Abstract

Noroviruses (NoVs) bind to histo-blood group antigens, namely, ABH antigens and Lewis antigens. We previously showed the NoVs GI/2, GI/3, GI/4, and GI/8 were able to strongly bind to Lewis a (Lea) antigen, which is expressed by individuals who are nonsecretors. In this study, to investigate how Lewis antigens interact with GI NoV virion protein 1 (VP1), we determined the crystal structures of the P domain of the VP1 protein from the Funabashi 258 (FUV258) strain (GI/2) in complexes with Lea, Leb, H type 1, or A type 1 antigens. The structures were compared with those of the NV/68 strain (GI/1), which does not bind to the Lea antigen. The four loop structures, loop P, loop S, loop A, and loop B, continuously deviated by more than 2 Å in length between the Cα atoms of the corresponding residues of the FUV258 and NV/68 P domains. The most pronounced differences between the two VP1 proteins were observed in the structures of loop P. In the FUV258 P domain, loop P protruded toward the next protomer, forming a Lea antigen-binding site. The Gln389 residue make a significant contribution to the binding of the Lea antigen through the stabilization of loop P as well as through direct interactions with the α4-fucosyl residue (α4Fuc) of the Lea antigen. Mutation of the Gln389 residue dramatically affected the degree of binding of the Lewis antigens. Collectively, these results suggest that loop P and the amino acid residue at position 389 affect Lewis antigen binding.

INTRODUCTION

Norovirus (NoV) is a member of the family Caliciviridae (1) and is a major causative agent of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in humans. It is well known that NoV strains isolated worldwide are morphologically similar but antigenically diverse (8, 10, 20). Genetic analysis has resulted in the classification of human NoV strains into at least three genogroups: genogroup I (GI), GII, and GIV, which contain at least 15 genotypes, 18 genotypes, and 1 genotype, respectively (18).

The interactions of NoVs with histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) are thought to play a critical role in the infection process. HBGAs are structurally related oligosaccharides and include ABH antigens and Lewis antigens. Different norovirus genotypes exhibit different patterns of HBGA binding (11, 14, 34, 35). Currently, it is suggested that HBGAs function as putative receptors or coreceptors for NoV (22). The precursors of HBGAs are classified into four major core structures: type 1 (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-), type 2 (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-), type 3 (Galβ1-3GalNAcα1-), and type 4 (Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-). In erythrocytes, FUT1, which is a member of the fucosyltransferase family, generates ABH antigens through the transfer of an α2-fucosyl residue (α2Fuc) to the precursors. Meanwhile, the transfer of α2Fuc is catalyzed in saliva and mucosal secretions by FUT2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (29). FUT2 is essential for transferring an α2Fuc to the type 1 core structure, which is required to generate the H type 1 antigen (Fucα1-2Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-), a precursor for Lewis b [Leb; Fucα1-2Galβ1-3(Fucα1-4)GlcNAcβ1-], in secretions (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Further, FUT3 catalyzes the transfer of α4Fuc to the type 1 precursor and the H type 1 antigen to generate Lewis a [Lea; Galβ1-3(Fucα1-4)GlcNAcβ1-] and Leb, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The Lewis antigen is genetically determined by polymorphisms in the FUT2 and FUT3 genes (21, 27). Leb expression requires both FUT2 and FUT3, while Lea expression requires only FUT3. FUT2 and FUT3 are primarily expressed in the epithelial cells of gastrointestinal tissues, so Lewis antigen is primarily expressed in this cell type (26). The A type 1 antigen [GalNAcα1-3(Fucα1-2)Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-] is generated by the addition of GalNAc to the terminal Gal of the H type 1 antigen, and the B type 1 antigen [Galα1-3(Fucα1-2)Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-] is produced by the addition of Gal to the terminal Gal (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Humans are divided into two groups, secretors and nonsecretors, depending on whether or not they secrete H, A, B, and Leb antigens. Nonsecretors who have null FUT2 alleles cannot synthesize H, A, B, and Leb antigens in secretions, although these individuals can express HBGAs in erythrocytes owing to FUT1 (19). Therefore, Lea is the dominant antigen having a type 1 core structure in the epithelial cells of nonsecretors.

When the NoV VP1 gene, which encodes a capsid protein, is expressed in insect cells, the products are self-assembled into virus-like particles (VLPs) and released into culture media (17, 45). VLPs have been subjected to experiments to investigate their interaction with HBGAs (11, 13, 14, 22, 23, 34, 35). VLPs derived from the Norwalk virus (NV/68), which is the prototype strain of NoV and a GI genotype 1 (GI/1) strain, bind to HBGAs in saliva from secretor individuals, and they preferentially bind to H type 1 and Leb synthetic carbohydrates (11, 13, 14, 22, 23). The α2Fuc residue was required for the binding of NV/68 VLPs to HBGAs, because NV/68 VLPs did not bind to the Lea antigen, which lacks the terminal α2Fuc (15). Although NV/68 VLPs bind to type A antigen in saliva and synthetic type A carbohydrate, they bind to neither type B synthetic carbohydrate nor the majority of type B antigens in saliva (11, 13, 14, 22). Previous volunteer challenge studies indicated that this carbohydrate binding was essential for NV/68 infectivity (15, 22). Nonsecretors did not develop any symptoms after challenge with NV/68. Furthermore, type O secretors were more likely to be infected with NV/68, while type B secretors were less likely to be infected with NV/68. In addition, epidemiological studies showed that some NoV strains could infect individuals with other ABH or secretor phenotypes, e.g., nonsecretors (29). Thus, NoVs form a group of viruses displaying different ABH and Lewis carbohydrate-binding profiles (11–14), and their host range is not limited to secretor individuals.

NoV VLP possesses a T = 3 icosahedral structure that comprises 180 VP1 monomers (44). Each VP1 has two major domains, a shell (S) domain, which forms the core of the icosahedral shell (2), and a protruding (P) domain, which forms arches extending from the shell. The P domain is located on the outermost surface of the viral particle and is responsible for host interactions (37, 38, 40–42). Recent crystallographic studies revealed that the P domain dimer forms a structure similar to that of the corresponding region of the VP1 protein, indicating that the P domain proteins are valid alternatives for ligand-binding studies (6). The P domain proteins lacking the N-terminal S domain are advantageous for use in structural studies compared with VLPs, because the P domain proteins are easily purified from extracts of transformed Escherichia coli cells and crystallographic analyses of them are conducted in a short period of time. The carbohydrate-binding site in the VA387 (GII/4) P dimer is predominantly formed by residues from two exposed loops that are close to the dimeric interface (3). In contrast, the carbohydrate-binding site in the NV/68 proteins is formed by the residues that project from a well-structured antiparallel β-sheet (6). Hence, although GI and GII S and P domains are organized similarly and although polypeptide folding in GI P domains is similar to that in GII P domains, the HBGA-binding site in the GI P domain is distinctly different from that of the GII P domain both in its location and structural characteristics (6).

Recently, the X-ray crystal structures of the P domains of GII NoVs in complex with Lewis antigens were reported (5, 9, 33). Structural analysis of the GII/4 variants showed that their strength of binding to Leb antigens was significantly altered because of the variability in the sequence GVVQDGSTTH396 (33). The VA207 (GII/9) P dimer primarily recognized α3Fuc of Ley and sialyl-Lex antigens, while GlcNAc of the core structure was poorly held by the protein (5). On the other hand, the P domain from the Vietnam026 strain (GII/10) was crystallized with Lea and Lex antigens, although these two Lewis antigens were not well defined in the crystal structures (9). We previously showed that GI/2, GI/3, GI/4, and GI/8 had great abilities to bind to the Lea antigen expressed by nonsecretors, a unique characteristic of GI that was not seen in GII (34). No GII strain bound strongly to the Lea antigen, although the GII/6 and GII/7 strains weakly bound to this antigen (34). However, the structural basis of the recognition for Lewis antigens by GI NoVs remains unknown. To understand how the Lea antigen interacts with the GI NoV VP1 protein, the P domain proteins from the Funabashi 258 (FUV258) strain (GI/2) were subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis and the crystal structures were resolved in complexes with Lea, Leb, H type 1, or A type 1 antigens at a resolution of ≈1.6 Å. The structures were compared with those of the NV/68 strain (GI/1), which does not bind to the Lea antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of enzymatically modified oligosaccharides.

p-Nitrophenyl type 1 carbohydrate chains were used throughout the experiment. As shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, GlcNAc-β1-O-p-nitrophenol was used as a starting material to prepare various enzymatically modified oligosaccharides (16). GlcNAc-β1-O-p-nitrophenol was modified by β1,3-galactosyltransferase V to obtain p-nitrophenyl type 1 disaccharide Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-O-p-nitrophenol. From this compound, p-nitrophenyl H type 1 antigen (H antigen) trisaccharide, p-nitrophenyl Lea trisaccharide, and p-nitrophenyl Leb tetrasaccharide were prepared by FUT1, FUT3, and both, respectively. p-Nitrophenyl H antigen trisaccharide was modified with the A enzyme (α1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase) or the B enzyme (α1,3-galactosyltransferase) to obtain p-nitrophenyl A type 1 antigen (A antigen) and B type 1 antigen (B antigen) tetrasaccharides, respectively. All synthesized products were subjected to reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a Cosmosil 5C18-AR column (4.6-mm inside diameter [i.d.] by 250 mm; Naikalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phases were 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid with 5% acetonitrile (solvent A) and 95% acetonitrile (solvent B). Each product was eluted with a linear gradient ranging from 0 to 30% solvent B in solvent A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min for 30 min at 40°C. The elution was monitored with an SPD-10AVP UV detector (absorbance at 210 nm; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

Bacterial expression of the wild-type and mutant FUV258 P domain proteins.

The DNA fragments encoding the FUV258 P domain with the hinge region (amino acids 221 to 541) were amplified by PCR using the forward primer 5′-TCTTGGGATCCGTCCCGCCTACCATAGAAGAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TATATAGCGGCCGCTTAAAGCCTACTTCTTGCCGT-3′. The amplified fragments were cloned into the BamHI and NotI sites of the pGEX-6P-2 vector (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) to generate the pGEX-258P plasmid. Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with pGEX-258P and grown in LB medium at 37°C. Protein expression was induced at 17°C with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested, resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) containing 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), and lysed by sonication. After removal of the debris, the lysate was subjected to a glutathione-Sepharose 4B gel (GE Healthcare). After a washing with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) was loaded, and the gel was incubated at 4°C overnight. The P domain dimer was purified by gel filtration with a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). Each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using rabbit antiserum raised against FUV258 VLPs. The collected P domain dimer was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and concentrated up to 10 mg of protein/ml. The protein concentration was determined by using a BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

The Q389N site-directed mutation at the α4Fuc-binding site was introduced by using the GeneTailor site-directed mutagenesis system (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The forward primer 5′-ACCATTGAATGGATTTCGAATCCATCTACA-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-AATCCATTCAATGGTGCCAATTGTAGTCACC-3′ were used to amplify the mutant P domain proteins. The Q389N mutant P domain proteins were expressed and purified in the same manner as the wild type.

Crystallization.

The purified P domain was crystallized by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. One microliter of protein solution (1% [wt/vol] protein in 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) was mixed with 1 μl of the reservoir solution containing 145 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.6), 5.8% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000), 4.3% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 16.5% (wt/vol) hexamethylene glycol and incubated at 20°C. Hexagonal bipyramid crystals 0.2 to 0.3 mm in length were formed in 4 to 7 days. For introducing oligosaccharides into the crystal, the crystal was soaked in a 10% (wt/vol) p-nitrophenyl–oligosaccharide solution, which was estimated to be at a concentration of >100 mM—a concentration typically used for soaking experiments—in a crystallization reservoir solution containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol as a cryoprotectant. After 30 min of incubation, the crystal was frozen with liquid nitrogen.

X-ray crystallography.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the BL5A, NW12A, and NE3A beamlines at the Photon Factory at KEK (Tsukuba, Japan) and processed by the HKL2000 program on the beamline (30). The statistics of the collected data are shown in Table 1. The Phaser program (24) from the CCP4 suite was used for phase determination by molecular replacement with the P domain of NV/68 (PDB:2zl7) as a model protein (31). Model building and refinement were carried out by the COOT (7) and REFMAC5 (25) programs from the CCP4 suite, respectively. The refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Structural figures were rendered by the PyMOL program (PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.2r1, 2010; Schrodinger LLC, New York, NY). The program Ligplot was used to draw a schematic diagram of sugar-protein interactions (43).

Table 1.

Data collection and structural refinement statisticsa

| Parameterb | Value for: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type |

Q389N mutant Leb (3ast) | ||||

| A (3asp) | H (3asq) | Lea (3asr) | Leb (3ass) | ||

| Data collection | |||||

| Resolution (outer shell) | 1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 1.40 (1.45–1.40) |

| Completeness (outer shell) | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) | 98.6 (99.8) | 99.9 (100.0) | 94.8 (98.2) |

| Mean I/sigma (outer shell) | 50.0 (4.68) | 57.3 (7.88) | 60.0 (3.29) | 79.0 (12.4) | 30.4 (10.4) |

| R-merge (outer shell) | 0.067 (0.687) | 0.080 (0.389) | 0.059 (0.478) | 0.043 (0.238) | 0.082 (0.173) |

| Wavelength | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| No. of reflections | 1,007,597 | 999,254 | 944,014 | 988,688 | 997,039 |

| No. of unique reflections | 88,006 | 88,182 | 88,689 | 88,556 | 131,683 |

| Refinement | |||||

| R-work/R-free | 18.2/20.2 | 17.8/19.3 | 20.0/21.7 | 18.4/20.1 | 19.7/21.2 |

| RMSDb from ideal values | |||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.05 |

| Rama plot (%) | |||||

| Favored | 99.5 | 99.3 | 98.9 | 99.5 | 99.0 |

| Allowed | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Outlier | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Avg B factors (Å2) (no. of atoms) | |||||

| Protein atoms | 17.16 (4,717) | 16.24 (4,727) | 26.00 (4,709) | 19.16 (4,722) | 15.2 (4,717) |

| Sodium atoms | 29.12 (2) | 26.92 (2) | 32.10 (2) | 28.51 (2) | 25.81 (2) |

| Sugar atoms | |||||

| p-Nitrophenol | 26.08 (20) | 47.95c (10) | 33.24 (20) | 28.05 (20) | |

| βGlcNAc | 36.63 (30) | 17.08 (28) | 39.16 (29) | 24.43 (28) | 18.85 (28) |

| β3Gal | 26.51 (22) | 13.92 (22) | 33.61 (22) | 21.23 (22) | 15.11 (22) |

| α4Fuc | 35.73 (20) | 22.91 (20) | 16.80 (20) | ||

| α2Fuc | 27.22 (20) | 14.54 (20) | 24.56 (20) | 16.88 (20) | |

| α3GalNAc | 16.89 (28) | ||||

| Water atoms | 26.44 (408) | 25.35 (411) | 38.64 (426) | 28.96 (385) | 28.85 (532) |

Cell data are as follows: space group, P31; number of molecules in the asymmetric unit, 2 (1 dimer); Vm, 2.55; dimensions (a [=b], c Å), 74.6, 107.0 (wild type) and 75.0, 107.3 (Q389N mutant).

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Modeled only in chain B.

Preparation of recombinant VLPs.

Tn5 cells, an insect cell line from Trichoplusia ni (Invitrogen), were grown at 27°C with Ex-CELL 400 (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS). VLPs were prepared by infecting subconfluent Tn5 cells with recombinant baculoviruses carrying the FUV258 VP1 gene, as described previously (36). Briefly, the culture media were harvested at 6 days after infection, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris, and further centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove baculoviruses. The VLPs in the supernatant were sedimented by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in an SW32 rotor (Beckman Instruments Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The pellet was resuspended in culture media containing 30% (wt/vol) CsCl and centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 20 h at 10°C in an SW55 rotor (Beckman). Peak fractions containing VLPs were pooled, diluted with culture media, and centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in an SW55 rotor. The VLPs were resuspended with culture media and used for experiments. The integrity of purified VLPs was confirmed by electron microscopy.

ELISA-based carbohydrate-binding assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based assays were used to detect and quantify NoV VLP attachment to HBGAs as described previously (34). Multivalent carbohydrate-biotin reagents conjugated to polyacrylamide (CHO-PAA-biotin; Glycotech, Rockville, MD) were rehydrated to 1 mg/ml with 0.3 M sodium phosphate buffer and diluted to 2.5 μg/ml with Tris-buffered saline. The carbohydrates (100 μl per well) were added to streptavidin-precoated plates (Thermo Electron Corporation, Vantaa, Finland) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The plates were then blocked with 300 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5) containing 5% skim milk (SM-PBS) overnight at 4°C. One hundred microliters of VLPs (1 μg/ml) in 5% SM-PBS was added, and plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The plates were washed 4 times with 300 μl of PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), 100 μl of the rabbit anti-rabbit NoV VLP antiserum (1:2,000 dilution) in 5% SM-PBS was added, and plates were incubated for 2 h at 3°C. After the wells were washed 4 times with PBS-T, 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) in 1% SM-PBS-T was added and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 3°C. The plates were washed 4 times with PBS-T, 100 μl of O-phenylenediamine (Sigma) was added as a substrate, and incubation proceeded at room temperature. After 30 min, 50 μl of 4 N H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction, and the optical density at 492 nm was measured.

PDB accession codes.

The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ) under the following codes: complex with the A antigen tetrasaccharide (A complex), 3asp; complex with the H antigen trisaccharide (H complex), 3asq; complex with the Lea trisaccharide (Lea complex), 3asr; complex with the Leb tetrasaccharide (Leb complex), 3ass; Leb complex of the Q389N mutant protein, 3ast.

RESULTS

Crystallization and structure determination.

The bacterially expressed FUV258 P domain dimer was purified to homogeneity and crystallized in a ligand-free form, as described in Materials and Methods. The crystals diffracted X rays up to 1.5-Å resolution. Cocrystallization was not successful; therefore, we conducted soaking experiments. Complexes of P domain dimers with each of five oligosaccharides, the H, A, B, Lea, and Leb antigens, were prepared by soaking the crystals in the respective oligosaccharide solutions. The deterioration in diffractability by the soaking was negligible. The crystal structures of the H, A, Lea, and Leb complexes were successfully obtained and modeled (Table 1). No interaction was observed to affect the crystal lattice. On the other hand, the complexes with the B antigen could not be modeled because the electron density of the carbohydrate chain was poorly mapped. These results were consistent with previous findings that FUV258 VLPs bound to H type 1, A, Lea, and Leb antigens but not to the B antigen (34). The Fo-F[r]c-omitt maps of the terminal Fuc and galactose (Gal) residues of each complex were clear at the 3.0-σ contour level, indicating that these residues were being discriminated from each other (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The remaining GlcNAcβ1-O-p-nitrophenol was identified at the 1.0-σ contour level or higher. The average B factors of the terminal Fuc and Gal residues were 35.7 and 33.6 Å2, respectively, which were comparable with that of the protein (26.0 Å2), suggesting a high degree of occupancy of the protein with the oligosaccharides. The average B factor of the GlcNAc moiety was 39.2 Å2, indicating less stability. However, the p-nitrophenol residues of the oligosaccharides tended to be disordered, probably because of the lack of a specific interaction with the protein molecules; the average B factor was 48.0 Å2. The p-nitrophenol residue was not modeled in the A complex (3asp) and in chain A of the Lea complex (3asr) (Table 1).

Overall structure of the P domain.

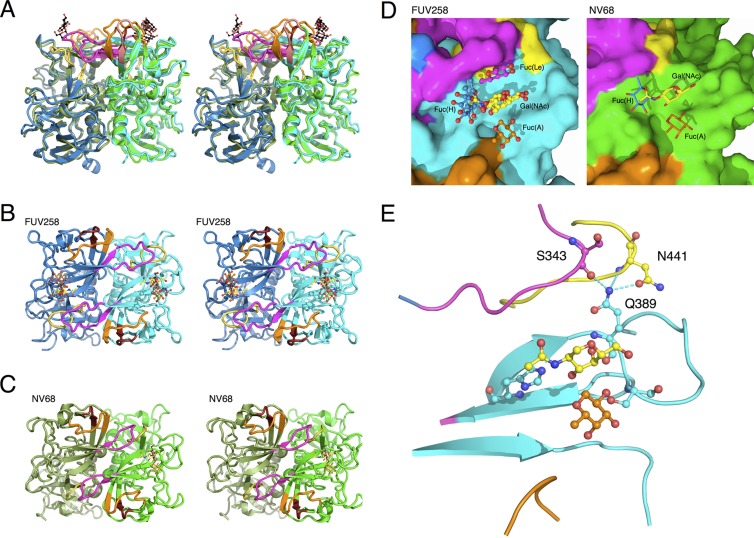

The overall structure of the P domain dimer of FUV258 was compared with that of NV/68 (6) (Fig. 1). The protein scaffold and the dimeric features of FUV258 are very similar to those of NV/68 (Fig. 1A to C), as predicted from the high degree of homology between the amino acid sequences. Both P domains comprise several β strands and one α helix (Fig. 1A to C) (6). However, the Cα atoms of the corresponding residues of the four loop structures, loop P, loop S, loop A, and loop B (magenta, yellow, orange, and brown, respectively, in Fig. 1A to C), continuously deviated by more than 2 Å in length. Significant differences were observed in particular between the loop P structures of the two strains, and these differences seem to reflect their biochemical roles. In the FUV258 P domain, loop P protrudes toward the next protomer and participates in forming a carbohydrate-binding site (Fig. 1D), suggesting that loop P directly contributes to carbohydrate binding and/or specificity (see below). The Gln389 residue located on the carbohydrate-binding site forms hydrogen bonds with the Ser343 residue in loop P of the other protomer and with the Asn441 residue in loop S of the same molecule, so that these two loops are fixed to antiparallel β-sheets on which the carbohydrate-binding site is constructed (Fig. 1E), suggesting that these interactions result in the elevated stability and integrity of the carbohydrate-binding site.

Fig 1.

Comparison of the crystal structures of the FUV258 and NV68 P domain dimers. (A) Superimposition of the structures of the two dimers. The structure of the A complex of the FUV258 dimer (blue) (PDB identification [ID]: 3asp) is superimposed onto that of the NV/68 dimer (green) (PDB ID: 2zl7). Chain A is shown in dark colors. The A antigen oligosaccharides in the FUV258 and NV/68 structures are depicted as ball-and-stick and stick models, respectively. (Note that an oligosaccharide on chain A of the NV/68 structure is absent.) The loops colored magenta (loop P) protrude toward the next protomer to form the Fuc(Le)-binding site. The loops colored yellow, orange, and brown and loop P lie next to each other. (B) Top view of the FUV258 A complex. The dimer is viewed from the top of the structure shown in panel A. GalNAc and Fuc(A), as a ball-and-stick model, are yellow and orange, respectively. (C) Top view of the NV/68 A complex. GalNAc and Fuc(A), as a stick model, are yellow and orange, respectively. (D) Close-up of the sugar-binding site on chain B of the FUV258 and NV/68 dimers. (Left) Binding site of the FUV258 P domain. The Gal moieties of the H, Lea, and Leb antigens and GalNAc of the A antigen are yellow. Fuc(A) of the A antigen, Fuc(H) of the H and Leb antigens, and Fuc(Le) of the Lea and Leb antigens are orange, blue, and magenta, respectively. (Right) Binding site of the NV/68 P domain. The same colors as for FUV258 are used for representing each saccharide moiety. (E) Fixation of loop regions by hydrogen bonds formed by the Gln389 residue. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds between Gln389 and Asn441 and between Gln389 and Ser343 of chain A.

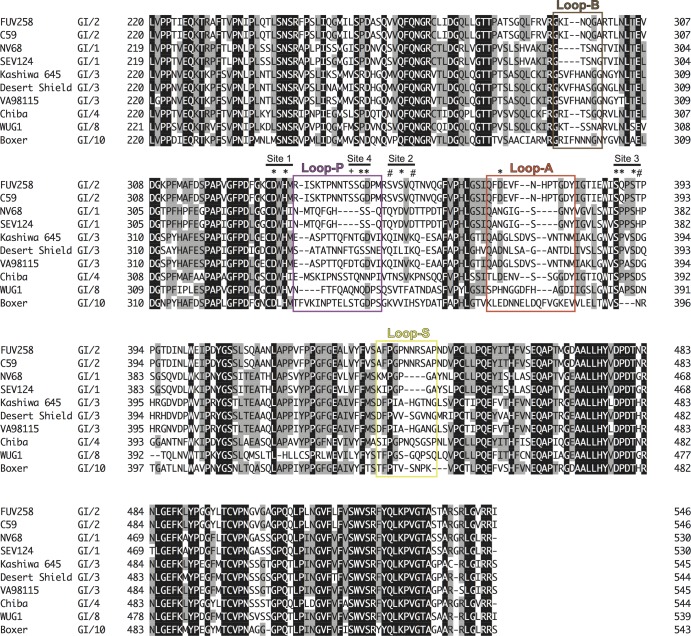

The sequence alignment of the P domains from various GI members is shown in Fig. 2. The overall amino acid sequences are similar, suggesting that they share a molecular architecture. Loop P is composed of almost identical numbers of amino acids in the GI/2 (FUV258), GI/3 (Kashiwa 645), and GI/4 (Chiba) strains but is remarkably short in the GI/1 (NV/68 and SEV124) and GI/8 (WUG1) strains (Fig. 2). We previously demonstrated that the GI/2 FUV258, GI/3 Kashiwa 645, and GI/4 Chiba VLPs had similar carbohydrate-binding profiles, since these three GI VLPs showed high levels of binding to saliva from type O, A, and AB secretors and nonsecretors. On the other hand, the GI/1 SEV124 and GI/8 WUG1 VLPs were found to be different from those of other GI strains in terms of their ability to bind saliva (34). GI/1 SEV124 bound efficiently to saliva from type O, A, and AB secretors but not to that from nonsecretors. Meanwhile, GI/8 WUG1 bound efficiently to not only O, A, and AB secretors and nonsecretors but also to B secretors. These results suggest that the difference in the length of the loop is related to the variation in specificity and affinity for HBGAs.

Fig 2.

Amino acid alignment of P domains from various GI strains. Boxed amino acid stretches correspond to the loop regions shown in Fig. 1. The amino acid sequences were aligned using GENETYX-MAC software (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The following strains were used for alignment: Funabashi 258 (FUV258; AB078335), C59 (AF435807), Southampton (L07418), Norwalk (NV68; M87661), Seto (SEV124; AB031013), Kashiwa 645 (BD011871), Desert Shield (U04469), VA98115 (AY038598), Chiba (AB042808), WUG1 (AB081723), and Boxer (AF538679). Letters with a black background indicate that the amino acids are conserved in all strains, whereas letters with a gray background indicate the amino acids appear in >50% of the strains. Amino acid residues with asterisks are found in the carbohydrate-binding sites in both the FUV258 and NV/68 P domains. Amino acid residues marked with a plus or number sign indicate the residues in the FUV258 or NV/68 P domains involved in the interaction with sugars, respectively. The carbohydrate-binding site is composed of subsites 1, 2, and 3 from the same protomer and subsite 4 from another protomer.

Carbohydrate-binding site.

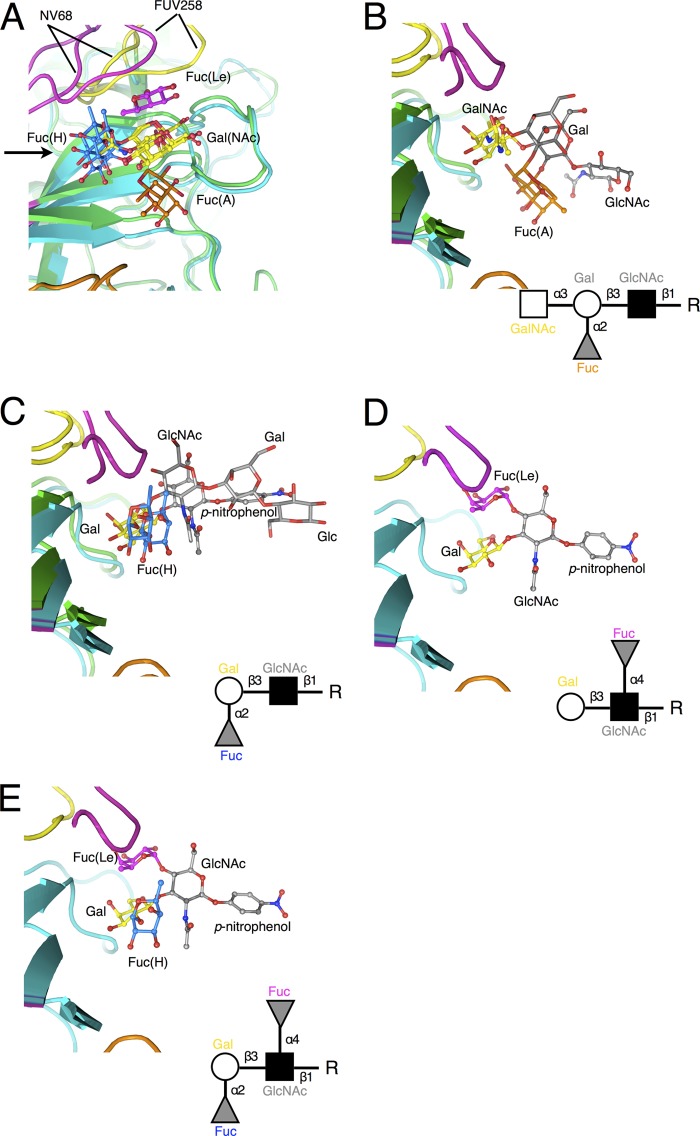

As shown in Fig. 3A, the carbohydrates used in this experiment were bound to the same position in the FUV258 P domain, which is identical to the NV/68 counterpart. No remarkable conformational changes upon carbohydrate binding (i.e., an induced fit mechanism on ligand recognition) between the free and bound forms (the coordinates of the ligand-free form of the FUV258 P dimer are not shown) were found. Notably, the terminal residues of the carbohydrate chains were preferentially recognized by the protein surface in an “end-on” rather than a “side-on” fashion. In the A complex (Fig. 3B), GalNAc and α2Fuc [Fuc(A)] at the nonreducing terminal interact with the protein and the distal Gal and GlcNAc (gray) are exposed to the solvent. The H, Lea, and Leb antigens are similarly placed on the P domain surface (Fig. 3C to E). Of note, although Galβ1-3GlcNAc is the base structure common to the four carbohydrates, the mode of binding of the A antigen appears to be different from that of the other three antigens. That is, the terminal GalNAc of the A antigen is overlaid on the Gal residues of the H, Lea, and Leb antigens, whereas the Gal of the A antigen does not interact with the P domain and is placed in the space where the GlcNAc of each of the other antigens is present, because an additional α3GalNAc residue is linked to the Gal of the base structure.

Fig 3.

Overviews of the interaction between the carbohydrate chains and the P domain. (A) Top view of the carbohydrate-binding site in chain B. The A, H, Lea, and Leb antigens bound to the FUV258 P domain (PDB IDs: 3asp, 3asq, 3asr, and 3ass) and the A and H antigens bound to the NV/68 P domain (PDB IDs: 2zl6 and 2zl7) are superimposed together with the protein backbones. For clarity, only the monosaccharides interacting with the P domain are shown. The colors used for Gal/GalNAc, Fuc(A), Fuc(H), Fuc(Le), and the proteins were as described for Fig. 1. An arrow indicates the viewpoint in panels B, C, D, and E. (B) Interaction of the A antigen with the FUV258 and NV/68 P domains. The A antigen in the FUV258 and NV/68 proteins is depicted as a ball-and-stick model (PDB ID: 3asp) and as a stick model (PDB ID: 2zl7), respectively. Note that the Gal moiety (gray) of the A antigen does not interact with the respective proteins. (C) Interaction of the H antigen with the FUV258 and NV/68 P domains. The H antigen in the FUV258 and NV/68 proteins is depicted as a ball-and-stick model (PDB ID: 3asq) and as a stick model (PDB ID: 2zl6), respectively. (D and E) Interaction of the Lewis antigens with the FUV258 P domain. The Fuc(Le) residues of the Lea (D) (PDB ID: 2asr) and Leb (E) (PDB ID: 2ass) antigens are in close proximity in loop P (magenta). The corresponding region of the NV/68 P domain is much shorter, as shown in panels B and C, suggesting that it cannot function in the recognition of Fuc(Le).

Meanwhile, the α4Fuc of the Lea and Leb antigens [Fuc(Le) in Fig. 3D and E] occupies a site different from those occupied by Fuc(A) and Fuc(H): it is in close proximity to loop P. Loop P may be an absolute determinant involved in the recognition of Lewis antigens, because the loop P of the NV/68 P domain is much shorter than that of FUV258 (Fig. 2), and therefore Fuc(Le) cannot be comfortably settled in the position corresponding to the Fuc(Le)-binding site in FUV258.

Galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-binding site.

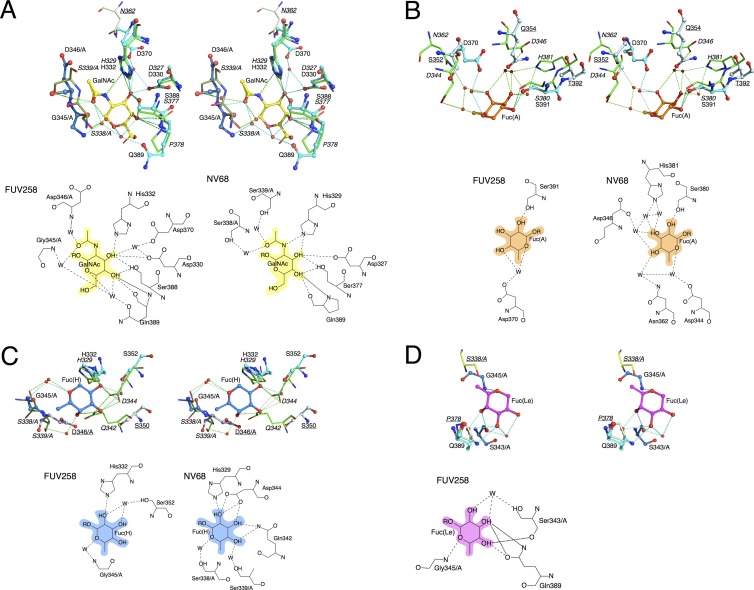

Similar regions in the P domains of both FUV258 and NV/68 are employed as the binding sites for the Gal residue of the H antigen and the GalNAc residue of the A antigen (Fig. 1D and 3B and C). As shown in Fig. 4A, the Asp330, His332, and Ser388 residues in the FUV258 P domain are involved in the interaction with the GalNAc moiety by forming hydrogen bonds with the O-3 and O-4 atoms (see the Ligplot diagram in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material for all interactions; the interactions of the sugar residues with the protein residues and the water molecules fixed by the protein are also listed in Table 2). The Gal of the H antigen is held by these three amino acid residues in a similar manner (data not shown). The corresponding residues (Asp327, His329, and Ser377) were also implicated in the carbohydrate binding in the P domain from NV/68 (Fig. 4A) (6). Since these three amino acids are conserved in the GI strains (Fig. 2), they play a common role in forming the Gal-binding site. Notably, for the FUV258 P domain, additional interactions of the Asp370 and Gln389 side chains via water molecules play a role in the binding of GalNAc (Table 2 and Fig. 4A), resulting in the increased affinity for these carbohydrates. Meanwhile, these interactions are not found in the NV/68 P domain. Indeed, we previously demonstrated that FUV258 VLPs had the ability to bind to a synthetic A disaccharide, GalNAcα1-3Galβ, while the SEV124 VLPs did not bind to it (34). The P2 domain of the SEV124 VP1 protein has 98% amino acid identity with the corresponding region of NV/68; different amino acids occupy positions 370 and 376 (Fig. 2). It is unlikely that these two amino acids are involved in HBGA binding (3, 4, 39).

Fig 4.

Stereoviews and schematic diagram of the interactions of each monosaccharide in the carbohydrate-binding sites. The binding sites in the FUV258 and NV/68 P domains are superimposed. The protein chains of the FUV258 protein are depicted in blue as a ball-and-stick model, while those of the NV/68 protein are depicted in green as a stick model. Each amino acid residue is represented by a one-letter code with the position number. Most of the residues are derived from chain B of the respective dimer. The residues from chain A are indicated by the suffix /A. The labels for the NV/68 proteins are italicized. The labels with underlining represent the residues that do not interact with either carbohydrates or water molecules. Dashed lines represent possible hydrogen bonds. The GalNAc moiety of the A antigen (A), the Fuc(A) moiety of the A antigen (B), the Fuc(H) moiety of the H antigen (C), and the Fuc(Le) moiety of the Lea antigen (D) are drawn. In the schematic drawings, the interactions occurring at greater than 3.3 Å are represented by dotted lines; these interactions are listed in Table 2 but not in the Ligplot diagram in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

Table 2.

Hydrogen bonds from monosaccharide to protein and waters fixed by protein

| Sugar | Atom | FUV258 |

NV/68 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (Å) | Atoma/residue no. or atom/water no. (distance [Å]) atom/residue no. | Distance (Å) | Atom/residue no. or atom/water no. (distance [Å]) atom/residue no. | ||

| GalNAc | H bonds to NGA1006 (chain B/3asp) | H bonds to NGA3 (chain B/2zl7) | |||

| O-3 | 3.17 | NE2/His332 | 3.13 | NE2/His329 | |

| 2.73 | OG/Ser388 | 2.88 | OG/Ser377 | ||

| 2.76 | OD2/Asp330 | 2.76 | OD2/Asp327 | ||

| 3.28 | O/water2220 (2.81) OD2/Asp330 and (2.65) OD2/Asp370 | ||||

| O-4 | 2.81 | OG/Ser388 | 2.72 | OG/Ser377 | |

| 2.58 | O/Gln389 | 2.62 | O/Pro378 | ||

| 3.49 | N/Gln389 | 3.45 | N/Pro378 | ||

| 3.04 | O/water2123 (2.79) OE1/Gln389 | ||||

| O-5 | 3.01 | O/water2123 (2.79) OE1/Gln389 | |||

| N-2 | 3.47 | NE2/His329 | |||

| O-7 | 2.75 | O/water2117 (2.79) N/Gly345/A | 2.71 | O/water569 (2.70) OG/Ser338/A | |

| 2.73 | O/water2281 (3.38) N/Asp346/A | 2.63 | O/water875 (3.29) OG/Ser339/A | ||

| Fuc(A) | H bonds to FUC1005 (chain B/3asp) | H bonds to FUC1 (chain B/2zl7) | |||

| O-2 | 2.58 | OG/Ser391 | 2.61 | OG/Ser380 | |

| O-3 | 2.43 | O/water1034 (3.41) NE2/His381 | |||

| 2.95 | O/water1030 (2.96) NE2/His381 | ||||

| 2.88 | O/water932 (3.00) OD2/Asp346 | ||||

| O-4 | 2.96 | O/water2309 (2.70) OD2/As;P370 | 3.41 | O/water932 (3.00) OD2/Asp346 | |

| 3.05 | O/water754 (2.96) ND2/Asn362 | ||||

| O-5 | 3.18 | O/water2309 (2.70) OD2/Asp370 | 2.90 | O/water833 (3.36) OD2/Asp344 | |

| Fuc(H) | H bonds to FUC1005 (chain B/3asq) | H bonds to FUC1 (chain B/2zl6) | |||

| O-2 | 3.04 | NE2/His332 | 3.06 | NE2/His329 | |

| 3.05 | OD2/Asp344 | ||||

| 3.17 | OD1/Asp344 | ||||

| 2.67 | O/water2208 (2.76) OG/Ser352 | ||||

| O-3 | 3.27 | O/water2208 (2.76) OG/Ser352 | 2.69 | OD2/Asp344 | |

| 3.29 | NE2/Gln342 | ||||

| O-4 | 3.13 | NE2/Gln342 | |||

| 2.62 | O/water877 (2.74) OG/Ser339/A | ||||

| O-5 | 2.89 | O/water2047 (2.88) N/Gly345/A | 2.79 | O/water551 (2.66) OG/Ser338/A | |

| Fuc(Le) | H bonds to FUC1004 (chain B/3asr) | ||||

| O-2 | 3.18 | O/water2051 (2.78) O/Ser343/A | |||

| O-3 | 2.87 | O/water2051 (2.78) O/Ser343/A | |||

| 3.34 | NE2/Gln389 | ||||

| 3.30 | OE1/Gln389 | ||||

| O-4 | 2.74 | OE1/Gln389 | |||

| 3.37 | O/Ser343/A | ||||

| O-5 | 3.04 | N/Gly345/A | |||

See the Ligplot diagram in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material for atom designations. The residues from chain A are indicated by the suffix /A.

α2-Fucose-binding sites.

As described above, three different Fuc-binding sites were found on the surface of the FUV258 P domain (Fig. 3A). These sites are for α2Fuc of the A antigen [Fuc(A)], α2Fuc of the H antigen [Fuc(H)], and α4Fuc of the Lea antigen [Fuc(Le)] (Fig. 3B to E). The side chain of Ser391 in the FUV258 P domain directly interacts with the O-2 atom of Fuc(A) (Fig. 4B and Table 2). As for the NV/68 P domain, Ser380, the counterpart of Ser391, plays the same role (6). However, the hydrogen bonds via water molecules are formed differently in the P domains from these two strains, suggesting that they alter the affinity for the A antigen. The SEV124 VLPs bound more efficiently to A trisaccharide than the FUV258 VLPs (Fig. 5), despite showing no ability to bind to A disaccharide, as described above. Fuc(H) is bound via a direct interaction with the side chain of the His332 residue in the FUV258 P domain (Fig. 4C and Table 2). On the other hand, in the NV/68 P domain, the side chains of Gln342 and Asp344 also participate in the interaction with Fuc(H), in addition to the corresponding His residue (His329). The Asp344 residue of the NV/68 P domain corresponds to the Ser352 residue in the FUV258 strain (Fig. 2), and these two residues occupy the same position (Fig. 4C). In the FUV258 P domain, Fuc(H) interacts with Ser352 via a water molecule (Fig. 4C), possibly because its side chain is shorter than that of the Asp residue. As in the case of Fuc(A), the numbers of hydrogen bonds are different between the two proteins (Table 2). This difference might reflect the different levels of binding of the H antigen to FUV258 and SEV124 VLPs (Fig. 5). However, it is difficult to compare these binding levels by means of an ELISA.

Fig 5.

Carbohydrate binding to VLPs. The binding of multivalent carbohydrate-biotin reagents conjugated to polyacrylamide to VLPs was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. VLPs were prepared from the culture media of insect cells after infection with recombinant baculoviruses carrying the Seto strain (SEV124; GI/1), the wild-type FUV258 strain, or the Q389N mutant of the FUV258 strain. The experiments were performed in duplicate and reproduced at least twice. Each data point represents the mean value with an error bar. The carbohydrate-biotin reagents are as follows: tri-H type 1, trisaccharide, including type 1 H antigen; tri-A, trisaccharide, including A antigen; tri-B, trisaccharide, including B antigen; Lea, trisaccharide, including Lea antigen; Leb, tetrasaccharide, including Leb antigen; biotin, biotin reagent without carbohydrates. OD, optical density.

α4-Fucose-binding sites.

Lea antigen has α4Fuc bound to GlcNAc differently from the A and H antigens, which have α2Fuc bound to the galactosyl residue. The VLP of FUV258 (GI/2) binds to the Lea antigen, whereas the VLPs of NV/68 and SEV124 (both GI/1) show no binding to this antigen (15, 34) (Fig. 5). To understand this difference in the VLPs of these viral strains, we examined the binding of the FUV258 P domain to the Lea antigen. As shown in Fig. 4D, the Gln389 residue makes a major contribution to the binding of Fuc(Le) of the Lea antigen. In addition, the backbone oxygen of Ser343 and the backbone nitrogen of Gly345 from another protomer also participate in the Fuc(Le) binding. Conversely, in the NV/68 P domain, the Pro378, which corresponds to Gln389 of the FUV258 protein, is unlikely to be able to contribute to forming a hydrogen bond. Moreover, the region corresponding to loop P, where Ser343 and Gly345 in the FUV258 protein are located, is much shorter in NV/68; therefore, the cavity that accommodates Fuc(Le), if such a cavity is present, is rather broad or is not properly formed.

Increased affinity to the Leb antigen due to the Q389N mutation.

Compared with that of the Lea and H antigens, the binding of the Leb antigen to the FUV258 VLP is much less efficient (Fig. 5). The crystal structure of the Leb complex of the FUV258 P domain suggests that the two Fuc residues are crammed into the respective binding sites; the side chain of the Gln389 residue in particular narrows the space that should accommodate the Fuc(Le) residue (Fig. 6A). Consequently, Fuc(H) is shifted toward Ser352; the favorable interactions between Fuc(H) and Ser352 found in the H complex (Fig. 6C) are broken in the Leb complex (Fig. 6A and Table 3). As described above, Gln389 is replaced with Pro in the NV/68 protein. Of note, despite the inability of the GI/1 protein to bind to the Lea antigen, it can bind to the Leb antigen (Fig. 5) (34). One possible explanation is that the Fuc(H) of the Leb antigen is bound by the GI/1 P domain, with the side chain of Pro378 not interfering with the Fuc(Le) of the antigen. It is possible that a decrease in the side chain volume of the amino acid residue at position 389 in the FUV258 P domain could improve the binding of the Leb antigen. To test this possibility, the Gln389 residue was replaced with Asn by means of site-directed mutagenesis and the Q389N mutant P domains were subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis. The mutation was found to significantly enhance the binding of the Leb antigen (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 6B and Table 3, the mutant FUV258 P domain comfortably accepts the Fuc(H) of the Leb antigen in a manner similar to that of the H antigen, concomitant with the binding to Fuc(Le) through the aid of water molecules. It should be noted that, in the Q389N protein, more amino acid residues participate in the formation of hydrogen bonds via water molecules to hold the two Fuc residues than in the wild-type protein (Table 3), which is consistent with the results of the ELISA-based carbohydrate binding of the Q389N mutant VLPs (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results suggest that loop P and the side chain of the amino acid residue at position 389 affect the carbohydrate binding. The crystal structures convincingly explain why the Q389N mutation changes the affinity for the two Lewis antigens.

Fig 6.

Differences between the wild-type and Q389N mutant FUV258 P domains in the interaction with Leb. The binding of the Leb antigen differs between the wild-type FUV258 P domain (A) (PDB ID: 3ass) and the Q389N mutant (B) (PDB ID: 3ast). Red dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds potentially responsible for carbohydrate binding. For comparison, the binding of the H antigen to the wild-type protein (ID: 3asq) is also shown (C).

Table 3.

Hydrogen bond interaction of Leb fucoses with the wild-type and Q389N mutant proteins

| Sugar | Atom | Wild type |

Q389N mutant |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | Atoma/residue no. or atom/water no. (distance) atom/residue no. | Distance | Atom/residue no. or atom/water no. (distance) atom/residue no. | ||

| Fuc(H) | H bonds to FUC1005 (chain B/3ass) | H bonds to FUC1005 (chain B/3ast) | |||

| O-2 | 3.09 | NE2/His332 | 3.16 | NE2/His332 | |

| 3.22 | OG/Ser352 | ||||

| 2.73 | O/water2256 (3.24) OD2/Asp370 | 2.81 | O/water2386 (2.71) OG/Ser352 | ||

| 3.30 | O/water2272 (3.24) OD2/Asp370 | ||||

| O-3 | 3.06 | O/water2386 (2.72) OG/Ser352 | |||

| 3.27 | O/water2210 (3.18) OD2/Asp346/A | ||||

| O-4 | 2.85 | O/water2210 (3.18) OD2/Asp346/A | |||

| Fuc(Le) | H bonds to FUC1004 (chain B/3ass) | H bonds to FUC1004 (chain B/3ast) | |||

| O-2 | 3.23 | O/water2136 (2.72) O/Ser343/A | 3.05 | O/water2331 (3.15) O/Ser343/A | |

| O-3 | 2.92 | O/water2136 (2.78) O/Ser343/A | 3.09 | O/water2322 (2.86) OD1/Asn441 and O/water2322 (2.74) O/Ser343/A | |

| 3.40 | NE2/Gln389 | 3.22 | ND2/Asn389 | ||

| 3.42 | OE1/Gln389 | ||||

| O-4 | 2.73 | OE1/Gln389 | 3.13 | O/water2322 (2.86) OD1/Asn441 and O/water2322 (2.74) O/Ser343/A | |

| 2.80 | O/water2315 (2.89) N/Asn389 and O/water2315 (2.89) O/Pro439 | ||||

| 3.29 | O/Ser343/A | 3.31 | O/Ser343/A | ||

| O-5 | 2.99 | N/Gly345/A | 3.20 | N/Gly345/A | |

See the Ligplot diagram in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material for atom designations. The residues from chain A are indicated by the suffix /A.

Differences in the recognition of the A and H antigens.

Although the FUV258 VLP recognizes and binds both the A and H antigens (Fig. 5), this recognition occurs differently for the two antigens. In the case of the H antigen, the Fuc(H)-Gal moiety is bound in the binding site (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, while the Fuc(H)-Gal moiety is included in the entire A antigen, the terminal GalNAc and α1-2-linked Fuc(A) moieties are recognized by the P domain in an “end-on” type of interaction (Fig. 3B). However, it is noteworthy that the GalNAc of the A antigen is overlaid with the Fucα1-2Gal of the H antigen and that a carbonyl oxygen of the N-acetyl group of GalNAc is placed at the same spatial location as the O-5 atom of Fuc(H) (Fig. 7). Moreover, two water molecules participate in the same manner in the formation of hydrogen bonds for the interaction between the P domain protein and the carbohydrate: W2117 and W2123 for the A antigen and W2074 and W2116 for the H antigen (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

The role of water molecules in the interactions of carbohydrates with the FUV258 P domain (stereoview). GalNAc and Fuc(A) are part of the A antigen (PDB ID: 3asp); Gal and Fuc(H) are components of the H antigen PDB ID: 3asq). Red dashed lines indicate possible water-mediated hydrogen bonds responsible for Fuc(H) binding.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the P domain protein from the NoV FUV258 strain that belongs to the GI/2 cluster was crystallized and soaked with the Lea, Leb, H, A, or B antigens and the structures were determined by X-ray crystallography at a high resolution of up to 1.6 Å, providing the structural basis for understanding how the Lewis antigen interacted with the GI VP1 protein. Our structural data confirmed that the FUV258 P domain bound to the Lea, Leb, H, and A antigens and indicated that a loop structure, loop P, played a critical role in the recognition of the Lea antigen. Loop P, together with neighboring loops, especially loop S, forms the Fuc(Le)-binding site. In addition, the Gln389 and Asn441 residues play an important role in the recognition of the carbohydrate and the formation of the carbohydrate-binding site. The amino acid residues Gly292, Thr293, Asn331, Thr333, Gln334, Phe335, His337, Ser338, Ser339, Gly363, Asn368, Gly429, and Ala430 (NV/68 numbering) in the P2 domain had already been predicted to be important for HBGA binding based on mutagenesis analyses and computer modeling (39), evolution trace analysis (4), and X-ray crystallographic analyses (3). It should be noted that these important amino acid residues were found on loop B, P, A, or S.

Mutation of the Gln389 residue dramatically affected the degree of binding of the Lewis antigens (Fig. 5). The crystal structures clearly indicated that, in the “Norwalk-type” Q389N mutant FUV258 P domain, the space that accommodated the Fuc(Le) moiety expanded much more than that in the wild type (Fig. 6A and B), which is consistent with the high-affinity binding of the Leb antigen to the Q389N mutant VLPs (Fig. 5). The Fuc(Le)-binding site does not overlap the Fuc(H) site. Therefore, the Leb antigen may be able to bind to the FUV258 P domain, in which the Fuc(Le) and Fuc(H) of this antigen simultaneously occupy the respective binding sites (Fig. 6A). However, a distortion in the Fuc(H) site appears to be present and to result in the low affinity of the wild-type P domain for the Leb antigen (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the binding pocket is insufficient to comfortably accommodate the Leb antigen (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, in the Q389N mutant P domain, the Leb antigen is fitted to the binding pocket in a relaxed, stabilized conformation (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, Fuc(H) of the Leb antigen in the mutant P domain is coordinated by water molecules in a similar manner to Fuc(H) of the H antigen in the wild-type protein, accompanied by flexible interactions at the Fuc(Le) site (Fig. 6C).

Concomitant with the Q389N mutation, slight movements of the Asn441 and Ser343/A residues (0.6 Å and 0.49 Å, respectively) were observed. Interestingly, the Gln389 in the wild-type protein directly interacts with Ser343/A in loop P (Fig. 1E), while the interaction between Asn389 and Ser343/A in the mutant protein is mediated via a water molecule (Fig. 6B). The presence of the water molecule consequently evokes the shift of Gly345 by 0.25 Å from the carbohydrate-binding pocket. It should be noted that Gly345 in loop P plays a critical role in the binding of both Fuc(H) and Fuc(Le). Moreover, in conjunction with the Q389N mutation, the loop region containing the residues from Ser391 to Thr396 moves away by up to 1.4 Å from the carbohydrate-binding pocket. Based on these results, it was concluded that the Q389N mutation expanded the space for Fuc(Le) and thus conferred an advantage in the binding of the Leb antigen. All or some of these slight movements in several regions evoked by the Q389N mutation might have been disadvantageous for the binding of the Lea antigen, resulting in a loose binding with a lowered affinity. By contrast, the Q389N mutant apparently lost its ability to bind to the A and H antigens (Fig. 5). Consistent with this result, we could not obtain models of the A and H complexes of the Q389N mutant P domain owing to the poor electron density map, strongly suggesting that the Q389N mutation perturbs a local structure around the carbohydrate-binding pocket.

The majority of GI NoVs interact with the A antigen but not the B antigen (34), despite their structural resemblance; the A antigen has a terminal GalNAc, whereas the B antigen has a Gal at the same position. As shown in Fig. 7, the carbonyl oxygen in the N-acetyl group of GalNAc of the A antigen interacts with the protein backbone via a water molecule. Similarly, a water molecule mediates the interaction between the protein and the O-5 atom of Fuc(H) of the H antigen. These features might help to explain why the B antigen is not recognized by the FUV258 VLPs (Fig. 5). Indeed, the P domain crystals soaked with the B antigen did not give sufficient electron density for the carbohydrates (data not shown). Here, we discuss two scenarios. (i) What would happen if the Fucα1-2Gal moiety of the B antigen is overlaid with Fuc(H)-Gal of the H antigen? Presumably the terminal α1-3-linked Gal of the B antigen interferes with the binding of the entire B antigen. (ii) What would happen if the terminal α1-3-linked Gal and Fuc(H) of the B antigen are overlaid with GalNAc and Fuc(H) of the A antigen, respectively? In this case, the only difference is whether the N-acetyl group or the hydroxyl group is linked to the second carbon of the Gal ring. As described above, the carbonyl oxygen in the N-acetyl group plays a crucial role in being recognized by the P domain. However, no atom is present at the equivalent position in the B antigen, resulting in a failure to form hydrogen bonds. The results of a previous study support our hypothesis (6). The authors suggested that the hydrophobic interaction with the N-acetyl group of GalNAc of the A antigen played a critical role in conferring NoV-HBGA binding specificity.

The evaluation of the hydrogen bonding interaction bridged by water molecules is complex because it is difficult to use computer programs to add and refine the hydrogen atoms around the sugar. This is a major future issue. (The calculations and evaluations are in progress.) On the other hand, the strong stacking interaction of the aromatic residues with the sugar chain that are typically found in the legume lectin was not found (44), although some hydrophobic contacts were seen (see Ligplot diagrams [43]) in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

Several X-ray crystallographic analyses were performed to investigate the structural basis for how HBGAs interact with the NoV capsid protein (3, 5, 6, 9, 33). The sites on HBGA for recognition by the prototype strain GI/1 NV/68 and the epidemic GII/4 variants have been analyzed in detail (3, 6, 33). They are situated at different locations on the protein surface. Consequently, GI and GII probably do not share a manner of Lea recognition. Therefore, to avoid ambiguous speculation, we do not describe the differences between GI and GII in this study.

The carbohydrates used in this study were bound to the same spaces of the FUV258 (GI/2) and NV/68 (GI/1) P domains. The VLPs of GI/1 and GI/2 strains share the common feature of showing a high level of binding to carbohydrates in the saliva of type O, A, and AB secretors but not to those in the saliva of type B secretors (34). However, the levels of binding to carbohydrates from nonsecretors differed between GI/1 and GI/2 (34). In the present study, we showed that the difference in the length and hence the structure of loop P between the two strains affected the degree of recognition of the Lewis antigens. A unique characteristic of several GI strains, such as GI/2, GI/3, and GI/4, is the ability to bind to the Lea antigen, which is not observed for any GII strains (34). The Lea antigen, which has a type 1 core structure, is the dominant antigen found in the secretions of nonsecretors. NoV binds to the gastroduodenal junction, and this binding is correlated with the presence of a type 1 core structure but not of a type 2 core structure (23). Moreover, an in vitro study showed that the type 1 carbohydrate binds more tightly to NoV VLPs than the type 2 carbohydrate (34). Overall, the differences in the amino acid sequences of the loop P region are potentially one of the determinants of whether the NoV strains of interest bind to the Lea antigen, and hence whether the strains infect nonsecretors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tatsuo Miyamura and Katsuo Natori (Department of Virology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan) for helpful discussions and for providing recombinant baculoviruses, respectively.

This work was supported by the R&D Project of Industrial Science and Technology Frontier Program supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization.

T.K. and H.S. conceived and designed the experiments. T.K., A.K., S.F., and H.S. performed the experiments. T.K. analyzed the data. H.I. provided synthetic carbohydrates. Y.S., N.T., and K.I. provided expert advice. T.W. and H.N. supervised the project. T.K., Y.S., N.T., and H.S. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2001. Diagnosis of noncultivatable gastroenteritis viruses, the human caliciviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:15–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, White LJ, Chen R, Venkataram Prasad BV, Estes MK. 2002. Structural requirements for the assembly of Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Virol. 76:4044–4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cao S, et al. 2007. Structural basis for the recognition of blood group trisaccharides by norovirus. J. Virol. 81:5949–5957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chakravarty S, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2005. Evolutionary trace residues in noroviruses: importance in receptor binding, antigenicity, virion assembly, and strain diversity. J. Virol. 79:554–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen Y, et al. Crystallography of a Lewis-binding norovirus, elucidation of strain-specificity to the polymorphic human histo-blood group antigens. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002152 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi JM, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Venkataram Prasad BV. 2008. Atomic resolution structural characterization of recognition of histo-blood group antigens by Norwalk virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9175–9180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Estes MK, et al. 1997. Virus-like particle vaccines for mucosal immunization. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 412:387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansman GS, et al. 2011. Crystal structures of GII.10 and GII.12 norovirus protruding domains in complex with histo-blood group antigens reveal details for a potential site of vulnerability. J. Virol. 85:6687–6701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansman GS, et al. 2006. Genetic and antigenic diversity among noroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 87:909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harrington PR, Lindesmith L, Yount B, Moe CL, Baric RS. 2002. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J. Virol. 76:12335–12343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrington PR, Vinjé J, Moe CL, Baric RS. 2004. Norovirus capture with histo-blood group antigens reveals novel virus-ligand interactions. J. Virol. 78:3035–3045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang P, et al. 2003. Noroviruses bind to human ABO, Lewis, and secretor histo-blood group antigens: identification of 4 distinct strain-specific patterns. J. Infect. Dis. 188:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang P, et al. 2005. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J. Virol. 79:6714–6722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hutson AM, Atmar RL, Graham DY, Estes MK. 2002. Norwalk virus infection and disease is associated with ABO histo-blood group type. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1335–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ito H, Chiba Y, Kameyama A, Sato T, Narimatsu H. 2010. In vitro and in vivo enzymatic syntheses and mass spectrometric database for N-glycans and O-glycans. Methods Enzymol. 478:127–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. 1993. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology 195:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kageyama T, et al. 2004. Coexistence of multiple genotypes, including newly identified genotypes, in outbreaks of gastroenteritis due to norovirus in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2988–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaneko M, et al. 1997. Wide variety of point mutations in the H gene of Bombay and para-Bombay individuals that inactivate H enzyme. Blood 90:839–849 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kapikian AZ. 1996. Overview of viral gastroenteritis. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 12:7–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kudo T, et al. 1996. Molecular genetic analysis of the human Lewis histo-blood group system. II. Secretor gene inactivation by a novel single missense mutation A385T in Japanese nonsecretor individuals. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9830–9837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindesmith L, et al. 2003. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat. Med. 9:548–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marionneau S, et al. 2002. Norwalk virus binds to histo-blood group antigens present on gastroduodenal epithelial cells of secretor individuals. Gastroenterology 122:1967–1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCoy AJ, et al. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40:658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nishihara S, et al. 1999. Molecular mechanisms of expression of Lewis b antigen and other type I Lewis antigens in human colorectal cancer. Glycobiology 9:607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nishihara S, et al. 1994. Molecular genetic analysis of the human Lewis histo-blood group system. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29271–29278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reference deleted.

- 29. Oriol R. 1990. Genetic control of the fucosylation of ABH precursor chains. Evidence for new epistatic interactions in different cells and tissues. J. Immunogenet. 17:235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. 2003. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reference deleted.

- 33. Shanker S, et al. 2011. Structural analysis of histo-blood group antigen binding specificity in a norovirus GII.4 epidemic variant: implications for epochal evolution. J. Virol. 85:8635–8645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shirato H, et al. 2008. Noroviruses distinguish between type 1 and type 2 histo-blood group antigens for binding. J. Virol. 82:10756–10767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shirato-Horikoshi H, Ogawa S, Wakita T, Takeda N, Hansman GS. 2007. Binding activity of norovirus and sapovirus to histo-blood group antigens. Arch. Virol. 152:457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tamura M, Natori K, Kobayashi M, Miyamura T, Takeda N. 2000. Interaction of recombinant Norwalk virus particles with the 105-kilodalton cellular binding protein, a candidate receptor molecule for virus attachment. J. Virol. 74:11589–11597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan M, et al. 2011. Terminal modifications of norovirus P domain resulted in a new type of subviral particles, the small P particles. Virology 410:345–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. 2004. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 78:6233–6242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tan M, et al. 2003. Mutations within the P2 domain of norovirus capsid affect binding to human histo-blood group antigens: evidence for a binding pocket. J. Virol. 77:12562–12571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan M, Jiang X. 2005. Norovirus and its histo-blood group antigen receptors: an answer to a historical puzzle. Trends Microbiol. 13:285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tan M, Jiang X. 2007. Norovirus-host interaction: implications for disease control and prevention. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 9:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan M, Jiang X. 2005. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 79:14017–14030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. 1995. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 8:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weis WI, Drickamer K. 1996. Structural basis of lectin-carbohydrate recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:441–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xi JN, Graham DY, Wang KN, Estes MK. 1990. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterization. Science 250:1580–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.