Abstract

During conjugation, a single strand of DNA is cleaved at the origin of transfer (oriT) by the plasmid-encoded relaxase. This strand is then unwound from its complement and transferred in the 5′-to-3′ direction, with the 3′ end likely extended by rolling-circle replication. The resulting, newly synthesized oriT must then be cleaved as well, prior to recircularization of the strand in the recipient. Evidence is presented here that the R1162 relaxase contains only a single nucleophile capable of cleaving at oriT, with another molecule therefore required to cleave at a second site. An assay functionally isolating this second cleavage shows that this reaction can take place in the donor cell. As a result, there is a flux of strands with free 3′ ends into the recipient. These ends are susceptible to degradation by exonuclease I. The degree of susceptibility is affected by the presence of an uncleaved oriT within the strand. A model is presented where these internal oriTs bind and trap the relaxase molecule covalently bound to the 5′ end of the incoming strand. Such a mechanism would result in the preferential degradation of transferred DNA that had not been properly cleaved in the donor.

INTRODUCTION

Plasmid DNA is transferred between cells during conjugation by a highly conserved mechanism. One of the DNA strands is first cleaved at a specific site, the origin of transfer (oriT), by a plasmid-encoded protein called the relaxase. Cleavage occurs by a transesterification, with a tyrosine residue forming a covalent phosphodiester linkage with the 5′ end of the cleaved strand. The relaxase is secreted into another cell by the type IV secretory pathway; the attached DNA strand is unwound from its complement and transported into the recipient as well, by some yet-unexplained mechanism. Although the initiating cleavage mechanism and the interaction of the relaxase with the secretory apparatus have been studied extensively, much less is known about how DNA transfer is terminated and how monomeric, circular molecules are then regenerated.

It is generally assumed that during conjugation, the 3′ end of the transferring strand is used as a primer for replacement strand synthesis in the donor. The multimeric intermediates that would result from such rolling-circle replication have been difficult to identify (12), but several observations support this idea. Relaxases that are members of several different protein families (16) have been purified, and all cleave single-stranded oriT oligonucleotides in vitro (11, 18, 31, 35). Plasmids containing two directly repeated oriTs (2xoriT plasmids) have been constructed with the idea that, when transfer is initiated at one, the other will act as a surrogate for the oriT formed by rolling-circle replication. For the mobilization system of the IncQ plasmid R1162 (RSF1010), the second oriT may be cleaved during transfer, with the resulting end then being able to join the 5′ end of the leading oriT. The requirements for cleavage at the trailing oriT are different from those for the initiating cleavage (24) and are consistent with the substrate being single-stranded (4). Recombination between directly repeated oriTs has also been observed for the plasmids R388 and R64, which are unrelated to R1162. Here, recombination occurs even in the absence of actual transfer; however, the structural requirements at each oriT are again distinct, and the reaction is stimulated if the substrate is locally unwound (6, 15).

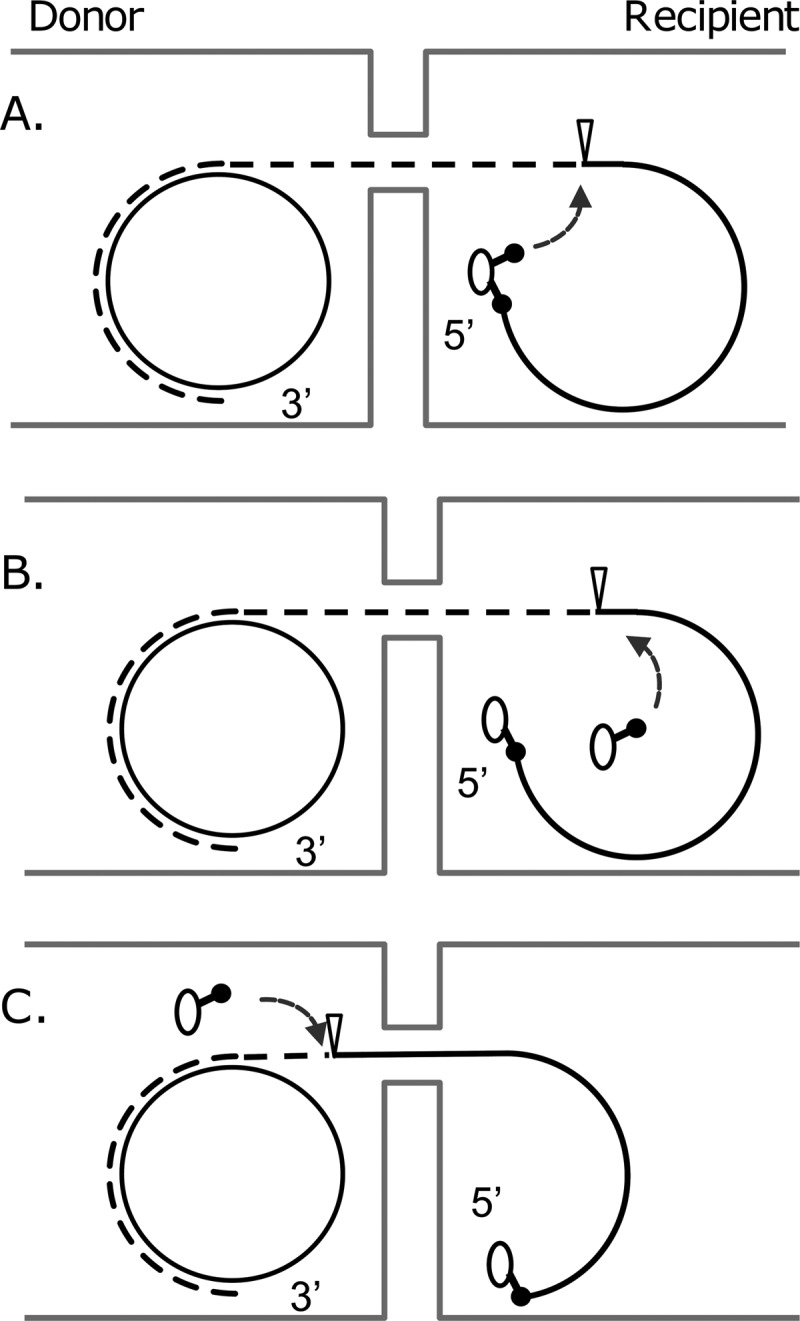

How and when is a trailing oriT, whether pre-existing as a second copy on the plasmid or generated by replication, cleaved during transfer? One possibility (Fig. 1A) is that the secreted relaxase, linked to the DNA, contains a second nucleophile that cleaves the trailing oriT. This arrangement is analogous to that of the Rep proteins of plasmids that replicate by the rolling-circle mode. The first nucleophile initiates replication by nicking the DNA, while the second nucleophile cleaves the extended strand at the trailing, newly formed origin of transfer. Alternatively, the relaxase could have only a single nucleophile, with the second cleavage being carried out by a different molecule of the protein. The second molecule could enter the recipient either as a dimer with the covalently linked relaxase (34) or as part of the general flux of DNA-free relaxases secreted by the donor (32) (Fig. 1B), or it could cleave the DNA strand in the donor before transfer (Fig. 1C). The relaxase TrwC of plasmid R388 contains two tyrosyl nucleophiles, and there is evidence that one (Y18) nicks within oriT to initiate cleavage while the other (Y26) cleaves the single-stranded trailing locus in the recipient cell (17–19). The relaxase domains of TrwC and the F factor protein TraI share 39% amino acid identity (26), and the structures, determined by X-ray crystallography, are very similar (20, 26). Interestingly, Y16 of TraI is active in nicking (10), but there is no evidence that Y23, which corresponds to Y26 in TrwC, is also a nucleophile active in transfer (11). Instead, it has been suggested that a second molecule of TraI acts in the donor to cleave the lagging oriT (11).

Fig 1.

Different possibilities for cleavage of a transferring strand extended by rolling-circle replication. The DNA synthesized during transfer is indicated by the dashed line, the cleavage site within oriT by the inverted triangle. The oval circle is the relaxase, and the stalked structure extending from it represents the nucleophilic amino acid active in cleaving the DNA.

The relaxases encoded by IncQ plasmids make up a very widely distributed family of relaxases (16), and although they are unrelated to the F family of relaxases on the basis of amino acid sequence, the regions of the proteins required for nicking at oriT have very similar structures (29). Only a single, nucleophilic tyrosine has been identified (35). Within or near the catalytic pocket, a second tyrosine and three glutamate residues, which could plausibly activate water for strand cleavage (30), were shown to be catalytically inactive (29). In the results described here, we provide evidence that the R1162 relaxase contains a single nucleophile, and that the 3′ end of the transferred strand can be generated in the donor cell. Because of this, single-stranded DNA molecules with free 3′ ends are transferred into the recipient during conjugal transfer. We show that these molecules are sensitive to exonuclease I, and that this sensitivity favors the recovery in the recipient of plasmids containing a single oriT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains are E. coli K-12. Derivatives of JC14450 and JC14450 xonA resistant to nalidixic acid were obtained by plating on medium containing 25 μg/ml of the antibiotic. Bacteria were grown in 1.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl supplemented as required with trimethoprim (200 μg/ml), ampicillin or Turboamp (Stratagene) (100 μg/ml), streptomycin sulfate (25 or 50 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol, kanamycin sulfate, or nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| MV10 | C600 ΔtrpE5 | 1, 22 |

| C600 Nalr | C600 derivative resistant to nalidixic acid | DF1019 in reference 14 |

| AB1157 | rpsL (Smr) | 1 |

| JC11450 | AB1157 Su- (spontaneous) | 21 |

| JC11450 Nalr | Resistant to nalidixic acid | This work |

| JC11450 xonA300::cat | Exonuclease I− | SMR839 in reference 21 |

| JC11450 xonA300::cat Nalr | Resistant to nalidixic acid | This work |

| AB1157 xonA xseA exoX | Exonuclease I−, exonuclease VII−, exonuclease X− | STL6127 in reference 13 |

The plasmids used for this work and their relevant properties are listed in Fig. 2. In addition, the general structure of the 2xoriT plasmids is shown in Fig. 3 (top). Details about the construction of plasmids not described elsewhere are provided in the supplemental material. The base sequences of the minimal R1162 and pSC101 oriTs and the oriT mutations discussed in this study are shown in Fig. 3 (bottom). The R1162 oriT was cloned as the fragment CCAGTTTCTCGAAGAGAAACCGGTAAATGCGCCCTCCCAT, with additional DNA containing the restriction sites for cloning. The pSC101 oriT was cloned either as the 132-bp fragment AGGGCGCACGTTTCTGAACGAAGTGAAGAAACGTCTAAGTGCGCCCTGATAAATAAAAGAGTTATCAGGGATTGTAGTGGGATTTGACCTCCTCTGCCATCATGAGCGTAATCATTCCGTTAGCATTCAGA (pUT1693, pUT2086 and pUT2087) or as the 50-bp fragment AGGGCGCACGTTTCTGAACGAAGTGAAGAAACGTCTAAGTGCGCCCTGAT (pUT2095).

Fig 2.

General properties of plasmids used in this study. Abbreviations: ApR, CmR, KmR, SuR, SmR, and TpR, resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, sulfonamides, streptomycin, and trimethoprim, respectively; IncP1β and IncQ1, incompatibility groups P1β and Q1; Rep(p15A) and Rep(pMB1), replication systems of indicated plasmids. The pSC101 oriT is designated oriTp, and the R1162 oriT is designated oriTr, with the direction of transfer being indicated by the arrow in the circle. The gene for the pSC101 relaxase is mobAp, and mobX::Km is the inactivated gene for the relaxosome accessory protein. The oriT mutations shown are those in Fig. 3. For plasmids containing two copies of oriT (2xoriT plasmids), “(1)” and “(2)” refer to the positions oriT(1) and oriT(2) described in the text and shown in Fig. 3 (top).

Fig 3.

(Top) General structure of the 2xoriT plasmids used in this study. The oriTs are oriented so that initiation of transfer at oriT(1) and termination at oriT(2) (arrow) results in deletion of lacO, which can be detected by plating cells on medium containing X-Gal. Termination of transfer at oriT(2) was also detected by the decrease in size of an EcoO109I-XmnI fragment. (Bottom) Base sequences of R1162 and pSC101 oriTs, showing the GTGT mutation and the ΔCCT deletion described in the text. The cleavage site is indicated by the inverted triangle: the relaxase forms a tyrosyl phosphodiester linkage with the 5′-terminal C residue.

Bacterial matings.

Except where indicated, the donor strains were all derivatives of MV10 (Table 1) containing the self-transmissible IncP1 plasmid R751 (23). Donor and recipient were grown overnight in selective medium, then diluted into fresh broth lacking antibiotics, and grown for 90 min. Mixtures consisting of 10 μl donor and 100 μl recipient were pelleted (ratio of donor to recipient cells, approximately 1:10), resuspended in 40 μl broth, and deposited on a broth agar plate. When the liquid spot had dried, the plates were incubated for 90 min at 37°C. An agar plug containing the cells was then placed in 1 ml broth, and the cells were washed into the medium by vortexing. The cells were plated at different dilutions on medium to select for transconjugants. In matings involving 2xoriT plasmids (Table 2), the recipient was C600 Nalr, and transconjugants were selected on medium containing Turboamp, nalidixic acid, and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (0.008%). On this medium, transconjugants containing unaltered 2xoriT plasmids form blue colonies, due to titration of the lac repressor by lacO on the plasmid. Plasmids formed by initiation of transfer at oriT(1) and termination at oriT(2) have lacO deleted (Fig. 3), and the transconjugant colonies are white (33). When the recipient was AB1157, JC11450, or a related strain (Table 3), donor cells contained pMS40 (28), an R1162 derivative encoding kanamycin resistance but lacking the streptomycin-resistance genes of the parental plasmid. The selective medium contained X-Gal, Turboamp, and either streptomycin (50 μg/ml) or nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml) when the nalidixic-acid-resistant derivatives were used. When plasmid DNA was subsequently extracted and analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4), medium for the selection of transconjugants als contained kanamycin. In all cases, donors were enumerated by plating on medium containing Turboamp alone. Data shown in Tables 2 and 3 are the results of at least three independent matings in each case. Mating frequencies were calculated as the number of transconjugants per donor cell. The frequency of initiation of transfer at oriT(1) and termination at oriT(2) (Fig. 3) was calculated as the number of white colonies divided by the total number of transconjugant colonies on the plates. Differences in the fraction of white colonies were tested for significance by a one-tailed t test, with a sample size of six independent matings for each condition. Calculations were performed at the VassarStat web site (vassarstats.net).

Table 2.

Transfer and termination frequency at oriT(2) for 2xoriT plasmidsa

| Mobilizing plasmid(s) | Relevant characteristic(s)b | 2xoriT plasmidc | oriT(1) | oriT(2) | Mobilization frequencyd | Termination frequency at oriT(2)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1162 | Mob(R1162) | pUT1297 | oriTr | oriTr(GTGT) | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.07 |

| pUT1682 | Mob(R1162) MobA(Q17ocr) | pUT1297 | oriTr | oriTr(GTGT) | 2.2 ± 0.3 × 10−3 | 0.41 ± 0.07 |

| pUT1621 | Mob(pSC101) | pUT1693 | oriTr | oriTp | 8.9 × 10−2 ± 3 × 10−2 | 0 |

| pUT1621 | Mob(pSC101) | pUT2086 | oriTr | oriTp(GTGT) | 9.6 × 10−4 ± 8.2 × 10−4 | 0 |

| pUT1621 | Mob(pSC101) | pUT2087 | oriTp | oriTp(GTGT) | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.05 |

| pUT2094 | Mob(pSC101) MobX::Km | pUT2086 | oriTr | oriTp(GTGT) | <1.1 × 10−8 ± 2 × 10−8 | – |

| pUT1682 | Mob(R1162) MobA(Q17ocr) | pUT2086 | oriTr | oriTp(GTGT) | 2.0 × 10−3 ± 0.7 × 10−3 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| pUT1682 + pUT2094 (donor) | Mob(R1162) MobA(Q17ocr) + Mob(pSC101) MobX::Km (donor) | pUT2086 | oriTr | oriTp(GTGT) | 1.4 × 10−3 ± 0.06 × 10−3 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| pUT1682 + pUT2094 (recipient) | Mob(R1162) MobA(Q17ocr) + Mob(pSC101) MobX::Km (recipient) | pUT2086 | oriTr | oriTp(GTGT) | 5.8 × 10−4 ± 0.2 × 10−4 | 0.24 ± 0.03 |

Table 3.

Effect of exonuclease I on termination frequency at oriT(2) for 2xoriT plasmids

| 2xoriT plasmid in donora | oriT(1) | oriT(2) | Recipient | Termination frequency | Recipient | Termination frequency at oriT(2)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pUT1619 | oriTr | oriTr | JC11450 | 0.52 ± 0.06 | JC11450 xonA | 0.23 ± 0.04 |

| pUT1619c | oriTr | oriTr | JC11450 Nalr | 0.51 ± 0.06 | JC11450 xonA Nalr | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| pUT1619 | oriTr | oriTr | AB1157 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | AB1157 xonA xseA exoX | 0.22 ± 0.00 |

| pUT1619 | oriTr | oriTr | JC11450 (+ pACYC184) | 0.42 ± 0.02 | JC11450 (+ pUT1984) | 0.66 ± 0.07 |

| pUT1619 | oriTr | oriTr | AB1157 xonA xseA exoX (+ pACYC184) | 0.22 ± 0.04 | AB1157 xonA xseA exoX (+ pUT1984) | 0.56 ± 0.02 |

| pUT1619d | oriTr | oriTr | JC11450 Nalr | 0.55 ± 0.04 | JC11450 xonA Nalr | 0.18 ± 0.00 |

| pUT1693 | oriTr | oriTpe | JC11450 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | JC11450 xonA | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| pUT2095 | oriTr | oriTpe | JC11450 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | JC11450 xonA | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

| pUT2096 | oriTr | oriTp(ΔCCT) | JC11450 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | JC11450 xonA | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

Donor strains also contained R751 and pMS40, except where indicated.

Fraction of transconjugants that were white on X-Gal.

Donor strain JC11450 xonA.

Donor strain contained pUT1682 instead of pMS40.

pUT1693, 132 bp pSC101 DNA; pUT2095, 50 bp pSC101 DNA.

Fig 4.

Relative amounts of the two plasmid types generated after transfer of the indicated 2xoriT plasmid. DNAs were extracted from pooled transconjugant cells after matings done in triplicate and digested with XmnI and EcoO109I, and the fragments were assayed by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The smaller fragment is derived from plasmids initiating transfer at oriT(1) and terminating at oriT(2); the larger fragment is derived from plasmids initiating and terminating at the same locus. In each panel, only the part of the gel containing the bands relevant for the analysis is shown.

Isolation and analysis of plasmid DNA from transconjugant colonies.

Each mating was carried out in triplicate as described above. Cells were scraped from a transconjugant plate containing more than 500 colonies, and the plasmid DNA was extracted by the Qiagen miniprep procedure. DNA samples were digested with XmnI and EcoO109I prior to electrophoresis through a 1.8% agarose gel. Sites for these enzymes flank the oriT(1)-lacO-oriT(2) region of the 2xoriT plasmids (Fig. 3). Digestion resulted in a characteristic fragment of known size for parental molecules and a smaller fragment for molecules from which lacO had been deleted due to termination of transfer at oriT(2). Additional fragments arising from the digestion also appeared on the gels in Fig. 4: for clarity these are not shown. The relative amounts of the large and small fragments shown in the gels were quantified by plotting and measuring areas under peaks with Image J software (9). Relative numbers of fragments were then calculated after correcting for the different fragment sizes.

Isolation and characterization of a MobA-oriT DNA covalent complex.

The R1162 relaxase MobA is a large protein with the oriT-processing domain located at the N-terminal third of the molecule. Purification of an N-terminal fragment active in binding and cleaving oriT has been described in detail elsewhere (3). To isolate the MobA-oriT DNA covalent complex that is formed following cleavage, streptavidin-coated magnetic particles (Promega) were prepared for use as described by the manufacturer. Approximately 0.6 mg beads was then mixed with 360 pmol of the 3′-biotinylated oligonucleotide GGCCAGTTTCTCGAAGAGAAACCGGTAAATGCGCCCTCCCCTACAAAGTAGGG (compare this with the R1162 oriT sequence [Fig. 3]) in a 600-μl final volume and then washed twice with the same volume of buffer W (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100). The beads and bound DNA were then washed twice and resuspended in a similar volume of low-salt MW buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 mM EDTA). For each reaction whose results are shown in Fig. 5, 100 μl of the bead preparation was first collected and resuspended in 200 μl MobA reaction buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 15% (vol/vol) glycerol] (35). The bound DNA was digested with approximately 2 μg (56 pmol) MobA relaxase fragment (MobA*) (3) for 40 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of EDTA to 50 mM with shaking for 5 min and then the addition of NaCl to 1 M. The salt removed any relaxase that was not covalently linked from the DNA. The beads were then washed five times with 400 μl buffer W and twice with 100 μl buffer MW, collected, and resuspended in 50 μl reaction buffer containing 0.7 pmol of the oligonucleotide CCAGTTTCTCGAAGAGAAACCGGTAAATGCCCCCTCCCTTTTGGGAATTC or CCAAGCTTCCCCCAGGATCCAGTTTCTCGAGAGAAACCGGTAAATGCG (designated oriT and oriT*, respectively, in Fig. 5). The oligonucleotides had previously been 5′-end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The samples were incubated for 1 h at 25°C. In some reactions (Fig. 5), MgCl2 was omitted from the buffer or 0.75 μg purified MobA fragment was added. Following incubation, the beads were heated to 90°C for 30 min and then collected, and the supernatant was saved for analysis by electrophoresis through a 12% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. Bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Fig 5.

Reaction of 5′-, 32P-labeled oligonucleotides oriT and oriT* (top) with free MobA and MobA covalently linked to cleaved oligonucleotide (cvc). Numbers are sizes of DNA in bases. Products were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide–8 M urea sequencing gel.

RESULTS

Evidence for a single nucleophile in R1162 MobA but a requirement for cleavage at oriT to terminate transfer.

The R1162 relaxase contains one nucleophile shown to be active in cleaving oriT DNA, the tyrosine at position 25 from the N-terminal end of the protein (counting the cleaved N-formyl methionine) (35). Inactivation of this nucleophile (Y25F substitution) causes a 100-fold decrease in the frequency of transfer (29). Other conserved residues, both within the active pocket of the enzyme and at other locations and potentially capable of functioning directly or indirectly as a second nucleophile, have been systematically mutagenized and shown not to inactivate transfer. These include the changes E38A, E74A, E76A, and Y32F, which were reported previously (29), as well as E43G, E65G, E82Q, and Y107F. Thus, we were unable to identify a second essential nucleophile by mutagenesis.

If the R1162 relaxase contains a second nucleophile active in transfer, then the protein, covalently linked to the 5′ end of cleaved oriT DNA, must be able to cleave as well a full-length, single-stranded oriT DNA. The 3′ end from this reaction would then form a phosphodiester linkage with the 5′ end of the DNA covalently linked to the relaxase, essentially a reversal of the initial nicking reaction. We have shown previously that MobA, covalently linked by a tyrosyl phosphodiester bond to the 5′ end of cleaved oriT DNA (and thus a presumed transfer intermediate), can bind a full-length oriT oligonucleotide (3). We have tested whether the covalent complex can also cleave this oligonucleotide at the correct location and then join the resulting 3′ end to the 5′ end of the covalently linked DNA. We isolated covalent complex on streptavidin beads (see Materials and Methods). The complex was then reacted with either full-length oriT oligonucleotide or oriT*, an oligonucleotide having the 3′ end that would be generated following cleavage by the relaxase. The results show that the complex was active for rejoining the covalently linked DNA to the preformed end but could not generate this end (Fig. 5, compare lanes 3 and 5). The reaction was magnesium dependent (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 6), as expected for the R1162 relaxase (36). As a positive control, free MobA was also added along with oriT (Fig. 5, lane 1). In this case, the complex joined to the newly generated ends created by the free enzyme, and in addition, cleaved oligonucleotide was generated. Thus, the oriT oligonucleotide could be cleaved, but not by the covalent complex. The free MobA did not prevent joining to oriT* (Fig. 5, lane 2); here, any cleavage product subsequently generated would be at the position of the starting, labeled substrate, and thus indistinguishable. These results do not rule out a cryptic nucleophile that is inactive under our conditions. However, if activation is required, it is not accomplished through some conformational change of the protein due to transesterification of the first nucleophile.

A single nucleophile would be sufficient if in fact there is no rolling-circle replication in the donor. In that case, the 3′ end of the initially cleaved oriT would be available for rejoining. A single base change (CAA→TAA) introduced a nonsense mutation early in the gene, at codon 17 (Q17ocr), causing a 2-log-unit decrease in transfer frequency (Table 2). We assume that the residual activity is due to misreading, since the small protein fragment translated up to the nonsense codon lacks the active tyrosine nucleophile (Y25) and would be unlikely to have any activity.

We used the R1162 derivative encoding MobA(Q17ocr) to mobilize a 2xoriT plasmid with the general structure shown in Fig. 3 (top). The 2xoriT plasmid was pUT1297 (Fig. 2), which contains the unmutated R1162 oriT (termed oriTr) at oriT(1) and a mutated R1162 oriT [termed oriTr(GTGT)] at oriT(2). The mutations, two C-to-T transitions at the cleavage site (Fig. 3, bottom), interfere with nicking of double-stranded oriT by the R1162 relaxosome (the complex of Mob proteins assembled at oriT) but not with cleavage and termination of transfer at a trailing oriT (24). Thus, transfer of this plasmid is overwhelmingly initiated at oriT(1) and terminated at either oriT(1) or oriT(2). When transfer is terminated at oriT(2), the resulting transconjugant is white on medium containing X-Gal because lacO has been deleted. Transfer of the complete plasmid results in blue colonies on this medium, due to titration of the lac repressor (33).

The frequency of termination at oriT(2) was unaffected by the Q17ocr mutation in mobA (compare R1162 and pUT1682 in Table 2). Mistranslation of a codon is rare, and we would expect the amount of active MobA to be low in cells containing the mutated mobA. Indeed, the 2xoriT plasmid and mutated R1162 are rarely cotransferred from the same cell in these cases (our unpublished data). As a result, if there were no strand extension from the 3′-OH generated by nicking, we would expect a much lower percentage of plasmids containing lacO deletions of R1162(Q17ocr) than the unmutated R1162, since a second molecule of MobA would generally not be available to cleave the trailing oriT. Because the lacO deletion frequency of pUT1297 is similar for both R1162 and R1162(Q17ocr), the likely interpretation is that oriT is extended by rolling-circle replication during transfer and must be cleaved prior to rejoining of the ends to form a circular plasmid in the transconjugant.

Generation of new 3′ ends in donor cells during transfer.

If a transferring DNA strand is extended from the 3′ end during transfer, how then is the resulting, newly generated oriT cleaved? Additional copies of R1162 MobA could do this either in the donor cell, where they are synthesized, or in the recipient cell, after secretion by the type IV pathway (Fig. 1) (32). We modified the 2xoriT plasmid system so that, as much as possible, initiation at oriT(1) and termination at oriT(2) would become functionally separate. This would allow us to assess the rate of termination at oriT(2), in the donor or recipient, under conditions where the overall initiation rate at each oriT is unaffected. To achieve this separation we used the pSC101 (8) Mob system, which is related to that of R1162, and used mutations like those previously isolated and characterized for R1162 Mob, with the expectation that they would behave similarly in the pSC101 system.

While the R1162 MobA is active on the pSC101 oriT (oriTp), the pSC101 relaxase does not recognize oriTr, the R1162 oriT (27). As a result, when the pSC101 Mob genes, cloned in the plasmid pUT1621 (Fig. 2) (27), were used to mobilize a 2xoriT plasmid (pUT1693) with oriTr at oriT(1) and oriTp at oriT(2), lacO was never deleted during transfer (Table 2), since transfer must be initiated at oriT(1) to generate the deletion (Fig. 3). We introduced into this oriTp the C-to-T transitions (Fig. 3) that, in R1162, specifically reduce the frequency of initiation of transfer without affecting termination (24). Mobilization of the resulting plasmid (pUT2086) by pUT1621 decreased about 2 log units, due to poor initiation from the mutated oriTp, and the frequency of lacO deletions remained at 0 (Table 2). However, when an unmutated oriTp was placed at oriT(1) to create the plasmid pUT2087, the deletion frequency was once again within the normal range (Table 2), indicating that the mutated oriTp was available for termination. Thus, the GTGT mutations have similar effects in both the R1162 and pSC101 Mob systems.

The pSC101 relaxosome consists of two proteins, the relaxase MobA and an accessory protein, MobX, both of which are required for assembly of the relaxosome and initiation of transfer (27). When MobX is inactivated to generate the plasmid pUT2094 (Fig. 2), pUT2086 was no longer transferred at a detectable frequency (Table 2), due to the combined effect of the C-to-T mutations in oriTp and the lack of a complete relaxosome. Because MobB, the R1162 protein analogous to MobX, is not required for termination of a 2xoriT plasmid by the MobA relaxase, we thought that the pSC101 MobA encoded by pUT2094 would still be able to terminate transfer at oriTp(GTGT), and, as shown below, this was the case.

In order to look at the rate of termination directly, we measured the recombination frequency of plasmid pUT2086 [oriTr at oriT(1) and oriTp(GTGT) at oriT(2)] under different conditions. When the mobilizing plasmid was pUT1682, the R1162 derivative encoding MobA(Q17ocr), the frequency of transfer was low, as expected, because there was little full-length MobA in the cell, but the transfer generated deletions because the protein was active for termination at the trailing oriTp(GTGT) (Table 2). We thought that since the amount of R1162 MobA in donor cells was low, we would be able to determine whether the pSC101 MobA is active in terminating transfer at oriTp(GTGT). When pUT2094 was present in addition to pUT2086 in donor cells, the recombination frequency increased significantly (Table 2) (P < 0.0001, n = 6). However, recombination was not stimulated when pUT2094 was in the recipient instead (Table 2). We conclude from this that the pSC101 MobA in donor cells can access and cleave a full-length, trailing oriTp(GTGT) during transfer. This access probably does not require any other Mob proteins, since the accessory proteins encoded by pUT1682 do not interact with the pSC101 MobA, and MobX was inactivated (27). The results indicate that 3′ ends of transferring strands can be generated in the donor and therefore that there must be a flux of such ends into the recipient during mating.

Sensitivity of DNA transfer to exonuclease I in the recipient.

If the DNA strands that enter a recipient cell during mating have free 3′ ends, then these might be subject to degradation by exonucleases I, VII, and X. These enzymes belong to redundant systems active in methyl-directed mismatch repair (5, 21, 38) and in the conservation of direct repeats by digestion of DNA strands following slippage during replication (13). Although the activities of these enzymes are largely overlapping in the context of repair, we focused on the effect of exonuclease I on transfer, since it is the best characterized.

We mobilized the 2xoriT plasmid pUT1619 (Fig. 2), which contains oriTr at oriT(1) and oriT(2), into JC11450 (AB1157 Su− [nonsuppressing derivative of AB1157]) and into the isogenic strain JC11450 xonA300::cat (21). Because these strains are resistant to streptomycin, the R1162 Mob proteins were provided in the donor by pMS40, a deletion derivative of R1162 (Fig. 2) encoding resistance to kanamycin but lacking the R1162 genes for streptomycin resistance. Transconjugants were selected for resistance to streptomycin and resistance to ampicillin (the latter encoded by pUT1619). The frequencies of mobilization of pUT1619 into all recipients were similar (data not shown), but inactivation of exonuclease I resulted in a smaller fraction of molecules terminating transfer at oriT(2) (Table 3). We also used JC11450 xonA as a donor, by mating into JC11450 and JC11450 xonA derivatives made resistant to nalidixic acid. Again, a lower fraction of transferred molecules terminated transfer at oriT(2) in the xonA recipient, while inactivation of exonuclease I in the donor had no effect (Table 3). When JC7623 (recB21 recC22 sbcB15) (25) was the recipient, a 2-fold decrease in the number of recombinants was again observed, compared to AB1157, the parental strain, as the recipient (not shown). The sbcB15 allele maps to xonA and results in less active exonuclease I in the cell (25). Thus, the effect of exonuclease I on termination was not allele specific. Finally, a triple deletion mutant (13) with exonucleases I, VII, and X inactivated showed no further change in the proportion of molecules with lacO deleted, beyond that caused by the absence of exonuclease I alone (Table 3).

To confirm the mating results, the fraction of pUT1619 molecules terminating at oriT(2) after transfer was also determined by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4). Donors containing pUT1619 were mated in triplicate with JC11450 and JC11450 xonA and plated on medium to select for transfer of pUT1619 and also pMS40, the cotransferred R1162 derivative providing the R1162 Mob proteins (see Materials and Methods). Cells were diluted so that there was a large number of transconjugants on the plates. Plasmid DNAs were then isolated from the pooled transconjugant colonies of each mating and analyzed by digestion with restriction enzymes and agarose gel electrophoresis. The results (Fig. 4) parallel the data obtained by plating: the proportion of molecules terminated at oriT(2), indicated by the relative intensities of the 921-bp and 1,223-bp bands on the gel, corrected for their size, varied according to whether exonuclease I was present. In the xonA strain, there were fewer recombinant molecules and a greater number of parental nonrecombinants.

The lower fraction of molecules terminated at oriT(2) in the xonA recipient is a direct effect of the lack of enzyme. When the recipient strain AB1157 xonA xseA exoX contained pUT1984, a plasmid with xonA under the control of the tet promoter in pACYC184 (7), the proportion of white transconjugants increased, relative to the strain containing the empty vector (Table 3). In addition, pUT1984 in the ExoI+ recipient JC11450 increased the fraction of white transconjugants to 0.66, which is significantly greater than the fraction obtained when the recipient contained the vector alone (P < 0.0001, n = 6). Thus, exonuclease I itself is actively affecting the proportion of molecules terminated at oriT(2) after transfer of pUT1619.

The effect of exonuclease I on termination was unaffected when the donor strain encoded the Q17ocr derivative of MobA (Table 3). Thus, the potential for multiple rounds of transfer into the same recipient, or the secretion of free molecules of relaxase into these recipients, did not affect sensitivity to exonuclease I as measured by the 2xoriT assay.

Reduced sensitivity of the pSC101 oriT to exonuclease I.

Since the R1162 Mob system is active on oriTp from the plasmid pSC101 (8, 27), we decided to test the effect of exonuclease I on termination when oriTp is at oriT(2). There is less base sequence homology between the oriTp and oriTr DNA fragments; if the effect of exonuclease I was still observed, it would further reduce the likelihood that regions of base sequence identity between the two oriTs are important for the generation of recombinants.

The 2xoriT plasmid pUT1693 contains a DNA fragment having 132 bp pSC101 DNA, including oriTp, at oriT(2) and the R1162 oriT (oriTr) at oriT(1) (Fig. 2). We first analyzed the termination frequency at oriT(2) by mating and then plating out for transconjugants on medium containing X-Gal, as described above. Compared to pUT1619, inactivation of exonuclease I in the recipient did not have as great an effect on the fraction of pUT1693 molecules terminating at oriT(2) during transfer (Table 3). A smaller fragment, containing 50 bp pSC101 DNA, again with the complete oriT, gave a similar result (pUT2095) (Table 3). However, when the pSC101 oriT contained a three-base deletion (oriTΔCCT) (Fig. 1), the effect of xonA on the termination frequency was restored (pUT2096) (Table 3). This difference was not an indirect effect of the mutation due to significantly different rates of initiation of transfer from oriT(2): R1162 mobilized plasmids containing only the pSC101 oriT and the deletion derivative at nearly identical frequencies (0.26 and 0.21 transconjugants per donor, each the average from two independent matings).

We also determined the fraction of molecules terminating at oriT(2) by using a gel analysis identical to that described for pUT1619 and shown in Fig. 4. As before, matings were carried out in triplicate for the analysis. The results (Fig. 4B and C) parallel those obtained by plating. Termination at oriT(2) was less affected by inactivation of exonuclease I when the 2xoriT plasmid contained the pSC101 oriT at this site. When oriT(2) contained the deletion, inactivation had a greater effect, causing a significant decrease in the fraction of transferred molecules terminated at oriT(2).

DISCUSSION

Together, our failure to identify a second nucleophile by mutagenesis and the inability of a MobA-oriT DNA covalent complex to cleave full-length oriT DNA in vitro (Fig. 5) indicate that the MobA relaxase contains only a single nucleophile active in transfer. However, decreasing the number of active MobA molecules in the cell, by introducing a nonsense mutation into the gene, did not affect the fraction of molecules initiating transfer at one oriT and terminating at another (Table 2). This suggests that two molecules of MobA are always required for transfer. One of these is required at initiation and the other at termination, to generate a free 3′ end at either the same or a second oriT. The implication is that transferring DNA is extended at the 3′ end of the cleaved oriT by rolling-circle replication.

We used a genetic approach to show that the second cleavage could occur in the donor cell (Table 2). This does not rule out cleavage at other points during transfer, or for that matter other mechanisms of cleavage. However, pUT2094, the plasmid responsible for increasing the second cleavage in the donor, did not support this cleavage in the recipient (Table 2).

The R1162 and pSC101 relaxases bind and cleave oriT DNA when it is single stranded, or at least when the helical DNA duplex has been disrupted (39). Therefore, in the donor cell an oriT is available for cleavage only during a defined window, from the time it is separated from its complementary strand to when it exits the donor through the conjugal pore. If molecules of relaxase are freely circulating in the cytoplasm, this constraint could put severe limits on the frequency of cleavage. One possibility is that replication and strand separation outrun transfer, so that loops of single-stranded DNA remain in the donor for some time before transfer. Another possibility is that relaxase molecules are concentrated at the transfer pore, where they can scan transferring DNA for oriT sites. Experiments to be presented elsewhere suggest that cleavage at a trailing oriT is carried out by relaxase molecules that are interacting to form a complex.

The 2xoriT plasmids rarely form recombinants at a frequency greater than 50% (Table 2). If oriT(2) accurately reflects the termination event during plasmid transfer, then we would expect that plasmid multimers might be detectable after transfer, particularly when mutations favoring their detection (such as recA in the recipient) are used. For R1162, plasmid forms arising due to skipped termination have been detected only after the introduction of oriT mutations favoring their appearance (12). Although the basic requirements for cleavage are likely to be the same, oriT(2) in the 2xoriT plasmid might not behave in termination in exactly the same way as the oriT generated de novo from the 3′ end of the initiating oriT. A possibly important difference is that the oriT(2) is not also the initiating oriT and is spatially separate from the initiating transfer complex. A complex of relaxases at the transfer pore could act as a mechanism for marking the oriT that initiates transfer and keeping track of the 3′ end. The results with the xonA recipient also suggest another possible reason for the failure to see multimers.

Cleavage at the trailing oriT in the donor cell means that during transfer DNA molecules with 3′ ends enter the recipient. These linear molecules would be potentially susceptible to degradation by exonuclease I. We did not see any large effect of exonuclease I on the transfer frequency. This is presumably because MobA, tethered to the 5′ end of the entering strand, rapidly binds to the trailing 3′ end and catalyzes recircularization of the DNA in the recipient. However, for transfer of the 2xoriT plasmid pUT1619, inactivation of xonA results in a smaller fraction of transconjugants containing plasmids that had terminated transfer at oriT(2) (Table 3). One way of explaining this observation, in view of our other results, is that full-length molecules of pUT1619 are more susceptible to exonuclease I during transfer and are thus diminished in the overall population of transconjugants, because they contain an internal copy of oriT. A relaxase covalently bound to the 5′ end of a strand can bind, but cannot cleave, a full-length single-stranded oriT (Fig. 5) (3). Such an oriT, present in the full-length transferring molecule as oriT(2), could therefore act as a decoy, binding the relaxase and increasing the exposure time of the 3′ end at oriT(1) to exonuclease I and therefore the likelihood that digestion will be initiated (Fig. 6). This would reduce the proportion of full-length plasmids in the transconjugant population. When exonuclease I is inactivated, selective degradation of the full-length DNA is eliminated, and its proportion increases in the transconjugants, with a corresponding decrease in the proportion of molecules terminated at oriT(2).

Fig 6.

Model for exonuclease I sensitivity of 2xoriT plasmid DNA. A full-length 2xoriT molecule that has just entered a cell by conjugation is shown at the top. The oriTs are represented by an inverted triangle, designating the cleavage site, and a loop indicating the inverted repeat (Fig. 3). The oval indicates a molecule of MobA covalently attached to the 5′ end of the entering strand. If this molecule binds to the free, 3′ end, as indicated by the arrow with the dashed line, then the ends of the DNA are rejoined and the full-length plasmid is regenerated (left). Alternatively, binding to the internal oriT(2) (right) exposes the 3′ end to degradation by exonuclease I.

MobA encoded by a plasmid in the recipient increased the termination rate at oriT(2) (pUT1984) (Table 3), indicating that free molecules of MobA can access the internal oriT of entering strands. For this reason, the plasmid decreased the decoy effect of oriT(2) in a xonA recipient (Table 3). In contrast, reducing the potential flux of free MobA into recipients, by using donors with the MobA Q17ocr mutation, had no effect on sensitivity to exonuclease I (Table 3). We conclude that free molecules of MobA do not bind significantly to the internal oriT during transfer, nor are they introduced into the recipient in sufficient concentrations to compete significantly with the covalently bound molecule for binding at oriT(2).

The apparent effect of oriT(2) as a decoy will be inversely related to its activity in cleavage and rejoining. If a high proportion of the molecules are cleaved at oriT(2) in the donor and then rejoined in the recipient, the proportion of molecules terminated at this locus will increase. As a result, there will be fewer full-length molecules entering the recipient, and the selective effect of exonuclease I will be diminished. When the pSC101 oriT, instead of the R1162 oriT, is at oriT(2), the fraction of recombinants is less affected by exonuclease I. The apparent resistance to exonuclease I is probably related to the different activities of these oriTs. The termination frequency for the pSC101 oriT was 0.37 in the absence of exonuclease I (pUT2095) (Table 3); this is greater than 0.23, the termination frequency for the R1162 oriT. If such values are regarded as being proportional to the “intrinsic” activity at oriT(2) in each case, then for the intact pSC101 oriT, a lower proportion of nonrecombinant forms were transferred. As a consequence, there were fewer of these molecules available to bind MobA and increase the chance of exonucleolytic degradation. When the ΔCCT deletion was introduced into the pSC101 oriT at oriT(2) (Table 3), the activity at this site decreased to 0.22, and sensitivity of full-length transferred DNA to exonuclease I increased (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

Sensitivity to exonuclease I might be one way of reconciling the apparently low frequency of cleavage at a trailing oriT (Table 2) with the difficulty of finding the multimers then expected from rolling-circle replication. If an oriT is “skipped” for cleavage during transfer, the distance between the internal oriT and a cleaved end would be at least one plasmid unit, not the length of the small lacO fragment used in these studies. The relaxase would be much more likely to find the internal oriT for binding than a cleaved oriT much further downstream in the direction of transfer. Such multimers would then be preferentially targeted for digestion by exonuclease I.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Lovett and S. Rosenberg for strains.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant GM37462.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bachmann BJ. 1972. Pedigrees of some mutant strains of Escherichia coli K-12. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:525–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barth PT, Grinter NJ. 1974. Comparison of the deoxyribonucleic acid molecular weights and homologies of plasmids conferring linked resistance to streptomycin and sulfonamides. J. Bacteriol. 120:618–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Becker EC, Meyer R. 2002. MobA, the DNA strand transferase of plasmid R1162. The minimal domain required for DNA processing at the origin of transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14575–14580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhattacharjee M, Rao XM, Meyer RJ. 1992. Role of the origin of transfer in termination of strand transfer during bacterial conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 174:6659–6665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burdett V, Baitinger C, Viswanathan M, Lovett S, Modrich P. 2001. In vivo requirement for RecJ, ExoVII, ExoI and ExoX in methyl-directed mismatch repair. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6765–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cesar CE, Llosa M. 2007. TrwC-mediated site-specific recombination is controlled by host factors altering local DNA topology. J. Bacteriol. 189:9037–9043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang ACY, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen S, Chang A. 1977. Revised interpretation of the origin of the pSC101 plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 132:734–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Collins T. 2007. ImageJ for microscopy. BioTechniques 43:S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Datta S, Larkin C, Schildbach J. 2003. Structural insights into single-stranded DNA binding and cleavage by F factor TraI. Structure 11:1369–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dostal L, Shao S, Schildbach JF. 2011. Tracking F plasmid TraI relaxase processing reactions provides insight into F plasmid transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:2658–2670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Erickson MJ, Meyer RJ. 1993. The origin of greater-than-unit-length plasmids generated during bacterial conjugation. Mol. Microbiol. 7:289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feschenko V, Rajman L, Lovett S. 2002. Stabilization of perfect and imperfect tandem repeats by single-strand DNA exonucleases. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1134–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Figurski D, Meyer R, Miller D, Helinski DR. 1976. Generation in vitro of deletions in the broad host range plasmid RK2 using phage Mu insertions and a restriction endonuclease. Gene 1:107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furuya N, Komano T. 2003. NikAB- or NikB-dependent intracellular recombination between tandemly repeated oriT sequences of plasmid R64 in plasmid or single-stranded phage vectors. J. Bacteriol. 185:3871–3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garcillan-Barcia M, Francia M, de la Cruz F. 2009. The diversity of conjugative relaxases and its application in plasmid classification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:657–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcillan-Barcia M, et al. 2007. Conjugative transfer can be inhibited by blocking relaxase activity within recipient cells with intrabodies. Mol. Microbiol. 63:404–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonzalez-Perez B, et al. 2007. Analysis of DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation by using suicide oligonucleotides. EMBO J. 26:3847–3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grandoso G, et al. 2000. Two active-site tyrosyl residues of protein TrwC act sequentially at the origin of transfer during plasmid R388. J. Mol. Biol. 295:1163–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guasch A, et al. 2003. Recognition and processing of the origin of transfer DNA by conjugative relaxase TrwC. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:1002–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harris R, Ross K, Lombardo M-J, Rosenberg S. 1998. Mismatch repair in Escherichia coli cells lacking single-strand exonucleases ExoI, ExoVII, and RecJ. J. Bacteriol. 180:989–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hershfield V, Boyer HW, Yanofsky C, Lovett MA, Helinski DR. 1974. Plasmid ColE1 as a molecular vehicle for cloning and amplification of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 71:3455–3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jobanputra RS, Datta N. 1974. Trimethoprim R factors in enterobacteria from clinical specimens. J. Med. Microbiol. 7:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim K, Meyer RJ. 1989. Unidirectional transfer of broad host-range plasmid R1162 during conjugative mobilization. Evidence for genetically distinct events at oriT. J. Mol. Biol. 208:501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kushner SR, Nagaishi H, Templin A, Clark A. 1971. Genetic recombination in Escherichia coli: the role of exonuclease I. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68:824–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larkin C, et al. 2005. Inter- and intramolecular determinants of the specificity of single-stranded DNA binding and cleavage by the F factor relaxase. Structure 13:1533–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meyer R. 2000. Identification of the mob genes of plasmid pSC101 and characterization of a hybrid pSC101-R1162 system for conjugal mobilization. J. Bacteriol. 182:4875–4881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meyer R, Hinds M, Brasch M. 1982. Properties of R1162, a broad-host-range, high-copy-number plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 150:552–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monzingo A, Ozburn A, Xia S, Meyer R, Robertus J. 2007. The structure of the minimal relaxase domain of MobA at 2.1 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 366:165–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noirot-Gros M, Bidnenko V, Ehrlich S. 1994. Active site of the replication protein of the rolling circle plasmid pC194. EMBO J. 13:4412–4420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pansegrau W, Schroder W, Lanka E. 1993. Relaxase (TraI) of the IncPa plasmid RP4 catalyzes a site-specific cleaving-joining reaction of single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:2925–2929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parker C, Meyer R. 2007. The R1162 primase/relaxase contains two, type IV transport signals that require the small plasmid protein MobB. Mol. Microbiol. 66:252–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rao XM, Meyer RJ. 1994. Conjugal mobilization of plasmid DNA: termination frequency at the origin of transfer of plasmid R1162. J. Bacteriol. 176:5958–5961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rasooly A, Wang P-Z, Novick R. 1994. Replication-specific conversion of the Staphylococcus aureus pT181 initiator protein from an active homodimer to an inactive heterodimer. EMBO J. 13:5245–5251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scherzinger E, Kruft V, Otto S. 1993. Purification of the large mobilization protein of plasmid RSF1010 and characterization of its site-specific DNA-cleaving/DNA-joining activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 217:929–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Otto S, Dobrinski B. 1992. In vitro cleavage of double- and single-stranded DNA by plasmid RSF1010-encoded mobilization proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:41–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thorsted P, et al. 1998. Complete sequence of the IncPβ plasmid R751: implications for evolution and organization of the IncP backbone. J. Mol. Biol. 282:969–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viswanathan M, Burdett V, Baitlinger C, Modrich P, Lovett S. 2001. Redundant exonuclease involvement in Escherichia coli methyl-directed mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem. 276:31053–31058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang S, Meyer RJ. 1995. Localized denaturation of oriT DNA within relaxosomes of the broad host-range plasmid R1162. Mol. Microbiol. 17:727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.