vishada, Laghu

Vipaka-Katu

Veerya- Ushna

Prabhava- Arshaghana

Doshaghnata- Kapha Vata Shamaka, Kapha-Vata Kara, Pitta-Hara, Kaphagna

Karma- external-Shothahara, Vedanasthapana

Internal-Arshaghna, Vatahara, Kaphahara, Yakrit-Uttejaka

Rogaghnata-externally applied as paste with ghrita and honey in Sandhishotha, Shlipada, Arbuda, internal-Arsha, Pleeha, Gulma, Shwasa, Kasa.

Contraindication-Raktapitta

Dose- Powder 3-6 g.

Formulations and preparations

Siddha properties

Siddha name- Karunai Kilangu

Suvai (Taste)- Kaarppu (Pungent)

Veeriyam (potency)- Seetham (Cold)

Vipakam (Transformation)- Kaarppu (Pungent)

Gunam (Pharmacological actions)- Thuvarppi (Astringent), Ul Azhal Atrri(Demulcent)

Siddha pharmaceutical Preparations- Karunai Kilangu Lehyam

Uses- Used in treatment of anorectal abscess, hemorrhoids.

Phytochemical investigation

Santosa et al. in 2007 isolated 19 polymorphic loci from A. paeoniifolius using a dual-suppression-PCR technique. These loci provide microsatellite markers with high polymorphism ranging from three to 24 alleles per locus. The observed and expected heterozygosities ranged from 0.521 to 0.854 and from 0.766 to 0.930, respectively. This high allelic diversity indicates that the markers are suitable for a population study in A. paeoniifolius.[22]

Methanolic extract (ME) and 70% Hydro-alcoholic extract (AE) of “Amorphophallus paeoniifolius” (Dennst) Nicolson was analysed for flavonoidal content (FC) in terms of Rutin and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) was measured in terms of catechol equivalent. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) study of methanolic extract was conducted. The Flavonoidal content of ME and AE were found to be 46.33 mg/g and 36.88 mg/g respectively. Similarly TPC of study extracts (ME and AE) were found to be 12.67 mg/g and 6.25 mg/g. However the flavonoidal and phenolic contents of ME was found to be higher. Upon TLC of the ME it was observed that there were seven spots at different Rf values.[23]

A flavonoid (Quercetin) from the ethylacetate fraction of corm of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius was isolated by column chromatography using gradient elution method. The isolated flavonoid was characterized by spectral studies.[24]

Pharmacognostic studies

A detailed pharmacognostic morphological, anatomical work and quantitative microscopic standards for the leaves of A. Paeoniifolius was carried out.[25–27]

Macroscopic features

The leaf is compound, solitary, petiole stout, mottled and tripartite showed microscopically dorsiventral in nature with epidermis, parenchyma, sclerenchyma, vascular bundles, air chambers, cell contents and no trichomes. The anatomical details of petiole was also studied. The different leaf constants Stomalal number and Index, Vein islet and termination number, Palisade ratio were determined as a measure of quantitative microscopical standards. Morphological studies were done to determine the characteristics of leaves. The leaves are large, solitary, tripartite; segments spreading, leaflets broad, sessile, obovate or oblong, acute and oblique at the base. The veins parallel, meeting at the ends forming intra marginal veins.

Microscopical features

The anatomy of leaf and petiole was studied by taking the transverse sections followed by staining. The transverse section of leaf shows dorsiventral nature with prominent midrib with lamina attached on the adaxial part spreading laterally. The midrib has a thin epidermal layer of circular to rectangular cells with thin walls, centrally made up of wide air chamber, thick masses of sclerenchyma cells and parenchyma cells. The air chambers are circular or angular vary in size from wide to narrow being located in the central part; the sclerenchymatous cells are found in thick masses located along the periphery of the midrib; the polyhedral, thin walled parenchyma cells covers the remaining portion of the leaf with starch grains and calcium oxalate crystals. The starch grains are solitary and simple measuring 10 to 20 μm diameter. The calcium oxalate crystals of raphides with pointed tips measuring 70 μm long and less than 5 μm thickness in various tissues. There are about ten small collateral vascular strands located in the central part, admixed with air chambers.

The leaf has dorsiventral lamina with a thick adaxial epidermis and a thin abaxial epidermis. The cuticle is less prominent. Numerous paracytic (rubiaceous or parallel celled) stomata are present only in lower epidermis. The mesophyll tissue is made up of narrow band of palisade cells with abaxial spongy cells; the palisade cells are short, single layered conical in shape; the spongy mesophyll has few layers of much lobed and loosely arranged cells enclosing air chambers. The later view has small elliptical collateral vascular bundles with parenchymatous bundle sheet. The petiole is circular in cross sectional view with two short adaxial wings. It has thin distinct continuous layer of epidermis of squarish cells with this walls; inner to the epidermis there are several large masses of collenchyma cells and inner to them are compact fairly wide parenchyma cells. In the central portion there are wide circular air chambers scattered among the parenchymatous ground tissue. The vascular system consists of peripheral strands and central strands; the peripheral strands are placed just aposed to collenchyma and central strands are more or less scattered in between the wide air chambers. The phytochemical screening shows the presence of steroids, in the petroleum ether extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tubers.[25–27]

Pharmacological studies

Toxicity studies

Dey et al. in 2009, found that the petroleum ether extract is safe to be used at a therapeutic dose of 250 mg/kg. The LD50 was found to be 2500 mg/kg in mice.

Analgesic activity

Analgesic activity was evaluated by acetic acid induced writhing response and tail flick method in mice respectively. The methanolic extract of A. Paeoniifolius at the dose levels of 250 and 500 mg/kg body weight administered intraperitoneally exhibited significant analgesic activity in a dose-dependent manner. The standard drug Diclofenac sodium showed significant increase in analgesic activity when compared with the control group of animals.[28,29]

Anti-inflammatory activity

Methanol extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius has prominent anti-inflammatory activity while the chloroform extract has milder activity. 3 hours after the carrageenan injection, the methanol extract at the dose of 200 and 400 mg/kg produced 37.5% and 45.83% inhibition when compared to the control group.[30]

CNS activities

Central nervous system depressant activity was evaluated using Actophotometer and Rota-Rod apparatus. It was found that petroleum ether extract at a doses of 100, 300 and 1000 mg/kg showed significant CNS depressants activity in mice. Intra-peritoneal administration of vehicle (10 ml/kg) did not reduce locomotor activity significantly. After 60 minutes diazepam (0.5 mg/kg) did not reduce locomotor activity to a large extent (38.59% and 42.32%) but diazepam (1.5 mg/kg) decreased locomotor activity significantly (84.89% and 73.66%). Like diazepam, the intra-peritoneal administration of petroleum ether extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tubers (100, 300, 1000 mg/kg) induced a significant decrease in locomotor activity and grip test in a dose-dependent manner. The percentage decrease in locomotor activity are 16.53 (P>0.05), 56.77 (P<0.01), 73.36 (P<0.01) (n=6) and percentage decrease in activity in grip test are 10.38 (P>0.05), 62.67 (P<0.01) and 70.78 (P<0.01) (n=6) 1 hour after the intra-peritoneal administration of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius at the doses of 100, 300, 1000 mg/kg respectively.[31]

Further studies about the probable receptors for central nervous system depressant activity of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius from synergistic drug interaction have been done which found that pet-ether extract has more synergistic activity on the CNS depression with diazepam than phenobarbitone. A spontaneous dose dependent CNS depressant activity was observed with pet-ether extract, diazepam, and phenobarbitone in Swiss albino mice. The pet ether extract of A. Paeoniifolius at the dose level of 100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg bodyweight administered i.p. After 60 minutes, the percentage inhibition of the CNS activity by pet-ether extract was found to be 16.53%, 56.77%, and 73.36% respectively. From the dose response curve, the effective dose (ED50) for the CNS depressant activity was calculated to be 250 mg/kg. Diazepam at the dose level of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg bodyweight administered intraperitoneally. After 60 minutes, the percentage inhibition of the CNS activity was found to be 28.23%, 46.72%, and 91.6%, respectively. Further, from the dose response curve the effective dose (ED50) for the CNS depressant activity was calculated to be 0.5 mg/ kg. Similarly, phenobarbitone at the dose level of 0.5, 5, and 20 mg/kg bodyweight administered intraperitoneally. After 60 minutes, the percentage inhibition of the CNS activity by phenobarbitone was found to be 11.11%, 25.68%, and 70.31%, respectively. From the dose response curve the effective dose (ED50) for the CNS depressant activity was calculated to be approx. 12 mg/kg. The intraperitoneal administration of vehicle (5% Tween 80) at a dose of 10 ml/kg did not reduce locomotor activity significantly. Further, the synergistic activity of pet-ether extract (250 mg/kg) with phenobarbitone (12 mg/kg) was checked and it was observed that after one hour administration of the drugs the percentage inhibition of CNS depressant activity of the combination was calculated to be 59%, which was found slightly higher than the percentage inhibition by pet-ether extract and phenobarbitone individually at their effective doses when compared with control group (vehicle). Similarly, the synergistic activity of pet-ether extract (250 mg/ kg), diazepam (0.5 mg/kg) was checked and it was observed that after one hour administration of drugs the percentage inhibition of CNS depressant activity of the combination was calculated to be 75%, which was much higher than the percentage inhibition by pet-ether extract and diazepam individually at their effective doses when compared with control group (vehicle).[32]

Antimicrobial activity

Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of ethanol extract of tuberous roots of Amorphophallus campanulatus were assessed. Disc diffusion technique was used to determine in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities. Cytotoxicity was determined against brine shrimp nauplii. In addition, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using serial dilution technique to determine antibacterial potency. The extract showed significant antibacterial activities against four gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus β-haemolyticus) and six gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Shigella sonnei, Shigella flexneri, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi). The MIC values against these bacteria ranged from 16 to 128 μg/ml. The antifungal activity was found weak against the tested fungi. In cytotoxicity determination, LC50 of the extract against brine shrimp nauplii was 7.66 μg/ml.[33]

Further antifungal and antimicrobial properties of the various crude extracts of the drug by using cup-plate diffusion method against common pathogens viz., E.coli, S. aureus, E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, C. albicans and A. fumigatus. Among the different extracts, the methonolic extract of A. paeoniifolius was found relatively effective.[34]

A phytoconstituent amblyone, a triterpenoid from A. paeoniifolius and assessed its in vitro antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities. Disc diffusion technique was used for in vitro antibacterial and antifungal screening. Cytotoxicity was determined against brine shrimp nauplii. In addition, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using serial dilution technique to determine the antibacterial potency. Large zones of inhibition were observed in disc diffusion antibacterial screening against four Gram positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis, basillus megaterium, Staphylococcus aureus and Sreptococcus pyrogens) and six Gram negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Shigella sonnei, Shigella flexneri, Pseudomonus aerogenosa and Salmonella typhi). The MIC values against these bacteria ranged from 8 to 64 microgram/ ml. In antifungal screening the compound showed small zones of inhibition against Aspergillus flavus, Aspergilus niger and Rhizopus aryzae. Candida albicans was resistant against the compound. In cytotoxic determination, LC50 of the compound against brine shrimp nauplii was 13.25 microgram/ml.[35]

Anthelmintic activity

The methanolic extracts of the tuber of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius were investigated for their antihelmintic activity against Pheretima posthuma and Tubifex tubifex. The extract with the concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 mg/ml were tested in the bioassay, which involved determination of time of paralysis and time of death of the worms. The extract exhibited significant antihelmintic activity at highest concentration of 100 mg/ml. Piperazine citrate (10 mg/ml) was included as standard reference and distilled water as control. The extracts were found not only to paralyze (Vermifuge) but also to kill the earthworms (Vermicidal).[36]

Hepatoprotetive activity

Shashtry et al. in 2010 isolated a flavonoid (Quercetin) from the ethylacetate fraction of corm of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius and screened for hepatoprotective activity on CCl4 induced model. The flavonoid (Quercetin) was subjected to various biochemical parameters such as SGOT, SGPT, SALP, bilirubin, total protein and histopathology of rat liver were studied. The results were found to be significant by reducing the elevated enzyme levels, increasing the protein level and attenuating the damaged hepatocytes toward the normal texture. The results were further supported by histopathology of isolated rat liver.[24]

Conclusion

The above review reveals that the plant is safer at its therapeutic dose of 250 mg/kg. The plant was found to be potent analgesic, anti-inflammatory, CNS depressant, anthelmintic, antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic agent. It was also seen that the benzodiazepine receptors may be involved for the CNS depressant activity. The phytoconstituents which are present in the plant are mainly steroids and flavonoids which are responsible for the actions. More research is needed to isolate the constituents responsible for the biological actions. It was also observed that no clinical trials have been done so far. So from the current review of literature and ayurvedic text it was concluded that the plant is having high medicinal value.

The traditional and ethnomedicinal literatures showed that the plant is very effective and safe for medicinal uses. By using the reverse pharmacological approaches in natural drug discovery a potent and safe drug can be investigated from the plant for various chronic diseases like liver diseases, cancer, arthritis, and other inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgement

It is indeed our great pleasure to express our sincere gratitude and acknowledgement to the Director General, CCRAS, New Delhi and the Vice Chancellor, Shobhit University, Meerut for their encouragement and support to do this review.

References

- 1.Thomas SC. Medicinal plants culture, utilization and phytopharmacology, Li. United States: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 119–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans WC, Trease GE. Trease and Evans pharmacognosy. 15th ed. China: W.B. Saunders; 2002. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukerjee PK. Quality control of herbal drugs. 1st ed. New Delhi: Business Horizons Publication; 2002. pp. 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker JT, Borris RP, Carte B, Cordell GA, Soejarto DD. Natural product drug discovery and development: New perspective on international collaboration. J Natl Prod. 1995;58:1325–57. doi: 10.1021/np50123a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trichopoulos D, Willett WC. Nutrition and cancer. Cancer Causes Cont. 1996;7:3–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00115633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block G. The data support a role for antioxidants in reducing cancer risk. Nutr Rev. 1992;50:207–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1992.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers AE, Zeisel SH, Groopman J. Diet and carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:2205–17. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorai T, Aggarwal BB. Role of chemopreventive agents in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004;215:129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes S. Effect of Genistein on in vitro and in vivo Models of Cancer. J Nutr. 1995;125:777–83. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.3_Suppl.777S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh B, Bhat TK, Singh B. Potential therapeutic applications of some antinutritional plant secondary metabolites. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:5579–97. doi: 10.1021/jf021150r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gujarat: Gujarat Ayurved University, Jamnagar 361008; 2008. National Pharmacovigilance Protocol For Ayurveda, Siddha And Unani (Asu) Drugs; pp. 8–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thate U. Pharmacoviglance of Ayurvedic medicines in India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2008;40:10–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastogi S. Poor quality and improper use: A review of common reasons of possible adversity in Ayurvedic practice. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2009;21:121–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rastogi S, Ranjana, Singh RH. Adverse effects of Ayurvedic drugs: an overview of causes and possibilities in reference to a case of Vatsanabha (Aconite) overdosing. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2007;19:117–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.New Guinea, Geneva: WHO Western Pacific Regional Publications, World Health Organization; 2009. WHO Monographs on Medicinal Plants in Papua. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair RV. Indian Medicinal Plants 3. Madras: Orient Longman; 1993. pp. 118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal DP. Complementary and alternative medicine: An overview. Curr Sci. 2002;82:518–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heywood, editor. London: Oxford University Press; 1978. Anonymous, Flowering Plants of The World; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. Vol. 4. Allahabad, India: Published by Lalit Mohan Basu; 1989. pp. 2609–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.1st ed. Part-I. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. Of India; 1978. Anonymous, The Ayurvedic Formulary of India. [Google Scholar]

- 21.1st English ed. Part-II. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Dept. Of ISM and H, Govt. of India; 2000. Anonymous, The Ayurvedic Formulary of india. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santosa E, Lian CL, Pisooksantivatana Y, Sugiyama Y. United States: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. [Last accessed on 2011 Apr 04]. Isolation and characterization of polymorphic microsatellite markers in Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson, Araceae. Available from: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118523830/abstract . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nataraj HN, Murthy RL, Setty SR. Invitro Quantification of Flavonoids and Phenolic content of – Suran. Int J ChemTech Res. 2009;1:1063–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharstry RA, Biradar SM, Mahadevan KM, Habbu PV. Isolation and characterization of Secondary Metabolite from Amorphophallus paeoniifolius for Hepatoprotective activity. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2010;1:429–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nataraj HN, Murthy RLN, Setty SR. Pharmacognostical parameters for evaluation of leaves of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius. J Pharm Res. 2009;2:1370–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De S, Dey YN, Ghosh AK. Phytochemical investigation and chromatographic evaluation of the different extracts of tuber of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius. Int J Pharm Biol Res. 2010;1:150–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey YN, Ghosh AK. Pharmacognostic evaluation and phytochemical analysis of tuber of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius. Int J Pharm Res Dev. 2010;2:44–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dey YN, De S, Ghosh AK. Evaluation of Analgesic activity of methanolic extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber by tail flick and acetic acid-induced writhing response method. Int J Pharm Biosci. 2010;1:662–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shilpi JA, Ray PK, Sarder MM, Uddin SJ. Analgesic activity of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber. Fitoterpia. 2005;76:367–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De S, Dey YN, Ghosh AK. Anti-inflammatory activity of methanolic extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius and its possible mechanism. Int J Pharma Biosci. 2010;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das SS, Sen M, Dey YN, De S, Ghosh AK. Effects of petroleum ether extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber on central nervous nystem in mice. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2009;71:651–5. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.59547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dey YN, De S, Ghosh AK, Gaidhani S, Kumari S, Jamal M. Synergistic depressant activity of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius in swiss albino mice. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:121–3. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.81910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan A, Rahman M, Islam S. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of tuberous roots of amorphophallus campanulatus. Turk J Biol. 2007;31:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natraj HN, Murthy RL, Setty SR. In vitro screening of antimicrobial activity and Preliminary phytochemical screening of – suran. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;1:189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan A, Rahman M, Islam MS. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of amblyone isolated from Amorphophallus campanulatus. Indian J Pharmcol. 2008;40:41–4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.40489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dey YN, Ghosh AK. Evaluation of anthelmintic activity of the methanolic extract of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2009;1:117–21. [Google Scholar]