Abstract

While epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has been shown to be important in the entry process for multiple viruses, including hepatitis C virus (HCV), the molecular mechanisms by which EGFR facilitates HCV entry are not well understood. Using the infectious cell culture HCV model (HCVcc), we demonstrate that the binding of HCVcc particles to human hepatocyte cells induces EGFR activation that is dependent on interactions between HCV and CD81 but not claudin 1. EGFR activation can also be induced by antibody mediated cross-linking of CD81. In addition, EGFR ligands that enhance the kinetics of HCV entry induce EGFR internalization and colocalization with CD81. While EGFR kinase inhibitors inhibit HCV infection primarily by preventing EGFR endocytosis, antibodies that block EGFR ligand binding or inhibitors of EGFR downstream signaling have no effect on HCV entry. These data demonstrate that EGFR internalization is critical for HCV entry and identify a hitherto-unknown association between CD81 and EGFR.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), a member of the Flaviviridae family of viruses, is a major cause of chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2). While the generation of the HCV pseudoparticle (HCVpp) and infectious cell culture (HCVcc) models have resulted in a significant increase in our understanding of HCV entry, the molecular mechanisms involved in viral internalization and fusion still remain unclear. HCV entry occurs through the coordinated interactions between the E1-E2 HCV glycoproteins and at least four essential cellular entry factors: CD81 (42), scavenger receptor B type I (SR-BI) (47), occludin (OCLN) (43), and claudin 1 (CLDN1) (11). The E2 glycoprotein has been demonstrated to bind CD81 (42) and SR-BI (47), and antibodies that bind to highly conserved residues 412 to 423 on the E2 glycoprotein possess broad neutralization capabilities against multiple HCV genotypes by inhibiting HCV-CD81 interactions (40). Although HCV is known to enter hepatocytes via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (1), the host-virus interactions that govern HCV internalization are not well understood. Only one of the HCV entry factors, SR-BI, enhances HCV entry by mediating the selective uptake of cholesterol esters from HDL (8). Although HCV was recently demonstrated to induce CD81 and CLDN1 endocytosis (14), the molecular interactions important for HCV internalization still remain unclear.

Multiple RNA and DNA viruses have evolved to induce a variety of receptor-mediated signaling events that are critical for different aspects of viral entry (7, 12, 16, 53). HCV regulates multiple intracellular signaling pathways, some of which been implicated in the progression of HCV-related HCC (23, 53). HCV interaction with CD81 has been demonstrated to activate multiple downstream signaling pathways, including Rho GTPase family members, Cdc42, mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, and members of the ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) family of proteins (3, 6, 13). In addition, CD81 binding by HCV primes the E1-E2 heterodimer complex for low pH-dependent fusion events early in the HCV entry process (49). All of these data suggest that HCV activates multiple intracellular signaling events and that CD81, in particular, may be important in both early and late stages of the viral entry process.

Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has been demonstrated to be critical for entry of a number of viruses, including HCV, influenza A virus, and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (5, 9, 28). EGFR, a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, is highly expressed in the liver and is upregulated in many cancers (27, 32). Ligand binding to EGFR activates a vast array of intracellular signaling events that are critical for cell division, death and motility (56). Lupberger et al. has recently identified EGFR as a cofactor for HCV entry (28), and while the authors demonstrate that EGFR ligands can increase HCV infectivity in vitro, the actual molecular mechanisms still remain unclear. In this report, we demonstrate that binding of HCVcc particles to hepatocytes or antibody-mediated cross-linking of CD81 induces EGFR activation and that this activation is required for HCV endocytosis. We also demonstrate that EGFR ligands (EGF or transforming growth factor α [TGF-α]) enhance the kinetics of HCV entry by inducing the endocytosis of EGFR-CD81 complexes. Furthermore, our data suggest that EGFR internalization is critical for HCV entry since we can experimentally bypass the requirement for kinase activation by using EGFR antibodies that block both ligand- and HCV-induced EGFR activation and yet induce EGFR internalization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and small molecule inhibitors.

Antibodies used in the present study were obtained from commercial sources unless stated otherwise: mouse anti-human EGFR (MBL, Naka-ku Nagoga, Japan); anti-phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), anti-EGFR (conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555), anti-EGFR (conjugated with magnetic bead), and anti-actin horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); anti-CD81 (JS-81, unconjugated and fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] conjugated) and anti-EEA1 FITC conjugated (BD Pharmingen, Dan Diego, CA); anti-CD81 (B11; Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); anti-occludin (1G7) and anti-SR-B1 (Novus Biol LLC, Littleton, CO); anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN); and anti-EGFR clone LA1 (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Anti-CLDN1 antibody clone 5.16v5, anti-CMV, and anti-EGFR (clone D1.5 and cetuximab) antibodies were expressed and purified at Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). The anti-CLDN1 neutralizing antibody clone 5.16v5 was identified and generated as previously described (17). Anti-E2 (AP33) antibody was obtained under license from MRC Technology (United Kingdom). All small molecules were purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ), except as follows: farnesyl thiosalicylic acid was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and erlotinib, lapatinib, Gleevec, and the HCV protease (danoprevir) inhibitors were chemically synthesized.

Tissue culture and generation of full-length infectious HCVcc cDNAs.

Huh-7.5 cells were obtained under license from Apath LLC (St. Louis, MO) and cultured in complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (cDMEM; supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 mg of streptomycin/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids) (17, 20, 21, 58). Cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes (PHH) were purchased either from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) or SciKon Innovation (Chapel Hill, NC) and cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Jc1 (J6/C3; genotype 2a) and Jc1-Rluc HCVcc cDNAs were generated as previously described (17, 19). The bicistronic neomycin resistance gene expressing genotype 1b chimeric genome (Con1/C3-neo HCVcc) was chemically synthesized according to sequences from the PubMed database (genotype 1b Con1; GenBank accession no. AJ238799) and the chimeric strategy published previously (41) and cloned into pUC19 plasmid (pUC Con1/C3-neo).

Generation of HCVcc and herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) stocks.

Jc1 virus stocks were generated by transfecting Huh-7.5 cells with in vitro transcribed full-length HCV RNA as described previously (20, 21, 58). Plasmids were linearized with XbaI, and in vitro-transcribed RNA was generated using Megascript kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCV RNA was transfected into Huh-7.5 cells by electroporation as described previously (20, 21, 58). Supernatants from Jc1 RNA-transfected cells were harvested starting from 3 days posttransfection, titrated, and pooled to generate laboratory stocks. HCVcc titers were measured using the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) calculator as described previously (25). For Con1/C3-neo HCVcc, Huh-7.5 cells were transfected with in vitro-transcribed Con1/C3-neo RNA as described above. At 5 days posttransfection, the culture medium was replaced with medium containing 350 μg of Geneticin/ml, and the cells were passaged for 22 days under selection until cell culture-adapted clones emerged. Individual clones were amplified, and supernatants were collected, divided into aliquots, and stored at −70°C. To obtain high-titer Jc1 HCVcc stocks, supernatants from virally infected Huh-7.5 cells were concentrated using 100,000-molecular-weight (MW) cutoff Vivaspin concentrators (Vivaproducts, Inc., Littleton, MA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Control concentrated medium was generated in parallel using culture supernatants from naive Huh-7.5 cells. HSV-1 stocks were generated as described previously (50).

Generation of HCVpp stocks.

HCV pseudoparticle (HCVpp) stocks were generated as previously described (17), with some exceptions. To generate the H77, Con1 and J6CF HCVpp HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with the Delta 8.9 plasmid containing HIV-1 gag-pol (44), the CMV-Luc-DsRed lentiviral transfer construct (17), and a plasmid expressing respective HCV E1E2 cDNA using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 48 h posttransfection, the medium containing HCVpp was collected, clarified, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size membranes, and used for infection of Huh-7.5 cells. For J6CF HCVpp, the supernatants were concentrated using 100,000-MW cutoff Vivaspin concentrators as discussed above. Viruses were titrated based on luciferase readings to normalize the multiplicity of infection (MOI) for all HCVpp stocks.

Virus infection assays.

HCVpp and HCVcc neutralization assays were performed as described previously (17). MOIs for Jc1 HCVcc infections were calculated based on virus titer, as measured by TCID50 calculations (25). Neutralization assays using HCVpp or HCVcc viruses were performed in 96-well plates (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY). Briefly, 5 × 103 Huh-7.5 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate 16 h prior to neutralization assay. The following day, 3-fold dilutions of inhibitors were incubated with naive Huh-7.5 cells for 1 h at 37°C, followed by the addition of HCVcc or HCVpp at an MOI of 0.3 for an additional 4 h. Unbound virus was removed and cells were washed once with cDMEM and replaced with fresh medium. The cultures were maintained for 3 days before measuring HCV infection. HCVpp infection was determined using the Luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCVcc infection was determined by real-time quantitative PCR as described below. To determine effects on HCV replication and core production, Huh-7.5 cells were infected until 100% of cells were infected, as determined by immunofluorescence staining for the HCV core. HCVcc-infected cells were seeded into 96-well plates, treated with inhibitors, and assayed as described above. HCV core release from infected cells was determined using an Ortho HCV core enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (supplied by Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For studies of EGFR activation, HSV-1 was incubated with Huh-7.5 cells (MOI = 10) at 4°C for 1 h to allow binding, after which the cells were shifted to 37°C for another hour.

RNA extractions, reverse transcription, and RT-qPCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis (RT-qPCR) was performed as described previously (17, 20) with some changes. Total RNA was harvested using the SV 96 total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR was performed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit and TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), respectively. HCV infection was measured by real-time PCR to detect HCV and normalized to GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) levels using multiplex PCR. The probe sequence for HCV was 6-FAM-TATGAGTGTCGTACAGCCTC-MGBNFQ. The HCV primer sequences were 5′-CTTCACGCAGAAAGCGCCTA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAAGCGCCCTATCAGGCAGT-3′ (antisense). The probe sequence for human GAPDH was VIC-ATGACCCCTTCATTGACCTC-MGBNFQ, and the primer sequences were 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′ (antisense). The data were analyzed using relative expression (2−ΔΔCT method) normalized to GAPDH as described previously (21, 26).

siRNA transfections.

EGFR and CD81 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and Thermo Scientific (Lafayette, CO), respectively. A total of 2 × 105 Huh-7.5 cells were seeded into six-well plates. The following day, the cells were transfected with 100 pmol of nontargeting (NT), CD81-specific, or EGFR-specific siRNAs using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h, the transfected cells were incubated with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 10) at 4°C for 1 h, after which the cells were washed three times with DMEM and shifted to 37°C for another hour. EGFR activation was detected by Western blot analyses, as described below. At the 48-h time point, duplicate transfected wells were used for flow cytometry to detect cell surface expression of CD81, EGFR, and Her2, which is described in more detail below.

EGFR immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemical staining for EGFR was performed by an automated method on the Ventana Discovery XT system (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ) using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 4-μm sections. The sections were treated with protease I, incubated with anti-EGFR antibody (Ventana Confirm, clone 3C6), detected with Ventana's HRP-conjugated OmniMap anti-mouse antibody, and visualized with diaminobenzidine. Flow cytometry analyses for cell surface expression of EGFR, HER3, HER4, and CD81 on Huh-7.5 or PHH were performed as follows. Huh-7.5 cells were detached using cell dissociation buffer (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cryopreserved PHH cells were thawed and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% FBS. Then, 5 × 105 Huh-7.5 or PHH cells were incubated with 2.5 μg of primary antibody/ml for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with allophycocyanin-labeled secondary antibody (Jackson Research) at a 1:200 final dilution for 1 h at 4°C. The cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS. For flow cytometric analyses of Her2, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Her2 antibody (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was used at 20 μl per test. Cell acquisition was performed on a FACSAria (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed with Flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Acridine orange immunofluorescence microscopy.

Acridine orange staining was performed as previously described, with some modifications (55). Briefly, Huh-7.5 cells grown in chamber slides were left untreated or treated with 50 μM chlorpromazine or 250 nM bafilomycin A1 for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with 1 μg of acridine orange (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)/ml for 15 min, washed with ice-cold PBS three times, and mounted with a coverslip. Green (490-nm) and orange (570-nm) fluorescence images were visualized immediately using an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope.

Time-of-addition studies with erlotinib, EGFR ligands (TGF-α and EGF), and anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab, D1.5).

Huh-7.5 cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate. The following day, cells were incubated with Jc1-Rluc HCVcc at an MOI of 0.3 at 4°C for 1 h, after which the cells were washed three times with DMEM, shifted to 37°C, and treated with anti-CD81 (JS-81) antibody (10 μg/ml), anti-CLDN1 antibody (10 μg/ml), erlotinib (10 μM), or chlorpromazine (10 μM) at different times after the temperature shift (30, 60, 120, 135, 150, 165, 180, 210, and 240 min). After 4 h, the cells were washed and replaced with fresh culture medium for the remainder of the assay (72 h). For time-of-addition experiments with EGFR ligands, antibodies, or HDL, Huh-7.5 cells were treated with either 12.5 nM TGF-α (US Biologicals, Swampscott, MA), 16 nM EGF (Millipore), 20 μg of anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab or D1.5)/ml, or 10 μg of HDL (EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ)/ml for various times at 37°C (0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 240 min). The inoculum was washed after 4 h, and cultures were replaced with fresh medium. HCVcc infection was measured at 72 h using the Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega). Luciferase measurements were normalized to infections occurring in the absence of ligands or antibodies. To determine whether TGF-α affected the kinetics of HCVcc replication or polyprotein translation, Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1-Rluc (MOI = 0.3) for 4 h at 37°C to allow enter to occur, after which the cells were either left untreated or treated with TGF-α (12.5 nM). HCV replication was measured by luciferase assay at various time points (4, 16, 36, and 72 h) post-TGF-α treatment. For HSV-1 time-of-addition experiments, Huh-7.5 cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) and incubated with TGF-α (12.5 nM), HDL (10 μg/ml), or TGF-α+HDL for 20, 60, and 1,080 min (18 h), after which the cells were washed and replenished with fresh medium for the remainder of the assay. Maximal infection could be achieved after incubation of HSV-1 for 60 min. Infection was monitored at 18 h by flow cytometry staining for HSV-1 glycoprotein B (gB), as described previously (50).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analyses.

Huh-7.5 and PHH cell lysates were prepared by using ice-cold 1× cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The lysates were further disrupted by passing through a 26-gauge needle. Unbroken cell and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Equal protein levels of the prepared lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting to detect activated (phosphorylated) and total EGFR. For immunoprecipitation analyses, antibodies (15 μl of conjugated antibody-bead slurry or 10 μg of unconjugated antibodies) were added to cell lysates, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. For unconjugated antibodies, protein G-beads (Cell Signaling Technology) were added to the supernatant for an additional 3 h of incubation. The beads were washed using 1× cell lysis buffer, and Laemmli buffer was added. Western blotting analyses were performed using 1:1,000 or 1:2,000 dilutions for anti-phospho EGFR (Tyr-1068) or anti-total EGFR, respectively, according to manufacturer's recommendations (Cell Signaling Technology).

Indirect Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described with some modifications (20, 58). For all studies, 3 × 104 Huh-7.5 cells were seeded into 8-chamber coverglasses (Becton Dickinson). The next day, the cells were treated as described below. Unless stated otherwise, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed once with PBS, and incubated in blocking buffer (PBST containing 0.3% Triton X-100, 3% bovine serum albumin, and 10% FBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with 5 μg of primary antibody/ml overnight at 4°C, followed by three washes with PBS and incubation with secondary fluorescently labeled antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with PBS and mounted with SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Life Technologies) and analyzed using the Leica TCS SPE confocal microsystem. For analysis of the effect of TGF-α on expression and localization of EGFR and the HCV host receptors, cells were treated with 5 nM TGF-α for 15 min with or without 1 h pretreatment with 10 μM erlotinib. The cells were fixed and incubated with 5 μg of antibodies specific for EEA1, CD81, SR-BI, OCLN, and CLDN1/ml, followed by a 1:200 dilution of secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibodies. For staining of EGFR, cells were incubated with 1:200 dilution of an anti-EGFR antibody directly conjugated with Alexa 555. For studies analyzing the effect of anti-CD81 antibody treatment on EGFR localization, the cells were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 1:5 dilution of anti-CD81 (JS-81) or control IgG directly conjugated to FITC, washed with cold DMEM, and then shifted to 37°C for 1 h. The cells were then washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with the anti-EGFR-Alexa 555 antibody as described above. For studies analyzing the effect of anti-EGFR antibodies on endocytosis of EGFR, cells were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 10 μg of anti-EGFR (LA1 and cetuximab) or control antibodies/ml, washed with cold DMEM, and then shifted to 37°C for 1 h before being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. For studies analyzing the effect of EGFR kinase inhibitors on TGF-α-induced EGFR internalization, the cells were preincubated for 1 h at 4°C with 10 μM small molecule inhibitors (lapatinib, erlotinib, and protein kinase C [PKC] inhibitor), followed by treatment with 5 nM TGF-α for 15 min at 37°C before being fixed and incubated with anti-EGFR-Alexa 555 antibody or a 1:100 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-EEA1. The level of colocalized EGFR or CD81 with EEA1 was quantitated from confocal images from two independent experiments (each experiment was performed in duplicate) using the scoring module in Metamorph 7.5 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For each of the control treated cells (untreated and control immunoglobulin treated), between 48 and 69 cells were analyzed from four to eight confocal images. For each of the treatments with TGF-α (with or without inhibitors) or EGFR antibodies (LA1 and D1.5), between 98 and 217 cells were analyzed from 8 to 17 confocal images.

Statistical analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). All graphs represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) unless stated otherwise. P values for all data were determined using regular t test unless otherwise indicated (* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, and *** = P < 0.001; P values are denoted when appropriate). For quantitation of confocal images, one-way ANOVA was fit to the arcsine-square root transformed proportions. The arcsine-square root transformation was done to stabilize the residuals and reduce heteroskedasticity (unequal variance among groups). In each experiment, contrasts were fit to compare each treatment to the reference sample (either TGF-α-treated or the untreated control). Since there were multiple comparisons to the reference, P values were adjusted using Dunnett's procedure, as described previously (34).

RESULTS

EGFR activation is required for HCVcc entry at a step soon after CD81-CLDN1 binding but prior to initiating clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

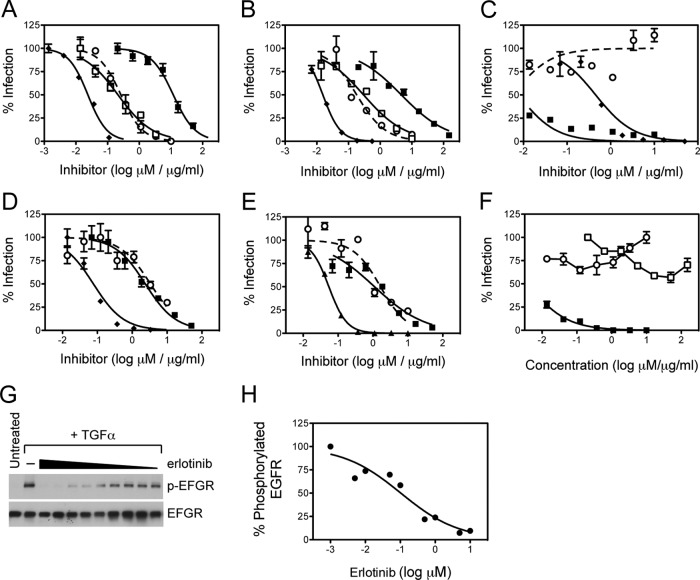

Using flow cytometry as well as immunohistochemical analyses of human liver sections, we confirmed that EGFR was expressed in Huh-7.5 hepatoma cells, although to higher levels compared to PHH (data not shown). In vitro neutralization studies using EGFR kinase inhibitors, erlotinib and lapatinib, demonstrated that EGFR activation was required for Con1/C3 and Jc1 HCVcc infection (the EC50s for Con1/C3 and Jc1 HCVcc are 276 and 180 nM, respectively) with antiviral potencies equivalent to that of erlotinib on TGF-α-mediated EGFR activation (181 nM, Fig. 1). However, as shown in Fig. 1, HCVpp were not inhibited to nearly the same extent as HCVcc (EC50s for Con1 and Jc1 HCVpp are 3340 and 1120 nM, respectively). Interestingly, H77 HCVpp was not inhibited by erlotinib even at concentrations as high as 10 μM (Fig. 1C). Erlotinib had no effect on HCV RNA replication (Fig. 1F) or HCV core release (data not shown), demonstrating that EGFR activation is required only for HCV entry.

Fig 1.

Huh-7.5 cells were pretreated with erlotinib (○), lapatinib (□), anti-CD81 antibody JS-81 (◆), or anti-E2 antibody AP33 (■) and infected with either Con1/C3 HCVcc (A), Jc1 HCVcc (B), H77 HCVpp (C), Con1 HCVpp (D), or J6CF HCVpp (E). The percent infection relative to untreated cells is plotted against concentrations of EGFR kinase inhibitors (erlotinib and lapatinib in μM) and antibodies (JS-81 and AP33 in μg/ml). These data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (F) Effect of erlotinib (○), AP33 (□) or danoprevir, an HCV protease inhibitor (■) on Jc1 HCVcc RNA replication. (G and H) Inhibition of TGF-α-induced EGFR activation by erlotinib (starting at 10 μM).

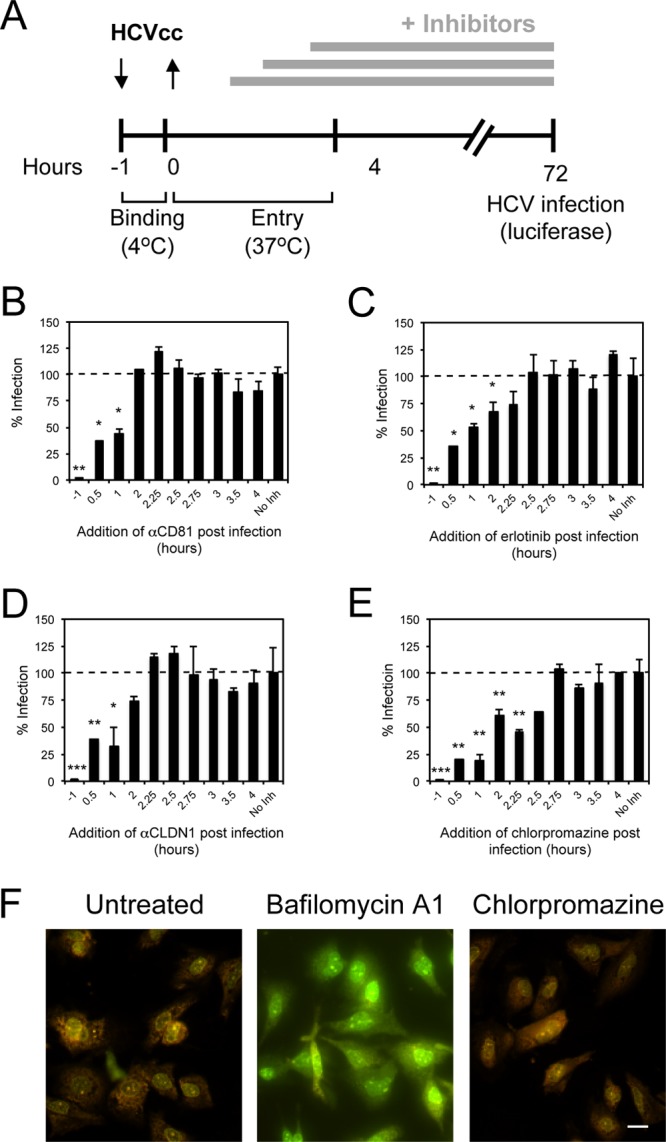

In order to identify the step at which EGFR was required for HCV entry, we performed a time-of-addition experiment in which Jc1-Rluc HCVcc was allowed to bind and infect Huh-7.5 cells for various lengths of time before erlotinib was added to the culture, and the extent of infection was measured 3 days later (Fig. 2A). As controls, we incubated parallel infections with chlorpromazine or neutralizing antibodies against CD81 (clone JS-81) and CLDN1 (clone 5.16v5). Chlorpromazine is a drug that causes the accumulation of clathrin in endosomal compartments and inhibits HCV entry by preventing the formation of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane (1). Treatment with any of the inhibitors 1 h prior to inoculation with HCVcc completely abrogated Jc1 HCVcc infection (Fig. 2B to E). Anti-CD81 and anti-CLDN1 antibodies were still effective at inhibiting entry if given 1 h after the initiation of HCVcc infection at 37°C but by 2 h had lost significant inhibition (Fig. 2B and D). In comparison, erlotinib was still effective if given 2 h after initiation of infection (Fig. 2C). In contrast, chlorpromazine still inhibited HCVcc entry when added as late as 2.5 h postinfection (Fig. 2E). Using acridine orange staining, we confirmed that as opposed to bafilomycin A1, chlorpromazine did not inhibit endosomal acidification in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that EGFR activation is required for HCV entry at a step occurring soon after CD81 and/or CLDN1 binding but prior to initiating clathrin-mediated HCV endocytosis.

Fig 2.

EGFR is required for HCVcc entry soon after CD81 binding but prior to clathrin-mediated endocytosis. (A to E) A time-of-addition experiment (depicted graphically in panel A) was performed in which Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1-Rluc HCVcc (MOI = 0.3) for 1 h at 4°C and transferred to 37°C in the absence (No Inh) or presence of anti-CD81 neutralizing antibody (B), erlotinib (C), anti-CLDN1 neutralizing antibody (D), or chlorpromazine (E) at various times after the temperature switch. As controls, cells were preincubated with inhibitors for 1 h prior to binding of virus at 4°C (−1). The percent infection (as measured by luciferase content) normalized to infection in the absence of inhibitor added is graphed against the time at which the inhibitors were added after the 37°C temperature switch. These data are representative of two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (F) Huh-7.5 cells were treated with 250 nM bafilomycin A1 or 50 μM chlorpromazine for 3 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with 5 μg of acridine orange/ml. Green (490-nm) and orange (570-nm) fluorescence was visualized. Although acridine orange fluoresces green at low concentrations, it accumulates in acidic endosomes and emits an orange fluorescence. Bar, 20 μm.

HCV particle binding to CD81 induces EGFR activation.

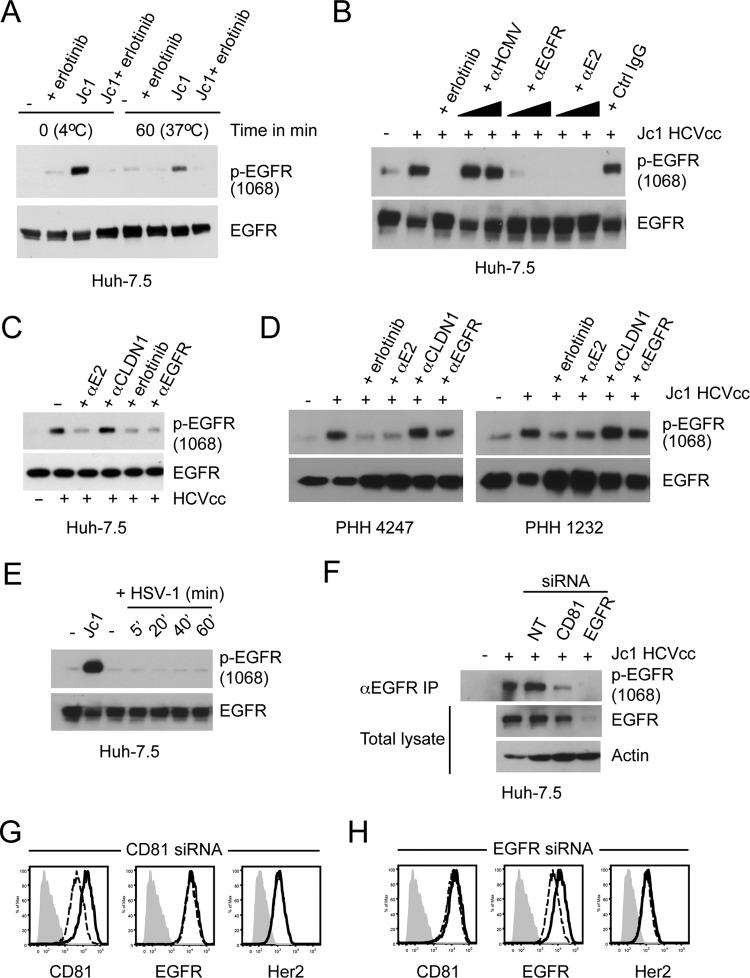

To determine whether HCV specifically induced EGFR activation to support entry, Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1 HCVcc at an MOI of ∼10, and EGFR activation was determined by anti-EGFR immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis to detect activated EGFR. Incubation of Jc1 HCVcc with Huh-7.5 cells at 4°C or after shifting to 37°C induced EGFR activation, which was sensitive to erlotinib (Fig. 3A). AP33, an antibody that inhibits interaction of the HCV E2 glycoprotein with CD81, completely eliminated HCV-induced EGFR activation (Fig. 3B). While cetuximab inhibited HCVcc-induced EGFR activation in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 3B and C), no inhibition was detected with the anti-CLDN1 5.16v5 antibody (Fig. 3C). HCVcc-induced EGFR activation was also blocked by AP33 but not 5.16v5 in PHH derived from two independent donors (Fig. 3D). Incubation of Huh-7.5 cells with another virus, HSV-1, did not result in EGFR activation (Fig. 3E). To further confirm that CD81 is required for HCVcc-induced EGFR activation, we transfected cells with nontargeting (NT), CD81-specific, or EGFR-specific siRNAs prior to incubation with Jc1 HCVcc. Although the NT siRNA did not affect HCVcc-induced EGFR activation, both CD81-specific and EGFR-specific siRNAs significantly inhibited HCVcc-induced EGFR activation (Fig. 3F). A negative control Her2-specific siRNA did not affect HCVcc-induced EGFR activation (data not shown). Cell surface expression of CD81 and EGFR confirmed that the siRNAs specifically decreased expression of their respective target genes (Fig. 3G and H). Altogether, these data demonstrate that HCVcc binding to CD81 induces EGFR activation and is required for viral entry.

Fig 3.

Induction of EGFR activation by HCVcc binding to CD81. For all experiments, total EGFR was immunoprecipitated, and Western blot analyses were performed with an antibody specific for activated EGFR (phosphorylated at Tyr-1068). Total EGFR was detected as a loading control. (A) Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 10) in the absence or presence of 10 μM erlotinib for 1 h at 4°C and then transferred to 37°C for an additional 1 h. (B) Huh-7.5 cells were treated with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 10) alone or in the presence of 10 μM erlotinib or two concentrations each of anti-HCMV, anti-EGFR cetuximab, and anti-E2 AP33 (10 and 30 μg/ml). Control IgG was used at 30 μg/ml. Huh-7.5 cells (C) or PHH derived from two independent donors (D) were treated with HCVcc for 1 h alone or in the presence of various inhibitors: 10 μM erlotinib or 30 μg/ml each of anti-E2 (AP33), anti-CLDN1 (5.16v5), and anti-EGFR (D1.5). EGFR was immunoprecipitated and assessed as described above. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments. (E) EGFR activation in Huh-7.5 cells incubated with HSV-1 (MOI = 10) for various times (5, 20, 40, and 60 min). Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 10) was used as a control. These data are representative of two independent experiments. (F) Inhibition of HCVcc-induced EGFR activation by CD81 siRNA. Huh-7.5 cells were transfected with nontargeting (NT), CD81-specific, or EGFR-specific siRNAs; at 48 h posttransfection, the cells were incubated with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 10), and EGFR activation was detected as described above. Total EGFR and actin were detected by Western blotting using input lysates. In parallel, the surface expression of CD81 and EGFR (dashed lines) was measured after transfection with (G) CD81-specific or (H) EGFR-specific siRNA. Isotype control antibody-stained and NT siRNA-transfected cells are shown in gray and as solid lines, respectively. Her2 expression was measured as a negative control. These data are representative of three independent experiments.

EGFR ligands enhance the rate of HCVcc entry by inducing CD81-EGFR colocalization and endocytosis.

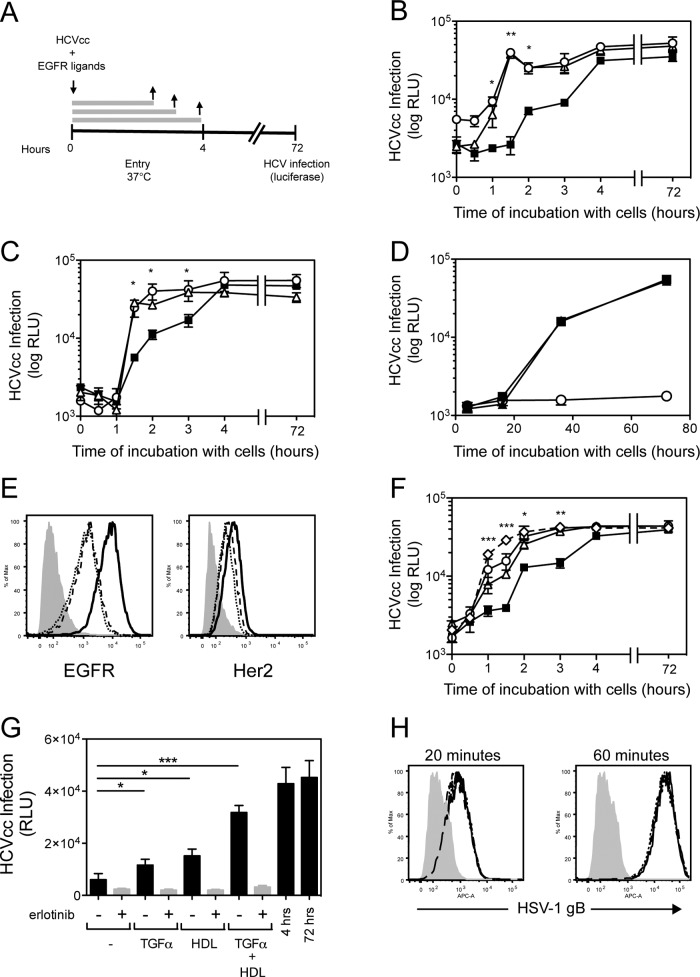

Since EGFR ligands (EGF and TGF-α) induce receptor dimerization and activation, we first wanted to determine whether EGFR ligands affected the rate of HCVcc entry. Jc1-Rluc HCVcc was incubated with Huh-7.5 cells for different times in the presence or absence of EGF or TGF-α (Fig. 4A). Incubation of Jc1-Rluc HCVcc with cells for ca. 3 to 4 h was sufficient to yield maximal infection (Fig. 4B; compare this to when the virus was incubated with cells for the entire duration of the assay [72 h]). In comparison, when Jc1-Rluc HCVcc was incubated with cells for only 1.5 h in the absence of EGFR ligand, infection was 8- to 12-fold less efficient (Fig. 4B, C, And F). In contrast, HCVcc incubation for 1.5 h in the presence of EGFR ligands resulted in infection rates similar to that detected after incubation for 4 or 72 h (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, cetuximab did not inhibit TGF-α-induced enhancement of the rate of HCVcc entry (Fig. 4C). No effect on HCVcc infection was detected if Jc1-Rluc was allowed to enter cells prior to addition of TGF-α, demonstrating that EGFR ligands specifically increase the rate of HCV entry rather than the rate of HCV RNA replication or polyprotein translation (Fig. 4D). TGF-α or EGF treatment decreased cell surface expression of EGFR (∼5.5- and ∼6.9-fold, respectively) but not HER2 (∼1.5-fold) in Huh-7.5 cells compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4E), a finding consistent with the fact that EGFR ligands induce EGFR internalization.

Fig 4.

TGF-α and EGF enhance the kinetics of HCVcc entry. (A) A time-of-addition experiment was performed in which Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1-Rluc HCVcc (MOI = 0.3) in the presence of ligands at 37°C for various times up to a maximum of 4 h, after which virus and ligands were removed, and cultures were replenished with fresh cDMEM. As a control for maximal infection, virus was incubated with cells for the entire duration of the assay (72 h). HCVcc infection was measured based on luciferase readings normalized to infection without ligand treatment. A time-of-addition experiment was performed in which Huh-7.5 cells were left untreated (■) or treated either with 12.5 nM TGF-α (△) or 16 nM EGF (○) (B) or with 12.5 nM TGF-α with (○) or without (△) cetuximab (C). These data are representative of two independent experiments. (D) TGF-α does not affect the rate of HCV RNA replication or polyprotein translation. Jc1-Rluc was incubated with cells at 37°C for 4 h to allow for entry to occur and then left untreated (■) or treated with 12.5 TGF-α (●), and HCV RNA replication was measured by luciferase at various times after entry (4, 16, 36, or 72 h). Background luciferase was measured in mock-infected cells (○). (E) Cell surface expression of EGFR and HER2 in Huh-7.5 cells untreated (solid line) or treated with TGF-α (dotted line) or EGF (dashed line). Cells stained with secondary antibody alone are shown in gray. (F) A time-of-addition experiment was performed in which Jc1-Rluc HCVcc (MOI = 0.3) was incubated with Huh-7.5 cells (■) or cells treated with 12.5 nM TGF-α (△), 10 μg of HDL/ml (○) or TGF-α+HDL (♢). (G) Effect of erlotinib on HDL-mediated enhancement of the rate of HCV entry. Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 0.3) for 1.5 h plus TGF-α, HDL, or TGF-α+HDL in the presence or absence of erlotinib, after which the inoculum was removed, and the cultures were replenished with fresh DMEM for the remainder of the assay (72 h). As controls, Jc1 HCVcc was incubated with cells for either 4 or 72 h, which resulted in an equivalent outcome of infection. These data are representative of two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (H) Effect of TGF-α and/or HDL on the kinetics of HSV-1 entry. Huh-7.5 cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI = 1 and incubated with TGF-α, HDL, or TGF-α+HDL for 20 or 60 min. Infection was monitored at 18 h by flow cytometry staining for HSV-1 gB.

Since HDL has also been demonstrated to enhance the rate of HCVcc entry through SR-BI, we wanted to determine whether EGFR and SR-BI acted in the same or an independent internalization pathway. Although HCVcc infection of Huh-7.5 cells in the presence of either HDL or TGF-α enhanced HCVcc entry, the addition of TGF-α+HDL further enhanced the rate of HCVcc entry (Fig. 4F and G). However, erlotinib inhibited both TGF-α- and HDL-induced enhancement of the rate of HCVcc entry (Fig. 4G). TGF-α- and HDL-induced enhancement of the rate of HCVcc entry in Huh-7.5 cells was specific to HCVcc since TGF-α and/or HDL did not affect the kinetics of HSV-1 entry in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 4H). These data demonstrate that enhancement of the rate of HCVcc entry by HDL requires EGFR activation, suggesting that SR-BI and EGFR may cooperate within the same internalization pathway to enhance HCV entry.

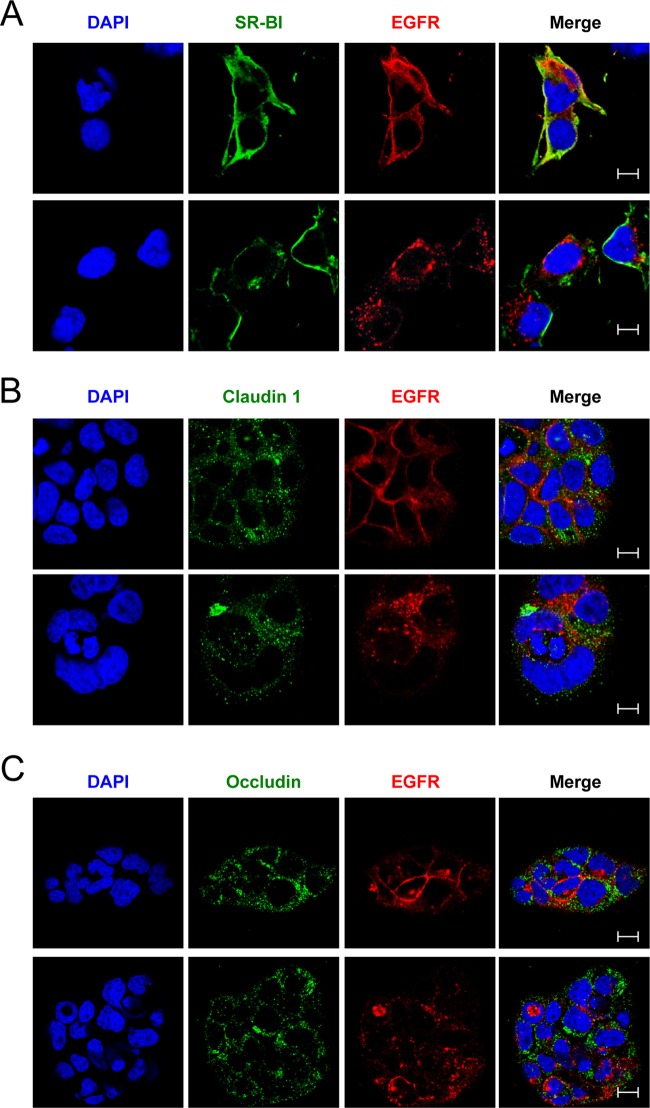

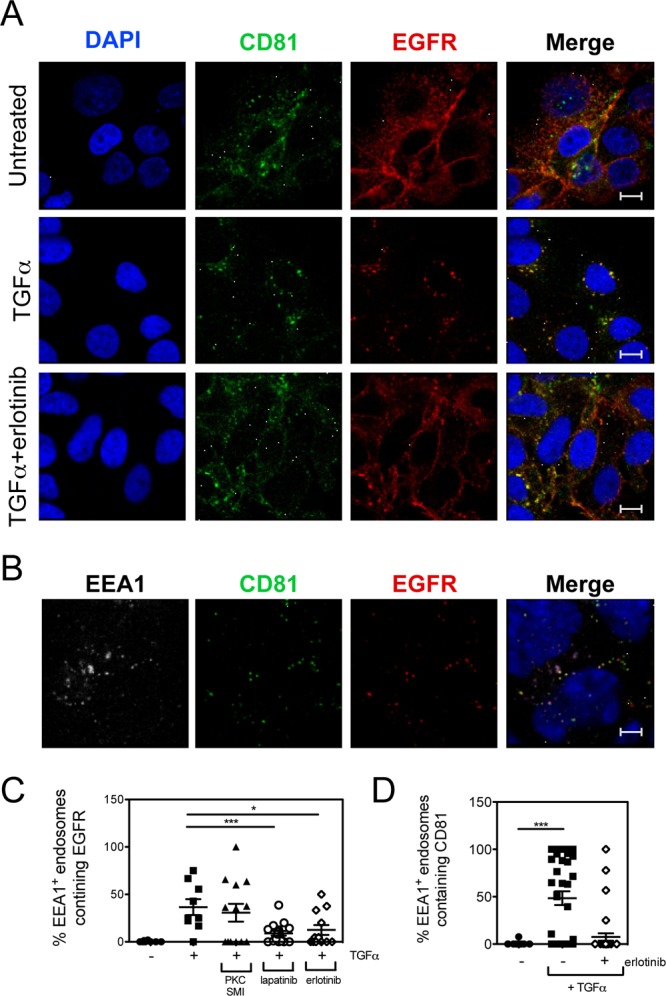

Since our data suggest that EGFR internalization may be important for HCV entry, we wanted to determine whether EGFR interacted with any HCV host receptors after treatment with EGFR ligands. HCV receptor (CD81, SR-BI, OCLN, and CLDN1) expression and localization was assessed by confocal microscopy in Huh-7.5 cells treated with or without TGF-α. In untreated cells, EGFR and the HCV receptors exhibited staining patterns consistent with plasma membrane expression (Fig. 5A and 6). Interestingly, TGF-α treatment resulted in significant colocalization between EGFR and CD81 but no other HCV receptors (Fig. 5A and 6). Similar colocalization of EGFR and CD81 was detected after treatment with EGF (data not shown). TGF-α-induced EGFR-CD81 colocalization was sensitive to erlotinib (Fig. 5A), and a fraction of the EGFR-CD81 colocalized staining was associated with early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), a marker of early endosomes (Fig. 5B). This was further confirmed by quantitating the number of EEA1+ endosomes that also contained either EGFR (Fig. 5C) or CD81 (Fig. 5D) in TGF-α-treated cells. In the absence of TGF-α, there was virtually no detection of EGFR or CD81 in EEA1+ endosomes. In contrast, TGF-α-induced kinase activation resulted in a significant increase in the number of EEA1+ early endosomes staining positive for EGFR or CD81 (Fig. 5C and D). These data demonstrate that EGFR activation induces CD81 internalization, perhaps in association with EGFR.

Fig 5.

TGF-α-mediated internalization of EGFR and CD81. (A) Huh-7.5 cells were treated with 5 nM TGF-α in the presence or absence of 5 μM erlotinib for 15 min at 37°C and fixed with paraformaldehyde, and immunofluorescence staining was performed with antibodies against CD81 and EGFR. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Endosomal localization of EGFR and CD81 after TGF-α treatment. Huh-7.5 cells treated with TGF-α were costained for EGFR and EEA1, a marker of early endosomes. These are representative data for three independent experiments. Colocalization of EEA1 with EGFR (C) or CD81 (D) was quantitated after TGF-α treatment in the presence or absence of erlotinib or lapatinib using the scoring module in Metamorph 7.5. A PKC inhibitor was used as a negative control. Each data point corresponds to individual confocal image fields containing an average of 12 ± 9 and 15 ± 6 cells per field for panels C and D, respectively. P values (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001) were calculated by using one-way analysis of variance as described in Materials and Methods and compared to TGF-α-treated (C) and untreated (D) cells.

Fig 6.

(A to C) Expression and colocalization of EGFR with SR-BI (A), CLDN1 (B), and OCLN (C) in untreated and TGF-α-treated Huh-7.5 cells. Huh-7.5 cells were treated with 5 nM TGF-α for 15 min at 37°C and fixed with paraformaldehyde, and immunofluorescence staining was performed with antibodies against EGFR and either CD81, SR-BI, claudin 1, or occludin. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Bar, 10 μm. These data are representative of two independent experiments.

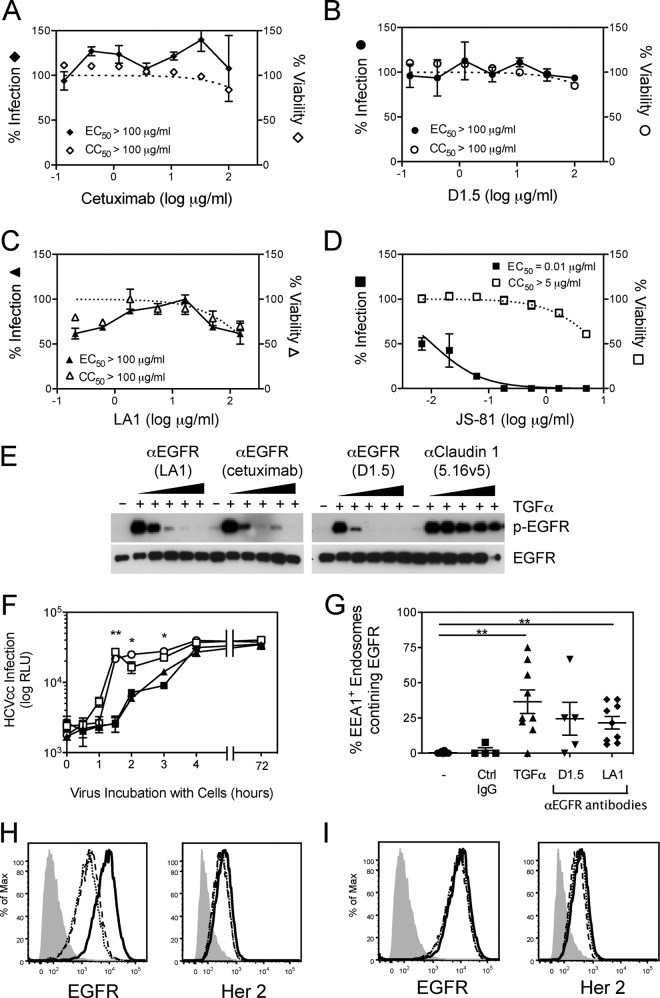

Inhibiting EGFR ligand binding or EGFR downstream signaling pathways does not inhibit HCVcc infection.

To address whether EGFR ligands and subsequent activation of the receptor are essential for HCV entry, neutralization assays were performed using three independent anti-EGFR antibodies that inhibit ligand binding (cetuximab, LA1, and D1.5). In contrast to the positive control anti-CD81 (JS-81) antibody, none of the anti-EGFR antibodies inhibited Jc1 HCVcc infection even at concentrations as high as 100 μg/ml (Fig. 7A to D). Similar results were obtained against Con1/C3-neo HCVcc (data not shown). As expected, these anti-EGFR antibodies inhibited TGF-α-dependent activation of EGFR in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 7E). In order to test whether EGFR signaling was required for HCV entry, we tested the ability of a panel of small-molecule inhibitors of various downstream EGFR signaling pathways to inhibit HCVcc entry. Although inhibition of PKC by bis-indolylmaleimide did have a modest effect on HCVcc entry (EC50 = ∼3.8 μM), inhibition of JAK, AKT, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Ras, Raf/Mek/Erk, or phospholipase C did not significantly inhibit HCVcc entry even at 10 μM inhibitor concentrations (Table 1).

Fig 7.

Effect of anti-EGFR antibodies on HCVcc entry. (A to D) Neutralization experiments were performed by incubating dilutions of anti-EGFR antibodies with Huh-7.5 cells, followed by infection with Jc1 HCVcc (MOI = 0.3). Infection (solid line) and cellular cytotoxicity (dotted line) were measured 3 days later. Listed are the concentrations of inhibitors resulting in 50% inhibition of HCV infection (EC50) and cellular cytotoxicity (CC50). (E) Inhibition of TGF-α-mediated EGFR activation by anti-EGFR antibodies. Huh-7.5 cells were treated with TGF-α alone or in the presence of various concentrations of LA1, cetuximab, or D1.5 (3-fold dilutions starting at 10 μg/ml). Anti-CLDN1 antibody 5.16v5 was used as a negative control. (F) A time-of-addition experiment was performed in which Huh-7.5 cells infected with Jc1 HCVcc were left untreated (■) or treated with cetuximab (○), D1.5 (□), or anti-HCMV (▲) antibodies for different times for a maximum of 4 h and infection was measured 3 days later. (G) Huh-7.5 cells were treated 5 nM TGF-α for 15 min or 10 μg of cetuximab or D1.5/ml for 1 h at 4°C, followed by another 1 h at 37°C, fixed, and stained for EEA1 and EGFR. EEA1-EGFR-colocalized staining was quantitated as described in Materials and Methods. Each data point corresponds to individual confocal image fields containing an average of 12 ± 8 cells per field. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (H and I) Cell surface expression of EGFR and HER2 in untreated Huh-7.5 cells (solid line) or after treatment with anti-EGFR antibodies (D1.5 [dotted line] or cetuximab [dashed line]) (H) or control antibodies (anti-HMCV [dotted line] or anti-Her2 [dashed line]) (I). Cells stained with secondary antibody alone are denoted by the filled gray curve. These data are representative of two independent experiments.

Table 1.

Effect of inhibiting EGFR downstream signaling pathways on HCVcc entrya

| Inhibitor | Target | EC50 (nM) | CC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erlotinib | EGFR | 19 ± 4.1 (n = 15) | >10,000 |

| Lapatinib | EGFR/Her2 | 32.8 ± 26 (n = 3) | >10,000 |

| Imatinib (Gleevec) | Abl | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Geldamycin | Hsp90 | 413 (n = 1) | 393 (n = 1) |

| 17AAG | Hsp90 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Sorafenib | RAF/MEK/ERK | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid | Ras | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Calbiochem 44937 | MEK | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| U73122 | Phospholipase C | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| LY294002 | PI3K | >10,000 | ∼6,784 |

| Calbiochem 124018 | AKT1/2 | >10,000 | ∼6,445 |

| Calbiochem 124005 | AKT | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Bis-indolylmaleimide I | PKC | 3,873 ± 474 (n = 2) | >10,000 |

| Calbiochem 539654 | PKCβ | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Calbiochem 539652 | PKC/EGFR | 152 ± 120 (n = 2) | >10,000 |

| Calbiochem 420097 | JAK | >10,000 | >10,000 |

Neutralization experiments were performed by incubating dilutions of small-molecule inhibitors with Huh-7.5 cells, followed by infection with Jc1 HCVcc. Infection was measured 3 days later by RT-qPCR. The concentrations of inhibitors resulting in 50% inhibition of infection (EC50) and cellular cytotoxicity (CC50) are given. These are representative data (means ± the SEM) for at least three replicates except for bisindolylmaleimide and Calbiochem 539652 treatments, which were each tested only twice. Geldamycin was tested once due to significant cellular toxicity as detected in this 3-day assay.

Since cetuximab did not block TGF-α-induced enhancement of the rate of HCV entry and has been demonstrated to induce EGFR internalization, we performed a time-of-addition experiment using cetuximab and D1.5 to determine whether anti-EGFR antibody binding had any effect on HCVcc entry in the absence of EGFR ligands. Infection in the presence of cetuximab or D1.5 for 1.5 h significantly enhanced infection compared to infection in the absence of antibodies (Fig. 5E). No effect was detected with anti-HCMV (Fig. 7F) or anti-HER2 (data not shown) negative control antibodies. Treatment with either cetuximab or D1.5 antibodies (but not the negative control antibodies) also resulted in decreased EGFR but not HER2 cell surface expression (Fig. 7H and I). To confirm that the decrease in cell surface EGFR expression was due to increased receptor internalization, we performed confocal microscopy and quantitated the level of colocalization between EGFR and EEA1. TGF-α treatment was used as a positive control. Both cetuximab and D1.5 significantly increased EGFR internalization, as measured by an increase in EEA1-EGFR colocalization (Fig. 7G). These data demonstrate that while EGFR ligands can enhance the rate of HCV entry in vitro, EGFR internalization rather than ligand-dependent activation of EGFR or EGFR signaling events is required for HCV entry.

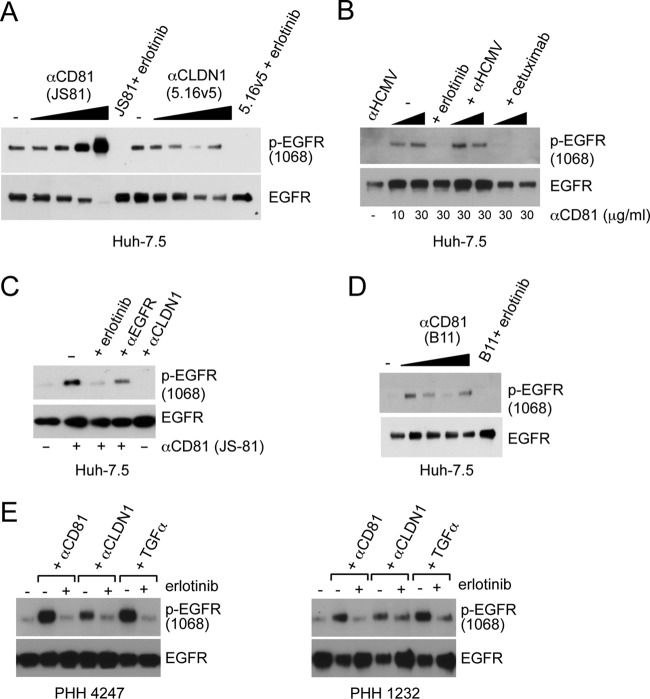

CD81 cross-linking induces EGFR activation and internalization.

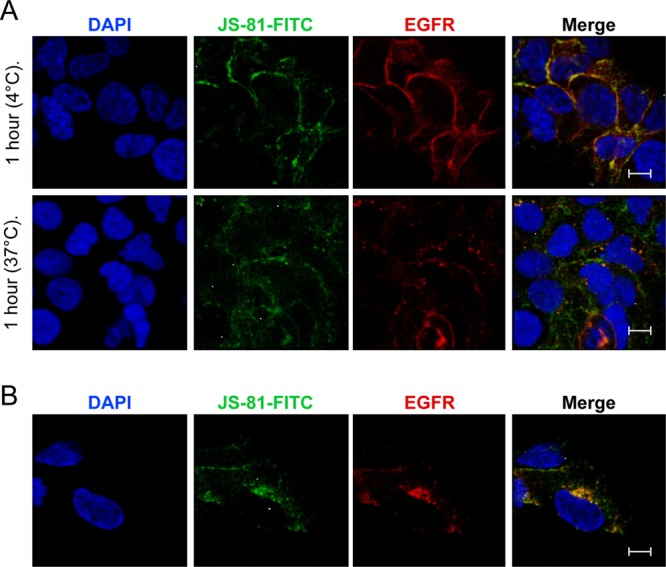

Since CD81 was required for HCVcc-dependent EGFR activation, we treated Huh-7.5 cells with different concentrations of the anti-CD81 cross-linking antibody, JS-81, to determine whether cross-linking CD81 induced EGFR activation. Incubation of Huh-7.5 cells with anti-CD81 (JS-81 and B11) but not anti-CLDN1 (5.16v5) antibodies induced EGFR activation, which was inhibited by erlotinib and cetuximab (Fig. 8A to D). Similar effects of anti-CD81 antibodies were detected in PHH (Fig. 8E). Interestingly, the anti-CLDN1 neutralizing antibody modestly induced EGFR activation in PHH (Fig. 8E) but not in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 8A and C). No additive effect on EGFR activation was detected when Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with both anti-CD81 and anti-CLDN1 antibodies (data not shown). In order to determine whether CD81 cross-linking induced colocalization and internalization of EGFR, we treated live Huh-7.5 cells with FITC-labeled anti-CD81 antibody (JS-81-FITC) and determined the effect on EGFR localization after 1 h of incubation at 4°C or after a temperature switch to 37°C for an additional hour (Fig. 9A). No alteration in EGFR localization was detected using a FITC-labeled negative control IgG if incubated at 0 or 37°C (data not shown). Incubation of cells with JS-81-FITC at 0°C did not induce EGFR-CD81 internalization; this is consistent with the fact that active endocytosis occurred at 37°C but not 0°C. In contrast, incubation with JS-81-FITC at 37°C induced EGFR-CD81 internalization (Fig. 9), demonstrating that CD81 cross-linking leads to internalization of EGFR.

Fig 8.

CD81 cross-linking induces EGFR activation. (A) Huh-7.5 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of anti-CD81 or anti-CLDN1 antibodies (3-fold dilutions starting at 30 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. (B) EGFR activation in Huh-7.5 cells treated 10 or 30 μg of anti-CD81 JS-81/ml for 1 h at 37°C. Cells treated with 30 μg of JS-81/ml were treated with 10 μM erlotinib, anti-HCMV, or cetuximab antibodies (each at 10 and 30 μg/ml). (C) Huh-7.5 cells incubated with 30 μg of anti-CD81 antibody JS-81/ml alone or in the presence of various other agents: 10 μM erlotinib, 10 μg of anti-EGFR (D1.5)/ml, or 30 μg anti-CLDN1 (5.16v5)/ml. (D) Huh-7.5 cells treated with 3-fold dilutions of anti-CD81 antibody (clone B11) starting at 30 μg/ml. Cells treated with 30 μg of B11/ml were treated with erlotinib. (E) EGFR activation in PHH from two independent donors treated with anti-CD81 (JS-81) antibody (30 μg/ml), anti-CLDN1 (30 μg/ml), or TGF-α (5 nM) alone or in the presence of 10 μM erlotinib. These data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Fig 9.

CD81 cross-linking induces CD81-EGFR colocalization and internalization. (A) Huh-7.5 cells were incubated with FITC-labeled control or anti-CD81 antibodies for 1 h at 4°C or shifted to 37°C for another hour. Cells were fixed and stained for EGFR. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. (B) Additional image of an anti-CD81-FITC-treated cell after incubation for an hour at 37°C. No intracellular EGFR-CD81 colocalization was detected at 4°C. Bar, 10 μm. These data are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that direct HCV binding to CD81 can induce EGFR activation and internalization, without apparent involvement of CLDN1. Moreover, CD81 associates with EGFR and internalization of CD81-HCV complexes appears to depend on EGFR. EGFR kinase inhibitors block HCV infection by abrogating EGFR internalization rather than inhibiting downstream signaling cascades. Recently, Lupberger et al. (28) have demonstrated that EGFR kinase inhibitors block HCV entry and have proposed that EGFR is important for HCV glycoprotein-dependent fusion with host membranes, perhaps because it regulates CD81-CLDN1 associations necessary for HCV entry. We propose that CD81 cointernalizes with EGFR and that this is the step in HCV entry that is blocked by EGFR kinase inhibitors. EGFR has also been demonstrated to play a critical role in the entry process of other viruses, including influenza A virus, adeno-associated virus serotype 6, and HCMV. Interestingly, EGFR activation was demonstrated to be required for influenza A virus internalization via the clustering of lipid rafts (9), suggesting that EGFR internalization may be a common mechanism utilized by viruses to enter cells.

Treatment of cells with the EGFR ligands significantly increased the rate at which HCVcc entry occurred and lead to EGFR endocytosis (Fig. 3 and 4). Our data suggest that EGFR activation is required for HCVcc particle endocytosis for the following reasons. First, the erlotinib time-of-addition experiment demonstrates that EGFR activation is required prior to clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Fig. 2). Second, binding of HCVcc particles to hepatocytes induce EGFR activation at 4°C, a temperature at which endocytosis should not be occurring (Fig. 3A). Although erlotinib efficiently inhibited Con1/C3 and Jc1 HCVcc entry, it was less effective against the majority of HCVpp tested. This is in contrast to data from Lupberger et al. (28), who show equivalent efficacy against HCVcc and HCVpp. It is currently unclear what the differences between the HCVpp and HCVcc stocks are, but there are increasing data suggesting that HCVpp entry may not fully reproduce HCVcc entry, including differences in subcellular localization of particle assembly and virion-associated lipoprotein (4, 20, 22, 35, 46). In addition, HCVcc but not HCVpp were found to be sensitive to inhibitors of a recently identified HCV entry factor, the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) cholesterol uptake receptor (45). It was also surprising to find that inhibition of downstream EGFR signaling pathways had no significant effects on HCV entry (Table 1). Only inhibition of PKC resulted in a modest decrease in HCV entry; this is consistent with published data demonstrating that phorbol ester-mediated activation of PKC enhanced HCVpp entry (29). No inhibition of HCVcc entry was detected using farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (Salirasib), a Ras antagonist that is undergoing human clinical trials for pancreatic cancer and non-small-cell lung cancer. Although Lupberger et al. (28) demonstrate that erlotinib or EGFR-specific siRNAs result in an ∼2-fold decrease in a cell-cell fusion assay, this does not compare to the complete inhibition of HCV entry by erlotinib. These data suggest that EGFR may be more critical in HCV entry at steps other than endosome fusion.

We have found that EGFR internalization is important for HCV entry. EGFR ligands induce receptor internalization and enhance the kinetics of HCV entry. Interestingly, EGF seemed to be more potent than TGF-α in enhancing the rate of HCVcc entry at early times (t = 0 to 30 min, Fig. 4B). Although the reason for this is unclear, it may be due to the ∼20-fold-higher receptor affinity of EGF versus TGF-α (52). EGFR ligands also induced redistribution of CD81 and EGFR from the plasma membrane to cytoplasmic vesicles, some of which correlate to early endosomes (Fig. 5). Multiple ligands including ceramide and, more recently, HCV particles, have been demonstrated to induce CD81 endocytosis (14, 54). Our data suggest that ligand-dependent EGFR activation and endocytosis may be one of the mechanisms by which CD81 internalization occurs. While some CD81 and EGFR colocalization was detected by confocal microscopy after HCVcc binding, demonstrating a difference compared to untreated cells was challenging due to the low MOI and high CD81 and EGFR cell surface expression (data not shown). Our data also suggest that EGFR ligands are not essential for HCV entry as three anti-EGFR antibodies, which prevent ligand binding had no effect on HCVcc (Fig. 7) or HCVpp entry (data not shown). Cetuximab, LA1, and D1.5 all inhibit EGF/TGF-α binding (15, 48). Cetuximab did not prevent TGF-α-induced enhancement of the rate of HCVcc entry (Fig. 4C). In fact, treatment of cells with these antibodies induced EGFR endocytosis and enhanced the rate of HCVcc entry to a similar extent, as seen with the EGFR ligands. These data suggest that while EGFR antibodies can prevent HCV-induced EGFR kinase activation, they enhance HCVcc entry by inducing EGFR endocytosis. This is consistent with published reports demonstrating that cetuximab, which inhibits EGFR activation by preventing a conformational change required for receptor dimerization, can induce EGFR internalization (24, 30, 31, 48). Although EGFR kinase activation is required for receptor endocytosis in vivo, we have shown that we can experimentally bypass the requirement of EGFR kinase activation for receptor endocytosis by using anti-EGFR antibodies and demonstrate that EGFR internalization in the absence of kinase activation can still facilitate HCV entry. In contrast, Lupberger et al. (28) demonstrated that LA1 treatment inhibited HCVcc infection. We have also tested LA1 and have found no inhibitory effect on either Jc1 HCVcc (Fig. 7C), Con1/C3-neo HCVcc (data not shown), or HCVpp (data not shown) entry.

Our data further identify CD81 as the key player that regulates HCV-induced EGFR activation for the following reasons. First, HCVcc-induced EGFR activation is blocked by AP33, an anti-HCV E2 antibody that prevents HCV E2-CD81 binding (Fig. 3B). Second, while RNA interference knockdown of CD81 expression did not affect EGFR expression levels, it led to a significant decrease in HCVcc-induced EGFR activation (Fig. 3F). Third, TGF-α-treatment or CD81 cross-linking can induce colocalization of CD81-EGFR and internalization (Fig. 5 and 9). Fourth, anti-CD81 neutralizing antibodies induce EGFR activation in Huh-7.5 and PHH cells (Fig. 8). CD81 is a multifunctional membrane protein that is essential for HCV entry in vitro and in vivo (33, 42). Using the JS-81 anti-CD81 cross-linking antibody, CD81 has been demonstrated to play multiple roles involved in HCV entry from initial binding of HCV to activation of multiple downstream pathways (3, 6). A CD81-associated protein, EWI-2wint, which interacts with CD81 and is expressed in several cell types except hepatocytes, exerts an inhibitory effect on HCV infection (36). Interestingly, another tetraspanin family member, CD82, has been demonstrated to bind EGFR and negatively regulate EGFR activation by preventing receptor dimerization (38, 39), suggesting that tetraspanin proteins may be critical regulators of EGFR activation. We have attempted to determine whether there is a protein-protein interaction between CD81 and EGFR. However, we could not demonstrate a physical CD81-EGFR interaction using EGFR immunoprecipitation, followed by mass spectrometry or Western blot analyses (data not shown). These data, however, do not rule out the possibility of a low-affinity CD81-EGFR interaction and/or requirement for additional adaptor molecules. Future studies are required to address these questions. Since confocal microscopy shows colocalization of EGFR and CD81 on the plasma membrane at 4°C (Fig. 9A) and the fact that HCV binding at 4°C can activate EGFR (Fig. 3A), it is quite possible that EGFR-CD81 association on the plasma membrane may exist even in the absence of virus binding. It is unclear whether any other HCV receptors play a role in HCV internalization or whether they act primarily as tropism entry factors. Although CLDN1 internalization was not detected after TGF-α treatment in Huh-7.5 cells, it was interesting that the anti-CLDN1 neutralizing antibody modestly induced EGFR activation in PHH (Fig. 8E) but not in Huh-7.5 cells (Fig. 8A and C). During the preparation of this manuscript, Farquhar et al. (14) demonstrated that HCV induces CD81 and CLDN1 internalization. Our data confirm their findings with regard to CD81 and further demonstrate that HCV induces CD81 internalization in an EGFR-dependent manner. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence to suggest a role for CD81 in EGFR activation and is key to our understanding of how EGFR function is regulated.

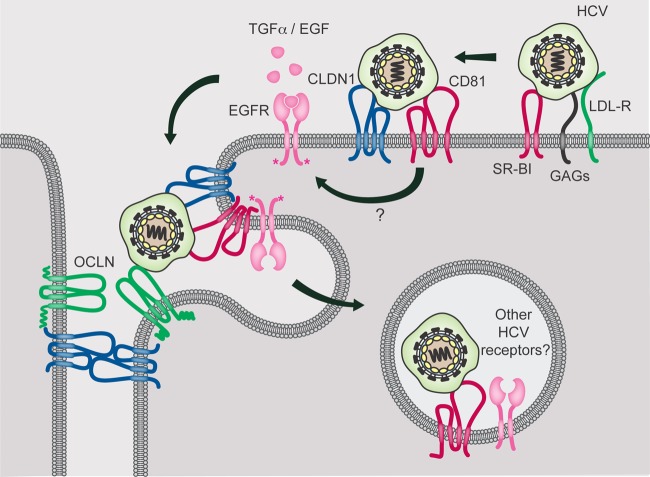

Our current data suggest that HCV has evolved to usurp EGFR ligand-mediated receptor internalization to enhance the rate of HCV entry as well as to induce EGFR activation and internalization. A model for the potential role of EGFR in HCV entry is presented in Fig. 10. After initial binding to LDL-R, GAGs, and SR-BI, HCV particles are transferred to CD81, which then forms a complex with CLDN1 (CD81-HCV-CLDN1). The interaction of CD81 with HCV leads to EGFR activation, which in turn results in the internalization of EGFR-CD81-HCV structures. The mechanism by which CD81 induces EGFR activation is currently unclear, but we hypothesize that CD81-cross-linking may lead to ligand-independent EGFR dimerization and activation. SR-BI-mediated uptake of HDL, which has been shown to enhance the kinetics of HCV entry (8, 57), also depends on EGFR activation and suggests a primary role for EGFR in HCV particle endocytosis. Our data suggest that HCV has evolved to take advantage of circulating levels of EGFR and SR-BI ligands in the blood to enhance the kinetics of infection and spread in vivo, since ligand binding to EGFR can induce the formation and endocytosis of EGFR-CD81-HCV structures to enhance the rate of HCV entry. Further studies are required to determine how CLDN1 plays a role in HCV endocytosis. It is interesting that EGFR overexpression is observed in ca. 40 to 70% of HCC, including those associated with HCV infection (10, 18, 51). Since chronic HCV-infected patients have very high levels of circulating HCV particles and are estimated to make 1012 HCV particles/day (37), it is conceivable that persistent EGFR stimulation over many years could be very important in the development and/or progression of HCV-related HCC.

Fig 10.

Proposed model for the role of EGFR in HCV entry. HCV binding to CD81 results in cross-linking of CD81 and EGFR kinase activation, which in turn induces cointernalization of HCV-CD81-EGFR. In addition, ligand binding to EGFR activates the receptor and induces EGFR and CD81 colocalization and endocytosis to enhance the rate of HCV entry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicholas Lewin-Koh for help with statistical analyses and Allison Bruce for assistance with generating the EGFR model figure. We also thank Mark Sliwkowksi, Rob Akita, Becket Feierbach, Lee Swem, and Eric J. Brown for helpful comments and suggestions.

J.D. and H.P. performed the experiments, L.D. analyzed the EGFR immunohistochemistry, H.N. quantitated the confocal images, G.S. provided scientific input, and S.B.K. reviewed the data and designed the overall experimental strategy.

All of the authors are employees of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, and are shareholders of Roche. This study was supported by internal Genentech funds.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Blanchard E, et al. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 80:6964–6972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradley DW. 2000. Studies of non-A, non-B hepatitis and characterization of the hepatitis C virus in chimpanzees. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 242:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brazzoli M, et al. 2008. CD81 is a central regulator of cellular events required for hepatitis C virus infection of human hepatocytes. J. Virol. 82:8316–8329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burlone ME, Budkowska A. 2009. Hepatitis C virus cell entry: role of lipoproteins and cellular receptors. J. Gen. Virol. 90:1055–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan G, Nogalski MT, Yurochko AD. 2009. Activation of EGFR on monocytes is required for human cytomegalovirus entry and mediates cellular motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:22369–22374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coffey GP, et al. 2009. Engagement of CD81 induces ezrin tyrosine phosphorylation and its cellular redistribution with filamentous actin. J. Cell Sci. 122:3137–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Compton T. 2004. Receptors and immune sensors: the complex entry path of human cytomegalovirus. Trends Cell Biol. 14:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dreux M, et al. 2006. High density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus-neutralizing antibodies by stimulating cell entry via activation of the scavenger receptor BI. J. Biol. Chem. 281:18285–18295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eierhoff T, Hrincius ER, Rescher U, Ludwig S, Ehrhardt C. 2010. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes uptake of influenza A viruses (IAV) into host cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001099 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Bassiouni A, et al. 2006. Immunohistochemical expression of CD95 (Fas), c-myc and epidermal growth factor receptor in hepatitis C virus infection, cirrhotic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. APMIS 114:420–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evans MJ, et al. 2007. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus coreceptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 446:801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farquhar MJ, et al. 2008. Protein kinase A-dependent step(s) in hepatitis C virus entry and infectivity. J. Virol. 82:8797–8811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farquhar MJ, Harris HJ, McKeating JA. 2011. Hepatitis C virus entry and the tetraspanin CD81. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39:532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farquhar MJ, et al. 2012. Hepatitis C virus induces CD81 and claudin-1 endocytosis. J. Virol. 86:4305–4316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garrett CR, Eng C. 2011. Cetuximab in the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 11:937–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harmon B, Campbell N, Ratner L. 2010. Role of Abl kinase and the Wave2 signaling complex in HIV-1 entry at a post-hemifusion step. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000956 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hotzel I, et al. 2011. Efficient production of antibodies against a mammalian integral membrane protein by phage display. Protein Eng. Design Selection 24:679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ito Y, et al. 2001. Expression and clinical significance of erb-B receptor family in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 84:1377–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones CT, Murray CL, Eastman DK, Tassello J, Rice CM. 2007. Hepatitis C virus p7 and NS2 proteins are essential for production of infectious virus. J. Virol. 81:8374–8383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kapadia SB, Barth H, Baumert T, McKeating JA, Chisari FV. 2007. Initiation of hepatitis C virus infection is dependent on cholesterol and cooperativity between CD81 and scavenger receptor B type I. J. Virol. 81:374–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kapadia SB, Chisari FV. 2005. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by host geranylgeranylation and fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:2561–2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keck ZY, et al. 2007. Immunogenic and functional organization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) glycoprotein E2 on infectious HCV virions. J. Virol. 81:1043–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koike K. 2007. Hepatitis C virus contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis by modulating metabolic and intracellular signaling pathways. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatology 22(Suppl 1):S108–S111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li S, et al. 2005. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell 7:301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lindenbach BD, et al. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lockhart AC, Berlin JD. 2005. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for colorectal cancer therapy. Semin. Oncol. 32:52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lupberger J, et al. 2011. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 17:589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mee CJ, et al. 2009. Polarization restricts hepatitis C virus entry into HepG2 hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 83:6211–6221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mendelsohn J. 2000. Blockade of receptors for growth factors: an anticancer therapy: the fourth annual Joseph H. Burchenal American Association of Cancer Research Clinical Research Award Lecture. Clin. Cancer Res. 6:747–753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mendelsohn J. 2001. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for cancer therapy. Endocrine-Related Cancer 8:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. 2006. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Semin. Oncol. 33:369–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meuleman P, et al. 2008. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology 48:1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller RG., Jr 1981. Simultaneous statistical inference, 2nd ed Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyanari Y, et al. 2007. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:1089–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Montpellier C, et al. 2011. Interacting regions of CD81 and two of its partners, EWI-2 and EWI-2wint, and their effect on hepatitis C virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 286:13954–13965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Neumann AU, et al. 1998. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 282:103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Odintsova E, Sugiura T, Berditchevski F. 2000. Attenuation of EGF receptor signaling by a metastasis suppressor, the tetraspanin CD82/KAI-1. Curr. Biol. 10:1009–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Odintsova E, Voortman J, Gilbert E, Berditchevski F. 2003. Tetraspanin CD82 regulates compartmentalisation and ligand-induced dimerization of EGFR. J. cell science 116:4557–4566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Owsianka A, et al. 2005. Monoclonal antibody AP33 defines a broadly neutralizing epitope on the hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 79:11095–11104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pietschmann T, et al. 2006. Construction and characterization of infectious intragenotypic and intergenotypic hepatitis C virus chimeras. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:7408–7413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pileri P, et al. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282:938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ploss A, et al. 2009. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 457:882–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raabe EH, et al. 2011. BRAF activation induces transformation and then senescence in human neural stem cells: a pilocytic astrocytoma model. Clin. Cancer Res. 17:3590–3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sainz B, Jr, et al. 2012. Identification of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor as a new hepatitis C virus entry factor. Nat. Med. 18:281–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sandrin V, et al. 2005. Assembly of functional hepatitis C virus glycoproteins on infectious pseudoparticles occurs intracellularly and requires concomitant incorporation of E1 and E2 glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 86:3189–3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scarselli E, et al. 2002. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 21:5017–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schaefer G, et al. 2011. A two-in-one antibody against HER3 and EGFR has superior inhibitory activity compared with monospecific antibodies. Cancer Cell 20:472–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sharma NR, et al. 2011. Hepatitis C virus is primed by CD81 protein for low pH-dependent fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 286:30361–30376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun Y, et al. 2012. Evolutionarily conserved paired immunoglobulin-like receptor alpha (PILRα) domain mediates its interaction with diverse sialylated ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 287:15837–15850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tanaka H. 1991. Immunohistochemical studies on epidermal growth factor receptor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 88:138–144 (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thoresen GH, et al. 1998. Response to transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) in hepatocytes: lower EGF receptor affinity of TGFα is associated with more sustained activation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and greater efficacy in stimulation of DNA synthesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 175:10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trotard M, et al. 2009. Kinases required in hepatitis C virus entry and replication highlighted by small interference RNA screening. FASEB J. 23:3780–3789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Voisset C, et al. 2008. Ceramide enrichment of the plasma membrane induces CD81 internalization and inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. Cell. Microbiol. 10:606–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yamamoto C, et al. 1999. Cycloprodigiosin hydrochloride, a new H+/Cl− symporter, induces apoptosis in human and rat hepatocellular cancer cell lines in vitro and inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. Hepatology 30:894–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. 2001. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zeisel MB, et al. 2007. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a key host factor for hepatitis C virus infection required for an entry step closely linked to CD81. Hepatology 46:1722–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhong J, et al. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]