Abstract

We investigated the ability of compounds interfering with iron metabolism to inhibit the growth of Acinetobacter baumannii. Iron restriction with transferrin or 2,2-bipyridyl significantly inhibited A. baumannii growth in vitro. Gallium nitrate alone was moderately effective at reducing A. baumannii growth but became bacteriostatic in the presence of serum or transferrin. More importantly, gallium nitrate treatment reduced lung bacterial burdens in mice. The use of gallium-based therapies shows promise for the control of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii.

TEXT

Acinetobacter baumannii has emerged as a major cause of both community-associated and nosocomial infections worldwide. Infections have become increasingly difficult to treat because of the rapid development of A. baumannii antibiotic resistance. Counteracting the action of virulence factors represents a novel strategy of infection control with potentially high specificity and low impact on the host. Hence, identification of the critical factors necessary for the in vivo success of the pathogen might reveal novel therapeutic targets.

One characteristic shared by virulent bacteria is their ability to acquire iron in the blood and tissues, where its availability is low. Conversely, several host factors exist whose role is to restrict iron and form a nutritional barrier (reviewed in reference 9). Pathogen iron acquisition could be further disrupted by using biologically compatible chelators (6–8) or by introducing gallium as a competitor (1).

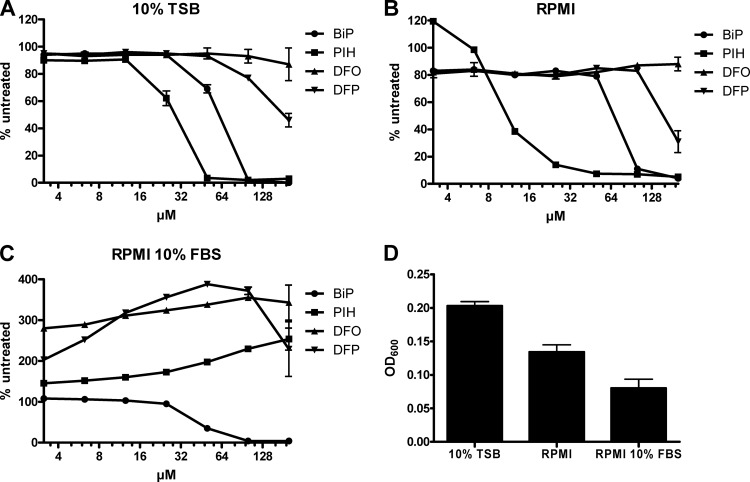

To examine the biological activity of iron-restricting compounds against A. baumannii, we first investigated the effect of a selection of iron chelators on A. baumannii ATCC 17978 growth in different media. 2,2-Bipyridyl (BiP) is a classical iron chelator and was chosen as a positive control for both metal depletion and growth inhibition of many organisms. Pyridoxal isonicotinyl hydrazone (PIH) is a potent cell-permeable chelator, deferoxamine (DFO) is a bacteria-derived siderophore, and deferiprone (DFP) is a synthetic bidentate iron chelator. All three are specific for Fe(III), show low toxicity, and can be used in iron overload therapy. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) over a 5-h incubation period at 37°C in media containing various concentrations of the inhibitors. In iron-rich 10% Trypticase soy broth and in RPMI 1640, which contains only trace levels of iron, BiP and PIH were able to suppress growth of A. baumannii (Fig. 1A and B). DFO was inactive in both media and DFP could only partially suppress growth, which suggests that they are unable to efficiently sequester iron from the bacteria. Interestingly, in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), PIH, DFO, and DFP promoted the growth of A. baumannii while BiP was again suppressive (Fig. 1C). The situation in serum would indicate that such compounds can mobilize iron from transferrin or other stores and/or shuttle it to the pathogen, a contraindication for antimicrobial therapy. Iron mobilization from transferrin has been demonstrated in DFP (11), and the use of DFO has been associated with the exacerbation of mucormycosis in animal and humans (3). BiP is a cell-permeable Fe(II)-specific chelator that acts by directly depleting intracellular stores of ferrous iron and thus can retain its activity in the presence of serum. However, the neurotoxicity of BiP precludes its therapeutic use (12).

Fig 1.

Effect of iron chelators on A. baumannii growth in vitro. A. baumannii ATCC 17978 was cultured in 10% TSB/90% saline (A), RPMI medium (B), or RPMI plus 10% FBS (C), in the presence of the indicated concentrations of iron chelators. BiP, 2,2-bipyridyl. PIH, pyridoxal isonicotinyl hydrazone. DFO, deferoxamine. DFP, deferiprone. The OD600 was taken after 5 h and expressed as a percentage of results for untreated samples ± standard deviation. (D) OD600 of untreated samples for each medium. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

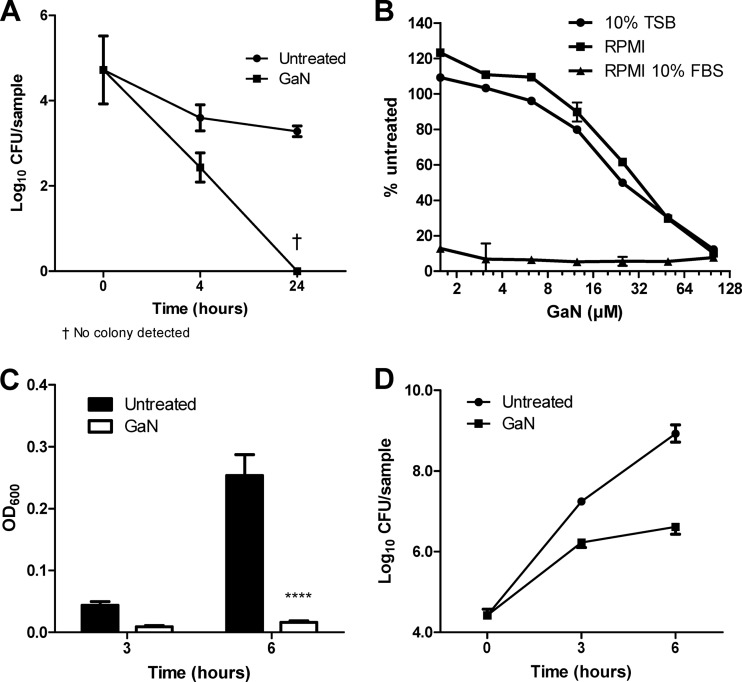

A different iron restriction strategy that has been shown to be both nontoxic and antimicrobial is the use of gallium (1), a transition metal with an atomic radius and valence that make it resemble ferric iron, Fe(III), but unable to undergo oxidation reduction. We examined the effect of gallium nitrate (GaN) on the growth of A. baumannii and found that its effect was also highly dependent on the medium. In 0.85% saline, a condition that does not support growth, A. baumannii viability initially decreased but later stabilized. In the presence of 50 μM gallium, bacterial viability was significantly reduced, with no viable bacteria recovered at 24 h (P < 0.0001, two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (Fig. 2A). Although GaN was bactericidal under conditions that did not support growth, it performed poorly in iron-rich, 10% Trypticase soy broth (TSB), with a 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90) of >100 μM, and only slightly better in iron-poor RPMI, with an IC90 of 100 μM. However, in the presence of serum, the effect of gallium was drastically enhanced, with an IC90 of 3.1 μM (Fig. 2B). Over time, 10 μM GaN in 10% FBS was able to suppress growth of A. baumannii, with gallium-treated cultures containing >200 times fewer viable bacteria than control cultures (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig 2.

Inhibition of A. baumannii growth by gallium nitrate in different culture media. (A) A. baumannii ATCC 17978 stocks were inoculated at time zero at 6.2 × 104 CFU per sample in 0.85% NaCl in the presence or absence of 50 μM GaN. Samples were incubated at 37°C with shaking, and the number of viable colonies was determined at 4 and 24 h. (B) A. baumannii was cultured in various media in the presence of the indicated concentrations of GaN. After 5 h, the absorbance at 600 nm was measured and the results were expressed as a percentage of results for untreated (0 μM GaN) samples ± standard deviation of triplicate wells. (C) A. baumannii was grown in RPMI plus 10% FBS in the presence of 0 or 10 μM GaN, and the OD600 was measured at 3 and 6 h ± standard deviation of triplicate wells. ****, P < 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA. (D) Viable counts from the samples in panel C were determined at each time point along with the initial inoculum (at time zero). Results in panels A and D are expressed as log10 CFU per triplicate sample ± standard deviation. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

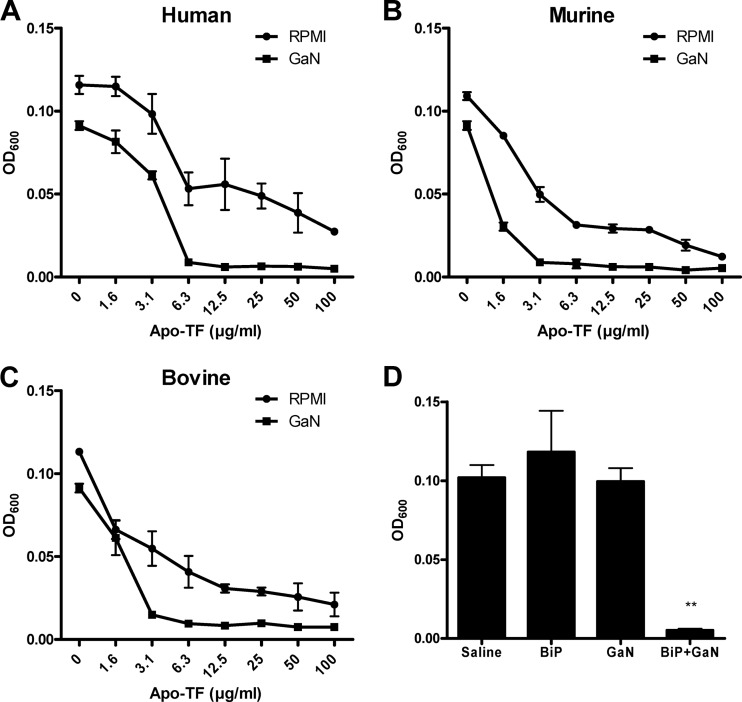

Since transferrin is the main extracellular iron-binding molecule in the bloodstream, we hypothesized that it was responsible for the synergistic effect of gallium and serum. In fact, human, murine, or bovine apo-transferrin alone slows, but does not completely suppress, the overnight growth of A. baumannii in RPMI. In the presence of 10 μM GaN, overnight growth was largely unaffected in RPMI but was nearly stopped in RPMI containing >6.3 μM apo-transferrin (Fig. 3A to C). Hence it is likely that iron sequestering by transferrin increases bacterial avidity for gallium. In support of this, the addition of 50 μM BiP to 10% TSB did not prevent overnight growth of A. baumannii but had a synergistic effect with GaN and completely inhibited growth (Fig. 3D).

Fig 3.

Enhanced gallium activity in the presence of iron-binding molecules. A. baumannii ATCC 17978 was cultured in RPMI for 16 h in the presence of gallium nitrate and chelators. Bacteria were incubated with the indicated concentrations of human (A), murine (B), and bovine (C) apo-transferrin, in the presence of RPMI diluent or 10 μM GaN. (D) Bacteria were incubated with 50 μM BiP and 10 μM GaN, alone or in combination, in 10% TSB. Results are expressed as the mean OD600 ± standard deviation for 100-μl volumes and are representative of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests.

It is not clear how transferrin, a molecule able to bind both trivalent Ga and Fe, can enhance the activity of gallium. Ga(III) and Fe(III) are normally found as insoluble salts at neutral pH. One explanation would be that unlike ferric iron, gallium can exist as a soluble anionic group: gallate, Ga(OH)4−. Gallate can reach nanomolar plasma concentrations even in the presence of unsaturated transferrin (1). Transferrin could generate an iron-deprived environment without sequestering all available gallium, making it even more hostile for bacteria. These results reveal a potential for a therapeutic use of gallium at micromolar ranges.

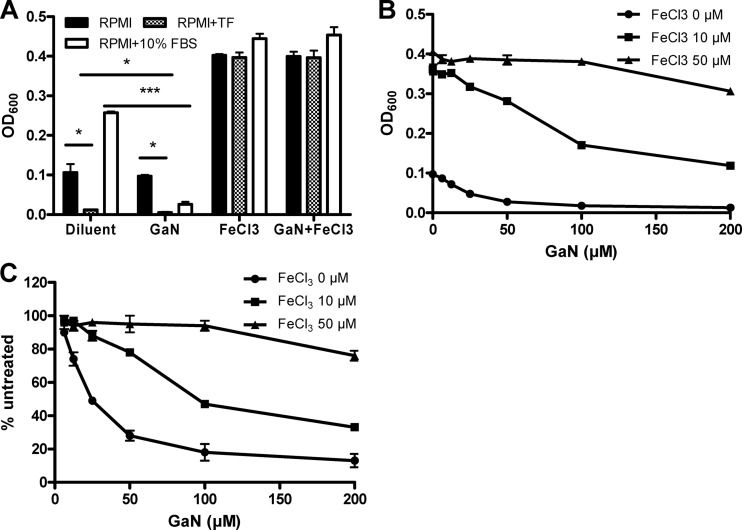

Since iron depletion and gallium treatment restrict bacterial growth, we hypothesized that excess iron would compete for and cancel out the effect of gallium. Indeed, A. baumannii displays more robust growth and is less sensitive to gallium in iron-rich TSB than iron-poor RPMI (Fig. 1). In support of our hypothesis, transferrin, serum, or gallium no longer significantly affected growth following addition of 50 μM FeCl3 to bacterial cultures in RPMI medium (Fig. 4A; P > 0.05, nonparametric Student's t test). In low-iron RPMI, FeCl3 was effective at preventing inhibition by gallium even at a ratio of 1 Fe to 4 Ga (Fig. 4B and C). These results suggest that A. baumannii will preferentially incorporate Fe(III) over Ga(III) and that conditions of high iron availability will prevent the action of gallium.

Fig 4.

Iron blocks the antimicrobial effect of gallium. A. baumannii ATCC 17978 was cultured for 5 h in RPMI with or without 10 μg/ml apo-transferrin or 10% fetal bovine serum. Gallium nitrate (10 μM) and/or ferric chloride (50 μM) was also added in the appropriate groups, and the OD600 was measured (A). Significant differences between respective samples were determined by nonparametric unpaired Student's t test: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. A. baumannii cultures in RPMI medium were grown under various concentrations of gallium nitrate (GaN) in the presence of different amounts of FeCl3 as indicated. Results are expressed as OD600 (B) or percentage of untreated samples (C) ± standard deviation and are representative of three independent experiments.

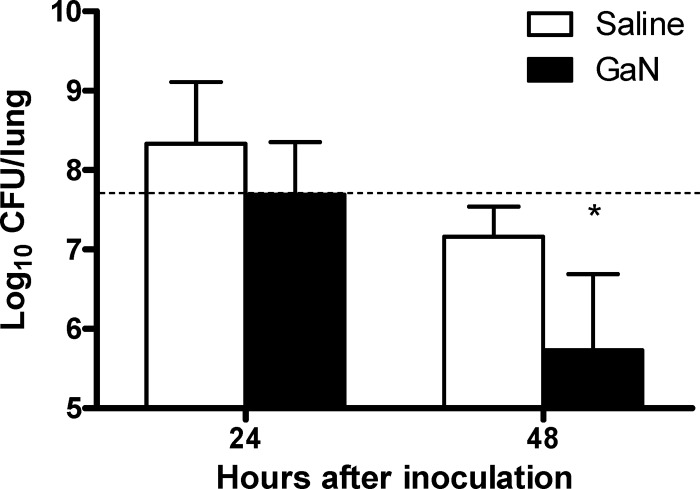

We next determined the effect of GaN on bacterial growth in the mouse model of intranasal A. baumannii infection (13, 14). The animals were maintained and used in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals, and the experimental procedures were approved by the institutional animal care committee. Neutropenic mice were treated with 25 mg/kg GaN intraperitoneally, 18 h before and 24 h after intranasal inoculation of 5 × 107 CFU A. baumannii. Immunosuppression delays the clearance of A. baumannii and facilitates the detection of bacterial growth (10, 14). Bacterial burdens in the lungs were enumerated at 24 and 48 h after infection (Fig. 5). Compared to the initial inoculum, a modest increase in bacterial counts was observed in placebo-treated mice at 24 h while no growth was observed in GaN-treated animals. At 48 h, bacterial burdens were reduced 100-fold in GaN-treated mice compared to placebo-treated mice (P < 0.05). Hence, gallium treatment appears to both prevent growth and accelerate the clearance of A. baumannii in the lung. These findings are consistent with a report showing inhibition of A. baumannii in a mouse burn model by local gallium maltolate treatment (5). Therapeutically, gallium nitrate shows low toxicity and already exists as a treatment for cancer-related hypercalcemia. However, it must be given internally in a dilute form (4). Novel formulations such as gallium maltolate exhibit high oral bioavailability and are well tolerated (2). Taken together, our results suggest that targeting iron metabolism with gallium may reveal novel therapies in an effort to treat infections by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

Fig 5.

Gallium nitrate prevents bacterial growth and accelerates clearance from the lungs of A. baumannii-infected mice. C57BL/6 mice were rendered neutropenic by injecting 25 μg of anti-Gr1 monoclonal antibodies (RB6-8C5). Groups of five neutropenic C57BL/6 mice were treated with 25 mg/kg GaN or saline intraperitoneally 18 h before and 24 h after intranasal inoculation with 5 × 107 CFU of A. baumannii ATCC 17978. The mice were sacrificed at 24 and 48 h after infection, and the lungs were aseptically removed, homogenized, and used for the determination of viable bacterial counts. Results are presented as log10 CFU per lung ± standard deviation. The dashed horizontal line represents the inoculum size. *, P < 0.05 versus saline-treated group by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests. Results are from one independent experiment of three, all with similar observations.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bernstein LR. 1998. Mechanisms of therapeutic activity for gallium. Pharmacol. Rev. 50:665–682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernstein LR, Tanner T, Godfrey C, Noll B. 2000. Chemistry and pharmacokinetics of gallium maltolate, a compound with high oral gallium bioavailability. Met. Based Drugs 7:33–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boelaert JR, et al. 1993. Mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy is a siderophore-mediated infection. In vitro and in vivo animal studies. J. Clin. Invest. 91:1979–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chitambar CR. Medical applications and toxicities of gallium compounds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7:2337–2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeLeon K, et al. 2009. Gallium maltolate treatment eradicates Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in thermally injured mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1331–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernandes SS, et al. 2010. Identification of a new hexadentate iron chelator capable of restricting the intramacrophagic growth of Mycobacterium avium. Microbes Infect. 12:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibrahim AS, et al. 2007. The iron chelator deferasirox protects mice from mucormycosis through iron starvation. J. Clin. Invest. 117:2649–2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ibrahim AS, et al. 2011. Combination therapy of murine mucormycosis or aspergillosis with iron chelation, polyenes, and echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1768–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson EE, Wessling-Resnick M. 2012. Iron metabolism and the innate immune response to infection. Microbes Infect. 14:207–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joly-Guillou ML, Wolff M, Pocidalo JJ, Walker F, Carbon C. 1997. Use of a new mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia to evaluate the postantibiotic effect of imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kontoghiorghes GJ. 2006. Iron mobilization from transferrin and non-transferrin-bound-iron by deferiprone. Implications in the treatment of thalassemia, anemia of chronic disease, cancer and other conditions. Hemoglobin 30:183–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li S, Crooks PA, Wei X, de Leon J. 2004. Toxicity of dipyridyl compounds and related compounds. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 34:447–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Renckens R, et al. 2006. The acute-phase response and serum amyloid A inhibit the inflammatory response to Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 193:187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Faassen H, et al. 2007. Neutrophils play an important role in host resistance to respiratory infection with Acinetobacter baumannii in mice. Infect. Immun. 75:5597–5608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]