Abstract

Vibrioid- to helical-shaped magnetotactic bacteria phylogenetically related to the genus Magnetospirillum were isolated in axenic cultures from a number of freshwater and brackish environments located in the southwestern United States. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, most of the new isolates represent new Magnetospirillum species or new strains of known Magnetospirillum species, while one isolate appears to represent a new genus basal to Magnetospirillum. Partial sequences of conserved mam genes, genes reported to be involved in the magnetosome and magnetosome chain formation, and form II of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase gene (cbbM) were determined in the new isolates and compared. The cbbM gene was chosen for comparison because it is not involved in magnetosome synthesis; it is highly conserved and is present in all but possibly one of the genomes of the magnetospirilla and the new isolates. Phylogenies based on 16S rRNA, cbbM, and mam gene sequences were reasonably congruent, indicating that the genes involved in magnetotaxis were acquired by a common ancestor of the Magnetospirillum clade. However, in one case, magnetosome genes might have been acquired through horizontal gene transfer. Our results also extend the known diversity of the Magnetospirillum group and show that they are widespread in freshwater environments.

INTRODUCTION

Magnetotactic bacteria (MTB) are a metabolically, morphologically, and phylogenetically heterogeneous group of aquatic prokaryotes that passively align and actively swim along magnetic field lines (3). This behavior, termed magnetotaxis, is due to the presence of intracellular single-magnetic-domain crystals of magnetite (Fe3O4) and/or greigite (Fe3S4) surrounded by a lipid bilayer. These unique structures, called magnetosomes, are generally organized into a chain(s) within the cell and impart a permanent magnetic dipole to the cell, resulting in the cells' magnetotactic behavior (3). MTB are ubiquitous in aquatic habitats typified by the presence of oxygen concentrations and redox gradients in the water column or sediments (3).

Among the MTB, members of the genus Magnetospirillum are the most studied and well understood in terms of the biomineralization of magnetite and the construction of the magnetosome chain. Most of this knowledge is based on the genetic analysis of two species: Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense strain MSR-1 (35) and M. magneticum strain AMB-1 (31). Three Magnetospirillum species are well characterized. The genome of M. magneticum strain AMB-1 has been completed, and while most of the genomes of M. gryphiswaldense strain MSR-1 and M. magnetotacticum strain MS-1 have been sequenced, they have not yet been closed as a chromosome (8, 29). Known magnetotactic Magnetospirillum species are facultatively anaerobic microaerophiles that biomineralize a chain of cuboctahedral crystals of magnetite, although some strains do not produce magnetosomes (e.g., M. bellicus [45]). Morphologically, all known Magnetospirillum species are helical and are bipolarly flagellated. Metabolically, they all appear to have only a strictly respiratory form of metabolism. They all grow chemoorganoheterotrophically using organic acids as electron and carbon sources (4), while some species have been shown to grow chemolithoautotrophically using reduced sulfur compounds as an electron source and the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle for autotrophy (14, 15). Several other Magnetospirillum strains have not yet been shown to grow autotrophically but show a strong potential for this metabolic feature, as they possess a form II ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) gene (cbbM) (6).

Three possible evolutionary hypotheses have been described to explain the phylogenetic diversity of MTB. The first states that the trait of magnetotaxis is monophyletic and that all MTB originated from a single common ancestor of the MTB (1, 23). In the second hypothesis, the magnetotactic trait is polyphyletic, that is, evolved independently several times (e.g., based on iron oxide or sulfide production [11]) and was then lost in several lineages, resulting in bacteria that lost their ability to produce magnetosomes while remaining phylogenetically closely related to MTB. The third scenario involves multiple events of horizontal gene transfer while the original magnetosome genes could still have originated from a single ancestor (22, 36, 46).

The genes putatively responsible for the biomineralization of magnetite were originally discovered in Magnetospirillum species and are referred to as the mam and/or mms genes (17, 18, 21, 25). Many of these genes encode proteins in the cytoplasmic membrane-derived magnetosome membrane, some of which are not present anywhere else in the cell (26, 39, 44). Most, if not all, of these genes are located in the genome as clusters within a genomic magnetosome island (MAI) in Magnetospirillum species and other MTB that is thought to be distributed between nonmagnetotactic species via horizontal gene transfer (22).

Although the precise roles of many of the magnetosome (mam) genes remain unknown, mamAB, mamGFDC, mamXY, and mms6 clusters have been implicated in magnetite biomineralization (29, 33). Some of the genes within these clusters are responsible for controlling the size and morphology of magnetite crystals in MTB as well as the magnetosome chain organization (21, 25). Comparisons between the MAIs of different cultured magnetite-producing MTB show that the gene contents and organizations differ among them and are thought to be responsible for differences in magnetosome crystal morphology, size, and organization (21). Magnetosome genes are also conserved in the magnetotactic Deltaproteobacteria, including Desulfovibrio magneticus (34), “Candidatus Magnetoglobus multicellularis” (1), and “Candidatus Desulfamplus magnetomortis” (27), and in magnetotactic Nitrospirae, including “Candidatus Magnetobacterium bavaricum” (24). Results from some of those studies appear to contradict the polyphyletic model described previously by DeLong et al. (11) and suggest a model in which the ability to produce magnetosomes and the possession of the mam genes were monophyletic and derived from a common ancestor (1, 23). However, the number of magnetosome gene sequences available from cultured and uncultured MTB is not sufficient to build robust phylogenies to be used in elucidating the evolution of magnetotaxis and how the magnetotactic trait was acquired by different clades of MTB.

In this study, degenerate primers were designed for the amplification of 8 mam genes (mamA, mamB, mamK, mamM, mamO, mamP, mamQ, and mamT) of Magnetospirillum species using PCR on 13 newly isolated, mainly freshwater MTB phylogenetically related to Magnetospirillum species. These 8 mam genes were chosen because they show high levels of similarity in all MTB characterized thus far and are thought to play an important role in magnetosome formation (39). We sequenced these gene fragments and compared phylogenies based on these mam gene sequences with those based on 16S rRNA and on ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase form II (cbbM) gene sequences to investigate whether phylogeny based on mam genes could give insight into whether the origin of magnetotaxis in the magnetospirilla is monophyletic. Indeed, if the phylogenies based on mam genes are congruent with the phylogenies based on genes that are known to have evolved monophyletically, such as the 16S rRNA gene, it seems likely that the genes diverged similarly, and thus, it also seems likely that magnetotaxis evolved in the same way. The cbbM gene was chosen for comparison because it is not involved in magnetosome synthesis, is highly conserved, and is present in all but possibly one of the genomes of the newly isolated MTB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and sample collection.

Water and sediment samples were taken from various aquatic ecosystems: three sites, Boulder Beach, Saddle Island, and Callville Bay, in Lake Mead, NV; a small pond near Zion National Park in Utah; a spring at the Corn Creek Field Station in the Desert National Wildlife Refuge in Nevada; a pond near Mono Lake, CA; Kolob Reservoir, UT; the Alamo River near the Salton Sea in California, and Lake Ely, PA (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Samples were collected from the shore. One- or two-liter plastic or glass bottles were filled to about 20 to 30% of their volume with sediment, and the reminder of the bottles were filled to their capacity with water that overlaid the sediment. Air bubbles were excluded. Once in the laboratory, samples were stored under dim light at room temperature (∼25°C).

Isolation of MTB.

Cells of MTB were magnetically concentrated by placing the south pole of a magnetic stirring bar next to sample bottles at the sediment-water interface for ∼30 min and then further purified by using the capillary magnetic racetrack technique (48). These cells were used as inocula in a modified semisolid oxygen concentration gradient enrichment medium similar to that described previously by Bazylinski et al. (6). Five milliliters of modified Wolfe's mineral elixir (5, 49), 0.2 ml 1% aqueous resazurin, 0.3 g NH4Cl, 0.1 g MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.68 g sodium acetate were added to a liter of water, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0. A total of 2.0 g of Bacto agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) was then added, after which the medium was autoclaved. After autoclaving, the following ingredients were added as sterile stock solutions (per liter): 0.5 ml of vitamin solution (13), 2.8 ml of 0.5 M KHPO4 buffer (pH 7.0), 5 ml of neutralized 100 mM sodium sulfide (Na2S · 9H2O), 3 ml of 10 mM FeSO4 · 7H2O (in 0.02 N HCl), 1.8 ml of 0.8 M sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) solution, and 10 ml of a filter-sterilized, freshly made, 4% neutralized cysteine · HCl · 2H2O solution. The medium was dispensed into sterile, screw-cap glass tubes at ∼80% of their volume. The medium was incubated at room temperature for several hours to solidify and to allow the O2 concentration [O2] gradient to form, as evidenced by the presence of a pink (oxidized) zone near the surface and a colorless (reduced) zone in the lower portion of the tubes.

Axenic cultures were obtained by first plating the cells onto solid ACA medium, as described previously by Schultheiss and Schüler (41), except that the iron source added after autoclaving was 3 ml of 10 mM FeSO4 · 7H2O per liter of growth medium. After ∼10 days of growth on solid medium, a single, dark-colored colony was transferred into semisolid [O2] gradient medium, from which cells were diluted to extinction in the same medium. Light microscopy was used to assess whether the cultures were magnetotactic through the various transfers. Finally, to determine the 16S rRNA gene sequence of each strain (see details below), three clones from each culture were used. In all cases, for each individual culture, the sequences of the three clones were identical.

Light and electron microscopy.

The presence and behavior of the newly isolated MTB were determined by using a Zeiss AxioImager M1 light microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY) equipped with phase-contrast, fluorescence, and differential interference contrast capabilities. The hanging-drop technique (38) was used routinely for the examination of samples and for the quantification of MTB. The local magnetic field used to determine magnetotaxis was a large stirring bar magnet placed onto the microscope stage.

Cell morphology and the presence and morphology of magnetosomes were determined by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a Tecnai (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) model G2 F30 Super-Twin or a G2 Biotwin transmission electron microscope. Cells were deposited onto carbon-coated grids and dried in air; for the observation of flagella, cells were negatively stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 min.

Determination of 16S rRNA, cbbM, and mam gene sequences.

Primers used for the amplification of genes are shown in Table 1. Degenerate primers were designed by using AmplifX software, version 1.44 (Nicolas Jullien [http://ifrjr.nord.univ-mrs.fr/AmplifX-Home-page]), based on the sequence alignment of previously sequenced mam genes of strains AMB-1, MS-1, and MSR-1, also taking into consideration the sequences of “Candidatus Magnetovibrio blakemorei” strain MV-1 (D. A. Bazylinski et al., submitted for publication) and Magnetococcus marinus strain MC-1 (7, 37). The position of the forward primers was selected to be as close as possible to the start codon and the position of the reverse primers was selected to be as close as possible to the stop codon in order to obtain a sequence that was nearly full length. Whole-cell PCR was performed by using fresh cell lysates from pure cultures obtained by boiling cell suspensions for 5 min with JumpStart Red Taq ReadyMix PCR mix (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, St. Louis, MO) and/or GoTaq Green master mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) and the same basic protocol consisting of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, annealing for 30 s (the temperature varied depending on the GC% contents of the primer sets), and extension at 72°C (the time varied depending on the sequence length to be amplified), followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min; the reaction mixtures were then held at 4°C. Chromosomal DNA was occasionally used in PCRs where it was difficult to obtain PCR products by using whole-cell PCR. In this case, DNA was extracted from cell pellets by using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCR products of the 16S rRNA gene were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), and three clones for each isolate were sequenced to ensure that the cultures were pure. PCR products of the mam and cbbM genes were directly purified and sequenced (Functional Biosciences, Inc., Madison, WI).

Table 1.

Primer sets used for PCR amplifications of specific mam and cbbM genes

| Primer set | Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| 16S rRNA | AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG | TACGGHTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 25a |

| mamA | ATGTCTAGCAAGCCGTCG | GATGCACCTTGCCTTCATTG | |

| mamB | ATGAAGTTCGAAAATTGCAGRGA | TACCGCCTCGGCCACCAT | |

| mamK | TCGACCTTGGGACTTCCCATAC | CCAAGCTGACYCCAATACTG | |

| mamM | ATGAGGAAGAGCGGTTGC | TTATCCACCTTSGACARCATGAC | |

| mamO | ATGATTGAARTYGGCGAGACCATG | TCACACCGWKGTCAGCATCTTGA | |

| Middle | GATCACCCATCTGYTGCGBT | CGGATCAGATACATGCCATAGC | |

| mamP | GAATAGCAARSTSGYSCTKCTG | TSACGTGGCARGCTTCGCA | |

| mamQ | CTRCAACGGGTSAAGCAGT | TCCTGCGMATGGKTGAGAG | |

| mamT | TCGGRCTGGGACTCTATTGGGA | CTTKTCCACMGGCACCTTGACC | |

| mamA, mamO, and mamP (strains UT-2 and UT-4 only) | GGCGGTTTCCTTTCTGCACGG | TCGCGATAGAAGGACAAACGG | |

| RuII-1 | GGHAACAACCARGGYATGGGYGA | CGHAGIGCGTTCATGCCRCC | 42 |

| RuII-2 | GGIACVATCATCAARCCVAA | TGRCCIGCICGRTGRTARTGCA | 42 |

Phylogenetic tree construction.

The alignment of 16S rRNA, mam, or cbbM genes was performed by using the CLUSTAL W multiple-alignment accessory application in the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (20). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using MEGA, version 5 (43), applying the maximum likelihood algorithm (19). Bootstrap values were calculated with 100 replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Partial sequences of the 16S rRNA, cbbM, mamA, mamB, mamK, mamM, mamO, mamP, mamQ, and mamT genes determined in this study were assigned the GenBank accession numbers listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of the partial 16S rRNA, cbbM, mamA, mamB, mamK, mamM, mamO, mamP, mamQ, and mamT genes from the new MTB strains described in this study

ND, not determined.

RESULTS

Description of sampling sites and samples.

All water and sediment samples collected from numerous aquatic environments located in the southwestern United States (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) contained MTB of various morphologies. These included cocci, large ovoid cells, vibrios, and rods as well as spirilla morphologically similar to Magnetospirillum species. All sites were freshwater sites having salinities of <1 ppt, except the Alamo River near the Salton Sea, which was brackish, with a salinity of ∼4 ppt. In most of the sites, the concentration of magnetic spirilla was relatively low compared to that of other magnetotactic morphotypes, and in some cases, none were observed prior to their cultivation.

Isolation and axenic cultures of MTB.

Magnetically purified cells from the different sample sites were used for inoculation into semisolid, O2 concentration ([O2]) gradient growth medium. After approximately 1 week of incubation at 25°C, most of the tubes inoculated with MTB showed evidence of growth. Microaerophilic bands of cells were present in these tubes at the pink-colorless, oxic-anoxic interface (OAI). Microscopic examination of the cells in these cultures showed that the cells were magnetotactic and vibrioid to helical in morphology. MTB from different tubes were inoculated onto solid agar plates of modified ACA medium to obtain single colonies. Five strains were isolated from various locations in Lake Mead, including three strains from Boulder Beach, designated LM-1, LM-4, and LM-5; one strain from Saddle Island, named strain LM-2; and one strain from Callville Bay, named CB-1. In addition, three strains were isolated from a small pond in Utah and designated UT-1, UT-2, and UT-4. Single strains were isolated from the Kolob Reservoir in Utah (strain KR-1), from Corn Creek in Nevada (strain CC-2), from Lake Ely in Pennsylvania (strain LEMS), from a pond near Mono Lake in California (strain NML-1), and from the Alamo River near the Salton Sea in California (strain SS-4) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). While magnetospirilla related to the genus Magnetospirillum were isolated from all freshwater sources studied, we were unable to isolate them from any saline environment examined.

Morphology, magnetotaxis, and magnetosomes of the newly isolated MTB.

Most of the newly isolated MTB are similar in morphology to Magnetospirillum species (Fig. 1). When grown in semisolid [O2] gradient medium, cells were mostly long spirilla (3 to 5 μm in length and 0.4 to 0.6 μm in width) that were bipolarly flagellated. Cells of strains UT-2 and UT-4 were slightly smaller than the others (Fig. 2A and B). One strain, LM-1, was considered a vibrio because of the presence of a single polar flagellum (Fig. 2C).

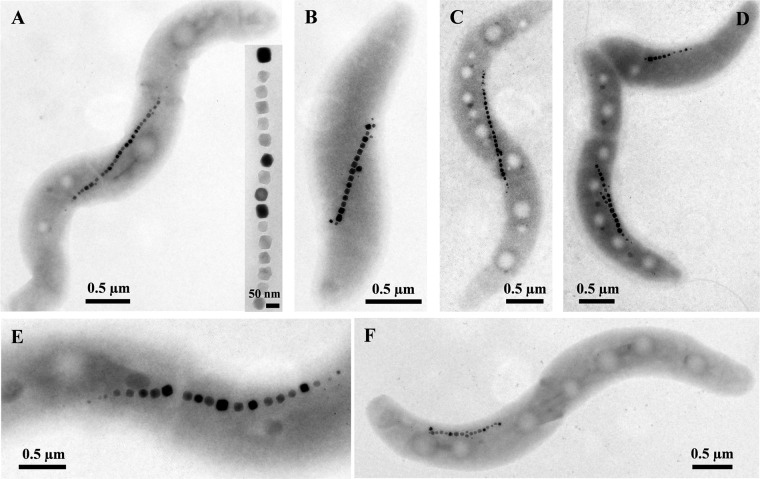

Fig 1.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of cells of newly isolated magnetotactic bacteria (MTB) morphologically similar to Magnetospirillum species. (A) Strain CB-1. The inset shows a magnetosome chain at a higher magnification. (B) Strain SS-4. (C) Strain LM-4. (D) Strain LM-5 negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. (E) Strain KR-1. (F) Strain NML-1. Note that all strains biomineralize cuboctahedral crystals, which consist of magnetite. When negatively stained, two polar flagella were visible.

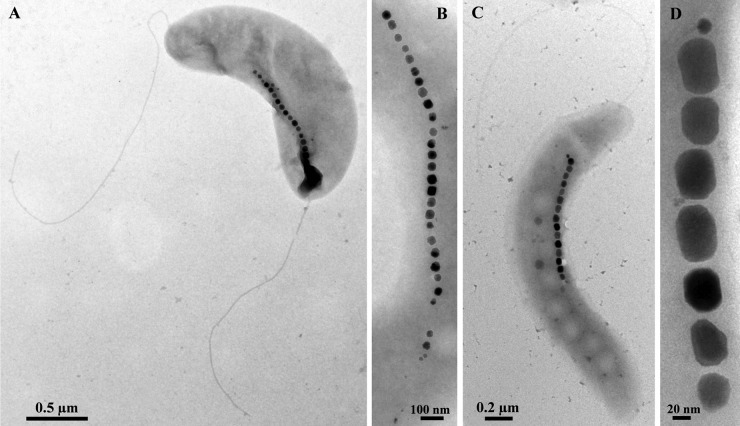

Fig 2.

TEM images of cells of the newly isolated MTB that are slightly different in morphology from Magnetospirillum species. (A) A cell of strain UT-2 negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Note the more vibrioid morphology. (B) Magnetosome chain of strain UT-4 showing cuboctahedral crystals. (C) Cell of strain LM-1 negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Note the presence of a single polar flagellum. (D) High-magnification TEM image of a chain of elongated prismatic crystals of magnetite in a cell of strain LM-1.

Using the hanging-drop technique, all the new isolates displayed north-seeking, polar magnetotactic behavior (i.e., swam persistently toward the south pole of a bar magnet). With the exception of strain LM-1, all isolates synthesized cuboctahedral crystals (Fig. 1 and 2A and B) identical to those found in other known Magnetospirillum species. Strain LM-1 synthesizes elongated prismatic crystals (Fig. 2C and D) resembling crystals of “Candidatus Magnetovibrio blakemorei” strain MV-1 (32; Bazylinski et al., submitted). A shape factor (defined as width/length) distribution analysis was performed on the magnetosome magnetite crystals of strain LM-1, which had an average shape factor of 0.78 ± 0.10 (n = 81) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The distribution and shape factor averages of LM-1 magnetite crystals are typical of elongated prismatic magnetosome magnetite crystals from other MTB (12).

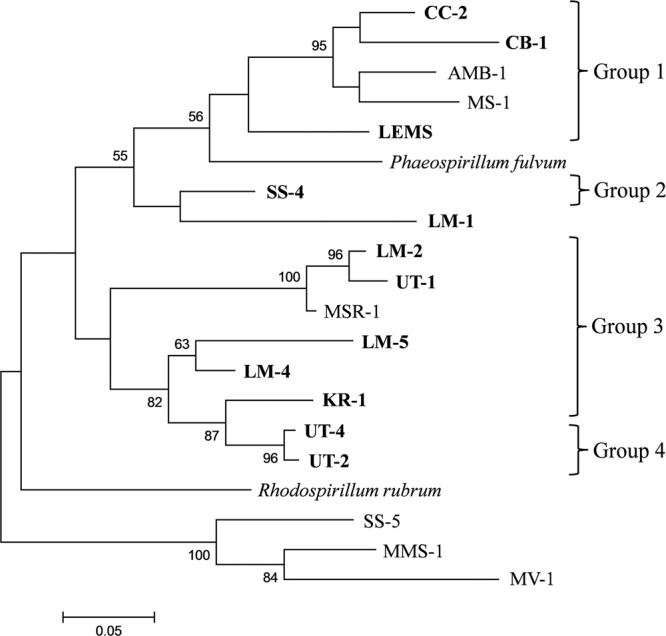

Phylogenetic analysis of the new isolates based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

16S rRNA gene sequences of the newly isolated MTB indicate that they phylogenetically belong to the family Rhodospirillaceae of the class Alphaproteobacteria (Fig. 3) and that they are closely related to known Magnetospirillum and Phaeospirillum species. The new isolates form 4 distinct groups within these two genera (Fig. 3). The first group contains the three known MTB, AMB-1, MS-1, MGT-1, and the two new isolates CB-1 and CC-2. The second group is composed of LEMS, NML-1, and SS-4. The third group comprises M. gryphiswaldense strain MSR-1, M. bellicus, M. aberrantis, and the new isolates KR-1, LM-5, UT-1, LM-2, and LM-4. Finally, the fourth group, which appears basal to all the other Magnetospirillum species, contains strains UT-2 and UT-4.

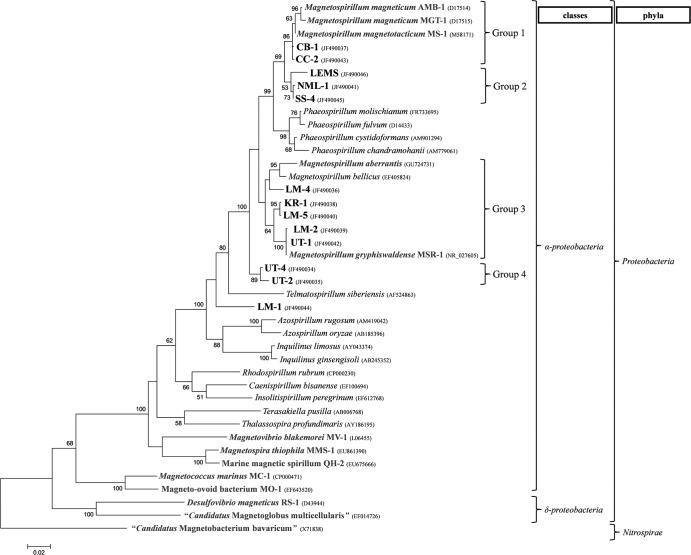

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the phylogenetic positions of the newly isolated MTB (boldface type) and other MTB (gray). “Candidatus Magnetobacterium bavaricum” (phylum Nitrospirae) was used to root the tree. Bootstrap values (higher than 50) at nodes are percentages of 100 replicates. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. The bar represents 2% sequence divergence.

Based on current criteria (10), LM-2 and UT-1 represent new strains of M. gryphiswaldense, CC-2 and CB-1 represent new strains of M. magneticum, and the remaining isolates, except strain LM-1, represent novel species of the genus Magnetospirillum. Based on its 16S rRNA sequence (Table 3), LM-1 can be considered a new genus, with its closest relative in culture being M. magneticum strain AMB-1, with a 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of 91.0%.

Table 3.

16S rRNA sequence identity between the newly isolated MTB and the known magnetotactic Magnetospirillum speciesa

| Strain | % identity with strain: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MSR-1 | AMB-1 | MS-1 | |

| LM-1 | 90.35 | 91.02 | 90.01 |

| LM-2 | 99.79 | 96.03 | 94.85 |

| LM-4 | 96.51 | 95.75 | 94.59 |

| LM-5 | 96.93 | 95.48 | 94.52 |

| CB-1 | 95.61 | 98.95 | 98.02 |

| UT-1 | 99.72 | 96.09 | 94.93 |

| UT-2 | 94.94 | 94.46 | 93.49 |

| UT-4 | 95.34 | 95.13 | 94.1 |

| KR-1 | 97.28 | 95.68 | 94.73 |

| CC-2 | 96.03 | 99.37 | 98.16 |

| LEMS | 96.15 | 96.58 | 95.63 |

| NML-1 | 96.44 | 97.34 | 96.39 |

| SS-4 | 96.65 | 97.62 | 96.68 |

| MSR-1 | 95.97 | 94.86 | |

| AMB-1 | 95.97 | 97.95 | |

| MS-1 | 94.86 | 97.95 | |

Phylogenetic analysis of mam gene sequences.

Using degenerate primers and PCR (Table 3), we amplified and determined partial sequences of 8 mam genes in the new isolates (Table 4). For UT-2 and UT-4, mamA, mamO, and mamP were sequenced by using a forward primer designed from the start of mamO and a reverse primer designed from the end of mamA of the alignment of known Magnetospirillum mam gene sequences; the sequencing of these three genes using this technique indicated that mamO, mamP, and mamA are also in synteny in the genomes of UT-2 and UT-4.

Table 4.

Maximum identities of mam gene sequences between MTB isolated in this study and known magnetotactic Magnetospirillum species

| Strain | % maximum identity (% length of gene recovered)a |

Strain sharing maximum identityb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mamA | mamB | mamK | mamM | mamO | mamP | mamQ | mamT | ||

| LM-1 | 68.51 (99.5) | 74.97 (100) | ND | ND | ND | 75.39 (90.9) | 66.11 (94.1) | ND | MSR-1 |

| LM-2 | 100 (80.6) | 99.87 (86.8) | 100 (83.2) | 100 (86.9) | 99.94 (92.4) | 99.87 (94.6) | 100 (87.7) | 100 (79.8) | MSR-1 |

| LM-4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 73.9 (82.7) | AMB-1 |

| LM-5 | 99.62 (78.8) | 98.94 (74.0) | 99.54 (83.0) | 99.57 (72.2) | 99.10 (92.6) | 98.98 (95.2) | 99.15 (86.2) | 99.51 (77.9) | AMB-1 |

| CB-1 | 100 (79.7) | 99.49 (87.3) | 99.44 (85.2) | 99.72 (74.9) | 99.27 (92.6) | 99.48 (92.9) | 99.15 (86.0) | 99.29 (80.2) | AMB-1 |

| UT-1 | 100 (80.1) | 99.87 (86.2) | 99.89 (85.5) | 100 (87.8) | 99.83 (92.1) | 100 (94.5) | 100 (86.2) | 100 (79.8) | MSR-1 |

| UT-2 | 81.82 (78.7) | ND | ND | ND | 78.08 (92.1) | 81.6 (97.8) | ND | ND | AMB-1 |

| UT-4 | 81.21 (79.1) | ND | ND | ND | 78.18 (92.2) | 81.4 (97.8) | ND | ND | AMB-1 |

| KR-1 | 96.95 (80.6) | 96.64 (86.5) | 97.62 (80.5) | 95.87 (88.4) | 98.75 (92.9) | 96.10 (94.7) | 97.32 (86.7) | 98.36 (81.9) | MSR-1 |

| CC-2 | 100 (79.1) | 99.74 (87.3) | 99.54 (83.0) | 99.66 (91.5) | 99.21 (92.7) | 99.49 (94.7) | 99.00 (85.6) | 99.72 (67.8) | AMB-1 |

| LEMS | 90.48 (86.1) | 91.59 (85.1) | 93.36 (83.7) | 93.76 (92.4) | 95.46 (92.8) | 89.48 (94.8) | 92.79 (88.0) | 92.06 (81.9) | MSR-1 |

| NML-1 | 92.03 (82.9) | 94.45 (70.6) | 91.30 (84.3) | 96.63 (80.6) | 91.83 (91.7) | 89.11 (65.5) | 91.45 (88.6) | 87.57 (72.6) | AMB-1 |

| SS-4 | 92.27 (81.5) | 95.43 (85.9) | 91.10 (76.1) | 96.14 (92.0) | 92.16 (93.1) | 87.52 (93.5) | 90.77 (86.0) | 88.33 (80.0) | AMB-1 |

Values in parentheses represent the percentages of the lengths of the genes recovered with degenerate primers.

Indicates the species with the maximum identity of mam gene sequences.

For strain LM-1, only partial sequences of mamA, mamB, mamP, and mamQ were amplified and sequenced. For LM-4, only a partial sequence of mamT was obtained. Based on phylogenetic analysis, the evolution of this gene is not congruent with the phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence. For the acquisition of this gene in LM-4, it may be more likely due to a horizontal gene transfer event. Considering the difficulty in obtaining other mam genes from LM-4 with degenerate primers designed from other Magnetospirillum species, it seems that the other mam genes of this strain have a high level of divergence from those of the other Magnetospirillum species.

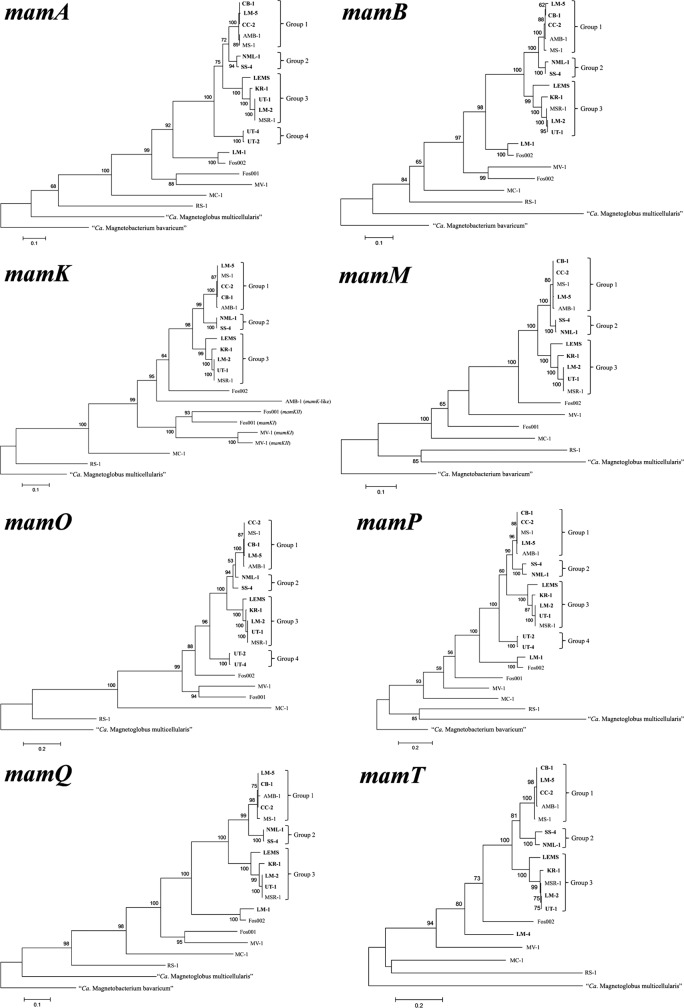

Partial sequences of the 8 mam genes were determined for all the other newly isolated strains, LM-2, LM-5, CB-1, UT-1, KR-1, CC-2, NML-1, SS-4, and LEMS. All phylogenetic trees based on mam gene sequences are congruent with the phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence (Fig. 4), with the exception of strains LM-4, LM-5, and LEMS, which are positioned differently in the tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and those based on mam genes. The separation of the four different groups in the 16S rRNA phylogeny is conserved in the phylogenies based on mam genes, except that in the phylogenies based on mam genes, LM-5 belongs to group 1 and strain LEMS appears to be related to group 3 and not to group 2. Phylogenies based on mam genes confirm the basal position of UT-2 and UT-4 in the Magnetospirillum group. The phylogenetic position of strain LM-1 remains basal to the entire Magnetospirillum group.

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic trees based on mamA, mamB, mamK, mamM, mamO, mamP, mamQ, and mamT gene sequences (see Table 4 for lengths of the sequences) from the newly isolated MTB and other characterized MTB. Bootstrap values (>50) at nodes are percentages of 100 replicates. Magnetosome gene sequences from “Candidatus Magnetobacterium bavaricum” were used as an outgroup when its appropriate mam gene sequence was available; if not available, those from “Candidatus Magnetoglobus multicellularis” were used.

Phylogenies based on amino acid sequences of the corresponding Mam proteins were also constructed. The phylogenetic positions of the new MTB strains in the Mam protein trees were similar to those based on mam gene nucleotide sequences (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Phylogenetic analysis of the cbbM gene sequences.

The phylogeny and relatedness of the new MTB strains based on cbbM gene sequences are reasonably consistent with those based on 16S rRNA genes (Fig. 5; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Strains UT-2 and UT-4 do not form a separate branch; they form a clade with KR-1, which belongs to group 3. Strains LM-4 and LM-5 belong to group 3, as they do in the phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. A phylogenic tree based on amino acid sequences of the CbbM protein was also constructed and was consistent with that based on cbbM gene sequences (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). However, some differences were observed between these phylogenies and can be explained by bootstraps values that are <50%.

Fig 5.

Phylogenetic tree based on cbbM gene sequences from the newly isolated MTB. Bootstrap values (>50) at nodes represent percentages of 100 replicates. Strain SS-5 (28), Magnetospira thiophila strain MMS-1 (47), and “Candidatus Magnetovibrio blakemorei” strain MV-1 (6) were used as outgroups.

We were unable to amplify the cbbM gene of NML-1. The nested PCR program, using the primer sets RuII-1 and RuII-2 (Table 1), has been used for the amplification of the partial cbbM gene sequences of SS-4 and LEMS but was unsuccessful for NML-1. Spiridonova et al. (42) previously used this program to amplify the cbbM gene of Phaeospirillum fulvum, a close relative of LEMS, SS-4, and NML-1, which have 16S rRNA gene sequence identities of 95.69, 96.59, and 96.73% with P. fulvum, respectively. It is also possible that the cbbM gene is absent in the genome of strain NML-1. In the phylogeny based on cbbM gene sequences, the genus Phaeospirillum (only one cbbM sequence is available in the GenBank database, that of P. fulvum) is also included in the group formed by all the Magnetospirillum species.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 13 new vibrioid-to-helical MTB strains were isolated in axenic cultures. Among the new isolates, 10 are clearly members of the genus Magnetospirillum. Strains UT-2 and UT-4 have a maximum 16S rRNA sequence identity of ∼95% with some characterized Magnetospirillum strains. Based on current criteria, this borderline value (10) does not convincingly demonstrate that these strains are actually species of the genus Magnetospirillum. Therefore, more information (e.g., results from DNA/DNA hybridization experiments) is needed to conclude whether they belong to the genus Magnetospirillum or represent another closely related genus basal to the group formed by the genera Magnetospirillum and Phaeospirillum.

Strain LM-1 unequivocally represents a new genus basal to the branch formed by the genera Magnetospirillum and Phaeospirillum. Interestingly, this strain not only differs from Magnetospirillum species phylogenetically but also differs morphologically in having only a single polar flagellum and elongated prismatic crystals of magnetite. The mam gene sequences from LM-1 exhibit high levels of identity (between 90.38 and 94.07%) to those present on Fos002, a fosmid carrying a metagenomic mam gene cluster from an unidentified, uncultivated, magnetotactic bacterium magnetically collected from the environment (23). Unfortunately, Fos002 does not contain a copy of a 16S rRNA gene, and thus, it is not known whether organisms similar to strain LM-1 are present in the habitat from where Fos002 was recovered.

When the data are taken in their entirety, the magnetospirilla are a large group that appears to phylogenetically span a number of genera. Current data suggest that species of Phaeospirillum should be reclassified and included in the genus Magnetospirillum. Indeed, the genus Phaeospirillum contains spiral-shaped, phototrophic, purple nonsulfur bacterial species (e.g., see reference 2), a physiological trait that is not shared with species of the genus Magnetospirillum, although the presence of intracellular membranes is common to both Phaeospirillum (16) and magnetosome-forming Magnetospirillum species. However, considering the phylogenetic relationship between Phaeospirillum and Magnetospirillum, it would be necessary to modify the classification of the branch grouping Magnetospirillum and Phaeospirillum species by including the Phaeospirillum species in the genus Magnetospirillum or by dividing members of the genus Magnetospirillum into several different genera. Schüler et al. (40) also noticed that, depending on the analysis, Phaeospirillum fulvum and P. molischianum (the only Phaeospirillum species available at the time of the study) did not form a separate branch and were phylogenetically positioned among Magnetospirillum strains.

The relatively small number of MTB in pure culture is a major limitation in studying the evolution of genes involved in magnetotaxis and the transfer of the MAI. However, in this study, we showed that the targeted isolation of freshwater magnetospirilla provided important insights into the evolution of mam genes in this group. Indeed, the isolation of 13 new MTB from freshwater environments and the subsequent sequencing of 8 of their mam genes indicated a vertical inheritance (evolving from a common ancestor of the magnetospirilla) of these mam genes, and perhaps the entire mam gene cluster or island, for at least 10 species. For strain LEMS, the situation appears to be more complicated, and differences between the phylogenies based on the 16S rRNA gene, cbbM, and the 8 mam gene sequences can be explained by the position of LEMS basal to group 2 in the phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence. Thus, it is difficult to conclude if the mam genes of LEMS evolved from those acquired by a common ancestor, as apparently occurred in other Magnetospirillum strains, or if these genes evolved polyphyletically and were acquired by LEMS by horizontal gene transfer. To determine how LEMS acquired the ability to form magnetosomes, it would be necessary to isolate other strains closely related to it that are phylogenetically positioned between groups 1 and 2 and to have the sequences of their mam genes. The closest phylogenetic relative of strain LM-5 in culture, based on the 8 mam gene sequences, is M. magneticum strain AMB-1 (gene sequence identity of between 98.98 and 99.62%), while the phylogeny based on 16S rRNA gene sequences positions LM-5 more closely with M. gryphiswaldense strain MSR-1 (16S rRNA gene sequence identity of 96.93%). Interestingly, the sequence identity shared by the 16S rRNA genes of LM-5 and MSR-1 is lower than the sequence identities shared by the 8 individual mam genes of LM-5 and AMB-1, suggesting that for strain LM-5, the mam genes under study, and perhaps the entire mam gene cluster or island, were acquired by horizontal gene transfer from another Magnetospirillum species closely related to M. magneticum. The failure to amplify mam genes with the degenerate primers for UT-2, UT-4, and LM-1 could be due to a mismatch(es) in the sequences or to significant sequence divergence, with the latter possibly being indicative of the phylogenetic distance between these strains and the Magnetospirillum strains that were used to design the degenerated mam genes primers. These degenerate primers were also tested on Magnetococcus marinus strain MC-1 (7, 37) and “Candidatus Magnetovibrio blakemorei” strain MV-1 (Bazylinski et al., submitted) of the class Alphaproteobacteria and on strains BW-2 and SS-5 of the class Gammaproteobacteria (28), which are magnetotactic species phylogenetically distant from Magnetospirillum, and failed to amplify any mam gene. An important question raised here involves how much divergence of these genes must occur before our PCR primers become ineffective in amplifying these genes. It seems likely that strain LM-4 acquired the ability to form magnetosomes through horizontal gene transfer because we were successful in the amplification of only mamT, which presents a low level of similarity with the mam genes of other Magnetospirillum species.

Phylogenetic trees based on amino acid sequences of Mam proteins were also constructed for comparison. The phylogenetic positions of the new MTB strains in these trees were similar to those based on gene nucleotide sequences, indicating that the mam genes are well conserved at the nucleotide level and can be used to compare phylogenetically closely related MTB species.

Because most, if not all, of the magnetospirilla possess a cbbM gene, and because this gene is relatively highly conserved (42) and not involved in magnetosome synthesis, cbbM was used for comparisons of phylogenetic analyses. The phylogeny and relatedness of the Magnetospirillum strains based on cbbM sequences were reasonably consistent with those based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. These results suggest that the cbbM gene evolved similarly to the 16S rRNA gene in the magnetospirilla and that it was likely acquired by a common ancestor (monophyletic) and not by horizontal gene transfer. A phylogenic tree based on amino acid sequences of the CbbM protein was constructed and was similar to that based on cbbM gene sequences.

This study raises an important question: were the common ancestors of Phaeospirillum and nonmagnetotactic Magnetospirillum species ever magnetotactic? Three scenarios are possible. First, nonmagnetotactic Magnetospirillum species (e.g., M. bellicus [45]) may have been magnetotactic in their natural environment when sampled but lost the ability to produce magnetosomes during their isolation in culture due to the use of nonappropriate cultivation techniques for magnetosome formation. This is certainly plausible, as many cultivated MTB have been reported to lose this trait upon repeated subcultivation in the absence of selective pressure (9, 31, 36, 39), from the loss or rearrangement of the MAI. It is also possible that some of these species contain the necessary set of mam genes and need to be cultivated under the appropriate conditions (e.g., under microaerobic conditions in the presence of an appropriate iron source) and analyzed by using the appropriate microscopic techniques to express magnetotaxis (e.g., the hanging-drop technique). Another possibility is that these strains were magnetotactic, having inherited this trait from a common ancestor along with other Magnetospirillum species, but lost this trait due to environmental and/or physiological pressures, implicating multiple events leading to the loss of the MAI. The last possibility is that the magnetotactic trait (magnetosome biomineralization) was inherited by all magnetotactic species of this group by horizontal gene transfer and that the nonmagnetotactic strains never acquired the genes necessary for magnetosome formation. However, the last scenario contradicts the monophyletic evolution of the magnetosome gene model obtained in this study.

The fact that strains LM-1, LM-4, and LM-5 were isolated from the same sample collected from Lake Mead and that LM-2 and CB-1 were isolated from other samples collected at the same lake indicates that there is a large genetic diversity of vibrioid-to-helical MTB in this ecosystem. Such diversity would not be resolved by light or electron microscopy observations because of the almost identical morphologies and magnetotactic behaviors of these MTB. Schüler et al. (40) also isolated several different Magnetospirillum strains from a single environment (McFarland Pond, located in Ames, IA). Among the McFarland pond strains, MSM-3 and MSM-4 are phylogenetically closely related to strains LM-5 and KR-1 (>99.5% identities of the 16S rRNA gene sequences) and belong to the same clade in the Magnetospirillum group (data not shown), while MSM-6 appears to be a new strain of M. magneticum closely related to strain CC-2 of this study (>99.9% identity of the 16S rRNA gene sequences). This indicates that the biodiversity of Magnetospirillum-like MTB and, therefore, MTB in general is much greater than what has been estimated thus far. In addition, the isolation of new species is important to determine the diversity of the MTB, to understand how mam genes originated and/or are transferred between different MTB, and to know whether magnetotaxis is mono- or polyphyletic in different phylogenetic branches containing MTB.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grant EAR-0920718. C.T.L. was the recipient of an award from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) (SPF20101220993). N.V. was the recipient of an award from the NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program, a Broad View of Environmental Microbiology, at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas (award NSF-0649267).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abreu F, et al. 2011. Common ancestry of iron oxide- and iron-sulfide-based biomineralization in magnetotactic bacteria. ISME J. 5:1634–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anil Kumar P, et al. 2009. Phaeospirillum chandramohanii sp. nov., a phototrophic alphaproteobacterium with carotenoid glycosides. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:2089–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bazylinski DA, Frankel RB. 2004. Magnetosome formation in prokaryotes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bazylinski DA, Williams TJ. 2007. Ecophysiology of magnetotactic bacteria, p 37–75 In Schüler D. (ed), Microbiology monographs: magnetoreception and magnetosomes in bacteria. Springer Press, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bazylinski DA, Dean AJ, Schüler D, Phillips EJ, Lovley DR. 2000. N2-dependent growth and nitrogenase activity in the metal-metabolizing bacteria, Geobacter and Magnetospirillum species. Environ. Microbiol. 2:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bazylinski DA, et al. 2004. Chemolithoautotrophy in the marine, magnetotactic bacterial strains MV-1 and MV-2. Arch. Microbiol. 182:373–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bazylinski DA, et al. 2012. May 11 Magnetococcus marinus gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine, magnetotactic bacterium that represents a novel lineage (Magnetococcaceae fam. nov.; Magnetococcales ord. nov.) at the base of the Alphaproteobacteria. [Epub ahead of print.] Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.038927-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertani LE, Weko J, Phillips KV, Gray RF, Kirschvink JL. 2001. Physical and genetic characterization of the genome of Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum, strain MS-1. Gene 264:257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blakemore RP, Maratea D, Wolfe RS. 1979. Isolation and pure culture of a freshwater magnetic spirillum in chemically defined medium. J. Bacteriol. 140:720–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen H, Kuhnert P, Busse HJ, Frederiksen WC, Bisgaard M. 2007. Proposed minimal standards for the description of genera, species and subspecies of the Pasteurellaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:166–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeLong EF, Frankel RB, Bazylinski DA. 1993. Multiple evolutionary origins of magnetotaxis in bacteria. Science 259:803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Devouard B, et al. 1998. Magnetite from magnetotactic bacteria: size distributions and twinning. Am. Miner. 83:1387–1399 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frankel RB, Bazylinski DA, Johnson MS, Taylor BL. 1997. Magneto-aerotaxis in marine coccoid bacteria. Biophys. J. 73:994–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geelhoed JS, et al. 2009. Microbial sulfide oxidation in the oxic-anoxic transition zone of freshwater sediment: involvement of lithoautotrophic Magnetospirillum strain J10. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geelhoed JS, Kleerebezem RDY, Sorokin Stams AJ, van Loosdrecht MC. 2010. Reduced inorganic sulfur oxidation supports autotrophic and mixotrophic growth of Magnetospirillum strain J10 and Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1031–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonçalves RP, Bernadac A, Sturgis JN, Scheuring S. 2005. Architecture of the native photosynthetic apparatus of Phaeospirillum molischianum. J. Struct. Biol. 152:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grünberg K, Wawer C, Tebo BM, Schüler D. 2001. A large gene cluster encoding several magnetosome proteins is conserved in different species of magnetotactic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4573–4582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grünberg K, et al. 2004. Biochemical and proteomic analysis of the magnetosome membrane in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1040–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52:696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hall TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NY. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. (Oxf.) 41:95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jogler C, Schüler D. 2009. Genomics, genetics, and cell biology of magnetosome formation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:501–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jogler C, et al. 2009. Comparative analysis of magnetosome gene clusters in magnetotactic bacteria provides further evidence for horizontal gene transfer. Environ. Microbiol. 15:1267–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jogler C, et al. 2009. Toward cloning of the magnetotactic metagenome: identification of magnetosome island gene clusters in uncultivated magnetotactic bacteria from different aquatic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3972–3979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jogler C, et al. 2011. Conservation of proteobacterial magnetosome genes and structures in an uncultivated member of the deep-branching Nitrospira phylum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:1134–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Komeili A. 2012. Molecular mechanisms of compartmentalization and biomineralization in magnetotactic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36:232–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a. Lane DJ. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p 115–175 In Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M.(ed), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lang C, Schüler D. 2008. Expression of green fluorescent protein fused to magnetosome proteins in microaerophilic magnetotactic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4944–4953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lefèvre CT, et al. 2011. A cultured greigite-producing magnetotactic bacterium in a novel group of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Science 334:1720–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lefèvre CT, Viloria N, Pósfai M, Frankel RB, Bazylinski DA. 2012. Novel magnetite-producing magnetotactic bacteria phylogenetically affiliated with the Gammaproteobacteria class. ISME J. 6:440–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lohße A, et al. 2011. Functional analysis of the magnetosome island in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense: the mamAB operon is sufficient for magnetite biomineralization. PLoS One 6:e25561 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maratea D, Blakemore RP. 1981. Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum sp. nov., a magnetic spirillum. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 31:452–455 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsunaga T, Sakaguchi T, Tadokoro F. 1991. Magnetite formation by a magnetic bacterium capable of growing aerobically. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:651–655 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meldrum FC, Heywood BR, Mann S, Frankel RB, Bazylinski DA. 1993. Electron microscopy study of magnetosomes in two cultured vibrioid magnetotactic bacteria. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 251:237–242 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murat D, Quinlan A, Vali H, Komeili A. 2010. Comprehensive genetic dissection of the magnetosome gene island reveals the step-wise assembly of a prokaryotic organelle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:5593–5598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakazawa H, et al. 2009. Whole genome sequence of Desulfovibrio magneticus strain RS-1 revealed common gene clusters in magnetotactic bacteria. Genome Res. 19:1801–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schleifer KH, et al. 1991. The genus Magnetospirillum gen. nov. Description of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense sp. nov. and transfer of Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum to Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum comb. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 14:379–385 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schübbe S, et al. 2003. Characterization of a spontaneous nonmagnetic mutant of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense reveals a large deletion comprising a putative magnetosome island. J. Bacteriol. 185:5779–5790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schübbe S, et al. 2009. Complete genome sequence of the chemolithoautotrophic marine magnetotactic coccus strain MC-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4835–4852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schüler D. 2002. The biomineralization of magnetosomes in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Int. Microbiol. 5:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schüler D. 2008. Genetics and cell biology of magnetosome formation in magnetotactic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:654–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schüler D, Spring S, Bazylinski DA. 1999. Improved technique for the isolation of magnetotactic spirilla from a freshwater sediment and their phylogenetic characterization. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schultheiss D, Schüler D. 2002. Development of a genetic system for Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Arch. Microbiol. 179:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Spiridonova EM, et al. 2004. An oligonucleotide primer system for amplification of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes of bacteria of various taxonomic groups. Microbiology 73:316–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tamura K, et al. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Taoka A, et al. 2006. Spatial localizations of Mam22 and Mam12 in the magnetosomes of Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum. J. Bacteriol. 188:3805–3812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thrash JC, Ahmadi S, Torok T, Coates JD. 2010. Magnetospirillum bellicus sp. nov., a novel dissimilatory perchlorate-reducing alphaproteobacterium isolated from a bioelectrical reactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4730–4737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ullrich S, Kube M, Schübbe M, Reinhardt R, Schüler D. 2005. A hypervariable 130-kilobase genomic region of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense comprises a magnetosome island which undergoes frequent rearrangements during stationary growth. J. Bacteriol. 187:7176–7184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Williams TJ, Lefèvre CT, Zhao W, Beveridge TJ, Bazylinski DA. 2 December 2011. Magnetospira thiophila, gen. nov. sp. nov., a new marine magnetotactic bacterium that represents a novel lineage within the Rhodospirillaceae (Alphaproteobacteria). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1099/ijs.0.037697-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wolfe RS, Thauer RK, Pfennig NA. 1987. A “capillary racetrack” method for isolation of magnetotactic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:31–35 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wolin EA, Wolin MJ, Wolfe RS. 1963. Formation of methane by bacterial extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 238:2882–2886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.