Abstract

We assessed whether mothers’ and fathers’ self-reports of acceptance-rejection, warmth, and hostility/rejection/neglect (HRN) of their pre-adolescent children differ cross-nationally and relative to the gender of the parent and child in 10 communities in 9 countries, including China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States (N = 998 families). Mothers and fathers in all countries reported a high degree of acceptance and warmth, and a low degree of HRN, but countries also varied. Mothers reported greater acceptance of children than fathers in China, Italy, Sweden, and the United States, and these effects were accounted for by greater self-reported warmth in mothers than fathers in China, Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, and Thailand and less HRN in mothers than fathers in Sweden. Fathers reported greater warmth than mothers in Kenya. Mother and father acceptance-rejection were moderately correlated. Relative levels of mother and father acceptance and rejection appear to be country specific.

Keywords: parenting, acceptance, rejection, culture

Acceptance of one’s child is a cornerstone of adaptive and positive parenting. For example, a central tenet of Rohner’s (2004) Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory (PARTheory) is that high parental acceptance and low rejection of children are associated with positive child developmental outcomes. Although PARTheory was developed in a Western (U.S.) setting, meta-analyses and reviews of cross-cultural and intra-cultural data generally support the broader applicability of its basic propositions (e.g., Khaleque & Rohner, 2002a; Rohner & Britner, 2002). Two significant aspects still unclear are the degree to which mothers and fathers are similarly accepting and rejecting of their children across cultures and whether and how cultures vary in levels of acceptance and rejection. Most research has examined only maternal acceptance-rejection, or failed to report about mothers and fathers separately (Khaleque & Rohner, 2002a). This study assesses whether mothers and fathers from the same families in 10 communities in 9 countries are similarly accepting and rejecting of their children, and explores country differences in acceptance and rejection.

Acceptance and Rejection

PARTheory describes parental acceptance-rejection as a single continuum. Acceptance is characterized by high levels of parental warmth and low levels of hostility, undifferentiated rejection, and neglect (HRN) of the child, and rejection is characterized by high levels of HRN and low levels of warmth toward the child. However, it is theoretically possible for parents to exhibit high or low levels of acceptance and rejection simultaneously (or serially), and there is empirical support to indicate that acceptance and rejection are distinct constructs (Rohner & Cournoyer, 1994). Consequently, in addition to a total acceptance-rejection scale, in this study we assessed parental warmth (the positive behavior underlying parental acceptance) and hostility/rejection/neglect (the negative behaviors underlying parental rejection) separately across mothers and fathers and across countries.

MacDonald (1992) argued that parental warmth is a universal, species-specific, adaptive form of caregiving that evolved to protect and nurture offspring, and Trivers (1974) described parent-child conflict as an inherent and necessary part of the parent-child relationship because of the competing goals and demands of parents and children. For example, a child may demand more time and energy than a parent is able to provide, thus creating conflict and setting the scene for parental HRN. Therefore, acceptance and rejection are two sides of parenting. Furthermore, parental acceptance and rejection each has long-reaching consequences for child development and adaptive functioning. In Western and non-Western studies alike, children with more accepting and less rejecting parents have higher self-esteem (Haque, 1988; Litovsky & Dusek, 1985) and social competence (Kim, Han, & McCubbin, 2007) and experience fewer mental health, behavioral, and substance abuse problems (Rohner & Britner, 2002; Rohner, Khaleque, & Cournoyer, 2003). Maternal and paternal acceptance also appear to promote more accepting romantic relationships as children reach adulthood (Parmar, Ibrahim, & Rohner, 2008; Varan, Rohner, & Eryuksel, 2008).

If acceptance and rejection are each a part of parenting, their relation to one another is still unresolved. It could be that acceptance-rejection are poles on a single dimension, or it could be that acceptance and rejection are separate (and related?) dimensions. In this investigation, we include acceptance-rejection as a single dimension as well as exploring the behaviors that are characteristic of each end of the continuum (i.e., warmth and HRN) separately. In addition to the issue of the uni- or bi-dimensionality of acceptance and rejection, other methodological issues are associated with its measurement. Historically, acceptance and rejection have been measured using different methods (e.g., observation vs. questionnaire) and raters (e.g., experimenter vs. child vs. parent). Because of the samples and scope of the present study (mothers and fathers in 9 countries), we opted to employ a single parent self-report questionnaire approach. The parents in this study had 7- to 10-year-old children, who may be less reliable reporters of parenting than parents themselves. Parental self-reports reflect the parent’s representation of actual parenting, but may also be colored by the parent’s view of ideal parenting or motivations behind their actions (Paulhus & Vazire, 2007). We employ mother and father socially desirable response patterns as statistical controls to avert such possible biases associated with self-reports (i.e., parents’ tendency to present themselves and their parenting in a positive light).

Cross-National Variation in Acceptance and Rejection

Parents in different nations may have different expectations, values, and beliefs about parenting (Bornstein & Lansford, 2010). Rohner et al. (2003) estimated that about 75% of parents world-wide are warm and loving to their children and the remaining 25% are characterized by at least mild rejection. Studying acceptance and rejection of children in a diverse set of cultural contexts is crucial to advance understanding of the universality of mother and father warmth and rejection of their offspring. The 10 communities in 9 countries selected for inclusion in this study vary by ethnicity, religion, economic indicators, and indices of child well-being. We acknowledge that each sample is only representative of part of the country under study, and we use the country name as shorthand when referring to the community or communities within each.

Few studies have explored cross-national differences in parental acceptance and rejection. Perris et al. (1985), Chung, Zappulla, and Kaspar (2008), and Dwairy (2010) compared mothers and/or fathers across countries. These three studies offer only a small selection of countries, and their results suggest that parental acceptance and rejection vary across western and nonwestern countries as well as within western and non-western countries. The present study expands the base of cross-national comparison and disaggregates and compares maternal and paternal acceptance and rejection. We expected parents from countries where an authoritative parenting style predominates (e.g., Italy, Sweden, and the United States) to be more accepting and warmer than parents from countries where a more authoritarian (or strict) parenting style is more common (e.g., China, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, and Thailand). We also expected parents from countries that stress obedience and conformity in children (e.g., China, Jordan, and Kenya) to score lower on acceptance and higher on HRN than parents from countries that stress child agency and child rights (e.g., Italy, Sweden, and the United States).

Acceptance and Rejection in Mothers vs. Fathers

U.S. American mothers and fathers are known to vary in the degree to which they exhibit accepting and rejecting behaviors. Most U.S. studies point to mothers being more accepting than fathers (e.g., Armentrout & Burger, 1972; Forehand & Nousiainen, 1993; Gamble, Ramakumar, & Diaz, 2007; Tacón & Caldera, 2001; Winsler, Madigan, & Aquilino, 2005). Some non-Western studies support the consistency of this difference (Chung et al., 2008; Gerlsma & Emmelkamp, 1994; Shek, 1998), but some do not (e.g., Chen, Liu, & Li, 2000; Russell & Russell, 1989). Dwairy (2010) reported that across 9 cultural groups fathers were perceived by children as more rejecting and less accepting than mothers. However, the effect sizes were small, statistical controls were not used, and no test was reported for whether or not these mother-father differences were moderated by culture.

Within-family mother-father agreement in relative standing (i.e., correlation) of acceptance and rejection has rarely been studied. Forehand and Nousiainen (1993), DuBois, Eitel, and Felner (1994), and Veneziano (2000, 2003) reported large correlations between mother and father acceptance-rejection. Strong agreement between parents may indicate that they work as a unit. Coparenting refers to the ways that parents relate to each other in the role of parent. Coparenting occurs when individuals have overlapping or shared responsibility for rearing a child and consists of the support and coordination that parental figures exhibit in childrearing. For optimal coparenting, adults should convey to children that there is solidarity, consistency, predictability, and support between parenting figures (Feinberg, 2003; McHale, Lauretti, Talbot, & Pouquette, 2002). If mothers and fathers have strong coparenting, we might expect them to show similar mean levels and have strong correlations between their acceptance and between their rejection of their children.

Acceptance and Rejection of Girls and Boys

Whether parents are differentially accepting and rejecting of their girls and boys is still debated. Findings have been mixed, with some studies reporting that parents are more accepting/less rejecting of girls than boys (Armentrout & Burger, 1972; Chung et al., 2008; Keresteš, 2001; Shek, 2008), some reporting that parents are more accepting/less rejecting of boys than girls (Carter, 1984; Conte, Plutchik, Picard, Buck, & Karasu, 1996), and others reporting no difference in parental acceptance/rejection of girls and boys (Erkan & Toran, 2010; Lila, Garcia, & Gracia, 2007). Exploring child gender differences in a large, diverse, cross-national sample may help to resolve the prevailing ambiguity about child gender effects in the acceptance-rejection literature. For example, it could be that parents are more accepting of girls than boys in some countries but more accepting of boys than girls in other countries.

Even if there are no main effects of child gender, it is still possible that parent gender interacts with child gender. Studies of parent-child relationships rarely investigate the interactions between child gender and parent gender. However, evidence exists that each relationship – mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son – may be unique (Russell & Russell, 1989; Russell & Saebel, 1997; Shek, 1998). Consequently, we include the interactions between parent gender, child gender, and country to determine whether mothers and fathers are similarly accepting and rejecting of their daughters and sons across countries.

This Study

We assessed agreement between mothers and fathers on their self-reported acceptance and rejection of daughters and sons in 9 countries. Agreement was assessed by both relative (rank) order and mean level. Mothers and fathers were recruited within families in adequate numbers to allow comparison within and across countries. Child gender was also collected and analyzed with respect to parent gender so that acceptance and rejection in mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son dyads could be explored cross-nationally.

Method

Participants

Mothers and fathers of 7- to 10-year-old children from 998 families in 10 communities in 9 countries provided data. From a larger sample of 1258 families, we selected the 998 families (79%) with available data from both parents; 998 mothers and 998 fathers. Families were drawn from Shanghai, China (n = 119), Medellín, Colombia (n = 107), Naples and Rome, Italy (n = 176), Zarqa, Jordan (n = 111), Kisumu, Kenya (n = 97), Manila, Philippines (n = 94), Trollhättan/Vänersborg, Sweden (n = 76), Chiang Mai, Thailand (n = 82), and Durham, North Carolina, United States (n = 136). This sample of countries varied greatly on the Human Development Index (ranks of 4 to 128 out of 169), a composite indicator of a country’s status with respect to health, education, and income (UNDP, 2010). To provide a sense of what this range entails, in the Philippines, for example, 23% of the population falls below the international poverty line of less than US$1.25 per day, whereas none of the population reportedly falls below this poverty line in Italy, Sweden, or the United States (UNICEF, 2009). Ultimately, this diversity of sociodemographic and psychological characteristics provided us with an opportunity to examine our research questions in a sample that is more generalizable to the world’s population than single samples, and it provided comparison groups that varied across multiple economic and social dimensions. Finding a universal pattern of parenting across this distinct set of countries would provide meaningful support for a species-specific behavior pattern associated with childrearing.

In addition, in Italy, data were collected from families in 2 communities, Naples and Rome. No differences were found between mother or father acceptance-rejection, warmth, or HRN in Naples and Rome in preliminary tests. Therefore, we combined the communities in this country.

Parents were recruited from schools that served socioeconomically diverse populations in each country. If parents had more than one child in the age range, we enrolled only the first child for whom we received consent forms. Demographic characteristics of mothers, fathers, children, and households by country are presented in Table 1. Mothers averaged 36.75 (SD = 6.10) years, and fathers averaged 40.25 (SD = 6.54) years. Mothers had completed 12.75 (SD = 4.20) years of education, and fathers had completed 12.94 (SD = 4.13) years of education on average. Maternal and paternal ages and educations, respectively, differed across countries. Most mothers were married (87.5%) or unmarried and cohabitating (8.6%). Children averaged 8.27 (SD = .65) years overall, and child age differed across countries. Parents of girls and boys were represented approximately equally overall (51% girls) and in each country subsample. Most (74.8%) children had one or more siblings (or other children) living in the household.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of families in 9 countries

| China | Colombia | Italy | Jordan | Kenya | Philippines | Sweden | Thailand | United States | F/χ2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Mother | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 35.42 | 3.24 | 36.79 | 7.41 | 39.13 | 5.34 | 36.29 | 5.91 | 32.16 | 5.88 | 38.11 | 6.14 | 38.07 | 4.50 | 36.16 | 5.68 | 37.14 | 7.01 | 13.36*** | |

| Education | 13.55 | 2.88 | 10.64 | 5.62 | 12.53 | 4.55 | 13.11 | 2.17 | 10.62 | 3.66 | 13.22 | 3.94 | 13.99 | 2.39 | 12.86 | 4.38 | 14.16 | 4.65 | 10.89*** | |

| % Working | 85 | 49 | 61 | 18 | 74 | 63 | 93 | 88 | 70 | 193.13*** | ||||||||||

| % Married | 100 | 70 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 68 | 88 | 81 | 131.10*** | ||||||||||

| Father | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 37.98 | 3.88 | 40.51 | 8.47 | 42.55 | 5.53 | 41.92 | 5.42 | 39.02 | 6.53 | 40.32 | 7.43 | 40.59 | 5.50 | 39.11 | 6.26 | 39.03 | 7.53 | 7.11*** | |

| Education | 14.00 | 3.07 | 9.90 | 5.34 | 12.54 | 4.33 | 13.18 | 3.14 | 12.16 | 3.58 | 13.67 | 3.73 | 13.84 | 3.06 | 13.20 | 3.74 | 14.19 | 4.38 | 12.21*** | |

| % Working | 98 | 95 | 97 | 94 | 94 | 90 | 97 | 100 | 91 | 18.21* | ||||||||||

| Child | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 8.53 | .65 | 8.22 | .50 | 8.29 | .62 | 8.46 | .50 | 8.46 | .65 | 8.03 | .31 | 7.71 | .46 | 7.66 | .65 | 8.64 | .63 | 35.92*** | |

| % Female | 52 | 56 | 52 | 45 | 62 | 45 | 46 | 50 | 52 | 9.67 | ||||||||||

| Household | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N adults | 2.84 | 1.06 | 2.54 | 1.24 | 2.20 | .62 | 2.57 | 1.19 | 2.95 | 1.40 | 3.77 | 1.91 | 2.00 | .52 | 3.39 | 1.42 | 2.18 | .78 | 25.84*** | |

| N children | 1.25 | .49 | 2.15 | 1.14 | 2.02 | .79 | 3.49 | 1.51 | 3.68 | 1.68 | 2.73 | 1.31 | 2.26 | .74 | 1.74 | .75 | 2.53 | 1.21 | 52.79*** | |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .001.

We chose to study parents of 7- to 10-year-old children because the potentially stressful transition to formal schooling had passed and the culturally distinct stressors sometimes associated with parenting older adolescent children had not yet arrived. Middle childhood normally represents a relatively stable period of parenting.

Procedures

Translation

A procedure of forward- and back-translation was used to ensure the linguistic and conceptual equivalence of measures across languages (see Maxwell, 1996). Translators were fluent in English and the target language. In addition to translating the measures, translators were asked to note items that did not translate well, were inappropriate for the participants, were culturally insensitive, or elicited multiple meanings and to suggest improvements. Site coordinators and the translators reviewed the discrepant items and made appropriate modifications. Measures were administered in Mandarin Chinese (China), Spanish (Colombia and the United States), Italian (Italy), Arabic (Jordan), Dholuo (Kenya), Filipino (the Philippines), Swedish (Sweden), Thai (Thailand), and American English (the United States and the Philippines).

Interviews

Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, schools, or at another location chosen by the participants. Procedures were approved by local IRBs at universities in each participating country, and all parents signed statements of informed consent. Mothers and fathers were given the option of having the questionnaires administered orally (with rating scales provided as visual aids) or completing written questionnaires. Mothers and fathers completed the questionnaires independently. Parents were given modest financial compensation for their participation, families were entered into drawings for prizes, or modest financial contributions were made to children’s schools.

Measures

The Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form (PARQ/Control-SF; Rohner, 2005) was used to measure self-report of the frequency of mother and father parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers each rated 29 items as 1, never or almost never, 2, once a month, 3, once a week, or 4, every day. Based on feedback from pretesting, we modified the original response scale (almost never true, rarely true, sometimes true, almost always true) by quantifying it to reduce the possibility of ambiguous interpretations across cultures. In this study, we did not use 5 items about behavioral control. We used the total acceptance-rejection scale, which is computed as the sum of the items for warmth-affection (reversed), hostility-aggression, rejection, and neglect-indifference (high score = more rejection). In addition, based on Rohner and Cournoyer’s (1994) analysis of the factor structure of the PARQ scale in 8 cultural groups, 2 subscales were derived, measuring parental warmth and hostility/rejection/neglect (HRN). Warmth was computed as the average of 8 items from the warmth-affection subscale, such as “I make my child feel wanted and needed.” HRN was computed as the average of 16 items from the hostility-aggression, rejection, and neglect-indifference subscales such as, “I punish my child severely when I am angry.” and “I pay no attention to my child when (s)he asks for help.” We computed the warmth and HRN subscales as means instead of sums because there were different numbers of items in these scales and using means put them in the same metric, making them directly comparable.

In a meta-analysis of the reliability of the PARQ using data from 51 studies in 8 countries, Khaleque and Rohner (2002b) concluded that α coefficients exceeded .70 in all groups, effect sizes were homogenous across groups, and convergent and discriminant validity were demonstrated (Rohner, 2005). In the present study, correlations between the warmth and HRN subscales were r(993) = -.41, p < .001, for mothers (83% of their variance unshared), and r(995) = -.32, p < .001, for fathers (90% of their variance unshared), supporting the bidimensionality of warmth and HRN. Internal consistency (α) reliabilities across all countries were .81 for mother acceptance-rejection, .75 for mother warmth and mother HRN, .79 for father acceptance-rejection and father warmth, and .73 for father HRN.

The 13-item Social Desirability Scale-Short Form (SDS-SF; Reynolds, 1982) was used to assess parents’ social desirability bias. Statements like “I’m always willing to admit when I make a mistake.” were rated as True or False. Reliability (α) of the SDS-SF is .76, and the correlation with the full-length SDS .93 (Reynolds, 1982).

Analytic Plan

Analyses proceeded in two stages. First, repeated-measures linear mixed models, with parent gender as within-subjects and child gender, country, and the 2- and 3-way interactions between parent gender, child gender, and country as between-subjects fixed effects, tested for differences between mothers and fathers in total acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN. The covariance structure was modeled as heterogeneous compound symmetry, accounting for the likelihood that mothers’ and fathers’ total acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN would be correlated, but allowing mothers’ and fathers’ variances to differ. Results are presented with controls for mothers’ and fathers’ ages, educations, and social desirability scores, and child age. For country main effects, we compared each country to the grand mean (deviation contrast) because we were less interested in individual country contrasts and more interested in the relative ordering of countries. (Unfortunately, effect sizes are not available in repeated-measures linear mixed models.) We controlled for parental age and education because parents who were older, and those with higher levels of education, were more accepting, rs(1960-1970) = -.15 and -.13, ps < .001, warmer, rs(1974-1986) = .13 and .08, ps < .001, and reported lower HRN, rs(1971-1982) = -.12 and -.12, ps < .001. We controlled for social desirability because it was associated with higher acceptance, r(1970) = -.24, p < .001, higher warmth, r(1986) = .10, p < .001, and lower HRN, r(1982) = -.27, p < .001. We controlled child age because parents were warmer toward younger children, r(1994) = -.06, p = .006. Using the procedure outlined above, linear mixed modeling is analogous to repeated-measures analysis of covariance (R-M ANCOVA), but linear mixed models have the ability to control for covariates that vary across the within-subjects factor (e.g., mother/father education).

Second, the partial correlations between maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN were computed using structural equation models, controlling for parents’ ages, educations, and social desirability scores, and child age. Equivalence of mother-father correlations across countries was tested using multiple group models in AMOS 18 (Arbuckle, 2009). Models in which covariances (i.e., correlations between mother and father scores) were constrained to be equal across the 9 countries were compared to models in which the covariances were free to vary across the 9 countries. Following Cheung and Rensvold (2002), if the differences in chi-square values for the 2 models were nonsignificant and the change in CFI (an incremental model fit index) was .01 or less, we concluded that mother-father correlations were similar across countries. If the differences in chi-square values for the 2 models were significant and/or the change in CFI was greater than .01, we attempted to improve the change in model fit by releasing the covariance for one or more countries.

Results

Gender and Country Similarities and Differences in Parental Acceptance and Rejection

Total Acceptance-Rejection

In total parental acceptance-rejection models, the Parent gender by Country interaction, F(8, 933.56) = 4.45, p < .001, and the main effects of country, F(8, 935.95) = 46.89, p < .001, and parent gender, F(8, 1100.78) = 12.06, p = .001, were significant. Neither the main effect of child gender nor any of the other 2- or 3-way interactions were significant. To decompose the Parent gender by Country interaction, we re-analyzed the Child gender by Parent gender model within each country and the Child gender by Country model within mothers and fathers. Within country, there were several significant main effects of parent gender (Table 2), but no main effects of child gender. Mothers in China, Italy, Sweden, and the United States rated themselves as more accepting than fathers rated themselves. Mothers and fathers in Colombia, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, and Thailand did not differ in self-reported acceptance-rejection. Within mothers and fathers, there were significant main effects of country, F(8, 971) = 36.22, p < .001, and F(8, 952) = 24.85, p < .001, respectively. As seen in Table 2, mothers and fathers in China, Jordan, and Kenya rated themselves as less accepting than the grand mean, and mothers and fathers in Colombia, Italy, Sweden, and the United States rated themselves as more accepting than the grand mean. Mothers’ and fathers’ ratings in the Philippines and Thailand did not differ from the grand mean.

Table 2.

Total Acceptance-Rejection: Descriptive statistics, country deviation from the grand mean within mothers and fathers, main effects of parent gender within country, and correlations between mothers and fathers

| Mother

|

Father

|

Mother vs. Father Fa | ra | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | |||

| China | 35.18 | 6.27 | 6.34*** | 37.80 | 7.29 | 9.66*** | 10.10** | .04 |

| Colombia | 29.74 | 5.74 | -5.63*** | 29.88 | 5.20 | -6.18*** | .65 | .16 |

| Italy | 29.61 | 4.36 | -5.66*** | 31.40 | 5.67 | -3.31*** | 13.26*** | .23** |

| Jordan | 36.02 | 8.43 | 7.68*** | 35.21 | 8.11 | 3.51*** | .12 | .36*** |

| Kenya | 38.54 | 8.23 | 8.95*** | 35.60 | 7.33 | 3.79*** | .03 | .13 |

| Philippines | 31.61 | 5.20 | -.25 | 32.58 | 7.20 | .12 | 1.49 | .38*** |

| Sweden | 28.75 | 4.88 | -6.02*** | 31.35 | 4.86 | -2.96*** | 8.33** | .09 |

| Thailand | 33.15 | 5.93 | .65 | 33.48 | 6.35 | .86 | 1.38 | .30* |

| United States | 28.68 | 5.38 | -6.90*** | 29.66 | 5.32 | -5.73*** | 4.39* | .31*** |

|

| ||||||||

| Grand Mean | 32.16 | 6.93 | -- | 32.88 | 6.94 | -- | -- | .39*** |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Controlling for parental age, education, and social desirability, and child age.

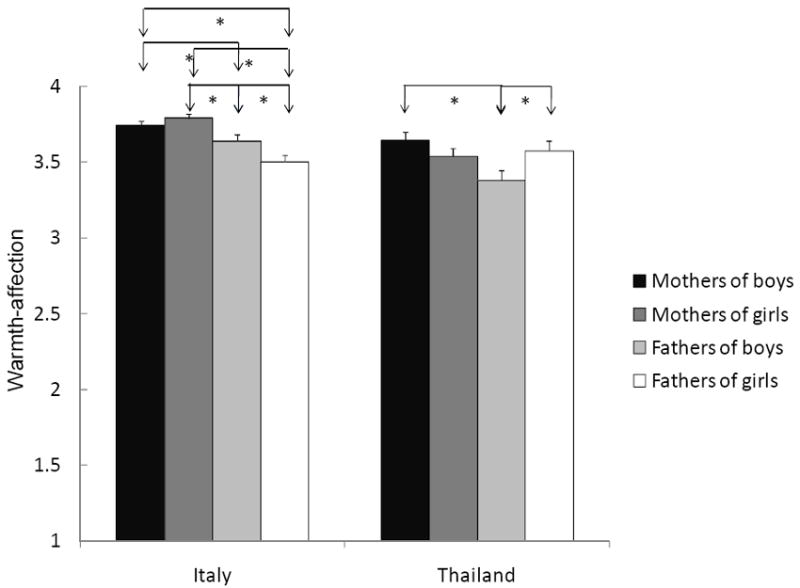

Warmth

In parental warmth models, the Child gender by Parent gender by Country interaction was significant, F(8, 942.64) = 2.40, p = .014, as was the Parent gender by Country interaction, F(8, 946.40) = 5.28, p < .001. To decompose these interactions, we re-analyzed the Child gender by Parent gender models within each country and the Child gender by Country models within mothers and fathers. In Italy and Thailand, there were significant Child gender by Parent gender interactions, F(1, 170.73) = 7.99, p = .005, and F(1, 77.70) = 7.43, p = .008, respectively. The differences between the six possible comparisons of mother-father-daughter-son pairs are presented in Figure 1. In Italy, each dyad type (mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, father-son) was unique except for mother-daughter and mother-son pairs, to whom mothers rated being equally warm. In Thailand, fathers of boys reported themselves to be less warm than mothers of boys and fathers of girls rated themselves, but none of the other pairs of dyads’ ratings differed.

Figure 1.

Warmth: Parent gender by Child gender interactions in Italy and Thailand

* p ≤ .05.

Within country, there were also several significant main effects of parent gender (Table 3), but no main effects of child gender. Overall, mothers in China, Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, and Thailand rated themselves as warmer than fathers rated themselves, and fathers in Kenya rated themselves as warmer than mothers rated themselves. Mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of warmth did not differ in Colombia, Jordan, or the United States.

Table 3.

Warmth: Descriptive statistics, country deviation from the grand mean within mothers and fathers, main effects of parent gender within country, and correlations between mothers and fathers

| Mother

|

Father

|

Mother vs. Father Fa | ra | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | |||

| China | 3.37 | .44 | -10.33*** | 3.07 | .55 | -14.05*** | 21.15*** | .02 |

| Colombia | 3.85 | .28 | 6.63*** | 3.86 | .32 | 7.60*** | .06 | -.06 |

| Italy | 3.76 | .25 | 3.31*** | 3.57 | .39 | -.66 | 34.45***b | .18* |

| Jordan | 3.59 | .46 | -2.72** | 3.57 | .46 | -.44 | .63 | .38*** |

| Kenya | 3.35 | .50 | -7.66*** | 3.44 | .47 | -3.31*** | 4.48* | .22* |

| Philippines | 3.82 | .23 | 3.76*** | 3.69 | .35 | 2.46* | 12.62*** | .31** |

| Sweden | 3.87 | .22 | 4.77*** | 3.75 | .30 | 3.68*** | 5.13* | .14 |

| Thailand | 3.57 | .38 | -2.54* | 3.50 | .44 | -1.94 | 4.06*b | .15 |

| United States | 3.84 | .29 | 5.33*** | 3.79 | .29 | 5.90*** | 3.51 | .18* |

|

| ||||||||

| Grand Mean | 3.67 | .40 | -- | 3.58 | .46 | -- | -- | .34*** |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Controlling for parental age, education, and social desirability, and child age.

See Figure 1 for a Parent gender by Child gender interaction in this country.

Finally, for mothers and fathers separately, there were significant main effects of country, F(8, 975) = 33.24, p < .001, and F(8, 962) = 38.07, p < .001, respectively, but no main effects for child gender. As seen in Table 3, mothers in China, Jordan, Kenya, and Thailand reported lower warmth than the grand mean, and mothers in Colombia, Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, and the United States reported higher warmth than the grand mean. Similarly, fathers in China and Kenya reported lower warmth than the grand mean, and fathers in Colombia, the Philippines, Sweden, and the United States reported higher warmth than the grand mean. Ratings of fathers in Italy, Jordan, and Thailand did not differ from the grand mean.

Hostility/rejection/neglect

In parental HRN models, the Parent gender by Country interaction, F(8, 964.76) = 3.40, p = .001, and the main effect of country, F(8, 971.36) = 23.57, p < .001, were significant. No other 2- or 3-way interactions were significant, nor were main effects of child gender or parent gender. To decompose the Parent gender by Country interaction, we re-analyzed the Child gender by Parent gender model within each country and the Child gender by Country model within mothers and fathers. Within country, there was one significant main effect of parent gender for Sweden (Table 4), indicating that mothers and fathers reported similar levels of HRN overall except in Sweden. Within mothers and fathers, there were significant main effects of country, F(8, 971) = 21.92, p < .001, and F(8, 959) = 9.77, p < .001, respectively. As seen in Table 4, mothers in Colombia, Italy, Sweden, and the United States reported lower HRN of their children than the grand mean, and mothers in China, Jordan, and Kenya reported higher HRN of their children than the grand mean. Mothers in the Philippines and Thailand did not differ from the grand mean in their ratings. Similarly, fathers in Colombia, Italy, and the United States reported lower HRN of their children than the grand mean, and fathers in China, Jordan, and Kenya reported higher HRN of their children than the grand mean. Fathers in the Philippines, Sweden, and Thailand did not differ from the grand mean.

Table 4.

Hostility/Rejection/Neglect: Descriptive statistics, country deviation from the grand mean within mothers and fathers, main effects of parent gender within country, and correlations between mothers and fathers

| Mother

|

Father

|

Mother vs. Father Fa | ra | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | M | SD | Country vs. Grand Mean ta | |||

| China | 1.39 | .27 | 2.28* | 1.40 | .28 | 3.20*** | .49 | .23* |

| Colombia | 1.28 | .28 | -3.13** | 1.30 | .23 | -2.92** | .69 | .21* |

| Italy | 1.23 | .20 | -5.19*** | 1.26 | .25 | -4.53*** | 1.16 | .21** |

| Jordan | 1.56 | .40 | 7.63*** | 1.48 | .37 | 4.12*** | 1.36 | .36*** |

| Kenya | 1.59 | .36 | 6.17*** | 1.44 | .35 | 2.29* | 1.07 | .15 |

| Philippines | 1.39 | .28 | 1.86 | 1.38 | .36 | 1.79 | .06 | .20 |

| Sweden | 1.23 | .24 | -4.96*** | 1.33 | .23 | -1.47 | 5.11* | .04 |

| Thailand | 1.36 | .27 | -.50 | 1.35 | .32 | -.02 | .00 | .32** |

| United States | 1.22 | .24 | -5.76*** | 1.25 | .24 | -3.81*** | 2.23 | .28*** |

|

| ||||||||

| Grand Mean | 1.35 | .31 | -- | 1.34 | .30 | -- | -- | .32*** |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Controlling for parental age, education, and social desirability, and child age.

Within-Family Correlations between Parents’ Acceptance and Rejection across Country

We tested whether mothers’ and fathers’ total acceptance-rejection scales, mothers’ and fathers’ warmth subscales, and mothers’ and fathers’ HRN subscales were related similarly across countries using multiple-group models. The difference in chi-square value for unconstrained and constrained multiple-group models of the total acceptance-rejection scale was nonsignificant, Δχ2(8) = 13.50, p = .096, ΔCFI = .004, indicating that the correlations between mother and father acceptance-rejection ratings were similar across countries (Table 2). Differences in chi-square values for unconstrained and constrained multiple-group models were significant for warmth, Δχ2(8) = 25.35, p = .001, ΔCFI = .010, and HRN, Δχ2(8) = 27.30, p = .001, ΔCFI = .011, indicating that one or more countries had significantly different mother-father rating correlations. Following the general tests, we attempted to improve the change in model fit by releasing the path for one country at a time. Once the path coefficient for Jordan was released, the change in model fit was no longer significant for warmth, Δχ2(7) = 13.94, p = .052, ΔCFI = .004, or HRN, Δχ2(7) = 9.43, p = .223, ΔCFI = .002. The mother-father rating correlations for Jordan were higher than those in the other countries (Tables 3 and 4). Overall, mothers and fathers in the same families were moderately concordant in their acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN, but mother-father associations were even stronger in Jordan than in the other countries for warmth and HRN.

Discussion

This study identified patterns of parental acceptance and rejection of middle childhood youth that varied across mothers and fathers of daughters and sons and across countries. We discuss the findings for country, parent gender, and child gender in turn.

Acceptance and Rejection across Countries

Mothers and fathers in the communities we studied reported high acceptance and warmth and low rejection and HRN of their children in all 9 countries. In fact, only 1.5% of mothers and 3.5% of fathers rated their warmth toward their children in the lower half of the possible distribution, and fewer than 1% of both mothers and fathers rated their total acceptance-rejection and HRN in the upper half of the possible distribution. Despite the overwhelmingly high levels of acceptance and low levels of rejection across all countries, and despite our use of statistical controls for parental age, education, and social desirability, and child age, some systematic differences between countries emerged. Here, we briefly profile each country. When we refer to levels of acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN below, they are relative to the grand mean of the countries in this study. Therefore, if a country is described as high in HRN, it is high only relative to other countries we studied, not high in absolute terms.

China

Chinese parents rated themselves as relatively low in acceptance and warmth (with mothers rating themselves as more accepting and warmer than fathers) and high, relative to other countries, in HRN. In an analysis of the socialization of Chinese children, Ho (1986) differentiated between the parenting of, and expectations for behavior of, preschool and school-aged children. Preschool children are parented in a lenient, almost indulgent manner by their mothers (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003). In contrast, school-aged children are expected to be controlled and disciplined because of the pressure from an indefatigable academic competition that starts with high intensity right from primary schools (Wang & Chang, 2009). According to Wang and Chang (2008), Chinese parents exercise high parental control especially or almost exclusively in the academic domain, whereas both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting attitudes in urban China at least are more progressive than authoritarian (Chang, Chen, & Ji, 2011). In Chinese parenting, there also seems to be a distinction in the expression of warmth and control between psychological or affective expressions and material and physical means, with the latter being more expressed than the former (Wang & Chang, 2008). The period of childhood (7-10 years) covered in the present study may be characterized by relatively lower parental warmth and higher HRN partly because parenting at this age started to focus on academic issues and partly because the Rohner scale used in the present study tapped mainly affective and psychological expression. Future studies may employ Chinese measures of parental warmth and control (e.g., Wang & Chang, 2008) that separate psychological from material means of parenting and assess academic control separately.

Colombia

Colombian parents rated themselves as relatively high in acceptance and warmth and low in HRN. These results are in agreement with previous findings supporting similarities between Colombian mothers and fathers in terms of adolescents’ reported parental acceptance (Ripoll-Núñez & Alvarez, 2008), self-reports of parenting quality (Gómez, 2006), and both parent and adolescent reports of warm and supportive parent-adolescent relationships (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007; Ripoll-Núñez, Carrillo, & Castro, 2009). Colombia is traditionally described as a collectivist culture where authoritarian parenting predominates (Cardona, Nicholson, & Fox, 2000), and where gender roles influence parenting (i.e., traditionally fathers were the main economic providers and mothers were the primary source of care for the entire family and had the responsibility for rearing younger children; Ripoll-Núñez & Alvarez, 2008). However, contemporary Colombian parents have been described as holding more progressive views (Di Giunta, Uribe Tirado, & Araque Márquez, 2011; Gómez, 2006). In the last 20 years, women’s increased participation in the work force and high levels of education, and men’s increasing participation with their children may have led to more authoritative parenting styles (Gómez, 2006). Both mothers and fathers rate their parenting role more positively than their work and marital roles (Gómez, 2006), indicating a strong focus on parenting.

Italy

Italian mothers and fathers rated themselves as relatively high in acceptance (with mothers higher than fathers), mothers rated themselves as relatively high in warmth (and higher than fathers), and both parents rated themselves as relatively low in HRN. Italian maternal style is often described as exceedingly warm, protective, and family focused (Bombi et al., 2011; Emiliani & Molinari, 1995), while paternal style is considered to be stricter and more authoritarian (Gandini & Edwards, 2000). Some studies support similar beliefs about parenting and similar parental styles between Italian mothers and fathers (Confalonieri et al., 2010; Venuti & Senese, 2007). In particular, both Italian mothers and fathers assign importance to children’s emerging social skills and to dyadic affect-laden exchanges in which parents and their children can experience physical and emotional closeness, warmth, and security (Axia, Bonichini, & Moscardino, 2003; Senese, Poderico, & Venuti, 2003). Likewise, Italian mothers believe the key task for a parent is to take care of children and to rear them in a safe and protective family environment (Carugati, Emiliani, & Molinari, 1990; Edwards, Gandini, & Giovannini, 1993).

Jordan

Jordanian mothers rated themselves relatively low in warmth, and both parents rated themselves as relatively low in acceptance and high in HRN, compared to the other countries. Jordanian mothers’ and fathers’ warmth and mothers’ and fathers’ HRN were also more highly correlated than in other countries. This is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by the Ministry of Labor and Social Development in Jordan (Nimer & Samara, 1990) showing high consistency between mothers’ and fathers’ child rearing and discipline styles. Dwairy (2010) found Jordanian mothers and fathers to be lower in acceptance and higher in rejection than other cultural groups. Ghazwi and Nock (1989) investigated parental beliefs about child obedience and parental control over children in 100 Muslim and 100 Christian male heads of household (presumably fathers) in Jordan. The authors suggested that the traditional Muslim view is that “the child is to be protected and cherished, but he is also expected to return complete obedience and subject his will to that of his parents” (p. 368). Furthermore, in a study conducted by Al Hassan and De Baz (2010) Jordanian mothers listed honesty, politeness, good habits, respecting elders, and obedience as the main values they would like to instill in their children. Jordanian mothers ranked assertiveness and independence 19th and 20th, respectively, out of 26 values suggesting that they encourage conformity over child agency. Our findings about warmth and HRN may reflect these cultural and religious beliefs (Al-Hassan & Takash, 2011).

Kenya

Kenyan mothers and fathers rated themselves as relatively low in acceptance and warmth and high in HRN compared to parents in the other countries. Kenya was the only country where fathers rated their warmth higher than mothers. Oburu (2011) noted that Luo (the ethnic group from which our Kenyan sample was drawn) mothers and fathers have diverging parenting responsibilities. Mothers are responsible for all aspects of childrearing. Kenyan mothers may report lower warmth with their children than fathers because they are tasked with handling the most challenging aspects of childrearing, whereas fathers can choose when and how to interact with their children. Ainsworth (1967) observed about mother-child relationships in Uganda that warm and affectionate interactions were infrequent, but most mother-child dyads had secure attachments. Oburu and Palmerus (2003) and Whiting and Whiting (1975) suggested that amongst the Luo and Gusii ethnic groups living in Western parts of Kenya (the same geographical region from which the present participants were drawn), open displays of affection are viewed by parents as ineffective parenting techniques that could even make good children disobedient. Instead, Kenyan parents display their affection by giving tangible benefits such extra food, material goods, and privileges. These observations suggest that the lower level of warmth found in Kenyan mothers in this study should be treated with caution because Kenyan mothers may simply express their love and affection for their children in different ways than other cultures.

Philippines

Filipino mothers and fathers rated themselves as relatively high in warmth (with mothers significantly higher than fathers), and average in total acceptance-rejection and HRN. Filipino parents are generally considered to be strongly family oriented (Alampay & Jocson, 2011), and, in general, childrearing among Filipinos has been described as affectionate, indulgent, and supportive even in the context of high expectations for children to obey parental authority (Medina, 2001; Ventura, 1981). Supporting our findings, Filipino children have reported their mothers to be more nurturant and involved than their fathers (Carunungan-Robles, 1986). Mothers are also perceived to give directives and organize children’s activities more than fathers, but children did not perceive differences in punitiveness between their parents (Carunungan-Robles, 1986).

Sweden

Swedish mothers and fathers rated themselves as relatively high in acceptance and warmth (with mothers significantly higher than fathers), and Swedish mothers also rated themselves as relatively low in HRN (and lower than fathers). Perris et al. (1985) also found that Swedish mothers were more accepting than Italian, Danish, and Australian mothers, and Swedish fathers were less rejecting than Italian and Australian fathers. Sweden has a unique social structure that promotes gender equality. For example, Swedish laws provide similar childcare benefits to mothers and fathers (e.g., paid time off from work following childbirth; Haas, 1990). Mothers still take most of the parental leave, but fathers take about 21% of the total days at home following childbirth (Ljungberg, 2006). Swedish couples with children describe their parenting as equal, but studies reveal that mothers and fathers still adopt traditional roles in the family (Bäck-Wiklund & Bergsten, 1997; Magnusson, 2006), which could explain why Swedish mothers described themselves as warmer and less HRN than fathers. The low level of HRN reported by both mothers and fathers could reflect Swedish promotion of child agency. Both mothers and fathers in Sweden report progressive parenting attitudes (Sorbring & Gurdal, 2011), and Sweden strongly endorses the child rights perspective that children’s rights are equal to those of adults (Carlson & Earls, 2001).

Thailand

Thai mothers rated themselves as relatively low in warmth (but significantly warmer than fathers), and mothers and fathers rated themselves as average in all other ways. Thai families are traditionally described as hierarchical, with children encouraged to be compliant and obedient. However, Tapanya (2011) and Rhucharoenpornpanich et al. (2010) found that Thai mothers and fathers reported higher progressive than authoritarian parenting attitudes. Thai fathers tend to be less involved in childcare than Thai mothers (Tulananda, Young, & Roopnarine, 1994; Tulananda & Roopnarine, 2001), and mothers discipline their children more than fathers (Tulananda & Roopnarine, 2001). Pinyuchon and Gray (1997) observed that Thai women have total power for decision-making about children. Perhaps having this power and all of the responsibility that comes with it leads mothers to feel somewhat less warm with their children than mothers in other countries who share some of the more challenging parenting responsibilities of preadolescent children with their spouses.

United States

U.S. mothers and fathers rated themselves as relatively high in acceptance (with mothers rating themselves as more accepting than fathers) and relatively high in warmth and low in HRN (with mothers and fathers rating themselves similar to one another). Parents in the United States have been described as progressive in their parenting attitudes (Lansford et al., 2011), and U.S. mothers report high levels of investment in the parental role (Bornstein et al., 1998). Many studies on U.S. samples have found that mothers are more accepting than fathers (Armentrout & Burger, 1972; Forehand & Nousiainen, 1993; Gamble et al., 2007; Tacón & Caldera, 2001; Winsler et al., 2005), and like our study mothers and fathers in Russell and Russell’s (1989) study were rated as equally warm on average.

These country profiles indicate some common and some unique cultural influences that could lead to different levels of acceptance-rejection, warmth, and HRN in mothers and fathers. One common influence is that the samples were drawn from urban locales in nearly all countries, so the levels of maternal education and workforce participation were relatively high across most countries (Table 1). Some country-specific influences are also in evidence. The parenting practices traditionally directed toward younger and older children in China, the potential effects of Muslim religious practices in Jordan, and the effects of legislation to protect child rights in Sweden could help to explain the ordering of mothers and fathers on acceptance and rejection in these countries. National differences are rarely explained by a single socializing force. Despite the sometimes striking differences between countries in predominant demographic, religious, psychological, and economic conditions, nearly all mothers and fathers in these samples characterized themselves as high in acceptance and warmth toward their children and low in hostility, rejection, and neglect of their children.

Agreement between Mothers and Fathers

Mothers in the communities we studied reported greater acceptance of children than fathers in four of 9 countries. This pattern appeared to be driven by warmth because there was only one mother-father difference in HRN (Sweden), but mothers reported more warmth than fathers in five countries and less warmth in only one country. We could not locate another study where fathers rated themselves or were rated by others as significantly warmer than mothers on average. The overall trend across all 9 countries was for more accepting and warmer mothers than fathers, but this effect was moderated by country.

The moderate levels of agreement we found between mother and father acceptance, mother and father warmth, and mother and father HRN may indicate that mothers and fathers have somewhat differing roles in the family. Parents may be alike in their attitudes about parenting, but compensate for one another by assuming family roles that the other parent does not assume, do well, or enjoy. For example, mothers might more often assume the main responsibility for grooming, meal preparation, and tending to physical and psychological wounds, and fathers might more often assume the main responsibility for helping with homework, arbitrating sibling disputes, and teaching sports. These different parenting tasks may lead mothers and fathers to hold somewhat different views of their own acceptance and rejection of their children. It may be adaptive for parents to complement one another because it plays to their parenting strengths. Therefore, nonidentical moderate levels of agreement found between parents may actually be more ideal from a childrearing perspective.

Acceptance and Rejection of Girls and Boys

Across the communities we studied in the 9 countries, parents reported being similarly accepting, warm, and HRN with their girls and boys. Furthermore, parent gender did not interact with child gender, except for warmth in Italy and Thailand. In Italy, mothers of boys and mothers of girls reported they were equally warm, but all 5 other comparisons of parent-child dyads differed (see Figure 1). In Thailand, mothers of boys and fathers of girls reported they were warmer than fathers of boys. These specific differences in parenting indicate that there is no universal difference in parental treatment of girls and boys. Differential treatment of girls and boys appears to be moderated by cultural practices.

Limitations

As with most samples, ours are limited in generalizability. Although we were able to examine mothers and fathers from the same families in 10 communities in 9 countries, we were not able to include other countries and we were only able to sample school-based families of children in a narrow age range (7-10 years), and mainly from one urban area in each country. There may be within-country regional differences in acceptance and rejection, with urban parents typically reporting more acceptance and less rejection than rural parents (Erkan & Toran, 2010; Keresteš, 2001). Interparental agreement in terms of mean and relative levels could differ in parents of younger or older children as it could in parents married for different lengths of time. We also limited our analyses to those families in which both mother and father provided data. Our samples included some separated and divorced parents, but they were in the minority. We assume greater disagreement in samples with separated or divorced parents because parental separation or divorce often (but not always) elicit more disagreements or conflicts about childrearing as well as less involvement of one or both parents with the child. Maternal and paternal acceptance and rejection were self-reported. Parents’ perceptions of their own parenting may not match their behaviors or others’ perceptions (Bornstein, Cote, & Venuti, 2001; Sessa, Avenevoli, Steinberg, & Morris, 2001). However, self-perceptions of parenting are important in their own right, and we controlled for parental age, education, and social desirability bias to offset these limitations. Finally, due to concerns about the cross-cultural interpretation of the original PARQ response scale, we altered it to be more concrete. Although we believe this change was necessary, it alters the scale in unknown ways, limiting this study’s comparability with others using the traditional response scale.

Future Directions and Conclusions

Going forward, our results suggest that researchers should next explore whether cultural differences in acceptance and rejection have implications for later child development. Furthermore, whether high acceptance and warmth and low rejection and HRN are uniformly related to positive child outcomes across cultures, or whether cultural normativeness of acceptance and rejection moderate the effects of parental acceptance and rejection on child outcomes are open questions.

Overall, this study contributes to the cross-national database on mother and father acceptance and rejection. All parents in our study reported overwhelmingly high love and care for their children. Still, we found differences between countries as well as differences between mothers and fathers and mother and father self-reported treatment of girls and boys that were moderated by country. Future studies should explore parental acceptance and warmth and rejection and HRN in other countries as well as from other points of view (e.g., child reports). Despite the presumptive universality of the effects of acceptance and rejection (Khaleque & Rohner, 2002a; Rohner & Britner, 2002), the relative experience of acceptance and rejection in mothers and fathers appears to be country specific.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who participated in this research.

Funding This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant RO1-HD054805]; and the Fogarty International Center [grant RO3-TW008141]; and was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD. Kenneth A. Dodge is supported by Senior Scientist award 2K05 DA015226 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Patrick S. Malone is supported by grant K01DA024116 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Contributor Information

Diane L. Putnick, Child and Family Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, USA

Marc H. Bornstein, Child and Family Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, USA

Jennifer E. Lansford, Duke University, USA

Lei Chang, Chinese University of Hong Kong, China.

Kirby Deater-Deckard, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, USA.

Laura Di Giunta, Rome University ‘La Sapienza,’ Italy.

Sevtap Gurdal, University West, Sweden.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University, USA

Patrick S. Malone, University of South Carolina, USA

Paul Oburu, Maseno University, Kenya.

Concetta Pastorelli, Rome University ‘La Sapienza,’ Italy.

Ann T. Skinner, Duke University, USA

Emma Sorbring, University West, Sweden.

Sombat Tapanya, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Liliana Maria Uribe Tirado, Rome University ‘La Sapienza,’ Italy and Universidad San Buenaventura, Colombia.

Arnaldo Zelli, University of Rome ‘Foro Italico,’ Italy.

Liane Peña Alampay, Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines.

Suha M. Al-Hassan, Hashemite University, Jordan

Dario Bacchini, Second University of Naples, Italy.

Anna Silvia Bombi, Rome University ‘La Sapienza,’ Italy.

References

- Ainsworth MDS. Infancy in Uganda. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Alampay LP, Jocson RM. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in the Philippines. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:163–176. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hassan O, De Baz T. Childrearing values of mothers in Jordan. Paper presented at the Education in a Changing World Conference; The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan. 2010. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hassan S, Takash H. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Jordan. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:142–151. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 18 User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Armentrout JA, Burger GK. Children’s reports of parental child-rearing behavior at five grade levels. Developmental Psychology. 1972;7:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Axia V, Bonichini S, Moscardino U. Dalle narrative parentali ai dati quantitativi. Etnoteorie parentali in famiglie italiane e nigeriane immigrate in Italia [From parental narratives to quantitative data. Parental etnotheories in Italian families and Nigerian families who immigrated in Italy] In: Poderico C, Venuti P, Marcone R, editors. Diverse culture, bambini diversi? Milano: Unicopli; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bäck-Wiklund M, Bergsten B. Det moderna föräldraskapet. En studie av familj och kön i förändring [Modern parenting A study of family and gender in transformation] Stockholm: Natur och kultur; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bombi AS, Pastorelli C, Bacchini D, Di Giunta L, Miranda MC, Zelli A. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Italy. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:129–141. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Venuti P. Parenting beliefs and behaviors in northern and southern groups of Italian mothers of young infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:663–675. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes OM, Azuma H, Galperin C, Maital S, Ogino M, Painter K, Pascual L, Pecheux M-G, Rahn C, Toda S, Venuti P, Vyt A, Wright B. A cross-national study of self-evaluations and attributions in parenting: Argentina, Belgium, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, and the United States. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:662–676. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Lansford JE. Parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. The handbook of cross-cultural developmental science Volume 1 Domains of human development across cultures. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona PG, Nicholson BC, Fox RA. Parenting among Hispanic and Anglo-American mothers with young children. Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;40:357–365. doi: 10.1080/00224540009600476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Earls F. The child as citizen: Implications for the science and practice of child development. International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development Newsletter, 2. 2001;38:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JA. Maternal acceptance of black and white school-age boys and girls. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1984;146:427–428. [Google Scholar]

- Carugati F, Emiliani F, Molinari L. Being a mother is not enough: Theories and images in the social representations of childhood. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale. 1990;3:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Carunungan-Robles A. Perceptions of parental nurturance, punitiveness, and power by selected Filipino primary school children. Philippine Journal of Psychology. 1986;19:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Chen B-B, Ji LQ. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in China. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:102–115. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge K, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Li D. Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:401–419. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Zappulla C, Kaspar V. Parental warmth and socio-emotional adjustment in Brazilian, Canadian, Chinese, and Italian children: A cross-cultural perspective. In: Ramirez RN, editor. Family relations, issues, and challenges. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2008. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Confalonieri E, Bacchini D, Olivari MG, Affuso G, Tagliabue S, Miranda MC. Adolescenti e stili educativi genitoriali: quale percezione? [Adolescents and parenting styles: which perceptions?] Psicologia dell’educazione. 2010;1:9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Conte HR, Plutchik R, Picard S, Buck L, Karasu TB. Gender differences in recalled parental childrearing behaviors and adult self-esteem. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1996;37:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giunta L, Uribe Tirado LM, Araque Márquez LA. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Colombia. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:116–128. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Eitel SK, Felner RD. Effects of family environment and parent-child relationships on school adjustment during the transition to early adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Dwairy M. Parental acceptance-rejection: A fourth cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP, Gandini L, Giovannini D. The contrasting developmental timetables of parents and preschool teachers in two cultural communities. In: Harkness S, Super C, editors. Parental cultural belief systems. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 270–288. [Google Scholar]

- Emiliani F, Molinari L. Rappresentazioni e affetti [Representations and affects] Milano: Raffaello Cortina; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Erkan S, Toran M. Child acceptance-rejection behaviors of lower and upper socioeconomic status mothers. Social Behavior and Personality. 2010;38:427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Nousiainen S. Maternal and paternal parenting: Critical dimensions in adolescent functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;7:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble WC, Ramakumar S, Diaz A. Maternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: An examination of Mexican-American parents of young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:72–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gandini L, Edwards C. Bambini: The Italian approach to infant/toddler care. New York: Teachers College Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlsma C, Emmelkamp PMG. How large are gender differences in perceived parental rearing styles?: A meta-analytic review. In: Pereis C, Arrindell WA, Eisemann M, editors. Parenting and psychopathology. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazwi F, Nock SL. Religion as a mediating force in the effects of modernization on parent-child relations in Jordan. Middle Eastern Studies. 1989;25:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez V. Quality of family and work roles and its relationship with health indicators in men and women. Sex Roles. 2006;55:787–799. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Bouris A, Acosta N. Parenting practices among Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Social Work. 2007;52:17–30. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas L. Gender equality and social policy: Implications of a study of parental leave in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues. 1990;11:401–423. [Google Scholar]

- Haque A. Relationship between perceived maternal acceptance-rejection and self-esteem among young adults in Nigeria. Journal of African Psychology. 1988;1:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Chinese patterns of socialization: A critical review. In: Bond MH, editor. The psychology of the Chinese people. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Keresteš G. Spol roditelja te dob i spol djeteta kao odrednice roditeljskog ponašanja [Parent gender, and child age and gender as determinants of parental behavior] Suvremena Psihologja. 2001;4:7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002a;64:54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Reliability of measures assessing the pancultural association between perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2002b;33:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Han G, McCubbin MA. Korean American maternal acceptance-rejection, acculturation, and children’s social competence. Family & Community Health. 2007;30:S33–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000264879.88687.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Bornstein MH, Dodge KA, Skinner AT, Putnick DL, Deater-Deckard K. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in the United States. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:199–213. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila M, Garcia F, Gracia E. Perceived paternal and maternal acceptance and children’s outcomes in Colombia. Social Behavior and Personality. 2007;35:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky VG, Dusek JB. Perceptions of child rearing and self-concept development during the early adolescent years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14:373–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02138833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg A. Barn och deras familjer 2005 [Children and their families 2005]. Demografiska rapporter 2006. 2006 Retrieved on October 11, 2011 from http://www.scb.se/Pages/PublishingCalendarViewInfo____259923.aspx?PublObjId=1803.

- MacDonald K. Warmth as a developmental construct: An evolutionary analysis. Child Development. 1992;63:753–773. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson E. Hon, han och hemmet: Genuspsykologiska perspektiv på vardagslivet i nordiska barnfamiljer [She, he, and the home: Gender psychological perspective on everyday life in the Nordic families with children] Stockholm: Natur och kultur; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell B. Translation and cultural adaptation of the survey instruments. In: Martin MO, Kelly DL, editors. Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) technical report, Volume I: Design and development. Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Lauretti A, Talbot J, Pouquette C. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In: McHale J, Grolnick W, editors. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- Medina B. The Filipino family. 2. Diliman, Philippines: University of the Philippines Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nimer E, Samara A. The child, family and society. 2. Amman, Jordan: Darelfekr; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oburu PO. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Kenya. Parenting: Science & Practice. 2011;11:152–162. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oburu PO, Palmerus K. Parenting stress and self reported discipline strategies of Kenyan grandmothers taking care of their orphaned grand children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar P, Ibrahim M, Rohner RP. Relations among perceived spouse acceptance, remembered parental acceptance in childhood, and psychological adjustment among married adults in Kuwait. Cross-Cultural Research. 2008;42:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus DL, Vazire S. The self-report method. In: Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger R, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Perris C, Arrindell WA, Perris H, van der Ende J, Maj M, Benjaminsen S, Ross M, Eisemann M, del Vecchio M. Cross-national study of perceived parental rearing behavior in healthy subjects from Australia, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden: Pattern and level comparisons. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1985;72:278–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb02607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyuchon M, Gray LA. Understanding Thai families: A cultural context for therapists using a structural approach. Contemporary Family Therapy. 1997;19:209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;38:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll-Núñez K, Alvarez C. Perceived intimate partner acceptance, remembered parental acceptance, and psychological adjustment among Colombian and Puerto Rican youths and adults. Cross-Cultural Research. 2008;42:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll-Núñez K, Carrillo S, Castro A. Relación entre hermanos y ajuste psicológico en adolescentes: los efectos de la calidad de la relación padres-hijos [Relationship between siblings and psychological adjustment in adolescents: Effects of the quality of parent-child relationship] Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana. 2009;27:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP. The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist. 2004;59:830–840. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP. Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire (PARQ/Control): Test manual. In: Rohner RP, Khaleque A, editors. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. 4. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 2005. pp. 137–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Britner PA. Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research. 2002;36:16–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Cournoyer DE. Universals in youths’ perceptions of parental acceptance and rejection: Evidence from factor analyses within eight sociocultural groups worldwide. Cross-Cultural Research. 1994;28:371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A, Cournoyer DE. Cross-national perspectives on parental acceptance-rejection theory. In: Peterson GW, Steinmetz SK, Wilson SM, editors. Parent-youth relations: Cultural and cross-cultural perspectives. New York: Haworth Press, Inc; 2003. pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rhucharoenpornpanich O, Chamratrithirong A, Fongkaew W, Rosati MJ, Miller BA, Cupp PK. Parenting and adolescent problem behaviors: A comparative study of sons and daughters in Thailand. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2010;93:293–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Russell G. Warmth in mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1989;7:219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Saebel J. Mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son, and father-daughter: Are they distinct relationships? Developmental Review. 1997;17:111–147. [Google Scholar]

- Senese P, Poderico C, Venuti P. Credenze parentali sulla relazione genitori-figli: Confronto tra diversi gruppi etnici [Parental beliefs about parent-child relationship: A comparison across different ethnic groups] In: Poderico C, Venuti P, Marcone R, editors. Diverse culture bambini diversi? Milano: Unicopli; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Correspondence among informants on parenting: Preschool children, mothers, and observers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:53–68. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek DTL. Adolescents’ perceptions of paternal and maternal parenting styles in a Chinese context. The Journal of Psychology. 1998;132:527–537. doi: 10.1080/00223989809599285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek DTL. Perceived parental control and parent-child relational qualities in early adolescents in Hong Kong: Parent gender, child gender and grade differences. Sex Roles. 2008;58:666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Sorbring E, Gurdal S. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Sweden. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:177–189. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacón A, Caldera Y. Attachment and parental correlates in late adolescent Mexican American women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tapanya S. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in Thailand. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:190–198. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers RL. Parent-offspring conflict. American Zoologist. 1974;14:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Tulananda O, Roopnarine JL. Mothers’ and fathers’ interactions with preschoolers in the home in northern Thailand: Relationships to teachers’ assessments of children’s social skills. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:676–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulananda O, Young DM, Roopnarine JL. Thai and American fathers’ involvement with preschool-aged children. Early Child Development and Care. 1994;97:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. State of the world’s children. New York: UNICEF; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Varan A, Rohner RP, Eryuksel G. Intimate partner acceptance, parental acceptance, and psychological adjustment among Turkish adults in ongoing attachment relationships. Cross-Cultural Research. 2008;42:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Veneziano RA. Perceived paternal and maternal acceptance and rural African American and European American youths’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Veneziano RA. The importance of paternal warmth. Cross-Cultural Research. 2003;37:265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura ER. An overview of child psychology in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Psychology. 1981;14:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti P, Senese VP. Un questionario di autovalutazione degli stili parentali: uno studio su un campione italiano [A self-assessment questionnaire study of parental styles in an Italian sample] Giornale Italiano di Psicologia. 2007;XXXIV(3):667–697. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Chang L. Parenting and child socialization in contemporary China. In: Bond MH, editor. Handbook of Chinese psychology. 2. London: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chang L. Multidimentional parental warmth and control and their relations to pupils’ social development: A comparison between paternal and maternal parenting. Journal of Psychology in Chinese Societies. 2008;9:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting BB, Whiting JW. Children of Six Cultures: A psycho-cultural analysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Winsler A, Madigan AL, Aquilino SA. Correspondence between maternal and paternal parenting styles in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2005;20:1–12. [Google Scholar]