Abstract

Fuschna Spring in the Swiss Alps (Engadin region) is a bicarbonate iron(II)-rich, pH-neutral mineral water spring that is dominated visually by dark green microbial mats at the side of the flow channel and orange iron(III) (oxyhydr)oxides in the flow channel. Gradients of O2, dissolved iron(II), and bicarbonate establish in the water. Our goals were to identify the dominating biogeochemical processes and to determine to which extent changing geochemical conditions along the flow path and seasonal changes influence mineral identity, crystallinity, and microbial diversity. Geochemical analysis showed microoxic water at the spring outlet which became fully oxygenated within 2.3 m downstream. X-ray diffraction and Mössbauer spectroscopy revealed calcite (CaCO3) and ferrihydrite [Fe(OH)3] to be the dominant minerals which increased in crystallinity with increasing distance from the spring outlet. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis banding pattern cluster analysis revealed that the microbial community composition shifted mainly with seasons and to a lesser extent along the flow path. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis showed that microbial communities differ between the flow channel and the flanking microbial mat. Microbial community analysis in combination with most-probable-number analyses and quantitative PCR (qPCR) showed that the mat was dominated by cyanobacteria and the channel was dominated by microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers (1.97 × 107 ± 4.36 × 106 16S rRNA gene copies g−1 using Gallionella-specific qPCR primers), while high numbers of Fe(III) reducers (109 cells/g) were identified in both the mat and the flow channel. Phototrophic and nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers were present as well, although in lower numbers (103 to 104 cells/g). In summary, our data suggest that mainly seasonal changes caused microbial community shifts, while geochemical gradients along the flow path influenced mineral crystallinity.

INTRODUCTION

Chalybeate waters are mineral spring waters containing high concentrations of reduced iron [Fe(II)] of typically up to 200 μmol liter−1 (see reference 15 and references therein). Geochemical gradients of O2 and Fe(II) form when the anoxic Fe(II)-rich groundwater reaches the surface. While the water equilibrates with the environment, bacterial communities establish and thrive utilizing the geochemical gradients of Fe(II) and O2.

Several physiological groups of microorganisms can gain energy by Fe(II) oxidation at neutral pH, including not only microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers (16) but also phototrophic (70) and nitrate-reducing Fe(II)-oxidizing (57) microorganisms. Photoferrotrophs are restricted to the photic zone (70). Nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers can live under anoxic conditions, for example, in lake sediments (31) or soils (48), but their occurrence and distribution depend on the availability of nitrate as an electron acceptor. Although molecular oxygen oxidizes Fe(II) chemically at circumneutral pH (10), microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers compete successfully with chemical oxidation in environments with low concentrations of molecular oxygen, e.g., in environments of opposing gradients of oxygen and Fe(II) (16).

Fe(III) produced by Fe(II) oxidation, either chemically or microbiologically, is poorly soluble at neutral pH and precipitates rapidly (10, 53). Fe(III) minerals that precipitate chemically under laboratory conditions are different from Fe minerals that form abiotically or biotically in nature. In the environment, iron minerals are usually less crystalline and contain substantial amounts of impurities, e.g., phosphate or cations but also organic matter (7, 8, 18, 19, 38, 39). These Fe(III) minerals can be used as electron acceptors by Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (35). It was shown that Fe(III) minerals produced by bacterial Fe(II) oxidation are better electron acceptors for Fe(III) reducers than chemically synthesized Fe(III) minerals (59). Depending on the availability of organic matter, bacterial Fe(III) reduction can occur at high rates (35), leading to a sufficient supply of Fe(II) for Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria. Therefore, an interplay between Fe(II) oxidation and Fe(III)-reducing bacteria at locations with high iron concentrations likely results in local microbial Fe cycling (22, 52, 55, 66).

To date, only a few studies have addressed the geomicrobiology of chalybeate surface waters, i.e., locations where Fe(II)-rich water reaches the oxic zone (5, 13, 28, 44, 45, 63, 65). These previous studies characterized the microbiology at various field sites and documented the presence of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers, Fe(III) reducers, and cyanobacteria but missed out on simultaneously characterizing phototrophic or nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers. However, the complex interplay between these different metabolic groups, the seasonal and spatial changes of geochemical parameters and microbial communities, and the identity and properties of the precipitating minerals have so far not been investigated in a single study.

In order to elucidate the interactions of geochemistry, mineralogy, and microbiology at a chalybeate spring, we investigated the circumneutral bicarbonate iron(II)-rich Fuschna Spring in the Engadin region of the Swiss Alps. This spring is one of several other springs in the Engadin which are characterized by either high bicarbonate or high sulfate concentrations (3, 6). CO2 in the water originates from metamorphic reactions in the Earth's crust (3, 56), and the other ions in the water result from mineral dissolution (6). The geological setting of Fuschna Spring suggests a meteoric origin of the spring water (56).

The main goals of this study were to identify and evaluate the geochemical factors and biogeochemical processes which determine the spatial and temporal distribution of microorganisms as well as the mineral identity and crystallinity of Fuschna Spring. For this purpose, samples were collected in various seasons and subjected to an array of geochemical, microscopic, spectroscopic, molecular, and microbiological analyses: (i) minerals were identified by Mössbauer spectroscopy, (ii) cell numbers were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and most-probable-number (MPN) counts, (iii) the microbial diversity was investigated using comparative sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes, and (iv) shifts in the microbial community composition were monitored by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and linked to changes in geochemical parameters by statistical clustering methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location of Fuschna Spring.

The field site is located at 46°47′16.62″N and 10°15′52.28″E near Scuol, Switzerland, at an elevation of 1,260 m above sea level. The water of the spring is classified as bicarbonate and ferrous iron rich (2, 67). Samples were taken five times over the course of 1 year (April, June, and August 2009; February and May 2010).

Sampling.

Samples were collected at three different locations at the spring, i.e., at the spring outlet (0 m), 1.2 m downstream from the outlet, and 2.2 m from the outlet (Fig. 1). At all sample locations, water flow was sufficient for collecting liquid samples for geochemical analyses. The delivery rate of the spring was determined by measuring the amount of water released from the spring outlet with a volumetric beaker (n = 10, 250 ± 20 ml) over time.

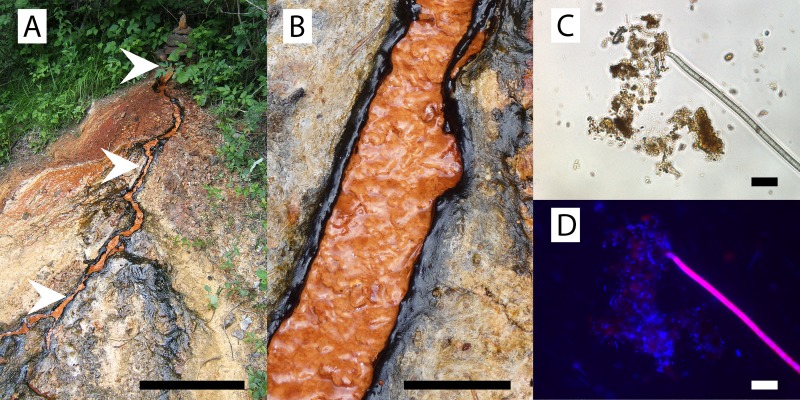

Fig 1.

Photographs and light microscopy images of Fuschna Spring. (A) Overview. Arrowheads, sampling locations. Bar, 1 m. (B) Closeup of the stream with cyanobacterial mats and minerals precipitates about 1.2 m downstream from the spring outlet. Bar, 5 cm. (C) Representative light microscopy image of a sample from the cyanobacterial mat 1.2 m downstream from the spring outlet. Bar, 25 μm. (D) Epifluorescence microscopy image of panel C. DAPI-stained signal (blue) overlaid with the autofluorescence signal of cyanobacteria (pink).

At all three locations, the flow channel and microbial mats at the side were distinctly separated (Fig. 1). Samples for geochemical analyses were taken from the flowing water, while samples for community analysis were taken from the solid material in the center of the flow channel and from the microbial mat at the sides of the channels. Mineral analysis was performed from the solid material collected from the flow channel. Beyond 2.2 m, the flow channel split up as a delta or was even overgrown by cyanobacterial mats, and a distinct differentiation between flow channel and mat was difficult (Fig. 1). Therefore, beyond 2.2 m from the spring outlet, no samples for geochemical and mineralogical analyses were taken. Sampling for geochemical analyses was not possible in February 2010, as the water was mostly frozen. Samples were collected using sterile plastic- or glassware. Samples for MPN analyses and microcosms were stored at 4°C until use (less than 4 days). Samples for molecular biological analyses were frozen immediately on dry ice and stored in the laboratory at −20°C until extraction.

Geochemical analysis of water samples.

O2 was quantified in the field with a handheld oximeter (WTW Oxi 315i), while temperature and pH values were determined with a pH meter (Eutech pH 310). All samples for laboratory analysis were stored at 4°C until use. Samples for bicarbonate and carbonate analyses were collected in brown 250-ml gastight screw-cap bottles. Titrations for phenolphthalein alkalinity (i.e., CO2) and H2CO3 were done with a Metrohm Titrino 836 titrator using dynamic titration. The titrants were either 0.1 N HCl up to pH 4.5 for the total alkalinity and 0.1 N NaOH up to pH 8.3 for the phenolphthalein alkalinity (14). Water samples for quantification of ferrous and ferric iron were immediately acidified with 1 M HCl. Fe(II) and total Fe (Fetot) were quantified spectrophotometrically by the ferrozine assay, as described previously (26). Samples for quantification of dissolved ions by ion chromatography were collected in 50-ml Falcon tubes and analyzed on a Dionex DX-120 ion chromatograph equipped with an autosampler, an AS23 anion column, and a CS 12A cation column. All samples were measured in duplicate and analyzed with the Chromeleon software package.

Mineral analysis.

Mineral samples were transferred into 10 ml rubber-stoppered serum flasks. In order to minimize potential oxidation of Fe(II) minerals, the samples were frozen on site using dry ice and later on were thawed and dried in an anoxic glove box (100% N2) in the laboratory before X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Mössbauer spectroscopy analysis. In addition to the sampling locations described above (0, 1.2, and 2.2 m from the spring outlet), additional samples at 0.7, 1.8, and 4.0 m from the spring outlet were collected for XRD measurements. The Fe(II)tot and Fe(III)tot in mineral samples were determined by dissolving the minerals with 6 M HCl in an anoxic glove box and quantifying the iron concentration of the sample as described in reference 26.

For mineral identification by XRD, dried samples were resuspended in 500 μl of 100% ethanol in an anoxic glove box, ground with a small mortar, and finally added onto a silicon waver. The samples were stored under anoxic conditions until analysis. During the analysis (<15 min), the samples were briefly exposed to air. XRD patterns were acquired with a Bruker D8 Discovery X-ray diffractometer with Co Kα radiation at 30 kV (30 mA) connected to a polycapillary focused to a spot size of 300 μm. Three overlapping frames of 30° 2 θ with a collection time of 1 min per frame were acquired with a general area detector diffraction system. Diffrac plus EVA (version 10.0.1.0) software (Bruker) was used for merging the frames and identifying the mineral phases using the PDF database (International Centre for Diffraction Data [ICDD]).

For Mössbauer spectroscopy, the dried mineral samples were embedded in Kapton tape in an anoxic glove box. The samples were analyzed in a Mössbauer spectrometer (Wissenschaftliche Elektronik GmbH, Germany) with a 57Co source embedded within a rhodium matrix. Linear acceleration was used in transmission mode using a constant-acceleration drive system set to a velocity range of ±12 mm s−1 with movement error of <1%. The absorption was determined with a 1024 multichannel analyzer. We varied the temperature of the sample with a Janis cryostat (Janis Research Company Inc.). The calibration of the spectra was done with an α-Fe(0) foil. Recoil software (University of Ottawa, Canada) was used for spectrum analysis. All models were analyzed using Voigt-based spectral lines.

Most-probable-number counting and Fe(III) reduction rates.

In order to determine the number of bacteria that could either reduce Fe(III) or oxidize Fe(II), we used the culture-dependent most-probable-number counting technique (9). Mineral medium was designed to resemble the spring water and contained 1.25 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.07 mM KH2PO4, 0.3 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, and 0.3 mM NaNO3. Additionally, 0.1 ml liter−1 sterile-filtered vitamin solution (69), 1 ml liter−1 sterile trace element solution (64), and 1 ml liter−1 sterile selenate-tungstate solution (68) were added. NaHCO3 (35 mM) was used as the buffer. The pH was adjusted to 6.3 to 6.4, similar to that of the spring water. The preparation of the anoxic medium followed standard procedures as described previously (26).

The environmental samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 3,000 × g to remove excess water from the wet solids, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of the designed medium. A 10-fold dilution series of the sample in medium was prepared and used to inoculate a 96-well deep-well plate (1 ml/well; seven parallels per sample). For Fe(III) reducers, 10 mM ferrihydrite and a mixture of 5 mM lactate and 5 mM acetate were added. Ferrihydrite was chemically synthesized (49), washed four times with Millipore water, and deoxygenated by repeated evacuation and flushing with N2. Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria were quantified by adding 10 mM FeCl2 and then exposing the plate to light (photoferrotrophs) or by additionally adding 10 mM Na nitrate following incubation in the dark for the quantification of autotrophic nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers. For mixotrophic nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers, 5 mM Na acetate was also added. After 12 weeks of incubation, oxidation of Fe(II) was determined visually (positive wells developed a rusty brown color), while Fe(III) reduction was evaluated by analyzing Fe(II) formation. Therefore, 150 μl ferrozine solution was mixed with 50 μl of each sample. Data evaluation was done as described by Klee (32).

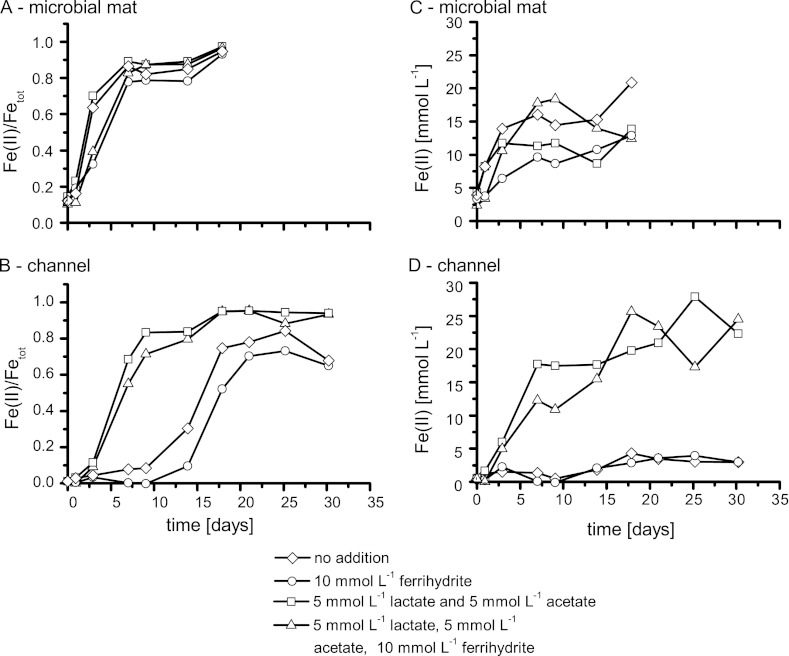

Fe(III) reduction rates at the three different locations of the spring were quantified in microcosms in 10-ml test tubes. One gram of centrifuged sample material (5 min at 3,000 × g) was added anoxically to 9 ml spring water. Setups with four different amendments and three parallels each were prepared. The different setups were (i) 10 mM ferrihydrite plus a mixture of 5 mM Na acetate and 5 mM Na lactate, (ii) 10 mM ferrihydrite, (iii) a mixture of 5 mM Na acetate and 5 mM Na lactate, or (iv) no additions. The concentrations of Fe(II) and Fetot were followed over time as described previously (26). Rates of reduction were determined by linear fitting of the steepest part of each reduction curve.

Extraction and amplification of environmental DNA.

Total DNA was extracted from 2.5 g of sample using the method of Zhou et al. (71). Crude DNA extracts were further purified using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Domain-specific primers were used to amplify almost full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences from the extracted chromosomal DNA by PCR (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material). PCRs were performed in a final volume of 50 μl: 0.2 μM each primer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 300 mg of bovine serum albumin, 1× PCR buffer, and 1.25 U of GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). Template DNA (20 ng) was added to the reaction mixture.

For DGGE, PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 2 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min with a decrease of 0.5°C after each cycle, and 72°C for 1 min; and 20 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min. For the clone library, PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, hot start at 70°C, and then 25 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min.

Quantitative real-time PCR and data analysis.

The absolute quantification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies was performed by using SsoFast Eva green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany) and 16S rRNA gene group-specific primers (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material), in combination with an iQ5 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany). We used the general bacterial primers 341F (41) and 797R (42) to quantify total Bacteria and primers GAL214F and GAL384R to quantify Gallionella relatives (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material). Each reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 μl consisting of 1× SsoFast Eva green mix and, depending on the assay, 75 nmol of primer 341F and 225 nmol of primer 797R or 500 nmol of primers GAL214F and GAL384R, together with 2 μl of sample or standard DNA. Sterile water and DNA of plasmid pCR4 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) without an insert were used as negative controls to ensure identification of false-positive amplification. PCR amplification and detection were conducted as follows: 2 min at 98°C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 98°C and 12 s at 60°C.

The data were analyzed with iQ5 optical system software, version 2.0 (Bio-Rad). As a standard, a cloned Gallionella sp. 16S rRNA gene fragment from the constructed bacterial clone library of Fuschna Spring was used (clone Fuschna-P4-E07; GenBank accession no. HE804146). qPCR was performed on two independent DNA extractions of each sample. All reactions were performed in triplicate.

DGGE.

In order to analyze cyanobacterial and bacterial community structure, we used DGGE (23). 16S rRNA gene group-specific primers were used (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material), and PCR conditions were the same as those described above. Briefly, we used a 6% acrylamide gel with a denaturing gradient of formamide and urea ranging from 35 to 60%. Analysis of the banding pattern was done with GelCompar II software, version 6.00 (Applied Maths). The unweighted-pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) was used to analyze the banding pattern of the gels using the following parameters: optimization of 2% and tolerance of 1%.

Clone library construction and analysis.

For clone library construction, products of three parallel PCRs were combined and purified with a Wizard DNA cleanup kit (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR products were ligated in the pCR4 TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Sequencing was performed using the vector primers M13F and M13R. Partial reads were assembled using the program DNA Baser. Chimeric sequences were eliminated from the clone libraries using the program Bellerophon (http://comp-bio.anu.edu.au/bellerophon/bellerophon.pl). Sequence data were aligned with the SINA web aligner (47) (http://www.arb-silva.de/aligner) and analyzed with the software packages ARB (37) and Mothur (54).

Microscopy.

Light microscopy images were taken on a Zeiss Axioscope 2 plus epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) with a ×40 objective lens. Fluorescent images of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-stained samples were taken with an excitation wavelength below 395 nm and an emission wavelength between 420 and 470 nm. The autofluorescence of cyanobacteria was detected by exposing the sample to a wavelength of between 395 and 440 nm and detecting the emission at a wavelength of >470 nm. Images of autofluorescence and DAPI fluorescence were overlain using the FIJI software package (http://pacific.mpi-cbg.de).

Geochemical modeling.

Geochemical modeling for carbonate mineral precipitation was performed with the Geochemists Workbench (version 6.0) software package (Rockware) using the React module (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The measured ion concentrations (see Table S4 in the supplemental material) were used as input to calculate mineral saturation indices under the experimentally determined geochemical conditions. Temperature was kept constant, while the pH increase of the water was taken into account. Additionally, Fe(II) oxidation and Fe(III) reduction rates were calculated for the water in the flow channel (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We used the following constants and estimates: water temperature and pH were as measured (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Chemical oxidation was estimated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where t is time. k1 was calculated using the equation (60)

| (2) |

where pO2 is partial O2 pressure. The constant k, which was equal to 1.47 × 1015 M−1 atm−1 min−1, was taken from Sung and Morgan (62). The residence time of the water in the flow channel (calculated from the delivery rate and the average width of the channel) was used to estimate the flow rate and thus the time during which the Fe(II) could be oxidized.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Representative sequences of each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers HE804132 to HE804167.

RESULTS

Geochemistry and mineralogy at Fuschna Spring.

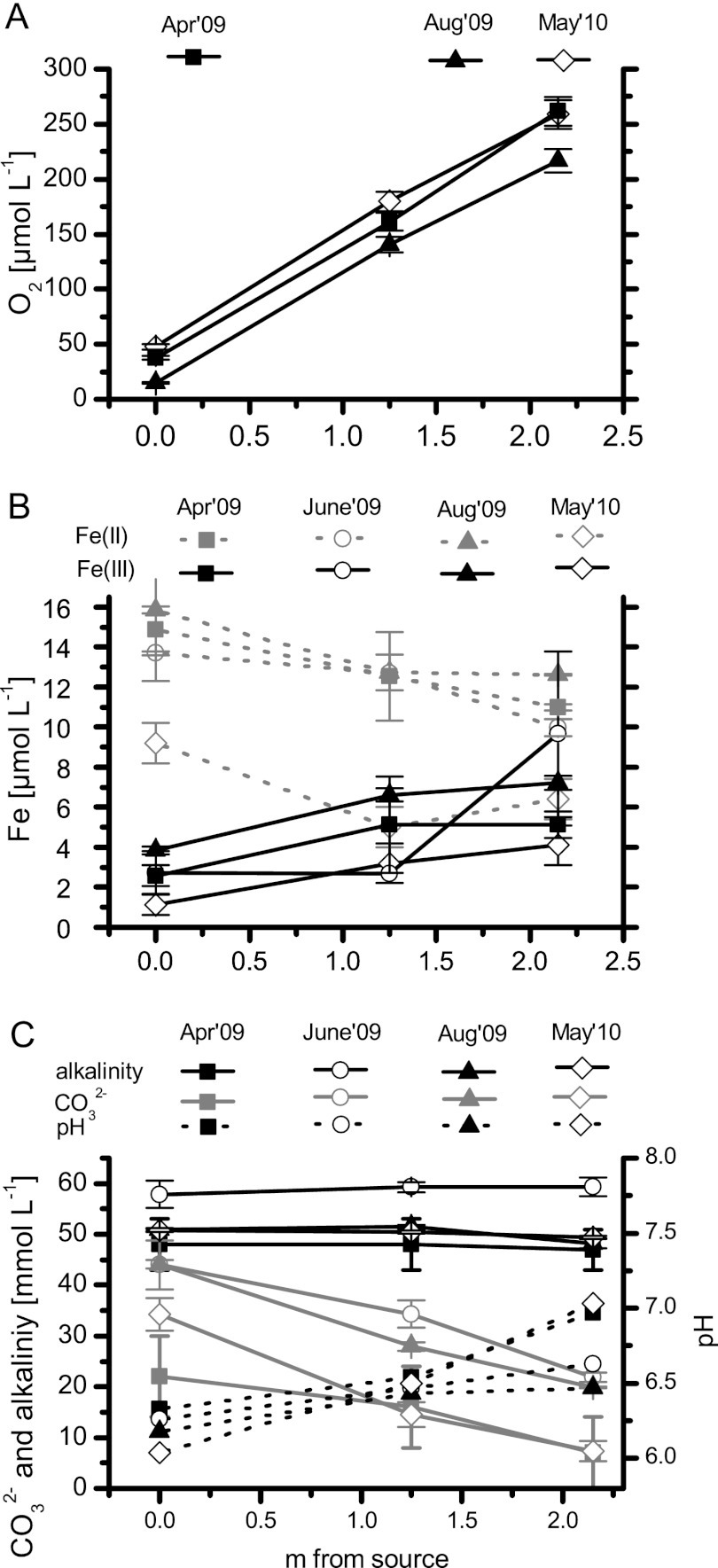

Fuschna Spring is an iron carbonate-rich spring with a water delivery rate of between 0.7 ± 0.1 and 1.2 ± 0.1 liters min−1. A narrow flow channel of 7 to 10 cm in width held most of the water (Fig. 1). On both sides of the stream, a 0.5- to 1-cm-thick dark green microbial mat flanked the flow channel (Fig. 1). With increasing distance from the spring outlet, the water channel divided into multiple subchannels. Depending on the season and extent of the microbial mats, no distinct channel was visible at about 2.3 m from the spring outlet and below. The dissolved O2 concentration in the water increased from 15 μM (microoxic) at the spring outlet to 260 μM (85% saturation at 14°C) at about 2.3 m downstream (Fig. 2). While the O2 concentrations increased with distance from the spring outlet, no significant variations in O2 concentration were observed between sampling campaigns (April to August 2009 and May 2010). The water temperature at the outlet of the spring varied from 8.1 to 10.8°C over the course of the sampling campaigns. Along the flow path, we detected a temperature increase of from 10.8°C to 14.5°C at 2.2 m from the spring outlet in August 2009, while at the other sampling times, the temperature did not increase more than 1°C. The pH at the spring outlet ranged from 6.0 to 6.3 and increased to pH values of from 6.7 to 7.0 at a distance of 2.3 m (Fig. 2). The maximum pH increase from the spring outlet to the location 2.3 m downstream during one particular sampling campaign was 0.9.

Fig 2.

Geochemical parameters of the spring water with increasing distance from the spring outlet. (A) Oxygen concentration in the stream water at four different time points; (B) Fe(II) and Fe(III) concentrations determined in the water of the stream at four time points; (C) alkalinity, carbonate concentration, and pH at three different time points.

The concentration of total Fe(II) in the spring water decreased slightly downstream from the spring outlet. Values ranged from 12 to 16 μM at the spring outlet to 10 to 14 μM at a distance of 2.2 m downstream and did not show significant deviations at the different sampling campaigns (Fig. 2). At the spring outlet, 80% of the iron in the water was present as Fe(II). The total concentration of Fe(III) in the water, probably including dissolved Fe(III), complexed Fe(III), as well as Fe(III) colloids, increased with distance from the spring outlet and reached values of 4 to 10 μM (Fig. 2). A comprehensive geochemical analysis of the spring water showed that the ion concentrations in the water did not change significantly over time (data not shown). A representative list of the ions detected in the spring water in August 2009 is shown in Table S4 in the supplemental material. The main ions were calcium (17.4 mM) and magnesium (2.2 mM). The total alkalinity of the water ranged from 52 to 58 meq liter−1 (Fig. 2), with the major relevant component of the spring water being CO2, which had a concentration at the spring outlet of 44 mM. The contribution of other ions to the alkalinity was minor due to their relatively low concentrations (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

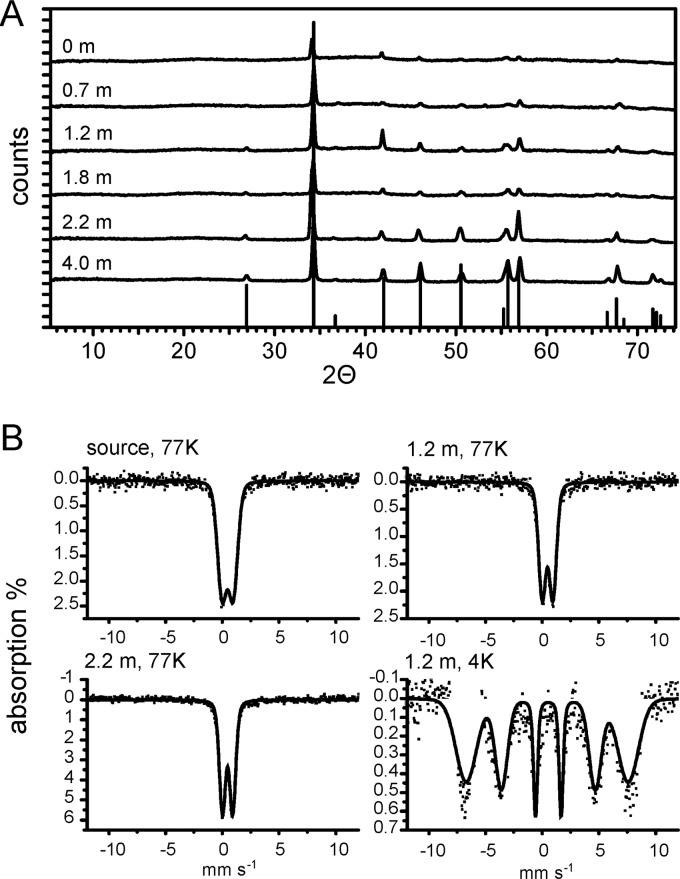

In order to determine which carbonate minerals are expected to precipitate under the geochemical conditions measured, thermodynamic equilibrium modeling for calcite (CaCO3), dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2], and siderite (FeCO3) precipitation was done considering the concentrations of all ions detected in the water. The calculations suggested that the main mineral expected to precipitate is calcite (CaCO3) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This is due to the high concentrations of calcium and bicarbonate in the mineral water (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Fe(II) carbonates (e.g., siderite, FeCO3) are expected to precipitate only at pH values above pH 6.7. Calcite oversaturation was higher than that of dolomite and siderite. Therefore, precipitation of the last two minerals is expected to be less than that of calcite. XRD analysis of samples collected at increasing distances from the spring outlet confirmed that the main crystalline mineral phase present was indeed calcite at all sampling locations (Fig. 3). With increasing distance from the spring outlet, the crystallinity of calcite increased, as evidenced by the increasing height and sharpness of the reflections, for example, at 2 θ values of 27 and 57, respectively (Fig. 3). Neither dolomite, siderite, nor any other Fe(II) or Fe(III) minerals were detected with XRD at any location. The absence of signals for these minerals in XRD could be due to the small amounts of these minerals in the samples (XRD has a detection limit of approximately 5 to 10%). Additionally, acid Fe extraction followed by spectrophotometric analysis of the solids showed no Fe(II), and therefore, Fe(II) minerals are not expected to be present. However, acid extraction of the solids yielded a concentration of Fe(III) in dry sediment samples of 1.5 to 2.5% (wt/wt) independent of the location (e.g., 0 m from the spring outlet to 2.2 m downstream). We thus analyzed these samples by Mössbauer spectroscopy (Fig. 3; see Table S2 in the supplemental material), which is selective for iron and, in contrast to XRD, is also able to detect poorly crystalline mineral phases. As expected, Mössbauer spectroscopy did not detect any Fe(II) mineral phases, confirming the absence of Fe(II) in the mineral phase. However, a poorly crystalline Fe(III) mineral phase that fit best with a chemically synthesized ferrihydrite standard was detected in the solids (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The crystallinity of these Fe(III) minerals increased with distance from the spring outlet, as reflected in the narrower peak width of the Mössbauer spectra in samples collected at increasing distance from the spring outlet (Fig. 3). These changes can also be calculated and are expressed by the decrease in the σΔ parameter (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

(A) Representative X-ray diffractograms of mineral samples collected downstream of the spring outlet. At the bottom, the reference for calcite is shown (powder diffraction file 00-005-0586). The samples were collected in August 2009. (B) Mössbauer spectra measured at 77 K from samples collected in August 2009 at three different distances from the spring outlet. For the sample collected at 1.2 m downstream, an additional spectrum was collected at 4 K. Red lines, fitted model results. For Mössbauer parameters, see Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Calculations of chemical Fe(II) oxidation rates on the basis of O2 and Fe2+ concentrations, flow rate, and pH (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were performed in order to evaluate whether chemical Fe(II) oxidation plays a significant role at this field site. These calculations show that chemical oxidation is expected to decrease the amount of Fe(II) in the water much faster than we were observing. While calculations suggest a final concentration of Fe(II) of 0.2 μM at about 2.2 m from the spring outlet, we still observed a final concentration of about 13 μM, suggesting either slower oxidation rates or an additional source of Fe(II), e.g., microbial Fe(III) reduction (see below).

Abundance of Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing microorganisms.

The water channel at the spring was flanked by dark green to blackish mats, while the mats were not observed within the orange-colored flow channel (Fig. 1). Light and epifluorescence microscopy showed the presence of both bacteria and filamentous structures—cyanobacteria—in the mat (Fig. 1C and D). Bacterial cell numbers were determined in samples collected in April 2009 and May 2010 from the mat and in the flow channel with MPN counts for Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (see below) and with qPCR for one sample collected in August 2009. We quantified the number of bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies with qPCR using broad-range bacterial primers (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material). Gene copy numbers were 2.02 × 108 ± 3.18 × 107 copies g−1 (wet weight) in the middle of the flow channel, while we quantified 1.97 × 108 ± 3.05 × 107 copies g−1 (wet weight) within the microbial mat. Both samples were taken at 1.2 m from the spring outlet. In this context, it is important to consider that qPCR most likely underestimated the total number of 16S rRNA gene copies from the microbial mat because the broad-range bacterial primers used did not optimally target all cyanobacterial taxa. This is also reflected by the low representation of cyanobacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences in the clone library (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). We therefore used more specific cyanobacterial primers for the DGGE analysis (results are discussed below).

Using primers specific for Gallionella (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material), one important group of microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria, we found 1.97 × 107 ± 4.36 × 106 copies g−1 in the middle of the flow channel 1.2 m from the spring outlet, suggesting an important role of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidation within the flow channel. In contrast, the number of 16S rRNA gene copy numbers obtained with the Gallionella-specific primers in the microbial mat was much lower (8.34 × 103 ± 4.21 × 103 copies g−1), suggesting a minor role of microbial Fe(II) oxidation in the green mats.

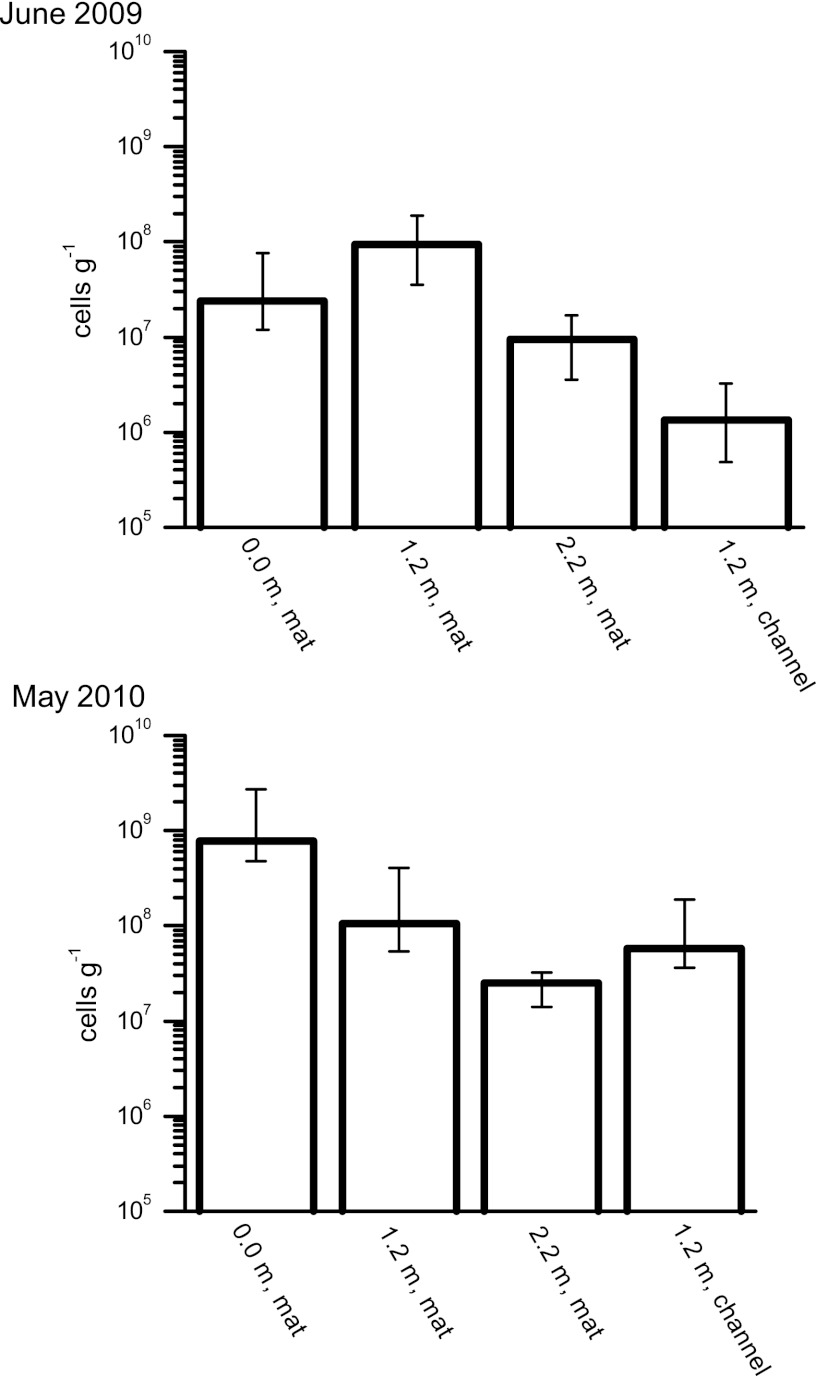

Using MPN counts, we quantified the number of nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers, phototrophic Fe(II) oxidizers, and anaerobic Fe(III) reducers. Samples for MPN counts of Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing bacteria were taken in late spring and early summer (June 2009 and May 2010) at the three locations corresponding to the geochemical sampling sites: right at the spring outlet and 1.2 and 2.2 m downstream. Furthermore, at 1.2 m from the spring outlet, we distinguished between the flanking microbial mat and the middle of the flow channel. At all other locations, only the microbial mat was sampled. The number of microorganisms able to oxidize Fe(II) phototrophically or coupled to the reduction of nitrate was always substantially less than the number of Fe(III) reducers (Fig. 4). Photoferrotrophs were found in numbers ranging from 103 to 104 cells g−1 (wet weight) sample. The numbers of nitrate-reducing Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria ranged from 103 to 104 cells g−1 sample. At some locations, even no nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers could be detected.

Fig 4.

Most-probable-number counts for Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (quantified with ferrihydrite and a mix of lactate and acetate). Samples were collected in June 2009 and in May 2010 at increasing distances from the spring outlet either from the microbial mat or from the flow channel. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals.

In contrast to Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria, Fe(III) reducers were much more abundant. Cell numbers in samples collected from the mat at all three sample locations in May 2009 were about 107 to 108 cells g−1 (wet weight) mat sample (Fig. 4). For samples taken in May 2010, the numbers of Fe(III) reducers were generally higher than those in 2009, in particular, in the mat at the spring outlet, with numbers of up to 109 cells g−1 (Fig. 4). Compared to the samples from the mat at the spring outlet, the numbers of Fe(III) reducers in the middle of the flow channel seemed to be slightly lower but still reached values of 107 to 108 Fe(III)-reducing cells g−1 (Fig. 4).

Quantification of Fe(III) reduction rates.

In order to estimate the production of Fe(II) by Fe(III) reducers, we determined rates of Fe(III) reduction in samples collected in September 2010 from the microbial mat and the flow channel at a 1.2-m distance from the spring outlet. The mat samples used for these experiments contained about 7.7 mg Fetot per g, while the samples from the flow channel contained about 8.9 mg Fetot per g (wet weight) material. After incubation of the samples in spring water under anoxic conditions, the samples collected from the mat showed rapid Fe(III) reduction without a significant lag time. The rate of Fe(III) reduction in the microbial mat was fastest in the pure mat samples without any additions [maximum rate, 5.5 ± 0.4 mM Fe(II) day−1]. Fe(II) formation rates did not increase significantly for setups amended with acetate and lactate (2.2 ± 0.3 mM day−1) or setups amended with acetate, lactate, and ferrihydrite (4.2 ± 0.4 mM day−1). The reduction rate was slowest when only additional ferrihydrite was added as the Fe(III) source [1.3 ± 0.1 mM Fe(II) day−1]. Extraction with 1 M HCl at the end of incubation showed that the noncrystalline (1 M HCl-extractable) iron in the four different mat microcosms was reduced almost completely to Fe(II), leading to ratios of Fe(II)/Fetot of 90 to 100% (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Reduction of Fe(III) in 1 g (wet weight) of sample collected from the spring. (A and C) Samples collected from the side of the stream; (B and D) samples collected from the middle of the channel. Samples were collected in summer 2010. (A and B) Fe(II)/Fetot; (C and D) Fe(II)tot. Due to the slightly different lag times, only one representative out of three parallels is shown.

In contrast to the samples collected from the microbial mat, unamended samples from the middle of the flow channel showed a prolonged lag phase of 6 to 8 days before significant concentrations of Fe(II) could be measured, with maximum reduction rates of 1.1 ± 0.1 mM Fe(II) day−1 and a maximum total reduction of approximately 80% detected. The addition of acetate and lactate reduced the lag phase from 6 to 8 days to 2 days, increased the maximum reduction rate to 2.7 ± 0.2 mM Fe(II) day−1, and led to the virtually complete reduction of 1 M HCl-extractable Fe(III) (Fig. 5). The addition of ferrihydrite led to an incomplete reduction of Fe(III) (reduction of up to 70%) and a reduction rate of 0.9 ± 0.2 mM Fe(II) day−1, while the simultaneous addition of ferrihydrite plus lactate-acetate led to maximum reduction rates of 2.3 ± 0.2 mM Fe(II) day−1. The concentration of bioavailable reducing equivalents present in the sample was calculated from the final amount of Fe(III) reduced in samples that were not amended with additional electron donors and was 4 to 5 mM electrons g−1 sample.

Microbial diversity at Fuschna Spring.

Samples for analysis of the microbial diversity were collected at the same locations as samples for the geochemical analysis, i.e., directly at the spring outlet and 1.2 and 2.2 m from the spring outlet, in April 2009, August 2009, and February 2010. We used DGGE to follow spatial and temporal shifts in the microbial community composition. The DNA from the samples was extracted and amplified with broad-range primers for Bacteria, Archaea, and cyanobacteria (primers and references are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material). With the general archaeal primers, no amplicon could be obtained under various PCR conditions.

DGGE banding patterns revealed relatively low cyanobacterial diversity in the microbial mats at the side of the flow channel. The DGGE gels showed one prominent band which was accompanied by an additional faint band in a few cases (a representative DGGE gel is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). A cluster analysis of the cyanobacterial diversity was therefore not performed. Samples from the flow channel showed the same cyanobacterial band that was dominant in the mat, but only very weak bands were observed. Reamplification, subcloning, and sequencing of the DGGE band revealed its close affiliation to “Tychonema bourrellyi” (99% sequence similarity) of the order Oscillatoriales. Sequences related to the same cyanobacterial taxa have also been found in the 16S rRNA gene clone library.

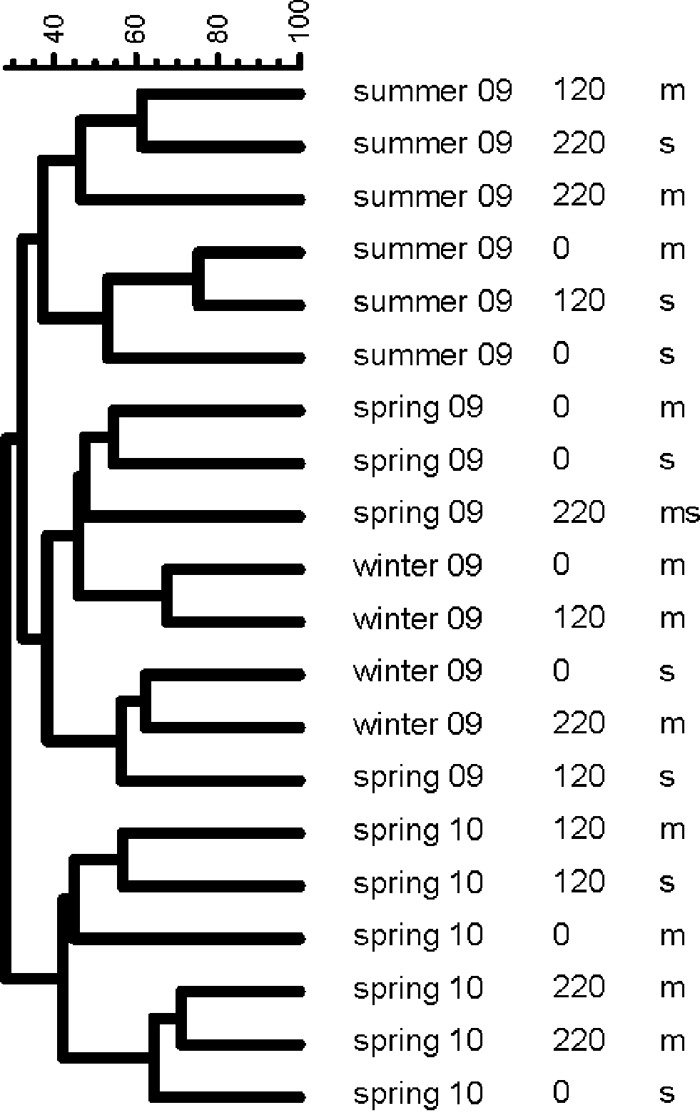

In contrast to the cyanobacterial diversity, general bacterial diversity was higher in both the microbial mat and the middle of the flow channel. In order to determine shifts in the bacterial community composition with time and along the flow path, a cluster analysis was performed (Fig. 6). The cluster diagram indicated that the composition of the microbial community did not change significantly with increasing distance from the spring outlet. However, the microbial community composition in the mat samples differed from that in the flow channel samples. The most pronounced differences in DGGE banding patterns were observed by comparing the different sampling dates. The UPGMA diagram (Fig. 6) shows three clearly separated clusters independent of sampling location (microbial mat or flow channel) and distance from the spring outlet: one for the later spring samples (May 2010), one for the summer samples, and a third cluster for the winter/earlier spring (February 2010 and April 2009) samples.

Fig 6.

Cluster analysis of the microbial communities at alternating seasons by UPGMA depicting the seasonal variations of DGGE banding patterns. Samples were collected four times (spring 2009 and 2010, summer 2009, winter 2010) either from the microbial mat (m) or from the flow channel (c). In one sample (cm), no distinction between channel and mat was possible.

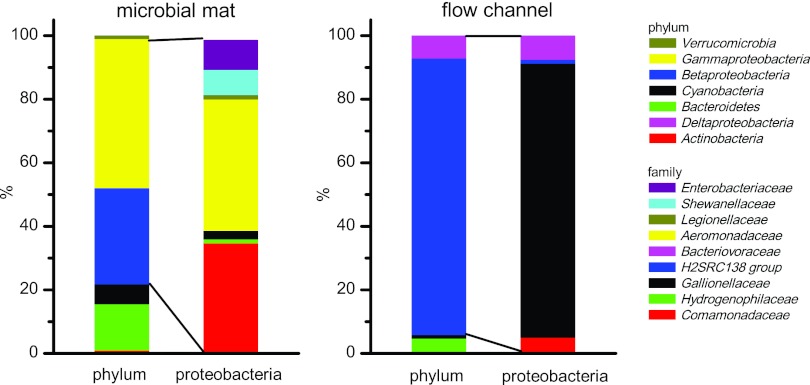

In order to study the microbial diversity in the mats and the flow channel in more detail, bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were constructed from mat and channel samples collected in August 2009 at 1.2 m from the spring outlet. In total, 181 clones were analyzed, 96 clones from the microbial mat and 85 clones from the flow channel. Comparative sequence analysis and calculation of diversity indices were based on a 97% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity criterion (27). In general, the diversity within the microbial mat was higher than that in the flow channel. In the flow channel, only 7 major OTUs were detected, whereas 21 OTUs were found in the microbial mat sample. Clone library coverage based on the Chao index was 77% for the microbial mat samples and 89% for the flow channel samples. Many Fuschna Spring clones showed a high similarity (>97%) to sequences of uncultivated microorganisms from other freshwater habitats. Thirty-two 16S rRNA gene clone sequences (GenBank accession numbers AB475010 to AB475041) are available from a previous yet unpublished study of Fuschna Spring from October 2005 by Kurt Hanselmann and colleagues, but only three of these were uncultivated relatives that were the closest to the clone sequences derived from the present study.

Both clone libraries were dominated by proteobacterial sequences, with 83% and 87% of total clones, respectively (Fig. 7). However, the diversity within the proteobacteria was higher in the microbial mat samples (11 OTUs) than the flow channel samples (4 OTUs). Clones related to bacteria involved in iron cycling were found in both clone libraries: most betaproteobacterial clones from the flow channel (1 OTU) were closely related to known Fe(II) oxidizers of the genus Gallionella (72% of total clones), but only a very few clones from the microbial mat (2% of total clones) grouped into this OTU. A large fraction of clones from the flow channel (29% of total clones) formed three distinct OTUs which were affiliated with known Fe(III) reducers of the genus Albidiferax.

Fig 7.

Normalized diversity of the bacterial communities determined by comparative 16S rRNA gene analysis. The samples were collected 1.20 m from the spring outlet in August 2009 either from the microbial mat (side) or from the flow channel (middle). The proteobacterial OTUs are shown on the family level. The microbial mat had 96 clones in total and 74 clones within the proteobacteria. The flow channel had 85 clones in total and 80 clones within the proteobacteria.

A large fraction of clones from the microbial mat (53% of total clones) was affiliated with the diverse group of gammaproteobacteria, but no gammaproteobacterial clone was found in the clone library from the flow channel. One OTU from the microbial mat (32% of total clones) was affiliated with Aeromonas punctata subsp. caviae (46). Two other OTUs, represented by 6% total clones each, were closely related (99% sequence similarity) to the known Fe(III) reducer Shewanella putrefaciens (43) and Buttiauxella noackiae (40), respectively.

All clones related to cyanobacteria fell in the order Oscillatoriales and grouped into one OTU which was the most closely related to Tychonema bourrellyi (99% sequence similarity) (1, 61). This OTU was more abundant in the clone library from the microbial mat (6% total clones) than in the clone library from the flow channel, where it was represented only by a singleton.

DISCUSSION

Fuschna Spring is characterized by a close association of O2-producing cyanobacteria and microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing bacteria which populate the flow channel and the adjacent microbial mat at an average in situ temperature of approximately 10°C. A similar ecosystem dominated by ferrous iron, iron-metabolizing microorganisms, and cyanobacteria with an absence of sulfide is the Chocolate Pots Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park, which, in contrast to the ecosystem investigated in the present study, is 50°C (44, 45, 63). However, in contrast to the Yellowstone springs, which showed mat layers of cyanobacteria associated with iron oxides where the cyanobacteria drive Fe(II) oxidation by supersaturation of the water with O2, Fuschna Spring can be divided into two distinct zones that are in close contact with each other (Fig. 1). The separation into these two zones probably results from the local flow regime (flow rates, etc.). In the following paragraphs, we discuss the biogeochemical processes occurring in these two distinct zones and focus on the adaptation and role of the microbial community with respect to the presence of ferrous and ferric iron.

Importance of Fe(III)-reducing microorganisms at Fuschna Spring.

The 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were of the same order of magnitude as the cell numbers of Fe(III) reducers determined by MPN counts. This suggests that Fe(III) reducers represent a significant fraction of all Bacteria and emphasizes the importance of microbial Fe(III) reduction at the field site. The importance of microbial Fe(III) reduction in the mat is supported by the very short lag phase observed in the Fe(III) reduction experiments, suggesting that the abundant Fe(III) reducers are also actively reducing Fe(III) in situ. The numbers of Fe(III) reducers were highest within the microbial mat (Fig. 4), while the cell numbers were slightly lower within the flow channel. The decrease in the number of Fe(III) reducers with distance from the spring outlet can be explained by the observed increase in crystallinity of Fe(III) minerals with increasing distance (Fig. 3; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The higher crystallinity of the Fe(III) minerals probably leads to a lower Fe(III) bioavailability and thus to a less favorable habitat for Fe(III) reducers.

Although the cell numbers of Fe(III) reducers were lower in the middle of the flow channel than in the mat, the overall numbers were still relatively high, considering that the availability of organic carbon was significantly lower in the channel than in the mat. Fe(III) reduction in the channel indeed seemed to be electron donor limited (see the next paragraph). This suggests that either the Fe(III) reducers in the middle were present but not active or they could switch between Fe(II) oxidation and Fe(III) reduction, similar to Geobacter metallireducens (17), and performed Fe(II) oxidation and not Fe(III) reduction in situ. Additionally, the number of Fe(III) reducers in the channel may have been overestimated by the MPN counts, because some of the microorganisms living in the channel may also be capable of using electron acceptors other than Fe(III) (e.g., O2). Shewanella putrefaciens, which was detected at the field site, is well-known to be metabolically versatile and is able to use electron acceptors other than Fe(III), e.g., molecular oxygen (20, 43).

Fe(III) reduction rates and electron donor availability/limitation at Fuschna Spring.

To determine the limiting factors of Fe(III) reduction at the spring, we measured Fe(III) reduction kinetics with and without amendment of electron donor or acceptor. Fe(III) reducers in the microbial mats were not limited by electron donor (Fig. 5), since Fe(III) reduction in the microcosms started without a significant lag phase. Further evidence comes from the facts that (i) reduction rates did not further increase after addition of acetate-lactate, (ii) complete reduction of Fe(III) was observed even in the absence of additional electron donor, and (iii) high Fe(II) concentrations were measured in the water. Fe(II) concentrations in the channel water were much higher than expected on the basis of calculated chemical Fe(II) oxidation rates, suggesting efficient Fe(III) rereduction leading to a constant Fe(II) replenishment (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Electron donors were probably available within the microbial mat due to microbial primary production by the cyanobacteria (44). However, due to the high organic carbon content, the availability of Fe(III) for Fe(III) reducers in the mats might be limiting. Addition of ferrihydrite, however, decreased the reduction rate from 5.5 ± 0.4 mM day−1 to 1.3 ± 0.1 mM day−1 after Fe(III) amendment (Fig. 5). This suggests that the Fe(III) in the microbial mats probably consisted to a significant extent of biogenic ferrihydrite, which was more bioavailable than the chemically synthesized ferrihydrite added to the microcosms. A similar preference for biogenic Fe(III) oxyhydroxides compared to synthetic Fe(III) minerals was described before (33, 58). The addition of ferrihydrite might also have caused inhibiting effects on microbial Fe(III) reduction, e.g., by nutrient sequestration or binding of electron shuttles, such as redox-active humic substances that might have been present in solution in situ and stimulated reduction of the Fe(III) minerals (29, 36).

In contrast to the Fe(III) reducers present in the mat, we found that Fe(III) reducers in the middle of the flow channel were not limited in Fe(III) but, rather, were limited in electron donor (Fig. 5). This is evidenced by the increase in reduction rates after acetate-lactate addition and by the lower extent of total Fe(III) reduction. Microcosms inoculated with samples from the flow channel reached only 60 to 80% without addition of electron donor, while in the adjacent mats, the Fe(III) reduction without organic carbon amendment was complete (100%). The carbon limitation in the flow channel is most likely due to the absence of cyanobacterial primary production and the low number of photoautotrophic Fe(II) oxidizers.

Budget of ferrous iron: evidence for Fe cycling.

The concentration of Fe(II) in the water is controlled by different processes functioning as either sources or sinks: (i) Fe(II) initially present in the spring water, (ii) Fe(II) from Fe(III) reduction in the microbial mat and flow channel, and (iii) chemical and microbial oxidation of Fe(II). Calculations of the chemical oxidation rates (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) suggest that the Fe(II) concentrations in the water should be much lower than those actually measured. This suggests that biological Fe(III) reduction is rapid and efficient, despite chemical and microbial Fe(II) oxidation, and provides evidence for effective Fe cycling in this habitat. The role of Fe(III) rereduction is probably even more important, since our calculation considered only abiotic homogeneous Fe(II) oxidation. Additionally, Fe(II) oxidation by O2 at the surface of precipitated Fe minerals and at the surface of microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria is expected to remove Fe(II) from the water even faster than chemical oxidation (12, 50). However, we observed that even the high numbers of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers present were not sufficient to remove all Fe(II) from solution. Due to their low numbers, nitrate-reducing and phototrophic Fe(II) oxidizers likely did not significantly influence the Fe(II) concentration in the water (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Overall, this suggests that organic carbon and O2 from cyanobacterial primary production in combination with O2 from the atmosphere lead to cycling of Fe(II) and Fe(III).

Microbial community structure in the mat and in the flow channel.

A higher diversity of the microbial mat than the flow channel was not unexpected because microbial mats are known to host a wide range of microorganisms with various metabolisms (34). Changes of the microbial community were observed by cluster analysis of the DGGE band patterns and showed that the dominant change in bacterial community composition happened over the course of the seasons and not with increasing distance from the spring outlet. The differences between the microbial mat and the flow channel were more significant than the variations occurring with increasing distance from the spring outlet (Fig. 6). Therefore, the following discussion on the microbial community composition not only refers to the respective sampling point at a 1.2-m distance from the spring outflow but also can be extended to the entire area of the spring at the respective time of sampling (summer 2009).

The high number of clones (34% of all proteobacteria) closely related to Albidiferax ferrireducens suggested a high potential for Fe(III) reduction within the microbial mats. This was also confirmed by our microcosm experiments (Fig. 5). Only a few clones related to the microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing Gallionella ferruginea were identified in the microbial mat. These results agree well with the qPCR data, which revealed only 8.34 × 103 ± 4.21 × 103 Gallionella sp. 16S rRNA gene copies g−1 in the microbial mat sample. Among the Shewanellaceae (6% of all bacterial clones in the mat library), many are known Fe(III) reducers. Shewanellaceae are also known to be metabolically versatile microorganisms which can thrive under many different environmental conditions in a complex stratified mat environment (20, 43). Among the Aeromonadaceae are many facultative pathogens which are known to be capable of a variety of different metabolisms, including nitrate reduction and the fermentative use of organic acids (46). The genus Buttiauxella, making up 6% of the total clones in the microbial mats, has also been described to be metabolically versatile (40). The cyanobacterial clones were all closely related, and they were 99% similar to Tychonema bourrellyi. These findings agree well with those of the DGGE analysis of the cyanobacterial diversity in the microbial mats, which indicated that the mats were dominated by only one species. Tychonema bourrellyi prefers oligotrophic to slightly eutrophic waters in rather cold environments (see references 1 and 61 and references therein), which resemble the geochemical settings at the field site.

In the samples collected from the middle of the flow channel, microaerophilic iron-oxidizing Gallionellaceae dominated the clone library (81% of all clones). Gallionella spp. are known to utilize oxygen to oxidize Fe(II) under microaerophilic conditions (25). Quantification of Gallionella 16S rRNA gene copy numbers showed that 10% of all Bacteria in the flow channel belonged to the Gallionellaceae. The geochemical conditions [e.g., elevated Fe(II) concentration and initially low O2 concentration] in the flow channel most likely meet their metabolic needs.

Microbial communities at other chalybeate springs.

Recently, chalybeate surface waters have been gaining more interest by the geomicrobiology community. James and Ferris (28) identified microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers in an iron-rich creek by their morphological properties and demonstrated an enhancement of the Fe(II) oxidation rate by the activity of the microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers. These authors described neither photoferrotrophs, nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers, nor Fe(III) reducers, simply because these strains do not have specific morphological features which would allow their microscopic differentiation. In the study of Wagner et al. (65), a clone library of a chalybeate spring with a high bicarbonate concentration similar to that of Fuschna Spring was constructed. The authors used proteobacterial 16S rRNA gene primers and identified several Gallionella and Leptothrix clones, again pointing toward the importance of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidation in such systems. Furthermore, they found in their clone library sequences of Rhodoferax fermentans, an Fe(III) reducer related to Albidiferax ferrireducens, which was also present in our clone library.

Gallionella and Leptothrix were also described at an Fe-Mn seep in a wetland (30), and studying chalybeate creek water of West Berry Creek, Duckworth et al. (13) also found Gallionella- and Leptothrix-related species. Further comparison of their clone library data with our data is difficult because the creek water had relatively high concentrations of total organic carbon (1.8 to 3.0 mg liter−1). Consequently, the diversity of the microbial community in the study of Duckworth et al. (13) was much higher than that in our study. They also detected Fe(III) reducers, in addition to the Fe(II) oxidizers, and concluded that the potential for microbial Fe cycling exists. Similar Fe cycling was suggested by Bloethe et al. (4) and Roden et al. (51) at iron-rich groundwater seeps.

Bruun et al. (5) found microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers belonging to the genera Gallionella and Sideroxydans in an iron-rich freshwater seep, while the dominant iron reducers belonged to the genus Geobacter. They found that a complex mixture of organic substrates (rotting leaves) was enhancing Fe(III) reduction better than the addition of acetate (5). These findings are comparable to our findings: Fe(III) reduction was delayed in samples collected from the flow channel compared to the Fe(III) reduction in the microbial mats, where a more complex mixture of organic substrates can be expected.

The results of the previous studies (5, 13, 28, 65) together with the results reported in this study suggest a strong contribution of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidizers to the oxidation of Fe(II) in iron- and bicarbonate-rich freshwater springs, while nitrate-reducing Fe(II) oxidizers and photoferrotrophs are likely contributing to a lesser extent to microbial iron oxidation in these habitats.

Conclusions.

In summary, Fuschna Spring is a well-defined ecosystem with a continuous supply of ferrous iron as well and other ions and nutrients through the spring water (including bicarbonate and small amounts of dissolved organic carbon but no sulfide). Therefore, primary production at the spring is dominated by two distinct processes: phototrophy, i.e., photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, and chemotrophy by microaerophilic oxidation of Fe(II). In turn, Fe(III) reduction is coupled to the breakdown of organic carbon produced by these microbial primary producers. Therefore, this ecosystem can serve as an excellent model system to study microbial iron cycling decoupled from the input of other sources of organic matter. Furthermore, this ecosystem may be used to study the interactions of microbially catalyzed microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidation with oxygen-producing cyanobacteria, processes proposed for the formation of banded iron formations starting at and after 2.3 to 2.7 gigaannum (Ga), when oxygen was present in low concentrations in the Earth's atmosphere (15, 21). Even the high bicarbonate concentration in the spring water (approximately 50 mmol liter−1) is similar to the concentration of bicarbonate suggested to be present in the Precambrian oceans (up to 70 mmol liter−1 [24]). Therefore, Fuschna Spring might also serve as a modern analog to study the role of iron-metabolizing bacteria in ancient Earth environments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Urs Dippon and Christian Schröder for their help with Mössbauer spectroscopy and data analysis, Inga Köhler and Christoph Berthold for their support with XRD measurements, Ellen Struve for ion chromatography measurements, and Karin Stögerer and Petra Kühner for help with molecular biology experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anagnostidis K, Komárek J. 1988. Modern approach to the classification system of cyanophytes. 3. Oscillatoriales. Arch. Hydrobiol. 80:327–472 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bissig P. 2004. Die CO2-reichen Mineralquellen von Scuol-Tarasp (Unterengadin, Kt. GR). Bull. Angew. Geol. 9:39–47 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bissig P, Goldscheider N, Mayoraz J, Surbeck H, Vuataz F-D. 2006. Carbogaseous spring waters, coldwater geysers and dry CO2 exhalations in the tectonic window of the Lower Engadine Valley, Switzerland. Eclogae Geol. Helv. 99:143–155 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blöthe M, Roden EE. 2009. Microbial iron redox cycling in a circumneutral pH groundwater seep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:468–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruun AM, Finster K, Gunnlaugsson HP, Nornberg P, Friedrich MW. 2010. A comprehensive investigation on iron cycling in a freshwater seep including microscopy, cultivation and molecular community analysis. Geomicrobiol. J. 27:15–34 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlé W. 1975. Die Mineral- und Thermalwässer von Mitteleuropa. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatellier X, Fortin D, West MM, Leppard GG, Ferris FG. 2001. Effect of the presence of bacterial surfaces during the synthesis of Fe oxides by oxidation of ferrous ions. Eur. J. Mineral. 13:705–714 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatellier X, et al. 2004. Characterization of iron-oxides formed by oxidation of ferrous ions in the presence of various bacterial species and inorganic ligands. Geomicrobiol. J. 21:99–112 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cochran WG. 1950. Estimation of bacterial densities by means of the “most probable number.” Biometrics 6:105–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornell RM, Schwertmann U. 2003. The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses, 2nd ed VCH, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reference deleted.

- 12. Druschel GK, Emerson D, Sutka R, Suchecki P, Luther GW. 2008. Low oxygen and chemical kinetic constraints on the geochemical niche of neutrophilic iron(II) oxidizing microorganisms. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72:3358–3370 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duckworth OW, Holmstrom SJM, Pena J, Sposito G. 2009. Biogeochemistry of iron oxidation in a circumneutral freshwater habitat. Chem. Geol. 260:149–158 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eaton AD, Clesceri LS, Rice EW, Greenberg AE. 2005. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association, Water Environment Federation, and American Water Works Association, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emerson D, Fleming EJ, McBeth JM. 2010. Iron-oxidizing bacteria: an environmental and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:561–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Emerson D, Moyer C. 1997. Isolation and characterization of novel iron-oxidizing bacteria that grow at circumneutral pH. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4784–4792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finneran KT, Housewright ME, Lovley DR. 2002. Multiple influences of nitrate on uranium solubility during bioremediation of uranium-contaminated subsurface sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 4:510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fortin D. 2004. What biogenic minerals tell us. Science 303:1618–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fortin D, Langley S. 2005. Formation and occurrence of biogenic iron-rich minerals. Earth Sci. Rev. 72:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fredrickson JK, et al. 2008. Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:592–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frei R, Gaucher C, Poulton SW, Canfield DE. 2009. Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes. Nature 461:250–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gault AG, et al. 2011. Microbial and geochemical features suggest iron redox cycling within bacteriogenic iron oxide-rich sediments. Chem. Geol. 281:41–51 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green SJ, Leigh MB, Neufeld JD. 2009. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) for microbial community analysis, p 4137–4158 In Timmis KN. (ed), Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grotzinger JP, Kasting JF. 1993. New constraints on Precambrian ocean composition. J. Geol. 101:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanert H. 2006. The genus Gallionella, p 996–997 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes, vol 7 Proteobacteria: delta, epsilon subclass. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hegler F, Posth N, Jiang J, Kappler A. 2008. Physiology of phototrophic iron(II)-oxidizing bacteria—implications for modern and ancient environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:250–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hong SH, Bunge J, Jeon SO, Epstein SS. 2006. Predicting microbial species richness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:117–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. James RE, Ferris FG. 2004. Evidence for microbial-mediated iron oxidation at a neutrophilic groundwater spring. Chem. Geol. 212:301–311 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang J, Kappler A. 2008. Kinetics of microbial and chemical reduction of humic substances: implications for electron shuttling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:3563–3569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson KW, et al. 2011. Increased abundance of Gallionella spp., Leptothrix spp. and total bacteria in response to enhanced Mn and Fe concentrations in a disturbed southern Appalachian high elevation wetland. Geomicrobiol. J. 29:124–138 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kappler A, Schink B, Newman DK. 2005. Fe(III) mineral formation and cell encrustation by the nitrate-dependent Fe(II)-oxidizer strain BoFeN 1. Geobiology 3:235–245 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klee AJ. 1993. A computer program for the determination of most probable number and its confidence limits. J. Microbiol. Methods 18:91–98 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langley S, et al. 2009. Preliminary characterization and biological reduction of putative biogenic iron oxides (BIOS) from the Tonga-Kermadec Arc, southwest Pacific Ocean. Geobiology 7:35–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ley RE, et al. 2006. Unexpected diversity and complexity of the Guerrero Negro hypersaline microbial mat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3685–3695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lovley DR. 1991. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 55:259–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lovley DR. 1997. Microbial Fe(III) reduction in subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:305–313 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ludwig W, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mikutta C, Kretzschmar R. 2008. Synthetic coprecipitates of exopolysaccharides and ferrihydrite. Part II. Siderophore-promoted dissolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72:1128–1142 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miot J, et al. 2009. Iron biomineralization by neutrophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73:696–711 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Müller HE, Brenner DJ, Fanning GR, Grimont PAD, Kämpfer P. 1996. Emended description of Buttiauxella agrestis with recognition of six new species of Buttiauxella and two new species of Kluyvera: Buttiauxella ferragutiae sp. nov., Buttiauxella gaviniae sp. nov., Buttiauxella brennerae sp. nov., Buttiauxella izardii sp. nov., Buttiauxella noackiae sp. nov., Buttiauxella warmboldiae sp. nov., Kluyvera cochleae sp. nov., and Kluyvera georgiana sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:50–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muyzer G, Teske A, Wirsen CO, Jannasch HW. 1995. Phylogenetic-relationships of Thiomicrospira species and their identification in deep-sea hydrothermal vent samples by denaturing gradient gel-electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Arch. Microbiol. 164:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nadkarni MA, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N. 2002. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology 148:257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nealson K, Scott J. 2006. Ecophysiology of the genus Shewanella, p 1133–1151 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes, vol 6 Proteobacteria: gamma subclass. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pierson BK, Parenteau MN, Griffin BM. 1999. Phototrophs in high-iron-concentration microbial mats: physiological ecology of phototrophs in an iron-depositing hot spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5474–5483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pierson BK, Parenteau MT. 2000. Phototrophs in high iron microbial mats: microstructure of mats in iron-depositing hot springs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:181–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Popoff M, Veron M. 1976. A taxonomic study of the Aeromonas hydrophila-Aeromonas punctata group. J. Gen. Microbiol. 94:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pruesse E, et al. 2007. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7188–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ratering S, Schnell S. 2001. Nitrate-dependent iron(II) oxidation in paddy soil. Environ. Microbiol. 3:100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Raven KP, Jain A, Loeppert RH. 1998. Arsenite and arsenate adsorption on ferrihydrite: kinetics, equilibrium, and adsorption envelopes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32:344–349 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rentz JA, Kraiya C, Luther GW, Emerson D. 2007. Control of ferrous iron oxidation within circumneutral microbial iron mats by cellular activity and autocatalysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:6084–6089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roden EE, et al. 2012. The microbial ferrous wheel in a neutral pH groundwater seep. Front. Microbiol. 3:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roden EE, Sobolev D, Glazer B, Luther GW. 2004. Potential for microscale bacterial Fe redox cycling at the aerobic-anaerobic interface. Geomicrobiol. J. 21:379–391 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schaedler S, et al. 2009. Formation of cell-iron-mineral aggregates by phototrophic and nitrate reducing anaerobic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 26:93–103 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schloss PD, et al. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schmidt C, Behrens S, Kappler A. 2010. Ecosystem functioning from a geomicrobiological perspective—a conceptual framework for biogeochemical iron cycling. Environ. Chem. 7:399–405 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schotterer U, et al. 1987. Isotopic geochemistry of the Engadine mineral springs of Scuol-Tarasp, Switzerland, p 277–286 In Isotope techniques in water resources development. IAEA, Vienna, Austria [Google Scholar]

- 57. Straub KL, Benz M, Schink B, Widdel F. 1996. Anaerobic, nitrate-dependent microbial oxidation of ferrous iron. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1458–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Straub KL, Hanzlik M, Buchholz-Cleven BE. 1998. The use of biologically produced ferrihydrite for the isolation of novel iron-reducing bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:442–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Straub KL, Schonhuber WA, Buchholz-Cleven BEE, Schink B. 2004. Diversity of ferrous iron-oxidizing, nitrate-reducing bacteria and their involvement in oxygen-independent iron cycling. Geomicrobiol. J. 21:371–378 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stumm W, Morgan JJ. 1995. Aquatic chemistry: chemical equilibria and rates in natural waters, 3rd ed John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suda S, et al. 2002. Taxonomic revision of water-bloom-forming species of oscillatorioid cyanobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1577–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sung W, Morgan JJ. 1980. Kinetics and product of ferrous iron oxygenation in aqueous systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 14:561–568 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Trouwborst RE, Johnston A, Koch G, Luther GW, III, Pierson BK. 2007. Biogeochemistry of Fe(II) oxidation in a photosynthetic microbial mat: implications for Precambrian Fe(II) oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71:4629–4643 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tschech A, Pfennig N. 1984. Growth yield increase linked to caffeate reduction in Acetobacterium woodii. Arch. Microbiol. 137:163–167 [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wagner C, Mau M, Schlömann M, Heinicke J, Koch U. 2007. Characterization of the bacterial flora in mineral waters in upstreaming fluids of deep igneous rock aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 112(G1):G01003 doi:10.1029/2005JG000105 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Weber KA, Urrutia MM, Churchill PF, Kukkadapu RK, Roden EE. 2006. Anaerobic redox cycling of iron by freshwater sediment microorganisms. Environ. Microbiol. 8:100–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wexsteen P, JaffÉ FC, Mazor E. 1988. Geochemistry of cold CO2-rich springs of the Scuol-Tarasp region, Lower Engadine, Swiss Alps. J. Hydrogeol. 104:77–92 [Google Scholar]

- 68. Widdel F. 1980. Anaerober Abbau von Fettsäuren und Benzoesäure durch neu isolierte Arten. Ph.D. dissertation Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 69. Widdel F, Pfennig N. 1981. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. I. Isolation of a new sulfate-reducer enriched with acetate from saline environments. Description of Desulfobacter postgatei gen. nov. sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 129:395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Widdel F, et al. 1993. Ferrous iron oxidation by anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Nature 362:834–836 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou J, Bruns MA, Tiedje JM. 1996. DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:316–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.