Abstract

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in macaques is so far the best animal model for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) studies, but suppressing viral replication in infected animals remains challenging. Using a novel single-round infectivity assay, we quantitated the antiviral activities of antiretroviral drugs against SIV. Our results emphasize the importance of the dose-response curve slope in determining the inhibitory potential of antiretroviral drugs and provide useful information for regimen selection in treating SIV-infected animals in models of therapy and virus eradication.

TEXT

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly reduced the morbidity and mortality of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (17, 18, 29), but eradication is still an unrealistic goal due to a low level of viral persistence in treated subjects (30). When treatment is interrupted, a rapid rebound of viremia can be observed in most infected individuals (9, 15, 19). A major barrier to eradication is the extremely stable reservoir of latent virus in resting memory CD4+ T cells (7, 8, 14, 33, 38). As a result, lifelong treatment is required to suppress viral replication and prevent disease progression to AIDS. In the meantime, drug resistance and rebound viremia can develop under suboptimal treatment conditions (10, 25, 37). Therefore, quantitation of the antiviral activity of antiretroviral drugs and drug regimens is important and could help to choose regimens that produce the maximum level of suppression. Using a novel single-round infectivity assay with high sensitivity, Shen et al. showed that the dose-response curve slope was a neglected yet crucial dimension in measurement of antiviral activity (32). Slope values are class specific for anti-HIV-1 drugs and define intrinsic limitations on antiviral activity for different classes (23, 32).

Infection of macaques with some forms of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) causes a disease that closely resembles HIV-1 infection in humans, making the SIV-macaque system the best animal model to study HIV-1 pathogenesis and potential intervention strategies (2, 3, 11, 20, 24, 31, 36). Treatment studies in SIV-infected animals have yielded valuable insights for antiretroviral therapy (1, 3, 16, 27, 28). Currently, there is a great need for an animal model of HAART in which virus eradication strategies can be explored. Achieving suppression of SIV replication to an extent comparable to that seen in HIV-1-infected humans on HAART is the critical first step in the development of models for viral eradication strategies (12, 26). However, it is still not clear what regimen is optimal for suppressing SIV replication in vivo. A quantitative study of the antiviral activities of current antiretroviral drugs against SIV infection could guide regimen selection to maximize inhibitory potential. It is particularly important to determine whether the dose-response curve slope is a critical determinant of activity against SIV, as it is in activity against HIV-1 (23, 32).

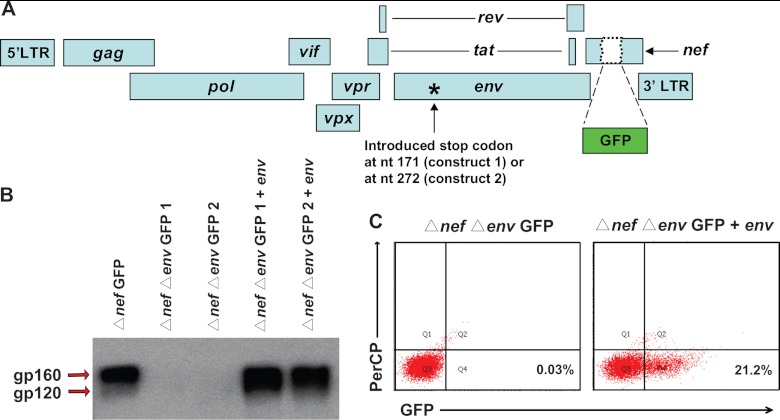

To measure the antiviral activities of current antiretroviral drugs against SIV, we developed a single-round infectivity assay for SIV with wide dynamic range and high sensitivity (Fig. 1A). The proviral backbone used for the assay was modified from SIV/17E-Fr Δnef GFP (22). Nucleotides 171 or 272 of env were mutated (QuickChange II; Agilent Technologies) separately to introduce stop codons to prevent endogenous env expression (Δnef Δenv GFP 1 and 2), resulting in viruses capable of only single-round infection (Fig. 1A). The env gene from SIVmac239 was cloned into the previously described pGAG expression vector (4) to replace gag. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) posttranscriptional regulatory element (PRE) contained in this vector enables high-level, Rev-independent expression of SIV Env. Western blot analysis (polyclonal antibody to SIV gp120/160; Abcam) showed no Env (gp160 and gp120) production by cells transfected with the Δnef Δenv GFP 1 or Δnef Δenv GFP 2 constructs alone, whereas cotransfection of these proviral constructs and the env expression vector yielded Env as expected (Fig. 1B). Pseudoviruses were generated by cotransfecting 293T cells with Δnef Δenv GFP 1 and the Env expression vector. Infections were carried out in primary CD4+ T cells from healthy rhesus macaques. Because activated CD4+ T cells are the principal target cells for HIV-1 and SIV in vivo, macaque cells were stimulated with 5 μg/ml concanavalin A and 100 U/ml interleukin-2 (IL-2) as described by Zhang et al. (39). Thus, the analysis presented here reflects inhibitory effects in activated CD4+ T cells, and it is important to note that there may be quantitative differences in the effects in other cell types. After 72 h of stimulation, CD4+ T cells were isolated using the Miltenyi CD4+ T cell isolation kit for nonhuman primates according to the manufacturer's instructions. The macaque CD4+ T cells were then infected and cultured using our previously described procedure for human CD4+ T cells (32). For infection of every 1 million primary CD4+ T lymphoblasts, we used a 100-ng p27 input of prestandardized (by p27 ELISA; Zeptometrix) pseudotyped SIV. This amount of input virus is in the linear range of infectivity curves and below virus concentrations at which the level of infection reaches a plateau. The input gives about 20% infection (Fig. 1C). Because flow cytometric analysis allows detection of individual infection events, a 20% infection level still leaves a very wide dynamic range to assess inhibition of infection by antiretroviral drugs (32). No infection was detected when pseudoviruses generated without the Env expression vector were used, indicating that env expression in trans was required for infectivity. Thus, the pseudoviruses are only capable of a single round of infection. We chose a single-round infectivity assay over multiround assays to avoid complexities introduced by the growth and death of target cells and viral growth and evolution over time. Previous studies have shown that single-round assays more directly reflect the degree of inhibition by antiretroviral drugs (13, 23, 32).

Fig 1.

A single-round SIV infectivity assay for quantitation of antiviral activity in vitro. (A) Proviral construct used to generate pseudotyped SIV for infections. The GFP coding sequence was inserted into the nef gene. Stop codons were introduced into the N-terminal region of the env gene (at nucleotide position 171 or 272), to render the viruses capable of only a single round of infection. (B) Detection of gp160 and gp120 in concentrated virions by Western blot analysis. The indicated proviral constructs were transfected alone or with an env expression plasmid into HEK293T cells. Concentrated virion preparations were made by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant from transfected cells. The envelope protein (gp160/gp120) was detected by blotting with a polyclonal antibody (Abcam). (C) Expression of GFP by infected CD4+ T cells. Concentrated virions were used to infect primary rhesus macaque CD4+ T cells. Representative dot plots of GFP expression are shown for virions made by transfecting a proviral construct alone (left) or together with an env expression plasmid (right). PerCP, peridinin chlorophyll protein.

Antiretroviral drugs were acquired from Merck and the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, NIH, and were prepared as previously described (32). Single-round infectivity assays were carried out as previously described (32). Dose-response curves were obtained by normalizing the percentage of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells without drug treatment to 100% (Fig. 2C). Inhibition data were analyzed using the median effect model (5, 6), which provides a rigorous description of dose-response relationships (equations 1 and 2), as follows:

| (1) |

or,

| (2) |

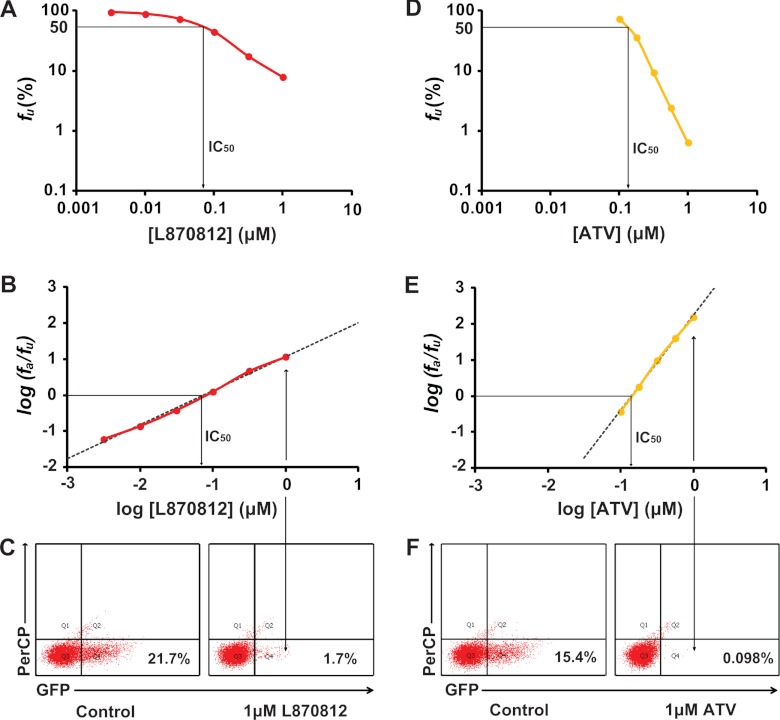

Fig 2.

Measurement of IC50 and m using single-round infectivity assay. (A) Log-log dose-response curve for the integrase inhibitor L870812. Each point represents the mean from more than three experiments. The IC50 of L870812 is shown by the arrow. (B) Linearized dose-response curve for L870812 based on median effect model. The IC50 of L870812 is shown by the arrow. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots showing detection of cells that were infected in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 1 μM L870812. (D) Log-log dose-response curve for the protease inhibitor ATV. Each point represents the mean from more than three experiments. The IC50 of ATV is shown by the arrow. (E) Linearized dose-response curve for ATV based on median effect model. The IC50 of ATV is shown by the arrow. (F) Representative flow cytometry plots showing detection of cells that were infected with virions generated in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 1 μM ATV.

For inhibition of SIV infection, fa is the fraction of infection events affected by the drug and fu is the fraction of events unaffected by the drug (fa + fu = 1). D is the drug concentration, IC50 is the drug concentration that causes 50% of the maximum inhibitory effect, and m is the slope of the dose-response curve. The slope parameter is analogous to the Hill coefficient (21) and reflects cooperativity, typically in the case of multiple ligands binding to a multivalent site. By fitting data to the median effect model (equation 1) using least-square regression analysis, we obtained the IC50 and the slope (m value) from each dose-response curve (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). At high concentrations of the integrase inhibitors raltegravir and L870812, a low level of GFP expression in a small fraction of cells with unintegrated virus is evident. This effect was corrected as described previously (32).

IC50 is the most widely used measure of drug potency, but the clinical concentrations of HIV-1 drugs are usually much higher than the IC50s. This is also the case for treating SIV-infected macaques. Under such conditions, the shape of the dose-response curve (slope) must be considered in evaluating drug activity. The importance of the dose-response curve slope in determining drug activity is illustrated in Fig. 2. In this experiment, the integrase inhibitor L870812 has a lower IC50 than the protease inhibitor atazanavir (ATV) (Fig. 2B and E), suggesting that L870812 is a more potent inhibitor. However, at concentrations approximately 10-fold higher than the IC50 of L870812 (1 μM), the fraction of infection events unaffected by the drug was much higher for L870812 than for ATV (Fig. 2), indicating that ATV is actually the better inhibitor in the treatment-relevant concentration range, as a result of the steeper slope of its dose-response curve (Fig. 2). This observation further emphasizes the fact that the dose-response curve slope is a neglected but critical dimension in the measurement of antiviral activity.

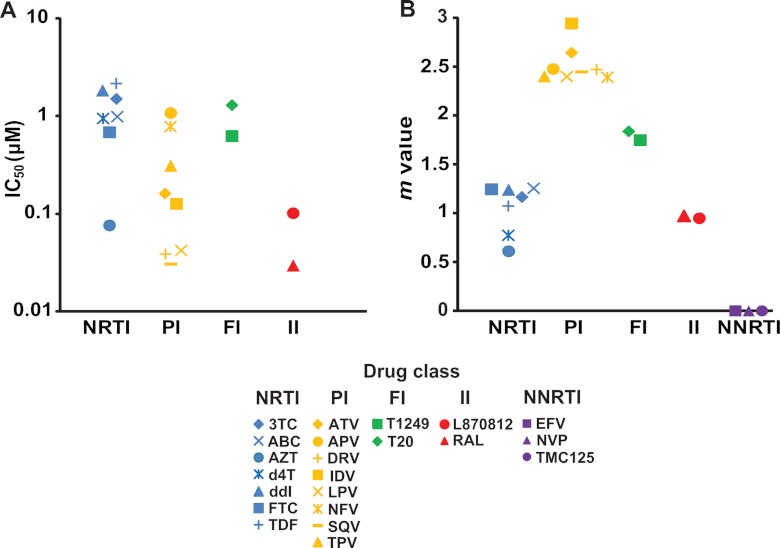

The IC50s calculated from each dose-response curve are shown in Fig. 3A. The IC50s for the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and fusion inhibitors (FIs) are generally in the low μM range, except for azidothymidine (AZT), which has an IC50 below 0.1 μM (Fig. 3A). The IC50s of integrase inhibitors (IIs) are lower (Fig. 3A). The IC50s of protease inhibitors (PIs) vary widely (Fig. 3A). Not surprisingly, the IC50s obtained for a given drug against SIV were higher than those observed for the same drug against HIV-1 (32). As discussed above, the slopes of dose-response curves must also be considered. As previously reported for HIV-1 infection in humans (23, 32), each drug class showed a characteristic slope value for inhibition of SIV infection (Fig. 3B). The NRTIs and IIs all showed slopes close to 1 (Fig. 3B). The slopes of the FIs were ∼1.8 (Fig. 3B). The PIs all showed slopes greater than 2, with a range from 2.4 to 2.9 (Fig. 3B). Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) did not inhibit SIV infection, and the slopes are shown as zero (Fig. 3B). These results strongly support the conclusions of studies in the HIV-1 system (23, 32) which indicate that the dose-response curve slope strongly influences the intrinsic activity of antiretroviral drugs in suppressing viral replication, regardless of the retrovirus targeted.

Fig 3.

IC50 and m values of anti-HIV-1 drugs against SIV infection in vitro. (A) The IC50s of anti-HIV drugs from different classes. Values for the NNRTIs were all greater than 100 μM, the highest concentration tested, and are not shown. (B) m values for antiretroviral drugs from different classes. Definitions for drug name abbreviations are as follows: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; ddI, didanosine; FTC, emtricitabine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; ATV, atazanavir; APV, amprenavir; DRV, darunavir; IDV, indinavir; LPV, lopinavir; NFV, nelfinavir; SQV, saquinavir; TPV, tipranavir; T20, enfuvirtide; RAL, raltegravir; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; TMC125, etravirine.

To better evaluate the antiviral activities of anti-HIV-1 drugs, we previously developed a new index termed instantaneous inhibitory potential (IIP), which takes into account all three parameters in the median effect equation (IC50, drug concentration, and slope) (32). IIP is equal to log(1/fu) and can be thought of as the number of logs by which single-round infection events are reduced at clinically relevant drug concentrations. IIP can be calculated from equation 3, as follows:

| (3) |

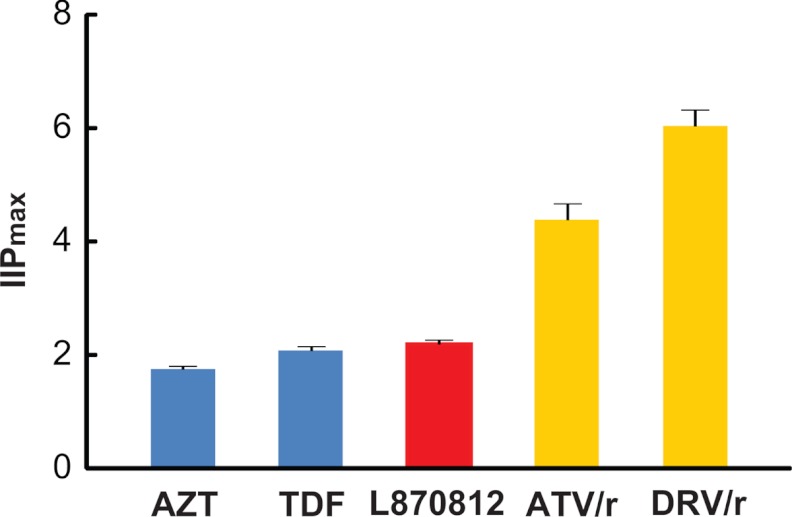

Here, D is the plasma drug concentration achieved with standard dosing. D varies over time due to drug metabolism in vivo. We calculated IIP values for five representative drugs for which information on plasma drug concentration in treated rhesus macaques was available (34, 35; our unpublished data). Peak plasma concentrations were used to calculate IIP, so the values are shown as IIPmax (Fig. 4). Among these five drugs, darunavir with ritonavir boosting (DRV/r) had the highest IIP (∼6), meaning that DRV/r reduced the single-round infectivity of SIV by up to 6 logs at expected plasma concentrations. This value is high enough so that DRV/r monotherapy might be able to reduce viremia to undetected levels in infected rhesus macaques. ATV/r has an IIPmax value close to 4.4 (Fig. 4), much higher than azidothymidine (AZT), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), or L870812 has (close to 2), suggesting that drugs from NRTI or II classes may not have activities as high as those of PIs when used to treat SIV infection in rhesus macaques. For most drugs, the maximal tolerated dose has not been established in the SIV system. However, when this dosing is established, the plasma drug concentrations can be combined with the IC50 and m values presented here and used to compute IIP with equation 3. With more extensive pharmacokinetic data, it will also be possible to compute average IIP values over the whole dosing interval. In humans, these values show the same patterns of drug class variation as IIPmax values (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). IC50 and m values for inhibition of HIV-1 are shown for purposes of comparison in Table S3 in the supplemental material. We have recently described a method that allows prediction of the combined effects of multiple antiretroviral drugs based on the pharmacodynamics parameters (IC50 and m) of individual drugs (23), and therefore, it should also be possible to predict combined effects in the macaque system.

Fig 4.

Estimated IIPmax values ± standard deviations for five representative drugs against SIV infection in rhesus macaques. The values were calculated using equation 3. Here D is the maximum concentration of the drug in plasma at the doses used to treat experimental SIV infection.

In conclusion, this study provides a quantitative measurement of the antiviral activities of antiretroviral drugs against SIV infection. Our results demonstrate with a distinct virus the importance of the dose-response curve slope in determining antiviral activity. The dose-response curve slope strongly influences class-specific inhibitory potential against SIV infection. The IIP index takes the drug concentration, IC50, and dose-response curve slope into consideration, therefore making it a more accurate way to evaluate drug efficacy. We believe this study may facilitate the selection of regimens that can maximally suppress SIV replication in vivo for use in models of antiretroviral therapy and viral eradication.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brandon Bullock, Lucio Gama, and Suzanne Queen for assistance with animal bleeding and isolating rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells. We thank Lin Shen for helpful discussions about the experiments. We thank the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program of NIH and Merck for providing anti-HIV-1 drugs.

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, by NIH grants 5R01AI081600 and 5P01MH070306 and the Martin Delaney CARE Collaboratory, and by the Foundation for AIDS Research (amFAR).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambrose Z, et al. 2007. Suppression of viremia and evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance in a macaque model for antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 81:12145–12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barouch DH, et al. 2002. Eventual AIDS vaccine failure in a rhesus monkey by viral escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 415:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyer JD, et al. 2006. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy during chronic SIV infection leads to rapid reduction in viral loads and the level of T-cell immune response. J. Med. Primatol. 35:202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buck CB, et al. 2001. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene encodes an internal ribosome entry site. J. Virol. 75:181–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chou TC. 1976. Derivation and properties of Michaelis-Menten type and Hill type equations for reference ligands. J. Theor. Biol. 59:253–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chou TC, Talalay P. 1984. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 22:27–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chun TW, et al. 1997. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 387:183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chun TW, et al. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:13193–13197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chun TW, Davey RT, Jr, Engel D, Lane HC, Fauci AS. 1999. Re-emergence of HIV after stopping therapy. Nature 401:874–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clavel F, Hance AJ. 2004. HIV drug resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:1023–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniel MD, et al. 1985. Isolation of T-cell tropic HTLV-III-like retrovirus from macaques. Science 228:1201–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dinoso JB, et al. 2009. A simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaque model to study viral reservoirs that persist during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 83:9247–9257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Domaoal RA, et al. 2008. Pre-steady-state kinetic studies establish entecavir 5′-triphosphate as a substrate for HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 283:5452–5459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finzi D, et al. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia F, et al. 1999. Dynamics of viral load rebound and immunological changes after stopping effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 13:F79–F86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. George MD, Reay E, Sankaran S, Dandekar S. 2005. Early antiretroviral therapy for simian immunodeficiency virus infection leads to mucosal CD4+ T-cell restoration and enhanced gene expression regulating mucosal repair and regeneration. J. Virol. 79:2709–2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gulick RM, et al. 1997. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:734–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hammer SM, et al. 1997. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:725–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harrigan PR, Whaley M, Montaner JS. 1999. Rate of HIV-1 RNA rebound upon stopping antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 13:F59–F62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hel Z, et al. 2000. Viremia control following antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic immunization during primary SIV251 infection of macaques. Nat. Med. 6:1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill AV. 1910. The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J. Physiol. 40:iv-vii [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwata N, et al. 2007. Simian fetal brain progenitor cells for studying viral neuropathogenesis. J. Neurovirol. 13:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jilek BL, et al. 2012. A quantitative basis for antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 18:446–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lackner AA, Veazey RS. 2007. Current concepts in AIDS pathogenesis: insights from the SIV/macaque model. Annu. Rev. Med. 58:461–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larder BA, Darby G, Richman DD. 1989. HIV with reduced sensitivity to zidovudine (AZT) isolated during prolonged therapy. Science 243:1731–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewis MG, et al. 2011. Gold drug auranofin restricts the viral reservoir in the monkey AIDS model and induces containment of viral load following ART suspension. AIDS 25:1347–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. North TW, et al. 2005. Suppression of virus load by highly active antiretroviral therapy in rhesus macaques infected with a recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus containing reverse transcriptase from human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 79:7349–7354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. North TW, et al. 2010. Viral sanctuaries during highly active antiretroviral therapy in a nonhuman primate model for AIDS. J. Virol. 84:2913–2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perelson AS, et al. 1997. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 387:188–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pierson T, McArthur J, Siliciano RF. 2000. Reservoirs for HIV-1: mechanisms for viral persistence in the presence of antiviral immune responses and antiretroviral therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:665–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shen A, et al. 2003. Resting CD4+ T lymphocytes but not thymocytes provide a latent viral reservoir in a simian immunodeficiency virus-Macaca nemestrina model of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 77:4938–4949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen L, et al. 2008. Dose-response curve slope sets class-specific limits on inhibitory potential of anti-HIV drugs. Nat. Med. 14:762–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siliciano JD, et al. 2003. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 9:727–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Rompay KK, et al. 1995. Immediate zidovudine treatment protects simian immunodeficiency virus-infected newborn macaques against rapid onset of AIDS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:125–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Rompay KK, et al. 2004. Biological effects of short-term or prolonged administration of 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine (tenofovir) to newborn and infant rhesus macaques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1469–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Veazey RS, et al. 2003. Use of a small molecule CCR5 inhibitor in macaques to treat simian immunodeficiency virus infection or prevent simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 198:1551–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wei X, et al. 1995. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature 373:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wong JK, et al. 1997. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278:1291–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang D, et al. 2003. Optimization of ex vivo activation and expansion of macaque primary CD4-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells for use in anti-HIV immunotherapy and gene therapy strategies. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 32:245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.