Abstract

This study investigated the prevalence and cell density of Candida species in periodontal pockets, healthy subgingival sites, and oral rinse samples of patients with untreated periodontitis. Twenty-one periodontitis patients underwent sampling at two periodontitis sites, and 19/21 of these patients underwent sampling at one periodontally healthy site. Both paper point and curette sampling techniques were employed. The periodontitis patients and 50 healthy subjects were also sampled by oral rinse. Candida isolates were recovered on CHROMagar Candida medium, and representative isolates were identified. Candida spp. were recovered from 10/21 (46.7%) periodontitis patients and from 16/50 (32%) healthy subjects. C. albicans predominated in both groups and was recovered from all Candida-positive subjects. Candida-positive periodontitis patients yielded Candida from periodontal pockets with average densities of 3,528 and 3,910 CFU/sample from curette and paper point samples, respectively, and 1,536 CFU/ml from oral rinse samples. The majority (18/19) of the healthy sites sampled from periodontitis patients were Candida negative. The 16 Candida-positive healthy subjects yielded an average of 279 CFU/ml from oral rinse samples. C. albicans isolates were investigated by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) to determine if specific clonal groups were associated with periodontitis. MLST analysis of 31 C. albicans isolates from periodontitis patients yielded 19 sequence types (STs), 13 of which were novel. Eleven STs belonged to MLST clade 1. In contrast, 16 C. albicans isolates from separate healthy subjects belonged to 16 STs, with 4 isolates belonging to clade 1. The distributions of STs between both groups were significantly different (P = 0.04) and indicated an enrichment of C. albicans isolates in periodontal pockets, which warrants a larger study.

INTRODUCTION

The periodontium is composed of the gingivae, periodontal ligament, root cementum, and alveolar bone. In normal healthy gingivae, the free gingival margin and the tooth surface are in close proximity to each other, leaving very little space for microbial colonization (13). Periodontitis is an infection of the oral gingival tissue that is caused by a combination of microorganisms commonly found in dental plaque, such as streptococci, staphylococci, fusobacteria, Porphyromonas species, Campylobacter species, actinobacteria, and many others (30, 37). As periodontitis manifests, the gingival margin becomes enlarged, causing the gingival tissue to detach from the tooth, resulting in the formation of periodontal pockets. This coincides with the spread of infection and an associated inflammatory response leading to the irreversible destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. As the disease progresses, the depth of these periodontal pockets (probing pocket depth) increases, and bleeding and/or suppuration upon the probing of periodontal tissues also occurs (11). The buildup of dental plaque, the development of dental caries, or denture wearing is a risk factor for the development of periodontitis, as are particular systemic conditions that affect host immune or inflammatory responses (15, 28, 36). The treatment of periodontitis consists of the mechanical cleaning of teeth and the debridement of the associated diseased tissue, followed by improved dental hygiene.

Candida species are commensal yeasts and opportunistic pathogens that reside on mucosal surfaces and can cause oropharyngeal infection albeit usually in immunodeficient individuals, those with severe underlying diseases, and upper denture wearers. In healthy oral carriers, Candida spp. typically reside on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate and in the saliva. Candida species have been isolated from 40 to 60% of healthy mouths (29), although they are rarely found in subgingival sites in patients with good oral health (35). Candida species have frequently been isolated from periodontal pockets; however, their role, if any, in the etiology of periodontitis remains to be elucidated (5, 8, 27, 30, 35, 37). Several previous studies investigated the prevalence and possible role of Candida species in periodontitis, all of which identified C. albicans as the Candida species most frequently isolated from periodontal pockets (3, 9, 19, 20, 31, 35). Several of those studies also detected the presence of other Candida species, including Candida glabrata, Candida dubliniensis, Candida tropicalis, Candida guilliermondii, and Candida parapsilosis, in the periodontal pockets of patients with periodontitis; however, it should be noted that two of those studies involved patients who also had insulin-dependent diabetes, who are prone to Candida colonization and infection (19, 31, 38). Urzúa et al. (35) reported previously that patients with chronic periodontitis had a significantly higher level of colonization with Candida at subgingival sites than periodontally healthy individuals. However, currently, it is difficult to attribute a definitive role of Candida species in periodontitis, as studies reporting the relative abundance of Candida in periodontal pockets are mostly lacking. Furthermore, questions remain with regard to the optimal subgingival sampling technique. Previous clinical investigations comparing paper point and curette sampling methods noted significant differences between samples gained from the same site by employing these sampling techniques (7, 26). To date, there have been no investigations combining both paper point and curette sampling techniques in the investigation of the isolation of yeast species from periodontal sites.

Several previous studies investigated the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates recovered from the periodontal pockets, gingival sulci, and oral mucosae of patients with periodontitis by using molecular typing techniques such as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting, electrophoretic karyotyping, and ABC genotyping, with the latter technique being based on the presence or absence of an intron in the 25S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (1, 24, 32, 33). Pizzo et al. (24) previously used electrophoretic karyotyping to show that some C. albicans genotypes are unique to subgingival isolates, suggesting some adaptation to this environment. In contrast, Barros et al. (1) identified a genetically homogenous population of C. albicans strains in the oral cavities of patients with periodontitis by using RAPD. However, RAPD can be affected by a multitude of variables, its reproducibility is poor, and its resolving power is significantly lower than those of targeted, species-specific DNA comparison methods such as multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (34). Another study revealed that 66/128 (51.6%) subgingival C. albicans isolates recovered from a group of 11 diabetic patients with periodontitis belonged to ABC genotype B, and the remaining isolates belonged to ABC genotype A. However, it is important to note that diabetic patients are prone to oral candidiasis. Furthermore, the discriminatory power of ABC genotyping is poor, as only three types can be discriminated by using this technique (32).

In the past decade, advances in DNA sequencing technologies have enabled informative and detailed population structure analyses of Candida species to be undertaken, particularly following the establishment of species-specific MLST schemes. The application of MLST to yeast species enables the direct comparison of concatenated DNA sequence data and the resulting sequence types (STs) from distinct groups of isolates, for example, those recovered from distinct anatomical sites, geographical locations, or patient cohorts.

Previous MLST-based population biology analyses were carried out on both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. The population structure of C. albicans consists of 17 different MLST clades to which 97% of C. albicans isolates can be assigned (23). These isolates can also be distinguished by ABC genotyping, and the proportions of isolates of the A, B, and C genotypes can differ significantly between MLST clades. The population structure of C. albicans can also be analyzed by using an algorithm that is based upon related sequence types (BURST). This analysis is based on the allelic profiles defined by MLST and enables isolates to be grouped into clonal complexes (CCs) as well as predictions of putative founding genotypes. The C. dubliniensis-specific MLST technique was developed by researchers at this laboratory and has shown that the population of C. dubliniensis is composed of three closely related clades that can be distinguished further on the basis of the DNA sequence of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rDNA operon.

The main purpose of the present study was to investigate the prevalence and relative abundance of Candida species in periodontal pockets, healthy subgingival sites, and oral rinse samples of patients with untreated periodontitis. Isolates of the two most prevalent species recovered, C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, were subjected to MLST analysis. C. albicans isolates recovered from periodontitis patients were compared with oral carriage isolates recovered from oral rinse samples of healthy individuals without periodontitis. To our knowledge, this type of analysis has not been reported for isolates recovered from periodontitis patients. This study was undertaken in order to determine whether particular clonal groups were associated with periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study group.

Twenty-one patients with untreated periodontitis attending the Dublin Dental University Hospital and meeting specific inclusion criteria (see below) were included in the study (Table 1). Of these patients, 9/21 (42.9%) were male and 12/21 (57.1%) were female. During assessment, patients were provided with a patient information sheet approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Dublin, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. A detailed medical and dental history was taken for each patient, followed by an oral examination including a periodontal examination. A dentist experienced in the treatment of periodontitis carried out all clinical examinations between November 2007 and September 2009. The percentages of periodontal pockets with depths greater than 4 mm and 6 mm were recorded, as was the presence of bleeding on probing (BOP) and suppuration on probing (SOP), all performed according to standard procedures, as described previously (21). At a follow-up appointment at least 1 week after the initial appointment, informed consent was obtained from the patients, and microbial sampling for Candida species was carried out as described below. The average age of the patients with periodontitis was 42.9 years (range, 27 to 61 years). In total, 4/21 patients with periodontitis were smokers, and 3 patients wore partial dentures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with periodontitisa

| Patient | Age (yr) | Sex | Partial denture wearer | Smoker | % of periodontal pockets with BOP | % of patients with pocket depth of: |

Healthy and periodontitis site sampled in patients with periodontitis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >4 mm | >6 mm | Site | Probing depth (mm) | BOP | SOP | ||||||

| 1 | 27 | M | No | Yes | 83.3 | 55 | 27.7 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 2b | 40 | F | Yes | No | 93 | 93.5 | 91 | Periodontitis site 1 | 7 | Yes | No |

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 3 | 47 | F | No | No | 13 | 87 | 20 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 8 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 4 | 61 | M | No | No | 45.6 | 25.3 | 9.3 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 5 | 36 | M | No | No | 69.6 | 35.1 | 5.3 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 4 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 6 | 45 | F | No | No | 61 | 44 | 21.5 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 10 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 7 | 35 | M | No | No | 63 | 50 | 20 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 8 | 55 | M | No | Yes | 85.8 | 49.9 | 15.4 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 9 | 28 | F | No | No | 96.5 | 45.3 | 2.7 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 10 | 37 | F | No | No | 76.5 | 39.2 | 5.8 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 11b | 45 | M | Yes | Yes | 100 | 77.7 | 21.1 | Periodontitis site 1 | 7 | Yes | Yes |

| Periodontitis site 2 | 8 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 12 | 49 | F | No | No | 79.8 | 60.4 | 25.6 | Healthy site | 3 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 9 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 13 | 45 | M | No | No | 56.8 | 28.1 | 12.6 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 10 | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 14 | 45 | M | No | No | 10.5 | 11.5 | 33.3 | Healthy site | 3 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 15 | 56 | F | No | No | 39.8 | 15.2 | 7.2 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 10 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 16 | 36 | F | No | No | 61.3 | 8.6 | 1.3 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 4 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 17 | 31 | F | No | No | 75 | 70 | 4 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 8 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 18 | 36 | F | No | No | 68.8 | 25.8 | 3.2 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 4 | No | No | ||||||||

| 19 | 30 | M | No | No | 87.5 | 39.5 | 7.8 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 4 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 6 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 20 | 61 | F | Yes | Yes | 42.5 | 29.6 | 2.7 | Healthy site | 3 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 4 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 5 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| 21 | 56 | F | No | No | 73.1 | 60.1 | 21.2 | Healthy site | 2 | No | No |

| Periodontitis site 1 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Periodontitis site 2 | 7 | Yes | No | ||||||||

Abbreviations: BOP, presence of bleeding on probing of the periodontal pocket; SOP, presence of suppuration on probing of the periodontal pocket; M, male; F, female.

No healthy sites were available for sampling for this patient.

Fifty healthy subjects were also included in the present study. This group consisted of 21 males and 29 females, with an age range of 26 to 73 years and a mean age of 49.7 years. These healthy subjects were attending the Accident and Emergency Department of the Dublin Dental University Hospital and were sampled by oral rinse, as described below.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All patients with periodontitis included in the present study met the following inclusion criteria: they were 18 years of age or older, had at least one periodontal site demonstrating a probing depth of greater than 6 mm and BOP and two further sites demonstrating probing depths of greater than 4 mm and BOP, had a minimum of 4 teeth per quadrant, and had given informed consent. Periodontitis patients and healthy subjects were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: pregnancy or lactation, diabetes or asthma, steroid treatment during the last year, or antibiotic or antifungal treatment in the previous 2 months.

Sampling of the oral cavity, periodontal pockets, and gingival sites for Candida species.

All samplings of the oral cavity, periodontal pockets, and gingival sites were carried out at the Dublin Dental University Hospital. In order to obtain a quantitative estimate of the Candida burden in the oral cavity, patients were instructed to rinse their mouths with 10 ml of sterile distilled water provided in a 50-ml plastic sample container for 30 s and then to return the washings to the same container. Rinse samples were transported to the microbiology laboratory for processing within an hour. Upon receipt, a 1-ml aliquot was transferred into a sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf Safe-Lock microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and vortexed for 1 min, after which time a 0.1-ml sample was plated in duplicate onto CHROMagar Candida medium (CHROMagar, Paris, France) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h in a static incubator (Gallenkamp, Leicester, United Kingdom).

Subgingival sites selected for sampling included one healthy subgingival site with an absence of BOP and the two deepest periodontitis sites observed during clinical examination that displayed BOP. No healthy sites were available for sampling for two patients with periodontitis (patients 2 and 11) (Table 1). Sampling sites were isolated, and supragingival plaque was removed with cotton wool pellets. Samples were obtained by using three no. 35 sterile paper points per site (Steri-cell; Coltene Whaledent, Altstätten, Switzerland). The paper points were then immediately placed into a sterile 1.5-ml plastic tube (Sarstedt Ltd., Wexford, Republic of Ireland) containing 1 ml of yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth (10 g yeast extract per liter [Sigma-Aldrich Ltd., Dublin, Republic of Ireland], 20 g Bacto peptone per liter [Difco, Detroit, MI], and 20 g glucose per liter [pH 5.5]) and sealed. A curette sample of the subgingival plaque deposits from each site was also subsequently taken. A sterile disposable curette (Swede Dental AB, Örebro, Sweden) was inserted into each site, to the depth of the pocket in the case of periodontal sites; applied against the root surface; and moved coronally. Following sampling, the tip of the curette was removed and rotated vigorously in 1 ml of sterile YPD broth in a 1.5-ml tube in order to disperse the microorganisms (26). Subgingival paper point and curette samples were transferred to the microbiology laboratory in YPD transport medium, stored at 4°C, and processed within 24 h.

Prior to culturing, subgingival paper point and curette samples contained in YPD broth were vortexed at maximum speed by using a Heidolph vortex (Heidolph, Schwach, Germany) for 30 s and centrifuged at 2,600 × g for 3 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml YPD broth by vortexing for 30 s. Following this step, 0.1 ml was plated in duplicate onto CHROMagar Candida agar medium and incubated at 37°C for 48 h in a static incubator. The detection limit of all of these sampling procedures was 10 CFU.

Identification of Candida isolates.

Following incubation, CHROMagar Candida plates were examined, and the relative abundance of different-colored colonies was counted and recorded. Selected isolates of each colony color and morphology were purified by subculturing for further analysis. Isolates were initially presumptively identified on the basis of colony color and morphology: C. albicans isolates were distinguished from C. dubliniensis isolates on the basis of the darker blue-green appearance and smaller colony size of C. dubliniensis, in contrast to the larger, paler green colonies formed by C. albicans upon primary isolation in this medium (10). Definitive identification was undertaken by determining Candida isolate substrate assimilation profiles using the API ID 32C yeast identification system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), as described previously (13). Confirmation of the identification of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis isolates was also carried out by PCR experiments using species-specific ACT1-specific primers (4). Several single-colony isolates of each color present on primary CHROMagar Candida plates were identified for each clinical sample. Following identification, isolates were stored on plastic beads in Microbank cryogenic vials (Pro-lab Diagnostics, Cheshire, United Kingdom) at −80°C.

Routine Candida culture.

Candida isolates were routinely cultured on YPD agar or in YPD broth at 37°C. Liquid cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in an orbital incubator (Gallenkamp) with shaking at 200 rpm.

Chemicals, enzymes, and oligonucleotides.

Analytical-grade or molecular biology-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific Ltd. (Loughborough, United Kingdom). GoTaq DNA polymerase was purchased from the Promega Corporation (Madison, WI).

Nucleic acid isolation.

The extraction of DNA from Candida isolates for PCRs was performed as described previously by McManus et al. (17).

ABC genotyping of C. albicans.

Template DNAs extracted from selected C. albicans isolates were assigned to genotype A, B, or C based on the differential PCR amplification of the internal transcribed spacer region of the 25S rRNA gene, as previously described (14).

Genotyping of C. dubliniensis.

Template DNA was tested in separate PCR amplification experiments with each of the primer pairs G1F/G1R, G2F/G2R, G3F/G3R, and G4F/G4R to identify the ITS genotype of each C. dubliniensis isolate, as described previously (6).

MLST.

C. albicans isolates selected for multilocus sequence typing (MLST) were recovered from curette, paper point, and oral rinse samples and were chosen, where possible, to represent different periodontal pockets. These isolates were subjected to MLST analysis as previously described (17). Selected C. dubliniensis isolates were subjected to MLST by using an optimized scheme described previously by McManus et al. (16). All DNA sequencing reactions were undertaken commercially by Source BioScience LifeSciences (Dublin, Republic of Ireland), using an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer. Sequence analysis was performed by the examination of chromatogram files using ABI Prism Seqscape software, version 2.6 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

The identification of genotypes, allelic profiles, and STs was achieved by using the consensus C. albicans MLST website (http://calbicans.mlst.net/) or by using a local C. dubliniensis MLST database (16, 18). Clade and CC allocations were carried out by using previously identified reference STs (22) with unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) dendrograms and by using eBURST, respectively, as described previously (22). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out by using the MEGA software program, version 5 (12).

For comparative genetic analyses of oral C. albicans isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis and those recovered from healthy individuals, C. albicans isolates recovered from oral rinse samples of 50 healthy volunteers attending the Accident and Emergency Department at the Dublin Dental University Hospital were also investigated.

Statistical analyses.

Fisher's exact tests or Student t tests were carried out on data sets in the current study by using GraphPadQuickCalcs (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of patients with periodontitis.

The average percentage of periodontal sites exhibiting BOP was 65.8% ± 24.6%. In total, 45.1% ± 23.7% of periodontal pockets had a depth of >4 mm, and 17.1% ± 19.4% of periodontal pockets had a depth of >6 mm (Table 1).

Candida species and cell densities recovered from patients with periodontitis.

Candida species were recovered from 10/21 oral rinse samples and/or periodontal sites of 10/21 (47.6%) patients with periodontitis. C. albicans isolates were recovered from 10/21 (47.6%) patients with periodontitis, and C. dubliniensis isolates were recovered from 5/21 (23.8%) patients with periodontitis (Table 2). All of the C. dubliniensis isolates recovered were coisolated with C. albicans. Candida kefyr was isolated with C. albicans from one subgingival sample taken from patient 2. Candida parapsilosis was isolated from one subgingival site in patient 11 and was the only yeast species isolated from this site (Table 2); however, a C. albicans isolate was also recovered from another site in this patient by paper point. For the 10 patients from whom Candida species were isolated from an oral rinse sample, Candida species were also isolated from their subgingival sites. Interestingly, for 9 of these 10 patients from whom Candida species were recovered by oral rinse, Candida species were also recovered at higher densities from periodontal sites in each patient. In two patients (patients 2 and 11), the Candida species isolated from the subgingival niche included species not isolated from the oral rinse sample, reflecting site-specific colonization and the differing ecological niche of the subgingival site compared to that of the oropharynx in general. Interestingly, C. albicans isolates were recovered from a healthy site in patient 16 by using both curette and paper point sampling; this was the only periodontitis patient in the study from whom Candida spp. were recovered from a healthy site (Table 2). Candida sp. density counts ranged from 10 CFU/curette sample to 30,000 CFU/curette sample (average, 3,528 ± 8,743 CFU/curette sample), from 10 CFU/paper point sample to 40,000 CFU/paper point sample (average, 3,910 ± 5,466 CFU/paper point sample), and from 10 CFU/ml to 8,000 CFU/ml (average, 1,536 ± 2,384 CFU/ml) for oral rinse samples. The average Candida density counts recovered from periodontal pockets (3,719 CFU/sample) was 2.4-fold higher than the average Candida density counts recovered from oral rinse samples (1,536 CFU/ml) from the same periodontitis patients.

Table 2.

Candida species and cell densities recovered from patients with periodontitisa

| Patient |

Candida species recovered from sample type |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral rinse samples (CFU/ml) | Paper point samples (CFU/sample) |

Curette samples (CFU/sample) |

|||||

| Healthy subgingival site | Periodontitis site 1 | Periodontitis site 2 | Healthy subgingival site | Periodontitis site 1 | Periodontitis site 2 | ||

| 1 | C. albicans (80), C. dubliniensis (10) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (1,240), C. dubliniensis (170) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 2 | C. dubliniensis (8,000) | No healthy sites available | C. albicans (8,000) | C. albicans (160) | No healthy sites available | C. albicans (30,000), C. kefyr (1,200) | C. albicans (10) |

| 3 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 4 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 5 | C. albicans (310), C. dubliniensis (80) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (20,000) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (10) | C. albicans (680) |

| 6 | C. albicans (80), C. dubliniensis (110) | NCI (0) | Not tested | Not tested | NCI (0) | C. albicans (1,300) | C. albicans (1,000) |

| 7 | C. albicans (2,660) | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | NCI (0) | C. albicans (280) | C. albicans (230) |

| 8 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 9 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 10 | C. albicans (550) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (283) | C. albicans (1,090) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (1,240) | Not tested |

| 11 | C. albicans (730) | No healthy sites available | C. albicans (10) | C. parapsilosis (4,600) | No healthy sites available | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 12 | C. albicans (1,210) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (10) | C. albicans (4,520), C. dubliniensis (150) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (570), C. dubliniensis (570) |

| 13 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 14 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 15 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 16 | C. albicans (780) | C. albicans (40,000) | C. albicans (2,680) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (20,000) | C. albicans (2,970) | C. albicans (1,090) |

| 17 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 18 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 19 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 20 | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) | NCI (0) |

| 21 | C. albicans (760) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (1,900) | C. albicans (6,020) | NCI (0) | C. albicans (710) | C. albicans (490) |

NCI, no Candida spp. isolated.

Candida species and cell densities recovered from healthy volunteers.

Oral rinse sampling of 50 healthy volunteers was also carried out. This sampling was included in the present study for comparisons of oral Candida carriage rates in periodontally healthy individuals with those in periodontitis patients. Candida species were recovered from 16/50 (32%) of these patients. C. albicans was recovered from all 16 of these individuals, and 1 sample also yielded C. glabrata. Candida cell densities ranged from 20 CFU/ml to 1,080 CFU/ml (average, 279 ± 317 CFU/ml) for oral rinse samples (individual patient data not shown). Average counts from oral rinse samples of Candida-positive healthy carriers (279 CFU/ml) were 5.5-fold lower (P = 0.05, determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student t test) than average counts from oral rinse samples of periodontitis patients (1,536 CFU/ml).

MLST analysis and ABC genotyping of C. albicans isolates from periodontitis patients and healthy oral carriers.

Thirty-one C. albicans isolates recovered from periodontitis patients were subjected to MLST and yielded 19 distinct sequence types (STs). Two of the MLST alleles (SYA-178 and VPS13-242) and 13 of the STs recovered from patients with periodontitis have not been identified previously. More than one ST was identified in five of these patients; isolates belonging to at least two different STs were identified in patients 2, 5, 7, 16, and 21 (Table 3). Five isolates recovered from patient 16 using different sampling methods (paper point, oral rinse, and two curette samples) yielded four distinct STs. All five isolates recovered from patient 10 were identified as belonging to ST 444 despite being recovered from different sites and using different sampling methods (Table 3). The majority (21/31) of C. albicans isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis belonged to MLST clade 1, the most predominant MLST clade in the C. albicans population structure (22). Similarly, 26/31 of the C. albicans isolates were found to belong to C. albicans ABC genotype A, and 5 were found to belong to genotype B (Table 3). C. albicans isolates belonging to MLST clade 1 and ABC genotype A were recovered from 6/9 and 7/9 periodontitis patients, respectively.

Table 3.

MLST STs, allelic profiles, and ABC genotypes of oral C. albicans isolates recovered from periodontitis patients and healthy carriersa

| Patient | Isolate | Sample (site)b | ST | Allele type |

CC | MLST clade | ABC genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAT | ACC | ADP | PMI | SYA | VPS | ZWF | |||||||

| Periodontitis | |||||||||||||

| P1 | RM36 | PP (1) | 69 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM3 | C (2) | 2046 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 65 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM6 | PP (2) | 2046 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 65 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM8 | C (1) | 2046 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 65 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM15 | PP (1) | 2047 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 31 | 2 | 27 | 5 | S | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM9 | C (1) | 2063 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 20 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM10 | C (1) | 73 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P2 | RM14 | PP (3) | 804 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P5 | RM1 | C (1) | 2039 | 60 | 7 | 40 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 11 | A |

| P5 | RM2 | C (1) | 2040 | 60 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 114 | 15 | 12 | 11 | A |

| P5 | RM4 | PP (1) | 1751 | 60 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 11 | A |

| P5 | RM5 | PP (1) | 1751 | 60 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 11 | A |

| P5 | RM16 | ORS | 2064 | 60 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 6 | 126 | 15 | S | 11 | A |

| P7 | RM41 | C (1) | 360 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 35 | 2 | 4 | B |

| P7 | RM43 | C (2) | 2065 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 35 | 2 | 4 | B |

| P7 | RM49 | ORS | 2065 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 35 | 2 | 4 | B |

| P10 | RM28 | PP (2) | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P10 | RM34 | C (1) | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P10 | RM27 | C (1) | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P10 | RM25 | PP (2) | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P10 | RM29 | PP (2) | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P11 | RM38 | ORS | 73 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P12 | RM21 | PP (1) | 2038 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 242 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P12 | RM23 | PP (1) | 2038 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 242 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P16 | RM17 | C (1) | 2042 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P16 | RM18 | PP (1) | 2043 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P16 | RM26 | C (1) | 171 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P16 | RM19 | ORS | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P16 | RM20 | ORS | 444 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| P21 | RM11 | ORS | 2044 | 28 | 7 | 38 | 65 | 106 | 122 | 15 | 41 | 8 | B |

| P21 | RM12 | C (1) | 2045 | 28 | 7 | 38 | 2 | 106 | 122 | 15 | 41 | 8 | B |

| Healthy carriage | |||||||||||||

| HV100 | Ca100 | ORS | 1428 | 2 | 23 | 5 | 102 | 2 | 20 | 20 | S | 1 | A |

| HV102 | Ca102 | ORS | 1660 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 76 | 5 | 1 | 1 | A |

| HV107 | Ca107 | ORS | 1664 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 106 | 5 | S | 1 | A |

| HV103 | Ca103 | ORS | 1661 | 40 | 24 | 41 | 21 | 4 | 76 | 27 | S | 2 | A |

| HV106 | Ca106 | ORS | 1663 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 139 | 26 | 4 | 2 | 2 | A |

| HV109 | Ca109 | ORS | 1666 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 139 | 41 | 67 | S | 2 | A |

| HV112 | Ca112 | ORS | 1669 | 36 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 49 | 41 | 4 | S | 2 | A |

| HV105 | Ca105 | ORS | 659 | 11 | 26 | 6 | 4 | 34 | 60 | 119 | 9 | 4 | B |

| HV104 | Ca104 | ORS | 1662 | 3 | 26 | 6 | 4 | 34 | 60 | 55 | S | 4 | B |

| HV110 | Ca110 | ORS | 1667 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 56 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 4 | A |

| HV111 | Ca111 | ORS | 1668 | 14 | 14 | 30 | 4 | 56 | 3 | 8 | S | 4 | B |

| HV108 | Ca108 | ORS | 1665 | 5 | 27 | 37 | 4 | 34 | 105 | 12 | S | 11 | A |

| HV114 | Ca114 | ORS | 1671 | 4 | 19 | 6 | 4 | 61 | 15 | 201 | 58 | 15 | A |

| HV115 | Ca115 | ORS | 1672 | 4 | 60 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 41 | 4 | S | 2 | A |

| HV116 | Ca116 | ORS | 1673 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 94 | 2 | S | 1 | A |

| HV117 | Ca117 | ORS | 1674 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 34 | 62 | 8 | 47 | S | 5 | A |

Abbreviations: HV, healthy volunteer; C, curette; PP, paper point; ORS, oral rinse sample; ST, sequence type; CC, clonal complex.

Sampling methods and periodontal sites from which each isolate was recovered are indicated by the abbreviation and by the site number (in parentheses).

The 16 oral C. albicans isolates from healthy carriers were also subjected to MLST. Unique STs were identified for each of these 16 isolates: 4 isolates belonged to MLST clade 1, 5 belonged to MLST clade 2, 4 belonged to MLST clade 4, 1 belonged to MLST clade 5, 1 belonged to MLST clade 11, and l belonged to MLST clade 15 (Table 3). The majority of these isolates (13/16) belonged to ABC genotype A, and the remaining 3 isolates belonged to genotype B (Table 3).

Genetic comparison of oral C. albicans isolates recovered from periodontitis patients and from healthy individuals.

To test the genetic relatedness of the C. albicans populations recovered from the two subject groups, a neighbor-joining tree based on p-distance was constructed by using the concatenated MLST sequences. Only unique STs were included in the analysis; any duplicate STs were omitted in order to reduce bias. For several patients, the isolates recovered yielded distinct STs, which were very closely related to each other. The concatenated MLST sequences for these STs differed by the loss of heterozygosity in 3 nucleotide sites or fewer, suggesting microvariation in persisting STs in these periodontal pockets. Microvariation of persisting STs was observed for periodontitis patients 2, 5, 7, 16, and 21.

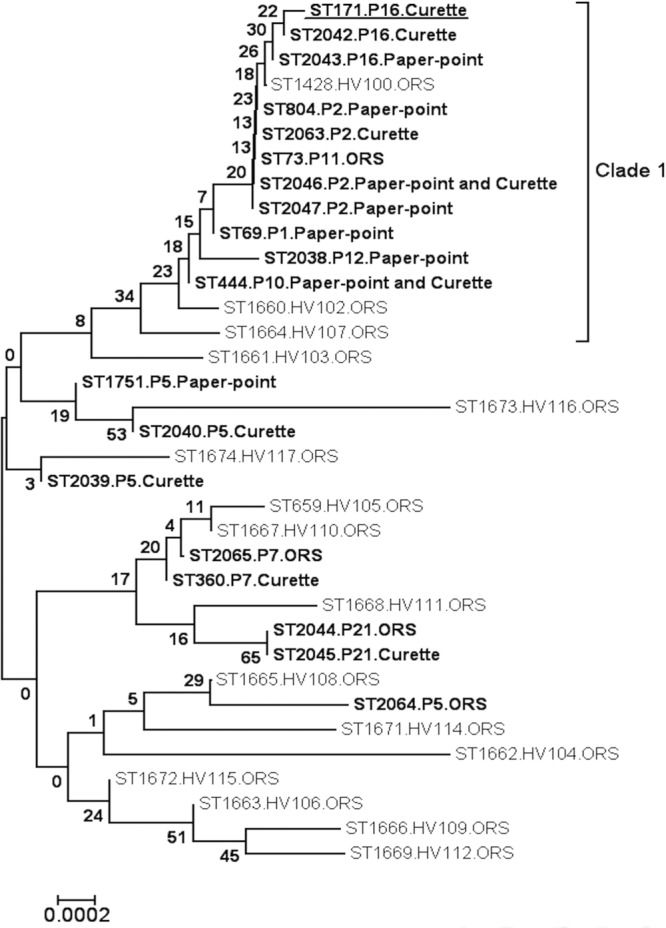

The majority of the STs identified in isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis (21/31) belonged to clade 1; these clade 1 STs were recovered from 6/9 (71.4%) patients from whom recovered C. albicans isolates were subjected to MLST. In contrast, only 4/16 (25%) of the STs identified in isolates recovered from 16 healthy Candida carriers belonged to this clade (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Surprisingly, one of the STs (ST 1673) recovered from a healthy volunteer separated from the rest of the clade 1 isolates when analyzed by neighbor-joining analysis. In order to investigate this further, a separate neighbor-joining tree containing additional clade 1 STs was constructed (data not shown). In this tree, the outlying ST clustered neatly into clade 1, so this outlier is most likely due to the limited number of STs included in the analysis.

Fig 1.

Neighbor-joining tree based on the polymorphic nucleotides in 19 of the unique STs identified in 31 C. albicans isolates recovered from 9 different patients with periodontitis and 16 unique STs identified from oral rinse samples of 16 periodontally healthy patients. Sequence types identified among isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis are indicated in boldface type, and the patients and sampling methods from which these STs were recovered are indicated alongside each ST. The ST identified for the isolate recovered from the healthy site of periodontitis patient 16 (P16) is indicated by boldface type and underlining. Sequence types identified among isolates recovered from periodontally healthy patients are indicated in normal typeface, and the patients and sampling methods from which these STs were recovered are indicated alongside each ST. The scale indicates p-distance. Eleven distinct STs recovered from 6/9 separate periodontitis patients belonged to clade 1, whereas only 4/16 STs recovered from healthy subjects belonged to this clade. Nearest-neighbor analysis of the STs in this tree indicated that the distribution of STs recovered from patients with periodontitis and those recovered from healthy individuals differed significantly (P = 0.04, determined by Fisher's two-tailed exact test). Abbreviations: OC, periodontally healthy oral Candida carrier; ORS, oral rinse sample.

Nearest-neighbor analysis of the STs in this tree indicated that the distributions of STs recovered from patients with periodontitis and those recovered from healthy individuals differed significantly (P = 0.04, determined by Fisher's two-tailed exact test), as indicated by the differing clade distributions (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

MLST analysis of C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis.

A C. dubliniensis isolate recovered from patient 1 and two C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from patient 12 were examined by using the C. dubliniensis-specific MLST scheme. One of these isolates was recovered from patient 12 by using curette sampling and was identified as belonging to ST 7, and the other isolate was recovered from this patient by oral rinse and was identified as belonging to ST 50. The third isolate examined was recovered by curette sampling of patient 1 and was also identified as belonging to ST 7. The ITS genotypes of these three isolates were also examined, and the isolates were revealed to belong to ITS genotype 1, the most commonly identified genotype (data not shown). These data showed that these isolates belonged to MLST clade C1, the most densely populated clade in the population structure of C. dubliniensis.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the prevalence, cell density, and relative abundance of Candida species in periodontal pockets, healthy gingival sites, and the oral cavity of patients with untreated periodontitis. Isolates of the most prevalent species identified, C. albicans, were subjected to MLST analysis, and the resulting data were compared with the corresponding data for C. albicans isolates recovered from healthy oral carriers of Candida without periodontitis in order to determine if there was any association of specific clonal groups with the disease. This type of in-depth population analysis has not been undertaken previously for C. albicans isolates recovered from patients with untreated periodontitis.

Although the group of patients with untreated periodontitis in the current study is relatively small (n = 21), sampling was undertaken at an average of 3 separate sites per patient and using three different sampling methods, including curettes, paper points, and oral rinse sampling. To date, there have been no investigations comparing paper point and curette sampling techniques in the investigation of the isolation of yeast species from periodontal sites. For this reason, we have used both sampling techniques in the present study. This comprehensive sampling regimen was carried out in order to obtain an accurate representation of the Candida species prevalent in the periodontal pockets of patients with periodontitis.

The chromogenic medium CHROMagar Candida was used to culture Candida species from clinical samples in order to enhance the detection of separate Candida species. Several different Candida species commonly isolated from humans exhibit characteristic colony colors on this medium, enabling the detection of mixed species in individual clinical specimens. Candida isolates were subsequently definitively identified by substrate assimilation profile analysis and by PCR. Several previous studies that reported Candida species isolated from periodontitis patients used conventional mycological media such as Sabouraud's agar for the primary isolation of Candida species (5, 27, 33). However, colonies of several Candida species can appear to be indistinguishable following primary culture on such media, resulting in a failure to detect mixed species from clinical specimens (2).

Isolates of the two most prevalent species, C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, were further characterized by ABC or ITS genotyping as well as by MLST. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine C. albicans and C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from periodontal pockets by MLST, which is now considered the gold standard for molecular typing and population analysis of Candida species. Previous studies of subgingival Candida isolates relied on less-reproducible, subjective techniques such as RAPD and electrophoretic karyotyping (1, 24, 33). The advantage of MLST is that it relies on species-specific DNA-sequence-based comparisons of isolates, and the data can be stored electronically in databases. Data from new isolates can be added gradually to the existing database and can be compared directly with data for isolates recovered from other study groups.

C. albicans was the most commonly identified Candida species in this group of patients with periodontitis, which is in agreement with data from several previous studies (1, 5, 8, 10, 32, 35). This species was most commonly recovered from 10/21 (47.6%) periodontitis patients both by oral rinse sampling and by the sampling of periodontal pockets using both paper points and curettes. Similarly, C. albicans was the species most frequently isolated from the oral rinse samples of periodontally healthy subjects, being recovered from 16/50 (32%) subjects; only 1 of these healthy patients harbored a non-C. albicans species, C. glabrata, which was coisolated with C. albicans. The average Candida density counts recovered from periodontal pockets were 2.4-fold higher than the average Candida density counts recovered from oral rinse samples from the same periodontitis patients. Furthermore, average counts from oral rinse samples from Candida-positive healthy carriers were 5.5-fold lower than average counts from oral rinse samples from periodontitis patients.

For patients 2 and 11, Candida species recovered from periodontal pockets were not recovered by oral rinse sampling of the same patient or by the sampling of an alternative periodontal pocket (Table 2), indicating site-specific colonization. Urzúa et al. previously observed that the oral mucosae of 94 to 100% of patients with periodontitis were colonized with Candida species, whereas only 44% of these patients showed Candida colonization of periodontal pockets (35). In the present study, the oral mucosae of 9/21 (42.9%) patients with periodontitis were colonized by Candida, and 10/21 (47.6%) of these patients showed Candida colonization of periodontal pockets, which demonstrates that Candida species are not a definitive cause of periodontitis. However, it is likely that Candida may exacerbate the condition, especially in periodontal pockets harboring high Candida densities. Furthermore, the results of our study showed that individual periodontal sites are specifically colonized by distinct Candida species that are not found on the oral mucosa or in other periodontal pockets, suggesting some specific enrichment of particular isolates or species at these sites. These results suggest that oral rinse sampling does not accurately reflect Candida populations present in periodontal pockets. Overall, these findings suggest Candida proliferation in at least some periodontal pockets and that the Candida counts detected were not due simply to contamination by saliva. Nineteen of the 21 periodontitis patients had healthy subgingival sites available for sampling for Candida, but only one of these sites yielded Candida isolates. The healthy site sampled from patient 16 yielded very high counts of C. albicans (20,000 CFU/curette sample and 40,000 CFU/paper point sample); however, only 780 C. albicans CFU/ml were recovered in the oral rinse sample from this patient (Table 2). The probing depth (2 mm), the lack of bleeding and suppuration upon probing at this healthy site (Table 1), and the lack of local inflammation suggested that the tooth and the site were healthy. It is difficult to explain this anomalous finding.

MLST analysis of C. albicans isolates from periodontitis patients revealed that 13/19 (68.4%) of the STs identified were previously unidentified and that the majority of these isolates belonged to clade 1, the most predominant MLST clade in the population structure of C. albicans. These STs were recovered from 6/9 (67.7%) patients for whom recovered C. albicans isolates were subject to MLST, suggesting an enrichment of this clade with isolates recovered from periodontitis patients. There did not appear to be a considerable difference in STs identified for isolates recovered from oral rinse samples and periodontal pockets, as for patient 10, separate isolates recovered by rinse, curette, and paper point methods were all identified as belonging to ST 444. Interestingly, two C. albicans isolates recovered from patient 16 were also identified as belonging to this ST (Table 3). An examination of the C. albicans MLST database (http://calbicans.mlst.net/) revealed that isolates recovered from blood, the esophagus, and the oral cavity of patients in Hong Kong, Brazil, the Netherlands, and Ireland have been identified as belonging to ST 444. The presence of this ST in more than one patient may reflect a high prevalence of this particular ST in the population at large.

Two isolates recovered from patient 21 by curette and oral rinse were identified as belonging to ST 2045 and ST 2044, respectively, but these isolates differed by only one site of heterozygosity in one allele. In contrast to the STs associated with periodontitis, only 4/16 (25%) STs of isolates recovered from the 16 separate healthy subjects belonged to MLST clade 1, whereas the rest of the isolates belonged to other clades (Table 2). Nearest-neighbor analysis and Fisher's exact testing supported the significant difference in the clade distributions between oral Candida carriers and patients with periodontitis (Fig. 1). Previous studies reported that C. albicans MLST clade 1 is enriched with isolates recovered from superficial infections as well as with ABC genotype A isolates (22). The current study shows that clade 1 is also enriched with isolates recovered from periodontitis patients. Previous to the current study, neither the C. albicans nor C. dubliniensis MLST databases contained any ST information on isolates recovered from periodontal pockets or on isolates recovered by using curettes or paper point sampling. This information has now been entered into the respective C. albicans and C. dubliniensis MLST databases for use in future analyses.

Interestingly, C. dubliniensis isolates were corecovered with C. albicans in 5/21 (23.8%) patients with periodontitis in the current study. The prevalence of C. dubliniensis in this group of 21 patients with periodontitis (23.8%) is higher than the 3.5% usually reported for the oral cavities of healthy individuals (25). Indeed, no C. dubliniensis isolates were recovered by oral rinse sampling of the 50 periodontally healthy patients included in the present study. Three of the isolates recovered from two of the patients with periodontitis were subjected to MLST, which showed that these isolates were representative of the isolates typically recovered from the human oral cavity; all three of these isolates belonged to ITS genotype 1 and MLST clade C1. This clade is the most heavily populated and least divergent clade, accounting for 66% of the 94 isolates examined by staff at this laboratory to date (16, 18).

This study is the first to investigate Candida isolates recovered from periodontitis patients by MLST, which is highly reproducible and reliable in determining the genetic relatedness between isolates of the same species. The current study used three different sampling methods to examine the Candida species and densities present in the periodontal pockets and the oral mucosa of periodontitis patients, comparing them with those present the oral mucosa of healthy subjects attending the same hospital. It is possible that the differences in Candida densities between periodontal pockets and oral rinse samples and the differential population distribution between isolates recovered from patients with periodontitis and those recovered from periodontally healthy individuals may reflect some selection of adapted isolates of Candida species to this more anaerobic environment or to other pathogens and their products present in the plaque-biofilm associated with periodontitis. It is not possible to say definitively that the presence and/or abundance of Candida in the periodontal pockets contributes to the progression of periodontitis or if it is simply a marker for the worsening of the condition. However, given the array of virulence factors, such as secreted aspartyl proteinases, that are expressed by C. albicans and the high cell densities often observed at periodontitis sites, it is likely that these organisms contribute significantly to the destruction of periodontal tissues. The novel findings of this study highlight the need for further investigations of this patient group. Such a study should examine a larger number of periodontitis patients on a longitudinal basis and should also involve the application of MLST to recovered Candida isolates, analyzing multiple isolates recovered from the each periodontal site and examining multiple periodontal sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Microbiology Research Unit, Dublin Dental University Hospital.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Barros LM, et al. 2008. Genetic diversity and exoenzyme activities of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis isolated from the oral cavity of Brazilian periodontal patients. Arch. Oral Biol. 53:1172–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coleman DC, et al. 1993. Oral Candida in HIV infection and AIDS: new perspectives/new approaches. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 19:61–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cuesta AI, Jewtuchowicz V, Brusca MI, Nastri ML, Rosa AC. 2010. Prevalence of Staphylococcus spp and Candida spp in the oral cavity and periodontal pockets of periodontal disease patients. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 23:20–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donnelly SM, Sullivan DJ, Shanley DB, Coleman DC. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis and rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis based on analysis of ACT1 intron and exon sequences. Microbiology 145(Pt 8):1871–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egan MW, et al. 2002. Prevalence of yeasts in saliva and root canals of teeth associated with apical periodontitis. Int. Endod. J. 35:321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gee SF, et al. 2002. Identification of four distinct genotypes of Candida dubliniensis and detection of microevolution in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:556–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerber J, Wenaweser D, Heitz-Mayfield L, Lang NP, Persson GR. 2006. Comparison of bacterial plaque samples from titanium implant and tooth surfaces by different methods. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 17:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jarvensivu A, Hietanen J, Rautemaa R, Sorsa T, Richardson M. 2004. Candida yeasts in chronic periodontitis tissues and subgingival microbial biofilms in vivo. Oral Dis. 10:106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jewtuchowicz VM, et al. 2007. Subgingival distribution of yeast and their antifungal susceptibility in immunocompetent subjects with and without dental devices. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 20:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jewtuchowicz VM, et al. 2008. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of Candida dubliniensis from subgingival sites in immunocompetent subjects in Argentina. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23:505–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kinnane D, Lindhe J. 2003. Chronic periodontitis, p 209–215 In Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP. (ed), Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry, 4th ed Blackwell Publishing Munksgard, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindhe J, Karring T, Araujo M. 2003. Anatomy of the periodontium, p 3–49 In Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP. (ed), Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry, 4th ed Blackwell Publishing Munksgard, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCullough MJ, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. 1999. Molecular epidemiology of the global and temporal diversity of Candida albicans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1220–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKaig RG, et al. 2000. Factors associated with periodontitis in an HIV-infected southeast USA study. Oral Dis. 6:158–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McManus BA, et al. 2008. Multilocus sequence typing reveals that the population structure of Candida dubliniensis is significantly less divergent than that of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:652–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McManus BA, et al. 2011. Microbiological screening of Irish patients with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy reveals persistence of Candida albicans strains, gradual reduction in susceptibility to azoles, and incidences of clinical signs of oral candidiasis without culture evidence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1879–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McManus BA, et al. 2009. Genetic differences between avian and human isolates of Candida dubliniensis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1467–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Melton JJ, et al. 2010. Recovery of Candida dubliniensis and other Candida species from the oral cavity of subjects with periodontitis who had well-controlled and poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Spec. Care Dentist. 30:230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miranda TT, et al. 2009. Diversity and frequency of yeasts from the dorsum of the tongue and necrotic root canals associated with primary apical periodontitis. Int. Endod. J. 42:839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nyman S, Lindhe J. 2003. Examination of patients with periodontal disease, p 403–413 In Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP. (ed), Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry, 4th ed Blackwell Publishing Munksgard, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 22. Odds FC, et al. 2007. Molecular phylogenetics of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1041–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Odds FC, Jacobsen MD. 2008. Multilocus sequence typing of pathogenic Candida species. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1075–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pizzo G, et al. 2002. Genotyping and antifungal susceptibility of human subgingival Candida albicans isolates. Arch. Oral Biol. 47:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ponton J, et al. 2000. Emerging pathogens. Med. Mycol. 38(Suppl 1):225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Renvert S, Wikstrom M, Helmersson M, Dahlen G, Claffey N. 1992. Comparative study of subgingival microbiological sampling techniques. J. Periodontol. 63:797–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reynaud AH, et al. 2001. Yeasts in periodontal pockets. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28:860–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ryder MI. 2000. Periodontal management of HIV-infected patients. Periodontology 23:85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samaranayake L. 2009. Commensal oral Candida in Asian cohorts. Int. J. Oral Sci. 1:2–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sardi JC, Almeida AM, Mendes Giannini MJ. 2011. New antimicrobial therapies used against fungi present in subgingival sites—a brief review. Arch. Oral Biol. 56:951–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sardi JC, Duque C, Camargo GA, Hofling JF, Goncalves RB. 2011. Periodontal conditions and prevalence of putative periodontopathogens and Candida spp. in insulin-dependent type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic patients with chronic periodontitis—a pilot study. Arch. Oral Biol. 56:1098–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sardi JC, Duque C, Hofling JF, Goncalves RB. 2012. Genetic and phenotypic evaluation of Candida albicans strains isolated from subgingival biofilm of diabetic patients with chronic periodontitis. Med. Mycol. 50:467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song X, Eribe ER, Sun J, Hansen BF, Olsen I. 2005. Genetic relatedness of oral yeasts within and between patients with marginal periodontitis and subjects with oral health. J. Periodontol. Res. 40:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tyler KD, Wang G, Tyler SD, Johnson WM. 1997. Factors affecting reliability and reproducibility of amplification-based DNA fingerprinting of representative bacterial pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urzúa B, et al. 2008. Yeast diversity in the oral microbiota of subjects with periodontitis: Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis colonize the periodontal pockets. Med. Mycol. 46:783–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Velegraki A, Nicolatou O, Theodoridou M, Mostrou G, Legakis NJ. 1999. Paediatric AIDS-related linear gingival erythema: a form of erythematous candidiasis? J. Oral Pathol. Med. 28:178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Waltimo TM, Sen BH, Meurman JH, Orstavik D, Haapasalo MP. 2003. Yeasts in apical periodontitis. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14:128–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Willis AM, et al. 2000. Isolation of C. dubliniensis from insulin-using diabetes mellitus patients. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 29:86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]