Abstract

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is the first of the human herpesviruses to be attenuated and subsequently approved as a live vaccine to prevent varicella and herpes zoster. Both the attenuated VZV vaccine, called vaccine Oka or vOka, and the parental strain pOka have been completely sequenced. Yet the specific determinants of attenuation are uncertain. The open reading frame (ORF) with the most single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), ORF62, encodes the regulatory protein IE62, but IE62 studies have failed to define a specific SNP associated with attenuation. We have completed next-generation sequencing of the VZV Ellen genome, a strain known to be highly attenuated by its very limited replication in human skin xenografts in the SCID mouse model of VZV pathogenesis. A comparative analysis of the Ellen sequence with all other complete VZV sequences was extremely informative. In particular, an unexpected finding was a stop codon mutation in Ellen ORF0 (herpes simplex virus UL56 homolog) identical to one found in vOka, combined with the absence of polymorphisms in most Ellen ORFs that were known to be mutated in vOka. The mutated ORF0 protein was also imaged in both two dimensions and three dimensions by confocal microscopy. The probability of two VZV strains not connected by a recent common ancestor having an identical ORF0 SNP by chance would be 1 × 10−8, in other words, extremely unlikely. Taken together, these bioinformatics analyses strongly suggest that the stop codon ORF0 SNP is one of the determinants of the attenuation genotype of live VZV vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Varicella (chickenpox) is a common infection of children around the world. The disease is caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a human herpesvirus (35). Because of the morbidity associated with VZV infection of children, the live attenuated varicella vaccine called VZV-Oka was developed after serial passaging in cultured cells by M. Takahashi in the 1970s (33). Currently, this live attenuated vaccine is administered to millions of children annually in countries around the world (11). A subsequent reformulation of the live attenuated varicella vaccine with 14 times more infectious virus was shown to be effective at preventing zoster (shingles); this vaccine is now recommended for all older adults in the United States (24).

The goal of this research project is to define determinants of VZV attenuation. In 2002, the entire VZV Oka genome of the vaccine strain (vOka), as well as that of its parent (pOka), was sequenced (12). The prototype VZV Dumas had previously been sequenced in 1986 (6). Shortly after publication of these sequences plus an additional 11 whole-genome VZV sequences, there were attempts to define the determinants of attenuation (15, 26, 34). The largest number of SNPs in vOka were found in the viral regulatory gene called open reading frame 62 (ORF62); the IE62 protein is the homolog of herpes simplex virus (HSV) ICP4. However, in vitro analyses of IE62 and its functional domains have failed to define even one or two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or as critical determinants of altered VZV replication in vitro (5, 36).

While it has been proposed that VZV vaccine attenuation is the result of a set of mutations within the vOka genome, the genetic basis of reduced virulence is not yet known. Otherwise stated, there is no precise enumeration of the attenuation SNPs. In this report, we readdress the issue of VZV attenuation by a bioinformatics approach, which was dependent upon the whole-genome sequencing of an additional laboratory VZV strain called VZV Ellen (3). This strain, which was first described in 1964, is known to have become highly attenuated after at least 90 passages in cultured cells. The severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model of VZV pathogenesis provides the only animal model that allows an assessment of VZV virulence in intact human tissues infected in vivo (1). For example, infection of human skin xenografts with vOka leads to minimal replication compared to infection with the parental strain pOka (21). In the same set of experiments in the SCID-hu mouse model, we demonstrated that infection with VZV Ellen is even more highly attenuated.

When the complete Ellen sequence was analyzed, we noted two common SNPs in ORF62 shared with vOka sequence. Even more surprising, we noted that VZV Ellen had exactly the same mutation in ORF0 as the vaccine strain, while lacking other shared polymorphisms with vOka (17, 20). This ORF had been overlooked in the original 1986 publication of the Dumas sequence and has not been considered a prime candidate for the attenuation phenotype. Based on studies carried out with the HSV-2 homolog UL56, one property of this protein includes trafficking of virus within the infected cell (19). The ORF0 protein may also be involved in viral replication (16). After a review of the latest VZV genomic data, including the publication of the genomic sequence of a second live attenuated varicella vaccine, we propose that a stop codon mutation in ORF0 is one of the determinants of the attenuation genotype in the varicella and zoster vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The VZV Ellen strain was obtained from the ATCC in the 1990s, but the virus was originally isolated from a child with varicella in Atlanta, GA, in 1964 (3). The LAX1 strain was isolated from a child with varicella in Los Angeles, CA, in the 1990s. The sequences of 6 of its 70 genes were reported in 2001 (10). The VZV-32 strain is a common laboratory strain that has been sequenced previously (26). Based on a decision reached at a common VZV nomenclature meeting held in 2008, VZV strains named before 2008 will retain their original name (2).

Next-generation sequencing.

Prior VZV genome sequencing technology has been described previously (26). For the current project, replicating preparations of viral DNA were prepared, and genomes were sequenced using Genome Sequencer (GS) FLX Titanium high-throughput pyrosequencing technology (Roche/454 Life Sciences) (8, 30). Rapid libraries using multiplex identifiers (MIDs) were created for both VZV Ellen and VZV LAX1, following the Rapid Library Preparation Method per the manufacturer's instructions (Roche/454 Life Sciences)(8, 30). After quantitation via fluorometry, small-volume emulsion PCRs (SV emPCRs) were carried out on the libraries, followed by enrichment of the amplified DNA beads per the manufacturer's instructions. The enriched DNA beads were run on one-fourth of a picotiter plate (PTP) during a GS FLX Titanium sequencing run. The parsed sequencing data obtained for each viral genome was assembled using the gsAssembler software (Roche/454 Life Sciences), resulting in four contigs for each of the two strains. The gaps between the contigs, as well as a number of variable-length homopolymer regions which are poorly resolved through the nature of pyrosequencing, were amplified by PCR and sequenced with standard Sanger sequencing technology in order to elucidate the full genomic DNA sequences.

Imaging protocols.

Samples of infected and uninfected cells were processed for confocal microscopy by methods described previously (4). Following preparation, the samples were viewed on Zeiss 510 and 710 confocal fluorescence microscopes (9). In addition, the three-dimensional (3D) structures of VZV-infected cells were reconstructed from Z-stacks of confocal laser scanning microscopic images using Imaris software, version 7.5 (Bitplane Scientific Software) (27). Properties of antibody reagents against VZV proteins ORF0, gE, gC, and IE62 have also been described previously (20, 31).

Real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from uninfected and VZV-infected MRC-5 fibroblast cells in six-well plates at the given time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 hpi) using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Polyadenylated RNA was converted to cDNA using anchored oligo(dT) primers and a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) for first-strand synthesis. Real-time PCR was performed using Power SYBR green PCR Master Mix (ABI). Primers for amplification of ORF0, VZV gE, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) included the following: ORF0 forward, 5′-TCT TGT TTG AAC GAC GAG TGG CGA-3′; ORF0 reverse, 5′-AGG TGT TCG GGA ATC TGA TAG CGA-3′; gE forward, 5′-CCC CGT AAA CCC CGG AAC GT-3′; gE reverse, 5′-CCC GTG ACT CCC TCC AAT CGC-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-CGA CCA CTT TGT CAA GCT CA-3′; and GAPDH reverse, 5′-AGG GGT CTA CAT GGC AAC TG-3′. Primers for gC (ORF14) have been published previously (31). Triplicates of infected cell samples were amplified with the respective primers to generate amplification curves, which were processed using SDS, version 1.2.3, software (Applied Biosystems). Threshold cycle (CT) values of the GAPDH amplifications at each time point were normalized to a constant value (9.0). The resulting normalization was then applied to the ORF0 and gE CT values. In effect, this is a correction for different amounts of total cDNA due to different amounts of cells in each sample or slight loading errors. The relative concentration of mRNA between VZV ORF0 and gE was then computed as 2(CT − CT(0)), where CT(0) was set to 12 arbitrarily.

Radioimmunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE.

VZV-infected cultures were radiolabeled with [35S]methionine-cysteine (PerkinElmer) at 24 h postinfection (hpi) and harvested at 48 hpi to prepare antigen for immunoprecipitation. These methods, as well as those for SDS-PAGE, have been previously published (13, 23).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences were deposited in GenBank. VZV Ellen has accession number JQ972913, and VZV LAX1 has number JQ972914.

RESULTS

The complete sequence of VZV Ellen and clade-specific polymorphisms.

The total number of Ellen nucleotides was 124,783. By comparison, VZV Dumas contains 124,884; the Oka parent strain contains 125,125; and the Oka vaccine strain contains 125,078. The differences between VZV Ellen and VZV Dumas were first assessed because these two VZV strains belong to different European VZV clades. Therefore, there are clade-specific polymorphisms that are not expected to be associated with attenuation. VZV Dumas (clade 1) is the prototype sequence upon which all SNPs are assigned. VZV Ellen is a member of clade 3.

Altogether, there were 29 notable differences between Ellen and Dumas sequences (Table 1). These differences included both insertions/deletions (indels) and SNPs. In our initial analysis of VZV clades in 2006 and 2007, we defined SNPs specific to clade 3 (formerly called clade D). Subsequently, at the VZV common nomenclature meeting in 2008, further SNPs were selected to represent the different clades. Clade-specific polymorphisms relative to the Dumas sequence were observed in the following Ellen ORFs: 2, 5, 6, 7, 11, 22, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 62, and 68 (Table 1). Coding mutations were observed in ORFs 2, 5, 6, 7, 11, 35, 37, 38, 43, 62, and 68. Of considerable interest, a TAT insertion was detected between ORF39 and ORF40; this same insertion has been seen in only one previously sequenced VZV genome, namely, the VZV 22 strain from Canada, which happens to be another member of clade 3. Therefore, we included the indel in Table 1.

Table 1.

Polymorphisms in the genome of VZV Ellen specific to clade 3 of the VZV phylogenetic treea

| Reference sequence position (nt) | Nucleotide change | ORF | Amino acid | Ellen sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 | A/C | ORF2 | M238 | M238L |

| 2596 | T/C | Inter | NA | X |

| 2643 | G/A | Inter | NA | X |

| 4402 | G/A | ORF5 | C291 | Syn |

| 5827 | C/A | ORF6 | V917 | Syn |

| 9243 | G/A | ORF7 | E213 | E213K |

| 15896 | G/T | ORF11 | E769 | E769D |

| 35141 | C/T | ORF22 | G353 | Syn |

| 64191 | G/A | ORF35 | P188 | P188L |

| 66112 | T/G | ORF37 | L13 | Syn |

| 66288 | G/A | ORF37 | R72 | R72K |

| 68101 | T/C | ORF37 | P676 | Syn |

| 68254 | C/T | ORF37 | C727 | Syn |

| 69424 | G/A | ORF38 | D290 | Syn |

| 70014 | C/A | ORF38 | A94 | A94S |

| 71196 | C/T | ORF39 | S188 | Syn |

| 71377 | TAT indel | Inter | NA | X |

| 74293 | A/C | ORF40 | G918 | Syn |

| 75103 | A/G | ORF40 | L1188 | Syn |

| 77154 | T/C | ORF42 | Q647 | Syn |

| 78385 | C/T | ORF43 | F72 | Syn |

| 78545 | G/A | ORF43 | V126 | V126I |

| 80306 | G/T | inter | NA | X |

| 81854 | G/A | ORF42 | T247 | T247M |

| 105923 | G/T | ORF62 | R1071 | Syn |

| 110169 | G/A | Inter | NA | X |

| 110243 | T/A | Inter | NA | X |

| 110393 | C insert | Inter | NA | X |

| 117413 | C/A | ORF68 | L535I | L535I |

The polymorphisms that distinguish clade 3 from clade 1 in an updated phylogenetic tree (2, 26, 34) are shown. Differences relative to the reference sequence (Dumas, clade 1) are denoted by an amino acid change if nonsynonymous or with “Syn” if synonymous; a simple X denotes a change within a noncoding region of the sequence. NA, not available. Inter, intergenic.

When the five reiteration regions (R1 to R5) were examined, based on the subunit nomenclature outlined in Tyler et al. (34), R1 exhibited the subunit pattern ABD1AD2BABBABBAB, R2 was BEEABBx, R3 was CACACA, R4 was AAAAAAx, and R5 was ABA2. No new subunit types were found in Ellen, and the number of subunits identified in each reiteration region was similar to what has been reported in previously sequenced VZV isolates. Both R2 and R3 were found to be variable within VZV Ellen, and the reported subunit patterns represented the consensus from multiple clones. The origin of replication in VZV Ellen was found to match the genotype-specific SNP pattern outlined previously (26), with no major divergences from other clade 3 isolates in the TA and GA subunit distributions. Originally considered a potential contributing factor to attenuation in VZV, the origins of replication in VZV Ellen and Oka vaccine derivatives show no commonalities in SNP patterns, nor do they contain marked differences in the number of TA/GA subunits from other wild-type isolates.

Comparison of SNPs in VZV Ellen IE62 with VZV vaccine Oka and high-passage-number laboratory strains.

Based on prior vOka research, SNPs within the gene encoding the major regulatory IE62 protein have been considered possible determinants of VZV attenuation because of their frequency and the role of IE62 in the transcription of all VZV genes. VZV vaccine was produced in Japan by serial passaging in cultured cells. From the same seed lot, there are currently three vaccine preparations being produced by different pharmaceutical companies, and all of the vaccines have been completely sequenced. The three vaccine preparations are called vOka (Biken, Japan), Varivax (Merck), and Varilrix (Glaxo, United Kingdom). The attenuated Ellen strain has been passaged at least 90 times. Therefore, some polymorphisms arising from serial passaging can be identified by comparison with complete sequences of the laboratory strain VZV 32 after 5, 22, and 72 passages.

VZV Ellen shared two nonsynonymous ORF62 polymorphisms with the three vaccine Oka strains (Table 2). The first ORF62 mutation involved nucleotide (nt) 107252 and converted a serine to a glycine. This mutation fell within region II of the IE62 amino acid sequence (28). Region II is the most highly conserved region within the IE62 regulatory protein and its homologs in other herpesviruses. Within region II itself, the S628G mutation fell within the DNA binding domain (residues 468 to 640), which overlaps with the dimerization domain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Prior experiments have shown that a subdomain between residues 588 and 647 is required for dimerization. The second IE62 mutation involved nucleotide 106262, which converted an arginine to a glycine. This R958G mutation fell within region IV (residues 735 to 1147). The functions of region IV have not been as well defined as those of other regions (see Fig. S1). Of great interest, both of these ORF62 SNPs were found in passage 72 (P72) of the VZV 32 strain (VZV 32-P72) but were absent from earlier passages. In short, the presence of these two ORF62 SNPs in the attenuated Ellen strain likely resulted from serial passaging.

Table 2.

Polymorphic changes to the VZV Ellen genome compared to genomes of the VZV vaccine strains and VZV 32 at passage 72a

| Reference sequence nt | ORF | Nucleotide change | Amino acid | Ellen | VZV 32-P72 | pOKA | vOKA | Varilrix | Varivax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 386 | ORF0 | T/C | Y72 | Y72H | |||||

| 560 | ORF0 | T/C | *130 | *130R | *130R | *130R | *130R | ||

| 5421 | ORF6 | C/T | A1053 | A1053T | |||||

| 10536 | ORF8 | A/G | D44 | Syn | |||||

| 13977 | ORF11 | G/A | A130 | A130T | |||||

| 27634 | ORF19 | T/C | L404 | Syn | |||||

| 31331 | ORF21 | C/T | I191 | Syn | |||||

| 46909 | ORF27 | G/A | Q261 | Syn | |||||

| 60990 | ORF33 | C/A | P383 | Syn | |||||

| 61267 | ORF33 | T/C | H291 | H291R | |||||

| 64884 | ORF36 | A/G | T26 | Syn | |||||

| 85181 | ORF48 | C/T | T172 | T172I | |||||

| 95355 | ORF54 | T/C | V210 | Syn | |||||

| 96166 | ORF55 | T/C | R57 | Syn | |||||

| 98816 | ORF56 | A/G | A83 | Syn | |||||

| 99431 | ORF57 | A/G | C66 | C66R | |||||

| 100450 | ORF59 | T/C | Q257 | Q257R | |||||

| 100749 | ORF59 | A/G | H157 | Syn | |||||

| 104470 | ORF61 | C/T | A6 | A6T | |||||

| 105356 | ORF62 | T/C | I1260 | I1260V | I1260V | I1260V | I1260V | ||

| 105374 | ORF62 | A/C | S1254 | S1254A | |||||

| 105406 | ORF62 | T/C | E1243 | E1243G | |||||

| 105413 | ORF62 | T/C | S1241 | S1241G | |||||

| 105490 | ORF62 | T/C | Q1215 | Q1215R | |||||

| 105855 | ORF62 | T/C | A1093 | Syn | |||||

| 105919 | ORF62 | T/Y | Q1072 | Q1072Q/R | |||||

| 105964 | ORF62 | T/Y | Q1057 | Q1057Q/R | |||||

| 106001 | ORF62 | T/C | K1045 | K1045E | |||||

| 106052 | ORF62 | A/G | L1028 | Syn | |||||

| 106247 | ORF62 | A/G | L963 | Syn | |||||

| 106262 | ORF62 | T/C | R958 | R958G | R958G | R958G | R958G | R958G | |

| 106831 | ORF62 | T/C | Q768 | Q768R | Q768Q/R | ||||

| 107252 | ORF62 | T/C | S628 | S628G | S628G | S628G | S628G | S628G | |

| 108551 | ORF62 | T/C | N195 | N195D | |||||

| 108564 | ORF62 | T/C | Q190 | Syn | |||||

| 108618 | ORF62 | A/G | V172 | Syn |

SNPs compared with the reference sequence (Dumas) are denoted by an amino acid if nonsynonymous or with “Syn” if synonymous. An asterisk indicates a stop codon. Shading of a row indicates a possible shared attenuation determinant. A blank cell indicates the absence of any mutation at the site. Note that the ORF33, ORF59, and ORF62 genes are transcribed from the negative strand; therefore, the designation of the amino acid number declines with an increasing nucleotide number.

Comparison of SNPs in VZV Ellen ORF0 to VZV vaccine Oka.

Of particular interest with regard to the search for determinants of attenuation, VZV Ellen shared the same ORF0 stop codon mutation with all three vaccine stock viruses (Table 2). This mutation in Ellen ORF0 was present in 100% of 37 pyrosequencing reads. ORF0 (also called ORF S/liter) was first discovered by Kemble et al. (17) during their analysis of the pOka and vOka sequences. Further, they observed that a nucleotide transition (TGA to CGA) in vOka eliminates a stop codon after residue 129 in the wild-type ORF0. The mutation is designated *130R in Table 2. Thus, the mutated ORF0 protein is extended by 92 amino acids in vOka, until a second stop codon at position 221 is reached within ORF1 (Fig. 1). There is a potential splice region, beginning at nt 583, which if removed converts the final ORF0 product into a protein with 155 residues. Furthermore, each of the C termini of the two proteins lacking the stop codon (nonspliced and spliced) encodes a different amino acid sequence (Fig. 1). Of importance, the VZV Ellen ORF0 sequence contained the same point mutation in the stop codon; specifically, at Ellen nt 561 (same location as Dumas nt 560 and vOka nt 559), thymidine was replaced by cytosine (TGA to CGA), with the subsequent addition of an arginine residue to the elongated ORF0 protein. VZV Ellen also retained the potential splice region found in the vOka sequence between nt 583 and nt 714. Note that enumeration for the initial nucleotide of the start codon of ORF0 is 172 for vOka, 173 for Dumas, and 174 for Ellen because of homopolymer differences at the far 5′ end of the respective sequences.

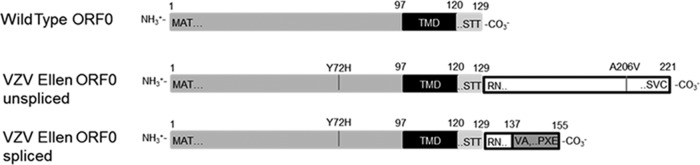

Fig 1.

Representations of the amino acid sequences of VZV wild-type ORF0 and the two mutated forms of VZV Ellen ORF0, unspliced and spliced. In each model, the unmutated N termini are light gray, transmembrane domains (TMD) are black, and new sequences are white or dark gray. Numbers on top of each representation are amino acid positions. Within the representation are the initial and final amino acids in segments of the sequences. VZV Ellen has an extended C terminus (white) due to a mutation in the stop codon. The C terminus of the putative spliced form is composed of a small portion of the elongated Ellen C terminus (white) plus a completely new sequence due to a frameshift at the splice site (dark gray). VZV Ellen ORF0 has a point mutation at residue 72 that is not found in wild-type sequences and a point mutation at residue 206 that differs from vOKA, the other strain that shares the elongated C terminus.

Two putative N-linked glycosylation sites (N-X-S/T) have also been defined in the vOka ORF0 protein sequence, beginning with asparagine at residues 65 and 126 (20). The sites are present in both the wild-type and vaccine virus sequences. Of note, the same asparagine at residue 126 was present in the Ellen sequence with an important caveat. In 37% of the pyrosequencing reads (14/38), there was a coding mutation within the N-linked glycosylation motif that converted the middle X amino acid to proline (N-P-T), thereby blocking attachment of a sugar moiety at the asparagine residue. Finally, Ellen had a distinctive coding SNP at residue 71 (Y72H), which was not present in vOka or any wild-type virus examined thus far (Fig. 1).

Comparison of other SNPS in the different VZV strains.

We first postulated that high numbers of passages may lead invariably to mutations in ORF0, but that was proven untrue by inspection of the sequence of passage 72 of VZV 32, which lacks a mutation in the ORF0 stop codon (Tables 1 and 2) (34). On the other hand, VZV 32-P72 IE62 has a mutation at base 105356 (as does vOka), but this mutation was not found in VZV Ellen. However, an I1260V mutation is unlikely to lead to any biological compromise.

In addition to the SNPs in ORF0 and ORF62, vOka differs from pOka by having coding SNPs in the following ORFs: 6, 9, 10, 21, 31, 39, 50, 52, 55, 59, and 64 (12). When VZV Ellen sequence was compared with that of vOka, the Ellen sequence lacked any of the other SNPs mentioned above that differentiate pOka from vOka. As noted in Table 2, the Ellen sequence did contain other SNPs different from the Dumas sequence that were not clade specific. These SNPs may have arisen during a high number of passages of the Ellen strain. In any case, these Ellen SNPs were not present in any of the three vaccine strains and therefore were considered unlikely determinants of attenuation. Again, we emphasize that the vOka vaccine strain represents a mixture of quasispecies (12). For that reason, we sequenced ORF0 in our vOka cosmid used in the published SCID-hu experiments (21); we discovered that it lacked the ORF0 stop codon mutation (data not shown).

Finally, we note that the Japanese Oka viruses are members of clade 2, which represents an Asian strain (14). To provide further assurance that the parental Oka strain accurately reflects a wild-type phenotype, we completely sequenced a second wild-type clade 2 virus called LAX1, which was passaged less than 10 times. As seen with pOka, the LAX1 sequence lacked the Ellen-specific SNPs in ORF0 and ORF62 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Additional differences between pOka, vOka, and LAX1 are also enumerated in Table S1.

Imaging of mutated ORF0 protein in VZV Ellen-infected cells.

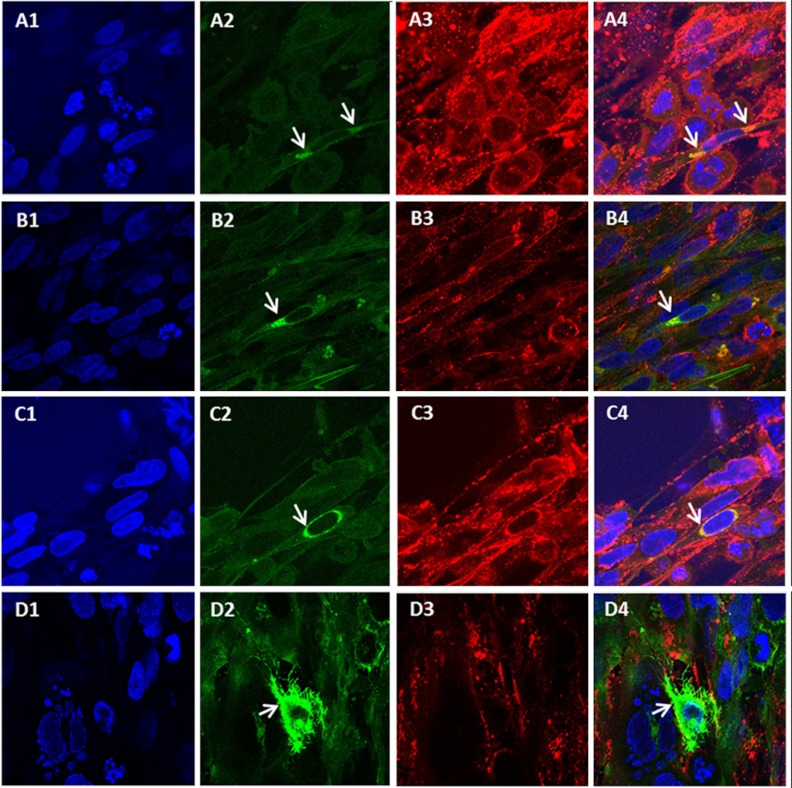

Based on the above bioinformatics analyses, we concluded that mutated ORF0 was an important determinant of VZV attenuation. The wild-type ORF0 product has been classified as a tail-anchored type 2 transmembrane protein, based on studies of its HSV2 homolog, called UL56 (19). Because the localization and trafficking of the ORF0 protein with a stop codon mutation had not been extensively investigated in prior reports, we visualized this protein within infected cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Fig. 2). When we examined the monolayers at the different time points after infection, we noticed that relatively few cells expressed ORF0 at 24 and 48 hpi (data not shown). Even at 72 hpi, far fewer cells expressed ORF0 than the predominant VZV gE glycoprotein (13). When infected monolayers were observed by confocal microscopy at higher magnification (×630), the distribution of ORF0 varied from positive cell to positive cell. In many ORF0-positive cells, ORF0 reactivity was restricted to a perinuclear triangular pattern, indicative of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localization (Fig. 2A and B). In an occasional cell, ORF0 reactivity was observed circumferentially around the entire nucleus (Fig. 2C). Finally, in a smaller number of ORF0 reactive cells, ORF0 was obviously distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2D).

Fig 2.

Imaging of mutated ORF0 and gE proteins in VZV Ellen-infected cells. MRC-5 cells were infected with VZV Ellen and imaged at ×630 by laser scanning confocal microscopy at 72 hpi. The monolayers were immunolabeled with antibodies to VZV gE (red) and ORF0 protein (green); nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 DNA dye (blue). The fourth panel in each set of four panels is a merged image. Arrows indicate ORF0 protein. (A1 to A4) ORF0 protein at the ER of VZV Ellen-infected fibroblast cells. (B1 to B4) Another example of ER localization of the ORF0 protein. (C1 to C4) An unusual distribution of ORF0 protein around the outer nuclear membrane of an infected cell. (D1 to D4) ORF0 protein in the cytoplasm of an infected cell.

Visualization of ORF0 protein within VZV-infected cells in 3D.

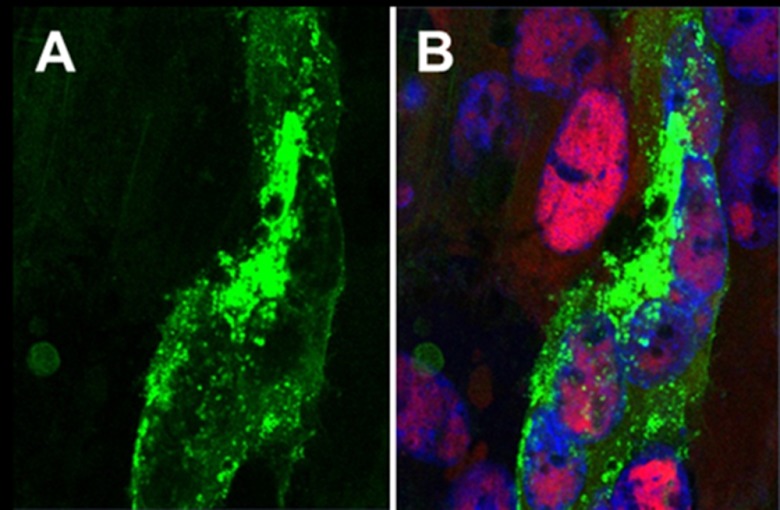

Because the patterns of ORF0 localization within VZV Ellen-infected cells shown in Fig. 2 were somewhat different from localization patterns of other VZV proteins studied by this laboratory, we turned to an imaging software program, Imaris, in order to provide a more informative 3D reconstruction of the image sets obtained by confocal microscopy (27). We also included image sets of VZV 32-infected cells expressing wild-type ORF0 in this comparative analysis. Through the Imaris program, we were able to stack multiple serial images vertically and then examine the localization of ORF0 protein in 3D as we rotated the image stacks (Fig. 3; see also the 3D images in Movie S1 in the supplemental material). Through this technology, we extended the observations in Fig. 2 by confirming that the ORF0 protein occasionally had a perinuclear distribution, often within perinuclear vesicles (data not shown). Subsequent images verified that the ORF0 protein eventually was found throughout the cytoplasm but only in a very small percentage of the infected cell population. The ORF0 protein was also detected in the cytoplasm surrounding small syncytia, another indication that the ORF0 protein was a marker for the late phase of viral replication (Fig. 3). In fibroblast cells, only small syncytia ever develop after VZV infection, and these polykaryons are found only during the last phase of the infectious cycle. When the relative numbers of ORF0-positive cells were compared between VZV Ellen- and VZV 32-infected monolayers, we estimated that VZV Ellen monolayers exhibited a greater number of positive cells (see the 3D images in Movies S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Again, we note that the overall number of VZV ORF0-positive cells was limited in both monolayers and included only a small fraction of the infected cell population.

Fig 3.

Visualization of ORF0 protein by 3D imaging in both VZV Ellen- and VZV 32-infected cells. As an extension of the confocal microscopy shown in Fig. 2, additional monolayers were infected with VZV Ellen or VZV 32 and subsequently immunolabeled with antibodies to ORF0 protein and IE62 protein. Then a Z-stack of serial images, each 0.2 μm in depth, was collected by laser scanning confocal microscopy; in turn, the multiple individual images were reconstructed with the aid of the Imaris visualization software program (27) in order to create a 3D representation of the infected cell or syncytium. (A) Small syncytium in VZV Ellen-infected monolayer immunolabeled for ORF0 protein (green). (B) Merged image of the same syncytium immunolabeled for IE62 protein (red), in addition to the ORF0 protein (green) and the blue Hoechst DNA dye. Note the presence of three nuclei containing IE62 within the small syncytium. For a 3D reconstruction of the syncytium within VZV Ellen-infected cells, see Movie S1 in the supplemental material; for a 3D reconstruction of a similarly immunolabeled VZV 32-infected monolayer see Movie S2.

Analyses of ORF0 transcription and kinetics of protein expression.

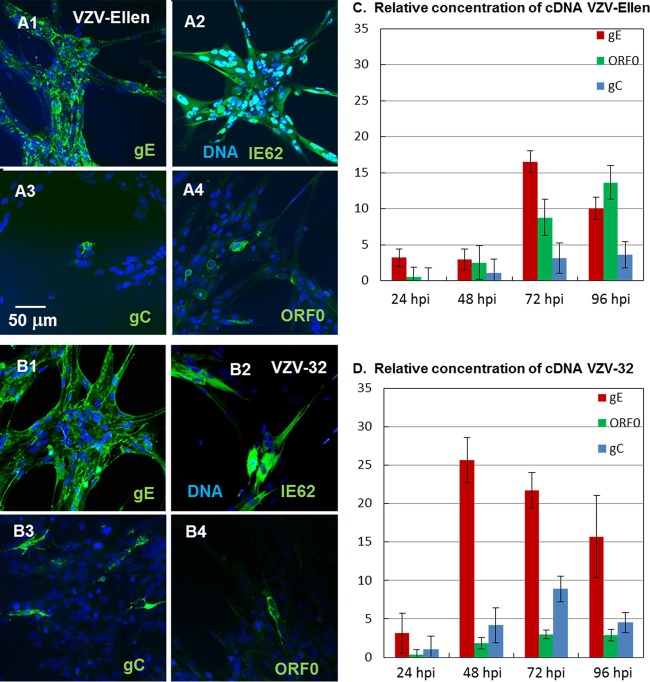

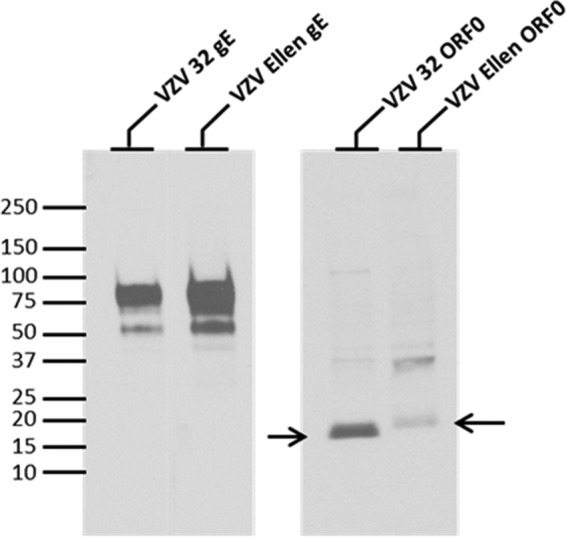

As noted above, the delayed and reduced ORF0 expression, compared with gE, resembled the well-documented and similarly reduced gC expression in VZV-infected cells until late in the infectious cycle. Therefore, we compared the expression of ORF0 protein with that of VZV gC in both VZV Ellen-infected cells (Fig. 4A) and VZV 32-infected cells (Fig. 4B), with similar findings, namely, relatively few positive cells within a monolayer with advanced infection. To confirm the low expression level of ORF0 in VZV-infected cells observed in the confocal micrographs, we extracted RNA and measured the relative amounts of ORF0, gC (ORF14), and gE (ORF68) transcription in infected fibroblast cells at increasing times postinfection by qRT-PCR. While VZV gE mRNA levels rapidly increased in both VZV Ellen- and VZV 32-infected monolayers, as expected from prior studies, VZV ORF0 mRNA levels monotonically increased but were always markedly less than those of gE, even at 72 hpi (Fig. 4C and D). Only at 96 hpi was noticeable ORF0 mRNA detectable in VZV Ellen, a result suggested in the 3D images shown in Fig. 3. Also, as suggested by the confocal images in Fig. 4A and B, relatively low levels of VZV gC mRNA were found in both monolayers at all time points. Finally, to document the slightly higher predicted molecular weight (MW) of mutated ORF0 protein lacking its original stop codon, compared with wild-type ORF0 protein, we compared the migration of the respective [35S]methionine-cysteine-labeled products by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Analyses of ORF0 in VZV Ellen- and VZV 32-infected cells by quantitative RT-PCR. Fibroblast cells were infected with VZV Ellen or VZV 32 and subsequently imaged by laser scanning confocal microscopy at 72 hpi. (A1 to A4) Monolayers of VZV Ellen-infected cells were observed with a 200× lens after cells were labeled with the Hoechst 33342 DNA stain and antibodies to VZV gE (A1), IE62 (A2), gC (A3), or ORF0 (A4). (B1 to B4) Monolayers of VZV 32-infected cells were processed similarly to VZV Ellen-infected cells. (C) As a corollary to the VZV Ellen protein expression assays shown in panel A, measurements were obtained of VZV Ellen gE (ORF68), gC(ORF14), and ORF0 mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR at increasing times postinfection. (D) As a corollary to the VZV 32 protein expression assays shown in panel B, similar mRNA levels were obtained in VZV 32-infected cells.

Fig 5.

Precipitation of radiolabeled wild-type and mutated ORF0 proteins. Radiolabeled VZV 32- or VZV Ellen-infected cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the protein indicated above each lane, as described in Materials and Methods. The VZV proteins were separated on a 4 to 20% SDS-acrylamide gel. Arrows indicate the positions of VZV 32 ORF0 and VZV Ellen ORF0. Immunoprecipitation of the VZV gE glycoprotein was included as a positive control. Under the radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation conditions of this experiment, the relative amounts of radiolabeled proteins between the two strains were not intended to indicate quantitation. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are included in left margin.

The above imaging results suggested that the mutated ORF0 protein, like its HSV-2 UL56 homolog, first entered the ER/Golgi compartment before transiting through the cytoplasm (19). When we compared all our data about ORF0 with three previously examined VZV proteins—IE62, gE, and gC—the ORF0 results most closely resembled those of VZV gC (31, 32). In the VZV system, the gC product is expressed late in the infectious cycle in cultured cells, at least 24 h after abundant IE62 and gE expression. Taken together, the above results suggested that VZV ORF0 should be assigned to the late kinetic phase of VZV replication.

DISCUSSION

Since the publication of the complete sequences of pOka and vOka in 2002, there have been many attempts to define SNPs that might be associated with attenuation of the live attenuated varicella vaccine. Currently, the concept has arisen that VZV attenuation requires a set of as yet undetermined SNPs within two or more ORFs, one of which is likely the IE62 gene. The importance of VZV Ellen is that this strain, like vOka, has been shown to be attenuated when tested in human skin xenografts in the SCID mouse model of VZV pathogenesis (21). At the time, this result was surprising because no formal attempt had even been made to attenuate the Ellen strain. Yet without the whole Ellen genome sequence, further analysis was impossible. Thus, completion of the Ellen sequencing provided critical data for a comparative bioinformatics analysis with vOka. The fact that Ellen and Oka strains belong to different clades made this search for attenuation determinants somewhat easier. Although both the Ellen and vOka genomes harbor coding SNPs in several ORFs, there is very little overlap.

Identification of the same stop codon SNP (*130R) in Ellen ORF0 and vOka ORF0, in the absence of other common SNPS between Ellen and vOka, was certainly not predictable. Therefore, an important question is whether VZV vOka and VZV Ellen could have mutated at the same nucleotide with the same substitution by random chance. The probability that any one nucleotide will mutate due to an error during genome replication is proportional to the average genomic mutation rate, is estimated to be 0.0034 mutations per genome per replication cycle for DNA viruses (7). For VZV with approximately 125,000 bases, the genomic mutation rate is 2.7 × 10−8. Of course, both vOka and Ellen have undergone numerous passages, including two to three replication cycles per passage, prior to sequencing. Therefore, we estimate the probability that nt 560 would mutate in the range of 1 × 10−4. The probability of an identical transitional base change in a second strain not connected by a clade relationship to the first strain is 1 in 1 × 10−8; otherwise stated, there is a 1 × 10−8 probability that nt 560 would undergo the same transition between two independent strains by chance. In short, we hypothesize that the nt 560 T/C mutation in the ORF0 stop codon did not occur by chance; instead, the SNP likely increases viral adaptability for growth in cell culture and, at the same time, leads to an attenuation phenotype.

The Oka vaccine product is known to consist of a mixture of viral genomes, resulting in what is sometimes called quasispecies. By some bioinformatics analyses, there are 21 nonsynonymous SNPs within 13 vOka ORFs among the quasispecies, compared with pOka (12, 34). Because the ORF with the largest SNP number encodes IE62, attention focused initially on this regulatory protein as possibly being a primary determinant of attenuation. Since IE62, the homolog of HSV ICP4, is the major VZV transactivator, that hypothesis appeared reasonable (22, 25). Yet studies of IE62 promoter activity with constructs containing various mutations within IE62 have shown only modest deficits in function evaluated in vitro (5). Further, recombinant chimeric viruses made from cosmids consisting of parental and vaccine Oka segments have not defined specific ORF62 SNPs associated with altered replication in vitro (29, 38). These experiments showed that chimeric viruses with various segments from vOka were attenuated, independently of ORF62. However, these studies of the pOka/vOka chimeric viruses did not address the role of the ORF0 mutation in attenuation because ORF0 in the vOka cosmid has the wild-type gene sequence. In other words, by chance during construction of the vOka cosmid, we selected a vOka quasispecies that lacked the ORF0 stop codon mutation. These data demonstrate again that the vaccine consists of a mixture of genomes.

Since the deficit in virulence of both the vOka and Ellen strains (with mutated ORF0 genes) has been shown in comparison to pOka in human skin xenografts in vivo, as well as other strains with an intact ORF0 gene, this work provides the first evidence for identification of one of the attenuation SNPs in the live attenuated varicella vaccine genome. The above claim is bolstered by the recent publication of a third unrelated VZV sequence. In a completely independent pharmaceutical endeavor, a second live attenuated varicella vaccine called Suduvax has been produced and distributed to children in South Korea since 1994 (18). As with vOka, the South Korean vaccine product was created after serial passaging of a wild-type Korean VZV strain in cultured cells. The attenuation methodology was extremely similar to that for vOka, namely, 10 passages in human fibroblast cells, 12 in guinea pig cells, and then a few more passages in human cells. Of importance, this South Korean vaccine has been sequenced and shown to possess the same ORF0 stop codon mutation as vOka and Ellen (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, there are now three known attenuated VZV strains that contain the same ORF0 polymorphism: vOka, Ellen, and Suduvax. The same SNP is not found in any other completely sequenced VZV genome (34, 37). Based on the previously described statistical calculations, the probability that three geographically unrelated attenuated strains from Japan, South Korea, and the United States would harbor the same transition within the same ORF0 by chance is 1 × 10−12, obviously highly unlikely. In short, the ORF0 SNP is a likely determinant of attenuation. Even though a role for mutated ORF0 is now recognized, an abundance of prior research on varicella vaccine from several laboratories cited here suggests that additional determinants of attenuation remain to be discovered within other ORFs of the genome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Graham Tipples for his continuing support of this project during his tenure at the National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

This VZV research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Y.M.), as well as grants AI53846 (A.M.A.) and AI89716 (C.G.) from the NIH, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 July 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arvin AM. 2006. Investigations of the pathogenesis of varicella zoster virus infection in the SCIDhu mouse model. Herpes 13:75–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breuer J, Grose C, Norberg P, Tipples G, Schmid DS. 2010. A proposal for a common nomenclature for viral clades that form the species varicella-zoster virus: summary of VZV Nomenclature Meeting 2008, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, 24–25 July 2008. J. Gen. Virol. 91:821–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brunell PA, Casey HL. 1964. Crude tissue culture antigen for determination of varicella-zoster complement fixing antibody. Public Health Rep. 79:839–842 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carpenter JE, Hutchinson JA, Jackson W, Grose C. 2008. Egress of light particles among filopodia on the surface of varicella-zoster virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 82:2821–2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH, Gomi Y, Yamanishi K, Cohen JI. 2006. Comparison of virus transcription during lytic infection of the Oka parental and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus. J. Virol. 80:2076–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davison AJ, Scott JE. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1759–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drake JW. 1999. The distribution of rates of spontaneous mutation over viruses, prokaryotes, and eukaryotes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 870:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Droege M, Hill B. 2008. The Genome Sequencer FLX System—longer reads, more applications, straight forward bioinformatics and more complete data sets. J. Biotechnol. 136:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duus KM, Hatfield C, Grose C. 1995. Cell surface expression and fusion by the varicella-zoster virus gH:gL glycoprotein complex: analysis by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Virology 210:429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faga B, Maury W, Bruckner DA, Grose C. 2001. Identification and mapping of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the varicella-zoster virus genome. Virology 280:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gershon AA, Arvin AM, Levin MJ, Seward JF, Schmid DS. 2008. Varicella vaccine in the United States: a decade of prevention and the way forward. J. Infect. Dis. 197(Suppl. 2):S39–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gomi Y, et al. 2002. Comparison of the complete DNA sequences of the Oka varicella vaccine and its parental virus. J. Virol. 76:11447–11459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grose C. 1990. Glycoproteins encoded by varicella-zoster virus: biosynthesis, phosphorylation, and intracellular trafficking. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44:59–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grose C. 3 July 2012. Pangaea and the out-of-Africa model of varicella-zoster virus evolution and phylogeography. J. Virol. doi:10.1128/JVI.00357-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grose C, et al. 2004. Complete DNA sequence analyses of the first two varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E (D150N) mutant viruses found in North America: evolution of genotypes with an accelerated cell spread phenotype. J. Virol. 78:6799–6807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaufer BB, Smejkal B, Osterrieder N. 2010. The varicella-zoster virus ORFS/L (ORF0) gene is required for efficient viral replication and contains an element involved in DNA cleavage. J. Virol. 84:11661–11669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kemble GW, et al. 2000. Open reading frame S/L of varicella-zoster virus encodes a cytoplasmic protein expressed in infected cells. J. Virol. 74:11311–11321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JI, et al. 2011. Sequencing and characterization of Varicella-zoster virus vaccine strain SuduVax. Virol. J. 8:547 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koshizuka T, et al. 2002. Identification and characterization of the UL56 gene product of herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 76:6718–6728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koshizuka T, Ota M, Yamanishi K, Mori Y. 2010. Characterization of varicella-zoster virus-encoded ORF0 gene—comparison of parental and vaccine strains. Virology 405:280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moffat JF, et al. 1998. Attenuation of the vaccine Oka strain of varicella-zoster virus and role of glycoprotein C in alphaherpesvirus virulence demonstrated in the SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 72:965–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Smith HA, Cohen JI. 1994. Varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 4 protein is functionally distinct from and does not complement its herpes simplex virus type 1 homolog, ICP27. J. Virol. 68:1987–1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ng TI, Keenan L, Kinchington PR, Grose C. 1994. Phosphorylation of varicella-zoster virus open reading frame (ORF) 62 regulatory product by viral ORF 47-associated protein kinase. J. Virol. 68:1350–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oxman MN, et al. 2005. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:2271–2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perera LP, et al. 1993. A major transactivator of varicella-zoster virus, the immediate-early protein IE62, contains a potent N-terminal activation domain. J. Virol. 67:4474–4483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peters GA, et al. 2006. A full-genome phylogenetic analysis of varicella-zoster virus reveals a novel origin of replication-based genotyping scheme and evidence of recombination between major circulating clades. J. Virol. 80:9850–9860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rueden CT, Eliceiri KW. 2007. Visualization approaches for multidimensional biological image data. Biotechniques 43(1 Suppl):31, 33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruyechan WT. 2010. Roles of cellular transcription factors in VZV replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 342:43–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sato B, et al. 2003. Mutational analysis of open reading frames 62 and 71, encoding the varicella-zoster virus immediate-early transactivating protein, IE62, and effects on replication in vitro and in skin xenografts in the SCID-hu mouse in vivo. J. Virol. 77:5607–5620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schuster SC. 2008. Next-generation sequencing transforms today's biology. Nat. Methods 5:16–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Storlie J, Carpenter JE, Jackson W, Grose C. 2008. Discordant varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein C expression and localization between cultured cells and human skin vesicles. Virology 382:171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Storlie J, Jackson W, Hutchinson J, Grose C. 2006. Delayed biosynthesis of varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein C: upregulation by hexamethylene bisacetamide and retinoic acid treatment of infected cells. J. Virol. 80:9544–9556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takahashi M. 2004. Effectiveness of live varicella vaccine. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4:199–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tyler SD, et al. 2007. Genomic cartography of varicella-zoster virus: a complete genome-based analysis of strain variability with implications for attenuation and phenotypic differences. Virology 359:447–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weller TH. 1983. Varicella and herpes zoster. Changing concepts of the natural history, control, and importance of a not-so-benign virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 309:1434–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamagishi Y, et al. 2008. Varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein M homolog is glycosylated, is expressed on the viral envelope, and functions in virus cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 82:795–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zell R, et al. 2012. Sequencing of 21 varicella-zoster virus genomes reveals two novel genotypes and evidence of recombination. J. Virol. 86:1608–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zerboni L, et al. 2005. Analysis of varicella zoster virus attenuation by evaluation of chimeric parent Oka/vaccine Oka recombinant viruses in skin xenografts in the SCIDhu mouse model. Virology 332:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.