Abstract

Purpose

Two point-of-care (POC) tests are available to detect bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common vaginal condition. This study aimed to 1) compare the accuracy of two self-performed BV tests to clinician-performed BV tests and to clinical BV; and 2) compare trust of results for self-BV testing compared to clinician-BV testing.

Methods

Participants (14–22 years old) in a study assessing self-testing for Trichomonas vaginalis were also asked to perform a self-test for BV (using a pH or sialidase test). Results were compared to clinician-tests and to clinical BV (defined by modified Amsel’s criteria). A two-item subscale from a larger acceptability scale was used to assess trust at baseline, after testing, and after discussion of results.

Results

All 131 women performed self-BV testing correctly. Agreement between self- and clinician-tests was good (Kappa 0.5–0.7). Compared to clinical BV, self-pH was 73% sensitive and 67% specific, and self-sialidase was 40% sensitive and 90% specific. Trust in self-BV testing was lower than trust in clinician-BV testing at baseline, but increased after testing and discussion of results.

Conclusions

Young women can perform self-tests for BV with reasonable accuracy, which could increase testing when pelvic exams are not feasible. Trust in self-testing increased after experience and after discussion of test results. Although the pH test is over-the-counter, young women may continue to rely on clinicians for testing.

Keywords: Adolescent, Vaginosis, Bacterial, Point-of-Care Systems, Patient Acceptance of Health Care, Genital Diseases, Female

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common lower genital tract condition among women. Data from the 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) prevalence survey determined that BV affects nearly one-third of American women aged 14–49 years [1]. BV was reported in about 23% of 14–19 year old women, and was found in 10–18% of women who reported never having vaginal sex [1–4]. Bacterial vaginosis is caused by disruptions of the normal flora in the vagina and has been associated with several other conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease, preterm labor, and post-surgical infections [5–9]. Most concerning is a link between the presence of BV and acquisition of HIV [10,11]. Because BV is both common and often linked to poor reproductive health outcomes, improved detection of BV may be warranted.

Diagnosis of BV can be difficult. The research gold standard to diagnose BV is to use a Nugent’s score of ≥ 7 on a Gram stain of a vaginal sample [12]. However, Gram stain is rarely available or utilized in clinical settings and is reported to be about 85% sensitive and 85% specific compared to the Amsel’s clinical criteria [13,14]. The most common method used to diagnose BV is the Amsel’s criteria, in which three of the following four findings are present: a) homogeneous white discharge; b) >20% clue cells on wet mount; c) positive “whiff” (i.e., the presence of an amine odor after application of potassium hydroxide to the vaginal sample); and d) vaginal pH >4.5 [15]. However, a significant amount of clinical experience and microscopy skill is required to identify these fairly subjective criteria. Therefore, in many settings clinicians use modifications or components of the Amsel’s criteria to ascertain BV. We present the relative sensitivities and specificities of various BV diagnostic tools in Table 1 [16].

Table 1.

Comparison of diagnostic methods for BV

| BV Test | Sensitivity Vs. Nugent's |

Specificity Vs. Nugent's |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amsel’s (Any 3 of 4) | 69–78 | 58–94 | [13,16,23] |

| Modified Amsel’s: | |||

| pH>4.5 + >20% clue + positive whiff | 55 | 98 | [13] |

| pH>4.5 | 77–89 | 70–74 | [1,13 23] |

| >20% clue | 60–74 | 86–94 | [13,23] |

| Positive whiff | 67 | 93 | [23] |

| pH + amine | 64 | 95 | [23] |

| Sialidase (BVBlue) | 88–92 | 95–98 | [24,25] |

| pH or Amines (FemExam®1) | 89 | 61 | [23] |

In addition to limited test modalities, another barrier to BV diagnosis is that both the Gram stain and Amsel’s criteria require samples obtained during a pelvic exam. For adolescent women, a pelvic exam is a barrier to care [17]. However, vaginal samples can be collected by the clinician or the patient, which would remove the need for a speculum exam [18,19]. A final barrier to BV diagnosis and treatment is that women with BV may erroneously diagnose themselves with another condition such as a yeast infection if they do not seek care from a clinician [20]. Self-treatment for a yeast infection may delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, if a BV self-testing option were available, it may increase the proportion of women who are accurately diagnosed and treated for BV.

Two simple point-of-care (POC) tests are now available to improve the detection of BV. An over-the-counter vaginal pH test has been available since 2001. With this test, women who detect an abnormal pH (>4.5) are directed to seek medical care for further diagnosis [21]. Some authors have shown that the pH test will increase appropriate diagnosis and treatment [22]. Abnormal pH alone is reported to have 77–90% sensitivity and approximately 70% specificity for BV [1,13,23]. Another POC test for BV detects sialidase, an enzyme produced by BV-associated bacteria. This test is CLIA-waived and has been marketed for use by health professionals since 2006. The sialidase test has a reported 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity for BV [24,25]. Both of these tests are somewhat subjective in that they require the tester to recognize a color change from yellow to green (pH) and from yellow to blue (sialidase). Neither of these tests has been evaluated for use in adolescent women, and the sialidase test has not been evaluated as either a self-collected sample or as a self-performed test.

In our prior work we showed that young women could accurately use a POC product developed for use by health professionals to self-test for Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), and that acceptability for self-testing improved after experience with self-testing [26,27]. However, it is unknown whether young women can accurately perform self-tests for BV and whether BV self-testing would be acceptable to them.

The goal of this study was to evaluate strategies to improve the diagnosis of BV in adolescent women. The specific aims were: 1) to compare the accuracy of self-performed pH and sialidase tests to the corresponding clinician-test and to the clinical diagnosis of BV (using modified Amsel’s criteria); and 2) to compare trust in the results of self-BV testing to clinician-BV testing.

METHODS

Participants and Study Flow

Sexually active women ages 14–22 years were recruited from an urban children’s hospital for a larger study assessing the accuracy and acceptability of self-testing for TV [26,27]. The methods and results of the larger study have been described, and the study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board with a waiver for the requirement of parental permission for those women less than 18 years old. In addition to self-testing for TV, each woman in the parent TV study was offered the option of self-testing for BV (using either the pH or sialidase test) on a self-obtained vaginal swab. Participation was voluntary, as the investigators and IRB considered that the addition of the second self-test might be an additional burden that could have dissuaded subjects from participating in the parent TV study.

The study flow was as follows: At baseline, after obtaining informed consent, we collected information on demographic characteristics, sexual history, and behavioral data, and a brief (pre-testing) acceptability survey. BV testing was then performed: the clinician collected swabs during a pelvic examination and the participant self-collected swabs and performed the BV test. During the pelvic exam, the clinician collected additional endocervical swabs for Chlamydia and gonorrhoea nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), and a vaginal swab for trichomoniasis testing. The order of testing (clinician-collected first versus self-collected first) depended upon clinic flow. After the testing, the participant completed the second (post-testing) acceptability survey. Then, the study team reviewed the results of the self- and clinician-tests with the participant. After this discussion, the participant completed a third (post-discussion) acceptability survey.

Laboratory Testing

Clinician-collected vaginal swabs were tested for BV (wet mount, pH, amines, and sialidase) and for TV (using a POC rapid antigen test). Endocervical swabs were tested for Chlamydia and gonorrhoea by NAAT (Aptima Combo2, Gen-Probe, Inc.). Following written and verbal instructions, each participant tested her vaginal swab with one BV test, either pH (pHem-alert®, Gynex Corporation, Redmond, WA) or sialidase (OSOM® BVBlue®, Sekisui Diagnostics, LLC, Framingham, MA). After the participant reported her result, the research assistant observed the device, confirmed that the participant’s reading was correct, and recorded the results on the data form. The choice of BV test was determined by device availability as follows: the first 11 women were offered the sialidase test because the pH device was not on hand; the next 91 women were offered either test based on a coin-flip (performed by the research assistant), and the last 29 to be recruited were offered the pH test because we only had the pH test available at that time. Experienced clinicians performed the wet mount. A trained research assistant performed the amine and pH test for all participants, and performed the sialidase test if the participant also performed the sialidase test. For self- and clinician-tests, the pH was read by comparing the color to an accompanying chart. Although pH results were recorded in 0.5 unit increments, for the purposes of analyses a pH >4.5 was defined as abnormal. A positive sialidase result was indicated by a blue or green color and a negative result was yellow. The amine test was deemed positive if a strong fishy odor was detected after a 10% solution of potassium hydroxide was applied to the vaginal swab sample [5]. Clinical BV was defined by modified Amsel’s criteria: >20% of epithelial cells on a wet mount were clue cells, pH >4.5 on clinician-testing, and positive amines [13].

Acceptability/Trust Assessment

Acceptability of self- and clinician-testing was assessed at each time point using items from a previously validated survey [27,28]. For the current study, we limited the assessment of acceptability to two items comprising a subscale assessing trust in test results: 1) Do you believe that the other vaginitis test result will be correct for the sample that you (or the clinician) collect? 2) How much will you trust the result of the other vaginitis test that you (or the clinician) collect? Each item was rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale (range 1–3, with 1 indicating low acceptability and 3 indicating high acceptability) for the two outcomes: clinician-BV test and self-BV test. For each outcome, the mean of the two items assessing trust was used, and analyzed as a continuous variable. In our prior work, we showed that the internal consistency reliability was good for the two-item trust scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89) [27].

Analyses

Differences between those who agreed to versus those who declined BV self-testing were assessed using chi-square tests. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for sensitivity and specificity were generated. Agreement between self- and clinician-tests results and to clinical BV was compared using chi-square and Kappa statistics. Experts characterize Kappas over 0.75 as excellent, 0.40 to 0.75 as fair to good, and below 0.40 as poor [29]. As in our prior work, we used the mean scores for two items in the trust subscale rather than generating a summary score [27]. The changes in trust scores over time were assessed separately for self- and clinician-testing using paired t tests. The difference between self- and clinician-testing at each time point was compared using paired t tests. Because there were multiple outcomes at each time point, we used repeated measures ANOVA to assess changes in mean trust scores over time and to compare self- to clinician-testing.

RESULTS

Of 246 women in the original study, 131 (53%) agreed to self-BV testing (Table 2). Those who agreed were more likely to be non-Black (18% vs. 9%, p=.03) and to have clinical BV (25% vs. 14%, p= .03) compared to those who declined. Those who agreed were less likely to have Chlamydia (16% vs. 31%, p<.01) or gonorrhea (3% vs. 17%, p<.01) than those who did not agree, but did not differ in terms of vaginal symptoms, prior sexually transmitted infection (STI), multiple partners, condom use, prior use of a home pregnancy test, or trust in TV self-testing at any time point. The 79 women who performed the pH test did not differ in any of the above characteristics from the 52 women who performed the sialidase test.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 246 women by whether they agreed or declined BV self-testinga

| Participant Characteristics | Declined BV self- test n (%) |

Agreed to BV self- test n (%) |

Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | n= 115 | n= 131 | n= 246 | 0.66 |

| 14–17 | 55 (48) | 59 (45) | ||

| 18–21 | 60 (52) | 72 (55) | ||

| Race | n= 115 | n= 131 | n= 246 | 0.03 |

| Non-Black | 10 (9) | 24 (18) | ||

| Black | 105 (91) | 107 (82) | ||

| Previous Use Of Home Pregnancy Test | n= 115 | n= 129 | n= 244 | 0.94 |

| Yes | 69 (60) | 78 (60) | ||

| Vaginal Discharge or itching | n= 115 | n= 131 | n= 246 | 0.10 |

| Yes | 79 (69) | 102 (78) | ||

| Hormonal Contraception Used | n= 111 | n= 126 | n= 237 | 0.08 |

| Yes | 33 (30) | 51 (40) | ||

| Was Condom Used at Last Vaginal Sex | n= 113 | n= 128 | n= 241 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 36 (32) | 52 (41) | ||

| Clinician Sialidase positive | n= 10 | n= 106 | n= 116 | 0.90 |

| Yes | 2 (20) | 23 (22) | ||

| Clinical BV (pH>4.5 + clue cell+ amine) | n= 109 | n= 127 | n= 236 | 0.03 |

| Yes | 15 (14) | 32 (25) | ||

| Clinician pH | n= 108 | n= 131 | n= 239 | 0.19 |

| abnormal pH>4.5 | 66 (61) | 69 (53) | ||

| Amine Test Result | n= 109 | n= 130 | n= 239 | 0.61 |

| Positive | 50 (46) | 64 (49) | ||

| >20% Clue Cells on Wet Mount | n= 114 | n= 128 | n= 242 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 27 (24) | 54 (42) | ||

| POC Trichomonas Test Result | n= 115 | n= 131 | n= 246 | 0.08 |

| Positive | 31 (27) | 23 (18) | ||

| Chlamydia Test Result | n= 101 | n= 115 | n= 216 | 0.008 |

| Positive | 31 (31) | 18 (16) | ||

| Gonorrhea Test Result | n= 101 | n= 115 | n= 216 | 0.001 |

| Positive | 17 (17) | 4 (3) | ||

Totals differ due to missing data

Accuracy

All 131 women performed the self-test correctly. Agreement between the self- and clinician-tests for pH was 76% (Kappa 0.53). Agreement between self- and clinician-tests for sialidase was 92% (Kappa 0.7) (Table 3). Compared to the clinical diagnosis of BV, self-testing for pH was 73% sensitive and 67% specific, and self-testing for sialidase was 40% sensitive and 90% specific (Table 4). Self-performed BV tests were not significantly different from clinician-performed BV tests in terms of clinical BV detection. Clinician-testing for pH was 100% sensitive and 64% specific and clinician-testing for sialidase was 52% sensitive and 88% specific to detect clinical BV. The higher sensitivity of clinician pH is explained because an abnormal clinician pH was included in the definition of clinical BV. However, the confidence intervals for sensitivity of self and clinician pH testing overlapped, suggesting that the two tests were not significantly different.

Table 3.

Correlation between self- and clinician-POC tests. Sensitivity and specificity calculated using the corresponding clinician test as the reference.

| Clinician Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative | positive | Kappa | Percent agreement |

Sensitivity % (95% CI) |

Specificity% (95% CI) |

||

| Self pH | negative | 29 | 14 | ||||

| N=77 | positive | 4 | 30 | 0.53 | 76% | 68 (52–81) | 88 (72–96) |

| Self sialidase | negative | 41 | 3 | ||||

| N=51 | positive | 1 | 6 | 0.7 | 92% | 67 (30–92) | 98 (87–100) |

Table 4.

Performance of self- and clinician-tests to the clinical diagnosis of BV (modified Amsel’s criteria)a

| Total tested |

True Positive (TP) |

False Positive (FP) |

True Negative (TN) |

False Negative (FN) |

Sensitivity (TP/TP+FN) |

Specificity (TN/TN+FP) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||||||

| Self pH | 77 | 16 | 18 | 37 | 6 | 73 | 50–89.3 | 67 | 53–79 |

| Clinician pH | 127 | 32 | 34 | 61 | 0 | 100 | 89.1–100 | 64 | 54–74 |

| Self Sialidase | 52 | 4 | 4 | 38 | 6 | 40 | 12–74 | 90 | 77–97 |

| Clinician Sialidase | 105 | 14 | 9 | 69 | 13 | 52 | 32–71 | 88 | 80–94 |

Total n tested varies due to missing data; more participants had clinician-testing than self-testing.

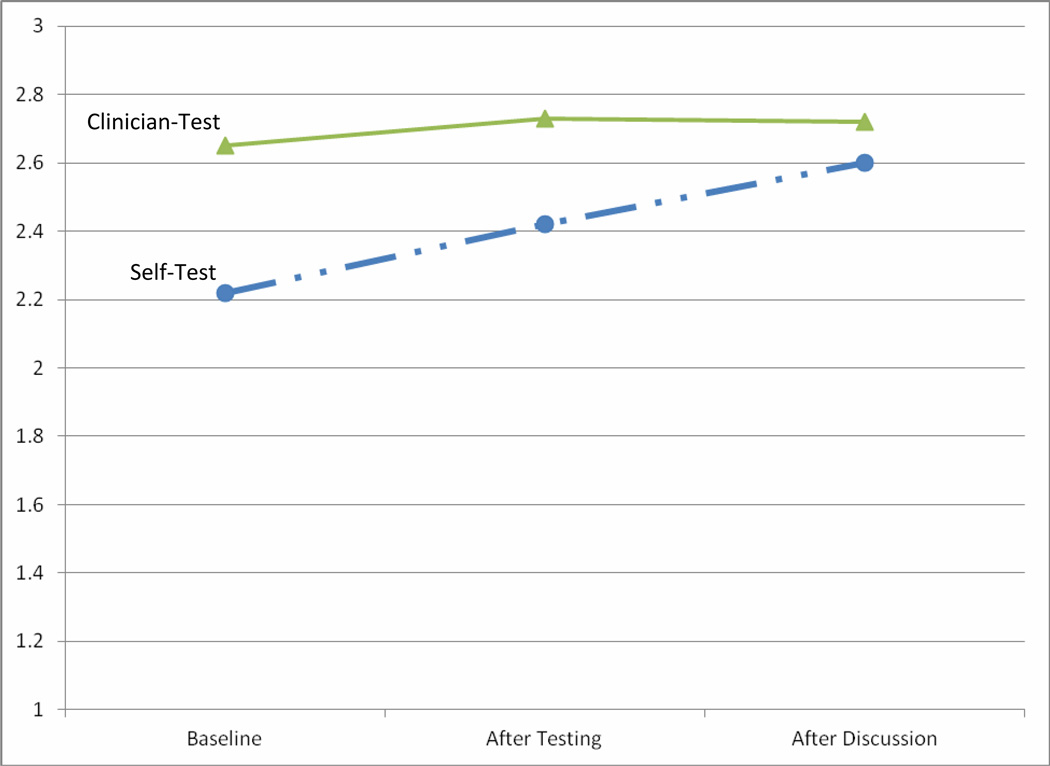

Acceptability

The mean score for the subscale measuring trust in BV test results at baseline was 2.22 (range 1–3, standard deviation 0.45). The internal consistency reliability was good for the two-item trust scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.70). At baseline, trust in self-BV testing was lower than trust in clinician-BV testing (2.22 vs. 2.65, p<.01). Trust in clinician-BV testing did not change significantly over the three time points (2.65 to 2.73 to 2.72, p=.24). Trust in self-BV testing increased after experience (2.22 to 2.42, p<.01), and again after discussion of test results (2.42 to 2.6, p<.01). After discussion of test results, trust of self- and clinician-BV testing were not significantly different (2.6 vs. 2.72, p=.08) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in Trust of BV self-test compared to BV clinician-test over three time points The Y-axis represents the mean score of the two-item trust subscale (range 1–3). Time points are baseline (before testing), after self- and clinician-testing, and after a discussion of self- and clinician-test results. The trust of BV self-test results (dashed line) increased at both time points, whereas the trust of clinician BV test results (solid line) was high and did not change over time.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that young women can perform self-collected tests for BV correctly and with reasonable accuracy compared to clinician-testing. In this study sample, the results of self-testing and clinician-testing for BV did not differ significantly. Self-collecting and performing tests is an approach that could increase rates of testing in settings where it is not feasible or desirable to perform a speculum examination. The point estimates that we found for self-vaginal pH are similar to the published range for clinician-testing (77–89% sensitive and 70–74% specific compared to Amsel or Nugent’s criteria for BV) [1,13,23]. In contrast, the sensitivity of the sialidase test that we found (40–52%) was far below published reports of 88–92%, while specificity was similar (90%) to the 95–98% in published studies [24,25]. However, neither pH nor the sialidase test alone, whether performed by the clinical staff or the participant, demonstrated optimal sensitivity and specificity compared to Amsel’s criteria.

In this sample of adolescent and young adult women, we found a lower agreement between self-testing for pH and clinician-testing for pH (76% agreement, Kappa 0.53) than the 0.9 Kappa reported for adult women using the same pH device [22]. The sialidase test had moderate agreement (92% agreement, Kappa 0.7) between self- and clinician-tests. In our prior work, we showed that the self and clinician POC TV tests were highly correlated (96% agreement, Kappa 0.87) [26]. These differences might be explained in part by differences in the complexity of test procedures and interpretation. The pH test requires observers to note the difference in a range of colors (one normal and six abnormal choices) and the sialidase test requires observation of a change from yellow to blue or blue-green, while the TV POC test displays a colored line designating a positive result, similar to a home pregnancy test. In our sample, nearly two-thirds of young women had performed a home pregnancy test in the past and thus may have been more familiar with interpreting the results of the POC TV test.

Trust in the results of self-testing for BV increased when young women had the opportunity to try the test and discuss results with the clinician, which mirrors our results with respect to trust in self-testing for TV [27]. Trust in self-testing for BV was similar to the trust in self-testing for TV that we reported previously. This suggests that trust is not impacted by perceived severity or stigma associated with either diagnosis, or with any difficulty in reading or interpreting the test results. The pH test is already marketed for over-the-counter use, but it is not known whether adolescents are using it. In the future, young women may have access to other self-testing strategies for vaginitis, but may continue to rely on clinicians if they trust clinician-collected tests more than self-collected tests.

One limitation to this study is that we did not use Nugent’s Gram stain criteria to diagnose BV. However, the Gram stain is rarely used in clinical practice. In addition, the Nugent score of 7–10 is reported to be about 85% sensitive and specific when compared to Amsel’s clinical criteria [13,14]. Thus, the clinical utility of POC BV tests should be compared to what is clinically available. In the case of BV, we are faced with the dilemma of determining how best to detect a condition for which no perfect gold standard exists [30]. In the future, a more useful approach may be to determine which aspects of the heterogeneous condition known as BV (e.g., pH, amines, sialidase) are important for clinical outcomes.

Another limitation is that the study population is a sample of women recruited from an ambulatory clinical setting who volunteered to perform BV self-testing after volunteering for a study about TV self-testing. We showed that those who agreed to test for BV were more likely to be white, to have clinical BV, and less likely to have an STI. However, they did not differ from those who declined in their baseline trust of TV self-testing at any time point. Still, all of the women who participated in the parent study or the BV sub-study may differ from those who declined to participate, and may have a higher overall trust in self-testing results. Participants also might be more comfortable with self-testing in general, which might mean their results could be more accurate than the results of those who did not volunteer. Finally, results from women who are seen in a clinical setting may not be generalizable to other groups.

In conclusion, asking young women to self-collect vaginal swabs and to perform self-testing for BV using easy POC tests is feasible and acceptable. Young women express more trust in test results if they are able to try the test and review their results with a clinician. In the future, we should assess how developing better POC tests and using self-testing strategies may engage young women to become active participants in their own reproductive health.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

We evaluated the accuracy and trust of self-testing for bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common condition that is distressing to many women. Our findings show that BV self-testing is feasible and acceptable to young women, as trust increased after experience and discussion with a clinician. This “skills-based” approach may enhance use of point-of-care tests.

Acknowledgements

Sources of Support: NIH/NIAID/K23 A1063182; NIBIB/1U54 EB007958

Abbreviations

- POC

point-of-care

- BV

bacterial vaginosis

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- TV

Trichomonas vaginalis

- NAAT

nucleic acid amplification test

- CI

confidence interval

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This data was presented as a poster by Marianne Claire Bernard at the Capstone Poster Symposium at the University of Cincinnati. This data was also presented as an oral presentation for the 2011 Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM) annual meeting.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Jill S. Huppert reports that she has received kits/ reagents from Gen-Probe, Inc., and kits/ reagents and honorarium from Genzyme Diagnostics, Inc. However, neither company has had access to the data or to the manuscript under review. There are no other conflicts of interest to report for other authors.

The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jill S. Huppert and Elizabeth A. Hesse. No honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to produce the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jill S. Huppert, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue – MLC 4000, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039, USA, Office: (513) 636-7042, Fax: (513) 636-8844, jill.huppert@cchmc.org.

Elizabeth A. Hesse, Clinical Research Coordinator, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039, USA.

Marianne Claire Bernard, Student Associate, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039, USA.

Justin R. Bates, Data Manager, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039, USA.

Charlotte A. Gaydos, Professor, School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, STD Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, 855 North Wolfe Street, 530 Rangos Building, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Jessica A. Kahn, Associate Professor, Pediatrics, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039, USA.

References

- 1.Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States 2001–2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:864–869. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074e565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bump RC, Buesching WJ., 3rd Bacterial vaginosis in virginal and sexually active adolescent females: evidence against exclusive sexual transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:935–939. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotman RM, Erbelding EJ, Jamshidi RM, Klebanoff MA, Zenilman JM, Ghanem KG. Findings associated with recurrence of bacterial vaginosis among adolescents attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen S, Shafer MA, Moncada J, Campbell CJ, Flinn SD, Boyer CB. Bacterial vaginosis in sexually experienced and non-sexually experienced young women entering the military. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:927–933. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, Stevens C, DeRouen T, Holmes KK. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:819–828. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:585–590. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hitti J, Nugent R, Boutain D, Gardella C, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Racial disparity in risk of preterm birth associated with lower genital tract infection. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:330–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French JI, McGregor JA, Parker R. Readily treatable reproductive tract infections and preterm birth among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.004. discussion 26–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91115-s. discussion 21–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Wijgert JH, Morrison CS, Brown J, et al. Disentangling contributions of reproductive tract infections to HIV acquisition in African Women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:357–364. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a4f695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myer L, Denny L, Telerant R, Souza M, Wright TC, Jr., Kuhn L. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1372–1380. doi: 10.1086/462427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwebke JR, Hillier SL, Sobel JD, McGregor JA, Sweet RL. Validity of the vaginal gram stain for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:573–576. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landers DV, Wiesenfeld HC, Heine RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Predictive value of the clinical diagnosis of lower genital tract infection in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West B, Morison L, Schim van der Loeff M, et al. Evaluation of a new rapid diagnostic kit (FemExam) for bacterial vaginosis in patients with vaginal discharge syndrome in The Gambia. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:483–489. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tebb KP, Paukku MH, Pai-Dhungat MR, Gyamfi AA, Shafer MA. Home STI testing: the adolescent female's opinion. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blake DR, Duggan A, Quinn T, Zenilman J, Joffe A. Evaluation of vaginal infections in adolescent women: can it be done without a speculum? Pediatrics. 1998;102:939–944. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs MM, van der Pol B, Totten P, et al. From the NIH: proceedings of a workshop on the importance of self-obtained vaginal specimens for detection of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:8–13. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815d968d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.pHEM-ALERT [Package Insert] Redmond, WA: Gynex; 2001. In. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy S, Caillouette JC, Faden JS, Roy T, Ramos DE. Improving appropriate use of antifungal medications: the role of an over-the-counter vaginal pH self-test device. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2003;11:209–216. doi: 10.1080/10647440300025523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutman RE, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Blume J. Evaluation of clinical methods for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:551–556. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000145752.97999.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myziuk L, Romanowski B, Johnson SC. BVBlue test for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1925–1928. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.1925-1928.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, Horvath LB, Kuzevska I, Fairley CK. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBlue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1304–1308. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1304-1308.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huppert JS, Hesse E, Kim G, et al. Adolescent women can perform a point-of-care test for trichomoniasis as accurately as clinicians. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:514–519. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.042168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huppert JS, Hesse EA, Bernard MA, et al. Acceptability of self-testing for trichomoniasis increases with experience. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:494–500. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn JA, Bernstein DI, Rosenthal SL, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus self testing in female adolescents. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:408–414. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Second ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WC. Bias in discrepant analysis: when two wrongs don't make a right. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]